Labour / Le Travail

Issue 85 (2020)

Article

More Sugar, Less Salt: Edith Hancox and the Passionate Mobilization of the Dispossessed, 1919–1928

On 1 June 1919, Edith Hancox debuted in front of 7,500 pro-strikers in Victoria Park. Thrust onto the Labor Church’s stage, the mother and shopkeeper won “round after round of applause,” for “scor[ing] the Committee of 1,000,” the shady antistrike organization of Winnipeg’s élite, and comparing “their contemptible actions with the splendid conduct of the strikers.” Hancox is the only woman known to have addressed these massive Winnipeg General Strike congregations. In fact, in spite of their pivotal roles in the confrontation, whether as telegraph, bakery, or retail workers who walked off the job, as housewives of strikers who stretched their household budgets, as operators of a free kitchen for picketers, or as rioters who bullied strikebreakers or allegedly set fire to the street car on Bloody Saturday, the pro-strike heroines of those tumultuous six weeks have largely remained anonymous.1

Edith Hancox is among those lost to what E. P. Thompson called “the enormous condescension of posterity.”2 And yet, emboldened by Canada’s workers’ revolt, Hancox would spend the next decade as one of the most formidable and visible activists in a city notorious for being a hotbed of radicals.3 Her journey traversed the multiplicity of postwar leftist organizations, including the Labor Church, the Women’s Labor League (wll), the One Big Union (obu), and the Communist Party of Canada (cpc). Between 1919 and 1928, scarcely a single Winnipeg working-class demonstration took place in which Hancox did not figure as a public speaker, participant, leader, or organizer. She composed dozens of letters to and articles for the mainstream and radical press. She persistently disrupted political spaces and twice ran for public office. Some of the most significant socialists of the era made a point of making her acquaintance.4 As a champion of working-class women, children, immigrants, and the unemployed, Hancox’s chosen “family” were liberal capitalism’s dispossessed.5 Her community comprised those frequently overlooked by a left that, in spite of its ethnic and gender diversity, prioritized male, Anglo-Canadian, unionized workers. At the apex of her political career, Hancox was secretary of the first national unemployment association in Canada. Whether in the street, in government offices, in smoke-filled labour halls, or in the press, Hancox exposed the plight of unemployed men and women and stressed the value of their indignation and collective agency to foment revolution.

Hancox’s absence in the historical record is hardly unique. Bedevilling their historians, the source materials on early 20th-century socialist feminists’ political struggles are biased, incomplete, and hidden by the very repressions of the capitalist patriarchy they challenged. Despite these obstacles, in the past 40 years, feminist scholars have complicated reductionist portrayals of “first-wave feminism” as maternal in content and white and middle class in composition. We now understand that many feminisms emerged in this period, that identifying with motherhood or its rejection was pregnant with radical and reactionary possibilities, and that class and race were themselves contested categories within women’s circles.6 This article is based on considerable, but nonetheless fragmentary and prejudiced, newspaper reports, Hancox’s journalism, obu and cpc archives, government records, family documents, and conversations with Hancox’s granddaughter, Edith Danna. Edith Hancox’s activism is a reminder that Canada’s interwar left was not monolithically male and that we ought to re-examine the diversity of women who, notwithstanding considerable restraints, thrived there.

Hancox’s gendered subjectivity and her commitment to those marginalized within the labour movement only partially explain her concealed history. Her greatest contribution to post-1919 social movements was in providing the emotional content and support for radical change. The indispensability of affective labour has rarely been central to the study of the Canadian left, even though organizers, like Hancox, have intuitively recognized it as a dynamic aspect of their work.7 Following Arlie Hochschild’s observation that capitalism commodifies the emotional labour of women, feminist scholars, in what has been called the “affective turn,” have contemplated how emotional toil has also been crucial to challenging capitalist patriarchy. In particular, Rosemary Hennessy has theorized how an “affect-culture” materially inflects collective struggles. For Hennessey, affect-culture “is the transmission of embodied sensations and cognitive emotions through cultural practices.” These unconscious “affective relations” motivate and mediate the “social interactions through which needs are met and subjects are formed.” Just as capitalism exploits an individual’s emotional labour, it relies upon an affect-culture that “can uphold the status quo, justify oppressions and lure us into conformity.” But these cultural practices, when they fail to meet needs or delimit the subject, are themselves contested and can spur what another feminist theorist has called “outlaw emotions.” Whether dominant or subversive, competing affect-cultures are the “glues and solvents of social movements.” Affect-culture is always double edged: it can lead to burnout or sour relationships, or it can build a “seedbed of radical critique and revolutionary conviction.”8

Affect saturates Hancox’s socialist feminism. Her writing and speeches bristle with the emotional truths of the unmet needs of the dispossessed. Hancox harnessed the everyday slights and depravations of the poor to bring them together to “haunt” capitalism with their “collective possibility.” The personal and collective constraints of sexism and dispossession limited her influence even as they motivated her activism. The very inequalities that circumscribed Hancox’s impact were, contradictorily, the source of her affective strength.9

The first section of this article explores the evocative contours of Hancox’s illegitimate birth, servitude, marriage, motherhood, immigration, and religious faith and her involvement in the Winnipeg General Strike and its aftermath. The subsequent two sections delve into the expressive terrain of Hancox’s 1920s political activism: first, how her passionate writing and community organizing stoked the “outlaw emotions” of the unemployed, and confronted the relief practices, private charity, poor-bashing, and the dominant affect-culture of liberal capitalism; and second, the reach of Hancox’s ardent revolutionary commitments as illuminated by her views on sexual violence, her challenges to sexism on the left, and her dedication to organizing and defending impoverished single women, mothers, the elderly, youth, immigrants, the racialized, and the colonized.

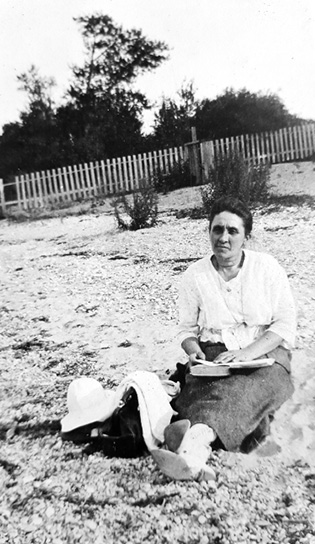

Edith Hancox, circa 1913.

From the private collection of Edith Danna.

Edith Hancox’s Affective Origins

Edith Eliza Gales Angell was born an illegitimate child in Calne, Wiltshire, on 8 August 1874 to Eliza Angell (1856–1926), an eighteen-year-old unmarried domestic servant. Edith’s father, Norman Gales, abandoned both mother and child. As a “fallen woman,” Eliza was socially and economically victimized by a patriarchal conservative order. Those who believe servitude protects the innocence of young single women spout “nonsense [and] lies,” Edith would later write. She knew that the rate of illegitimate births was higher than average among servants, and she hinted that her own mother may have fallen prey to her employer’s advances. Edith’s maternal grandfather, Henry Angell (1827–1898), himself a fatherless child, sheltered his daughter, enabling Eliza to avoid the fate of other unwed, impoverished mothers whose limited options included the poorhouse, infanticide, baby farming, or adoption.10

Edith’s mother married when Edith was four, and before she was a teenager, Edith was parcelled out as a “tweenie,” or a child servant.11 By 1891, at the peak of domestic labour in Britain, the 16-year-old Edith had graduated to “general domestic servant” – and was the only help employed by the young, childless Walker family in Bath.12 Edith’s paid servitude ended in December 1900, when the 26-year-old “spinster” married William Henry Chamberlain, a precariously employed railway porter. Soon after their marriage, Edith bore two sons, Harry and Arthur. In pursuit of a better life for their children, the Chamberlain family travelled in May 1904 from Liverpool to Winnipeg. For five years William found steady work as a blacksmith at Vulcan Iron Works, the city’s largest foundry. He did not witness his co-workers strike against L. R. Barrett, their anti-union manager, in 1919; ten years earlier, William left the employ of Vulcan and he and Edith operated a boarding house near the Central Freighthouse.13

The Chamberlains yearned to escape their proletarian lives. Abandoning their boarding house in May 1910, William took out a $1,200 mortgage and opened a second-hand furniture dealership in a two-story wood-framed house at 1574 Logan Avenue, two blocks south of the Weston Canadian Pacific Railway (cpr) yards and in the heart of the Anglo-Canadian working-class district of Brooklands and Weston. With a storefront on the main floor and a three-bedroom suite above, Edith would call 1574 Logan her home for almost two decades. After eight years of hawking used furniture, baggage, and confectionaries, Chamberlain & Co. became a purveyor in hardware and painting supplies from 1918 on. As a shopkeeper, Edith joined the petite bourgeoisie: although she no longer earned a wage, she remained ensnared in the compulsive power of capital and rooted in proletarian culture. Her business catered exclusively to Weston’s blue-collar families. Neighbours flocked to Chamberlain & Co. to seek Edith’s guidance, air their grievances, and discuss politics; until 1929, the store served as Edith’s organizing headquarters.14

In June 1912, William Chamberlain died after a nine-month battle with cancer, leaving 38-year-old Edith a property holder and a single mother of two.15 Edith was forced to take in boarders, and she struck up a romance with one of her tenants. William John Hancox, seven years Edith’s junior, grew up in Essex; he too, knew the world of servitude – his father had supported the family as a domestic coachman. Originally trained as a woodturner, William Hancox was only able to secure work as a gardener when he arrived in Winnipeg in 1906. Edith married her boarder in April 1913. In January 1915, she gave birth to her daughter, Jeannie.16

Religion proved to be Edith Hancox’s gateway to socialism. She arrived in Canada as a soldier in the Salvation Army, one of many domestic servants inspired by the Army’s promise of spiritual equality and its revivalist appeals to the poor and downtrodden. As Lynne Marks has argued, dismissing the appeal of the Salvation Army as “feminine religious irrationality” offers little historical insight into its resonance among the poor; it is far better to situate the movement as one among many that stressed dispossessed agency and reflected working-class discontent with industrial capitalism. The Salvation Army, prior to its 20th-century transformation into a social rescue organization, offered a working-class affect-culture of chiliastic revivalism that promised spiritual equality and deliverance from individual sin, even if it failed to critique structural inequality. Although “Hallelujah lasses” rarely found space in the upper echelons of the Army, they were encouraged to testify in crowded halls and march through the streets. By doing so, they disrupted gendered conventions in ways that attracted the brash and headstrong Hancox.17

However, Hancox soon tired of the Salvation Army’s “pie in the sky” millennialism. According to family lore, she solicited for Army charity in Winnipeg’s male-only beer parlours. When her superior chastised her for lack of propriety, she argued that a bar patron’s money was as good as anybody else’s and discarded her bonnet, shaken in her spiritual faith. Her later exposés of Army practices built upon a rich tradition of leftist critiques of the “Starvation Army.” In 1921, along with fellow activists, Hancox organized the unemployed housed in the Army hostel. Men were cast out into the elements if they arrived too late in the evening, could not front the 25-cent fee, or complained of the poor conditions. “Wonderful Salvation that would save a man’s ‘soul’ and yet let him perish of cold,” wrote Hancox. Having once been a “Hallelujah lass,” she knew the Army “would probe a man’s very life away for fear he was an imposter.” While she maintained that “the Salvation Army rose as an institution that helps the poor and the outcast,” it was “not the souls of men they trouble about, but the mighty dollar.” “It’s like all other churches,” Hancox insisted, “it’s only the poor in the Salvation Army that help the poor; those who have the good big fat jobs care very little for the poor oppressed.”18

Hancox’s faith was transformed by the “revolutionary humanism” of the Labor Church shortly after its formation in July 1918. The renegade Methodists J. S. Woodsworth and William Ivens, with their sermons on gender equality and worker emancipation, struck a chord with Hancox. It was within these congregations that she found a pulpit and sharpened her critique of capitalist patriarchy. After her debut during the general strike, Hancox preached at no fewer than six Labor Church services in the neighbourhoods of Elmwood, Norwood, and Transcona. Although she maintained ties with Winnipeg’s social gospellers into the 1920s, with her 1922 Communist turn, she resolved that religious belief was no alternative to a political movement: “Christianity which has been tried for two thousand years will never obliterate the injustice and crime to our class, only the workers themselves can change these conditions.” Instead of the Winnipeg General Strike’s defeat leading Hancox into the “chiliasm of despair,” it strengthened an affective millennialism of hope in impending revolution. She replaced heaven with the inevitability of a socialist utopia. “Capitalism is crashing,” she predicted in 1923. “It may be put off by opening up some of the regions near the north pole, but it cannot last more than 50 years in any case.”19

Edith Hancox, Labor Church, Christmas 1919.

From the private collection of Edith Danna.

The 1919 revolt inspired Hancox’s optimism. She was among the thousands sympathetic to the strike who would not de facto benefit from union recognition but who nevertheless valued the possibilities of social upheaval. Aside from her moment atop the Victoria Park stage, little is known about Hancox’s direct involvement in the strike. She may well have participated in the Women’s Labor League kitchen, an invaluable institution that served 1,500 meals daily. She was likely friendly with the women who, in an affront to gender decorum, bullied scab firefighters and destroyed three delivery trucks in her stomping grounds of Weston and Brooklands. By stressing the “splendid conduct of the strikers,” she betrayed little concern over the conduct of her sisters in the streets – she may well have been one of them. During the revolt, if not before, Hancox was befriended by a seasoned feminist radical, the “notorious” Helen Armstrong. Under Armstrong’s guidance, Hancox organized a Weston and Brooklands branch of the wll. She passionately appealed to women to join the wll not only as workers but also as mothers, so “we may prove ourselves worthy to those who will come after us, our children and children’s children.”20

Jeannie Hancox, 10 September 1919.

From the private collection of Edith Danna.

For Hancox, the Winnipeg strike did not end with Bloody Saturday. At a wll “Protest Sunday,” in early September 1919, the 4,000 in attendance resolved to petition and march on the visiting Prince of Wales, demanding the release of the eight strike leaders. After the police threatened to intervene, the wll balked at a demonstration and instead assigned Hancox to deliver their appeal. On 10 September, Hancox and her four-year-old daughter, Jeannie, presented the petition to Edward viii at the Manitoba Legislature. Delegating a non-threatening former Salvationist and mother, with daughter at hand, reflected gender stereotypes, the revolt’s bid for respectability, and Hancox’s emerging status in the wll and labour movement. Recording the event in her daughter’s baby book, Hancox wrote that “it was a terrible crush to get to the Prince and Mother nearly let Jeannie fall into the crowd.” That evening, after Justice Mathers reversed his decision and granted bail to the strikers, she and Jeannie joined a procession of 1,500 to the jail to greet the released leaders. The crowd marched to the Armstrongs’ house and listened to addresses from the Winnipeg martyrs.21

In Hancox’s support for the Winnipeg General Strike she subverted maternal and gender norms. While appealing to women to “protect their children, to shield their girls, [and] to defend their boys from the onslaught of capital,” Hancox also frequently recruited the young to engage in protests. The participation of women and children during a 5,000-strong May Day parade in 1920 symbolized the effects of the imprisonment of the strike leaders on working-class families. The children of the strike leaders sat behind bars on one float, with placards announcing, “Your turn may be next.” On another, children sat on a bed below the inscription “They came like thieves in the night,” referring to the June 1919 police raids on strikers’ homes. “Clambering” onto one of the wagons, Hancox sprained her ankle “but insisted on taking part in the parade.” A month later, she and a troupe of twenty children were ordered off the grounds of the Stony Mountain Penitentiary after serenading the incarcerated strike leaders with labour songs. Hancox evinced a radical motherhood; at the same time, by exposing children to risks and illegalities, she also destabilized stereotypes of the protective mother. And more and more commonly, her activism took precedence over her maternal responsibilities. Her husband enabled her countless hours of rabblerousing by assuming responsibility for the childrearing, cooking, and housework.22

In November 1919 the revolt relocated from the shop floors and the streets to the municipal ballot box. An unprecedented left coalition tried to wrest control of the city from the puppets of the Citizens’ Committee, the cabal of Winnipeg’s business élite who opposed the general strike. A restrictive democracy benefitted the Citizens: property requirements disenfranchised thousands of voters and, since 1890, provisions allowed for absentee landowners to vote and granted multiple ballots for individuals holding property in separate wards. As a candidate for school board trustee in Ward Four, Hancox campaigned for free textbooks for students and collective-bargaining rights and better wages for teachers. The Western Labor News reported that, “as a worker she felt that women should have a place in the administration of school questions.” She “deplored” that the school board sacrificed quality education in favour of cost efficiencies. Hancox pulled a respectable 40 per cent of the vote against her opponent, the incumbent J. T. Haig, a lawyer, businessman, and Citizens’ crony. Fearing labour’s gains, the Citizens’ Committee would later gerrymander the electoral districts to strengthen their vote. As Winnipeg’s year of insurrection drew to a close, Hancox, galvanized by her whirlwind experiences as an organizer, speaker, and political candidate, stood poised to advance the causes of women and the working class.23

An Organic Intellectual of the Unemployed

The time for winking at the class struggle has passed, for we are now at the commencement of a life or death struggle for our existence. Things cannot get better under the present existing order of production, and it is up to us to prepare ourselves to get those things that we need to live. –Edith Hancox, 1922

From late 1920 to the end of 1925, the “Chicago of the North” felt the effects of a worldwide economic downturn. Wages for unskilled workers plummeted relative to the cost of living, work hours were reduced, and thousands of workers and returned soldiers were without employment. Second only to the Great Depression, Winnipeg’s postwar slump was particularly acute compared with other Canadian urban centres.24 It was within this decade of economic uncertainty that the maverick Edith Hancox became a perennial fixture within the city’s left.

Although she participated in many socialist initiatives, it was her advocacy among the dispossessed that earned her notoriety. In addition to her work with the wll, by 1921, Hancox was an active member of the obu both as the business agent of the General Workers’ Unit and as delegate to the Canadian Workers’ Defence League. At the end of the year, she was elected secretary of the newly created Winnipeg Central Council of the Unemployed. The council was endorsed by the obu and the Independent Labour Party of Manitoba (ilpm). At an unemployment conference in March 1922, which represented 90 different labour and veterans’ organizations, including the obu, ilpm, and the Workers’ Party recently formed by the cpc, the municipal unemployment council was folded into the Manitoba Association of Unemployed with Hancox as its first secretary. By June, she had stepped down from the obu and joined the Workers’ Party. Six months later, Hancox’s organizing skills were put to use as Winnipeg hosted unemployment activists from across Canada to form the National Committee of Unemployed Workers (ncuw). Elected as the ncuw’s able secretary, Hancox would co-write several national bulletins that described local, national, and international unemployment conditions and provided propaganda to coordinate local protests, which were published in leftist newspapers across Canada. Although the ncuw was frequently on hiatus, she remained its secretary until it dissolved in 1928.25

Hancox’s public speeches are missing from the historical record. However, her journalism offers a facsimile of her soapbox orations. Between 1918 and 1928, she wrote no fewer than 40 letters and articles to the local press, the obu Bulletin, and the Communist Worker – a remarkable achievement considering that she surely had only a rudimentary formal education. Her prose differs from the social work orientation of Rose Henderson, the poetic sensibilities of Gertrude Richardson, the theoretical sophistication of Florence Custance, or the national organizing missives of Annie Buller and Beckie Buhay. Instead, her personal and affective journalism echoes the style of Out of Work (1921–23), a fortnightly paper published in Britain under the auspices of the Communist-led National Unemployed Workers’ Movement. With a circulation that peaked at over 60,000, Out of Work “addressed its readers” in an “intimate way, more reminiscent of a private letter than of a newspaper.” Unsurprisingly, Hancox was an Out of Work reader and one of its few Canadian correspondents.26

Hancox’s journalism conjures romantic, gothic, and Spencerian tropes: capitalists are the “robber class”; social workers, religious charities, and the police are “parasites”; workers are wage “slaves”; and capitalist profits are “blood money.” Her writing pulsates with accusation, frustration, disappointment, and hope. Although she was an avid reader, her soapbox prose never nodded to literary inspirations. She clearly appreciated radical education, even working to establish a labor college in the city. Yet one senses that Hancox’s journalism, like that of other Out of Work correspondents, emerged organically from her particular experiences and reflected the emotions, beliefs, and opinions circulating in the working-class communities to which she belonged. In her speeches and her writing, Hancox avoided the abstract, directly addressed her audience, and showed, by example, how “she too had suffered under the capitalistic system.”27

Hancox represents what her contemporary, Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist, called the “organic intellectual.” Anticipating Hennessey’s “affect-culture,” Gramsci theorized the importance of affect as a hegemonic and counterhegemonic force. He criticized intellectuals who were so bound to a Lockean conception of “man” as a rational actor responding to “economic necessity” that they ridiculed the emotional content of politics as the “stuff” of the “common people.” “The intellectual’s error consists in believing that one can know without understanding and even more without feeling and being impassioned,” he wrote in his prison notebooks. “Political passion,” Gramsci argued, “is born on the ‘permanent and organic’ terrain of economic life but which transcends it, bringing into play emotions and aspirations” that can serve to challenge the logic of capitalism. Affect is “necessary,” he insisted, “to sharpen the intellect and help make intuition more penetrating.” As an organic intellectual, Hancox drew upon the revolutionary passion of those around her to serve as the wellspring of organization.28

As she traversed what Gramsci described as the “passage from Feeling to Understanding and to Knowing,” her politics expanded. In a letter to the Winnipeg Tribune just months before the general strike, Hancox presented a labourist and feminist proposal for an inheritance tax. She disapproved of income taxes because they unfairly burden workers and allow the “indolent and lazy rich” with their “invested and unearned incomes” to get off scot-free. A death tax, Hancox argued, would prevent the rich from bequeathing their entire fortunes “to their idle sons and daughters.” Defending the unpaid social reproduction of women, Hancox’s proposal allowed for a proportion of a deceased’s savings to go to his wife, “for often they have helped the man to get much of what he is worth.” In an affective twist on the Marxist maxim, she sought not “for each according to their ability, to each according to their needs” but rather that “everything should be done … to aid and enable each and every one to reap to the fullest extent all the capabilities and energies that they possess, and then to enjoy them during their lifetime.”29

By 1922, Hancox had abandoned redistributive schemes in favour of revolution. She passionately believed the “overthrow of the capitalistic system was essential to universal happiness, prosperity and peace.” At her most optimistic she reasoned that the revolution could be won through peaceful methods, but she did not doubt the wealthy would resist. She subscribed to the labour theory of value, contending that workers “produce all the wealth there is,” and understood, in the Marxian sense, that workers “only own their Labor power.” The survival of the fittest, she observed, was “not now to the strong” but to “the fellow who is slick and cunning enough to put something over the other fellows.” Those who heralded the self-made “man” failed, wrote Hancox, to realize that “we are producing commodities, socially, dependent upon each other in every phase of that production” and therefore what is produced should be distributed equitably. The unemployed, she maintained, deserved a portion of the collective wealth not only because they were once, or might well be again, commodity producers but because they are part of “humanity” and “have a right to live.” Although Hancox never referred to Marx’s concepts of the relative surplus population or the industrial reserve army, she argued that the failure of the workless to contribute to the economy was no fault of theirs but that of an economic system that relied on the unemployed to “beat down the worker’s wages” and “make it easier for the master class to take advantage of an overstocked labor market.” Unionized workers, in her estimation, needed to recognize that they were “no higher than the lowest among [them].” They had to overcome their “pride,” “sheer downright laziness and indifference,” and their “ignorance of [their] true position in society” and align themselves with those out of work.30

Unlike the 1919 strike leaders who redirected their energies to electoral politics, Hancox illustrated the limitations of political representation, even while offering herself as a candidate. In addition to her 1919 campaign for school board trustee, she ran for city council in 1923 in Ward Two under the banner of the Workers’ Party. She mustered only a few hundred votes and placed last out of eight aspirants, losing to incumbent labour candidate Thomas Flye and finishing behind her erstwhile ally, the wll contender, Helen Armstrong. Although Hancox and Armstrong had split over the former’s allegiance to the cpc, they shared a concept of leadership that stressed mobilization over representation. As Armstrong told a voting audience in 1923, she disagreed with her husband’s vanguardism: “I don’t believe the world is going to be saved by putting a handful of scientific socialists at the head of things.” Hancox agreed: “No leader or group of leaders will make for progress; only the massed action by the people.” Masters, she argued, will not “save us.”31

Hancox also questioned the efficacy of municipal politics. She was convinced that city council was a “fortress of big business.” The Citizens’ Committee, under various guises, she wrote, used “underground methods” to “get candidates whom the workers think are their friends” but “who would serve private interest only.” They operated a “fascist organization” that kept “the workers in subjection and fear.” During the electoral campaign of the “sabre-rattling” and reactionary Colonel Ralph Webb in late 1924, Hancox paraded 600 unemployed to the Marlborough Hotel to challenge the Citizens’ pick. During Webb’s tenure as mayor (from 1925 to 1927 and again from 1930 to 1934) he did much to disarm leftist representatives on council. His red-baiting, including the 1926 threat to throw Winnipeg’s “troublemakers” into the Red River, destabilized the grassroots activism of Hancox and others. And, as Hancox learned, neither the electoral success of labour mayor Seymour Farmer (1922–24) nor a strong minority of left-leading councillors throughout the 1920s improved the administration of relief for the unemployed.32

Hence, Hancox prioritized the mobilization of the unemployed over the unionized worker and electoral politics. She organized more workless demonstrations and headed more unemployed delegations to government officials than any other Anglo-Canadian activist prior to the Great Depression.33 She was so crucial to the movement that when she fell sick, rallies were cancelled. In 1921, Citizen mayor Edward Parnell’s attempt to co-opt the unemployed “ambassador” by offering her a seat on the Winnipeg Joint Committee on Unemployment backfired: she used the position to obtain insider knowledge on the city’s relief practices. Although she generally avoided left partisanship and readily worked with rival working-class organizers, Hancox took to task city labour councillor W. B. Simpson, who, as the chairman of Winnipeg’s Social Welfare Commission (swc) between 1921 and 1923, oversaw austerity measures to limit the financial burden of poor relief on city taxpayers. Hancox also held to account Mayor Farmer’s minority government for echoing the view that relief was a charity and for prizing fiscal restraint over social assistance. Still, until the mayoral election of Webb in late 1924, the concerted pressure of the organized unemployed, the threat of social unrest, and a handful of sympathetic politicians and labour leaders made Winnipeg’s welfare rates among the highest in the country. Adamant that welfare ought to be the shared responsibility of all three levels of government, Hancox regularly led protests to the provincial legislature and appealed to the federal authorities to inaugurate the cpc’s demand for national noncontributory unemployment insurance.34

Echoing Mary Wollstonecraft, Hancox believed relief was a matter of justice, not charity. “If I had my way, I’d banish every charity from off the face of the earth,” she told the swc in 1923, “and make the state look after those who are unable to look after themselves.”35 “Damn charity,” she insisted, appeased only the whims of wealthy individuals who had acquired their riches through the robbery of the working class. The socialist duties of a people’s government would eradicate the need for charity. The state “should not peddle support and keep in power those who have robbed the mass of the people of their rights” but instead “should find ways and means for creating employment for those out of work” and “hold the means of wealth that lie in the country, for the benefit of the people in trust.”36

Winnipeg did the opposite by employing a series of well-tested tactics to limit those eligible for assistance. Relief investigations and work-tests weeded out the “deserving” from the “undeserving.” The denial of relief and the threat of arrest to able-bodied single unemployed men who refused to leave the city to work in logging camps or as farmhands, as well as a six-month residency requirement, prevented transients, recent immigrants, and those without families from taxing the relief coffers. As many as two-thirds of the unemployed in the city were ineligible for aid. Relief scrip, or in-kind relief instead of cash handouts, limited the autonomy of the workless and upheld the principle of less eligibility by ensuring welfare was less attractive than the worst-paying job. The food made available for relief recipients was of questionable quality, and suppliers became mired in scandal. Basic necessities such as fuel and clothing were habitually denied to the unemployed. The city provided a maximum of only two months of rent payments for unemployed families and did little to prevent evictions by bailiffs. The dilapidated cpr Immigration Hall was occasionally used to house the single unemployed. And, like every municipality, Winnipeg closed its relief offices in the spring, offering provisions only to the neediest married men, maintaining that there was enough seasonal labour that no able-bodied worker should be without employment.37

In her writing, and through the organization of the unemployed, Hancox challenged all of these measures of austerity. She mobilized the unemployed around the cpc slogan of “work at trade union rates or full maintenance” and insisted that all relief be paid in cash. She dismissed the reports of relief investigators as not amounting “to a string of beans” and instead questioned “the character and aims of the officials administering relief.” In the early spring, Hancox led perennial demonstrations, some with as many as 4,000 participants, which often won the extension of relief for another few weeks. As winter approached, she brought crowds into council chambers to pressure authorities to vote in the necessary relief funds for the winter. Not only did Hancox organize protests, but she pioneered antipoverty casework in which she brought cases of those unfairly treated by the swc to the attention of local authorities. Casework, inconsistently practised in other urban centres in the 1920s, became a staple of unemployment movements during the Great Depression.38

Hancox disagreed with municipal policies and practices designed to coerce the unemployed to work. The woodyard as a “work-test” was repugnant to her. Only “crazed capitalists” who were suspicious of “doles,” she argued, would think of employing the “uneconomic method” of hand-sawing when motorized circular saws cost less and require less labour. The obligation to cut a quarter cord of wood either for a pitiful wage or for three meals and a bed proved a constant source of contention for the relief workers Hancox organized. A limited number of saws meant they had to wait their turn in the winter, often without appropriate attire. The saws that were provided were dull and rusty. Agitation at the woodyard, including a November 1924 strike led by Hancox, won modest gains, including a heated shelter, rubber boots, free meal tickets, and the lifting of the work-test for the physically unfit. Logging camps and farm labour were also no panacea for unemployment, argued Hancox. She fought against Winnipeg sending youth and the sick to work outside the city. Farmers, especially over the winter, offered little more than five dollars a month plus room and board – a wage well below living standards. She pushed the province to investigate the filthy accommodations and lack of recreational facilities for bush workers. In 1922, she charged the city with subsidizing bush contractors with taxpayers’ money when it promised to cover as much as two-thirds of a logger’s wages in his first three months in the camp. Work for the unemployed should not force them out of the city, she argued, or have them engage in meaningless tasks. “Time after time,” Hancox told city council in 1923, “you have told us you would provide useful employment and you never have.” When Winnipeg did employ the workless on snow removal, sewer, and water and road works, they only did so at a “scab rate of wages,” displacing permanent workers.39

Hancox brought the unemployed together to fight for their basic necessities. Adequate shelter was a priority. In May 1921, after Mayor Parnell had declared that there was no homelessness in Winnipeg, Hancox and other activists found more than 75 unemployed men sleeping in the railway yards and in boxcars. Proving that the homeless were bona fide Winnipeg citizens, the activists succeeded in forcing the city to pick up the bill and provide the majority with temporary hotel accommodations. Hancox also contributed to a campaign to raise awareness of the sordid conditions at the Immigration Hall, where male relief recipients were housed in tiny, poorly ventilated rooms and denied access to the washrooms. Married relief recipients were not treated any better. The swc “grumble about high rent, but they do nothing to show up the grasping, greedy landlords who are charging exorbitant rents,” complained Hancox after she won $25 in back rent from the swc for a family of four whom the commission had kicked out of their house, forcing them to bunk in an attic.40

By making public the bare cupboards of the poor, Hancox politicized the normally private concerns of the household. The demand for sustenance was not an empty metaphor; for Hancox, steeped in the radical politics of consumption, it was the staple of revolution for those “living in a state of semi-starvation.”41 She expounded on the quality of the relief rations, “the miserable bits of groceries” – from mealy porridge to stale buns – that, in Hancox’s estimation, were “simply chicken feed.” In early 1921, she railed against the grocery provisions for war widows: “very luscious living, one cup of sugar to four bags” of dry grains. The unemployed siege of city hall in June 1924 and the police violence it provoked took place only after married men, wives, and children “had for weeks existed only on bread and water or weak tea,” wrote Hancox. “A hungry man is an angry man,” she warned. By placing the lack or quality of food at the centre of capitalist relations and socialist alternatives, she advanced “rebellions of the belly” into forms of cooperative and organized disruption.42

Fighting for basic necessities was one means of upholding the dignity of the unemployed. When relief officials, politicians, the well-to-do, and the press impugned the workless, Hancox rallied to their defence: “Those who call homeless and unemployed men bums cannot have known what it is to be out for work for weeks and months together and then return to work with low vitality and lessened morale.” Although Hancox rarely consumed alcohol, she sneered at those who blamed “John Barleycorn” for poverty; underfed and poorly clothed children persisted even after the enforcement of prohibition, after all. In 1921, Simpson and the swc promised to weed out relief “imposters,” contending that relief pauperizes recipients; Hancox called this contention “piffle” that “does not pass in these enlightened days.” Who would seek to game the system, she asked, given the “humiliating way” relief is “doled out”? The real “pauperizing,” Hancox charged, was of the “bosses’ children” and “also the dogs and cats of the privileged class, who have comforts and beds that thousands of children die for lack of.” That relief officials required recipients to sell “luxury” goods (such as vehicles, telephones, and gramophones) in order to qualify for aid was nothing less than “highway robbery.” In 1928 Hancox scored Gertrude Childs, the swc superintendent since 1921, who had declared that a “habit of dependence” among the poor was responsible for the rise in relief rolls. “According to this well-fed Boss Agent,” wrote Hancox, it is more to the credit of the workless to “suffer cold, misery, starvation, pain and even death, than to live to expect any unemployment relief.”43

Hancox’s emotive allegations were met with opprobrium, denial, and ridicule by those caught in her crosshairs. The “versatile Mrs. Hancock [sic]” discovered a “mare’s nest,” claimed the Great War Veterans’ Association in 1921, after she had charged the association with “gross profiteering” in its distribution of food to the unemployed. “One Who Knows” complained that Hancox’s criticisms of domestic service proved she sought not to help the “girls” but to “make trouble.” The swc dismissed her numerous charges against the commission as “unfounded.” Rev. Dr. E. G. Perry, swc executive member, teased Hancox for seeking unwarranted “publicity” and suggested that if charity were abolished, the state would be compelled to establish poorhouses. When Hancox “deposited a half loaf” of the bread offered to relief recipients for inspection by Mayor Farmer and the rest of city council, they mocked the complaints of the poor and derided Hancox’s feminine ignorance, by sharing the bread “in the manner of an old-fashioned love feast.” Her props and theatrics did not backfire, as the press contended; they were less about winning sympathy from politicians than about building a movement. But laughing at her expense was a favourite pastime of the Manitoba Free Press and the Winnipeg Tribune. She caused “sparks, of no unusual brilliancy or abundance, but nevertheless quite certain sparks,” that made for entertaining copy. Sardonic attacks were part of the affective arsenal of a capitalist patriarchy. It was easier to poke fun at Hancox’s gender and her passionate organizing than to treat seriously her charges.44

An Expansive Socialist Feminism

I trust women will soon educate themselves to produce a system … [in which they] shall not be regarded as a commodity by the other sex. –Edith Hancox, 1921

Feminist values permeated Hancox’s ardent socialism. In 1916, after Manitoba had succumbed to the tireless lobbying of feminist reformers and granted women the franchise, Hancox preserved a newspaper clipping of the Political Equality League in her daughter’s baby book. In doing so, she appropriated a commercialized product sold to mothers to record non-political milestones, repurposing it as a feminist legacy book for her daughter. For Hancox the franchise was a breakthrough both for her daughter and for women’s rights. However, she believed gendered exploitation and inequalities persisted beyond the ballot box. In 1918 she called for greater sex education because “there is too much … silly prudery existing in the world.” She demanded sterner moral sanctions against perpetrators of sexual violence. “I believe we would have a better world if the sins of our men were shown up more,” she insisted. Women and girls were unequally faulted for sexual impropriety, while the indiscretions of men were dismissed: “I know many a young girl cannot look and smile at a boy but someone will believe she is fast.” Hancox’s arguments were entangled in a web of Victorian puritanism. She blamed women’s attire as “altogether too … suggestive” and chastised prostitutes as “pariahs.” She was not defending female innocence but demanding an equality of shaming: “If our boys go wrong they should suffer as much as our girls.” Hancox upheld the heteronormative controls of mixed-gender schools and fell short of other feminists of the era who advocated women’s sexual freedom. Yet she stood apart from many suffragists by calling out victim-blaming and a mainstream culture that endorsed male sexual conquest.45

Not only were working-class women subject to sexual violence, but Hancox believed they were often forced into marriage out of economic necessity. During the 1920s, Red Scare propaganda alleged that Russia was “nationalizing” its women by driving them into state-decreed marriages. Not so in Soviet Russia, Hancox argued, but such was their fate in Canada. She charged that Ottawa foisted marriage upon working-class single women by refusing to provide national unemployment insurance. She did not join other feminists of the era in advocating birth control, although she believed that without revolution, family planning would be the “only remedy left to” mothers seeking emancipation “from a system that is crushing out all home life, killing our children by the thousands, stunting their growth and making their lives unbearable.”46

For Hancox, male chauvinism was a scourge of both capitalism and its counterhegemonic alternatives. Following the general strike, Hancox challenged the patriarchal politics of the obu. As Todd McCallum explains, from its founding the obu fostered a masculine counterculture that emphasized class struggle and relegated gender issues to secondary status. Although an accurate assessment, McCallum misses how the appeals of Hancox and the wll for membership in the obu Central Labour Council were ultimately successful. After several petitions for their inclusion narrowly failed an executive vote, Hancox and the wll appealed once more for full obu affiliation in the winter of 1920. Some delegates questioned the trustworthiness of women and thus advocated restrictions; however, this time, the motion passed. The council even accepted the wll’s internal membership criteria that allowed women wage earners, those related to obu men, and even those, like Hancox, “whose principles are obu” to be eligible for full affiliation. The wll’s victory over the obu’s chauvinists evinces the strength of post-1919 feminist activism on the left and reveals, as Peter Campbell suggests, that the sexism of working-class men “was susceptible to change.” Of course, wll members still had to contend with “less formal” barriers and ridicule. Smoke-filled meetings may have deterred some women, but Hancox merrily lit up with her comrades. In the early 1920s, obu women were chastised for non-attendance, had their voting rights challenged, and were “fired” from special committees. However, by 1925, at least one woman had been elected to the council’s executive. Hancox shared the principles of the obu, but the union as a whole wrestled with a principled stance on gender equality and inclusion.47

The extent to which sexism undermined Hancox’s involvement in the cpc is unclear, although as the most visible Anglo-Canadian woman Communist in Winnipeg in the 1920s, she no doubt felt at turns tokenized and isolated. As Joan Sangster indicates, the party vacillated between denigrating women as inherently reactionary and praising them as revolutionary heroines. The cpc bemoaned the lack of class-conscious industrial women workers in the party and depreciated the supposed “parlour” socialism and social reproductive work of Communist housewives. Hancox, being neither an industrial worker nor the wife of a party member, failed to comport to the cpc’s rigidly gendered categories, and despite her militancy, her business ownership may have cast some doubt on her revolutionary authenticity. For her first three years in the party, Hancox appears to have been an equal to her male allies and was not shunted to the usual behind-the-scenes silos of women’s work. In 1925, cpc organizer Malcolm Bruce complained of the “loose, uncommunistic and lackadaisical” efforts of Winnipeg party members in organizational and educational work – a criticism that at least implicitly belittled Hancox’s own efforts. In any event, unlike Custance, Buhay, and Buller, Hancox was never on the cpc’s executive or within its inner circle of power.48

As she did in the obu, Hancox pushed for the cpc to confront the “gender question” while concomitantly appealing to women to join the class struggle. After she spoke on women’s work at the fourth national convention for the cpc in Toronto in September 1925, the Worker reported that “for the first time in the history of the Party have women members urged the Party as a whole to consider their end of the work more seriously.” A year earlier, Hancox had returned to the newly reorganized Women’s Labor League, now under the stewardship of Custance, the director of the cpc’s Women’s Department. In Custance, Hancox found a kindred spirit. Hancox embodied much of the director’s thoughts on organizing women, while Custance’s editorial decisions in the Woman Worker (1926–29) encouraged the personalized and affective appeals of its contributors, Hancox included.49

As a wll delegate, Hancox participated in the pan-left Labor Women’s Social and Economic Conference in 1924. At its March meeting in Brandon, Hancox urged the delegates to join “the political struggle side by side with men,” criticized the weakness of “women’s organizations fighting alone,” and engaged in heated debates with other attendees in support of Russian revolutionary methods over the British Labour Party’s “evolutionary actions.” She chastised the feel-good, “reformist,” and social work orientation of many of the conference’s members and sought to make the conference a federated body in order to bar from the executive “reactionary and bourgeois individuals” who indulged in “sentimental trash” and who sought only to “crush any militant effort which may be put forward by working women to free themselves and their class.” In April 1925, after the conference had failed to endorse mass actions, Hancox and other wll members canvassed factories and working-class homes and distributed over 1,000 leaflets to “win women over to the idea of organization.”50

No matter her party affiliation, Hancox desired to emancipate women workers. “Hasten the day,” she wrote, “when women wage slaves shall be free, absolutely free.” She exposed how a patriarchal liberal order disguised female dependence upon wage labour. Women made up a quarter of the Winnipeg workforce in 1921, despite the prevalence of the male-breadwinner ideal. Protections for women workers, like the haphazardly enforced minimum-wage laws, were entirely inadequate, Hancox argued. She scoffed at the commonly held belief that “girls” were working for pin money or extravagances or that their wages were a supplementary bonus for their family; their income, she explained, was essential to their life and health. In a 1927 article in the Woman Worker, she describes a fictional Alice, a “pale-faced girl of twenty years of age” who laments a pay cut to $8.25 a week at a laundry. Alice feels duped, having believed “that if we work hard and serve our employers well that we should be sure to rise higher, make our way in the world.”51

The affective resonance of her years as a servant rang loudly in Hancox’s 1920s activism. In 1921 more than half of the city’s female workers continued to labour as domestics. In Hancox’s opinion, the “drab and dreary” toil of the domestic servant made her “the most exploited of all the working class.” Domestics, she contended, were “more like slaves than human beings.” “The butt for everyone’s bad temper,” the servant laboured long hours, “scouring away other people’s dirt and grime,” under constant surveillance and the prospect of dismissal. The mistress “treated [the servant] as a commodity” instead of protecting her “sister, who is aiding her in her home work.” Privilege undermined gender solidarity. Sexual violence, Hancox reported, loomed over the work of the domestic. Masters too often “barter for a woman’s honor with their filthy lucre.” At meetings of unemployed domestics and in the press, she denounced the city’s practice of denying welfare to workless women if they refused domestic jobs. She understood intimately that while their employers demanded loyalty and gratitude, servants felt the shame of subservience and the fear of punishment and violence.52

Hancox personalized the plight of other working women. Down and out in Toronto for several months following the 1925 cpc convention, Hancox picked up odd jobs to pay for her return fare to Winnipeg. For 24 hours she laboured in the pantry of the Hotel Florence on King Street to pocket three dollars in wages. Workers “who eat in these places,” she argued, are ignorant of the “conditions and hours” of the “girls, men and women” who “slave their lives out” to serve them. The basement kitchen was dark, and a “hole full of dirty stinking water” below the furnace created “extremely unsanitary [conditions] for the girls working close by.” These “kitchen girls” supplied their own aprons, laboured long hours, and were hounded by management. Hancox was fired for talking back to the chef (also a “wage slave” but one with the “master class viewpoint”) after he accused her of not boiling the coffee water. She felt as though she was “treated as [a] robber” when the boss opened her private package, which contained more than a dozen copies of the Worker. As a parting shot, she shamed the boss – “though many of them don’t possess much shame” – for handling her personal items and scolded him for his “blood money” profits. Hancox recognized that her personal indignation did nothing to stop the “masters” who “rob, exploit, bull, and browbeat the workers at every turn”; her moonlighting as a kitchen girl would end, but for her co-workers the “vicious circle [went] on.”53

If women were exploitable wage workers, they could also be denied the opportunity to sell their labour power. Like no other, Hancox laid bare the reality of women’s unemployment. By January 1921, before any attempt was made to organize workless men, Hancox had, through the wll, mobilized “house workers, waitresses, unemployed girls and women and those working part time in factories.” At massive workless rallies that winter, she sought to overcome the ignorance of unemployed men and her leftist allies who knew “absolutely nothing of what the women and girls had gone through.” Hancox and Winnipeg’s unemployed women agitators forced the city to offer a female-only relief office every winter for the entirety of the postwar depression. Even then, unemployed women fought against their discrimination under the welfare regime. Arguing that they “are receiving a raw deal” and that men were “being treated far more fairly,” Hancox noted how single men often received several dollars more a month from the city than the seven dollars doled out to unemployed women. The situation should be reversed, she lobbied, as living costs for women, from clothing to the discriminatory higher rates charged for room and board, were far higher than that for men. Hancox castigated Winnipeg’s swc for forcing women into “unseemly and unfit,” part-time, and poorly paid work, and she counselled her sisters to demand assistance rather than take such meagre employment. The work-test and relief investigations targeted the eligibility of workless women, too, and often led to consequences unique to their gender. In an attempt to wound liberal sensibilities concerning female virtues, chastity, and decorum, Hancox targeted low wages and paltry relief as driving “any woman, let alone a young friendless girl to desperation.” She told of demeaning physical inspections of unemployed women by relief officials and presented allegations against an examining city doctor for sexual assault. “Many times women are insulted by advances made to them by these investigators,” revealed her fellow activists, “[and] if the woman should fall for same, it is used against them, they are immoral, and as such must not be granted the necessities of life.” Departing from the moral regulation of middle-class female social workers, Hancox refrained from judging women for their sexual decisions. Male relief recipients rarely had to answer questions about their sex lives. Their female counterparts did so, routinely.54

Of course, the majority of women’s interactions with the state and capital were mediated by their familial affective relations. In spite of their detachment from sites of capitalist production, Hancox contended, “deliverance from wage slavery” depended upon the mobilization of “mothers, sisters and wives.” A radical maternalism informed her appeals to women to “bestir yourselves for your children’s sake,” but, as her advocacy on behalf of female wage labourers indicates, she never conceived of motherhood as the only legitimate female occupation. Instead, she expanded the emotive and physical bonds women felt toward their blood relations to encompass the “big human family” in ways that unsettled the moral and affectual cultural practices of liberal capitalism. She called on mothers to show courage and organization; otherwise, she warned, “our children will curse us for cowards, if we do not move to protect them, ourselves, and our class, against the onslaughts of Capital.”55

Marriage did not insulate working-class women from the hardships of poverty. For this reason, Hancox never parroted the male-breadwinner discourse that argued married women should not compete on the job market; in fact, necessity drove many wives to waged labour. Nor did the private lives of married mothers evade the humiliations and investigations of charities and relief providers. Hancox revealed how mothers of large families were unfairly shamed because municipal relief only provided allowances for up to three children. In her casework, she defended mothers forced into overcrowded and dilapidated housing. She noted the irony of social workers preaching “hygiene,” for, on such miserly relief rates, “how can the poor practice it?” In 1922, she reported that relief investigators were interrogating married women and if those women failed to measure up as “good managers” of household expenses they were separated from their husbands and forced into “the home of the friendless.” Hancox alleged that the administrators of these institutions had stymied the passing of a provincial Children’s Welfare Bill that would have promoted the home over institutional care, solely to protect their salaries and further undermine the agency of low-income mothers. It was not the poor mothers’ homes that should be investigated but these charitable institutions, charged Hancox. In 1924, she criticized city welfare investigators who compelled wives with no small children to undergo medical exams to determine whether they were fit for employment. Hancox recognized that the desire for mothers to keep their families together, and to protect themselves from slander and unwarranted invasion of their personal lives, served as provocation for collective action. The indignities experienced by impoverished parents lent proof to her assertion that, in Winnipeg, “wealth is of far more importance than childhood and pure motherhood.”56

While the organization of young single workless men dominated the attention of unemployment movements during the 1920s, Hancox also appealed for better conditions for the elderly. She cried, “Shame on you!!” to those who argued that workers should be blamed for failing to “make provision for old age” and who “know full well that workers’ wages” were far too inadequate “to make provision for old age, sickness, misfortune, etc.” One plank of Hancox’s 1923 electoral platform promised to “establish proper care for the aged, not degradation and insult.” After a 60-year-old long-time Winnipeg resident was labelled a “malingerer,” and a policeman confiscated his cane and forced him to labour in the woodyard for his relief, Hancox came to his defence. When the City of Winnipeg fired several elderly men after acquiring new street-cleaning machinery, Hancox led a delegation of street cleaners to city hall. Although the laid-off workers had ten to twenty years’ working experience, most had no savings. They had been thrown away “like old scrap,” she charged, and the aged among them “forced from their families and sent to the Old Folks’ home.” Hancox’s affective labour expanded the purview of radical unemployment politics to all ages.57

Hancox believed nothing incited a mother’s wrath more than the mistreatment of children and youth. Her disenchantment with the Salvation Army led to lurid accusations of its exploitation of the young. Calling Army officers “slave traders” and “dope peddlers,” who indoctrinated children with the adage “servants obey your masters,” she lambasted the organization’s recruitment schemes in which poor youth were shipped from England to Canada and Australia to labour as farmhands and domestic servants. These children were indentured to farmers and households until they paid off the costs incurred for their clothing, transportation, and minimal training. The Salvation Army disciplined the boys to become “workers” and as “cannon-fodder” to “protect private property,” charged Hancox. Its concerns for poor young girls were equally self-serving. The Army, she contended, needed a steady stream of impoverished young women “forced to sell their bodies” to necessitate funding drives for the maintenance of its homes for “wayward girls,” where inmates were locked in their rooms and treated as “criminals.”58

Children were the human collateral of relief officials who refused aid and who showed no sympathy to those of “different flesh and blood.” In 1927, Hancox placed the death of Ray Elliott, a three-year-old child, on the conscience of the “heartless, brutal and callous” swc, which had denied the family assistance and was processing their eviction. Ray had burned to death when his clothes caught fire from the kitchen stove while his mother sought the charitable intervention of Liberal and Métis MPP Edith Rogers. Child labour was also a cause for concern. In 1922, Hancox supported the obu’s organization of newsboys. That same year, after four young men were sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for evading work, she and allies successfully halted the practice of Winnipeg welfare authorities forcing those under 21 to choose between jail or labouring in remote logging camps. Protecting youth, to this radical working-class mother, meant shielding all children from rapacious employers, relief authorities, and a legal system that afforded them little protection or sympathy.59

In Hancox’s estimation, the Canadian courts offered working-class youth neither justice as victims nor mercy as offenders. “There is undisputable evidence that the law functions only for those that possess. … [C]hildren are tortured, our girls are outraged, [and] our boys are driven to crime, for the laws of ‘Private Property,’” she pronounced. Hancox weighed in on the punishment meted out to fourteen-year-old William Bodner in 1924. Bodner was handed a three-year sentence plus lashes for his participation in the so-called Moggey gang. That summer, nineteen-year-old Percy Moggey, an escaped convict, had led a crew of poor working-class youth, some as young as eleven, on a criminal spree that included boxcar thefts, holdups, and burglaries before he was apprehended in a Winnipeg shootout in which two detectives were injured. Bodner, Hancox suggested, was, like so many impoverished youths, “crushed under the mill of Master Class dominance and brutality”; having been “denied a dog’s chance to live,” she reasoned, it is understandable that boys like Bodner may err and “dare to take something that they want.” Instead of sentencing a child to an adult penitentiary, the courts ought to have “free[d] one small boy from the clutches of prison doom and give[n] him a chance in life.” Prison, as Hancox had anticipated, proved no corrective for Bodner or Moggey. Referencing the infamous and contemporaneous US trial of Leopold and Loeb, the wealthy and “degenerate” youth who believed they could murder with impunity (they ended up serving time but avoided the death sentence), Hancox insisted that it was unjust that the “Boss Class can steal, murder and rape and as long as they have enough of the Almighty Dollar they can get away with it,” while the Moggey child gang’s acts of economic desperation felt the full force of the law. She situated the criminalization of youth within the context of economic oppression.60

Hancox’s expansive view of the dispossessed included not just single women, mothers, the aged, and the young but also recent immigrants, regardless of ethnicity. She believed capitalist/state collusion on immigration policy, not immigrants, created poverty conditions. The newcomer’s struggle for existence, she insisted, was the concern of the entire working class. On numerous occasions, she defended impoverished settlers in front of immigration officials and all levels of government. She was highly critical that Winnipeg, like so many other cities, refused relief to anyone who had not resided in the city for at least six months. The migrants who “build up the west should be regarded as citizens,” she maintained, and “immigration should and would be alright … if the workers that procured the food we need were given their just rewards instead of being robbed by those who own the wealth and the land.” However, so long as capitalist and imperialist concerns determine immigration policy, “conditions will not be such as to warrant emigrants coming to this country or those who are here to remain in it.” Hancox warned European migrants that Canada “is not ‘a land flowing with milk and honey’” and challenged the complicity of big business and government in oversupplying the labour market, while refusing to blame recent arrivals for exacerbating the postwar recession.61

Between 1923 and 1925, Hancox exposed the machinations of the Canada Colonization Association, a conglomeration of railway magnates and business leaders who were lobbying Ottawa to ease immigration restrictions and give them the power to rubberstamp immigrants; these immigrants could then fill often-fictitious jobs created by the railway corporations or take temporary positions that were falsely advertised as full-time, year-round employment. Not only did the railways stand to benefit, Hancox wrote, but also the “land-sharks” and mortgage companies who would keep the immigrants, who intended to settle on farms after the railway work dried up, hopelessly in debt. Her warning – that the “optimistic boob” immigrants who “believe the fairy tales” of the association’s advertisements were destined to join the country’s dispossessed – proved prophetic. In 1925, Prime Minister Mackenzie King ceded to the association’s requests and passed the Railways Act. Over the next six years approximately 185,000 workers arrived in Canada to ensure the railways “a steady supply of cheap foreign workers.” These newcomers displaced earlier waves of immigrant workers, increasing unemployment and creating a pool of desperate workers easily cajoled into strikebreaking.62

Hancox also fought the imperial collusion to exploit surplus labour through her work with migrant harvesters. In 1923 (and again in 1928) the Canadian and British state promoted the Dominion as one element of a global “lightening” strategy to relieve Commonwealth unemployment by redirecting British workless to the “bread basket of the world.” Those known as British harvesters did not travel voluntarily but were told that if they failed to apply they would forfeit their rights to relief. The majority were married, war wounded, and lacked any farm experience. Problems began as soon as the almost 12,000 British harvesters arrived in August 1923. Many were forced to panhandle. Others, sent out to farms, dropped their tools after discovering that their bosses, reneging on the promised four dollars per day, were “stingy, tough, impatient and demanding.” Wages were often as low as two dollars a day. Many farmers simply refused to hire them. Hancox was among the leading activists who organized harvester demonstrations and wrote formal appeals for help to labour organizations and all levels of government. “It is not the fault of these men that they are in such a plight, but rather of this deplorable system followed in placing harvest help,” she wrote. Nothing less than union wages or free transportation back to England, she told a crowd of harvesters, would quell the unrest. The immigration department agreed, following protests by Hancox and the Manitoba Association of Unemployed, to offer reduced rail fares to those seeking industrial jobs in central Canada. Over 1,700 men rode east. Hancox denounced Winnipeg for cutting British harvesters, now dubbed “transients,” from relief in December, but she considered their agitation to secure transportation east a victory. Upwards of 20 per cent of the 12,000 harvesters were deported or voluntarily returned to Europe. Hard times lay ahead for harvesters once the grain was threshed and stored. Hancox reported the story of Willie Jones, a nineteen-year-old British harvester who, penniless after the excursion, buried himself in a haystack for thirteen days awaiting death. By the time a farmer found the boy, both of Jones’ feet required amputation owing to frostbite. Hancox admonished the Winnipeg Tribune for stating that the boy ought to have reported himself to immigration to receive a free deportation, as she believed it was more likely he would have been jailed as a vagrant.63

Hancox believed other immigrants were as deserving as the British harvesters. When she argued for more generous welfare “so that we can rear a strong, healthy race,” she spoke of “race” in its universality – or as one “big human family” – and not in terms of a hierarchical and essentialized typology that placed white Anglo-Canadians above other ethnicities. A familiar face in poor immigrant communities, Hancox regularly shared the stage with left-wing Russian, German, Hungarian, and Ukrainian activists. She appeared at a “peasant ball” in 1922 to raise money for the Russian Famine Relief Fund. In her casework, she frequently defended the non-Anglo ethnicities among the dispossessed. She appeared at several mass meetings of the unemployed in the Ukrainian Labour Temple and supported ethnic organizations that shared a critique of capitalism. In 1924, when the Citizens lobbied the Department of Justice to shut down the temple for its supposedly seditious activities, Hancox reminded the Anglo-Canadian readers of the Worker that, should this “secret Fascisti organization in Winnipeg subdue these comrades, then they will go on to beat into subjection every other workers’ organization that is trying to gain for the workers their rights and privileges.” Her affectual and antiracist appeal urged all workers, for their “own preservation,” to protest the “attack [on] our Ukrainian comrades” and to “not let prejudice, envy, hatred or malice keep us apart.”64

Edith Hancox with Ukrainian family, circa 1920s.

From the private collection of Edith Danna.

That same year, Hancox scored E. E. Hutchins, president of the Great West Saddlery Company, for proposing the importation of “coolies from China” under slave contracts to ensure “economic stability” and a cheaper labour pool in the country. “If Mr. Hutchins would read,” she quipped, he would realize that slavery leads only to societal “destruction” and that the only way to “right the whole world, Canada included,” is by placing “human rights before property rights.” Hancox also spoke out about the global oppression of workers. In 1925, aligning herself with insurrectionary Indian nationalists, she dismissed Britain’s rationale that seditious activities and Hindu-Muslim animosity necessitated the continuance of colonial rule. India’s peoples should rule themselves, she believed. Britain betrayed its paternalistic promise of “sincerity,” “goodwill,” and “cooperation” by its continued exploitation of India’s workers, including thousands of women and children who laboured in imperialist-run mines. “Today the master class get as much fun from watching the working class of one country fighting and killing the working class of another country as they did in the ancient [times] when the gladiators and beasts fought in the arena,” she wrote. Only international working-class solidarity could “throw off the imperialist and Capitalist sharks that forever fool us.”65 Hancox recognized the British subjugation of India, but, like many other radicals of her era, she overlooked the impacts of colonization on the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island.

Conclusion

In 1928, during the transition into the Comintern’s “Third Period” wherein the party abandoned collaboration with other leftists, the cpc sent William McEwen to Winnipeg to weed out those who failed to toe the party line. At renewed unemployment protests that spring, McEwen monopolized the limelight at the 3,000-strong gatherings and demoted Hancox to clerical work, in spite of her continued reverence among the workless masses. Soon after, Hancox retired from activism. Both the Communists’ Third Period turn and McEwen’s patriarchal dictates undoubtedly factored into her departure. In the fractured climate of the Third Period, and with the untimely death of Florence Custance in 1929, the cpc largely ignored and discouraged the contributions of rank-and-file women. The cpc leadership, with few exceptions, derided the wlls as reformist and deemed feminism a divisive distraction from class struggle. If that was not enough to rankle Hancox, the cpc, by rejecting any kind of United Front tactics, made irrelevant exactly the kind of organizing she excelled at.66

Personal reasons also factored into Hancox’s abrupt withdrawal from radical politics. Emotional burnout came as a side effect of almost a decade of fighting losing battles. Declining health and cataracts limited her mobility and sight. In addition, financial instability disrupted her devotion to the dispossessed. In September 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, Hancox defaulted on her mortgage and lost her business, home, and organizing base. Her husband, who had supplemented Chamberlain & Co.’s earnings as a handyman at the Brookside Cemetery, managed to secure work as a night watchman at a municipal hydroelectric station. Through the 1930s, when Winnipeg’s unemployed could have benefitted from her organizing acumen, Hancox and her family moved from apartment to apartment. Instead of promoting revolution, she sold illegal Irish Sweepstakes tickets and worked a concession stand at the Assiniboine Downs. Collective hopes had disintegrated into working-class escapism. Gardening, games of chance, and family gatherings occupied the time she had once spent organizing the unemployed. Hancox died on 3 June 1954, 35 years after she first shone on the Victoria Park stage, her radical leadership all but forgotten.67

Edith Hancox, late 1920s.

From the private collection of Edith Danna.

For Hancox, who came of age during the rise of industrial capitalism, the tribulations afflicting an illegitimate child, a young servant, working-class mother, and immigrant were the hegemonic means that structured her feelings, if not her consent. Although she became a freed “wage slave,” as a business owner, poverty, debt, and shared cultural practices kept her organically tied to her working-class origins. Religion provided a platform for Hancox to assert her independence before she rejected its transcendence in favour of a socialist millennialism. The Winnipeg General Strike portended the revolution, but only, she argued, if the people escalated their defiance against racism, sexism, and capitalism. In postwar Winnipeg, exploitation of workers at the point of production made labour unions a necessity; for Hancox, unemployment, hunger, and want required different, complementary, but no less important, militant organization. Political and union representation, she insisted, were no substitutes to the mobilization and empowerment of the dispossessed. Hancox’s indignation and empathy derived not only from personal economic hardship but also from the sexism she experienced from allies and adversaries alike. Although she espoused a radical motherhood, her feminism cannot be reduced to the maternal or the protective; she personally rebelled against her gendered roles as a mother and a wife, encouraged children to be frontline activists, and refused to measure a working-class woman’s value by her reproductive capabilities. Believing that we are strongest when we recognize, support, and ally with those whose oppressions are not our own, Hancox’s homespun socialism extended the struggle for equality and justice across genders, generations, ethnicities, and borders. She realized that to build a movement we need to respect the emotions of ordinary and diverse peoples. Her affective contributions suggest that appealing to rational self-interest or decency does not make for revolution, but rather, how a racist capitalist patriarchy makes us feel is the basis of solidarity and the material of resistance.

Hancox’s historical erasure originates in the undervaluing of unpaid community organizing compared with the remunerated union official or political functionary. Her labour of love has been obscured by the left’s inconsistent appreciation of “women’s work” and “emotional labour,” on the one hand, and by the perception that the politics of the dispossessed matters less than the agency of those who produce, on the other. Gender and class discrimination constrained Hancox’s activism. Yet, paradoxically, her affective contributions arose from the distinctive insults, immiserization, and exclusions experienced by women and the workless, and it was at the confluence of these overlapping oppressions where her impact was felt most strongly.