Labour / Le Travail

Issue 85 (2020)

Research note / Note de recherche

Trajectories of Union Renewal: Migrant Workers and the Revitalization of Union Solidarity in Saskatchewan

In 2012, two international students from Nigeria faced deportation at the hands of the Canada Border Services Agency. Their crime was to have secured work off campus, violating the terms of their student visas. Shortly after their initial detainment, both students sought sanctuary in a local church, where they avoided deportation for a year.1 Community groups, a university president, elected officials, faculty members, and activists appealed to the federal government to allow the students to stay. The Saskatchewan Government and General Employees’ Union, the largest union in the province, joined the fight. Its leadership was pressed into supporting the students’ cause by influential rank-and-file activists, with the union ultimately financing a campaign supportive of the students and their allies. It was a rare demonstration of social unionism in the province and part of what became a common story in western Canada’s resource-based economies: the re-emergence of a migrant labour force. For this reason, union renewal strategies in Saskatchewan rest heavily on the capacity of labour organizations to organize migrant and immigrant workers. This article argues that the process of community-focused renewal must commence within the existing ranks of organized workers. Such a move might involve mobilizing around issues voiced by migrant workers and their community allies during interviews, like securing affordable housing and assisting migrants with their transition to permanent residency – all of which take place in the broader political economy of Saskatchewan and Canada’s migration regime.

Facing shortages of labour, Saskatchewan employers have been pressed into looking abroad to fill vacancies in a resource-fuelled economy. As high-wage jobs in the country’s mining and oil- and gas-extractive sectors consumed workers from regional labour markets, jobs across the skill and occupational spectrum allegedly sat vacant.2 This was the dominant narrative across western Canada, where migrant workers have become a critical part of the region’s political-economic fabric.3 Starting in the early 2000s, a dramatic increase in global commodity prices launched a surge of investment into the oil, gas, and potash industries that dominated the political-economic fabric of the region.4 It was around that time that western Canadian governments, recruitment agencies, and the private sector began to eye countries such as India, the Philippines, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and even the United States as labour export markets. Enabled by a variety of migrant worker programs, employers could source workers and help tame wages by tapping into foreign labour markets. Not including the undocumented population or international students, around 595,000 migrants are now employed across Canada.5 Between 2005 and 2012, the peak of western Canada’s recent economic expansion, the number of migrants admitted through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (tfwp) climbed nearly sevenfold in Saskatchewan alone. This program constituted the principal source of migrants in the province. Around 1.3 per cent of the total workforce is constituted by migrants, and approximately 65,000 permanent immigrant workers, or 12 per cent of the labour force, call Saskatchewan home. This is higher than any period since the early 1900s.6

This article challenges prevailing assumptions about migrant workers – specifically, that they are passive and reluctant members of their respective labour organizations – by testing their attitudes toward unions, among other measures.7 Quantitative results are derived from a survey circulated among ten Saskatchewan unions representing workers across the province, which solicited 247 respondents; follow-up interviews took place in person and over the phone or Skype. A majority of research participants are drawn from occupations in health care, construction, post-secondary education, manufacturing, food services, accommodations, and security industries. The term “migrant” here is used to refer to participants who identified as falling into one of the following categories: a temporary foreign worker (tfw), in accordance with the International Mobility Program (imp) or the tfwp; refugee; permanent resident; or international student. Follow-up semistructured interviews were conducted with a representative sample of 55 union leaders, migrant advocates, and migrant workers. Based on these findings, the article argues that migrants are a foundation of union renewal in the prairie province, given their numbers and placement in the economy. An analysis of survey results suggests that migrants are strong union supporters but seek a labour organization that speaks to their unique needs and is also engaged in non-work-related issues. Wages and other “bread and butter” union concerns are important, but so too are challenges like accessing public services and affordable housing. This has transpired at a time when the Saskatchewan Party government has attempted to undermine unions by expanding management rights in the practice of labour relations, eliminating card-check certification, and attempting to suspend the rights of public-sector workers to engage in strike action through essential-services legislation.8 Nevertheless, Saskatchewan still maintains one of the highest union density rates in Canada, at 33.5 per cent, which is concentrated in important public- and private-sector industries, including health care, manufacturing, and mining.9 Renewal strategies are critical to bolster migrant labour engagement with unions in both high- and low-wage sectors. Such a strategy hinges on a community union model that is capable of bridging monetary issues with a broader examination of challenges specific to newcomers, who contribute to population growth and the province’s economic development policy objectives.

The first section of the article examines the union renewal literature, through which new methods of organizing can advance the capacity to build solidarity across the axes of status, race, gender, and class. Findings from the present survey and existing research suggest that renewal commences with an engagement strategy focused on existing members.10 This is one element of the seven-part renewal schema identified by Canadian industrial relations scholars who point to organizational restructuring, organizing the unorganized, political action, coalition building, social partnerships, transnational networking, training, and research as the pillars of union revitalization.11 Research demonstrates that the voice of organized labour has been relatively passive in a context where immigration and temporary foreign labour is increasingly defining the geography of work in Saskatchewan. Part of this passivity can be attributed to reluctance among leaders and rank-and-file members to acknowledge the differing needs and interests of particular groups of workers. The union renewal discussion is framed around the work of Jason Foster, Alison Taylor, and Candy Khan, who have developed a typology of union responses to migrant labour, specifically tfws.12 This framework influenced the survey and interview questions specific to political and community engagement so as to establish an understanding of the type of labour movement that migrants specifically aspire to be part of. The second section provides a short history of migrant-union relations in Saskatchewan, followed by a review of the province’s migrant worker regime and the lived realities facing foreign labour in the region. A subsequent section outlining the study’s methodology precedes an analysis of survey and interview findings and a discussion of the extent to which these outcomes advance the union revitalization framework.

Literature Review

This article draws upon literature related to the historical and social-scientific features of union engagement with racialized and migrant workers.13 Collectively, existing research offers a critical foundation on which the survey and theoretical formulations are based with regards to understanding the interaction between unions and their members. Key informant interviews with union representatives in Saskatchewan highlight the range of perspectives held by labour in the province. While some participants suggested that Canada’s migrant worker regime, and specifically the tfwp, is a means by which employers put downward pressure on wages, others recognize the reality of labour-market shortages in the province.14 Craft-based union representatives raised concerns over inadequate credentials, skills, and training among migrants as a point of contention. Other unions, meanwhile, see value in appealing to the first principles of unionism by organizing these workers.15 Recent Canadian studies characterize migrant workers largely as victims of exploitation – and with good cause – but rare are accounts that address union attitudes or the relationship migrants have forged within the ranks of organized labour.16 Migrant labour attitudes toward unions and their growing instrumentality within unionized industries remain largely ignored.17 The role of Canada’s migrant worker and immigration regime provides the backdrop for understanding labour’s response to these developments.

To address these concerns, Foster, Taylor, and Khan advance a rigorous analysis of union-migrant relations with their categorization of union positions on migrant workers into three types: “resistant,” “facilitative,” and “active.”18 While their focus rests on established leadership positions in healthcare, construction, and meat-packing unions, not the experiences of rank-and-file members or organizers, it nonetheless provides useful insights with which to assess union responses to the growth of a migrant labour force in western Canada. Organized labour’s various positions, in the framework of Foster, Taylor, and Khan, include unions seeing temporary foreign labour as stealing “Canadian jobs” and ignoring the intersection of migration, race, and employment (“resistant”); unions cooperating with employers in their effort to recruiting foreign labour (“facilitative”); and unions actively engaging with, and on behalf of, migrants through bargaining and education (“active”). These responses are conditioned by the industries in which the unions are situated, and the occupations they represent, as well as the broader union identities and strategies deployed by the respective labour organizations. Findings also suggest that migrants’ attitudes toward their union generally align with the union’s responses to the migrants themselves. Despite the strengths of their analysis, the conclusions drawn by Foster, Taylor, and Khan are restricted by the absence of a systemic evaluation of union attitudes across a broader cross section of industries and labour organizations. This article works to bridge that gap. Still, the authors provide a useful model that helps to make sense of the dynamic relationship unions hold with migrant workers, assisting with an understanding of what community unionism could mean in this context. While much of the literature on union renewal and revitalization focuses on the need for unions to reinvent how they engage with workers in an effort to organize new industries and workplaces, there persists a need to reflect on how these same institutions represent the interests of existing members. The “organizing model” of unionism articulates this vision, whereby unions are repurposed to empower workers to pursue their own interests through collective action. Unions, then, are “built” to foster rank-and-file activism and leadership that then forms the nucleus of a campaign.19 Internal renewal and innovation is similarly prompted by mobilization from below, in addition to when union representatives are pressured by multiple sources of influence, including civil society groups engaged in coalition-building exercises with unionized allies.20 Melanie Simms and Jane Holgate, meanwhile, point to the need for examining the political dynamics of organizing in a debate centred on what unions are mobilizing for.21 These authors resolve that such activity must “deliver sustainable increases in workplace power for unions and for workers,” suggesting that organizing practices should relate to the purpose of the organizing activity itself. Comparative studies of revitalization initiatives among European unions similarly point out that renewal efforts are indeed yielding fruit, with the caveat that unions must “manage to authentically relate to workers” and have “the capacity to effectively advance workers’ interests.”22 Even in the face of precarious employment relations, union structures that fall short of fitting into the lives of workers are capable of capturing the support and imagination of an increasingly marginalized labour force, such as young people and racialized workers.23

Case studies from the United States and the United Kingdom, meanwhile, stress the significance of recognizing the importance of non-class identities when organizing workers, along with the need for “institutions able to provide a voice for many workers previously excluded from traditional unions.”24 Multiple axes of oppression must then be considered in the same analytical spaces.25 This is arguably the most effective channel through which to articulate a definition of “community unionism” – that is, how unions view, respond to, and interact with members. As examples from the United Kingdom show, “it is not sufficient to tack organizing onto current organizational structures of the union”; instead, broader membership and community engagement “needs to be integrated into mainstream union work and allocated to the same degree of importance.”26 Efforts to cross the fault lines of race and migration in Canada require these and other forms of union renewal models, ones that transcend the transactional services that labour organizations typically deliver.27 Fundamentally, this means breaking the dichotomy between workplace and migration issues by acknowledging specific vulnerabilities and needs that migrants experience.28 One prognosis is that unions benefit by cultivating member commitment to build what Rick Fantasia describes as “cultures of solidarity” that then lead to further mobilizing capacity.29 Internal organizing among existing members falls within this paradigm. An analysis of survey data and interviews further illustrates how these frameworks might bear fruit in Saskatchewan. Reflections on the history of migrant-union relations also shed light on the importance of such dynamic approaches.

A Short History of Migrant-Union Relations in Saskatchewan

The history of Saskatchewan’s labour movement, and the political economy of work more broadly in the province, is premised on settler colonialism and migrant labour within the context of a resource-extractive economy. Some scholars have identified the treaty-making process as a “moment in the primitive accumulation of capital in Canada,” setting the stage for of westward colonial expansion.30 Immigrant and migrant labour had always been part of this project. Brokered by private capital and the state, settlement of the West throughout the 1880s unfolded through a process of colonization aimed at further exploiting natural resources by importing migrants destined for permanent settlement as a matter of public policy.31 But these efforts were nonetheless contested by a cross section of labour and business. In the early 20th century, racist sentiments driven by sections of the Anglo settler community gave rise to movements that sought to stall or end the import of immigrants from beyond the borders of the British Empire. In Saskatchewan the Regina Assembly of Native Sons of Canada, along with the Ku Klux Klan, wanted to see an end of immigration from non-preferred countries in central, eastern, and southern Europe. Labour joined this chorus. The Saskatoon Labour Trades Council advocated for immigration only “where assimilation is a certainty.”32 These sentiments were not uncommon. The southern Saskatchewan boomtown of Moose Jaw was the setting of trials in 1912 that highlighted what Constance Backhouse describes as the “explosive fusion between race, gender, and class in early twentieth-century Canada.”33 These prosecutions were based on a provincial statute that had passed only weeks earlier: the Act to Prevent the Employment of Female Labour in Certain Capacities. Organized labour had even joined with business associations to advance the law, referred to as the “White Women’s Labour Bill,” in an effort to undermine the commercial interests of Chinese proprietors.34 Indeed, this position aligned with attempts by craft unions in the province to restrict the use of foreign labour, who they believed would depress the wages of Canadian workers. These unions went further by excluding non-Europeans from their ranks, boycotting businesses employing “Asian labour,” and pressing for legislation that protected jobs for white men.35 The Trades and Labour Congress maintained this position well into the post–World War II period, favouring economically selective immigration, in contrast to the ccf-aligned Canadian Congress of Labour, which appealed for the deracialization of immigration policy.36 Historic labour battles in the province were often characterized by divisions between Anglo and eastern European “foreign” labour, exemplified by the Saskatchewan miners’ struggle of 1931 in the coal mining community of Bienfait.37 And much like the experiences in other regions, unions in the province reproduced the exclusionary and anti-immigration policies that exemplify the contradictions of Canadian labour history.38 Quieted by decades of out-migration, Saskatchewan’s labour movement is again confronted by a growing number of migrants and the unique sources of inequality and challenges they face in the labour market broadly and within the workplace specifically.39 For these reasons, Canada’s migrant labour regime merits further examination.

Saskatchewan’s Contemporary Migrant Worker Regime

Today, guest worker programs facilitate the construction of temporary migrant labour forces in what sociologist Michael Burawoy recognizes as a means of “cushioning the impact of the expansion and contraction of capital.”40 In Canada, such programs date back to the 1940s and were firmly entrenched by 1966 with the formation of the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program. The country faced a shortage of labour during World War II, and thousands of German prisoners of war toiled in the fields and prison camps that dotted Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Indigenous workers in western Canada have similarly functioned as internal migrants, particularly in the agricultural sector, as research on Alberta’s sugar-beet industry highlights. There, governments used paternalistic and coercive measures to mobilize Indigenous labour on a seasonal basis where farmers experienced perennial labour-market shortages, owing to poor pay and difficult work, in a process Ron Laliberte and Vic Satzewich describe as “Native proletarianization.”41 In all of these instances the state plays an interventionist role by facilitating the construction of a migrant labour force, be it part of a colonial project or a means of tying into the global division of labour. Across Canada’s oil-producing provinces a similar tendency emerged through the 2000s as the labour markets in those regions underwent a demographic change, made possible by decades of reforms to Canada’s now employer-led migration system.42

Table 1. Migrant worker program streams

|

Temporary Foreign Worker Program |

International Mobility Program |

Saskatchewan Immigrant Nominee Program |

|---|---|---|

|

Live-in caregivers; agricultural workers; other closed work permit holders (high skill, low skill, other) |

Agreements (nafta, other ftas); Canadian interests (reciprocal employment, intracompany transfers); other imp work permit holders |

Farm owners and operators; Saskatchewan work experience (health, hospitality, long haul truck drivers, students); international skilled workers; entrepreneurs |

An agreement between the Saskatchewan and the federal governments signed in the late 1990s secured the province more control over the immigration portfolio. With skilled labour in short supply, especially in the healthcare sector, the Saskatchewan Immigrant Nominee Program (sinp) has been used by employers to draw labour from abroad with the intention of permanent settlement.43 Migrants who enter through the program are entitled to apply for permanent residency, highlighting Saskatchewan’s aim of achieving population targets and an economic growth strategy through a business-driven nominee system. But as Table 1 outlines, the sinp is one of three principal migrant worker streams connecting the province with global labour markets. A bilateral agreement between Saskatchewan and the Philippines further cemented a linkage that facilitated the export of labour to Canada. Indeed, the discourse around migrant workers in Saskatchewan was, in recent history, focused on skill-intensive labour destined for largely unionized industries and workplaces. A period of economic expansion in the early 2000s, however, shifted this trajectory toward low-pay occupations.44 Interviews with migrants and an exploration of case studies demonstrate the unique vulnerabilities that workers throughout Canada’s migrant labour regime experience.45

Lived Realities of Migrants in Saskatchewan

Employment statistics for “immigrants” (permanent residents, landed immigrants) and “non-permanent residents” (temporary foreign workers) in Saskatchewan suggest that newcomers do not experience the same labour-market exclusion as their counterparts in other provinces. The unemployment rates of 6.6 per cent and 6.7 per cent in the two categories, respectively, rank lower than the provincial average of 7.1 per cent. Indigenous peoples, meanwhile, experience an unemployment rate of 18.6 per cent, highlighting the scope and racialized nature of labour-market exclusion in the province.46 However, challenges in accessing affordable housing, threats of deportation, fear of exercising basic employment rights, and demands by employers to violate the terms of their work permits characterize the realities facing unionized and non-unionized migrants in Saskatchewan.47 Even accessing healthcare services results in anxiety among a class of worker subject to real threats of removal from Canada should they not be able to work. As a migrant worker advocate explained during an interview, “They are afraid to go to see a doctor because whatever is going to be a diagnosis they think that is going to prevent them from [continuing to work].” Another community ally spoke of an agricultural worker “who had his appendix removed, [and] shortly after he was released from the hospital he was sent back [to his home country].” Some interviewees recounted stories of not knowing their entitlement to public health care, signalling the need for advocates and adequate settlement services. Low housing-vacancy rates provoked by a prolonged resource boom meant that low-wage migrants situated in Saskatchewan’s major urban centres and small towns struggled to secure accommodations, which added to the precarity of their situation. Stories of workers being exploited by nefarious immigration recruiters and employers also emerged.48 A new piece of legislation – the Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigrant Services Act – was crafted to help address these instances of abuse.49 Saskatchewan’s experience quickly matched what had been happening in other jurisdictions, as businesses looked to temporary migrant worker programs to fill permanent shortages of labour.50 Organized labour, meanwhile, failed to develop a coherent response and made few attempts to engage with this growing workforce, falling short of advancing “active” strategies that could align the interests of migrants and unions.51 Debates ranged between demonstrated concern over the employment conditions in which foreign labour worked, on the one hand, and a perception that tfws functioned both as union busters and low-cost alternatives to Canadians, on the other.52 Exceptions to such ambivalence, however, signal pathways for union renewal.

Responses from migrant worker activists and organizers outside of the province who reflected on the Saskatchewan experience paint an important picture of both existing limitations and best practices. Marco Luciano, co-founder of the migrant worker advocacy organization Migrante Alberta, has made this kind of bridge building a priority. Having helped to launch the Immigrant Workers Centre (iwc) in Montréal, Luciano worked to advance this model of organizing in the migrant worker hotspot of western Canada. Organizations like the iwc have been instrumental in facilitating worker organizing through a social movement paradigm and are led by migrant workers themselves.53 Fundamentally, the objective has been to normalize migrant worker issues in the ranks of organized labour. “That’s what we’ve also been trying to do in Migrante,” Luciano states during an interview. “To reach out to local unions and show that the temporary foreign program … is an issue for the working class of Canada [and that it’s important] to reach out to rank-and-file members and the working class in general.” This Alberta example provides an outline of the means through which solidarity can be built through workplace interventions and coalition building beyond the point of production, offering some instruction to Saskatchewan labour organizations as to how the community union model can enhance the voice of migrant labour.54

Methods

Quantitative and qualitative methods were deployed to construct a representative makeup of migrants across a spectrum of unionized industries and workplaces and in turn to assess their perspectives on unions and union strategies. Surveys catalogued demographic characteristics, while semistructured interviews established a pattern of lived realities confronting unionized newcomers, from employment experiences to access to housing and services, as well as their experience with unions. To reach a diverse migrant community, the survey was translated into Mandarin, Spanish, and Tagalog. Between December 2016 and June 2017 we used social media, mailouts, email listservs, and leafleting at public events to recruit participants for the online survey. Promotional material was distributed to unionized workers directly through participating union membership mailing lists, both electronic and conventional. Various other unions and community organizations helped by circulating an invitation to participate in the survey over their respective online media. A total of 247 participants completed the survey, 130 of whom were unionized. Although the response rate is hardly representative of the overall population, survey findings offer important insights about union-migrant worker relations in the province. The study represents ten labour organizations situated in the public and private sector, in health care, construction, post-secondary education, manufacturing, food services, accommodations, and security industries. The survey involved 46 branching questions focused on the following themes: citizenship status; demographics (sex, age, relationship status); number of years working in Canada; country of origin; perspectives on foreign workers; attitudes toward unions; income; educational background; industry of employment; occupation; job satisfaction; working conditions; and level of union engagement. Methods for assessing union attitudes were informed by the framework advanced by Foster, Taylor, and Khan but drawn from a modified version of Steven McShane’s measurement tool, which examines responses to unions and the labour movement in general, and premised on a seven-point Likert-type response format ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (7).55

The survey invited participants to take part in a follow-up interview; emails and phone calls were used to recruit respondents who expressed interest in the second phase of the research.56 Workplace posters were also used to promote the study, with an associated QR code made available to access the survey on mobile devices. In total, 55 individuals from various industries and workplaces in Saskatchewan agreed to participate in this dimension of the research. This method is aimed at generating broader claims about migrant experiences particular to unionized workplaces and member-union interactions rather than industry-specific perspectives. Sample-size limitations mean that a more granular analysis by sector, country of origin, and union is not possible. Semistructured interviews, which took place in person and over the phone, ranged between 15 and 60 minutes in duration. Methods advanced by contributors to the edited volume Qualitative Inquiry: Past, Present, and Future are used to analyze the interviews with a focus on establishing a dialogical relationship between researcher and participant.57 Qualitative interventions complement the quantitative methods deployed in the study in order to effectively capture the multilayered social realities that define migrant labour and migrant worker experiences specific to working conditions, migration, and union-member relations. Such an approach answers calls to expand the usage of quantitative research in sociological treatments of work and employment.58 Interview questions focused on ten principal themes: status; reasons for migration; time in Canada; experience with immigration recruiters and agencies; education and workplace experience; experience with unions and labour relations; working conditions; discrimination; perspective on foreign worker programs; and aspirations. Written responses and interview transcripts were coded using nvivo software in an attempt to systematically analyze recorded interview content specific to the central research themes. This enabled a narrative on employment conditions, union attitudes, migration, attitudes around foreign labour, and labour relations to emerge. Interviews from a corresponding study on the social determinants of health were also analyzed, specifically, elements related to working conditions and perceptions of organized labour.

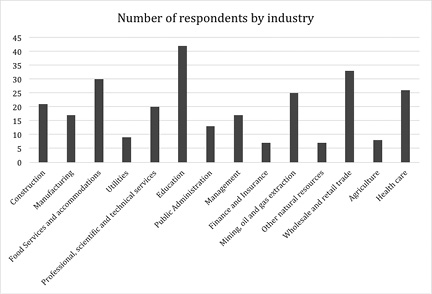

Figure 1

Migrant survey respondents come predominantly from India (24 per cent) and Nigeria (15 per cent). Filipinos constitute 11 per cent of participants. These figures accurately reflect migration trends in the province. A total of 38 foreign countries are represented in the sample. A majority of the unionized workers are employed full-time. Education is the leading industry of employment, followed by wholesale and retail, food services, and health care (Figure 1). Occupations vary across the skill and wage spectrum, providing a representative snapshot of work in the region. Most identify as men (54 per cent). This sample aligns with the distribution of migrants and immigrants across industries, according to recent census data (Table 2).59 Although the survey sample is small, it is reflective of broader provincial trends.

Table 2. Migrant workers in Saskatchewan

|

Industry |

Number of migrant workers |

Migrant workers as % of industry workforce |

Number of immigrants workers |

Immigrants as % of industry workforce |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All industries |

7,065 |

1.30% |

65,945 |

12.12% |

|

Food services & accommodations |

2,060 |

5.89% |

10,220 |

29.20% |

|

Retail |

960 |

1.60% |

8,600 |

14.32% |

|

Education |

440 |

1.00% |

3,895 |

8.86% |

|

Construction |

440 |

1.01% |

3,430 |

7.89% |

|

Health care |

410 |

0.58% |

10,735 |

15.24% |

|

Farms |

345 |

0.71% |

1955 |

4.07% |

|

Taxi & limousine |

15 |

1.38% |

590 |

54.38% |

|

Manufacturing |

295 |

1.18% |

5,260 |

14.32% |

Source: Statistics Canada, “Industry – North American Industry Classification System (naics) 2012 (425),” Catalogue No. 98-400-X2016361 (Ottawa, 2018).

Survey Findings: Toward “Active” Union Strategies

High-profile strikes led by United Food and Commercial Workers (ufcw) Local 1400, in the provincial capital of Regina, featured migrants and new Canadians in their struggle to maintain benefits and improve union rights during a bitter winter-long dispute in the food service and accommodations industry.60 The positioning of migrants in this strike aligns with broader trends within the ufcw, where efforts to advance the interests of foreign workers have resulted in best-practice collective-agreement language that helps to secure permanent residency for members.61 Saskatchewan’s taxi industry has also been a site of important union-organizing drives, spearheaded by the United Steelworkers.62 Here, migrant issues of race and precarious work have become the focus of organizing in an industry with some of the highest concentrations of foreign workers. Other examples demonstrate a tendency toward “active” models of unionism, as well. In the small oil town of Weyburn, a Steelworker local president spoke of building bridges with migrants from South Asia through social events and exchanges; these interactions translated into the recruitment of newcomers into steward positions and encouraged members to summon union support when addressing grievances. Meanwhile, skilled Filipino manufacturing workers huddled together over a fire during a strike at a farm machinery plant; down the picket line, Canadian-born co-workers criticized the use of migrant workers, during a cold winter conversation with the author, reflecting “resistive” attitudes among rank-and-file union members. So how do these examples align with case studies on migrant-union interactions in Canada?

Research findings to date highlight that Canadian union members are divided on whether or not labour organizations should do more to support foreign workers, which helps to account for why unions maintain their respective positions on migrant issues. Data from this survey, however, shows that non-Canadian unionized workers maintain support for unions, despite their recognition that these institutions have largely ignored the interests not only of migrant labour but also of the status-induced precarity that defines their existence in Canada.63 These findings also draw attention to the gap in understanding that exists when it comes to the perspectives of unions among this important and growing constituency. Responses to the statements “Unions are a positive force in Canada” and “Workers are better off when they are part of a union” were more strongly positive among Canadian than non-Canadian workers, but the data indicates that positive attitudes toward unions prevail across status (Table 3). Both constituencies hold similar, positive attitudes when it comes to the effectiveness of union representation. Interesting deviations, however, persist in where Canadian and non-Canadian workers believe unions should improve. For instance, non-Canadian workers have a stronger interest in seeing unions support workers who wish to get involved with their labour organization, improving community and political engagement, as well as extending supports to foreign and Aboriginal workers – issues that align with community unionism.64 Interviews elucidated the relationship many of these workers have, or aspire to have, with unions. All subsequent quotes with anonymous union organizers and workers are from interviews conducted by the author or members of the research team.

An assessment of participant responses suggests that voices of acclaim and criticism are dynamic, ranging from antagonistic to frustrated with a given union’s incapacity to secure meaningful gains at the bargaining table. Even those migrant workers who possess little background knowledge about organized labour expressed their understanding of a union’s capacity to support collective interests. Others demonstrated an interest in seeing the union engage more effectively with the shop floor and move beyond its traditional transactional relationship with workers. As a permanent resident employed in the meat-packing industry reflected, “I think that […] they’re not good at it cause we barely have [a wage] increase like maybe 25 cents every year. So they’re not good at it. But then if you have a problem, yeah you take it [to the union], they could help you. I’m now working in [a different local company] and it is a unionized, still a unionized company.”65 In contrast, a Canadian citizen who first arrived as a refugee, and found value in union representation, expressed apprehension about approaching his union for assistance. “You don’t feel comfortable to talk to [the union representative],” he said. “So that’s [the] part where I found the union would come in, but that’s what the union lacked because they never made themselves present.”

For skilled healthcare workers, like nurses, a different narrative is offered when it comes to engaging with arguably the most politically influential union in the province, the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses. “So … aside from [the union] representative in our [union local] you have a president [you] could go to,” explained a permanent resident who is a registered nurse. “And I think that, well, I haven’t been there, but I have communicated with the president herself through email when I have concerns or questions with anything regarding work.”

At a major warehouse distribution centre located in Regina, the pressures of an intensive labour process were raised as being among the dynamics shaping relations between migrant workers, their union (the ufcw), and the employer. A Canadian-born shop steward reflected on how a fast-paced work regime prevented even the most rudimentary forms of social solidarity to germinate on the shop floor. “If I take time to say ‘hi’ to a fellow worker, my performance goes down,” he said. “I can get fired.” A “loner mentality” permeates. In the eyes of the company, the forklift operator continued, “You are a biological machine.” Both the union and the company have coped with racial diversity in the workplace through social events, presentations, and “sensitivity” training. The union even flew in Filipino-born staffers from Toronto to help members in Regina with work visas and immigration documents, after the local recognized it needed to learn how to deal with migrant worker issues, demonstrating an affinity with “active” union tactics.

Table 3. Perception of unions

|

Union attitudes |

||

|

mean |

SD |

|

|

Unions are a positive force in Canada |

||

|

Non-Canadian (n = 51) |

2.21 |

1.242 |

|

Canadian (n = 78) |

1.94 |

1.085 |

|

Workers are better off when they are part of a union |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.19 |

1.299 |

|

Canadian |

2.01 |

1.145 |

|

If I had to choose, I probably would not be a member of a union |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

4.88 |

1.896 |

|

Canadian |

5.33 |

1.695 |

|

Workers would be better off if there were no unions in Canada |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

4.98 |

1.809 |

|

Canadian |

5.86 |

1.448 |

|

My union effectively represents the interests of its members |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.69 |

1.261 |

|

Canadian |

2.59 |

1.232 |

|

My union could do more to |

||

|

mean |

SD |

|

|

Support me and other workers in the workplace |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.13 |

1.205 |

|

Canadian |

2.71 |

1.27 |

|

Support workers who want to get involved with the union |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.25 |

1.153 |

|

Canadian |

2.6 |

1.371 |

|

Support foreign workers and assist them in becoming permanent residents |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.23 |

1.323 |

|

Canadian |

2.81 |

1.349 |

|

Improve community engagement |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.14 |

1.149 |

|

Canadian |

3.04 |

1.232 |

|

Improve political engagement |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.41 |

1.329 |

|

Canadian |

3.36 |

1.358 |

|

Support Aboriginal workers |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.29 |

1.331 |

|

Canadian |

3.37 |

1.478 |

|

Support foreign workers |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

1.94 |

1.047 |

|

Canadian |

3.64 |

1.667 |

Note: 1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree.

With the exception of the nurse in these examples, the unions failed to adopt collective-action frames through which to define interests and identities, or to recognize the causes of their problems in an attempt to solve them.66 A culture of solidarity, in the instance of the warehouse, was restricted to diversity training and antiracism initiatives and failed to catalyze a response to a labour process that both was stressful and functioned to sustain divisions between workers on the shop floor. From the “dynamics of union responses” lens, participants summoned an appeal to unions to address concerns specific to non-Canadian residents. In a static business-union model focused on bread-and-butter issues, unions have been unable to find room in the exercise of labour relations to discuss matters of status and status-induced precarity that characterize the geography of migrant labour – in other words, to find issues that would advance an “active” union strategy.67 International students in particular straddle this line, as the entanglements of enrolment and employment condition their future in Canada. Union efficacy based on this account hinges on the capacity to resolve demands that are largely alien to these students’ Canadian counterparts, speaking to the authenticity of union repertoires aimed at embracing foreign workers. An international student employed in food services explained, “I know that they [unions] will look at you as an asset at the workplace, [but] they don’t look at you in the long term. … I’m saying this ’cause so far I know the union should also help you to sort of migrate your migration status and help you to work those ways, and I haven’t had that support in that matter.”

For organizers in Saskatchewan, the conservative nature of some unions, union leaders, and even the rank-and-file helps to maintain existing divides. One staff member expressed his frustration over these structural realities, which contradict on-the-ground realities in many industries, particularly health care. This organizer’s perspective is shaped both by his ongoing interactions with workers and by a political position that espouses union renewal, one that is antiracist and rank-and-file oriented. These elements have been crucial in successful efforts at organizing largely racialized migrant labour communities.68 As one union organizer said,

One of my big dreams I guess … when I started doing internal organizing in healthcare was to get a Filipino workers committee set up where Filipino workers have their own resources and their own platform to make their own decisions and to build their own space within the union. … So when the idea of a Filipino workers committee was broached there’s leadership who say, “Well why are you, why, why are, why [are] Filipino workers getting their own committee? What about the, what about all the eastern Europeans we have. What about people from everywhere else?”

With the exception of solidarity caucuses, the migrant worker question has failed to solicit a broad-based response from the provincial labour federation or its affiliates, constituting what Foster, Taylor, and Khan identify as a “resistive” response. In these instances the union leadership is passive regarding the unique issues facing migrants, while at the same time espousing an “everyone’s equal” narrative. Equality, in this instance, has been interpreted to mean sidelining the various axes of oppression experienced uniquely by migrants. But examples in smaller locals suggest that a willingness to change persists at the leadership level, even though rank-and-file challenges remain. The president of a Steelworkers local spoke of the importance of membership mobilization and the employment realities that workers from the Philippines experience. His words demonstrated the value of “active” responses, wherein unions engage with and on behalf of migrants and recognize circumstances unique to their status and commitment to various jobs. This created tensions with fellow workers. In an interview, he said,

And now what’s happening with, with [a manufacturing company] is their efficiencies are down. You know. The work isn’t getting done. You know and what’s happening too with the workers that are working there? They’re working, their primary job … and then they’re working two or three on the side. … After your eight or ten or twelve hour shift and then working another four to five hours. … And then you’re coming to work the next day and you’re not putting out for your primary job and you’re falling asleep on the job. Uh some of them are even fighting at work, you know.

Many of these workers also request prolonged leaves of absence with the interest of visiting family back in their home countries. This, he says, “stirs the pot a bit” with both the employer and colleagues on the shop floor. What this suggests is a shortfall in the existing leave and other benefit provisions in the collective agreement, which fail to account for the global stretch of familial relations, and a broader failure to accommodate differences between many migrant workers and their Canadian-born colleagues. Realizing these “active” responses, then, demands careful negotiation between union leaders, “Canadian” workers, and employers.

Results from the survey data yield a more systematic account of these relationships, one that complements the qualitative elements of participant interviews. A clear divide exists between Canadian and non-Canadian (migrant) union members when it comes to the necessity of recruiting foreign workers in Saskatchewan, as Table 4 illustrates. Survey results also expose divides between Canadians and non-Canadians when it comes to attitudes toward migrants. Canadians are more likely to believe that migrants have the effect of lowering wages, are taking “Canadian jobs,” and are less active in their union. Interestingly, migrants are more likely to feel respected by co-workers, the union, and the general community than are their Canadian counterparts. Interviews suggest that the need for migrant workers in the province’s labour market is conditional upon the state of the economy as a whole and the industry. Canadian and migrant worker survey respondents similarly expressed suspicion over the claim that foreign workers lower wages for, and take jobs away from, Canadian workers. Both groups agreed that migrants add important diversity to their community. What this data indicates is that the perception of economic competition between Canadian and migrant workers is less severe than the public narrative implies.

When it comes to union attitudes, Canadian workers demonstrated a higher, but still comparable, rate of support (Table 3). Both constituencies typically believe that workers are better off when they are part of a union, and few would abandon union representation if given a choice. Unions are also seen as effective at representing the interests of their members. Canadians and non-Canadians shared a similar positive response when it comes to improving a union’s interaction with migrants. Non-Canadians, meanwhile, demonstrated stronger support for seeing their union improve community and political engagement than their Canadian counterparts. It is also clear that members call upon unions to improve their representation of foreign worker issues, and to pay closer attention to the specific needs of this constituency. Nearly three-quarters (74 per cent) of non-Canadian respondents believe unions should offer more support to foreign workers, such as assisting with permanent residency, compared with just 40 per cent of Canadian union members.

Survey and interview findings strengthen the appeal for a union renewal strategy that hinges upon advancing the needs and interests of migrant workers, particularly when they form a growing percentage of workers in densely unionized industries. This means addressing status and various forms of community engagement in the course of union advocacy and membership mobilization. For this to transpire, organized labour as a whole must shift from “resistive” to “active” frameworks, as the framework crafted by Foster, Taylor, and Khan suggests.69 That means deploying strategies aimed at recruiting migrants for leadership roles in the union, offering translation services where applicable, negotiating contract language that commits the union and employer to assist members in transitioning to permanent residency, accommodating diverse religious observances, and providing guidance on securing public services and housing, among other initiatives. To date, much of the work done to bridge this gap is conducted on an ad hoc basis, as union organizers and local-level leaders observe. Some unions even resist calls for the establishment of caucuses and engagement strategies that focus specifically on migrants, with leaders claiming that these strategies create factionalism and undermine the classification of members as equals. This kind of response suggests that a starting point for renewal is internal mobilization, not necessarily non-unionized workplaces.

Table 4. Foreign workers in the community and in the union

|

Perspectives on foreign workers |

||

|---|---|---|

|

mean |

SD |

|

|

Foreign workers are necessary in Saskatchewan |

||

|

Non-Canadian (n = 51) |

1.77 |

1.041 |

|

Canadian (n = 78) |

3.44 |

1.877 |

|

Foreign workers lower wages for all Canadians |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

5.02 |

1.59 |

|

Canadian |

3.79 |

1.761 |

|

Foreign workers are active in their union |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

3.62 |

1.598 |

|

Canadian |

4.29 |

1.538 |

|

Foreign workers add important diversity to my workplace |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

1.88 |

1.247 |

|

Canadian |

3.06 |

1.875 |

|

Employers should focus on employing Aboriginal workers over foreign workers |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

4.13 |

1.669 |

|

Canadian |

3.76 |

1.745 |

|

Foreign workers are taking Canadian jobs |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

5.08 |

1.713 |

|

Canadian |

3.74 |

1.819 |

|

Foreign workers add important diversity to my community |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

1.71 |

1.035 |

|

Canadian |

2.91 |

1.881 |

|

Respect at work and in the community |

||

|

mean |

SD |

|

|

I feel respected by my co-workers |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

1.88 |

1.06 |

|

Canadian |

2.31 |

1.272 |

|

I feel respected by my union and union representative |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.25 |

1.153 |

|

Canadian |

2.6 |

1.371 |

|

I feel respected by neighbours and in the general community |

||

|

Non-Canadian |

2.04 |

0.885 |

|

Canadian |

2.31 |

1.073 |

Note: 1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree.

What the findings also show is that the narrative of what constitutes community unionism merits reflection. Migrant workers possess strong attachments to their respective unions but wish to see the trajectory of bargaining represent their specific interests, such as extended periods of leave and assistance with acquiring residency for themselves and their family members. This means breaking the dichotomy between workplace and migration issues, as UK-based research signals, and requires changing the focus of transactional relations that define union service delivery as well as refining community and political engagement to match the aspirations of a diverse migrant population.70 Even the traditional repertoire of business unionism is recognized as useful, provided it is responsive to migrant-specific needs and the capacity to access union supports as they exist. A genuine labour renewal program, then, demands a more nuanced understanding of the difference between community and business unionism. For already unionized workers, this approach challenges the notion of union efficacy and summons the question of “organizing for what?” Maite Tapia’s push for establishing a culture of solidarity through the building of member commitment in unionized workplaces is of particular importance.71 Typically “resistive” unions that populate the building trades, for example, have a tradition of solidifying strong membership commitment and occupational identities. To what extent could migrants be drawn into these histories?

For unions, this also means confronting notions that migrants depress labour-market opportunities and wages, as part of the changing renewal narrative. Even the proposal of constituent-focused union caucuses summons dissent among certain elements of the union leadership, as does channelling union resources into services and bargained rights that speak to the needs of migrants. In this regard, union renewal is about not simply appealing to migrants and their workplace issues but challenging internal disputes and antagonisms between members. “Active” support for migrant workers, therefore, involves difficult conversations about commonsense perspectives on this growing constituency in western Canada.

Conclusion

Sensational accounts of workplace exploitation have dominated the narrative of migrant workers in Saskatchewan, and with good reason. Although salient, the lived realities that migrant and immigrant workers in Saskatchewan face are more complex and dynamic than these prevalent examples suggest. Furthermore, organized labour’s interjections in Saskatchewan as a whole have been largely superficial, despite significant growth in non-Canadians both as a feature of economic development and as constituent elements of the province’s population and labour-market growth strategy. Employers, meanwhile, have maintained their centrality in Canada’s business-led migrant worker and immigration regime. The story of workers who possess collective-bargaining rights and protections is largely missing from this discourse.

Interviews with workers, as well as the findings stemming from survey research, tell of a constituency that is supportive of unions yet is yearning for more rigorous engagement on issues important to migrants. Findings also illustrate that unionized migrant workers are more receptive to increased community and political engagement by the union than their Canadian brothers and sisters, and they are equally interested in becoming involved in union activities. Part of this reality is tethered to a conventional desire for individual and collective forms of voice in the workplace.72 Migrant worker allies, from organizers to union leaders, demonstrate the complexity of representing the diverse voices of this growing unionized population. They also demand a new approach to mobilization, one that draws a community unionism and union renewal framework.73 Here, the successes of workers’ action centres and immigrant workers’ centres are instructive because of their capacity, as organizations driven by the very constituency they represent, to authentically advance the interests of migrants. Models of union renewal also summon the need for engagement with these workers – a strategy that is conditional upon an understanding of the often unique realities that define a migrant worker’s existence.74 The challenge is amplified in a Saskatchewan political milieu that is increasingly anti-union and in which largely non-unionized industries are the most significant employers of migrant labour. Attitudes that question the general efficacy of unions might worsen, should this question of migrant workers remain a marginal concern among labour leaders. As a matter of pragmatism, the “resistive” forces within the ranks of labour should be replaced with “active” methods, considering the existing support among a newcomer population. Capacity to organize the unorganized – particularly in sectors with a growing proportion of migrants – demands that unions begin their engagement internally.

I owe thanks to Farha Akhtar, Nuoya (Noah) Li, and Leonzo Barreno for their contribution to the sshrc-funded project Saskatchewan in the Global Division of Migrant Labour.

1. Canadian Press, “Hundreds Rally for Nigerian Students Holed Up in Regina Church to Avoid Deportation,” Globe and Mail, 12 August 2013, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/hundreds-rally-for-nigerian-students-holed-up-regina-church-to-avoid-deportation/article13719441/.

2. Andrew Stevens, Temporary Foreign Workers in Saskatchewan’s “Booming” Economy (Regina: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2014).

3. Saskatchewan Labour Market Commission, Right People, Right Place, Right Time: Saskatchewan’s Labour Market Strategy (Regina: Government of Saskatchewan, 2009); Angela V. Carter & Anna Zalik, “Fossil Capitalism and the Rentier State: Towards a Political Ecology of Alberta’s Oil Economy,” in Laurie E. Adkin, ed., First World Petro-Politics: The Political Ecology and Governance of Alberta (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 51–77.

4. Emily Eaton & Val Zink, Fault Lines: Life and Landscape in Saskatchewan’s Oil Economy (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2016).

5. Government of Canada, “Facts & Figures 2015: Immigration Overview – Permanent Residents,” 31 July 2015, http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/2fbb56bd-eae7-4582-af7d-a197d185fc93.

6. Stevens, Temporary Foreign Workers; Statistics Canada, “Industry – North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) 2012 (425), Class of Worker (10), Admission Category and Applicant Type (8), Immigrant Status and Period of Immigration (11B), Age (5A) and Sex (3) for the Employed Labour Force Aged 15 Years and Over in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Census – 25% Sample Data,” Catalogue No. 98-400-X2016361 (Ottawa 2018).

7. Jason Foster, Alison Taylor & Candy Khan, “The Dynamics of Union Responses to Migrant Workers in Canada,” Work, Employment and Society 29, 3 (2015): 409–426.

8. Charles Smith & Andrew Stevens, “The Architecture of Modern Anti-unionism in Canada: Class Struggle and the Erosion of Workers’ Collective Freedoms,” Capital & Class 43, 3 (2018): 459–481.

9. Statistics Canada, “Union Status by Geography,” table 14-10-0129-01, accessed 2 February 2020, https://doi.org/10.25318/1410012901-eng.

10. Edmund Heery, “Sources of Change in Trade Unions,” Work, Employment and Society 19, 1 (2005): 91–106; Stephanie Ross, “Business Unionism and Social Unionism in Theory and Practice,” in Stephanie Ross & Larry Savage, eds., Rethinking the Politics of Labour in Canada (Halifax: Fernwood, 2012), 33–45.

11. Pradeep Kumar & Christopher Schenk, eds., Paths to Union Renewal: Canadian Experiences (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006).

12. Foster, Taylor & Khan, “Dynamics of Union Responses.”

13. Aziz Choudry, Jill Hanley & Eric Shragge, eds., Organize! Building from the Local for Global Justice (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2012); Suzanne Mills & Tyler McCreary, “Social Unionism, Partnership and Conflict: Union Engagement with Aboriginal Peoples in Canada,” in Ross & Savage, eds., Rethinking the Politics of Labour, 102–115.

14. Dominique Gross, “Temporary Foreign Workers in Canada: Are They Really Filling Labour Shortages?,” Commentary No. 407, C. D. Howe Institute, Toronto, 2014.

15. “usw Local 9346: Solidarity with tfws in British Columbia,” Rankandfile.ca, 17 December 2014, https://www.rankandfile.ca/deportation-and-solidarity-with-former-tfws-in-british-columbia/.

16. Fay Faraday, Profiting from the Precarious: How Recruitment Practices Exploit Migrant Workers (Toronto: Metcalf Foundation, 2014); Judy Fudge & Fiona MacPhail, “The Temporary Foreign Worker Program in Canada: Low-Skilled Workers as an Extreme Form of Flexible Labor,” Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 31, 5 (2009): 5–46.

17. Jim Warren & Kathleen Carlisle, On the Side of the People: A History of Labour in Saskatchewan (Regina: Coteau Books, 2004).

18. Foster, Taylor & Khan, “Dynamics of Union Responses.”

19. Kate Bronfenbrenner & Tom Juravich, “It Takes More Than House Calls: Organising to Win with a Comprehensive Union-Building Strategy,” in Kate Bronfenbrenner, Sheldon Friedman, Richard W. Hurd, Rudolph A. Oswald & Ronald L. Seeber, eds., Organizing to Win: New Research on Labor Strategies (Ithaca: ilr Press, 1998).

20. Heery, “Sources of Change.”

21. Melanie Simms, Dennis Eversberg, Camille Dupuy & Lena Hipp, “Organizing Young Workers under Precarious Conditions: What Hinders or Facilitates Union Success,” Work and Occupations 45, 4 (2018): 420–450; Melanie Simms & Jane Holgate, “Organising for What? Where Is the Debate on the Politics of Organizing?,” Work, Employment and Society 24, 1 (2010): 157–168.

22. Simms et al., “Organizing Young Workers,” 27.

23. Don Moran, “Aboriginal Organizing in Saskatchewan: The Experience of cupe,” Just Labour 8 (Spring 2012): 70–81.

24. Maite Tapia, Tamara L. Lee & Mikhail Filipovitch, “Supra-union and Intersectional Organizing: An Examination of Two Prominent Cases in the Low-Wage US Restaurant Industry,” Journal of Industrial Relations 59, 4 (2017): 487–509.

25. Jane Holgate, “Organizing Migrant Workers: A Case Study of Working Conditions and Unionization in a London Sandwich Factory,” Work, Employment and Society 19, 3 (2005): 463–480.

26. Holgate, “Organizing Migrant Workers,” 476.

27. Ross, “Business Unionism.”

28. Gabriella Alberti, Jane Holgate & Maite Tapia, “Organising Migrants as Workers or as Migrant Workers? Intersectionality, Trade Unions and Precarious Work,” International Journal of Human Resource Management 24, 22 (2013): 4132–4148.

29. Rick Fantasia, Cultures of Solidarity: Consciousness, Action, and Contemporary American Workers (Oakland: University of California Press, 1988); Maite Tapia, “Marching to Different Tunes: Commitment and Culture as Mobilizing Mechanisms of Trade Unions and Community Organizations,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 51, 4 (2013): 666–688.

30. Vic Satzewich & Terry Wotherspoon, First Nations: Race, Class, and Gender Relations (Toronto: Nelson Canada, 1993), 18.

31. Ron Laliberte & Vic Satzewich, “Native Migrant Labour in the Southern Alberta Sugar-Beet Industry: Coercion and Paternalism in the Recruitment of Labour,” Canadian Review of Sociology 36, 1 (1998): 72.

32. Alan B. Anderson, Settling Saskatchewan (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 5.

33. Constance Backhouse, “The White Woman’s Labor Laws: Anti-Chinese Racism in Early Twentieth-Century Canada,” Law and History Review 14, 2 (1996): 315.

34. Backhouse, “White Woman’s Labor Laws.”

35. Constance Backhouse, Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900–1950 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 138.

36. Joan Sangster, Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Post-War Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 58.

37. Stephen L. Endicott, Bienfait: The Saskatchewan Miners’ Struggle of ’31 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

38. Endicott, Bienfait; Backhouse, “White Women’s Labour Laws”; Craig Heron, The Canadian Labour Movement: A Short History, 3rd ed. (Toronto: James Lorimer, 2012); David Goutor, “Constructing the ‘Great Menace’: Canadian Labour’s Opposition to Asian Immigration, 1880–1914,” Canadian Historical Review 88, 4 (2007): 549–576.

39. For a pan-Canadian treatment of this issue, see Jason Foster, “From ‘Canadians First’ to “Workers Unite”: Evolving Union Narratives of Migrant Workers,” Industrial Relations/Relations industrielle 69, 2 (2014): 241–256.

40. Michael Burawoy, “The Functions and Reproduction of Migrant Labor: Comparative Material from Southern Africa and the United States,” American Journal of Sociology 81, 5 (1976): 1050–1087.

41. Laliberte & Satzewich, “Native Migrant Labour,” 66. Mary Jane Logan McCallum constructs a similar thesis, arguing that the state played a pivotal role in training Indigenous women to work as domestic servants and by constructing a gendered division of labour in Indigenous societies. McCallum, Indigenous Women, Work, and History: 1940–1980 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014).

42. Jason Foster & Bob Barnetson, “Who’s on Secondary? The Impact of Temporary Foreign Workers on Alberta Construction Employment Patterns,” Labour/Le Travail 80 (Fall 2017): 27–53; Sean T. Cadigan, “Boom, Bust and Bluster: Newfoundland and Labrador’s ‘Oil Boom’ and Its Impacts on Labour,” in John Peters, ed., Boom, Bust and Crisis: Labour, Corporate Power and Politics in Canada (Winnipeg: Fernwood, 2013): 68–83; Michael J. Piore, Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

43. Government of Saskatchewan, “Government Signs Immigration Agreement with the Philippines to Bring More Skilled Workers Here,” media release, 18 December 2016, http://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2006/december/18/government-signs-immigration-agreement-with-the-philippines-to-bring-more-skilled-workers-here; Salimah Valiani, Rethinking Unequal Exchange: The Global Integration of Nursing Labour Markets (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

44. Karl Flecker, “Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program: Model Program – or Mistake?,” Canadian Labour Congress, Ottawa, April 2011.

45. Stephanie Procyk, Wayne Lewchuk & John Shields, eds., Precarious Employment: Causes, Consequences and Remedies (Halifax: Fernwood, 2017).

46. Statistics Canada, “Census 2016,” custom data series.

47. Andrew Stevens, Safe Passage: Migrant Worker Rights in Saskatchewan (Regina: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2019).

48. Stevens, Safe Passage.

49. The Foreign Worker Recruitment and Immigration Services Act, ss 2013, c F-18.1.

50. Canada, Report 5, Temporary Foreign Worker Program, of the Spring 2017 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, 42nd Parl, 1st Sess (Ottawa: Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2017).

51. Andrew Stevens, “Documenting the Exploitation of Saskatchewan’s Foreign Workers,” Rankandfile.ca, 30 April 2014, http://rankandfile.ca/documenting-the-exploitation-of-saskatchewans-foreign-workers/.

52. Richard Gilbert, The Impact of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program on the Construction Labour Force in Western Canada (2003–2015): Policy Analysis and Recommendations (Surrey, BC: liuna, April 2016).

53. Aziz Choudry & Mark Thomas, “Organizing Migrant and Immigrant Workers in Canada,” in Ross & Savage, eds., Rethinking the Politics of Labour, 171–183.

54. “Migrante Alberta Is Fundraising for a Workers’ Centre,” Rank & File Radio – Prairie Edition, 7 April 2019, https://soundcloud.com/rfradio-prairie/fundraising-for-a-migrant-workers-organizing-centre-marco-luciano-migrante-alberta. Other western Canadian examples provide further guidance for Saskatchewan unions. In rural British Columbia, a Steelworkers local (usw Local 9346) representing metallurgic coal miners took up the mantle of solidarity to confront human rights abuses that migrants employed at a local coffee shop experienced. This drew the union and its leadership outside the wheelhouse of industry-specific expertise by focusing on threats of deportation and cases of exploitation facing migrants in the community. But within the ranks of Local 9346, the union president identified challenges in engaging with his own members: “They know as well as everybody else that we are against the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and I think in certain cases with some of these workers I’ve talked to a little bit on the work site, they feel like we’re against them” (interview). “usw Local 9346,” Rankandfile.ca.

55. Steven L. McShane, “General Union Attitude: A Construct Validation,” Journal of Labor Research 7, 4 (1986): 403–417.

56. Research ethics approval was secured in advance of the survey distribution, email exchanges, and interviews.

57. Norman K. Denzin & Michael D. Giardina, eds., Qualitative Inquiry: Past, Present, and Future (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2015).

58. Andy Charlwood, Chris Forde, Irena Grugulis, Kate Hardy, Ian Kirkpatrick, Robert MacKenzie & Mark Stuart, “Clear, Rigorous and Relevant: Publishing Quantitative Research Articles in Work, Employment and Society,” Work, Employment and Society 28, 2 (2014): 155–167.

59. In the Census data, “immigrant” includes permanent residents and landed immigrants. “Non-permanent residents” are persons who have been granted the legal right to live in Canada on a temporary basis, in accordance with Statistics Canada definitions.

60. Will Chabun, “Businessmen Dine as Strikers Walk Picket Line outside Regina Hotel,” Regina Leader Post, 29 January 2016, http://leaderpost.com/business/local-business/businessmen-dine-as-strikers-walk-picket-line.

61. ufcw Canada, Report on the Status of Migrant Workers in Canada – 2011 (ufcw Canada, 2011), https://www.ufcw.ca/templates/ufcwcanada/images/Report-on-The-Status-of-Migrant-Workers-in-Canada-2011.pdf.

62. Natascia Lypny, “Regina Cabs Drivers First Cabbies in Town to Unionize,” Regina Leader Post, 26 May 2016, http://leaderpost.com/news/local-news/regina-cabs-first-in-town-to-unionize.

63. Procyk, Lewchuk & Shields, Precarious Employment.

64. Suzanne E. Mills & Louise Clarke, “‘We Will Go Side-by-Side with You’: Labour Union Engagement with Aboriginal Peoples in Canada,” Geoforum 40 (2009): 991–1001.

65. In quotes from interviews, ellipses in brackets indicate pauses, hesitations, “ums,” and so on in speech.

66. Ross, “Business Unionism.”

67. Harsha Walia, “Transient Servitude: Migrant Labour in Canada and the Apartheid of Citizenship,” Race & Class 52, 1 (2010): 71–84.

68. Jennifer Jihye Chun, “Organizing across Divides: Union Challenges to Precarious Work in Vancouver’s Privatized Health Care Sector,” Progress in Development Studies 16, 2 (2016): 173–188.

69. Foster, Taylor & Khan, “Dynamics of Union Responses.”

70. Alberti, Holgate & Tapia, “Organising Migrants.”

71. Tapia, “Marching to Different Tunes.”

72. Richard B. Freeman, Peter Boxall & Peter Haynes, eds., What Workers Say: Employee Voice in the Anglo-American Workplace (Ithaca: ilr Press, 2007).

73. Jo Grady & Melanie Simms, “Trade Unions and the Challenge of Fostering Solidarities in an Era of Financialization,” Economic and Industrial Democracy 40, 3 (2018): 490–510.

74. Simms et al., “Organizing Young Workers.”

How to cite:

Andrew Stevens, “Trajectories of Union Renewal: Migrant Workers and the Revitalization of Union Solidarity in Saskatchewan,” Labour/Le Travail 85 (Spring 2020): 235–259, https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0008.

Copyright © 2020 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2020.