Labour / Le Travail

Issue 84 (2019)

article

Building Union Muscle: The GoodLife Fitness Organizing and First-Contract Campaign

On 6 June 2016, personal trainers at 42 GoodLife Fitness locations across Toronto, Canada, made history by voting 181 to 116 in favour of unionization. They were reported to be the first group of personal trainers in North America to win union certification and a first contract.1 This historic victory was tempered in part by the fact that fitness instructors working at GoodLife locations across the Greater Toronto Area [gta] overwhelmingly rejected unionization in a separate vote count. Within six months, GoodLife personal trainers in two other Ontario cities, Ajax and Peterborough, also joined Workers United and, in December 2017, trainers ratified their very first union contract. This case study assesses the strategy and tactics used in the organizing and first-contract campaigns.

The union’s partial certification victory and its success at securing a first contract for personal trainers at GoodLife Fitness were historic, owing to the union’s comprehensive campaign approach to both organizing and collective bargaining. This strategic approach recognizes the central importance of gaining a wide-ranging understanding of the company and sector under target. With a specific focus on better understanding the power dynamics in a firm, and which vulnerabilities are most effectively exploited, comprehensive strategic campaigns are designed to creatively apply pressure on employers in a multitude of ways in order to defend or advance a union’s strategic objectives.2 The campaigns targeting GoodLife embraced unconventional tactics that drew on a variety of power sources outside of the traditional structural-economic modes most familiar to unions, namely, the withdrawal of labour or work-to-rule campaigns. Instead, the union pursued a combination of coordinated strategies based on institutional, associational, and symbolic power.3

In a union context, “power” refers to the measure of workers’ collective ability to bring about change and to advance their own interests. Drawing on Tom Juravich’s framework for the development of union strategic campaigns, institutional power is derived from the rights and other provisions embedded in labour and employment laws. Building institutional power often entails working with politicians on pro-union public-policy reforms.4 Associational power, on the other hand, is based on the idea that coalitions and partnerships with like-minded organizations or movements can help to build influence and reduce isolation, thus augmenting a union’s power to externally effect change. Finally, symbolic power refers to the potential of unions to use moral suasion, often through social justice frames, to shape public opinion and leverage it to workers’ benefit. Combined, these sources of power guided Workers United’s strategic decisions relating to the scope of the organizing effort, the use of corporate campaign tactics, the use of social media as a tool to recruit and organize workers, and the forging of alliances with broader political movements seeking legislative improvements to workers’ rights. The union’s GoodLife campaign thus provides some interesting insights about how to build union muscle in an industry that is virtually union-free.

In order to make better sense of the union’s historic breakthroughs, it is necessary to understand the context in which the campaigns unfolded. To that end, this article begins with background information on the gym and fitness club industry, Workers United, and GoodLife Fitness. The article then situates the Workers United campaign in the broader context of previous research on union organizing in the private service sector economy. With the help of media reports, key informants,5 and primary documents associated with the union drive, the article then describes the union campaigns and management’s response to them. Interviews with union officials and GoodLife workers were used to gather new information and to corroborate data gathered through primary documents and media reports. Interviews also served to produce a clearer, more detailed, and more nuanced analysis. The article concludes by providing a critical assessment of the union drive and first-contract fight and a discussion of the lessons the campaign provides for organizing workers in the precarious private service sector.

Gym and Fitness Club Work

Gym and fitness clubs are a $4.5 billion industry in Canada. Thanks in part to an aging population and the proliferation of public health campaigns, industry revenue grew at an annual rate of 6.8 per cent between 2014 and 2019.6 The number of workers in the industry is also growing. While demographic data on gym and fitness club workers is not available, one union official close to the GoodLife organizing campaign described the workforce in the gta as multiracial, with group fitness instructors skewing older (40+) and female, and personal trainers skewing younger and male.7 According to Statistics Canada, 50.5 per cent of the industry is made up of self-employed individuals and just under 80 per cent of all gym and fitness clubs in Canada have a staff of fewer than ten workers.8 In recent years, however, the industry has seen a shift toward large-scale establishments, like GoodLife, with larger, directly employed workforces made up of customer service representatives, group fitness instructors, personal trainers, and other staff positions.9 Whether contract-based or permanent, work in the gym and fitness club industry is largely precarious.

In an employment context, precarity refers to work that is unstable and insecure.10 In general, independent contract positions are considered to be more precarious than direct employment because the former are not entitled to statutory employment standards benefits or protections such as minimum wage, emergency leave, or paid vacations.11 Moreover, independent contractors in the gym and fitness club industry are solely responsible for recruiting and retaining clients and therefore assume all of the risk for the profitability of their work and business arrangements. However, there is little evidence that the growth of large-scale gyms and fitness clubs operating with employees rather than independent contractors has made work in the industry any less precarious. In fact, some interviewees with experience working in the industry as both employees and independent contractors argued that being employed at GoodLife made their lives more precarious as a result of the enforcement of non-compete clauses and the non-adherence to employment standards protections, especially as they related to overtime pay and minimum wage (issues that are revisited later in detail as part of this case study).12 Anecdotally, interviewees all expressed the view that the level of turnover was generally high in the gym and fitness club industry and even higher at GoodLife, where many trainers get their start before branching off on their own as independent contractors with their own personal client base.

Gym and fitness club revenue is derived primarily from membership fees and personal training services. Profitability is difficult to gauge given that GoodLife, the only major player in the industry, is privately owned and does not release financial data. However, a March 2019 ibisWorld Industry Report estimated that the industry-leading company grew its revenue at an annualized rate of 11.5 per cent to $834.7 million between 2014 and 2019.13

GoodLife, founded in 1979 in London, Ontario, by sole owner and ceo David Patchell-Evans, has grown into a global fitness industry powerhouse. The company is the fourth-largest fitness chain in the world, and by far the largest in Canada.14 GoodLife opened up new clubs at an annualized rate of 6.1 per cent between 2014 and 2018.15 The company has more than 400 facilities across Canada and had more than 1.5 million members as of March 2019. That is 1 out of every 25 Canadians. In Ontario, it operates 155 clubs. The company also owns a discount-priced gym chain, Fit4Less, which has over three dozen facilities in Ontario.16

While GoodLife has had incredible success with its business model, internal challenges as they relate to labour relations have been brewing for many years. Concerns about wage theft bubbled to the surface in 2011 when a group of fitness instructors filed a complaint with the Ontario Labour Relations Board (olrb) about GoodLife’s “45-minute hour” – the portion of the work hour that instructors were actually paid to lead classes in one-hour blocks. After an employee won his case at the board in 2012, GoodLife promptly amended the terms of its employment contracts to ensure that instructors would only be paid for the actual minutes they spent instructing.17 Essentially, the new company policy was that workers would only be paid for the time they spent leading the fitness class, leaving many GoodLife employees shaking their heads in disbelief. “You’d only get paid for 45, 50 or 55 minutes instead of an hour,” Workers United organizer Tanya Ferguson told now Magazine. “But when people come for a yoga class, for instance, they might have a question afterwards, and instructors are expected to stay and answer. You’d also arrive early so you could set up. The reality is that people were already working for more than an hour, but now they were getting paid less,” she added.18

More than 90 per cent of GoodLife fitness instructors work two to five hours a week. A large portion are “hobbyists” who lead one or two classes a week in exchange for token pay and a free club membership.19 The existence of this reserve pool of labour has made the work of experienced instructors who are trying to make a career in the industry far more precarious. In January 2016, Toronto Star reporter Sara Mojtehedzadeh wrote a piece on a Ministry of Labour inspection blitz involving numerous infractions under Ontario’s Employment Standards Act by GoodLife and other Toronto gyms. The fitness sector, she wrote, was becoming a new frontier of precarious work.20 Examples of the precarious nature of work at GoodLife abound.

In fact, the same employee who initiated the successful labour board complaint in 2011 was fired a few years later along with other instructors for violating the company’s legally dubious non-compete clause by leading exercise classes outside of GoodLife. “One thing GoodLife claims is that they have plenty of work for us, and we don’t need to work for other gyms,” the fired employee told the Globe and Mail. “But then they do the polar opposite by reducing our classes and pay, which forces us to work elsewhere. Then they fire us for doing it.”21

GoodLife’s policies were effectively trapping workers in precarious employment situations. Given the tremendous power imbalance at play, it should come as little surprise that some group fitness workers began to actively explore the possibility of unionization. After being turned down by one union, the workers turned to Workers United for help. “The whole idea of coming together, I think, has served society well in general,” explained one worker interviewed for this research. “For me, a union is just an extension of that.”22

Workers United is an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union (seiu) in Canada. Workers United represents roughly 10,000 workers across Canada and over 100,000 workers in the United States. It is a relatively small general union with membership concentrated in the garment and apparel industry; plastics, auto parts, and industrial manufacturing; distribution centres; and food service. The union – a product of the failed merger of the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (unite) and the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (here) in 2009 – has a track record of organizing in very difficult sectors, including retail and fast food. In the last decade, for example, Workers United has organized a number of fast-food outlets in Manitoba, including Tim Hortons, kfc, and Taco Bell. The union also led an ultimately unsuccessful certification drive at retail giant uniqlo in Toronto.

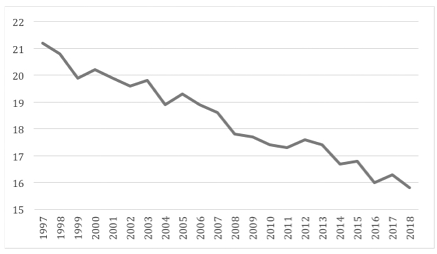

The importance of building union membership in the private service sector cannot be understated. As Figure 1 demonstrates, private-sector union density in Ontario is in decline, thus undermining union power both at the bargaining table and in society more generally. Between 1997 and 2018, private-sector union density dropped from 21.2 per cent to 15.8 per cent. This significant drop is due, in large part, to inhospitable labour law reforms, the spread of precarious work arrangements, and the onslaught of deindustrialization.23

Figure 1. Private-sector union density in Ontario, 1997–2018 (%). Data from Statistics Canada, “Table 14-10-0070-01: Union Coverage by Industry, Annual (x 1,000),” accessed 29 July 2019, https://doi.org/10.25318/1410007001-eng.

The difficulties inherent in organizing precarious private-sector workers in the low-wage service economy are well documented. In the context of state- and employer-led attacks on organized labour and dwindling union density, academic research on union renewal in the 1990s and 2000s focused heavily on the importance of organizing new members and determining the most effective ways to bolster union ranks and union power in the face of neoliberal globalization. Researchers documented the negative impact of anti-union labour law reform and employer resistance on certification win rates,24 debated the role of member activism and the importance of top-down versus bottom-up renewal strategies,25 and considered which strategies and tactics worked best in union organizing campaigns.26

Approaches to organizing new union members became central to debates concerning union renewal in North America in the late 1990s. The ascendency of neoliberal public-policy prescriptions during that period placed downward pressure on unions across many sectors of the economy. As membership dwindled along with union power, some unions experimented with shifting from a service model of unionism to an organizing model wherein the union allocates greater resources toward organizing new members to increase density.27 Ibsen and Tapia argue that adoption of the organizing model as a union revitalization strategy has become more commonplace both within and beyond Anglo-Saxon countries, but that the success of such strategies is at least partially dependant on supportive institutional frameworks.28 Along the same lines, a number of labour researchers have been debating how unions can most successfully use institutional, structural, associational, and symbolic power sources, both internally and externally, as part of renewal efforts.29

As an early adopter of the organizing model, Workers United embraced an aggressive and resource-heavy renewal strategy based on rapid membership growth and strategic corporate campaigning. Specifically, the union was responding to declining membership numbers in its traditionally organized industries by investing in strategic organizing initiatives in the private-sector service economy, where union density is very low but room for growth is very high.

Overall, the growth of employment insecurity and precarity in the private sector has contributed to lower union density and weakened union bargaining power. While there is little question that securing collective bargaining rights could potentially improve wages, benefits, and job security for precarious workers, the pursuit of ad hoc and individualistic coping and resistance strategies – such as quitting or insubordinate behaviour – are far more prevalent than collective responses like unionization.30 Moreover, even in instances where non-union precarious workers seek to exercise their workplace rights, they are far more likely to expose themselves to retaliation from anti-union employers due to the power imbalance in precarious work arrangements.

Despite these challenges, Workers United remains one of only a handful of unions in North America that has aggressively pursued a resource-intensive union renewal strategy based on organizing precarious workers in the private sector. Drawing on elements of structural, institutional, associational, and symbolic power, the union has experimented with a variety of strategies and tactics to help organize workers in corporate chains. In order to bolster the success rate of the union’s certification campaigns, Workers United has sought alliances with broader movements for legislative reform and mounted corporate campaigns to shape public opinion and shame employers into improving terms and conditions of work.31 All of these strategies and tactics were on display in Workers United’s campaign to unionize GoodLife.

The Case Study

GoodLife employees sought union representation for a host of different reasons, but among the top issues identified by workers interviewed as part of this research were the absence of any paid sick days, the expectation to work or recruit new clients without being paid, favouritism by management in the allocation of new clients, unfair wages, and a general lack of respect and recognition for employees’ experience and expertise.

Dahlia Alie, one of only a handful of workers who became very public in support of unionization, complained to the local press that GoodLife fitness instructors started at just $25 per hour – much lower than the industry standard in Toronto.32 Several interviewees argued that while starting wages were low, the bigger frustration was that there seemed to be no standard or guidelines regarding who gets raises, when they come into effect, or through which process.33 “There was no consistency among trainers doing the exact same job for the exact same amount of time. We are paid differently according to region, but some are getting two, three, four or even five dollars more per hour and no one seems to know why,” complained one interviewee.34

The low wages at GoodLife stung even more, according to interviewees, when money spent on earning and maintaining certifications was factored in.35 GoodLife has a built-in mechanism to recoup wages from employees through required fees and accreditations. GoodLife owns Canfitpro, the most widely recognized fitness accreditation organization in Canada. GoodLife requires employees to become certified at a cost of roughly $600 plus an annual renewal fee of $69, making it a very lucrative revenue stream.36 Moreover, advanced courses through Canfitpro are required for employees who want to reach higher levels or lead specialized classes, with GoodLife cashing in every step of the way.37 The union complained to the Globe and Mail that GoodLife’s full-time personal trainers, especially those who were transferred in after takeovers, were not being given credit for fitness certifications other than Canfitpro. The union argued that the company was doing this in order to justify paying experienced trainers lower wages. The move also forced those personal trainers who had obtained certifications elsewhere to pay GoodLife ceo Patchell-Evans for Canfitpro courses.38

In an interview with an online news source, union organizer Tanya Ferguson went on to explain that, for fitness instructors,

once they have the certification they have to pay a company, which also GoodLife owns, for the music that they are going to use in their class. And then they are going to have to pay another company for their uniforms. So people are paying out of their pockets to even work there. And the way the structure is set up, it’s all owned by GoodLife, so there is a resentment and a financial burden. They are actually profiting off of people getting certified to work there in the first place.39

Ferguson claimed that workers were wary of what appeared to be a revolving door system “where more experienced instructors are replaced by fresh recruits, who have to pay all the upfront costs of certification.”40

Expensive certification requirements combined with a strict non-competition clause in employee contracts became major points of contention for GoodLife trainers and fitness instructors. By contractually obligating employees to work exclusively for GoodLife without offering them enough hours per week to make ends meet, the company made it extremely difficult for many people to pursue meaningful careers with GoodLife.41

Unpaid time prospecting in clubs for new clients was also a sore point for many personal trainers. As Sonia Singh explains, “Trainers are expected to recruit their own client base both externally and from within GoodLife’s existing membership. This is accomplished by staffing booths in the club advertising personal training and by roaming around the gym approaching prospective clients with the promise of a free consultation and training session.”42

A veteran trainer interviewed as part of this research explained that when he started more than ten years ago, prospecting was both unpaid and voluntary. In effect, trainers could do as little or as much as they wanted to build their client base. Over time, however, prospecting became an expectation of the job. While not explicitly required, staffing a booth in a club, unpaid, for the purposes of recruiting new clients was strongly suggested by management. Around 2012, prospecting became a mandatory part of the job and an increasing number of tasks were being required of trainers despite the fact that prospecting was still unpaid. Interviewees explained that in addition to staffing booths, they would be required to approach gym members to offer free workouts and call membership lists to inquire about interest in purchasing personal training. Despite all the prospecting legwork, trainers were paid only for the time they spent actually training clients, splitting the hourly rate 50/50 with GoodLife plus a 10 per cent sales commission.

Personal trainers are constantly expected to bring in and maintain clients. “It’s not quite like being an entrepreneur and it’s not quite like just being a worker,” explained one personal trainer.43 Unpaid prospecting work is what gave rise to a class action suit in 2016, and many trainers felt tremendous resentment toward GoodLife for its prospecting policy. In the run-up to certification, the company attempted to get ahead of the issue by instituting a new policy to head off efforts to unionize.

Ferguson described the company’s response as follows: “GoodLife came up with a formula where personal trainers are now paid 50 cents above minimum wage for prospecting, but once they start signing up clients, employees have to pay back the money they were paid before commission.”44 One interviewee explained the dynamic as follows: “At best, prospecting meant borrowing money from a future commission. At worst, it meant working for free.”45

The competitive work environment fostered by GoodLife’s prospecting system also encouraged some employees to work while they were sick or injured. While GoodLife offers employees a basic benefits plan, employees are not covered by workers’ compensation due to a regulatory interpretation that exempts fitness workers. Employers can apply to opt in, but GoodLife has refused to do so, leaving some employees scared of even disclosing workplace injuries.46 “We are required to work out with members. It puts a lot of wear and tear on the body. We use our bodies constantly so we are more prone to injury,” explained one fitness instructor.47 The same instructor complained that working without reliable equipment can also lead to injury. “A microphone protects vocal chords but in a lot of clubs they don’t work which requires you to yell over the loud music, damaging vocal chords.”48 “I’ve spoken to people who work sick or injured either because they won’t be paid or they’re afraid if they say something they’ll lose their class to another employee,” Ferguson told now Magazine. “These are people who work with their bodies for a living. They know safety. [Injuries are not] that common, but when it happens, it truly can be tragic.”49

The lack of clarity over the process by which new clients were allocated by managers to personal trainers was another issue that came up over and over again in interviews. Some interviewees claimed favouritism was rampant while others complained that management would dangle the carrot of a new client in front of a trainer in order to extract more free labour out of them. “There was no system in place for the company to hand out clients that were sold by management,” explained Connor Power, a personal trainer interviewed by the Toronto Observer. “This caused massive favouritism and harassment by club fitness managers towards their personal trainers,” he added.50 “Management had a history of consistently changing policies without consultation,” complained one interviewee. “There was no clear criteria for how clients were allocated. Sometimes it was based on who was friends with a manager, sometimes based on who was the best salesperson, and sometimes based on who appeared to be working the hardest.”51 Eris Collins, a personal trainer who sat on the union’s negotiating team, explained the dynamic in an interview with Labor Notes: “The company frames it so that it’s a privilege to work for them, like, ‘what have you done for me this week so you get a client?’”52

Workers also expressed concern about the levelling-up structure for personal trainers – the mechanism that allows personal trainers to progress through the ranks. One trainer, looking to build his career at GoodLife, explained: “I’d jump the hurdles for levelling up and then management would increase or adjust requirements so that I wouldn’t qualify. Also, criteria might be applied differently depending on the person, based on geography, or favouritism.”53

There was no shortage of workplace issues at GoodLife, but when workers first approached the union about organizing, the assessment of union organizers was that such a venture would be “unconventional and tricky.”54 In traditional union certification campaigns, organizers map out the workplace to better understand internal dynamics, power relationships, and structures of influence. This is accomplished primarily through face-to-face meetings between workers and union organizers assisted by a core committee of inside organizers – committed pro-union employees who are actively engaged in the organizing effort.55

This traditional organizing method would prove difficult at GoodLife given that there were over 40 different worksites, workers often knew other workers only at their own clubs, and many of the workers rented secure apartments in downtown condo towers, rendering impractical unscheduled face-to-face meetings away from the prying eyes of management. “Normally house visits are key for privacy, but the vast majority of workers lived in downtown condos which are very difficult to access. Besides, people were never home. They were either at GoodLife or working a second job,” explained one organizer. These limitations forced the campaign online: “Facebook became the best way to contact them.”56

While the union did not abandon traditional methods altogether, it did shift much of the campaign to online social networks – relying on a mix of text messages and direct messages on Instagram and Facebook to find contacts, schedule meetings, and coordinate activities like card signing. “It wasn’t a luxury or a decision where we could say, ‘how could social media enhance this campaign?’ It’s just the only way that we can run it because that’s where the workers are,” explained Ferguson. “It’s like nothing we’ve done before, and we are learning a lot as we go.”57 Moreover, a traditional house visit-style campaign would be incredibly resource intensive. One interviewee elaborated on this point, explaining that the union’s decision to rely more heavily on social media than on a traditional house visit-style campaign was both strategic and practical: “The union is small, but in a way that forces you to be more creative, like how do you do the most with a tight budget? That requires strategic thinking.”58

The certification campaign was unique given both the tactics being embraced and the group of workers being organized. In general, personal trainers and group fitness instructors often work as independent contractors, making them ineligible for union membership. Others, who work for gym chains like GoodLife, are employees with rights to unionize, but unions are simply not present in the fitness industry. Navjeet Sidhu, of Workers United Canadian Council, told the Toronto Star, “I think we need to not shy away from those challenges as unions. It’s difficult — we’re used to a factory floor, 35 hours a week full-time. But that’s not the reality anymore and we need to start adjusting.”59

While a campaign that relies so heavily on online networks risks escaping the control of union organizers, it was a risk that the union had to take, according to organizers. “If you genuinely engage in social media in a way that actually gives workers a voice, you have no control over what’s going to come,” Ferguson told Rabble.ca. “And in any type of campaign work you depend on having a little control. So it’s definitely outside of our comfort zone. It’s not a perfect system but it does allow for a certain momentum,” she explained.60 Moreover, the fact that most of the workers were millennials gave the union extra confidence that organizing and communicating via social media could pay dividends.61

In addition to the unprecedented use of social media as an organizing tool, the union’s decision to pursue a city-wide certification was another key strategic element in the campaign. Workers United’s organizing department believed that achieving institutional power and leverage for fitness workers required a city-wide approach that would help improve both wages and working conditions for workers across the city, ensuring that non-union clubs could not undercut unionized ones in Toronto.

City-wide certifications are atypical in Ontario but quite common within Workers United. Such certifications are difficult to achieve because workers scattered across many locations often do not know one another, making it more difficult for the union to achieve majority support. However, establishing a city-wide scope clause through certification is fundamental to the union’s overall organizing strategy because it helps build density more quickly and because unions in Ontario are legally forbidden from striking to expand a scope clause.62 “That way, if GoodLife opens a new club downtown, we don’t have to launch a new organizing campaign. Instead, it’s automatically unionized and the workers start out with the union standard from the get go,” explained one interviewee.63

Support for the union was uneven across clubs, with Scarborough and key downtown locations leading the way in terms of support. These clubs tended to have strong inside leaders who were generally already connected to co-workers on social media, making it easy for committee members to connect their people to organizers.64 Initially, organizers paired up with committee members to meet with their co-workers about the union and for the purposes of card signing. Eventually, committee members became well equipped to carry this out on their own.65 Ten per cent of the cards signed were downloaded from the union’s website and returned by conventional mail or electronic scan.

The union also made the campaign public, enlisting the support of long-time GoodLife clients and publishing their words of encouragement and support in a post on a blog on the union’s website dedicated to unionizing GoodLife workers. For example, Emily from Toronto wrote, “The staff at my Goodlife deserve infinitely better wages and working conditions. I support this union drive 100%.” Sharon wrote in to say, “I’m really happy to see Good Life employees standing up for themselves. I am aware that Good Life expects employees to ‘donate’ their time to attend work functions. In other words they are ‘voluntold’ to attend meetings and that’s just the beginning! I appreciate the work they do with a cheerful smile! I honestly don’t know how they do it and would like to see things improve for them!” Kevin, from Toronto, was also supportive: “I fully support your efforts. I have been a member of the plaza club since it opened in 1993 as a Sports Clubs of Canada gym, before being taken over by Ballys and then GoodLife. I have had a trainer at the gym for over 10 years. GoodLife employees deserve their fair share. A company is only as good as their employees. GoodLife’s success is in large part to employees. I hope you succeed.”66

The campaign resonated with both workers and members of the public. By March 2016, roughly half of the workers identified by the union had signed union cards indicating their desire to join Workers United. However, when the union filed its certification application with the olrb, which prompted GoodLife to provide the union with a company list of employees, the union promptly withdrew its application, realizing that it had underestimated the overall number of workers.67 The union refiled its application in June 2016 after securing additional cards.68

Management Retaliation

In the run-up to the certification vote, GoodLife management responded with a sophisticated union avoidance campaign that included both union suppression and union substitution tactics, along with legal manoeuvring with regard to the scope of the proposed bargaining unit. Union suppression “involves coercive tactics designed to plant anti-union seeds of doubt in workers’ minds and to play on their fears concerning the impact of unionization on job security.”69 Suppressive tactics typically frame unions as self-interested and disruptive outsiders whose presence in the workplace will disrupt rather than improve the labour-management dynamic. Union substitution tactics are designed to “increase worker loyalty to the employer, making employees less likely to identify with the union and making it more difficult for workers to see their interests as distinct from the employers.’”70

Ferguson told Rabble.ca that “workers who have supported the union publicly have to watch their backs. Management has come down on us, they did fire an inside organizer, and we ended up having to file charges at the labour board.”71 Dahlia Alie told now Magazine that employees who had been outspoken about workplace problems had been “singled out, demoted, fired and branded as troublemakers. … It hasn’t been pretty.” She added, “There is a lot of intimidation. I would classify the atmosphere in the workplace right now as one of fear.”72 Interviewees also complained about intimidation tactics and surveillance of known pro-union employees. “It was a scary time for a lot of associates. Inside committee members weren’t sure who they could trust,” explained one interviewee.73 However, such incidences did not derail the certification campaign. Union organizers worked to proactively combat union avoidance strategies by inoculating card-signers against anticipated tactics, detailing for them how managers would likely react upon learning about the union drive and preparing them for what managers would likely do and say to undercut the union effort. Armed with this information in advance, card-signers were well equipped and prepared to defend against management’s anti-union campaign tactics once the drive became public knowledge.74

Once the certification campaign got underway, management also responded by announcing the formation of the GoodLife Associate Improvement Network (gain) to bring together workers from various locations to consult on workplace issues. The network, a clear attempt at union substitution, circulated an email to workers explaining that its role was “to represent our colleagues and bring feedback from all of you to representatives at Head Office.”75 The union saw the establishment of gain as a clear effort to undermine union organizing activity, noting that it only ever appeared to be active when a union campaign was also active.76

In the end, management’s union avoidance campaign was only partially successful. Nearly 800 GoodLife Fitness personal trainers and group fitness instructors voted in the union certification election held on 6 June 2016, though workers would have to wait a month for the olrb to release the results because of legal wrangling between the union and the employer concerning voter eligibility. The union had initially filed a certification application that only covered workers at GoodLife locations within the city of Toronto, but GoodLife asked the labour board to also include group fitness instructors from six surrounding cities in the gta primarily on the basis that many trainers travel between clubs for work. According to the union, GoodLife made this request “without those employees’ knowledge or ever having participated in the union drive.”77 Union spokesperson Tanya Ferguson was quoted in a union press release saying, “Workers are disappointed that GoodLife has attempted to manipulate the bargaining unit to avoid having Toronto workers unionize.”78 GoodLife also took the position that fitness instructors and personal trainers should be considered as two separate bargaining units rather than a combined unit as proposed by the union. GoodLife argued that the jobs and pay structures of the respective positions were very different and that while most personal trainers were employed on a full-time basis, most fitness instructors worked only part time.79

A pre-hearing discussion to resolve the eligibility dispute and the appropriateness of the proposed bargaining unit was held at the olrb on 29 June 2016. After much strategic consideration of the certification campaign and the legal implications of the arguments made by GoodLife at the labour board, the union conceded to splitting the groups into two bargaining units and having the ballots of personal trainers and group fitness instructors counted separately. Ferguson told the media, “Had we stuck to saying no, there could’ve be [sic] months and months of litigation. We ultimately decided that it was better to open the box and let the workers speak for themselves.”80 Only those personal trainers working at clubs in the city of Toronto would be eligible to have their votes counted, while group fitness instructors at all locations across the gta would have their votes counted despite the fact that the certification campaign had not reached any workers outside of the city of Toronto proper.

On 6 July 2016, the ballots were counted. Personal trainers voted 181 in favour of unionization with 116 opposed. Two ballots were spoiled. This result was historic in that this was the first group of fitness workers to be unionized in Canada.81 Fitness instructors, on the other hand, voted 147 in favour with 305 opposed. There was one spoiled ballot and an additional 25 that remained in dispute. Because the latter votes would not affect the outcome, determining whether or not they should “count” became moot.

The Toronto Star reported that Jane Riddell, GoodLife’s chief operating officer, “was disappointed in vote results announced Thursday, but respected trainers’ right to unionize.”82 “Obviously, there were issues,” Riddell told the Globe and Mail in relation to the union drive. “A big company has to work hard at staying in touch.”83 Company founder Patchell-Evans told the Globe and Mail that “the union drive is a sign of GoodLife’s success with its employees, not failure,” arguing that his business was simply a lucrative organizing opportunity for a union.84 Whether consciously or not, Patchell-Evans was reinforcing a common union avoidance frame used by employers – that unions are a business and are simply interested in growing their dues base.

The certification vote result was bittersweet for both union officials and workers. The personal trainers had won their union handily, while pro-union group fitness instructors, who had initiated the drive, were extremely disappointed in the result. Dahlia Alie, the fitness instructor who had been quite outspoken about her pro-union leanings, told the media that she felt as though “someone hit me in the side of the head. We honestly thought we were going to win. We had no doubt.”85 It was clear from the lopsided result that GoodLife had effectively managed to mobilize fitness instructors from the cities surrounding Toronto – those who had never come into contact with the organizing campaign – to cast votes against unionization. Alie explained that workers received personal phone calls from the company’s founder and were told by management via email that unionization would mean paying $500 in dues a year. “This is where we lost,” Alie told the media after the vote. “We never got a chance to speak with those instructors personally in order to clear up a lot of the untruths.”86

For its part, the union made clear that its campaign to organize group fitness instructors was far from over. “For instructors who supported us, please rest assured that this is only a temporary setback and that we will continue working with you so that we can refile again within a year’s time,” declared the union in a written statement on its website. The union also signalled that it would seek to organize more personal trainers at clubs outside of Toronto, asserting that “we remain positive that other gyms across the gta and Canada will see the benefits of forming and joining a fitness union. We will continue our efforts to ensure all GoodLife workers have the rights and protections at work that they deserve.”87

While at first glance it may appear that the union’s decision to allow the votes to be counted from the clubs outside the city of Toronto resulted in the fitness instructors losing their union, the decision to split the votes actually appears to have delivered a win to personal trainers that would not have been achieved had all the votes been counted together. In this way, GoodLife’s legal manoeuvring to split its workforce into two separate units for the purposes of the certification vote partially backfired on the company.

While the union’s inside committee of fitness instructors was quite strong and very committed, their limited reach seriously undermined their ability to win. Not only were the instructors in the outer suburbs of the gta not involved in the drive, but many instructors, even in the city, only taught one class per week as a hobby rather than as a job. Connecting with these folks, let alone convincing them of the need to unionize, proved extremely difficult. In contrast, because personal trainers did not travel between clubs, the status of the union’s city-wide certification application was firm. Personal trainers, therefore, did not have to contend with persuading their counterparts in the suburbs to get on board.88

Class Action

In October 2016, as Workers United and GoodLife prepared to negotiate a first contract, Goldblatt Partners llp, a union-side labour law firm, launched a class action lawsuit against GoodLife for unpaid wages – including overtime for prospecting – for all current and former non-managerial, non-unionized employees who had worked for the company in Ontario since October 2014.89 Josh Mandryk, co-counsel on the case, told the Toronto Star, “These are precarious workers, these are young workers, these are in many cases part-time workers. … It’s really crucial for workers in these situations who face challenges standing up to these sorts of policies alone to come together and defend that principle that they should be paid for all their hours of work.”90 The case’s representative plaintiff, former GoodLife employee Carrie Eklund, alleged in the statement of claim that she performed around 100 hours of unpaid prospecting work in one month, along with required paperwork and preparation for classes, all unpaid. “To me, this case is about standing up for what’s right,” she told the Toronto Star. “GoodLife employees deserve to be paid for all of the work that they do.”91 While the class action suit and union drive were not formally connected, the former did put a negative spotlight on GoodLife and helped to validate workers’ grievances.92 Many of the workers interviewed for this research seemed to think that the class action suit played a big role in growing support for the union during the bargaining process. According to one trainer, “the class action lawsuit emboldened people to take on GoodLife. Awareness was high.”93

This dynamic helps to explain growing support for unionization among GoodLife workers in the wake of the certification victory for personal trainers in Toronto. The union understood, correctly, that its partial certification victory limited its bargaining power and therefore set out to grow its bargaining power by certifying more locations before negotiations got underway. Because personal training is such a profitable component of GoodLife, the union reasoned that it was best positioned to make the greatest gains for this group and that those gains would help lift all GoodLife workers. Workers United sent organizers across the gta to test the waters and eventually pursued certification drives in Ajax and Peterborough.

On 21 October 2016, the same day the class action lawsuit was announced, personal trainers at two GoodLife clubs in Ajax, east of Toronto, voted in favour of unionization by a vote of 15 to 7. The company was feeling the pressure and the media coverage concerning the class action lawsuit only drew more worker interest in unionization. On 16 December 2016, GoodLife personal trainers in Peterborough, a city 125 kilometres northeast of Toronto, voted 19 to 3 in favour of unionization.94 The newly certified clubs were simply rolled into bargaining with the consent of both parties. Just over a month later, Goldblatt Partners announced that its class action lawsuit was going nationwide. The action was now seeking $85 million from GoodLife on behalf of thousands of current and former employees.95

Contract Campaign

Prior to the commencement of bargaining, the union established a communications system by appointing a representative from each club who was then responsible for mobilizing trainers to complete the union’s online bargaining priorities survey, which in turn was used by the negotiating team to determine priorities. The size of the team fluctuated over time, peaking at seventeen but contracting during the course of bargaining due to high turnover. One interviewee explained that the average “lifespan” of a trainer, as revealed to the union in bargaining, was just eighteen months.96

Some negotiating team members had been very active in the certification campaigns and naturally transitioned into the role. Others had not been very active previously but emerged as leaders in their respective clubs.97 Very few had any previous union background or experience. While one might hold a preconceived notion that a personal trainer might have an individualistic mindset owing to the self-reliant nature of bodybuilding and fitness more generally, trainers interviewed for this research reported that the negotiating team had a strong collective spirit, borrowing elements from fitness culture that helped to reinforce their efforts: a strong focus of mind, the setting of achievable goals, and the will to work through something difficult and seemingly unachievable.98

GoodLife hired a lawyer to lead negotiations for the company. One member of the union’s negotiating team described GoodLife’s approach to bargaining as follows: “They wanted to break the union and stop it from spreading.”99 The interviewee explained that the employer steadfastly refused to negotiate any monetary differentials between unionized and non-union employees, adding that management’s “view was that there should be no difference between union and non-union workers, so everything they gave the union they said they’d also give to non-union employees.”100 The employer, however, was legally required to negotiate dispute resolution mechanisms for unionized employees, like grievance and arbitration provisions. As one interviewee observed,

The employer didn’t like being at the bargaining table. At first, they appeared to want to win back their own workers, but they became increasingly hostile in bargaining and workers felt insulted. For example, when workers asked for time to do research for their clients, the employer would say that demand suggests the trainers are not even qualified for their own job. They were expecting that workers would be walking encyclopedias. Research was a hobby, not a paid part of their job, even though the employer advertised personal training as a “world class” personalized service.101

Another member of the negotiating team recalled the same exchange: “the Employer suggested that some prep work, like research on how to modify exercises for a pregnant client, was just a hobby and ought to be unpaid. That infuriated team members.”102 One member of the union’s negotiating team wondered if “high level executives were either oblivious or wilfully ignorant.”103

A lack of progress in bargaining a first collective agreement convinced the union to take its contract fight public in the spring of 2017. As part of a strategic corporate campaign designed to target the employer’s brand and increase the union’s leverage in bargaining, Workers United asked the public to help personal trainers to “live the Good Life” by supporting its #RespectFitnessWorkers contract campaign on social media and through a petition. The union designed a logo for its social justice-themed campaign featuring a clenched fist holding up a dumbbell. The raised fist, a worldwide symbol of resistance and unity, came to represent the workers’ determination to win greater rights and respect from their employer.104

The corporate campaign also included escalating direct actions. In April 2017, trainers at the GoodLife club at Dundas Square in downtown Toronto launched a sticker campaign in support of one of the union’s key bargaining demands: paid sick days. On the day of the action, rumours swirled that management would move swiftly to discipline any employee who participated, but the coordinated manner in which the stickers were distributed to all trainers at 5:30 p.m. – the busiest time in the club – meant that management could hardly dismiss everyone. The action boosted morale, gave the workers confidence in their ability to fight back, and built greater solidarity among workers. “Most of us told our clients why we were doing it, and everyone was like ‘good for you, go for it,’” said Danesh Hanbury, a personal trainer and member of the negotiating team. He told Labor Notes that in the wake of the sticker campaign, “I’ve seen trainers less willing to be pushed around by management, where before everyone nodded their head.”105

Community and labour alliances were also an important component of the contract campaign, expanding the union’s social and political networks and providing greater profile and legitimacy to the cause. Such coalitions are typically viewed as key strategic tools for unions, especially when they can be sustained over time.106 The union built ties with the $15 and Fairness movement, which was fighting to raise the minimum wage in Ontario from $11.40 to $15 per hour, along with paid sick days and other pro-labour amendments to the province’s employment standards and labour relations regulations.107 That campaign, headed by Toronto’s Workers’ Action Centre, showcased the plight of GoodLife employees and reinforced their bargaining demands as part of a broader campaign to strengthen workers’ rights across the province.108

Workers United also received assistance from other labour organizations, sending delegates to speak at other union events to encourage union members to circulate the #RespectFitnessWorkers petition and campaign materials in their own workplaces. In Oshawa, Ontario, the union worked with rank-and-file labour group We Are Oshawa to organize a “solidarity workout” outside of a GoodLife club in Ajax. The action, a group exercise class in the parking lot in front of the club, called on workers to “exercise” their rights and welcomed bemused clients to join in as an act of solidarity.109

The union did not stop there. On a warm and sunny afternoon in late September 2017, dozens of unionized GoodLife personal trainers and supporters took to the streets of downtown Toronto to take part in a “Fun Run for Paid Sick Days.” Beginning outside the city’s Union Station, Canada’s biggest transportation hub, runners snaked their way through downtown streets, stopping at five GoodLife locations on their way to Dundas Square. Throughout the run, participants raised awareness about the negative impact of having no paid sick days through literature distribution to the public.110 In a press release related to the event, union spokesperson Adrie Naylor argued that “by not providing paid sick days, we believe GoodLife is prioritizing its own profits over the physical health and safety of its clients and its staff.” Echoing the call of the decent work movement, she went on to say that “if companies as rich as GoodLife won’t address this issue, then we call on the Provincial government to force them to by legislating seven paid sick days for Ontario’s workers.”111

Workers United used these social movement-based strategies, tactics, and frames to build support for their bargaining demands, conjuring “symbolic power” and engaging in “public dramas” in an effort to bring GoodLife clients, the media, and the broader public on board. Jennifer Chun explains that the symbolic power of naming and shaming is rooted in the collective morality of the community, as opposed to the narrow confines of the workplace. These tactics are thought to be most effective when targeting “institutions that are susceptible to public opinion such as governments, brand-driven corporations, and universities.”112 Specifically, these strategies were designed to shame and, in turn, pressure GoodLife into reaching an agreement with the union for the benefit of fitness workers. This approach, bolstered by the class action lawsuit against GoodLife, put the company on the defensive.

Zeroing in on the prospecting issue that had united so many personal trainers against the company, GoodLife management revised its policy in the midst of collective bargaining by announcing that it would pay trainers, both union and non-union, minimum wage for prospecting, none of which would be clawed back. The union’s win on prospecting therefore came before it reached a first agreement with GoodLife. “The change was a form of union substitution,” explained an organizer close to the campaign. “GoodLife wanted to stop the spread of unionization. They knew unpaid work related to prospecting was a mobilizing issue.”113

The union kept up the pressure throughout the fall of 2017 by releasing a series of videos featuring the personal stories of GoodLife personal trainers Vidya and Nyasha, both injured on the job without recourse to paid sick days or workers’ compensation. The union called on the public to share the videos so “we can raise the bar by working together to hold the company accountable, ensuring that GoodLife is a safe, healthy and fair place to make a living.”114

The union’s corporate campaign seemingly paid off when, on 4 December 2017, Workers United and GoodLife ratified a two-year contract with 92 per cent support from GoodLife workers who cast ballots. The union claimed it was the first such contract negotiated in the North American fitness industry. Union bargaining team member Danesh Hanbury told the Toronto Star that the union was able to make significant gains on the issues of paid sick days, unpaid work, and favouritism in the allocation of clients.115 Union representative Naylor, who headed the bargaining effort, echoed that sentiment: “Until this contract, [there was] total lack of unionization, total lack of sick days, limited benefits. This is an industry with a lot of young people where there’s a high rate of turnover.”116

Bargaining resulted in modest wage increases, two to five paid sick days depending on years of service, additional compensation of 2.5 hours every pay period to cover the completion of previously unpaid tasks like scheduling and emails to clients, and agreement on a long list of tasks – such as calling leads and working a GoodLife booth – that would be included in paid prospecting work. Bargaining also maintained the existing optional health and welfare benefits and long-term disability plan, delivered clearer guidelines for levelling up, and won workers access to legally binding grievance and arbitration processes.117

On 7 December 2017, a few days after unionized personal trainers ratified their first union contract, GoodLife management sent all personal trainers across the country an email with the subject line “Unionized Personal Trainers – Collective Agreement in Effect.” The email advised GoodLife employees that the union and the company had reached a negotiated settlement and that the union may continue organizing efforts at non-union clubs. Embedded in the email was a chart comparing terms and conditions of work for union and non-union personal trainers. The chart was designed to convey to the reader that terms and conditions of work for both union and non-union workers would remain identical, with the exception that union members would be required to pay union dues and initiation fees and contribute to the union’s defence fund. “We hope you conclude that a third-party Union is not needed,” read the email.118 The comparison chart itself was extremely misleading because it left out important gains achieved by unionized personal trainers, including a legally binding grievance procedure, leave to arbitration, and new rules to curb favouritism that the company did not extend to non-union trainers. However, the point of the email was not to keep employees impartially informed. The point was clearly to dissuade employees from considering unionization as a vehicle for improving terms and conditions of work at GoodLife.

The employer’s misleading email lends credibility to members of the union’s negotiating team who argued that GoodLife’s overall strategy was to bust the union entirely or, at the very least, prevent its expansion to other locations. By framing the union’s accomplishments in bargaining as useless or even harmful for personal trainers, the employer was clearly looking to undermine support for the union going forward. One interviewee, who was angered by management’s framing of bargaining results, pointed out that “the email and chart failed to acknowledge that unionization had benefited non-union employees as a result of the company’s decision to extend any economic benefit negotiated by the union, like paid sick days, to non-union trainers.”119

One interviewee was concerned that turnover at GoodLife is so high that new employees will not have the background to understand how the union moved the employer, making workers more susceptible to believing that the misleading information presented in the employer’s charts reflects a reality in which there is little to no difference between union and non-union workers.120

While in correspondence with its own workforce GoodLife has refused to give the union credit for any improvements obtained by its employees, the company’s formal response to the ongoing class action lawsuit told a different story. In an affidavit dated 4 January 2018, GoodLife’s vice-president of operations, Michele Colwell, indicated that employee feedback and the collective bargaining process “have both led to the implementation of new or changed terms for Associates. These include payment at minimum wage for time spent by Personal Trainers on administrative tasks, changes to the calculation of prospecting and commission payments, introduction of an education allowance, and implementation of Get Well/Volunteer days off.”121 In short, GoodLife has acknowledged to the court in writing what it steadfastly refused to acknowledge to its own workforce – namely, that collective bargaining has led to improved terms and conditions of work.

Having anticipated management’s negative framing of the new collective agreement, union members, in addition to ratifying the agreement, approved a strategic action plan that “charts a path to build collective power for the future.”122 The union’s strategic decision to pair the contract ratification vote with an action plan – as recommended by prominent US organizer Jane McAlevey – committed members to being part of the process of building the union after ratification.123 Specifically, the strategic plan committed members to fostering “unity and organization among workers in the workplace” through educating new and existing employees about the collective agreement, meeting regularly to talk through issues, resisting divide-and-conquer strategies by management, and supporting the unionization of their non-union co-workers.124 Linda Markowitz argues that sustained worker activism after key events such as certification drives and contract disputes is key to building strong unions that have lasting grassroots support.125

Mark Cleary, a personal trainer and bargaining team member from the Peterborough Portage Place club, provided context for the plan in a union press release: “We were able to push GoodLife to make company-wide changes even though only 25% of GoodLife Personal Trainers are currently unionized. Imagine what we could do if we had even more strength in numbers.”126

The expanded class action lawsuit, finally settled in July 2018, also paid dividends for both unionized and non-union GoodLife employees. A Toronto court approved a $7.5 million mediated settlement of the class action lawsuit against GoodLife filed by Goldblatt Partners back in October 2016 for unpaid work and overtime. The settlement included all current and former non-managerial staff of GoodLife Fitness clubs across Canada who worked for the company during the period covered by the suit. The average personal trainer would see $2,500 as a result of the settlement.127

Evaluating the Campaigns

The Workers United campaign against GoodLife delivered a partial organizing victory and secured a first contract for fitness workers – the first of its kind in North America. The union’s campaign tactics were escalating and multi-faceted, becoming increasingly public and damaging to the GoodLife brand. Moreover, the tactics were rooted in various sources of power: coalition based, institutional, or symbolic. While unions are best known for the exercise of economic power, through the withdrawal of labour, Workers United did not draw on this source of power in its prolonged campaign against GoodLife. Instead, it indirectly leveraged institutional power, capitalizing on the class action lawsuit and impending government legislation to win wage increases and paid sick days. The union also relied on coalition-based power to reduce its isolation and improve its organizational capacity to build relationships and communicate with a broader public. Finally, the union drew on symbolic power by framing the campaign through a social justice lens in order to shame GoodLife into delivering on workers’ key demands.

The union’s campaign effectively exposed the gap between GoodLife’s stated values and its actual practices vis-à-vis its own workforce. “Every Canadian should have a healthy, fit life, but GoodLife doesn’t believe that for its own employees,” explained one interviewee close to the campaign.128 “GoodLife’s values are progressive, but their business plan was not,” explained another. “They opposed paid sick days, and they don’t think workers should have access to Workplace Safety and Insurance Board benefits in cases of injury.”129 The bottom line was that GoodLife’s treatment of its workers was in opposition to the company’s core values.

GoodLife management did eventually manage to contain the spread of unionization in the midst of bargaining a first contract with personal trainers. Moreover, GoodLife’s relatively larger roster of fitness instructors ultimately rejected unionization. Nevertheless, the union’s successful certification and contract campaigns for personal trainers represent significant breakthroughs.

In the end, the union’s specific focus on personal training – GoodLife’s bread and butter – was strategically advantageous in broad terms. The fruits of collective bargaining managed to lift all GoodLife workers, both union and non-union, by negotiating economic benefits that management ultimately extended to all employees. As a result, while the gains themselves were not exceptional, the union agreement provides a solid foundation from which to secure future gains. One member of the negotiating team emphasized the need to build union density at GoodLife in order to improve the union’s negotiating position in the future.130 Bringing new clubs into the fold, however, may prove challenging given GoodLife’s antipathy toward the union, its framing of the results of collective bargaining, and the persistence of the mandatory vote process for certification, which produces greater opportunities and incentives for employers to engage in unlawful union avoidance tactics.131

Employers’ and unions’ strategic choices are very much influenced by external factors, including the role played by the state through the labour relations regime. Union certification procedures are not neutral. In the words of Sara Slinn, “they produce particular incentives, disincentives, and opportunities for employers, unions, and employees, and these affect the outcomes of the procedure.”132 A study by Chris Riddell investigating the impact of union certification processes in British Columbia found that certification success rates were 19 per cent lower under the mandatory vote model and that “management opposition was twice as effective under elections as under card-checks.”133

Employer resistance to unionization is the norm in both Canada and the United States, and the scholarly literature clearly indicates that employer opposition to unions negatively affects the likelihood that a union certification effort will be successful or that the parties will manage to negotiate a first contract.134 Bradley Weinberg has found evidence of a “hangover for relationships that exhibit a turbulent start” as a result of significant conflict in certification or first-contract campaigns. Although the parties avoided a strike or lockout in the first round of negotiations, the fact that the union launched a full-scale contract campaign to help secure the contract, combined with management’s clear use of union avoidance tactics, sends mixed signals about the health of the bargaining relationship moving forward. Despite sustained opposition to unionization by GoodLife management, Workers United has made some headway since achieving a first contract. In July 2019, personal trainers at two GoodLife locations in Oshawa voted to certify, thus increasing the share of the company’s unionized workforce.135

The case of GoodLife complements previous research on determinants of union organizing success and provides new insights into the literature on union certification and strategic campaigns. By comparing and contrasting the strategies, outcomes, and contexts of union organizing and first-contract campaigns, researchers are better equipped to understand how context can affect conditions for success and how specific strategies intersect with those conditions in ways that help or hinder campaigns. For example, juxtaposing the case of GoodLife workers with the seiu’s high-profile Justice for Janitors campaign in Los Angeles – in which a group of immigrant workers overcame incredible odds to win union recognition and economic concessions from building service contractors – reveals how unions are able to draw on different sources of associational and symbolic power to deliver organizing breakthroughs in the private service sector. Both campaigns share important similarities insofar as they relied on a strategy of organizing a large number of small workplaces into a single geographic bargaining unit for the purposes of collective bargaining. Moreover, both campaigns also relied heavily on the use of corporate campaigns and the work of strong inside organizing committees.136 However, they also differed significantly in terms of tactics. In the case of Justice for Janitors, the campaign relied much more heavily on direct actions, broader coalition support, and the intervention of prominent religious leaders. This associational power was key to pressuring the employer into agreeing to a card-check neutrality agreement,137 thus achieving certification, in part, by circumventing the state-sanctioned mandatory vote process in the United States.138 In the case of GoodLife, while Workers United solicited community support, its campaign was not reliant on an external community coalition. Moreover, the union was committed to using the existing labour law regime, and its provisions for certifications based on geographic scope, to help fitness workers achieve unionization and future bargaining power. In each case, the union was responding to a variety of external factors as well as key pressure points and windows of opportunity to shape both their strategies and their tactics in different legal and sociopolitical environments.

While different case studies of union organizing campaigns can offer important lessons and provide meaningful insights, they cannot and should not be interpreted as models, in and of themselves, that can easily be replicated or duplicated in different economic, political, or legal contexts. Nevertheless, the GoodLife case highlights the importance of embracing comprehensive strategic campaigning in relation to both organizing and collective bargaining. This does not mean substituting grassroots organizing with top-down corporate campaigning. In fact, elements of both strategies are evident in the case of GoodLife and were integrated in ways that helped bolster available sources of power. Overall, the organizing and first-contract breakthrough at GoodLife demonstrate that, despite years of decline in private-sector union density, unions do continue to have opportunities to grow, even in industries, like the fitness sector, where precarious employment is widespread. However, similar organizing breakthroughs are unlikely to be achieved if unions are unwilling to think outside of the conventional organizing strategies and power sources that have proven ineffective in the private service sector.

The author would like to thank Curtis Morrison for research assistance and Brock University’s Council for Research in the Social Sciences for research funding.

1. Canadian Press, “GoodLife Fitness Trainers in Toronto, 2 Other Communities Achieve First Union Contract,” Toronto Star, 5 December 2017, https://www.thestar.com/business/2017/12/05/goodlife-fitness-trainers-in-toronto-2-other-communities-achieve-first-union-contract.html.

2. Tom Juravich, “Beating Global Capital: A Framework and Method for Union Strategic Corporate Research and Campaign,” in Kate Bronfenbrenner, ed., Global Unions: Challenging Transnational Capital through Cross-Border Campaigns (Ithaca and London: ilr Press, 2007), 16–39; Sarah Kaine & Michael Rawling, “Comprehensive Campaigning in the nsw Transport Industry: Bridging the Divide between Regulation and Union Organizing,” Journal of Industrial Relations 52, 2 (2010): 183–200.

3. These conceptions of power are drawn from Erik O. Wright, “Working-Class Power, Capitalist-Class Interests, and Class Compromise,” American Journal of Sociology 105, 4 (2000): 957–1002; Beverly Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization since 1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); Marissa Brookes, “Varieties of Power in Transnational Labor Alliances: An Analysis of Workers’ Structural, Institutional, and Coalitional Power in the Global Economy” Labor Studies Journal 39, 3 (2013): 181–200; Jennifer Chun, Organizing at the Margins: The Symbolic Politics of Labor in South Korea and the United States (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

4. Tom Juravich, “Rethinking Strategic Campaigns: Power, Targets and Tactics,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the United Association for Labor Education, Seattle, April 2018.

5. This research relied on in-depth, semistructured interviews with three union officials and nine fitness workers familiar with the campaigns. Workers were recruited using a snowball sampling technique. Length of service varied considerably, but all workers interviewed were employed at GoodLife during the certification and first-contract campaigns. The pool of interviewees was multiracial and comprised both men and women. Interviewees were guaranteed confidentiality as a condition of their participation in the study, in accordance with the ethics clearance granted by the Brock University Research Ethics Board.

6. Ediz Ozelkan, “Gym, Health & Fitness Clubs in Canada,” ibisWorld Industry Report 71394CA, March 2019.

7. Union official, interview by author, 3 March 2018.

8. Statistics Canada, “Table 33-10-0092-01: Canadian Business Counts, with Employees, June 2018,” accessed 29 July 2019, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3310009201.

9. Ozelkan, “Gym, Health & Fitness Clubs.”

10. Wayne Lewchuk et al., “The Precarity Penalty: How Insecure Employment Disadvantages Workers and Their Families,” Alternative Routes: A Journal of Critical Social Research 27 (2016): 87–108; Arne L. Kalleberg, “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition,” American Sociological Review 74, 1 (2009): 1–22.

11. Fay Faraday, Demanding a Fair Share: Protecting Workers’ Rights in the On-Demand Service Economy (Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2017), 8–13.

12. GoodLife workers, interview by author, 3 March and 12 April 2018.

13. Ozelkan, “Gym, Health & Fitness Clubs.”

14. John Daly, “Bulking Up: How GoodLife Became Canada’s Dominant Gym,” Globe and Mail, 27 March 2014, updated 5 June 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/rob-magazine/the-secret-of-goodlifes-success/article17673987/.

15. Ozelkan, “Gym, Health & Fitness Clubs.”

16. “Find a Gym,” GoodLife Fitness website, accessed 21 March 2019, https://www.goodlifefitness.com/locations; “Locations,” Fit4Less website, accessed 21 March 2019, https://www.fit4less.ca/locations.

17. Daly, “Bulking Up.”

18. Michelle Da Silva, “Not So GoodLife for Gym Employees Fighting to Unionize,” now Magazine, 30 June 2016, https://nowtoronto.com/news/not-so-goodlife-for-gym-employees-fighting-to-unionize/.

19. Daly, “Bulking Up.”

20. Sara Mojtehedzadeh, “Inspection Blitz Finds Three-Quarters of Bosses Breaking Law,” Toronto Star, 20 January 2016, https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2016/01/20/inspection-blitz-finds-three-quarters-of-bosses-breaking-law.html.

21. Daly, “Bulking Up.”

22. GoodLife worker, interview by author, 13 March 2018.

23. Larry Savage, “The Politics of Labour and Labour Relations in Ontario,” in Cheryl Collier & Jon Malloy. eds., The Politics of Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 293–311.

24. Timothy J. Bartkiw, “Manufacturing Descent? Labour Law and Union Organizing in the Province of Ontario,” Canadian Public Policy 34, 1 (2008): 111–131; Karen J. Bentham, “Employer Resistance to Union Certification: A Study of Eight Canadian Jurisdictions,” Industrial Relations 57, 1 (2002): 159–187; Felice Martinello, “Mr. Harris, Mr. Rae and Union Activity in Ontario,” Canadian Public Policy 26, 1 (2000): 17–33; Sara Slinn, “An Analysis of the Effects on Parties’ Unionization Decisions of the Choice of Union Representation Procedure: The Strategic Dynamic Certification Model,” Osgood Hall Law Journal 23, 4 (2005): 407–450.

25. Robert Hickey, Sarosh Kuruvilla & Tashlin Lakhani, “No Panacea for Success: Member Activism, Organizing and Union Renewal,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48, 1 (2010): 53–83; David Camfield, Reinventing the Workers’ Movement (Winnipeg: Fernwood, 2011).

26. Kate Bronfenbrenner & Tom Juravich, “It Takes More Than House Calls: Organizing to Win with a Comprehensive Union-Building Strategy,” in Kate Bronfenbrenner, Sheldon Friedman, Richard W. Hurd, Rudolph A. Oswald & Ronald L. Seeber, eds., Organizing to Win: New Research on Union Strategies (Ithaca: ilr Press, 1998), 19–36; Kate Bronfenbrenner & Robert Hickey, “Changing to Organize: A National Assessment of Union Strategies,” in Ruth Milkman & Kim Voss, eds., Organizing and Organizers in the New Union Movement (Ithaca: ilr Press, 2004), 17–61; Richard B. Peterson, Thomas W. Lee & Barbara Finnegan, “Strategies and Tactics in Union Organizing Campaigns,” Industrial Relations 31, 2 (1992): 370–381; Lowell Turner, “Introduction: An Urban Resurgence of Social Unionism,” in Lowell Turner & Daniel B. Cornfield, eds., Labor in the New Urban Battlegrounds: Local Solidarity in a Global Economy (Ithaca: ilr Press, 2007), 1–18; Kim Voss, “Same as It Ever Was? New Labor, the CIO Organizing Model, and the Future of American Unions,” Politics & Society 43, 3 (2015): 453–457; Jane McAlevey, Raising Expectations and Raising Hell (New York: Verso, 2012); McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

27. Bill Fletcher Jr. & Fernando Gapasin, Solidarity Divided: The Crisis in Organized Labor and a New Path toward Social Justice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

28. Christian Lyhne Ibsen & Maite Tapia, “Trade Union Revitalisation: Where Are We Now? Where To Next?,” Journal of Industrial Relations 59, 2 (2017): 170–191.

29. Juravich, “Rethinking Strategic Campaigns”; Gregor Murray, “Union Renewal: What Can We Learn from Three Decades of Research?,” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 23, 1 (2017): 9–29.

30. Fons Naus, Ad van Iterson & Robert Roe, “Organizational Cynicism: Extending the Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect Model of Employees’ Responses to Adverse Conditions in the Workplace,” Human Relations 60, 5 (2007): 683–718.

31. Union official, interview by author, 2 March 2018.

32. Da Silva, “Not So GoodLife.”

33. GoodLife worker, interview by author, 12 April 2018.

34. GoodLife worker, interview by author, 13 March 2018.

35. Da Silva, “Not So GoodLife.”

36. Daly, “Bulking Up.”

37. Da Silva, “Not So GoodLife.”

38. Daly, “Bulking Up.”

39. Ella Bedard, “Who’s Living the GoodLife? Organizing a Fitness Empire,” Rabble.ca, 19 May 2015, http://rabble.ca/news/2015/05/whos-living-goodlife-organizing-fitness-empire.

40. Bedard, “Who’s Living the GoodLife?”

41. Da Silva, “Not So GoodLife.”