Labour / Le Travail

Issue 84 (2019)

article

The Employment Standards Enforcement Gap and the Overtime Pay Exemption in Ontario

Introduction: Employment Standards and the Problem of Exemptions

While employment standards (es) legislation is designed to provide a general set of minimum standards for a labour market, it often includes exemptions and special rules that subject specified categories of workers to selective treatment. Differential treatment under es is typically justified in relation to the particularities of sector, industry, or occupation, often leading to a lowering or an absence of regulatory protections for the given group of workers. With the rise in precarious employment across industrialized labour markets – characterized by growing levels of uncertainty, lack of control over the labour process, limited access to regulatory protection, and low income – the question of exemptions and their connection to precarious employment has received attention in recent scholarship.1 This attention points to the ways in which exemptions may contribute to the exclusion from labour and employment laws of already marginalized groups of workers, thereby heightening their precariousness. Guy Davidov locates this tendency within a legislative “coverage crisis” that has grown over the last several decades of neoliberalism.2 Positing that coverage by labour and employment laws can be understood on a continuum from universality to selectivity, Davidov asserts that in recent decades, there has been a shift back toward greater selectivity in terms of establishing coverage. Coupled with labour-market change that has altered employment structures, in many national contexts this shift has resulted in growing numbers of workers left outside the scope of labour and employment laws. This omission affects workers in new forms of employment relationships: for example, those (mis)classified as independent contractors; those who are highly marginalized in more traditional forms of employment, such as migrant workers in agricultural, domestic, and caregiving work; and many in between. In the Canadian context, scholarship examining exemptions of agricultural workers from occupational health and safety legislation and collective bargaining, and of temporary migrant workers from labour relations and es legislation, has noted such tendencies.3

Set in the context of Ontario, Canada, this article explores the connections between es exemptions and precarious employment through the study of the overtime pay exemption in the province’s Employment Standards Act (esa).4 Ontario’s esa was designed to provide minimum employment standards for the majority of workers in the province, in particular for those with limited bargaining power. In addition, the esa was initially characterized by the Ontario Ministry of Labour as an attempt to promote the adoption of “socially desirable” conditions of employment.5 Thus, minimum es legislation was conceived as a form of workplace protection for those most vulnerable to employer exploitation in an unregulated market and, as such, a means to raise standards in the labour market more generally. At the time of the enactment of the esa, the government claimed that the legislation was intended to provide protection against exploitation while it simultaneously constructed the act to account for variations in types of work, by industry and by sector through exemptions and special rules, responding, in part, to employer resistance to a universal approach to the regulation of minimum employment standards.

Despite a commitment to extend legislative coverage as widely as possible, the system of exemptions became a key way to accommodate employers’ prerogatives for flexibility in the organization of work and its cost.6 This article examines the system of exemptions as it developed in Ontario from before the enactment of the esa in 1968 to the present. After constructing an overview of exemptions and their scope, we develop a case study of exemptions to the overtime pay provision of the esa and its regulations and examine three sectors in which exemptions apply, focusing on the development of the specific exemption, its rationale, and its implication for workers who are subject to it.7 The focus on overtime pay has been selected for a number of reasons: it cuts across many different industries as well as both the public and private sectors; it impacts the conditions of employment for workers in precarious jobs; and it has long been viewed as an important balancing mechanism that supports workers’ rights. Through this study of the overtime pay exemption, the system of exemptions is presented as a contradictory approach to the regulation of employment standards that, in effect, reduces es coverage, contributes to the avoidance of key standards in the act, and undermines the goal of providing protection for workers in precarious jobs. More broadly, we consider the extent to which legislative and regulatory exemptions may contribute to what has elsewhere been termed the es enforcement gap, stemming from interrelated processes of es violation, evasion, erosion, and abandonment.8 The article concludes with a discussion of regulatory strategies designed to counter the precariousness generated through legislative exemptions.

Hours of Work and Overtime Exemptions in Ontario’s ESA

Exemptions have been a part of Ontario’s esa since its inception and, as we shall see, drew on a longer history of exemptions from minimum-standards laws. In principle, the aim of the esa was to establish a (somewhat) universal and “socially and economically acceptable” floor for certain minimum conditions of employment, as governments sought to respond to demands from workers, trade unions, and labour federations, as well as middle-class social reformers, for legislative workplace protection.9 This floor was designed, in particular, for workers who had “limited bargaining power” and to combat poverty that may result from low wages.10 In practice, however, and in response to lobbying efforts by business in periods of legislative development, the form of es regulation created by the Ontario government also sought to accommodate varying business conditions in the construction of that floor. Specifically, in an attempt to create a balance between the “socially and economically acceptable,” the government aimed to ensure that businesses in the province would not be detrimentally impacted by es legislation and to assuage business community concerns regarding the need to develop minimum standards that would accommodate particularities of industry and sector.11

While this article focuses on the overtime pay exemption of the current Ontario esa, it is instructive to briefly review some exemptions in earlier provincial minimum-standards legislation, with attention to those that pertain to hours of work and overtime, as these are illustrative of the logic and processes that produced the contemporary overtime pay exemption. The earliest working-time regulation in Ontario dates to Lord’s Day legislation enacted in 1845, which prohibited a range of activities on Sundays, including employment. The original statute, applicable in Upper Canada only, exempted “works of necessity and works of charity.”12 It was later held that because these laws regulated morality and thus were criminal in nature the federal government, not the provinces, had jurisdiction, and it responded in 1906 by enacting a federal Lord’s Day Act. Although the law contained numerous exemptions, they tended to be narrowly drawn.13 Secular working-time regulation in the province dates to the Factories Act of 1884, which regulated the working time of women and children, setting 60 hours as a weekly maximum. The Factories Act was developed during a period of growing pressure for the regulation of working time – as a result of the Nine-Hour Movement of the previous decade – as well as the efforts of the labour movement and middle-class social reformers advocating for social protection for working women and children.14

The 1944 Hours of Work and Vacations with Pay Act (hwvpa) was the first working-time legislation in the province to apply to adult workers, both male and female.15 Introduced at the end of World War II, the hwvpa emerged in a context of rising labour unrest in Canada, with a major strike wave toward the end of the war, and alongside postwar labour relations legislation that established collective bargaining rights.16 The hwvpa established maximum hours of work at 8 per day and 48 per week for employees in all industrial undertakings, as well as an annual paid vacation of one week and the right to refuse overtime.17 In that regard, it can be viewed as an example of the arc of protective labour law from the specific to the universal discussed by Davidov.18 However, the extent of that shift should not be overstated because, consistent with the aim to not excessively burden businesses with government regulation, the hwvpa itself excluded supervisors and confidential employees (s. 3), allowed the board to authorize collective agreements that established different standards (s. 4), allowed war industries to be exempt (s. 5), allowed excess hours in the case of accidents or emergencies (s. 6), permitted regulations to be made creating further exemptions (s. 10), and authorized the board to grant ad hoc exemptions upon application in the interim between the time the act came into force on 1 July and the end of the year (s. 14). Pursuant to these powers, even before the act came into force, the Minister of Labour excluded war industries (including textiles, which, for the purposes of avoiding wartime collective bargaining regulations, had itself declared not to be a war industry). The minister also consulted various industrial associations and agreed that special arrangements would be made for hotels, retail shops, and restaurants.19 When regulations were drafted later that year, numerous additional exemptions were created, including ones based both on the nature of the industry or sector and on the recognition of a range of special circumstances. For example, the hours-of-work maximums could be exceeded in the event of an accident, the need for emergency work, or due to the “perishable nature” of raw materials. The daily 8-hour maximum could be exceeded so long as an employer did not exceed the weekly 48-hour limit. The regulations also permitted up to 120 hours of overtime work per year, though there was no overtime rate at that time. Finally, there were numerous occupationally specific exemptions, including for professionals and persons employed in farming, commercial fishing, firefighting, domestic service, and the growing of flowers, fruits, and vegetables. Also exempted were funeral directors and embalmers, fishing and hunting guides, live-in caretakers, and police.20

In setting general limits of hours of work, the hwvpa made a significant contribution to the establishment of a minimum-standards floor for workers in the province. However, the breadth of industry and occupational exemptions, as well as the variety of special rules and excess-hours permits – which were reported to be easily accessible – undermined the universality of the act.21 The Ontario Task Force on Hours of Work and Overtime (tfhwo), which in the mid-1980s conducted the first major review of overtime and hours-of-work regulation since the esa was established, noted this tendency: “The greater stringency of the vastly extended coverage and the more stringent maximums at eight hours per day and 48 per week were offset, in part at least, by greater flexibility through extensive exemptions and by downplaying the eight-hour-per-day maximum where longer hours were the custom.”22

In the mid-1960s, and in the context of rising pressure from the labour movement in Ontario for stronger legislative protections in the workplace as well as for legislating minimum labour standards at the federal level, the Ontario government began exploring the development of new minimum standards legislation that would combine and update the existing patchwork of legislative standards, including in the area of working-time regulation.23 While there were calls from Ontario’s unions for a legislated 40-hour workweek, the government was steadfast in its opposition. A memorandum in 1968 stated that “to limit hours to 40 would not only hobble industry, but would also limit workers’ opportunities to earn overtime pay, which would reduce their incomes.”24 The province also began considering the introduction of a legislated overtime premium, Ontario being one of the few North American jurisdictions without one at the time.25

In 1968, the province enacted the esa, which took effect on 1 January 1969.26 The act set standards regarding minimum wages, hours of work, overtime, vacations with pay, and equal pay for equal work. Though the act was intended to apply to most workers in the province, and particularly those with the least bargaining power, it also sought to strike a balance between social protection and business interests.27 To this end, and like the hwvpa, the esa contained numerous exemptions and special rules, including in the regulation of hours of work and overtime.28 For example, managerial and supervisory employees were excluded from hours-of-work restrictions, and the daily-hours maximum could be exceeded so long as the weekly limit was not. In the event that an employer maintained a normal workday longer than 8 hours but a workweek of 48 hours or less, the right to refuse overtime would not apply. A permit system allowed for overtime hours to an annual maximum of 100, with the director of employment standards able to authorize further hours depending on the “special nature of the work performed,” or the “perishable nature of the raw material being processed.”29

The regulations made under the esa contained many occupationally specific exemptions as well, again including a number that pertained to working time.30 The general regulation excluded regulated professionals, teachers, “commission salesmen,” persons engaged in fishing or farming, domestic servants, and secondary students from all protections except equal pay and pay statement requirements. Managerial and supervisory employees were exempt from the overtime pay provisions, as were telephone company employees, fishing and hunting guides, agricultural workers who were not employed in farming as defined in the regulation, home workers, students looking after children, and resident superintendents in residential buildings.31 Another nine regulations, promulgated at the same time, created special overtime rules for specific occupations. For example, ambulance and taxi drivers were totally exempt, whereas highway transport drivers and seasonal fruit and vegetable processing workers became entitled to overtime pay after 60 hours and local cartage drivers, hotel workers, and some road-building employees got overtime pay after 55 hours.32 Other road-building employees got overtime at 50 hours, as did sewer and water-main workers, and interurban transport drivers got overtime after 48 hours.

As the esa developed through the 1970s and 1980s, five categories of legislated exemptions became apparent: (1) those entirely excluded from the act; (2) those exempt from all working-time and paid-holiday arrangements; (3) those exempt from specific provisions of the act, including some or all working-time provisions;33 (4) those covered by special overtime provisions allowing for an overtime premium to begin at a threshold exceeding 44 hours (e.g. 50 hours); and (5) those covered by special permits allowing employers to exceed the maximum-hours standards.34 Despite the aim of the esa to extend its coverage “to the greatest possible number of employees in Ontario,” the tfhwo, struck partly in response to growing pressure from Ontario’s labour movement to improve the regulation of working time, estimated that 866,000 employees – representing approximately 25 per cent of Ontario’s paid employees – were exempt from the hours-of-work provisions in 1986 and some 728,000 employees, or approximately 21 per cent of the paid workforce, were exempt from the overtime provisions.35 Similarly, in the early 2000s, the Ontario Federation of Labour estimated that approximately 20 per cent of Ontario workers were exempt from some or all of the esa.36

As discussed, the system of exemptions was constructed to account for particularities of occupations and industries. From the perspective of the Ministry of Labour, the “universal application of all the basic standards is not seen as possible” because “variations in terms of employment, types of work, and characteristics of certain industries will always require some exceptions.”37 Particular conditions, such as irregular hours, unanticipated factors that may make hours unpredictable, emergencies, and employment status, were accounted for in developing the exemptions.38 Exemptions were also meant to both limit the government regulation of employer-employee-negotiated working-time arrangements and avoid the imposition of “severe hardships” on employers.39 The exemptions had often reflected the lobbying efforts of various employer associations that emphasized the unique aspects of a particular occupation – in terms of seasonal employment, for example, or of the potential impact of the esa on the financial viability of a given business.40

In addition to the various explicit exemptions from the legislated standards in the original esa, a system of special permits provided another way in which employers were able to exceed working-time standards.41 Like the exemptions themselves, the special permits were introduced to account for occupational and industry variation in work hours, so that universal standards did not constrain particular sectors where long hours were prevalent or where seasonal variation in production required some flexibility in scheduling.42 Permits took four forms: extended daily hours (to a maximum of 12); excess annual hours (to a maximum of 100 extra overtime hours per year); extended excess annual hours, permitting the scheduling of additional overtime (on top of the 100 hours) in the event of exceptional circumstances; and industry permits that allowed for excess overtime hours in 26 industries, including construction, ambulance service, automotive repair and gasoline service stations, baking, fruit and vegetable processing, highway transportation, hotels/motels, restaurants and taverns, mining, retail stores, and taxis.43 The industry permits extended the regular work day to 10 hours and permitted additional overtime hours on top of the 100 excess annual hours for some employee groups, though they did not exempt employees from overtime premium pay.44 The permit system was easily accessed by employers, meaning the esa’s cap on regular working hours (daily and/or weekly) was exceeded with little interference from the Ministry of Labour.45

The tfhwo, established in a context of growing layoffs and unemployment for some and the persistence of excessive overtime for others, expressed concern that the underlying principle of universality was being “traded off against the desires of any employer” owing to the ease with which the permits were issued.46 In essence, the permits system, which enabled employers to avoid the hours-of-work limits established by the esa, contributed to the erosion of the floor set by the esa. The task force recommended that the Ministry of Labour review special rules and exemptions from hours-of-work standards with the aim to limit exceptions and minimize special treatment. This recommendation was not adopted by the Liberal government that held office at the time, nor by subsequent governments in the 1990s.47

In 2000, the provincial Progressive Conservative government introduced significant changes to the esa: the esa 2000 increased the maximum weekly hours of work from 48 to 60 and expanded the practice of overtime averaging, which allowed for the calculation of entitlement to overtime pay to be averaged over a period of up to four weeks; it also replaced the excess-hours permits system with a requirement that work over 48 hours per week be subject to written agreement between employee and employer and introduced the same provision for “employee consent” to overtime averaging.48 With the new forms of working-time flexibility introduced through the increased weekly maximum and overtime averaging provisions, as well as the aforementioned provisions regarding “employee consent,” the esa 2000 contributed to enhancing employer control over time for those workers in precarious jobs.49 Subsequent Liberal government reforms in 2004 did not alter this trend.50

The failure to address the problem of exemptions produced the situation we outline below, both in general terms and with a focus on the overtime pay exemption and special rules.

Contemporary Overtime Exemptions and Special Rules in Ontario

Broadly speaking, several categories of workers fall outside the scope of coverage of Ontario’s esa, including the self-employed; individuals who hold political, judicial, religious, or elected trade union office who are not considered employees under common law tradition; police officers; and those in work programs under Ontario Works or work programs involving young offenders or inmates. The esa also exempts employees who work in a federally regulated sector and who are covered under Part iii of the Canada Labour Code. For those assumed to be formally covered by workplace standards, the reality is less a uniform floor of workplace rights than it is a complex patchwork of exemptions and special rules that have been incorporated into the act over time “to introduce a degree of flexibility into the legislation which would serve the needs of employers operating in a competitive market.”51 An employee’s coverage under the esa hinges on a number of factors, including the type of job he or she performs, the length of job tenure, the characteristics of employers (namely, firm and payroll size, continuous operation status, and temporary agencies), and the personal characteristics of employees themselves (e.g. students).52 Taken together, these exemptions and special rules result in a patchwork of coverage leading to tenuous workplace protections for a large proportion of workers in Ontario.

In the area of overtime pay, most exemptions are occupationally specific and are detailed in regulation 285 of the esa. These include complete exemptions from overtime pay for travelling commissioned salespersons, information technology professionals, landscape gardeners, residential care workers, those employed to install or maintain swimming pools, residential building superintendents, janitors and caretakers, ambulance drivers and first aid attendants, and farm employees involved in harvesting fruits and vegetables, among others. Full exemptions also exist for a wide range of professionals including doctors and public accountants. Additionally, partial overtime pay exemptions – typically enacted in higher thresholds for overtime premiums – also exist for employees in certain occupations. Those engaged in road, highway, or parking lot construction and maintenance are entitled to overtime after 55 hours of work. Employees involved in the construction of bridges and tunnels are entitled to overtime pay after working 50 hours. And, once again, employees in supervisory positions are exempt from overtime pay. Other partial exemptions apply on the basis of workplace characteristics, where a higher overtime pay threshold (of 50 hours) is reserved for employees in hospitality industry workplaces who are provided with room and board and who work no more than 24 weeks for the employer per year.53 Finally, a limited number of full exemptions to overtime pay apply on the basis of personal characteristics of employees. Students who are employed at a children’s camp, employed to instruct children, or employed in a recreation program run by a registered charity are also exempt from overtime pay.

As discussed, full and partial overtime pay exemptions run counter to the putative legislative intent behind the original esa to provide a broad floor of minimum protections.54 Indeed, findings from a recent statistical analysis of esa exemptions reveal the full extent of overtime coverage inequities among Ontario employees.55 Only four out of every five employees enjoy the full benefit of overtime pay protections, while others are subject to full or partial exemptions. As a result, it is inappropriate to think of overtime pay as a universal minimum protection. Ultimately, overtime exemptions facilitate excessive hours without the right to refuse, which undermines job stability, job creation, and the development of gender-equitable working-time arrangements that allow men and women to balance work and caregiving responsibilities.56

Looking further to the situation in 2016, we use Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (lfs) to examine non-unionized employees – the population of interest, because they are in occupations regulated by the esa.57 Our analysis focuses only on people’s main job in each year (for those who work multiple jobs, this is the job in which they worked the most hours). People working in jobs that are fully or partially exempt from overtime pay provisions were identified using the standardized industry (North American Industry Classification System [naics 2007]) and occupation (National Occupational Classification [noc-2011]) codes provided in the lfs, matched with the information provided in the Ontario Ministry of Labour’s online Special Rules and Exemptions tool.58

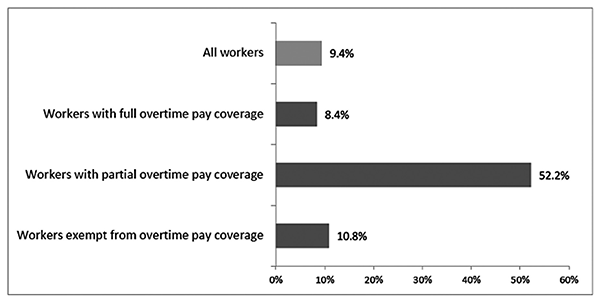

Overall, 9.4 per cent of non-unionized Ontario employees reported working more than 44 paid hours in the reference week (see Figure 1).59 Employees in occupations that are fully or partially exempt from the esa’s overtime pay provisions were more likely than employees in occupations with no exemptions to work overtime, with 10.8 per cent and 52.2 per cent, respectively, reporting that they worked more than 44 hours in the reference week. Partially exempt employees can work up to 6 additional hours each week (from 44 to 50 hours) without full remuneration; after 50 hours, the overtime pay provision is in effect.60

Figure 1. Percentage of non-unionized employees who worked more than 44 hours in reference week.

The number of overtime hours that people with full and partial exemptions worked varies widely. On average, of the employees in industries that are partially exempt from the overtime pay provision who worked any overtime hours in the reference week, they worked an average of 13.3 overtime hours. Among this group, 16.6 per cent worked less than 6 additional hours, 37.8 per cent worked between 6 and 12 additional hours, and 45.6 per cent worked 12 or more additional hours in the reference week. Of the partially exempt employees who worked more than 6 additional hours, most are in transportation and some are in construction. Employees in industries that are fully exempt who worked any overtime hours in the reference week worked an average of 8.6 hours overtime hours. Among this group, 37.1 per cent worked less than 6 additional hours, 37.7 per cent worked between 6 and 12 additional hours, and 25.3 per cent worked 12 or more additional hours in the reference week.

Overtime pay exemptions have a substantial cost to workers in terms of lost income. As a result of these exemptions, Ontario employees who worked overtime in industries that are partially or fully exempt from the overtime pay provisions of the esa potentially lose an average of 6.6 per cent of their weekly wage in their main job.61 Employees in industries that are fully exempt lose an average of 7.3 per cent of their weekly wage because of these exemptions, and those in industries that are partially exempt lose an average of 4.7 per cent of their weekly wage. Overall, 74.1 per cent of employees who work overtime in industries that are partially or fully exempt from overtime pay regulations lose 4 per cent or more of their weekly pay in lost overtime premiums; notably, these workers are losing the equivalent of their vacation pay (or more) to overtime pay exemptions.

Since the esa’s overtime pay exemptions are based on occupation and industry, it is unsurprising that clear sectoral trends exist in terms of who is working overtime that may not be fully remunerated. In terms of occupation, they are most likely to be in occupations unique to primary industry, trades and transport occupations, and management occupations. Overall, those who perceive their job as managerial are more likely to be working overtime that may not be fully remunerated, likely because of the managerial exemptions embedded in the esa. In relation to industry, those working overtime who may not be fully remunerated are most likely to be working in agriculture, transportation and warehousing, and construction.

Overall, it is clear that these broad and ad hoc overtime pay exemptions have a substantial effect on workers in the province. Among the 2.6 per cent of non-unionized Ontario employees who report working overtime that may not be fully remunerated, roughly 730,000 hours a week are worked for which workers are not being fully paid, representing a net gain for businesses and a clear loss to workers. Workers may be collectively shorted more than $11 million weekly in lost wages in their main jobs because of esa exemptions for overtime pay.62 Rather than ensuring universal minimum protection, the esa overtime pay rules contribute to both a substantial loss of income for affected workers and a more general erosion of the overtime pay provision of the esa.

Sectoral/Occupational Profiles

We now turn to three cases to explore these dynamics in closer detail: agricultural workers, managers, and truck drivers, all of whom are deeply affected by the overtime pay exemption and/or special rules.

The Farm Worker Exemption

The exemption of farm workers from protective labour and employment law is so long-standing and pervasive that the term “farm worker exceptionalism”63 has been coined to describe their situation.64 Minimum standards regulating hours of work and minimum wages were largely a creature of the twentieth century, although early health and safety laws, such as the Factories Act, did set maximum hours of work for women and children. However, health- and safety-based regulation of working time never reached agricultural workers. The first working-time law to protect farm workers was Lord’s Day legislation, mentioned earlier. The 1845 provincial act only exempted “works of necessity and works of charity” and made no specific mention of farm work. The federal law enacted in 1906 contained the same exemption but also listed specific instances of such work. Although the law contained numerous exemptions, they tended to be narrowly drawn; for example, rather than exempting farm labourers as a class, the law excluded “the caring for milk, cheese, and live animals.”65

The agricultural workers exemption in the esa can be traced to the 1944 hwvpa, discussed earlier. The act itself did not exempt farm workers, but it allowed exemptions to be made by regulation and empowered the board administering the act to issue interim exemptions until the end of the year. As well, it permitted the exemption of war industries, and when announcing that the power would be exercised, Charles Daley, the Minister of Labour, included agriculture.66 Following the end of hostilities, it was announced that the war industries exemption would be cancelled effective 1 November 1945, but on 19 November a new regulation under the hwvpa was filed that listed a number of occupational exemptions, including farm workers.67 In 1952, the regulation was amended to exclude persons employed in the cultivation of flowers, fruits, or vegetables.68 The situation remained unchanged over the following decades. Not surprisingly, when the minimum-standards regime was expanded in 1968, farm worker exceptionalism continued, yet in a somewhat more nuanced fashion. Farm workers in general were excluded from the esa, except with regard to its equal pay, wage protection, and enforcement provisions. However, the definition of farming was modified to exclude many of its more industrial operations in which permanent employees were hired, such as egg grading, flax processing, greenhouse and nursery operations, and mushroom growing. Workers in these identified industries, therefore, were covered by the esa, but they were subject to specific exemptions, which included exclusion from the act’s hours-of-work and overtime provisions. Seasonal workers employed in fruit and vegetable processing were subject to a separate regulation that entitled them to overtime pay after 60 hours, instead of 48 hours – then the norm under the act.69 There have been some minor tweaks since that time, but the picture has not changed fundamentally. Current regulations exempt farm workers engaged in primary production from most protections, subject to special rules for vegetable, fruit, and tobacco harvesters (rules that do not include an entitlement to overtime pay). As well, workers in related areas not captured by the more general exclusion are specifically exempted from hours-of-work and overtime pay provisions, including those employed in the growing of mushrooms, flowers, sod, trees, and shrubs, breeding and boarding of horses, and keeping of fur-bearing animals.70

To date, we have not found evidence of any challenge being made to these exemptions or of any serious attempt to justify them.71 John Kinley, who in 1987 wrote the first detailed analysis of the farm worker exclusion from the work-time provisions of the esa, noted, “The development of exemptions seems to have occurred without detailed analysis of the reasons given for requesting them.”72 Kinley identifies the major rationales for farm worker exceptionalism: variability of the weather, perishability of products, difficulty of recording hours of work on farms, and the inability of farmers to meet the costs that would result.73 Of these four rationales, the first two do not justify the overtime exemption and the third really does not seem to justify anything at all. That leaves the issue of cost as the sole rationale for exempting farm workers from overtime pay. Kinley’s focus, however, is much more on hours-of-work regulations than overtime entitlements and so does not subject this rationale to much scrutiny other than to accept that farmers face a price/cost squeeze.74

The agricultural exemption from hours of work and overtime provisions was also considered by Michael Thompson in his 1994 review of British Columbia’s minimum-standards regime. Like Kinley, he notes that the rationale for the exemptions is not given but points to the fact that much agricultural production is seasonal. Thompson links seasonality to the overtime exemption by arguing that overtime premiums encourage employers to hire more labour. However, he points out that farmers already experience serious difficulties hiring sufficient numbers of seasonal workers and that “the Commission is convinced that workers expect to work extra hours during the busy season to increase their incomes.”75 As a result, he supports continuation of the agricultural worker exemption, subject only to the imposition of an upper limit of 10 hours a day and 60 hours a week.

The farm worker exemption from overtime therefore seems to rest entirely on an argument about the economics of farming in Ontario. On the one hand, to the extent that Ontarians adopt a cheap food policy, it is being borne on the backs of agricultural workers who may be asked not only to work exceptionally long hours but to do so at low wages and without entitlement to premium pay for those excess hours. On the other hand, to the extent the justification is that we have no choice because of competitive pressure from even lower-cost, less regulated American and now Mexican producers, or producers from the Global South, the consequence is that agricultural workers are again paying the cost of free trade policies. In either event, defending the overtime exemption on the basis of these policies seems particularly problematic when the result is to further disadvantage and make more vulnerable a group of workers who already suffer disadvantage in the labour market because of their social location and immigration status. Thompson’s argument that the only rationale for overtime premiums is that it discourages long hours overlooks the additional rationale that workers who are subject to long hours of work are entitled to be paid at higher rates because of the burden it places on them physically, mentally, and socially. The fact that workers may expect or desire to work long hours to increase their incomes, especially when employed on a seasonal basis, may provide some justification for permitting longer hours, but it does not explain why those workers should be deprived of premium pay. While it may be true that agricultural workers do not expect premium pay for overtime hours, they may have been conditioned not to expect it by the very exemption that their diminished expectation supposedly justifies.

Agricultural employees comprise 10.2 per cent of all employees who work overtime that may not be fully remunerated.76 On average, agricultural workers report longer weekly hours of overtime work than those in other industries, working an average of 12.2 hours a week of overtime that may not be fully remunerated, in comparison to less than 8 hours a week for workers in other industries. It is clear that the doctrine of farm worker exceptionalism contributes to a labour environment in which overtime work has become an expected part of the job. The relation of the agricultural overtime exemption to the economics of farming in Ontario is quite apparent when the total cost of the overtime pay exemptions is assessed: across all agricultural workers, the exemption from overtime pay provisions of the esa results in a potential loss of almost a million dollars (over $990,000) in unpaid overtime premiums each week. The price of food in Ontario is effectively being unwillingly subsidized by these workers who labour long hours in precarious employment without the same remuneration paid to other Ontarians.

Managerial Exemptions

In Ontario, the overtime exemption for managers can be traced to early legislation governing hours of work and eating periods. The 1944 hwvpa exempted individuals in management positions. That exemption, however, was narrowly defined, applying to persons whose duties “are entirely of a supervisory, managerial or confidential character and do not include any work or duty customarily performed by an employee.”77 The managerial exemption – but not the exemption of persons employed in a confidential labour relations capacity78 – was incorporated into the esa in part by statute (hours of work, s. 7(2)) and in part by regulation (overtime, O. Reg 366/68 (1 Jan. 1969)). In each case, the scope of the exemption was worded a bit less stringently than in the hwvpa (“employee whose only work is supervisory or managerial”), but the gist was the same.

In applying the managerial exemptions, employment standards officers (esos) and Ontario Labour Relations Board (olrb) officials focused on the work an individual performs rather than the terms of their employment contract, job description, or title. They consider evidence of the capacity to make management decisions, supervise others, hire and fire others, and conduct performance reviews, among other tasks. Additional considerations are the frequency of and time spent performing non-managerial activities. Despite the word “only,” a number of olrb decisions have interpreted this regulation to allow an individual manager to engage in non-managerial activities and still be considered a manager exempt from overtime pay.79

This exemption was reworded in 2001, stipulating that overtime exemptions apply to individuals “whose work is supervisory or managerial in character and who may perform non-supervisory or non-managerial tasks on an irregular or exceptional basis.”80 According to the esa policy and interpretation manual, the wording change aimed “to clarify that the managerial exemptions can apply even if the individual is not exclusively performing managerial or supervisory work.”81 In applying the exemption, the olrb first determines whether the work was managerial or supervisory in character, focusing on the characteristics noted previously. If it is determined that the character of the work was managerial, the olrb then determines whether non-managerial tasks were performed on an irregular or exceptional basis, and the outcome often hinges on the interpretation and application of these terms. One approach is to define these terms narrowly. According to the ruling of Tri Roc Electric Ltd. v Butler, “the clear implication is that the regular performance of non-managerial duties in the ordinary course of an employee’s work renders the exemption inapplicable. Such approach is consistent with the well-accepted principle of statutory construction holding that limiting or exempting provisions in remedial legislation are to be narrowly construed.”82 However, other cases take a less restrictive view. For example, in Glendale Golf and Country Club Limited v Sanago the board held that notwithstanding that an executive chef performed non-managerial work regularly because the kitchen was often understaffed, the exemption still applied because the performance of this work was exceptional.83 The case also interpreted and applied an obscure subsection of the esa’s overtime provision stating that when an employee performs both exempt and non-exempt work in a week, the employee is entitled to overtime for hours in excess of 44 if the exempt work constitutes less than half their working time.84 Thus, in Sanago the board found that the executive chief was entitled to overtime in those weeks where the exceptional performance of non-managerial work constituted more than half his hours worked.

Despite the long history of the managerial exemption, there has been very little discussion of its justification, as Kinley discovered in his 1987 investigation of exemptions.85 However, in constructing post hoc rationales Kinley pointed to the following, which are arguably applicable to the managerial exemption: “strong bargaining position of the exempted worker based on skill, high level of responsibility, and/or organization; maintenance of independence and status of managerial, professional, and skilled groups; the high cost of observing hours standards.”86 Thompson’s 1994 review of the es in British Columbia briefly stated that the rationale for the managerial exemption was that “they have some power to control their own hours of work.” He also noted that “structural changes in the economy have blurred the distinction between managers and their subordinates somewhat. In some organizations, managers are asked to do non-managerial work at times when their staff would be entitled to premium pay.” He recommended retaining the managerial exclusion but applying it only when individuals are acting in a managerial capacity.87 Over one-third (36.1 per cent) of Ontario employees who work overtime that may not be fully remunerated perceive their job to be managerial. The overtime pay exemption for managers is responsible for the largest total loss to workers in terms of overtime remuneration: $5 million a week, collectively. While some of these managers are highly compensated, others earn low wages. For example, among managers in full-service restaurants and limited-service eating places – who comprise 4.0 per cent of all managers in Ontario (the second-largest group, after those in computer systems design) – 17.1 per cent earn low wages.88

We are inclined to accept the general rationale for the exclusion; however, like Thompson we are concerned about the erosion of its boundaries and the expansion of its reach, which gives rise to the problem of classification or misclassification. As we have seen, the legal definition of the managerial exclusion has been broadened and the olrb is not consistent in interpreting its limits narrowly. This helps to create an atmosphere conducive to misclassification of employees as managers as an evasion strategy for employers in the province. The Ontario Ministry of Labour’s 2013 retail enforcement blitz emphasized managerial misclassification as a priority for inspectors. The phenomenon is widespread. For example, in the United States, the extent of managerial misclassification is underscored by two nationwide surveys of nursing homes conducted by the US Department of Labor in the late 1990s. These surveys established a compliance level of 70 per cent in 1997 and only 40 per cent in 1999, and cited overtime violations related to misapplied managerial and professional exemptions as key factors in such low compliance rates.89

Trucking, Trade, and Transport Special Provisions

Trucking, trade, and transport make up another occupational group with differential rules regarding overtime pay. Work in this industry has been covered by working-time regulations in the form of maximum weekly hours of work to protect the safety of not only drivers but also the general public, as long hours of work may impair a driver’s ability to operate a vehicle. Yet the industry is also subject to cyclical and seasonal variation, as well as intense competitive pressures. These factors, in conjunction with industry lobbying, have prompted the development of special provisions in overtime regulation, which allow for greater flexibility in the organization of working time for drivers and increase the weekly hours of work compensated without an overtime premium. In the 1980s, the tfhwo undertook a special examination of the trucking and transportation industry, given the complex nature of the industry and the proliferation of special rules governing its working conditions.90 We focus on the industry here for similar reasons.

With regard to coverage of trucking and transport occupations, legislative jurisdiction over employment conditions has been characterized by special provisions as well as a long-standing source of uncertainty in terms of the interpretation and enforcement of overtime regulations.91 The standards of Ontario’s esa apply if an employee’s work is to be performed in Ontario or if it is to be performed “outside Ontario but … is a continuation of work performed in Ontario.”92 Because of the cross-border nature of the trucking industry, there is potential overlap with coverage under the Canada Labour Code (clc), which sets minimum standards for workers in federally regulated industries, including those engaged in work of an interprovincial nature. For transport workers covered by the clc, the esa does not apply. Additionally, those who work as owner-operators are not covered by the esa.

As of 2016, there were 205,157 people employed in transportation industries in Ontario, with approximately 31 per cent of these employees either union members or covered by a collective agreement. Of the non-unionized employees in transportation industries, approximately 49 per cent were employed in truck transportation and are therefore impacted by the esa overtime provisions discussed below.

Under the esa, two categories of employees in trucking, trade, and transportation industries fall under special rules for overtime pay: highway transport truck drivers, defined as those “employed to drive trucks used in most ‘for hire’ trucking businesses, other than local cartage businesses”; and local cartage drivers and driver’s helpers, defined as those “employed as drivers of vehicles in a business that carries goods for hire within a municipality (or not more than five kilometres beyond a municipality’s borders)” and those employed as their helpers.93 When the esa was originally enacted, these workers were covered under the industry permits that established special provisions for excess hours and through regulations that increased the threshold for the overtime premium. Initially, the overtime premium was payable after 60 hours in the highway transport industry and after 55 hours in the local cartage industry (later reduced to 50 hours).94 With the removal of the industry permits system through the esa reforms of 2000, both groups of workers received special provisions governing their overtime hours that replicated these conditions. Under the esa 2000, highway transport truck drivers are entitled to overtime pay for hours in excess of 60 in a workweek, while local drivers and their helpers are entitled to overtime pay for hours in excess of 50 in a workweek.95

The special provisions for overtime pay – which allow for standard rates of pay for hours of work beyond the normal overtime threshold – are long-standing, yet we must set them in the context of recent processes of broader regulatory reform in the North American trucking industry to fully grasp their implications. In trucking, regulatory reform includes the rewriting of industry-specific regulations to enhance market/competitive forces,96 which coincided with alterations to more general laws that govern employment relations (affecting union organizing, collective bargaining, wage rates, and other minimum employment standards) and the ineffective enforcement of those laws, as well as the implementation of the (former) North American Free Trade Agreement to reduce the regulation of cross-border trade.97 These processes – which, for the trucking industry, date to the late 1970s – have heightened competitive pressures in price setting and furthered industry restructuring, thereby intensifying problems of low wages, long hours of work, and unsafe working conditions. Experiencing a decline in mileage rates, drivers are compelled to drive faster and work longer hours to compensate for income shortfalls. These tendencies have been exacerbated through the growth of owner-operators in the industry, which itself has an effect of heightening competition between trucking companies and among drivers themselves in much the same ways as the presence of subcontracting does in other industries.98

There are several rationales for the special treatment of truckers under the esa working-time provisions generally, and the overtime pay provisions specifically, all of which relate to the nature and organization of the trucking industry.99 First, the diverse nature of the industry, which includes short- and long-distance carriers as well as trucking companies and independent owner-operators, has given rise to multiple working-time regulations that reflect this variation, with different regulations for hours of work and overtime for these different groups. Second, the industry is often subject to environmental constraints, including weather and the seasonal nature of some goods, creating the general need for greater flexibility in working time and, in particular, long hours of work. Customer practices in terms of just-in-time inventory systems also factor into the pressures for longer working hours, as does increased competition generated by trucking industry deregulation. The avoidance of overtime pay is also justified in terms of the expectation and assumption that long hours are a necessary part of the work, particularly in highway transport. Additionally, employers in the industry have voiced concerns that excessive working-time regulation (i.e. through limits to weekly hours and/or a lower threshold for overtime pay) could hamper competitiveness.

Together, truckers comprise 18.8 per cent of employees who work overtime that may not be fully remunerated. Truckers who worked overtime in the reference week worked an average of 5.4 hours that may not be fully paid.100 Of these truckers, 17.0 per cent worked less than 6 additional hours, 35.3 per cent worked between 6 and 12 additional hours, and 47.7 per cent worked 12 or more additional hours in the reference week. Collectively, the overtime pay exemption for truckers potentially costs truck drivers over $900,000 each week and likely much more.

Given the intersection between decent working conditions (which include the right to overtime pay and limits on weekly hours of work) and public safety created through trucking, the rationales for the special rules on overtime pay are concerning. As a lower overtime threshold could have the effect of reducing excess hours, changing the special provisions could not only improve working conditions for drivers but also contribute to public safety. Lowering the overtime pay threshold could also counter some of the aforementioned trends in trucking work, specifically, the tendency of declining wages that contributes to excess hours, resulting from industry restructuring. It is important to note, however, that a change of this nature would not address the conditions of independent owner-operators, who are not entitled to overtime pay due to their independent contractor status. A more comprehensive strategy to regulate the working conditions of owner-operators would be required, such as that proposed by the Federal Labour Standards Review, which recommended using sectoral conferences to develop special regulations for “autonomous” workers such as owner-operators in trucking.101

Conclusion

This article began by raising the prospect of an es coverage crisis involving an increasing selectivity in coverage of employment law.102 Selective coverage, however, is not new. Through an investigation of the history of exemptions in Ontario’s minimum-standards laws, we revealed long-standing tendencies for certain groups of workers to be fully or partially exempt from minimum standards or to be subject to special rules that effectively create differential standards that are lower than those experienced by the majority of workers. These exemptions and special rules have accommodated employer demands to be able to continue to organize work in ways that maximize profit. Not surprisingly, we found that this tendency shaped the esa, in that the Ontario government responded to intense demands for special treatment from employers in particular industries.

In light of the broader tendency toward precarious employment, these exemptions can clearly be seen to intensify the overall erosion of es by subjecting workers to market forces with little or no regulatory protection. Rather than a uniform floor of minimum workplace rights, through exemptions and special rules, es are thus better conceptualized as a patchwork of rights applied unevenly across the labour market. In addition to this general concern, through a detailed focus on the overtime pay exemption in terms of its overall application, we were able to quantify the impact of this differential treatment. Specifically, approximately 1 of every 40 non-unionized Ontario employees report working overtime that may not be fully remunerated because of the esa’s overtime pay exemptions, totalling over 730,000 hours a week that workers may not be fully paid for, for a sum of potentially over $11 million weekly in lost wages. Moreover, given the negative health effects of excessive working hours, the overtime exemption and special rules for certain occupations, such as farm workers and truck drivers, may pose health risks to both the affected workers and the general public. Though the system of exemptions is and has been justified in terms of the need to attend to the special characteristics of specific sectors, industries, and occupations, we contend that in light of the connections between exemptions and precariousness in the labour market, this approach to es regulation needs to be rethought.

In recent years, as the organizing of non-unionized workers through organizations such as the Workers’ Action Centre has increased pressure on the Ontario government to improve minimum standards, the government has taken legislative measures to extend the scope of es coverage to certain, traditionally poorly protected groups, including temporary foreign workers, live-in caregivers, and temporary agency employees. In 2015, as a result of the growing attention placed on precarious employment, the Ontario government appointed the Changing Workplaces Review to consider how to respond to the growth of precarious employment. The special advisers recommended legislative changes and a review of esa exemptions and special rules designed to augment employment standards and their enforcement. In 2017, the government implemented many of the recommendations in the Fair Workplaces, Better Jobs Act and commenced a review of special rules and exemptions.103 However, reflecting the historical tensions we identified at the outset, in 2018 the recently elected Conservative government promptly repealed many of the changes made by the 2017 legislation and ended the review of exemptions and special rules.104 As a result, the narrowing of exemptions has been minimal.

The findings of this article, in terms of both the material impact of the overtime exemption specifically and the broader connections between exemptions and the spread of precarious employment, support the impetus for a more universalist approach to es regulation by eliminating selective treatment that undermines workplace protection.105 Specifically, reversing the “coverage crisis” requires an approach to es regulation that reasserts the principles that initially gave rise to such standards – these being the need for labour-market protections premised upon universality, fairness, and social minimums. This reversal need not take the form of identical standards for all workers. In fact, ensuring a fair social minimum through expanding es coverage could also be accompanied by additional regulations and resources targeted at groups of precariously employed workers in ways that address the circumstances that heighten their precariousness, such as those discussed above in agricultural, managerial, and trucking occupations (though a full discussion of such a strategy is beyond the scope of this article).106 Nevertheless, we contend that revising es regulation in a manner that broadens coverage, and eliminates special rules that contribute to an erosion of social minimums, would constitute a meaningful step toward countering precariousness in industrialized labour markets.

The research for this article was funded by a Partnership Grant titled Closing the Employment Standards Enforcement Gap: Improving Protections for People in Precarious Jobs. We are grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for its support and to members of the larger research team for their comments on an earlier version of the article.

1. Leah Vosko, “Precarious Employment: Towards an Improved Understanding of Labour Market Insecurity,” in Leah Vosko, ed., Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 3.

2. Guy Davidov, “Setting Labour Law’s Coverage: Between Universalism and Selectivity,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 34, 3 (2014): 543.

3. Bob Barnetson, “The Regulatory Exclusion of Agricultural Workers in Alberta,” Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work and Society 14 (Autumn 2009): 50; Barnetson, “No Right to Be Safe: Justifying the Exclusion of Alberta Farm Workers from Health and Safety Legislation,” Socialist Studies 8, 2 (2012): 134; Eric Tucker, “Will the Vicious Circle of Precariousness Be Unbroken? The Exclusion of Ontario Farm Workers from the Occupational Health and Safety Act,” in Vosko, ed., Precarious Employment, 3; Tucker, “Farm Worker Exceptionalism: Past, Present, and the post-Fraser Future,” in Fay Faraday, Judy Fudge & Eric Tucker, eds., Constitutional Labour Rights in Canada: Farm Workers and the Fraser Case (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2012), 30; Judy Fudge & Fiona MacPhail, “The Temporary Foreign Worker Program in Canada: Low-Skilled Workers as an Extreme Form of Flexible Labor,” Comparative Labour Law & Policy Journal 31(2009): 5; Rachel Li Wai Suen, “You Sure Know How to Pick ’Em: Human Rights and Migrant Farm Workers in Canada,” Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 15 (2001): 199.

4. Employment Standards Act (hereafter esa), 2000, so 2000, c 41.

5. Mark Thomas, Regulating Flexibility: The Political Economy of Employment Standards (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 87.

6. Leah Vosko, Andrea Noack & Mark Thomas, How Far Does the Employment Standards Act, 2000 Extend and What Are the Gaps in Coverage? An Empirical Analysis of Archival and Statistical Data (Toronto: Ministry of Labour, 2016).

7. Portions of the analysis presented in this article were conducted at the Toronto Region Statistics Canada Research Data Centre (rdc), which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (crdcn). The services and activities provided by the Toronto rdc are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of the sshrc, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (cihr), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (cfi), Statistics Canada, and the University of Toronto. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the crdcn or of its partners. Data analyses for this project were completed by Alix Holtby, Dr. Alice Hoe, and Dr. Mark Easton.

8. Leah Vosko & Mark Thomas, “Confronting the Employment Standards Enforcement Gap: Exploring the Potential for Union Engagement with Employment Law in Ontario, Canada,” Journal of Industrial Relations 56, 5 (2014): 631.

9. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “The Labour Standards Act, Background Memorandum,” 25 January 1968, rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1407.3, box 47, Archives of Ontario, Toronto (hereafter ao). A comprehensive discussion of the various factors that influenced the government in the development of early minimum standards legislation in Ontario is beyond the scope of this article. For further discussion, see Mark Thomas, “Setting the Minimum: Ontario’s Employment Standards in the Postwar Years, 1944–1968,” Labour/Le Travail 54 (Fall 2004): 49–82.

10. Ontario Task Force on Hours of Work and Overtime (tfhwo), Working Times: The Report of the Ontario Task Force on Hours of Work and Overtime, report submitted to the Ministry of Labour (Toronto 1987), 26.

11. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility, 66.

12. The Lord’s Day Act, spc 1845, c 45, s 1.

13. Lord’s Day Act, 1906, sc 1906, c 27, s 3(m); Sharon Patricia Meen, “The Battle for the Sabbath: The Sabbatarian Lobby in Canada, 1890–1912,” PhD. diss., University of British Columbia, 1979. The law and the exemption remained in force until the legislation was struck down as an unconstitutional infringement of the right to freedom of conscience and religion under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. See R v Big M Drug Mart Ltd., [1985] 1 scr 295.

14. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility. On the Nine-Hour Movement, see John Battye, “The Nine Hour Pioneers: The Genesis of the Canadian Labour Movement,” Labour/Le Travail 4 (1979): 25–56. On the role of middle-class social reformers, see Eric Tucker, “Making the Workplace ‘Safe’ in Capitalism: The Enforcement of Factory Legislation in Nineteenth-Century Ontario,” Labour/Le Travail 21 (1988): 45–85.

15. Hours of Work and Vacations with Pay Act, so 1944, c 26.

16. On the wartime labour struggles that led up to the establishment of postwar labour relations legislation, see Bryan Palmer, Working Class Experience: Rethinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800–1991 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992), 278–284. See also Leo Panitch & Donald Swartz, From Consent to Coercion: The Assault on Trade Union Freedoms (Toronto: Garamond, 2003). On the gendered organization of the postwar labour and employment law regime, see Judy Fudge & Leah F. Vosko, “Gender, Segmentation and the Standard Employment Relationship in Canadian Labour Law, Legislation and Policy,” Economic and Industrial Democracy 22, 2 (2001): 271–310.

17. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

18. Davidov, “Setting Labour Law’s Coverage,” 543.

19. Labour Gazette (Sept. 1944), 1180–1181. For the controversy around the inclusion of the textile industry in the war industry exemption, see “The Textile Industry and the 48-Hour Week,” Toronto Daily Star, 19 August 1944, 6. The textile employers’ group, the Primary Textile Institute, petitioned the board to be included. The union representing textile workers was not consulted.

20. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

21. Department of Labour, “Annual Conventions of the Ontario and Quebec Federation of Labour,” Labour Gazette 68 (Ottawa, 1968), 78; Thomas, “Setting the Minimum,” 49; Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

22. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility, 25.

23. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

24. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Memorandum Re: Employment Standards Act,” n.d. [1968], rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1407.2, box 47, ao; T. M. Eberlee, deputy minister, to Hon. H. L. Rowntree, minister of labour, memorandum, 21 October 1966, rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1156, box 36, ao.

25. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility, 66.

26. Employment Standards Act, so 1968, c 35.

27. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Notes for an Address by the Hon. Dalton Bales, Q.C., Minister of Labour for Ontario, during 2nd Reading of: The Employment Standards Act, 1968,” 31 May 1968, rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1407.2, box 47, ao.

28. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

29. R. M. Warren, executive director, Manpower Services, memorandum, 3 February 1969, rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1533.1, box 54, ao.

30. Canada, Department of Labour, “Recent Regulations under Provincial Legislation,” Labour Gazette 69 (Ottawa, 1969), 108–110; Canada, Department of Labour, “Labour Legislation in 1968–69,” Labour Gazette 69 (Ottawa, 1969): 736–745. Donald Dewees notes that it is difficult to establish a rationale or purpose for each working time exemption because “the true motive for each of the various exemptions is not clearly identified in the Act nor in the available documentation.” Dewees, Special Treatment under Ontario Hours of Work and Overtime Legislation: General Issues, report prepared for the Ontario tfhwo (Toronto 1987).

31. O Reg 366/68, s. 5.

32. While exemptions were made for seasonal employees in fruit and vegetable processing, there was reluctance to grant exemptions to all seasonal employees, because “it is often those employees who have little or no other choice but to work in these seasonal industries who must need the protection of our legislation.” Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Memorandum, Re: Representation from the Ontario Ski Area Operators Association,” 28 April 1969, rg7-1, file 7-1-0-1532.3, box 54, ao.

33. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Employment Standards Branch, Working Conditions and Analysis Section, Reduction of Working Time and Job Creation, 1984, rg7-168, Policy Subject Files, ao.

34. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

35. John Kinley, Evolution of Legislated Standards on Hours of Work in Ontario, a report prepared for the Ontario tfhwo (Toronto 1987).

36. Ontario Federation of Labour, Guide to the Ontario Ministry of Labour’s Changes to the Employment Standards Act (Bill 147) (Toronto: Ontario Federation of Labour, 2001).

37. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Memorandum, Re: Ontario Federation of Labour,” 6 April 1976, rg7-78, ao.

38. Dewees, Special Treatment; Kinley, Evolution of Legislated Standards.

39. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Research Branch, “Some Questions Concerning the Purpose of Employment Standards Legislation and Government Activities Intended to Improve Work Conditions,” 15 December 1976, 4–5, rg7-78, ao; Dewees, Special Treatment.

40. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Memorandum, Ontario Swimming Pool Association,” 20 June 1975, rg7-78, ao; Ontario, Ministry of Labour, letter from Ready Mixed Concrete Association of Ontario, 22 October 1974, rg7-78, ao; Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Memorandum, Re: Ontario Milk Distributors Association,” 8 January 1969, rg7-78, ao; Ontario, Ministry of Labour, “Further Presentation of the Ontario Hotel and Motel Association to the Industry and Labour Board for Ontario,” 16 May 1967, rg7-78, ao.

41. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility.

42. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Program, Statistics, and Current Legislation, 1982, 16, rg7-78, ao.

43. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Research Branch, “Legislated Hours of Work and Premium Pay Provisions,” March 1977, rg7-78, ao; Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Labour Services Division, Staff Branch, “Employment Standards – Overtime/Excess Hour Permits,” 6 April 1976, rg7-78, ao.

44. The permit system was also highly utilized by unionized employers. Ontario tfhwo, Working Times.

45. Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Research Branch, “Legislated Hours of Work.”

46. Dewees, Special Treatment, 15.

47. Ontario tfhwo, Working Times.

48. esa, 2000, so 2000, c 41.

49. Because this article focuses on exemptions and special rules, the provisions regarding “employee consent” for excess hours and overtime averaging are beyond its scope. See Mark Thomas, “Toyotaism Meets the 60-Hour Work Week: Coercion, Consent, and the Regulation of Working Time,” Studies in Political Economy 80, 1 (2007): 105–128.

50. Employment Standards Amendment Act (Hours of Work and Other Matters), so 2004, c 21.

51. Law Commission of Ontario, Vulnerable Workers and Precarious Work: Final Report (Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario, 2012), 42.

52. A detailed and comprehensive discussion and analysis of esa exemptions is contained in Vosko, Noack & Thomas, Employment Standards Act, 2000.

53. According to the Special Rule tool, “This special rule concerning overtime pay applies only if the employee is employed by the owner or operator of the hotel, motel, tourist resort, restaurant or tavern.”

54. Law Commission of Ontario, Vulnerable Workers.

55. Vosko, Noack & Thomas, Employment Standards Act, 2000.

56. Judy Fudge, “Control over Working Time and Work-Life Balance: A Detailed Analysis of the Canadian Labour Code, Part iii,” Federal Labour Standards Review Commission, February 2006.

57. The analysis excludes non-unionized workers who are covered by a collective agreement. This is because the employment relationship of these workers is regulated by the collective agreement that covers them, and they are not solely reliant on the social minimums established by the esa. The analysis does not include supervisors who are not coded under managers as exempt, meaning the results likely undercapture the scope of the overtime problem.

58. Special Rules and Exemptions tool, accessed at https://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/es/tools/.

The population of interest is Ontario employees aged 16 to 69 who fall under the jurisdiction of the province’s esa, based on the industry and occupation of their main job. Residents of institutions and persons living on reserve are excluded from the lfs sample. This analysis is subject to some notable limitations in terms of what types of workers can be identified, since there is limited congruence between the job classifications used by the Ontario Ministry of Labour and the internationally comparable classifications used by Statistics Canada. In some cases, it was difficult to match the occupations specified in the esa regulations with the occupations classified in the noc-S. Some occupations with esa exemptions, such as swimming pool installers, are simply unidentifiable in the noc-S and naics classifications. Other occupational exemptions were too specific to be captured by the classifications – for example, the esa includes exemptions for public accountants; however, the noc-S and naics do not distinguish between public accountants and other accountants. As a general principle, we erred on the side of inclusion; that is, if we were not confident that members of an industry/occupation group were excluded from the overtime pay provisions, we assumed that they were. Thus, these results likely underestimate the scope and effect of overtime pay exemptions.

59. All calculations regarding hours worked are based on reported paid hours. Some workers worked additional unpaid hours – these hours are not included in calculations.

60. For one industry, construction, the overtime pay provision does not come into effect until after 55 hours of work. These employees could not be definitively identified in the data set. For all other partially exempt industry groups that could be identified in the data, overtime pay provisions come into effect after 50 hours of work.

61. The data do not indicate whether employees received premium pay for the hours beyond 44 that they worked. The analysis of lost weekly wages relies on the assumption that premium pay for overtime was not paid if it was not required by law.

62. For employees fully exempt from overtime pay standards, lost wages are calculated as the number of weekly hours worked above 44, multiplied by 0.5 their usual hourly wage, plus 4 per cent vacation pay for employees who are so entitled. For employees partially exempt from overtime pay standards, lost wages are calculated as the number of weekly hours worked above 44 up to the occupationally specific threshold for overtime pay, multiplied by 0.5 their usual hourly wage, plus 4 per cent vacation pay for employees who are so entitled.

63. See Greg Schell, Farmworker Exceptionalism under the Law, in Charles D. Thompson Jr. & Melinda F. Wiggins, eds., The Human Cost of Food: Farmworkers’ Lives, Labor, and Advocacy (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2002), 139.

64. Farm worker exemptions apply to all harvesters and farm employees regardless of residency status, including temporary foreign workers. See Leah Vosko, Eric Tucker & Rebecca Casey, “Enforcing Employment Standards for Migrant Agricultural Workers in Ontario, Canada: Exposing Underexplored Layers of Vulnerability,” International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 35, 2 (2019): 227–254. Our focus here is on their exemption from hours of work and overtime laws, but it is worth recalling that in Ontario farm workers were exempted from occupational health and safety regulations until 2006 and from workers’ compensation until 1965; further, they remain exempted from the province’s general collective bargaining statute and instead have been covered by the Agricultural Employees Protection Act since 2002 – an act so ineffective that no collective bargaining relationship has ever been established under its auspices. These exemptions are dealt with at great length in Tucker, “Vicious Circle of Precariousness”; Tucker, “Farm Worker Exceptionalism.”

65. Hours of Work and Vacations with Pay Act, so 1944, c 26.

66. Davidov, “Setting Labour Law’s Coverage,” 1180–1181.

67. “Another Pledge Kept,” Globe and Mail, 17 October 1945, 16; O Reg 92/45.

68. O Reg 102/52.

69. Thomas, Regulating Flexibility; O Reg 366/68, s 1, 4 & 5; O Reg 374/68.

70. O Reg 285/01.

71. One of the only policymakers to address farm worker exceptionalism was William Meredith, the chief justice of Ontario, who wrote the report that was the basis for Ontario’s first no-fault workers’ compensation scheme. Meredith stated that while in principle farm workers should be covered, he doubted whether public opinion would support their inclusion and so did not try to have them covered. See Tucker, “Vicious Circle of Precariousness.”

72. Kinley, Evolution of Legislated Standards, 49.

73. Kinley, 49.

74. Kinley, 52–57, 69, 72.

75. Michael Thompson, Rights and Responsibilities in a Changing Workplace: A Review of Employment Standards in British Columbia (Victoria: Ministry of Skills, Training and Labour, 1994).

76. The proportion of agricultural workers surveyed in the lfs is likely an underestimation in relation to overall overtime work. The survey sampling frame only includes temporary foreign workers if they identify their Canadian dwelling as their usual place of residence. Temporary foreign workers comprise a very small proportion of lfs respondents. The category of agricultural workers also includes some respondents who provide support services for agricultural work.

77. Davidov, “Setting Labour Law’s Coverage.”

78. It is interesting to speculate as to whether the exclusion in the hwvpa was inspired by the managerial and confidential labour relations exclusion in Canada’s Wartime Labour Relations Regulation (PC 1003, s 2(1)(f)), promulgated on 17 February 1944. The hwvpa was introduced shortly after, on 3 April. The heated debate in the United States over whether management should be excluded from collective bargaining is explored in detail in Jean-Christian Vinel, The Employee: A Political History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

79. See Singer v McMaster University, 2001 Canlii 16376 (on lrb). See also Kennedy v William C. Cavell Enterprises Ltd., [1987] OJ No 1050; Ideal Parking Inc, [1999] osead No 58.

80. O Reg 285/01 s 8(b), emphasis added.

81. Ontario, Employment Practices Branch, Employment Standards Act, 2000: Policy and Interpretation Manual (Toronto: Carswell, 2003), 31-21.

82. Tri Roc Electric Ltd. v Butler, 2003 Canlii 1390 (on lrb). See also Baarda v Plywood and Trim Co. Ltd., 2004 Canlii 16978 (on lrb).

83. Glendale Golf and Country Club Limited v Sanago, 2010 Canlii 4265 (on lrb).

84. esa, 2000, so 2000, c 41, s 22(9).

85. Kinley, Evolution of Legislated Standards.

86. Kinley, Evolution of Legislated Standards, 22.

87. Thompson, Rights and Responsibilities, 98.

88. Following the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (oecd), low wages are calculated as less than two-thirds of the median wages of full-time employees in Ontario.

89. United States Department of Labor, Employment Standards Administration, Wage and Hour Division, 1999–2000 Report on Initiatives (Washington, DC, 2001), 20.

90. Fred Lazar, Trucking Industry and the Worktime Provisions of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act, report prepared for the Ontario tfhwo (Toronto 1987).

91. Lazar.

92. esa, 2000, so 2000, c 41, s 3(1).

93. In addition, taxi cab drivers are not entitled to overtime pay. O Reg 285/01, s 8(j).

94. Canada, Department of Labour, “Labour Legislation in 1968–69.”

95. O Reg 285/01, s 18; O Reg 285/01, s 17.

96. This included the passage of the Motor Carrier Act in the United States in 1980 and the Motor Vehicle Transport Act in Canada in 1987. See Daniel Madar, Heavy Traffic: Deregulation, Trade, and Transformation in North American Trucking (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000).

97. Michael Belzer, Sweatshops on Wheels: Winners and Losers in Trucking Deregulation (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Madar, Heavy Traffic.

98. Harry W. Arthurs, Fairness at Work: Federal Labour Standards for the 21st Century (Ottawa: Federal Labour Standards Review, 2006).

99. Dewees, Special Treatment.