Labour / Le Travail

Issue 84 (2019)

presentation / présentation

Contemporary Challenges: Teaching Labour History

Introduction

As scholars and academics, we are trained and rewarded for our mastery of content, of the facts, concepts, and ideas that make up our discipline. When we start teaching, it is common for us to focus on content. We are, after all, experts. We profess our expertise to the initiates and judge them by how well they absorb what we lay before them.

This top-down process has been intensified in universities during the neoliberal period. Today, university classrooms are dominated by prerequisites, learning outcomes, scanned examinations, teaching assessments, larger classes, fewer tutorials, fixed seating, Massive Open Online Courses, and “student response systems,” that is, electronic clickers that let students “participate” by pushing a button to register a choice from displayed options. To be sure, each of these tools may have pedagogical benefits. But they are not imposed on instructors to support collaborative, democratic, sound pedagogy. Rather, they are imposed so the university administration can generate more revenue and process more units at a greatly enhanced pace. The situation is worse for the growing cadre of precarious instructors, who are often handed teaching outcomes and syllabi and assessment tools designed by someone else and whose future hiring may depend on conformity to neoliberal pedagogy. It is difficult for instructors to push back; indeed, to those raised and educated in this climate, it can be difficult even to imagine alternatives.

Yet for those who believe our work should help inform and empower those who want to engage in progressive collective action, how we teach is often more important than the content of what we teach. This means learning to teach against the trends and practices and expectations of the boss. It means thinking about teaching as a way to help people develop their own capacities for understanding and for action. It starts not with content and assessment but with the people we are teaching. It pays less attention to facts and ideas, although clearly these remain important, and more to the dynamics of the people in the class, so we may learn from each other and teach each other. It is designed to help us examine new ideas through our experiences and the experiences of others so we may become more effective. The role of the instructor is less to deliver and test for content and more to create a place where people participate and gain confidence in their own power so they push and probe one another and themselves.

Teaching in this way is not new. It is a staple of labour education where unions want to have active, militant members. It is sometimes called the “organizing model” of teaching, for it draws upon lessons from effective organizers. It starts not with the mastery of the expert but with the knowledge that people have ideas and experiences they will draw upon and that will shape how they handle new ideas. That in turn pushes the instructor to take seriously not just the content but the people in the group and to work as part of the group. It assumes that how material is delivered matters at least as much as the material itself, for the point is to help people learn how to build oppositional cultures and structures.

That is hard to do with a Scantron exam and predetermined learning outcomes. The four essays that follow share some of our experiences and experiments in teaching in a more democratic and participatory way. We are not experts, but we are long-term instructors, educators, participants, and scholars of labour history and labour studies who think about, research, collaborate, and practise teaching against the grain of neoliberalism. Our hope is that readers can adopt, adapt, reject, reshape, and build on our teaching experiences. In this way, we can share and shape our educational vision and our daily practice for a democratic, participatory future.

Teaching Labour History and Organizing Skills with Movement Activists

In addition to teaching at sfu, I teach labour history with union members, and it is often more rewarding than teaching undergraduates who take the course because it fits their timetable. Not that I am unsympathetic to their plight, but it is rewarding to work with people who care about, and will use, what we learn together. It is especially important to do this work in the contemporary period, as a new generation of activists is replacing the old layers of union leaders. The institutional, and institutionalized, history these new activists generally receive from the entrenched labour movement is too often inadequate and misleading. It is often merely a sanitized “pilgrim’s progress” history that E. P. Thompson criticized more than half a century ago.1 More often than not, this history tells workers that their greatest task as union activists is to re-elect the old incumbents and defend postwar institutions, such as the Rand Formula, that were designed to shackle the labour movement in the “golden handcuffs” of industrial legality.2

Yet these workers have a much clearer sense of the importance of labour history because they understand that knowing this history will empower them. As a result, labour history tops the list when union members are asked what courses they would like to take. But when it comes to registration, labour history is often near the bottom. That is because people feel a responsibility to take the “nuts and bolts” and “tools” courses that will immediately help their fellow workers: “Bargaining with the Boss” or “Pensions for Beginners” are more obviously practical than the perspective, context, historical explanation, and inspiration of labour history.

In my work, I try to combine labour history with practical lessons on building organizations and building solidarity. As this essay will briefly outline, one example of this is based on Vancouver’s 1912 free speech fight.

Labour History and Labour Activism

In the course I teach, I combine the history of the free speech fight with a group project, “Training for Change,” an exercise originally designed by George Lakey. Lakey was part of A Quaker Action Group, which sailed the ship Phoenix past the American 7th Fleet into Haiphong harbour in 1967, carrying medical supplies to North Vietnam. Since then he has been training organizers, including those in the civil rights movement and groups opposing mountaintop-removal coal mining. His new book, How We Win, focuses on how to build campaigns and movements and solidarity.3

This exercise, and my teaching of labour history more generally, is based first on the need to develop a “syndicalist sensibility” of militancy, radicalism, and democracy. We begin with militancy because you do not need a union if you are not going to fight to win. We then focus on radicalism, because if you are going to fight, you need to understand what you are fighting for and who is willing to fight with you. And our struggles and movements must be democratic, for, as Eugene Debs put it in 1905, “too long have the workers of the world waited for some Moses to lead them out of bondage. He has not come; he will never come. I would not lead you out if I could; for if you could be led out, you could be led back again.”4 From this syndicalist sensibility, we develop a critique of the state, capital, and much of the historical and contemporary leadership of the labour movement.

The exercise starts with a historical political emergency: the free speech fight of 1912. Street speaking was a crucial weapon for activists. When the city council of Vancouver banned unions and socialists from speaking on the street corners surrounding what is now Oppenheimer Park, it was not an act to preserve the peace. It was an attempt to stop union, socialist, and syndicalist organizers from challenging the power of the state and the employer. We know this because the city did not ban the Salvation Army from speaking and, as many noted at the time, the Army created a lot more noise and disruption with its trombones and drums than the left did with its speeches.

Yet workers continued to speak in defiance of the ban. The police then arrested speakers and threw them in jail, blocked access to the park, and continued the campaign of arrests and harassment for weeks. In addition to the story of the fight, I outline some of the history of the strands and strains in the labour and left movement – the trade unionists, socialists, the Industrial Workers of the World (iww or Wobblies). I make it clear that these groups occupied different, if overlapping, competing and conflicting positions on the economic and political planes and adopted different tactics and strategies. Whatever historical popular frontists may think, the movement before World War I was divided and fraught, and the differences were deep and profound.5

After describing the beginning of the free speech fight and the state of the movement, we move to an exercise from “Training for Change.” Its creators call it “Tornado Warning: Four Roles of Social Change” but, being from Vancouver, I tend to think more about earthquakes. The premise of the exercise is that we often assume social roles when we participate in an organization. In this context, these social roles reflect our own personalities and experiences. Sometimes these social roles create divisions when we come together to talk about tactics and strategies. To get people to think about social roles, the exercise sketches a simple scenario. I change it to fit the context, but the original reads,

The Scenario: In a Midwestern city in the US, a major tornado hits and knocks down a big manufactured home park. Almost forty people are still unaccounted for, and might be trapped in the rubble. The city’s response is terribly inadequate – both in terms of preparation for a disaster like this, and in terms of execution of its flawed plan. State and federal offices have the resources to respond, but are not adequately mobilized. The bungled relief effort highlights a number of broader issues about how the government at all levels responds, especially to working poor Midwesterners.6

I make it clear that we need to take action to get action. The question for each person is, then, How do you, as an activist, respond?

I ask people to consider their responses within one of the social roles identified in the exercise, one that feels more or less like a good fit for each person. We divide these roles into four specific categories: Helpers, Organizers, Rebels, and Advocates. The aim is to have people reflect on their own inclinations and tendencies, and the disaster – in our case, the earthquake – is more useful than a free speech role play for that purpose. There is not any order or hierarchy or preference here. In fact, all of us have all of these tendencies; different ones come out at different times and places. Here is what the roles look like, again largely taken from the “Training for Change” exercise.

Helpers jump in to give aid immediately and directly to those in need. They might help the unemployed work on résumés or fill out EI claims, or get them clothes suitable for a job interview. As children, helpers might be the ones with a Band-Aid when someone falls off their bike, or are quick to console someone who has had their feelings hurt. In an earthquake scenario, helpers head over with their first-aid kits and spare blankets. The helper is the first responder, whether in a personal crisis or a wider emergency.

Organizers love the work of bringing people together and making them into a team. They put out the union newsletter and get people out to the union meeting. As children, they might have revitalized the school pep squad, or got their class to walk out of a classroom that was led by a bullying teacher. In an emergency, they might mobilize people to form search-and-rescue teams and hold fundraising events. Organizers believe in the weight of numbers to make change and they work to get those numbers out to take action.

Rebels respond by dramatizing the problem and making voices of protest heard by the government and the public. Rebels are the children who confront the authority of teachers by demanding they justify their teaching and discipline, or who simply refuse to do as they are ordered. Rebels might fight for those made homeless by the earthquake by forming a tent city at the legislature to force the premier and the public to see, every day, what has happened to people. And if a few windows get broken and the police are called, well, that’s the price of democracy. Action, not numbers, is what matters to the rebel. No change? No peace!

Advocates communicate directly with the people in power. Civil rights lawyers sue the government to stop harassing the homeless; other advocates lobby government officials to change the policy. As children, they told their parents when a sibling was upset, or talked to a teacher about someone who was being bullied. In an emergency like an earthquake, the advocate is quick to approach and pressure the authorities to move more quickly to bring in aid. Advocates appeal to the authorities to act.

After explaining the four categories, I ask people to move to one of four corners, according to the social role they feel most drawn to – based on the earthquake scenario, not the free speech fight. Each group is asked to outline the strengths of its particular approach, to outline the weaknesses of the other approaches, and to prepare to report back to the whole group. This can take between five and fifteen minutes. The groups then report back to the whole. I am always impressed with how deeply felt the positions and reactions are. In one running of the exercise, the helpers were the only group that made sure all its members had chairs to sit in.7 Rebels castigate advocates for being co-opted; helpers lambaste rebels for getting innocent people tear-gassed at demonstrations that were supposed to be peaceful; organizers criticize helpers for not working to end the problem; advocates criticize organizers for making delicate negotiations more difficult, and so on. Because these social roles often reflect parts of our personalities and our experiences, we are quick and fierce not only to shape our choices and preferences as the best strategic and tactical responses but also to criticize the other roles. The reporting back often gets very personal, with people referring to other organizations in which they believed people in the other social roles had hurt the movement.

After the airing of grievances, I ask people to go back into their groups and list the strengths of the other groups, noting the necessary attributes they bring to the action. This time when we gather back together, we have a more rational, if sometimes grudging, discussion. Rebels, who are often criticized by all the other groups, are acknowledged as bringing much needed rebel energy and keeping the big picture clear. Helpers are respected for the immediate aid they bring. The need for organizers is made explicit, and advocates are appreciated for their potential to get immediate reform now. People have an opportunity to reflect on how personal and powerful their initial reactions were and to consider how they could get past that in a group that comes together for a common political purpose. The aim is not to undercut or blunt any of the approaches, but to see how difficult it can be to develop effective movements unless we can clarify our own roles and work with others to develop strategy and tactics.

After that discussion, we return to the Vancouver free speech fight to see how these roles were played out. Helpers made sure the arrested men got legal help and hired attorneys. In 1912, the trade unionists, with their better-paid jobs and institutions, were among the most effective helpers. Organizers held support rallies and meetings to bring together the union movement, socialists, and Wobblies to keep the pressure on and to publicize the assault on free speech, raise money for the legal costs, and win public support for the cause. Rebels took to the streets to double down on protests and arrests. They put out a call across North America for people to come to Vancouver to jump up on a soapbox and get arrested – a tactic designed to fill the jails and pressure city officials to back off. They even continued the free speech on the ocean, addressing the crowds from a rented boat. Members of the iww were most likely to be rebels; they had no vote, no connections to the authorities, but they had that rebel energy. Advocates took the fight to the provincial government, using connections with British Columbia’s members of the legislative assembly (mlas) to put pressure on Conservative premier Richard McBride to rein in the city politicians. The Socialists were effective here, as they had Socialist mlas who had access to the Conservative government.

I make it clear that the Vancouver free speech fight was not a perfect example of solidarity. Indeed, my own analysis of the fight is that the groups involved fought each other nearly as much as they fought the city and the employers. The trade unionists and the Socialist Party of Canada did not like the rebel tactic of flooding the city with hoboes. The iww noted that when the jails were filled, the city built bullpens to imprison the arrested rebels – bullpens that were built by union carpenters. But the right to organize in the streets of Vancouver was won, despite the conflicts of occupation, organization, status, and social roles. What might have been accomplished if the differences had been faced openly, with some attention paid to seeking ways to work together?

At that point, people are invited to share their experiences and comment on the exercise and what they will take back to their union. The exercise makes use of the four steps of experiential learning outlined by radical pedagogical thinkers such as Paulo Freire: (1) experience, activity, or exercise that people share; (2) reflection, where people can think and talk about what we have just done; (3) generalization, where we move from immediate thoughts and feelings to concepts and ideas that help us develop broader abstractions and think through future issues; and (4) application, where we connect the ideas to our own experience and identify lessons for the future.8

Clearly the opportunity to do more than listen to an “expert” can energize and engage people, and it can help give more lasting power to the history lesson of the free speech fight. It demonstrates some of the practical utility of labour history, and people are quick to understand that the conflict between social roles – something they have experienced directly, unlike, say, being a member of the Socialist Party of Canada – may be extended to help us think about other divisions and splits in the labour and left movements, from race and gender to job and ideology.

Typically the entire exercise takes 60 to 90 minutes. I have found it useful with participants who do not know one another well and have not worked as a group, though the most productive sessions usually involve groups who have spent time together, as participants are more generous and kindly disposed to the other social roles. That experience lets us spend more time thinking about what might be done in future emergencies.

What next? A series of Canadian historical/practical modules, developed along the lines of the American syllabus put together by William Bigelow and Norman Diamond, in The Power in Our Hands, would be a great aid to teaching labour history with both workers and university students.9 Such modules would approach labour and left history not as timelines parallel to the standard histories but as a way to make sense of the present. They would stress interaction over content and worry less about the discipline of history. They would assume that one of the best ways to learn is from experience and would build in the opportunity to reflect, generalize, and consider broader applications. The work would explicitly seek ways to build a syndicalist sensibility of militancy, radicalism, and democracy or, more accurately, to build on the elements of that sensibility that already exist among workers. It would develop new links and solidarities; it would support the building of a new labour movement that can, as Ralph Chaplin put it, “bring to earth a new world from the ashes of the old.”10

Teaching the Present to Learn the Past

Much has been written that is critical of the concept of “presentism” – the use of the present to think, write, and teach about the past. However, using the present to teach labour history is a sound pedagogical approach that allows us to engage with our students’ lived experiences. In this short essay, I explore and critically examine ways in which we can use the present to enrich our teaching, which in turn makes labour history and labour studies more relevant to our students’ lives. I argue that not only is the rejection of presentism misplaced but it takes us in the wrong direction in terms of teaching working-class history and working-class students. Moreover, presentism is not the scourge of history that its critics claim. Rather, it is actually a pedagogically sound approach to teaching labour history in the 21st century.

Thinking through “Presentism”

Lynn Hunt, past president of the American History Association, offers a clear example of the problems some historians have with the concept of presentism in an article for the aha journal in 2002. Hunt’s criticisms are not subtle, and she does not mince her words in the article’s title: “Against Presentism.”11 A more recent example of mainstream sentiment against presentism in the teaching and writing of history appeared in a 2015 article in Forbes magazine by David Davenport, entitled “Presentism: The Dangerous Virus Spreading across College Campuses.”12 It does not take much imagination to guess how these two commentators address the topic. The Davenport article is particularly critical of the re-evaluation of public statues and monuments, naming of new buildings, changing of the names of buildings, and re-evaluation of other forms of commemoration of historical figures that has been happening across the United States and Canada over the past decade. A Canadian example of this debate is recent arguments surrounding the legacy and public commemoration of John A. Macdonald.13

Hunt frames presentism as a threat to the discipline of history itself. She defines presentism as a problem that “besets us in two different ways: (1) the tendency to interpret the past in present terms; and (2) the shift of general historical interest toward the contemporary period and away from the more distant past.”14 Hunt points to the so-called dangers of presentism, laying out four foundational criticisms: First, she claims that “it threatens to put us out of business as historians.” Second, she argues that it will weaken the study of history because “if the undergraduates flock to 20th-century courses and even PhD students take degrees mostly in 20th-century topics,” other periods in history will attract less academic inquiry. Third, Hunt worries about the erosion of rigorous study, because “history risks turning into a kind of general social studies subject (as it is in K–12).” Finally, Hunt believes that if presentism is allowed to flourish, then the discipline of history “becomes the short-term history of various kinds of identity politics defined by present concerns and might therefore be better approached via sociology, political science, or ethnic studies.”15

In my opinion, the first two claims do not seem credible for labour historians, as we are not likely to be put out of business by presentism. The neoliberalization of the university over the past four decades is a far more clear and present danger to the study of working-class history and the working class itself. Many labour historians do study 20th-century topics with no ill effects. The critique of presentism turning history into a general social studies category seems to be rooted in a broader critique of K–12 education as merely content delivery. However, any good teacher will try to avoid falling into simple content delivery whether in the K–12 or the post-secondary system. In fact, using presentism can actually help avoid the pitfalls of going through history by the numbers.

The last criticism, that history as a discipline “becomes the short-term history of various kinds of identity politics defined by present concerns,” is clearly an ideological argument against the current state of critical history, which has attempted to lift the veil on the commemoration of powerful historical figures who are typically wealthy white males. Yet, the criticism masks itself in objectivity. This is the cornerstone of critiques of presentism, the idea that those who use the present to examine the past are too political or have an agenda. I would argue that no history is objective and that criticisms of one specific historical method as political are ignoring the political nature of history as a discipline.

Discussing the present to learn the past

Framing our teaching of the past within the present can help our students relate to the history we are teaching. For example, when I teach Taylorism or scientific management, I do not just ground it in a far-off historical context. Far more of my students have experience working on a hamburger assembly line in a fast-food restaurant, for instance, than on an auto factory assembly line. With apologies to my colleagues teaching in Windsor and Oshawa, most students in Canada have more work experience in service and retail jobs. Using a contemporary example of how fast-food restaurants have used Taylorism to create what Ester Reiter calls “fast food factories” allows students to relate to the topic personally, and it aids their learning.16 The critics of presentism have not taken seriously current research on the brain that demonstrates that using something familiar to teach new information helps develop the cognitive structures to retain that information. Depending on whom you are reading or talking to, this is referred to as activating prior knowledge, background schema, or, for many of us, lived experience.17 Appealing to, or invoking this experience does not represent a threat to history. Rather, this pedagogical method is a sound teaching strategy.

Structuring classes

Even for those of us who understand or perhaps intuitively know that bringing in students’ lived experience helps them engage with history, we can still feel forced into organizing our courses and lectures as a linear march through time. We do this because of the constraints of the course offering in the calendar. If it says we are covering the period from 1850, or 1867, to the present, then we try to design our lectures and the course as a whole to get us there in thirteen weeks or less. For labour history, it can look like this:

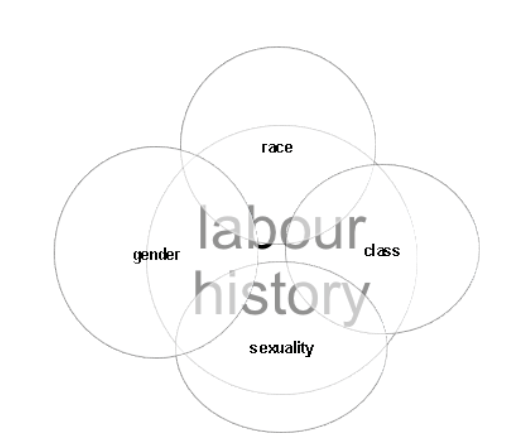

In structuring our courses this way, we end up simply marching through time. To counter this traditional structure, many of us have decided to organize our courses thematically. In doing so, our courses tend to look something like this:

However, when we try and separate out the themes, we often still end up with a linear organization – just with different themes to follow through time.

Thus, even organizing our courses thematically, we often still end up teaching in a linear way that attempts to move from a predetermined time to the present. It is not that teachers using a linear organization are unable to introduce examples from the present, or draw on students’ experiences; it is just that traditional forms of organization do not lend themselves as well to incorporating prior knowledge in the classroom as alternative forms allow.

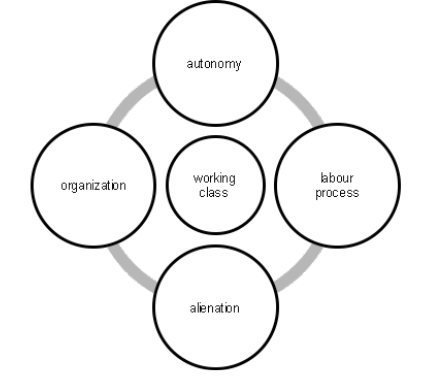

One way to avoid these pitfalls is to organize courses around the processes and logic of capitalism – the ways in which the working class and organized labour have engaged with capitalism over time. It would look something like this:

An organization in this manner would be based on ideas we want to address and enables us to discuss the labour process, the effects of capitalism on the working class, and ways the working class engages with capitalism, while focusing on processes rather than orienting the course on a linear timeline. It also allows students to think about the past in terms of structures and patterns rather than an endless listing of events. Organizing a course in terms of challenges and problems that reoccur under capitalism even when the details differ can encourage students to seek solutions to social problems that persist under capitalism.

With this approach, we could talk to our students – many of whom have experience in retail or other low-wage service work – about their histories of work. For example, we could show a training video from a store like The Gap on how to properly fold jeans as an example of a modern labour process that replicates repetitive, mind-numbing forms of older work. Many of my students have retail experience and have watched such videos, whether at The Gap, American Eagle, or any other clothing store. This can lead to a discussion of labour process, efficiency, and Fordism in a way they can relate to. Using such examples, students have a place to put this new information based on their own lived experience.

Classroom strategies

Research has shown that using present-day examples that students personally relate to allows them to integrate what they are learning into their long-term memory.18 Perhaps more importantly, if we create course assignments and in-class activities that build on these strategies and enable students to generate solutions to current problems, there is an intrinsic reward of sudden comprehension – what researchers refer to as a “reaction” to a “detection” of a schema.19 An example of this type of assignment is covered in Mark Leier’s “Tornado Warning: Four Roles of Social Change,” discussed earlier in this roundtable. Leier’s pedagogical exercise using the social role/disaster is one way of using the present to teach the past and also encourages students to generate their own conclusions about historical and contemporary problems. This type of assignment is consistent with current research, where “it has been consistently found that requiring generation, in comparison to presenting the solution, leads to enhanced later long-term memory as tested by recognition memory, cued recall, and free recall.”20 Another approach that works well in the classroom is to move beyond the traditional end-of-term final research paper. Instead, in many of my classes the final essay is reimagined as an essay on work experience, in which students take what they learned in the course and apply it to their lived experience.21

Assignments and activities do not always have to complement the students’ lived experience. They can also disrupt that experience. For example, when I teach at sfu’s Harbour Centre campus in downtown Vancouver we are a few blocks away from the Sinclair Centre, an upscale shopping mall in one of the city’s historic buildings. I take my students on a short walking tour of the area and we discuss the mall but also the history – specifically, that the building had been the Vancouver Post Office and the site of an occupation of unemployed workers during the Depression. In class, I show slides of the police eviction of the protestors, and students’ understanding of the place changes. Knowledge of the police riot disrupts their understanding of the mall as it presents itself today, by incorporating both past and present understandings of history.

There is not only one way to use the present to teach the past. Many strategies exist, including walking tours, role play, and essays integrating students’ lived experience. The point is to think through new forms of pedagogy that break out of rote memorization and encourage new ways of thinking about the past. The goal is to use the present to teach the past in order to help link ideas and social action. Most importantly, incorporating presentism into our teaching encourages our students to think critically about the past and the present.

Teaching Labour History to International Students

Since January of 2008, I have been a sessional instructor at Fraser International College, a pathway college for international students aspiring to enter Simon Fraser University.22 In that time I have taught more than 50 sections of a first-year post-Confederation survey course and 30 sections of a second-year social history of Canada course, all of them including extensive discussion of labour and working-class history. Each course has had more than 30 students, meaning I have taught events such as the 1919 workers’ revolt to more than 2,400 international students over the past decade.

Considering the depiction in the mainstream media of international students as affluent globetrotters, it might seem counterintuitive to teach them working-class history. But international students are no longer exclusively wealthy. International higher education is currently massifying – in Canada alone, international student enrolment has more than doubled since 2010, to nearly 500,000 students.23 Today’s international students are predominantly working to improve their economic futures by coming to Canada in an attempt to gain the symbolic value and the content of a Western education as a pathway to a more secure future. Perhaps even more important are their aspirations to Canadian citizenship. Between 50 and 65 per cent of international students intend to become Canadian citizens when they arrive in Canada.24 The primary path open to them is to apply to through the “Canadian Experience Class,” an immigration pathway for students who, after their studies, can secure and hold a job that the Canadian government considers “highly skilled.” For international students, the competition to find a good job defines not only their economic futures but also their access to Canadian citizenship.25

Because of this context, I have found that international students often see themselves and their own experiences in the history of workers in Canada. Therefore, teaching international students labour history has been an opportunity to build critical analysis and even solidarity in a transnational classroom. But that does not mean it is easy. Teaching international students presents several challenges beyond those already faced in the contemporary post-secondary classroom. These challenges include dealing with disparate academic cultures and very different linguistic abilities. My primary argument in this short essay is that educating international students is not a burden but an opportunity to bring into clearer focus what we wish to achieve as teachers. However, to reach our educational goals we need to radically rethink our approach to teaching in an effort to challenge the exploitative elements of post-secondary education itself, as well as to better reach our increasingly diverse students.

To teach labour history to anyone, including international students, it is important to question our attachment to traditional modes of instruction. I suspect many of us want our classes to empower students to be critical thinkers who are ready to challenge the hierarchies in our society. Yet the pedagogies we have inherited from the past – such as lectures given by experts and student ability measured via term papers and final exams – were developed for institutions that were meant to reproduce the very hierarchies we now ask students to challenge. Though the content of our courses is vastly different, the structure often looks very similar. Thus, we must start by asking ourselves a basic pedagogical question: Do our classrooms replicate, or even reproduce, the social structures we are critiquing? The additional complexities of teaching international students only make this reconsideration more pressing.

I have three suggestions for how to challenge the traditional structure of the post-secondary classroom in an effort to create a more liberating educational space, which will also increase the opportunities for international students to engage and learn. Changing three elements – grading structures, insistence on a single language of instruction, and the general reliance on a top-down model of education – can be very difficult and can engender real resistance from university administration, departments, and even our colleagues. But I will argue in each case that making these changes can unlock the potential of increasingly diverse classrooms.

Grading

In his 2007 essay “Giving Up the Grade,” David Noble makes the argument that grades are “publicly-subsidized pre-employment screening” for employers and that once they are recorded on students’ transcripts they serve as “measurements of [the] prospective labour force” for industry. For international students, grades are also indirectly measures of their fitness for citizenship. Eliminating grades, Noble argues, “shifts academic attention away from evaluation to education, where it belongs.”26 I suspect that for many readers, as for me, eliminating grades is not a realistic possibility. However, his points are valid – they invite us to rethink grading structures by considering what we really want grades to measure. Answering that question can reveal what we want our students to learn and can aid in the shift from a classroom based on evaluation to one based on education.

When I started as an instructor, I relied on conventional writing assignments, and my students struggled terribly. They also hated them. Over time I came to notice a gap – when I spoke to students, they had sophisticated things to say about labour history; when they wrote their essays, those ideas disappeared. I eventually abandoned large-scale writing assignments and have since moved to a more diverse collection of assignments that explicitly ask students to reflect on ideas that I feel are the key concepts in the course. In an effort to make grading more transparent and less traumatic for students, I have also changed the structure of my grading to invite students to sign up for a grade at the start of the semester, with clear expectations about what getting that grade will entail. I then allow students to continue to revise their work until they complete all requirements for their chosen grade level. I have found that this results in excellent work and in much more engaged students. Moreover, this system is still satisfying the institutional grading requirements that I, as a precarious university employee, cannot escape.

Language

A second mainstream pedagogical assumption I want to challenge is the idea of a single language of instruction. Our attachment to a uniform language in the classroom only reinforces already-existing colonial hierarchies that shape international student mobility. At my institution, some instructors require students to sign a “language contract” promising they will speak English, and many institutions enforce zero-tolerance policies on students speaking other languages, especially in classrooms.

Unsurprisingly, students find these rules oppressive and alienating, and they often make insightful links between their status and historical parallels, such as the Chinese Head Tax or Canada’s history of colonial language policies. It is also a very unrealistic expectation, as research shows that students for whom English is not their primary language can take as long as five years to master academic language, even if they are fluent in more colloquial English.27 I think it behooves us to resist the assumption that mastery of English is in some way necessary for international students to learn the ideas we want them to think through.

With that in mind it is important to remember, when teaching a population of students for whom the language of instruction is an additional language, that the students might find not only that comprehension and writing are a challenge but also that translating their thoughts is time consuming and difficult. If you want students to grapple with your ideas, but are less concerned with how they do that, then allow them to speak, or even write, in languages other than the language of instruction. It is unlikely that instructors will be in a position to grade this work, and presumably at some point you are going to ask the students to share their thoughts in the classroom language, but by letting them think through ideas first, you reduce pressure and let them focus on thinking about what is most important.

In my classes I challenge the assumption of English supremacy by engaging in small group activities in whichever language students prefer; then, the groups are invited to share their insights in English with the rest of the class. I find that this tactic especially benefits students who are interested in the material but perceive themselves to be poor speakers of English. A key factor in determining whether students for whom the language of instruction is an alternate language are willing to communicate is confidence in their language skills and in the social situation.28 Thus, if your goal is to engage students in class discussion, objectively improving their language skills is less important than building their confidence in their ability to explain their ideas. Even simply challenging the perceived supremacy of the language of instruction – for example, by inviting a discussion of how the spread of English is linked to Anglo-American imperialism and global capitalism – can empower students to feel more confident and can give them a critical framework to help explain their experiences.

Disrupting the Banker’s Model

The final structural element I want to address here is the educational model that presumes instructors are experts who deliver knowledge to students who are imagined to be empty vessels waiting to be filled. Paulo Freire called this the “banker’s model of education,” and he insisted that “those truly committed to liberation must reject the banking concept in its entirety.”29 His point was that this banking concept – in which an instructor deposits knowledge in a student, who is expected to hold on to what is deposited – reproduces the oppressive social structures of broader society. Only by escaping this model can truly emancipatory education be achieved. Of course, this is easier said than done; in fact, one might argue that the entire structure of post-secondary education is the banker model writ large. Working within that structure to challenge it is very difficult, in my experience, but I think it is vital if we want to make social change with our teaching.

In my efforts to escape the banker’s model, my approach to teaching has changed dramatically. I have moved away from scripted lectures and rarely use PowerPoint-style presentations. These decisions grew from a desire to engage the students more directly in the material and from the realization that, with international students, lectures and PowerPoints were widening the gap between them and meaningful engagement. Instead, I write notes on the board and engage students in discussions. A lecture will be broken up into small pieces to allow opportunities for students to respond and to explore the implications of the material. We often break into small groups to explore concepts. Another tactic that has been successful is to turn reading lists into menus and to invite discussions in class about selecting the topics (and related materials) that are of interest to the group as a whole, rather than assuming I know what is most important for the students to learn.

These changes have meant I have had to radically revise the amount of content I want to cover in my courses – I likely discuss half of what I did in a single semester when I was more dedicated to a conventional structure. But the payoff, when it comes, is incredible. One recent example was a broad, hour-long conversation about the role of race in workers’ lives, sparked by John Lutz’s work examining Indigenous workers in British Columbia in the late 19th century.30 On the face of it, that topic, while important, would not appear to be of special interest to international students. But by approaching it in a dialogic way we ended up with a powerful discussion about how the labour of workers of colour was often ignored in both history and contemporary society. I do not want to make it sound like I have successfully integrated Freire’s methods – my achievements are often more modest than that discussion, and there are days when I find the emotional labour involved to be exhausting. But I view it as an ongoing process, something I am constantly learning and trying to improve at – and something that is deeply worthwhile.

Building a Container

My final suggestion is much less structural and more about a philosophy underpinning my approach to teaching international students. Perhaps the most important step to creating a dialogic classroom and empowering students to be critical and to learn and change themselves is to build what pedagogical theorist George Lakey calls a “container.” The term refers to the sense of solidarity and mutual aid that can be built within a classroom so that students trust one another and their instructor. As Lakey puts it, “to learn, people need to risk … to risk, people need safety. To be safe, they need a group and/or a teacher that supports them.”31 If you want international students to participate in class discussion and to really engage with the concepts within working-class history, you need to make the classroom a place where they feel safe. I am sure everyone is doing this kind of work in their classrooms already, but with international students we need to do much more of it than with domestic students. They experience profound barriers (as do many domestic students, of course) – barriers that are linguistic and cultural but also racialized, gendered, and classed. Building a container can help to challenge and even tear down these barriers.

Containers are not about making students comfortable – as Lakey argues, it is sometimes important to make students uncomfortable in our efforts to explore and challenge exploitation and inequality. Containers are about making students feel safe – safe enough to take the risks necessary to be truly critical. In my experience, building a container is not about just about icebreakers and games; it is about what Open Schools founder Herbert Kohl called “education built on accepting [the] hard truth of society,” that is, education that faces up to and challenges the inequalities and injustices happening in our lives.32 International students’ experiences of racialized, gendered, neocolonial mobility are different than, but connected to, the experiences of domestic students. When tapped into, these links can foster rich cross-cultural exchanges about the shared challenges of the contemporary global economy.

I have had a lot of success with little things, like applauding student groups both before and after they give class presentations and encouraging students to talk about the context for workers in their home jurisdictions. Such actions often spark impromptu comparative conversations about work life around the globe. I have also appreciated the results of some structured activities – for example, Mark Leier’s “airplane game” has been a great hit in my labour studies classes.33 Leier’s game replicates the process of deskilling of labour by creating a paper airplane assembly line while also helping to build connections among the students in the class. Ultimately, building a strong container means making a personal commitment as an instructor to constantly attend to the emotional state of our group. This requires me to trust my ability to read the room and empathize but also to be willing to take the time to do the necessary container building to prepare us to deal with difficult topics.

To build a justice-oriented education, we have to embrace a pedagogy that challenges the historic role of post-secondary education as reproductive of an exploitative and violent social order. Our approach must help us to work collaboratively to find solutions to problems that all participants share. Excitingly, our classrooms are increasingly full of people from all over the world who are enmeshed in global capitalism in different but intersecting ways. A new pedagogy could help to unlock a vibrant future of solidarity and struggle both in our classrooms and in society more generally.

Special thanks to Mark Leier, Andrea Samoil, John-Henry Harter, and the editors of Labour/Le Travail.

Scripted Celebration: Issues in Commemorating Modern Labour History

This essay uses a 2016 workshop organized by the Alberta Labour History Institute (alhi) in Edmonton as a starting point to consider how labour historians should approach public commemoration of historical events. I examine the tensions that exist between efforts to celebrate historical events and efforts to critically evaluate and learn from prior struggles. While this is a critical contemplation of the efficacy of this workshop, it is not intended as a criticism of the hard work done by the people who organized the event.

In 2016, alhi organized a series of events to commemorate the strike wave that occurred during the long, hot, summer of 1986, when multiple large-scale – and, frequently, violently repressed – strikes occurred throughout the province. Readers may have heard about or even attended alhi’s Calgary event, a Maria Dunn concert that was part of the Canadian Committee on Labour History’s workshop during the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences that year. Out on strike in 1986 were 1,100 McMurray Independent Oil Workers (miow) workers at suncor, in Fort McMurray; 200 International Woodworkers of America (iwa) workers at Zeidler Forest Products, in the town of Slave Lake and in Edmonton; and hundreds of Alberta Liquor Control Board workers across the province, members of the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (aupe).34 In addition, on 1 June, 1,300 meat packers represented by United Food and Commercial Workers (ufcw) at Fletchers in Red Deer and Gainers (Local 280-P) in Edmonton walked out.35

Arguably the most famous of these conflicts was the Gainers strike in Edmonton, which made national news because of the violence on the picket line between strikers, strikebreakers, and the police during the first weeks of June. Hundreds of people – ufcw members on strike, labour activists from other unions, and concerned citizens with no direct trade union connections – were arrested for refusing to obey court injunctions handed down to ensure that animals and strikebreakers could enter the Edmonton plant.36 The violence and desperation of the strike generated immense public pressure on the provincial government. In response to the Alberta Federation of Labour’s “Change the Law/Boycott Gainers” campaign, a Labour Legislation Review Committee was struck in late July.37 In largely conservative Alberta, working-class consciousness and solidarity was on the rise during the hot summer of ’86. Yet the final settlement of the Gainers strike, six and a half brutal and bitter months later in December, was worse than the agreement proposed by the Disputes Inquiry Board that the membership had rejected in July. In reality, the major victory was that the local avoided being destroyed by a hostile employer and an anti-labour government.38 The union did not succeed in regaining parity with other meat packers, as it had set out to at the beginning of the strike and as the strikers at Fletchers did in June.39 Furthermore, ufcw Local 280-P had to launch a lengthy court case to have members’ pensions reinstated, and even then, the company managed to steal the “surplus.”40

Commemorating the Summer of ’86

On 4 June 2016, alhi held a commemoration workshop event in Edmonton. During the event, local folk singer Maria Dunn performed her show “Packingtown” with Shannon Johnson, and Don Bouzek’s short documentary video Summer of ’86 (produced with Catherine C. Cole and Janice Melnychuck) was screened. The event also included short speeches by me and Lucien Royer, an Alberta Federation of Labour staff member in 1986. After a lunch break, participants broke into small discussion groups to address the lessons we could take from the Gainers strike and the summer of ’86: what worked, what did not, and how we could apply these lessons to struggles today.41 The event was well organized and well attended, and my impression was that people enjoyed participating. The group discussions were interesting, with a plurality of opinions among both the people who had been around during the strike and those who had not.

Based on my experience during the 2016 workshop, I found myself contemplating the nature and limitations of commemoration, which, beyond mere memorialization, implies a consideration of the origins and significance of an event. Can the critical aspects of commemoration – especially important for the working class still labouring under the burdens of capitalism – easily coexist with the celebratory elements when we collectively mark past conflicts? My major concern is the role of commemoration in class struggle: how can we evaluate the long-term ability of commemoration events to give workers a sense of their history and power? How well are our commemoration events raising class consciousness and building solidarity? Can commemoration of famous working-class battles help people in their own struggles today – that is, beyond the basic knowledge that resistance is not always futile? To be sure, asking these questions lends itself to the critiques of “presentism” addressed in the essay by John-Henry Harter. Yet, as Harter argues, presentist ways of thinking allow us to learn about working-class and labour history effectively, in a personal and lasting way. As the other roundtable presenters have examined, much of the political potential in learning working-class history is in how it both connects with people’s lived experience and fosters a sense of agency in the current period.

At the 2016 event, there was a tension between the celebratory aspects of the workshop – which lauded the solidarity, militancy, and bravery of the Gainers workers, a handful of whom were the guests of honour – and a critical evaluation of what went wrong. After all, the strikers sacrificed a great deal. To frankly ponder what actions might have led to a clear-cut victory, with the very people who had lost so badly, is an emotionally fraught conversation. It is affective labour, and skilled labour at that, to ensure that solidarity and not acrimony is the end result of such a discussion. There are contradictions between celebratory commemorations and critical assessments of historical events. Simply celebrating an event is not enough. However, a necessary precondition for critical analysis is a sufficient well of information. There was an obvious self-censoring in some of the main presentations at the alhi event – my own included – that did not criticize the actions of the ufcw during the 1986 strike. The national union in particular deserved censure for the way it interfered in local negotiations and the method of the final contract vote in December.42 The final contract was negotiated between Gainers owner Peter Pocklington and ufcw national representative Kip Connolly, with the help of Alberta premier Don Getty, who, six months into the strike, belatedly bestirred himself to take concrete action. At the meeting on 12 December 1986, strikers were presented with details of the deal but not allowed to ask questions, hear from their own local executive, or debate the matter.43 Given the real possibility of reforming labour laws and potentially coming far closer to parity for the workers, the agreement was not much of a deal.44 Most of the 2016 event, however, focused on the positives of the strike or simply the wider political context in Alberta. Narratives emphasizing the bravery of the workers were easy to find in the speeches, concert, and documentary, but the voices of workers disappointed and disillusioned by the strike and its aftermath were not as readily accessible.

At the event were strikers and allies who had been highly critical of the end of the strike when I interviewed them three and four years prior: people who had been disappointed by the settlement, angry with how the vote had taken place, disillusioned by the union, and frustrated by the sense that an opportunity had been lost. Criticisms over lack of transparency and democratic processes within the union and of a lack of courage and willingness to keep fighting for improved laws to benefit the whole working class in Alberta – or at least to hold out for parity – did emerge in the small group discussions in the afternoon. Whether these issues were raised, however, depended on whether a group included people who not only were present at and participated in the strike but also were willing to cast a cold light on the failings of the labour movement.

alhi held its workshop as close to the anniversary of the start of the strike as was feasible. June is a great time to celebrate the accomplishments of the Gainers strike: in 1986 it was a month of solidarity, militancy, and rising class consciousness in the province, when winning parity and reforming labour laws seemed possible.45 December, in contrast, is a terrible time to memorialize the strike, evoking the bitter disappointment of an inadequate settlement and the end of political pressure on the province’s Labour Legislation Review Committee to make changes to benefit workers. As Sam Davies notes, anniversaries inevitably lead to comparisons of the past and present, and “as the comparison seldom flatters the present,” they are often uncomfortable for the 21st-century labour movement.46

This is particularly true in Alberta today, where it is hard to imagine a strike such as the one at Gainers being the spark to ignite class consciousness and a widespread questioning of the province’s political economy. The common urge to recall struggles as victories, to celebrate and memorialize them, makes it hard in most cases to acknowledge how bad things are for workers in 2019. At Gainers, the plant shut down just over a decade after the strike, and the closure was preceded by more layoffs, concessions, and even harsher measures from the new employer. One draconian measure in particular witnessed the employer actively seeking to limit bathroom breaks for workers.47 Workers at Gainers never regained the material benefits they lost in 1984.48

The celebration aspect of the alhi event certainly affirmed the agency and class consciousness of the strikers in the past. The question is, did the event give participants a sense of their own power as workers in the present? Or was it an event of memorializing a single great moment in history with no resonance with their own class experience given the massive changes in work that have taken place since?49 Most workers in Edmonton today simply do not work in a comparable workplace: the majority labour in the service sector, the public sector, or the light industrial small shops in the oil-extraction service sector.50 These workplaces are not the same as a thousand-plus workforce in a Taylorized industrial setting rooted in a particular working-class community. Furthermore, Edmonton itself has changed drastically since 1986; with the city’s population growing by over 50 per cent, and its median age of 36, many Edmontonians and Albertans simply did not experience the Gainers strike.51 It is not part of their social memory.52

The actions of workers in the Gainers struggle are inspiring and a proud part of the province’s labour heritage – but only for the people who know about them. This is a good reason to commemorate the strike as alhi did, but it leads us to another, related issue. The people who attended the workshop event were predominantly those already active in their union – a self-selection of the more engaged and critical members of the labour movement. How do we expand the audience of such commemoration events? And once we succeed in popularizing working-class history – a difficult step on its own, but a crucial one according to most labour historians53 – how do we then make the leap to the sense of shared heritage and power that gives people the ability to imagine and strive for a different future?54 How do we give people inspiration beyond the day, or week, or month of an anniversary?

Issues for Critical Commemoration

One way to measure the success of an event is by how it galvanizes people into further action.55 While the June 2016 event was certainly the culmination of a great deal of hard work by many people, it did not necessarily translate into bringing new workers into the alhi fold or even into progress on the many issues raised by participants, like successfully pressuring the ndp government to improve labour laws.56 Bryan Palmer states in his discussion of the 1983 Operation Solidarity in British Columbia, “Heroes they were; victors they most emphatically were not.”57 The same can be said of the Gainers workers. It is easy to discuss what was accomplished during the strike (an upsurge of working-class consciousness that surprised everyone) but much harder to publicly and frankly appraise not just where the mobilization during the summer of ’86 fell short, but why. This is especially true when the people who fought and sacrificed are sitting in the front row or beside you at a table.

The event’s participants did an exemplary job of identifying a number of factors that contributed to the failure of the strike and that, discouragingly, have not been overcome in the 30 years since. These issues include scabbing (which is still permitted by law); the lack of union democracy and power of national and international unions over locals; tiered collective agreements that have, in fact, proliferated; and overall neoliberal ideas, which have only gained power in the years since the strike. The root of the problem – and the reason for the lack of progress on these fronts – was hinted at by some of the participants, who critiqued both the legal system in which unions are enmeshed and the lack of a brave vision by union leadership. That, however, was the deepest analysis offered, rather than the majority of the discussion. The preponderance of prosaic union practices and humdrum leaders is due at least in part to the lack of a revolutionary left inside the labour movement who might be counted on to encourage workers to imagine radical alternatives and assure them of their own power. Why are leaders not brave today? Because they are not challenged by rank-and-file activists. Furthermore, there was no acknowledgement that collective bargaining is failing to substantively improve workers’ lives today. At best it is only making small gains on familiar territory, not winning new rights for the working class. In many cases, however, collective bargaining is actually resulting in losses of real wages and the right to full-time work.

This brings us back to our original question: How can public commemoration help people with their struggles today and how can we ensure its lasting impact? First, it is crucial to have a critical perspective of past events. This is an area where historians are well suited to offer assistance. In a case like the Gainers strike, this means confirming that workers struggled valiantly but acknowledging that in the end they failed to win their original goal of parity. One obstacle to including a critical perspective in commemoration events is the extent to which even broadly organized events are still beholden to their sponsors. In the case of the alhi workshop, sponsors included the ufcw. While a single event may be conducted just as critically as its organizers please, there is an ongoing financial relationship between labour heritage organizations and the unions that fund their work.58 It is no surprise that labour heritage organizations and public historians are leery of offending sponsors, or that this concern can lead to self-censorship in order to maintain an amicable partnership.59

Second, it seems to be equally necessary to consider how commemoration events themselves succeed and in what ways they fail. In my opinion, one small step would be to incorporate participant responses to commemorative events. Immediately following its 2012 conference, for example, alhi conducted a survey to gauge what people enjoyed and what they learned from the conference. Surveys could occur immediately after a commemorative event, with a follow-up survey sent a year later. Even the rates of response could tell us something about how people experienced and connected to the event.

Finally, commemoration cannot be a “one and done” affair if it is to give workers a sense of their own history and power and to raise class consciousness and build solidarity. We need to find ways to ensure that commemoration is ongoing and relevant to workers’ lives today. One way to do that could be pushing for a new workers’ holiday in Alberta on 1 June. Another could be creating a worker-controlled pension plan open to workers across the province, unionized or not, perhaps called the Gainers Strike Trust Fund. That way, workers would not risk having their pension seized by their employer.

I continue to find the militancy and solidarity of the Gainers strike inspiring. Yet, the way the strike ended remains controversial. Given alhi’s praiseworthy framing of the commemoration event as an exploration of lessons we could take from the Gainers strike and how to apply them to current struggles, there is little benefit to exploring only the laudatory portions of the history. The less-than-salubrious aspects of the strike provide equally important lessons for class struggle in the present. Just one example is the vital importance of fighting for local rank-and-file control of decision-making during a labour dispute, as opposed to strike actions being dictated from above by distant union bureaucrats.60 Finally, we should take to heart one particular message that came out of alhi’s workshop report: “Don’t be afraid to push for a greater vision.”61

I would like to say thank you to the people at the Alberta Labour History Institute for the tremendous work they do in commemorating and preserving Alberta’s rich working-class past.

1. E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963; London: Penguin, 1991), 11.

2. For a brief discussion of industrial legislation and its impact on labour, see Mark Leier, “Dissent, Democracy, and Discipline: The Case of Kuzych versus White et al.,” in Eric Tucker & Judy Fudge, eds., Work on Trial: Cases in Context (Toronto: Osgoode Law Society and Irwin, 2010), 111–142.

3. George Lakey, How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning (New York: Melville House, 2018).

4. Eugene Debs, “Industrial Unionism” (1905), Marxists Internet Archive, December 2003, https://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1905/industrial.htm.

5. On the free speech fight, and the schisms in the labour and left movements, see Leier, Where the Fraser River Flows: The Industrial Workers of the World in BC (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1990).

6. See “Tornado Warning: Four Roles of Social Change,” Training for Change website, n.d., https://www.trainingforchange.org/training_tools/tornado-warning-four-roles-of-social-change/.

7. Thanks to Dale McCartney for pointing this out to me during the exercise.

8. See Daniel Hunter & George Lakey, Opening Space for Democracy: Third-Party Nonviolent Intervention, Curriculum and Trainer’s Manual (Philadelphia: Training for Change, 2004), 21.

9. William Bigelow & Norman Diamond, The Power in Our Hands: A Curriculum on the History of Work and Workers in the United States (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1988).

10. “Solidarity Forever,” lyrics by Ralph Chaplin, ca. 1915, Industrial Workers of the World website, https://www.iww.org/history/icons/solidarity_forever.

11. Lynn Hunt, “Against Presentism,” Perspectives on History: The Magazine of the American Historical Association, 1 May 2002, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2002/against-presentism.

12. David Davenport, “Presentism: The Dangerous Virus Spreading across College Campuses,” Forbes, 1 December 2015, https://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddavenport/2015/12/01/presentism-the-dangerous-virus-spreading-across-college-campuses.

13. On debates for and against presentism in evaluating Canadian history, see David Moscrop, “Rewriting History? That’s How History Is Written in the First Place,” Maclean’s, 25 August 2017, https://www.macleans.ca/opinion/rewriting-history-thats-how-history-is-written-in-the-first-place/; Sean Carleton, “John A. Macdonald Was the Real Architect of Residential Schools,” Toronto Star, 9 July 2017. For a specific case of statue removal, see “John A. Macdonald Statue Removed from Victoria City Hall,” cbc News, 11 August 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/john-a-macdonald-statue-victoria-city-hall-lisa-helps-1.4782065.

14. Hunt, “Against Presentism.”

15. Hunt, “Against Presentism.”

16. Ester Reiter, Making Fast Food: From the Frying Pan into the Fryer, 2nd ed. (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000).

17. Judy Willis, Research-Based Strategies to Ignite Student Learning (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development), Chap. 1, http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/107006/chapters/Memory,_Learning,_and_Test-Taking_Success.aspx.

18. Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning, How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000).

19. Jasmin M. Kizilirmak, Joana Galvao Gomes da Silva, Fatma Imamoglu & Alan Richardson-Klavehn, “Generation and the Subjective Feeling of ‘Aha!’ Are Independently Related to Learning from Insight,” Psychological Research 80, no. 6 (2016): 1059–1074.

20. Kizilirmak, Galvao Gomes da Silva, Imamoglu & Richardson-Klavehn, “Generation,” 1060.

21. Thanks to Mark Leier for this suggestion.

22. Timothy J. Rahilly & Bev Hudson, “Canada’s First International Partnership for a Pathway Program,” in Cintia Inés Agosti & Eva Bernat, eds., University Pathway Programs: Local Responses within a Growing Global Trend (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International, 2018), 267–285, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72505-5; Dale M. McCartney & Amy Scott Metcalfe, “Corporatization of Higher Education through Internationalization: The Emergence of Pathway Colleges in Canada,” Tertiary Education and Management 24, 3 (2018): 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2018.1439997.

23. Canadian Bureau for International Education, “Canada’s Performance and Potential in International Education: International Students in Canada, 2018,” infographic, accessed 13 August 2019, https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Infographic-inbound-EN.pdf.

24. Henry Decock, Ursula McCloy, Mitchell Steffler & Julien Dicaire, “International Students at Ontario Colleges: A Profile,” CBIE Research in Brief no. 6, Ottawa, October 2016, https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/FINAL-CBIE-Research-in-Brief-N6.pdf.

25. Lisa Ruth Brunner, “Higher Educational Institutions as Emerging Immigrant Selection Actors: A History of British Columbia’s Retention of International Graduates, 2001–2016,” Policy Reviews in Higher Education 1, 1 (2017): 22–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2016.1243016.

26. David Noble, “May 2007: Giving Up the Grade,” The Monitor, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, May 2007, https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/monitor/may-2007-giving-grade.

27. Jim Cummins, Vicki Bismilla, Sarah Cohen, Frances Giampapa & Lisa Leoni, “Timelines and Lifelines: Rethinking Literacy Instruction in Multilingual Classrooms,” Orbit 36, 1 (2005): 22–26.

28. Peter D. Macintyre, Richard Clément, Zoltán Dörnyei & Kimberly A. Noels, “Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation,” Modern Language Journal 82, 4 (1998): 545–562, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x.

29. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 2000), 79.

30. John Lutz, “After the Fur Trade: The Aboriginal Labouring Class of British Columbia, 1849–1890,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 3, 1 (1992): 69, https://doi.org/10.7202/031045ar.

31. George Lakey, Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for Success with Diverse Adult Learners, 1st ed., Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010), 14.

32. Herbert Kohl, “I Won’t Learn from You,” in “I Won’t Learn from You” and Other Thoughts on Creative Maladjustment (New York: New Press, 1994), 32.

33. Mark Leier, “Teaching the Work Process and ‘Deskilling’ with the Paper Airplane Game,” ActiveHistory.ca (blog), 1 June 2018, http://activehistory.ca/2018/06/teaching-the-work-process-and-deskilling-with-the-paper-airplane-game/.

34. Deborah Radcliffe, “Understanding Labour Law Reform in Alberta: 1986–1988,” PhD diss., University of Alberta, 1997, 90–92.

35. McMurray Independent Oil Workers (miow) in Fort McMurray walked out 1 May; International Woodworkers of America Local 1-20 at Slave Lake and the smaller plant in Edmonton had been out for over a year, Fletchers and Gainers both struck on 1 June, and Alberta Liquor Control Board workers went on strike 31 July. See Winston Gereluk, “Alberta Labour in the 1980s,” in Alvin Finkel, ed., Working People in Alberta: A History (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2012), 185–205.

36. A second, more restrictive injunction limiting the picketers to 42 members of ufcw and making it illegal for any group of more than three people to gather in the vicinity of the struck plant was granted ten days into the strike, after police superintendent Robert Claney complained that the first injunction did not allow the police “to clear the area and then move some transport in and out.” cbc tv evening news, Edmonton, 9 June 1986; “Curbs Tightened on Pickets,” Edmonton Journal, 11 June 1986.

37. The Labour Legislation Review Committee went on a time-wasting international tour, undoubtedly in the futile hope the strike would be settled by the time they returned. The committee spent over $500,000 – more than double its budget. Radcliffe, “Understanding Labour Law Reform,” 119.

38. Owner Peter Pocklington stated, in an interview broadcast on the cbc radio program Edmonton AM, on 5 June, that his plant would “be non-union.” “cbc Interview,” Edmonton Journal, June 6, 1986.

39. Alex Dubensky, “Findings and Recommendations of the Disputes Inquiry Board Report,” attachment to Government of Alberta news release, 10 July 1986 (2:30 p.m.).

40. For more information, see Alain Noël & Keith Gardner, “The Gainers Strike: Capitalist Offensive, Militancy, and the Politics of Industrial Relations in Canada,” Studies in Political Economy 31, 1 (1990): 31–72; Gereluk, “Alberta Labour,” 191–192; Andrea Samoil, “Class Struggle and Solidarity in Neo-Liberal Times: The 1986 Gainers Strike,” ma thesis, Trent University, 2014; David May, The Battle of 66th Street: Pocklington vs ufcw Local 280P (Edmonton: Duval House, 1996).

41. See “Summer of ’86 Workshop Report,” alhi website, accessed 13 August 2019, http://albertalabourhistory.org/78-2/summer-of-86-workshop-report/. Pictures of the event can be found at Alberta Labour History Institute, “Summer of ’86,” photo album, Facebook, 7 June 2016, https://www.facebook.com/pg/Alberta-Labour-History-Institute-234873849869503/photos/?tab=album&album_id=1167130959977116.

42. Dave Werlin commented, “We put them [ufcw national] in a spot that they didn’t want to be in. How many times did they fly some bugger in here from Toronto to try to end it?” Interview by author, 20 August 2012, Edmonton.

43. The final deal was summarized in a positive light in the Summer of ’86 documentary, though my personal interviews of strikers and news coverage from the time demonstrate that workers were deeply unhappy about the settlement. Furthermore, there is a difference between the sensationalist noting of Renee Peavey saying the workers were “fucked” on the national news and an analysis and critique of the international union’s behaviour. Kim McLeod, “No Cheers from Pickets at Gainers,” Edmonton Journal, 13 December 1986; McLeod, “Settling of Strike Leaves Bitterness for Some Strikers,” Edmonton Journal, 15 December 1986; Mindelle Jacobs, “Union Says Yes to Pact: Puck Wins Battle,” Calgary Sun, 15 December 1986.

44. For more details on the settlement, see Samoil, “Class Struggle and Solidarity,” 143–152.

45. The act of remembering is, simultaneously, an act of forgetting. Istvan Rév argues, for instance, “History writing is never born of only remembering; the forgetting, the discarding of elements that can’t be fit into the new history are just as much a part of the reconstruction of history as remembering.” Quoted in Richard S. Esbenshade, “Remembering to Forget: Memory, History, National Identity in Postwar East-Central Europe,” in Stephen Greenblatt, István Rév & Randolph Starn, eds., “Identifying Histories: Eastern Europe before and after 1989,” special issue, Representations, no. 49 (Winter 1995): 86.

46. Sam Davies, “Remembering the 1911 General Transport Strike in Liverpool,” in Dennis Deslippe, Eric Fure-Slocum & John W. McKerley, eds., Civic Labors (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 93.

47. There were layoffs in 1993 on the beef line, a three-year wage freeze accepted the same year to ensure the plant stayed open under Burns ownership, and a penalty of one dollar per trip to the bathroom outside workers’ scheduled breaks in 1994. By 1997, Gainers had a base rate lower than plants in Red Deer and Winnipeg and it took longer to reach the top of the pay scale, at seven and a half years. At every negotiation since 1986, the various employers had threatened workers with plant closure if workers did not accept concessions. In 1997, Maple Leaf Foods carried through and the plant was torn down. See Samoil, “Class Struggle and Solidarity,” 153–162.

48. In 1984 the union was strong-armed by a literal lineup of strike breakers outside the plant gates into accepting concessions drastically below the national pattern. On the end of national pattern bargaining in meat-packing (and the role of Burns and Gainers in this), see Anne Forrest, “The Rise and Fall of National Bargaining in the Canadian Meat-Packing Industry,” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations 44, 2 (1989): 393–408.