Labour / Le Travail

Issue 85 (2020)

Research note / Note de recherche

Casinos and Captive Labour Markets: The Case of Casino Windsor

Casinos are emblematic of a strategy to create low-skilled service jobs in economically depressed cities. States and provinces encourage casino developments based on the ability of these facilities not only to create jobs but to provide “good jobs” (i.e. with high wages, benefits, and job protections) in host communities. Existing research offers competing scenarios of what casinos mean for workers in these host communities. Some scholars find that workers benefit from casinos via employment and wage growth.1 Others find that casinos exploit host communities, including their workers.2 While little research focuses specifically on the quality of casino jobs, some scholars suggest that the compensation and conditions of casino employment may decline as the casino gaming environment becomes more competitive.3 However, research also identifies two caveats concerning the ability of casino workers to cope with work-quality decline: first, casino employment tends to attract those who treat the work as temporary and/or supplementary work; and second, workers are free to seek employment at other casinos – casinos being a growing industry – and to “chase tips” if they are unhappy with their working conditions or remuneration.4

Unlike previous research, which focuses on geographic areas with multiple casinos, such as Las Vegas and Atlantic City, the purpose of this article is to understand whether and how casinos provide “good jobs” in locales where casinos are increasingly being used as an economic revitalization tool – that is, in deindustrializing settings – and with a single operator in a region. I examine the case of Casino Windsor, a unionized casino in a peripheral gaming market – Detroit-Windsor – in Windsor, Ontario, which is one of Canada’s former automotive capitals. To enrich understandings of whether casinos provide “good jobs” over time, the findings in this study suggest that Casino Windsor initially offered workers with employment histories in the low-wage service sector the prospect of higher compensation and union representation. In interviews conducted in 2014 and 2015, employees shared how Casino Windsor provided them the ability to pursue a higher standard of living. These workers also highlighted that Casino Windsor represented an opportunity, particularly for women, in the female-dominated service sector (60:40 female to male). For these workers, the tips, wages, benefit packages, and union representation meant that employment at Casino Windsor represented upward economic mobility.

Their experience of economic mobility, however, was short lived, spanning from 1994 (when the casino opened) to 2000. The decline of Casino Windsor’s revenues coincided with the establishment of three casinos across the US-Canada border in Detroit. As casino competition increased, remuneration and working conditions at Casino Windsor deteriorated. Tips declined and wages stagnated. Casino management also streamlined its labour costs by laying off workers, relying on a more flexible workforce, and outsourcing venue space to non-union corporations. In addition, workers also reported that management’s disciplinary action against employees has increased as revenues and visitation have declined. In fact, during the 2004 round of collective bargaining, Casino Windsor workers went on strike for “respect” – something they felt they were losing in their interactions with management. They insisted that the strike was about “respect” rather than simply wages. Among their grievances were the increase in management’s disciplinary action against them and insinuations by management to workers that they were not only replaceable but unlikely to find comparable compensation elsewhere. Despite these tactics, Casino Windsor workers remain (turnover is low) and have internalized the importance of providing quality customer service.5 Casino employees treat their provision of quality customer service as essential to keeping Casino Windsor competitive and open for business.

These findings provide an alternative story of the employment implications of casino development when the workers themselves are not mobile. Immobility allows management to rule through disciplinary actions while still reaping the benefits of worker “loyalty” and effort. Casino Windsor workers have little choice other than to offer good service to keep their jobs. In theory, they are “free” to go elsewhere, but in fact, there is nowhere else to go. With Windsor on an international border, with the city’s long-standing high unemployment rate, and with no other employer in the low-skill service sector in the region providing comparable remuneration, Casino Windsor has created a company town where workers are captive and feel that their provision of customer service keeps the casino open and competitive. I argue that local economic conditions and specific Casino Windsor management practices have created and benefit from a captive labour force.6 I further argue that workers, by providing high-quality service, reclaim their sense of worth and mitigate their sense of precarity.7 Workers say that they do not feel valued, respected, or appreciated by management but that they should be because, in their view, they are “the best.”

These findings raise questions concerning the labour markets into which casino developments – which are state sponsored and are legitimized to host communities as creators of “good jobs” – are placed. American states and Canadian provinces are increasingly using casinos as an economic revitalization and job creation strategy in economically depressed regions, tending to locate them in areas that lack other industries. This strategy has now spread across the globe, especially on state/provincial and international borders where governments attempt to (re)capture gambling dollars.8 I argue that researchers and policymakers must consider whether such developments will create and potentially exploit captive workers, leading to declining job quality. These findings speak to what casinos mean for workers when placed on an international border and attempting to cope with deindustrialization.

In mapping out these arguments, I first lay out conceptualizations of “good” and “bad” jobs. I then discuss the rise of the service sector in relation to the spread of casinos as “good job” creators and describe how this case contributes to understanding whether and how casino workers experience casinos as generating “good jobs.” I then discuss in detail how Casino Windsor was initially an economic opportunity for low-skilled employees in the service sector. I examine how workers experience what was initially an economic opportunity as financial hardship while their employment has become increasingly precarious. I point principally to the immobility and captive status of Casino Windsor workers to explain why these workers do not leave or “chase tips,” as previous scholarship has demonstrated. Finally, I show how workers cope with their immobility and management’s negation of their worth by laying claim to the idea that they are responsible for the continued existence and success of Casino Windsor.

“Good” and “Bad” Jobs

Precarious employment – or “bad jobs” – differs from the full-time, benefitted, well-paid, and open-ended contracts – or “good jobs” – associated with the blue- or white-collar single-earner male worker of the Fordist economy.9 Precarious employment also stands in stark contrast to the rewards earned by high-skilled knowledge workers of the “knowledge economy.”10 Precarious employment can be broadly understood in terms of risks associated with and quality of employment. Precarious work is the experience of uncertainty resulting from one’s employment, whether in the form of income, employment duration, or lack of control over the labour process. Wide-ranging definitions of precarious employment exist. For instance, Steven Blondin, George Lemieux, and Lauren Fournier describe precarious employment as involuntary, nonstandard work, while others define it as unstable, unprotected work that pays poorly and offers little hope for the future.11 Others suggest that precarious work is temporary, presents uncertain work situations that prevent people from planning their future careers, and possibly provokes psychological distress and negatively impacts health outcomes.12 These definitions suggest that precarious work is low-quality employment that lacks multidimensional labour security and places workers at different degrees of risk.13 Other scholars argue that, while the extent of precarity exists on a continuum, all workers are in fact part of the “precariat” because of their dependence on wage labour.14

Precarious employment as a concept embraces the full range of attributes associated with job quality and the degrees to which quality can be threatened, regardless of employment status.15 Income level is critical in determining whether employment is precarious. In fact, a job may be secure on one axis (e.g. stable and long-term) but precarious overall if the wage does not maintain the worker as well as their dependents.16 Ultimately, a primary marker of precarity is insufficient pay, and low pay and employment uncertainty tend to go hand in hand.17 For the purposes of this article, the definition of a “good job” is derived from interviews with 28 casino employees. Like the conceptualizations of precarity discussed above, these workers discussed job quality and the precarity they were experiencing in terms of remuneration, job security, and the “respect” they received from management.

The Rise of the Service Sector, the Spread of Casinos, and “Good Jobs”

With the rising prominence of service-sector employment and the loss of “good jobs” that manufacturing-centred regions once provided, the labour market has become increasingly segmented in terms of the rewards received by high- and low-skilled workers.18 The insecurity that coincides with “postindustrial” employment, particularly for those low in human capital, is in stark contrast to the so-called Keynesian “golden age” of employment opportunities for male-dominated industrial work in the postwar period.19 Relatedly, many employers in the service and hospitality sectors – which are now employing a much greater share of the workforce – offer precarious employment conditions to their workers.20 The difference between the rewards received by low-skilled manufacturing workers and those granted to low-skilled service workers is largely attributable to differences in sectoral union density.21 Rising income inequality, in large part, is due to the dismantling of unions in the private sector that formerly insulated a large proportion of workers by taking a certain percentage of wages out of market competition. By contrast, contemporary service work represents the “new” economy of non-unionized, low-wage, and non-benefitted work.

Whether a job is considered a “good job” depends on the relative economic position of the workforce being addressed. Policymakers have readily characterized casino employment as providing “good jobs” for low-skilled workers.22 Policymakers have come to this conclusion because casino jobs tend to be defined by good wages (compared with those of other low-skilled service and hospitality jobs), the ability to make tips, and relative job security (from working for a large employer). Also, across North America, casino employment is highly unionized compared with the broader service sector. When unionized, casino jobs will more likely be “good jobs” because they offer higher wages, benefits, and job security.

The promise of growing employment and bringing quality jobs to economically depressed areas drives casino development.23 Indeed, many low- and middle-income communities across North America have adopted casinos as both an economic development strategy and a job creator.24 In economically struggling Windsor, purveyors of casino development emphasized the promise that Casino Windsor would bring “good jobs.”25 Scholars focusing on the economic impacts of casinos have debated whether casinos have a net effect on an area’s unemployment and wages.26 Thomas Garrett finds employment growth in counties with a casino compared to counties with no casino; similarly, Daniel Monchuk finds casinos to have a positive effect on employment while decreasing the unemployment rate.27 Chad Cotti suggests that casino introduction increases aggregate employment and has positive wage effects in host counties relative to counties without a casino.28 Studies examining the impacts of casinos in Indigenous communities in Canada and the United States have found gains in terms of employment and income.29 Some also argue that the employment and wage gains (if any) tend to be limited and may plateau or decrease over time. For instance, Gerald Hunter finds that casino employment effects – defined as employment growth – were positive and significant only for new casinos.30

Other scholars suggest that casinos are less economically helpful for host communities and are politically fraught developments.31 According to Dean Gerstein et al., casinos have no significant per capita income effect.32 Using a case study of Chester, Pennsylvania, Christopher Mele argues that casino development isolates the city from other forms of investment while representing one facet of the aggressive push by states/provinces and local governments to attract private capital.33 Lisa Calvano and Lynne Andersson examine casino legalization in Philadelphia and the conflict created between the community, on one side, and the gaming industry, investors, and real estate interests, on the other. They argue that the Philadelphia case represents government and corporate elites extracting value from already low-income and/or downwardly mobile citizens.34 Effectively, this literature tends to critique casino development, suggesting that it hinders rather than helps host communities and their citizens.35 However, with their focus on high-powered stakeholders and interest groups, these studies rarely mention workers. In fact, if mentioned at all, workers are framed as a disenfranchised group amid larger struggles over resources. Despite arguments that casinos further devitalize and exploit economically depressed areas, few studies actually speak with or study casino employees – the group that is supposed to benefit directly from the casino – to understand how they experience this “revitalization” effort.

Research that specifically addresses whom casinos employ and how workers experience the quality of employment is sparse, but a few notable ethnographic studies are working to fill this gap. Jeffrey Sallaz, for instance, examines the labour process of blackjack dealing and how the presence of clients at the point of production, in tandem with the tipping relationship, affects managerial strategies for organizing and monitoring workers. Sallaz suggests that the tipping relationship in Las Vegas creates a semblance of agency and entrepreneurialism for dealers as they “hustle” players for tips, and he argues that this entrepreneurial game diffuses overt conflict between managers and workers. Dealers blame their low wages on customers who tip poorly, while potential anger over their lack of job security is mitigated by their frequent lateral movement across firms (to “chase tips”). Sallaz’s focus remains quite narrow, however, applying primarily to dealers and the tipping relationship.36

Chloe Taft’s 2016 ethnography, From Steel to Slots: Casino Capitalism in the Postindustrial City, puts little focus on casino workers but offers a squarely negative assessment of casinos and the employment they offer.37 Taft suggests that casino workers are complicit in their precarity, embracing the postindustrial mantra of individualism and entrepreneurialism. Taft, like Sallaz, discusses how casino workers have a sense of mobility, as they can “chase tips” and move to different casino employers in the region if dissatisfied. Similar to Sallaz, Taft focuses mainly on dealers while suggesting that casino employees do not have a sense of long-term commitment to their employer. Ellen Mutari and Deborah Figart focus on changes in job quality in Atlantic City casinos. They find that job quality has deteriorated, which they attribute to the increasing saturation of the casino market and the short-term demands of shareholders that increasingly dictate workplace conditions. Cost-cutting measures have displaced the goal of creating “good jobs.” While moving to more flexible employment relations, some casino workers are making casino work a temporary pursuit.38 Workers also use their mobility to work at other casinos in the area to cope with declining conditions, loss of hours, or job loss.

This research suggests mixed findings regarding whether casinos provide “good” or “bad” jobs, with a limited focus on how this can shift over time. As a highly unionized industry, casino employment tends to offer higher pay than is found in other service and hospitality occupations.39 Yet, the few existing ethnographic studies that address the question of job quality are concerned with non-union casinos. And those studies that do address work issues tend to focus on dealers, who tend to be non-unionized even in unionized casinos. Current research is also based on geographic areas considered “casino centres” and on regions with long histories in the service and hospitality sectors. This ethnographic research suggests that casino workers generally do not have a sense of long-term commitment to a single employer and/or can and will seek alternative employment in the casino industry when experiencing unsatisfactory workplace conditions.40 Indeed, little has been said about what casinos mean as employment creators in a deindustrializing setting and in peripheral casino locations. How do casino workers experience this job-generating strategy and cope with the potential changes to employment quality when experiencing mobility constraints in an increasingly competitive gaming market? I use Casino Windsor, a unionized casino in the peripheral gaming market of Detroit-Windsor, to understand the public policy trend of locating casinos in devitalized – and deindustrializing – settings.

Research Context

Windsor and Detroit are divided by the Detroit River, which also demarcates the US-Canada border. The birthplace of the Canadian automotive industry, Windsor has long been seen as a smaller version of the Motor City, dependent primarily on the Big Three auto companies (Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler) for employment. Windsor’s dependence on the auto industry has made it very similar to a company town.41 Historically, the automotive industry has both served as a key source of Windsor’s tax revenue and been – and continues to be – the main employer of Windsorites.42 With automotive workers heavily unionized, the automotive industry in Windsor served for much of the twentieth century as a proven source of “good jobs” for many low-skilled workers. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, a deep recession heavily impacted Ontario’s manufacturing sector and hit Windsor’s automotive industry especially hard.43 The recession, coupled with angst about the implications of the soon-to-be-signed nafta agreement – specifically, that manufacturing jobs would be leaving the city – worked to provoke concerns about Windsor’s heavy reliance on the automotive industry. Talk of diversifying the local economy via casino development began.44 In 1993, the provincial government chose Windsor to host the first casino in Ontario as a pilot project. Given that Windsor was the first trial site for casino development in Ontario, the city provides an opportunity to examine the sort of jobs casinos provide over the long term. Casino Windsor was also one of the first resort casinos to be developed in North America outside of Atlantic City and Nevada. For a period of time, it was even the “highest-grossing casino in the world, per square foot.”45

Methodology

The findings presented below are based on 48 semistructured interviews with Windsor stakeholders from politics, business, and labour and Casino Windsor employees, as well as local news content from the Windsor Star (published between 1994 and 2015) and descriptive statistics.46 Interviews were conducted from September 2014 to April 2015. I questioned 28 casino workers on their personal and employment histories and 20 local stakeholders on the sort of jobs the casino has created in the community. Interviews lasted from one to three hours.47 While there was a set of primary questions, interview guides were specifically crafted for each individual. For the stakeholders, I called and/or emailed their respective offices and requested interviews; the interviews were then conducted at their place of work or at a coffee shop.

In contrast, obtaining interview participation from casino workers was a difficult undertaking. As mandated by Casino Windsor, workers are banned from speaking to media or researchers about Casino Windsor and their employment. I had been unaware of this nondisclosure agreement prior to entering the field since this information is not publicly available. I began recruitment by placing flyers on approximately 110 cars of casino workers in the casino’s parking garage. Not receiving a single call, I discussed this recruitment failure with a Windsor relative. She told me of a friend who was a casino worker who lived nearby, suggesting that I approach her at her home. Going to this woman’s home, I asked if she would be willing to participate with full confidentiality. She quickly declined, explaining that she could not risk losing her job. Ultimately, the casino employees were inaccessible through direct recruitment due to fear of termination. I then requested access through the casino’s human resources department, which was denied. I reached out to the union representing the casino workers, Canadian Auto Workers/Unifor Local 444; the union proposed that I conduct focus groups in the presence of a union representative on-site at the casino with permission from the employer.48 Again, management denied this request. I then attended a union hall meeting where I was introduced to members. At that meeting, the union president assured members of confidentiality, enabling me to obtain a sample of 28 casino workers.

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. I took notes during interviews with some of the casino workers because they offered additional information on their workplace experience that they were not willing to share on tape. Using maxqda 12 software, I used an abductive approach to analyze the data, employing rigorous data analysis against the backdrop of expertise in the various literatures related to casino development.49

The Casino Windsor employees recruited at a union hall meeting represent a self-selected sample in that I did not approach them directly at the meeting. Casino workers who attend union hall meetings are likely not representative of the general population of Casino Windsor workers. Therefore, the casino workers represented in this sample may be more likely to be critical of the employer and/or more disposed to express workplace grievances than the broader population of Casino Windsor employees. To respect the confidentiality of the participating casino workers, I gave each interviewee a pseudonym; also, I do not identify the position each worker holds, because they sincerely feared termination if management were to learn of their participation in an interview. Five of the Casino Windsor workers at the time of their interview were working in back-of-house positions and 23 were working in front-of-house positions. Of the sample, 17 identified as female and 11 identified as male.

Finally, I surveyed the local newspaper, the Windsor Star – Windsor’s only major daily newspaper – for content published from 1994 to 2015, which represents the period between when the casino initially opened and when I finished conducting interviews. Using the search terms “casino” and “gamble,” I utilized the Canadian Newsstand online database to find articles containing either word during this period.50 From these articles, I drew out the “official” narrative being produced in the city in real time. This offered a further backdrop with respect to whether and how Casino Windsor has offered “good jobs” in the community.

Windsor’s “Windfall” (1994–2000): The Casino and Its Promise of “Good Jobs”

When the casino opened in Windsor, employment in the facility offered an economic opportunity for the city’s workforce. Many of Casino Windsor’s workers were previously employed in the low-wage service sector. In contrast to the expectation that the signing of nafta would result in dramatic job losses in Windsor’s automotive industry – indeed, the motivating force behind the local drive to acquire a casino – the auto industry experienced a boom in the mid- to late 1990s brought on by surging demand in the United States for new vehicles. During this period, the automotive industry in Windsor employed more people than it ever had previously.51 Indeed, instead of the casino absorbing displaced automotive workers, most who took up casino jobs came from Windsor’s service sector. As evidenced below, the casino represented not downward economic mobility – which would be the case for the displaced (largely male) auto worker, whose annual income was approximately $75,000 in 2015 while a Casino Windsor worker’s annual income was approximately $42,000 in 2015 – but rather upward economic mobility for those already in the (largely female) service sector.

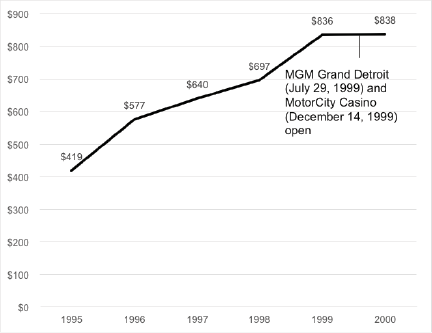

Figure 1. Gaming Revenue (millions) of Casino Windsor, 1995–2000

Source: Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation (OLG), “Casino Windsor Annual Gross Revenue for 1994–2014,” 18 April 2015, obtained through a Freedom of Information request to the OLG.

Casino Windsor was the only casino in the region from 1994 until the late 1990s. Casino worker interviewees recalled this period of market monopoly: Isabelle nostalgically remembered “being the only game in town,” for example, echoing Catherine’s contention that patrons were “literally lined up all the way around the building to come in.” The casino’s initial success resulted in an increase in income for its employees, as a combination of base wages and tips. Linking their remuneration to the casino’s success, workers like Anne frequently pointed out that “we were making money hand over fist” (see Figure 1).

With employment histories in low-wage service employment, casino workers reported that the base wage alone was an “opportunity” when the casino opened. Many casino workers affirmed that, when taking up employment at the casino in the early and late 1990s, they experienced a $3 to $4 increase in their hourly wage. The average hourly wage at the casino in 1994 was $9.32.52 The first collective agreement was signed in 1995; by 1998, the average wage had risen to $11.67 an hour. After the second collective agreement, in 1998, the average wage rose again, to $13.59 in 2001. In contrast, the Ontario provincial minimum wage was $6.85 during this period (until 2004). Karl discussed the relative increase in compensation when first hired by the casino, saying, “I was like ‘$13 an hour!? Oh my God!’ There were cheques like I’ve never seen before.” In fact, many workers saw the casino as the only place besides the automotive industry to make a decent wage as a low-skilled worker in the area.

The casino’s initial success (between 1994 and 2000) resulted in lucrative tips, or what workers call “tokes.” When tips were accounted for, and after the caw negotiated the first collective agreement in 1995, Casino Windsor employment was considered among the most lucrative in the city. For instance, the Windsor Star reported in 1996 that Casino Windsor dealers earned an annual income anywhere from $50,000 to $60,000, which was “believed to be the highest in the North American [casino] industry.”53 A 1998 item in the newspaper rhetorically queried,

What’s the most coveted job in Windsor? Research scientist? Corporate ceo? Brain surgeon? Try none of the above. Not to sneeze at any of these prestigious career choices, but the job that folks around this city would kill for right now is the bellhop position at Casino Windsor’s four-star hotel that’s opening next month. Would you believe up to $60,000 annually, most of it in tips, for sweet-talking the big players and delivering luggage to their complimentary rooms?54

The casino also offered union representation. All but one worker I interviewed were previously employed in non-union workplaces. Workers discussed the advantage of being unionized in the service sector and the job protections not found in their previous workplaces. Workers also enjoy health benefit packages through their union membership, which is rare in other low-skill service jobs. For full-time casino employees, benefits currently include life insurance of $60,000, a prescription drug plan, semi-private hospital coverage, medical and health practitioner coverage, and vision, dental, and orthodontics coverage.55

Opportunity for Women (and Men)

While the casino pulled in both male and female workers, the broader low-wage service sector tends to be female dominated.56 Casino Windsor workers and Windsor stakeholders see the casino as offering an economic opportunity, especially for women. In 1994, the other large industry in the city that offered a high wage was automotive manufacturing. This workforce, however, was estimated to be about 95 per cent male, and, in 2015 at the Chrysler assembly plant, females fell within the 26 per cent of the workforce considered to be a “visible minority.” In contrast, in 2015, women comprised 61 per cent of the casino workforce, or 1,351 of the 2,224 unionized workers.57

Many casino employees recognize the gendered composition of the casino’s workforce and the favourability of such work for women. As Heather stated, “For what is traditional female employment, we are the highest paid.” She went on to say,

As a workplace, it has probably benefitted a lot of women because we are predominately a woman workforce. Like, a guestroom attendant will make a lot more money there [at the casino] than they would at the Holiday Inn or at some of the independents. … Like I said, look at what cashiers are making anywhere else or even as a bank teller, because a lot of casino cashiers that work in the [cash] cage came from the banking industry. And they are making way more money than they ever would at a bank.

Karen stated that women in the city have progressed economically because of casino employment, which has allowed them to be more “independent.” Patty echoed this sentiment: “It gave women a decent-paying job. … So, it gave a huge option for women. … If anything, it gave us money of our own, a decent wage, and benefits.”

Casino workers also emphasize that the casino offers single mothers the ability to provide for their dependents. Samantha, a single mother who previously worked in the fast-food industry, stated,

Some women that possibly wouldn’t have been making or getting the benefits, I mean myself included … because honestly a single mother raising her child, your […] especially without postsecondary or anything like that, you are not really in a position for a $20 an hour job, with benefits, you know. The casino did give that to me. The guys I guess, twenty years ago had more opportunity to make that kind of money with auto, they don’t now […] but they did.58

As Samantha implies, the unionized automotive sector functioned to provide good wages largely for men. In contrast, the unionized casino has functioned to provide relatively higher wages for a female majority of service workers.

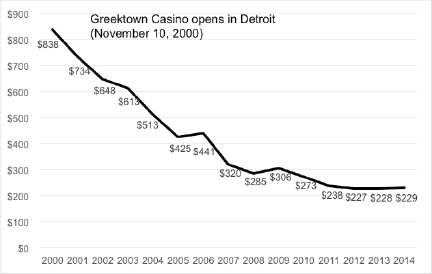

Figure 2. Gaming Revenue (millions) of Casino Windsor, 2000–14

Source: olg, “Casino Windsor Annual Gross Revenue for 1994–2014,” 18 April 2015, obtained through a Freedom of Information request to the OLG.

The casino also offered an opportunity to men in Windsor who were previously “stuck” in low-wage jobs in the service sector. In my sample, these men typically came from low-wage and non-union employment in bartending, bouncing, contract security, grocery stores, and restaurants. Casino worker interviewees, however, did not explicitly discuss how the casino offered an opportunity to low-skilled men coming from the service sector. Regardless, given the employment histories of the male casino workers, casino employment was undoubtedly an opportunity for these men. However, the casino’s rewards and working conditions began to decline once Detroit opened three casinos in 1999 and 2000. Increasing casino competition (along with the Detroit casinos’ competitive advantage of offering free alcohol to gamblers) and a host of other unfavourable factors – what Betty, a Windsor casino worker, described as a “perfect storm”: post-9/11 border security, the closing of the exchange-rate gap (the Canadian dollar was trading at approximately $0.65 during the late 1990s versus $0.99 in 2012), higher gas prices (which particularly impacted the spending patterns of US patrons), and Ontario’s provincial smoking ban (enacted in 2006) all contributed to declining revenues for Casino Windsor.

From Fast Money to Hard Times

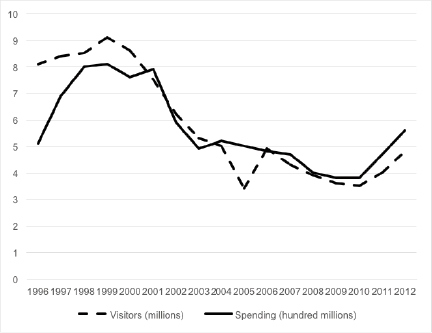

With revenues beginning to decline in the early 2000s, casino workers’ prosperity also declined (see Figure 2). Despite earning a comparatively better wage than workers at other service workplaces in the area, Casino Windsor employees discussed how they and their co-workers now experience financial hardship. In an industry where many workers depend on tips for a good livelihood, shrinking demand has a direct and profound impact on earnings (see Figure 3). As Mike contends, tips are “not as good as they were back in the heyday” and are “inconsistent” in that “some days they come and some days they don’t.” Casino workers feel, as Hank noted, that they have gone “backwards” and, in Diane’s words, are “realistically facing financial hardship.”

Figure 3. Visitors and Visitor Spending in Windsor (Census Metropolitan Area)

Source: Data set provided by interviewee, Tourism Windsor, Essex, and Pelee Island, 2015, in the author’s possession.

a Data release incomplete for 2005.

b Data for 2011 is not a true comparison with other years because of operational and conceptual changes at Tourism Windsor, Essex, and Pelee Island.

During Casino Windsor’s initial years of prosperity, from 1994 to 2000, many casino workers took on the debts of a middle-class lifestyle. As Betty notes, “So, back when I was an assistant manager [of a small store], I made $10 to $11 an hour, we were fine. And then [starting work at the casino] you make more money, you spend more money. The mortgage gets higher, cars get nicer, more toys.” Workers contended that they or their colleagues are now living paycheck to paycheck – what Jim described as “on the lower end of average,” for example, and what Matt characterized as “just above poverty level.” When Casino Windsor operated in a monopolistic gaming market, its workforce – especially those who were tip based – experienced a dramatic increase in income, with the result that workers reported more spending, including taking on larger mortgages and long-term debts. However, as revenues and visitation have declined, so too have the incomes of the workforce as base wages have stagnated and tips have declined. Moving from “boom” to “bust,” these workers now struggle financially to make good on the debts of the middle-class lifestyle they adopted.59

Beyond tips, casino workers’ wage growth has also declined and, at times, wholly stagnated over the years. For instance, in the 1995–98 collective agreement, there were wage gains of 17 to 34 per cent over three years with the average wage increasing by 25 per cent.60 In the 1998–2001 collective agreement, there were wage gains of 16.5 per cent over three years (75 cents in the first year and 50 cents per hour in each of the two following years). In the collective agreement covering 2004 to 2008, wages rose $1.70 over four years (approximately a 42-cent increase, yearly), representing an increase of approximately 11.5 per cent over four years. From 2008 to 2011, there was a two-year wage freeze and a raise of 30 cents per hour in the final year, amounting to approximately a 1.8 per cent increase. In the 2011–14 collective agreement, there was a wage freeze in 2011 and a 25 cents per year increase in the second and third years. This equalled an approximate 2.9 per cent increase. Finally, in 2014, a four-year deal was signed where workers would have a wage freeze in years one and four and raises of 25 cents and 35 cents per hour in 2015 and 2017, respectively. This equals approximately a 3.5 per cent wage increase over four years. Wage gains have consistently declined since the first collective agreement. In interviews, workers discussed this decreasing wage growth, the rising cost of living, and the feeling that they are going “backwards.”

Cutting Labour Costs: Layoffs, Part-Time and Casual Work, and Outsourcing

Casino management has also sought to cut labour costs – with 85 to 90 per cent of its costs being labour based – through layoffs, part-time and casual employment, and outsourcing.61 Mirroring declining revenues, permanent layoffs at the casino began in 2001. Although the workforce grew from 1994 until 2001, there has since been a steady decline, from approximately 5,400 unionized workers in 2001 to 2,200 in 2015.62 Workers report increasing employment insecurity through the years, which Karl characterized as “like a noose tightening.” Because of the minimal difference in years of seniority between workers – a result of few new hires over the last fifteen years – along with continued downsizing, the casino workforce reports both job insecurity and an omnipresent sense of the threat of job loss. Despite her seniority, Sandra, who began working for Casino Windsor in 1995, said, “You are never secure in your job, even with twenty years my job is not secure.” Sara reflected on the “devastating and quick” impact of job loss from the casino: “Because if you are living paycheck to paycheck, within seven days, you know, it’s a huge impact. It would be a quick impact. Not like if you were at the Big Three [auto manufacturers].”

Some workers described the results of job loss from the casino, having known people who lost their cars, homes, and families. They also noted that some casino workers, following job loss, shift from worker to consumer, taking what little money they do have and gambling it away. For instance, Denise stated,

After being laid off they come back, gambling whatever they had left away. And live in their cars and come back. I’ve seen slot attendants make a bazillion in tips, you know, and when they [the casino] decimated their numbers, lose their houses and stuff like that. Because they just lived over their means. … They thought that the bottom would never fall out, they thought that this was going to go on forever and ever.

Jill offered a personal example of being laid off: she had to find employment at a fast-food restaurant where her child happens to be a manager. Jill left the fast-food restaurant, however, because the casino recalled her – though only part time. Jill thought about keeping both jobs but was unable to coordinate the scheduling demands of the two employers. Nonetheless, she remains afraid of being laid off again and having to return to fast-food employment. She is not alone in this; several casino workers reported turning to jobs in the fast-food industry as a stopgap during periods of layoff.

Part-Time Work

Management has also sought to reduce labour costs by shifting to more part-time and casual employment. With the shift to more flexible labour, the union attempted through the 2004–08 collective agreement to regulate the number of workers who are considered part-time, stating that only 33 per cent of each department can be classified as part-time. Part-time casino employment is defined as employees who are regularly scheduled to work fewer than 30 hours per week. However, part-time employees can be scheduled for more than 30 hours per week without being considered full-time for a period not to exceed 45 calendar days.63

During “boom” times, Casino Windsor used part-time casino work conservatively. For instance, while the 2004–08 collective agreement mandated that part-time workers comprise a maximum of 33 per cent of the workforce, the part-time workforce made up only approximately 20 per cent in 2005.64 Part-time employees also symbolized the relative prosperity of the full-time workforce, where full-time workers would forgo peak tip shifts (weekends). Put simply, full-time workers’ tips were so lucrative during the 2004–08 period that many felt they could take peak tip shifts off work. Thus, part-time workers, willing to work weekends and other socially undesirable shifts, were seen by well-paid full-time employees as a means to secure social time off. When the casino was making more profit, part-time workers more or less functioned to allow full-time employees the flexibility to work standard hours.

Part-time workers were also used as a tool to improve relations between management and employees. A Windsor Star story noted in 2002 that, “in a move to improve relations between the casino and its employees, [casino spokesperson Jim] Mundy said an agreement between management and the union will give workers an opportunity to have ‘normal’ weekends off. ‘Under a separate agreement, we’re hiring people on a part-time basis to work weekends.’”65 A 2001 editorial in the paper also connected the lucrative incomes of full-time workers to the presence of part-time workers: “[Casino workers] make so much money, they don’t have to work full-time. So, they take days off without pay – an estimated 34,000 days last year. Some work four, three or even two shifts per week, yet still enjoy full benefits. Talk about made in the shade.” The editorial continued, “But this forces the company to hire hundreds of part-timers to fill shifts the fat full-timers decline to work. And the full-timers avoid weekends, the peak shifts of the casino industry.”66 Beginning in 2005, however, Casino Windsor increased its hiring of part-time workers, laying off full-time workers and rehiring them as part-time workers. As reported in the Windsor Star, “Difficult times are why Casino Windsor says it is ‘rebalancing the workforce,’ which means cutting jobs while turning some full-time positions into part-time ones.”67 Holly Ward, then Casino Windsor’s director of communications and community affairs, went on to say that “the majority of those affected will be going from full-time positions to part-time positions. That is to reflect the changing business volumes and of course having part-time employees gives you more flexibility.”68

While initially providing employee flexibility, part-time work now enables employer flexibility, signalling a shift in the utilization of part-time workers. Part-time workers provide the employer with the flexibility to adjust to high and low demand. Casino employees now view part-time workers as enabling the employer to run a “skeleton crew,” facilitating the bare minimum of casino staff necessary. Unlike previously, where part-time workers were scheduled for the less-desirable hours, full-time workers are now scheduled for the nonstandard hours (weekends) while part-time workers are scheduled for the more standard work hours (weekdays), allowing the employer to adjust to low patron volumes. Part-time status also allows the casino to avoid paying full-time benefits. While the company does provide an “optional” benefit plan whereby employees can opt in and pay 50 cents per hour worked in lieu, this coverage is limited to life insurance of $27,000 and prescription drug coverage and does not include the extended coverage given to full-time employees.

Casino workers reported that either they or their colleagues were being pushed to accept part-time work. Many mentioned the instability and the reduction in hours that accompany part-time work; indeed, one may not get called in at all. The change in hours and benefits creates financial insecurity. As Lucy, who has been pushed to part time, noted, “Part-time is not going to help raise a family.” In order to survive financially, some workers reported, they or their colleagues are seeking second jobs. Casino worker interviewees also discussed the taking on of second jobs through temporary employment agencies when pushed to part time. Some also reported that instability in work hours has driven workers into the union office asking for money, pleading for hours, and/or using the union food bank. Reflecting on the workforce’s increasing use of charity that coincides with reduced part-time hours, Catherine stated,

There have been employees who have been full-time and dropped down to part-time. And part-time [workers] that used to get four or five shifts now get two shifts. So, they are struggling to make ends meet. They’re working too many hours to collect unemployment and not enough to make ends meet. We’re seeing more of our employees reaching out to other services where they can go and get some help. They are actually going to the United Way.

In the 2008 round of collective bargaining, management proposed moving the department ratio cap of 33 per cent part time and 67 per cent full time to a 50/50 ratio while making positions in some departments completely part time.69 In the 2014 round of collective bargaining, the employer proposed eliminating the ratio cap altogether.70 These proposals did not materialize. Nonetheless, despite the 33 per cent cap, the casino workforce sees, as Chris phrased it, the “devious way” their employer makes certain classifications above this ratio. All casino workers reported that the employer consistently uses the maximum number of part-time workers in each department. Furthermore, many workers expressed suspicion that more and more full-time positions are being lost through layoffs and being replaced by part-time workers.

While departments have a 33 per cent part-time cap, a single department has many job classifications.71 As a result, some employees are concerned that their job classification may be made into 100 per cent part time. Workers who occupy what is treated as a lower job classification (that is, lower skilled) feel that their jobs are more vulnerable to becoming fully part time. For instance, cooks and kitchen stewards, slot technicians, and slot attendants are considered part of the same department. Because cooks and slot technicians are viewed as higher-skilled workers (and thus presumably more valuable to the employer), kitchen stewards and slot attendants fear that their classification may become solely part time while the cooks and slot technicians take up more full-time positions. Casino workers describe this move toward part-time work as the initial step in making the lower-valued jobs obsolete and eventually subsuming the duties of these lower-skilled positions into the higher-valued classifications.

While the part-time ratio established in 2004 remains in place, the classification of “casual” was introduced in the 2011–14 collective agreement. This third-tier worker is “utilized for the purpose of promotions, events, banquets, conventions, emergency situations, or similar activities.”72 In contrast to part-time workers, there is no cap on the number of casual workers allowed, presenting a concern for the casino workforce given the broad array of potential “utilization purposes.” As of 2015, Casino Windsor had 200-plus casual employees.73 Casuals are also not covered under several articles in the collective agreement, including vacation pay, overtime, pension plan, and health and welfare. For instance, unlike full- and part-time workers, casual workers are permitted only two undocumented absences per year. While still considered unionized employees, they are not actually covered by the majority of articles under the collective agreement and, by default, fall under the baseline regulations of the Employment Standards Act of Ontario.74

The casual workforce experiences more erratic scheduling and hours than the part-time workers.75 There is an expectation that the casual worker be present whenever needed.76 If not, the casual worker risks not being scheduled for any further shifts. The employer can also cancel or change a shift 72 hours prior to a shift commencing and there is no time length requirement in the case of an “emergency.” The introduction of the casual worker is seen by many casino workers as part of the employer’s desire to lessen its obligations to the unionized workforce. As Rick states, casual workers represent the casino’s “bigger agenda of knowing where they want to go and little by little they chip away at us [unionized workers].”

Outsourcing

The casino also cuts costs through outsourcing. Instead of managing the operations of a particular outlet within the casino that would utilize unionized workers on Casino Windsor’s payroll, the casino has leased out spaces to other private companies. Through outsourcing, the casino collects rent while incurring little cost. Outsourcing initially began in 2006 with a Starbucks outlet; since then, Casino Windsor has more aggressively used outsourcing.77 In 2015, the casino contained four non-union outlets: Starbucks, Taza (restaurant), Johnny Rockets (restaurant), and Landou (accessory and jewellery kiosk). An outsourced nightclub and spa opened in late 2015.

With the expansion of outsourced venues and its threat to unionized employees and membership growth, the union achieved language in its 2014 collective agreement that attempted to limit the proliferation of outsourced businesses. Before this contract, Sara stated, “We had absolutely nothing [i.e. prohibitive language]. So, they could have rented this out, that out.” While the collective agreement hinders outsourcing through the direct layoff of employees, it does not protect against unused space in the casino becoming a non-unionized, outsourced venue. Moreover, the language does not allude to how the space became unused or how long it was unused. This vagueness is also on the minds of casino workers. As Ryan stated, “There’s a loop hole and they [management] know it. They shut down a restaurant for a day, they’ll outsource it.” Workers also expressed uncertainty regarding how long this “protective” language will last, as there was concern that it could be taken away in the 2018 round of collective bargaining.

For workers, the use of outsourcing is viewed as a cost-cutting method that increasingly calls into question the longevity of unionized employment at Casino Windsor. The casino expands its offerings – like the nightclub – but the unionized workforce is not expanding with it. Indeed, management is excluding the unionized workforce from benefitting from expansion into non-gaming options, as these additional positions are being filled by non-union workers, further decreasing the facility’s ratio of unionized to non-unionized workers.78 Sara pointed to the more general push to get rid of unionized employment: “If they [management] have enough opportunity, they just want to keep the core [gaming] business and sell off everything else.”

Increasing Discipline

Casino Windsor workers also pointed to the increasing disciplinary action that they have experienced over the years. A local labour leader, Tom, commented on the use of constant surveillance to discipline and eliminate employees and how this is exceptional to the casino industry:

The casino abuses, what I believe, and what our union believes, is the spirit of what trust means, what integrity means, what honesty means. … Imagine now […] being watched 7-24. … And in an industry that’s got such great surveillance and sophisticated surveillance, and surveillance that they could look at tapes on an ongoing basis. We believe that in a lot of circumstances they look for trouble versus dealing with real trouble. We have multiple grievances as a result of this. And that doesn’t happen in any other environment. … The surveillance is tough and the definition of honesty and integrity is so narrow that you’d almost have to be God not to be caught off guard from time to time.

Workers view the employer’s high level of surveillance and increasing use of disciplinary action as a means to cut labour costs.79 Workers also perceive that the increasing disciplinary action is connected to falling revenues. Mapping onto when revenues started to decline in 2001, when the 2004 round of collective bargaining broke down the casino workforce went on a 41-day strike for “respect” from the employer – code for asking the employer to decrease surveillance, disciplinary action, and dismissal.80 During the strike, a casino worker, signalling the importance of respect as it relates to discipline, told the Windsor Star, “If they give us 30 or 40 cents a year raise, fine. But we want respect. We don’t want to be written up for every little thing. Or suspended. Or fired.”81 On the picket line, other casino workers complained about being disciplined for punching in early, being disciplined in front of customers, and being disciplined over their appearance.82 Reflecting on this strike, Sandra commented that “we were trying to make a point to our employer that there was no respect in the workplace from our employer to employees. And I remember standing in front of the casino and everyone was chanting, ‘Respect, respect.’ Yeah, it was major.”

Workers also discussed management’s increasing use of investigative suspension as a means of disciplinary action. Under the 2014–18 collective agreement, while management investigates a potential disciplinary infraction, “the Company has the right to suspend the employee, with/without pay, for up to five days.”83 Sara stated that “people are getting put on suspension constantly. That’s their motive, ‘Put them out! We’ll deal with it later.’ And they don’t pay us, we get no pay whatsoever. They are starving us. That’s exactly what they are doing. So, behave, behave when you come back – or you’re termed [terminated].” Workers see investigative suspension as another cost-saving measure, whereby the company recoups costs by cutting expenditures on wages.

The perceived lack of “respect” from their employer signals to workers that they lack value and are indistinguishable, disposable, and interchangeable. Samantha commented on how the employer treats the workforce as replaceable:

When I first started, everybody was excited and enjoyed it and now it’s, I hate to say, but such a miserable place to work. Like people say, “Well, I am thankful I have the job.” But yes, I am too, but I don’t like feeling like I have to be thankful that I have this job. You are making me feel like, “We can get rid of you and get somebody else.” You know, and that’s how lot of people in the casino feel. Like they [the employer] have actually had questionnaires where they have asked us, “If you could get a comparable job, pay, would you leave?” “In a heartbeat!” That’s what the general workforce says because it is such a tough place to work.

As Samantha explains, management not only considers the external labour market but gauges the workforce’s desire for mobility through workplace surveys. Indeed, workers see management using negative sanctions to gain discipline and effort from the workforce while, arguably, management is aware not only that workers would leave but also that they likely will not because comparable compensation is not available elsewhere. Finally, Lucy discussed feeling undervalued by management: “Being told that you [casino workers] are not good enough all the time, but if you look in publications, we have the best customer service. But the employer does not treat their staff that way. Everybody is horrible.” Lucy signals the disconnect between the management’s treatment of employees and the workers’ provision of quality customer service. Below, I explore why Casino Windsor workers not only remain despite the lack of “respect” but provide “the best customer service.”

A Captive Labour Market and “Award-Winning” Customer Service

Among Casino Windsor employees, there is low turnover, long tenure, and extremely tight seniority. 84 They remain at the casino despite declining rewards and conditions because of the relatively high compensation. Moreover, not only do workers remain, but they also provide award-winning customer service. In July 2014, Casino Windsor was awarded (for the fourth time) TripAdvisor’s Certificate of Excellence Award for Customer Service, meaning that the travel website’s users rated the property the best of the 35 hotels in the area.85 In 2016, in response to the casino’s sixteenth straight Reader’s Choice for Best Hotel award from Casino Player magazine, James Hollohazy, director of resort operations, praised Casino Windsor employees for their exceptional service: “It is an honour to be awarded this prestigious award. I am incredibly proud of the unparalleled service our employees provide every day to make our guests feel welcome and appreciated.”86

Casino Windsor workers not only remain at work but provide quality customer service. This service results from the workforce’s immobility, as the workers exist in a captive labour market. Three defining features of this context have rendered the casino’s employees immobile/captive: the Windsor area’s pattern of record high unemployment, casino workers’ inability to find comparable employment, and the casino’s placement on an international border.

Windsor’s Unemployment Rate

According to casino workers in Windsor, the city’s high unemployment rate constitutes a strong deterrent to quitting their jobs, despite their expressed dissatisfaction with declining rewards and working conditions.87 Diane asked, “Where it is the highest unemployment rate in Canada, where are you going to go?” High unemployment not only increases the likelihood that workers will remain at their current employer but also can compel workers to increase their work intensity at their current employer.88 Where unions are present, however, effort typically tends to be mediated through a bilateral bargain, where greater union power equals lower levels of worker effort.89 Despite union presence, Casino Windsor management’s use of video surveillance combined with the threat of dismissal functions to discipline and elicit effort from Casino Windsor workers.90 In the primary sector – that is, high-paying and high-skilled jobs – management tends to elicit worker effort mainly by positive motivation associated with “bureaucratic control.”91 In contrast, Casino Windsor utilizes the threat of dismissal – enforced through video surveillance – combined with the area’s high unemployment rate to ensure that workers not only remain but “work hard.”

Absence of Comparable Compensation

The casino workforce’s captivity is further founded in their position in a region where comparable compensation for similar work is not available. Casino Windsor, largely because of collective bargaining, provides compensation that is higher than what can be found in any low-skill service workplace in the region. The Casino Windsor workforce and management are both well aware of this. For instance, during a 2014 interview, a top executive at the casino acknowledged that its compensation package cannot be found anywhere else in Ontario. “We are seen as a good employer. Probably wages aren’t what you get in the manufacturing side, but our average wage is $18/$19 an hour which is very high for the service sector, and you’ve got great benefits,” the executive said. “If you are a server, you are not gonna make anywhere more in Ontario than you will here.” Put simply, both workers and management recognize that no comparable jobs with similar compensation are available in the region or even the province. Higher compensation raises the cost of job loss, providing workers with an incentive to supply effort.92

Casino worker interviewees often mentioned that they saw few employment alternatives outside of minimum-wage work. For workers with nowhere else to go, job loss from the casino results in a sharp decline in living standards. Lucy stated, “If I were to lose this job, there is no other job here [in Windsor] that’s more than minimum wage that I could get if […] I don’t know what we would do.” Indeed, because of these workers’ low skill set, minimum-wage work tends to be the only option available outside of the casino.

Workers tend to stay at the casino. Their low turnover, long tenure, and extremely tight seniority due to minimal new hires result from the relatively high compensation for their work. Matt explained that the casino offers lifelong employment yet added the caveat that the casino’s management would prefer higher turnover:

I mean yeah, it was a good thing where people go “Hey it is another Chrysler or another Ford’s or something that is there for a while.” At least in this area, we still have that mentality that when you are in a job, the majority of the people tend to stay there for 30 to 35 years. Upper management at the casino, they had this conversation with me about turnover. Because in Vegas you might not be at Caesars for 5 or 10 years, you could go from this company to this company to this company […] and so they said, “Well I think it should be that way here.”

Despite declining working conditions and increased disciplinary action from management, Casino Windsor workers continue to treat their employment as a lifelong job. Indeed, in terms of tenure and turnover, this workforce is “loyal.” This loyalty is coerced, however, in the sense that it results from the lack of comparably compensated employment in the region’s low-skill service sector.

An International Border

With its placement on the border with Detroit and the greater Michigan area, Casino Windsor served a large population with a demand for gambling.93 Soon after it opened, however, Detroit passed a referendum allowing the city to host casinos. Losing its monopoly in 1999–2000, Casino Windsor faced competition with three major gaming operators in Detroit. All four casinos were located within six miles of one another. This competition placed increased pressure on Casino Windsor’s management to cut costs.

A result of the international border is that Casino Windsor workers experience the pressures of increased competition for regional gambling dollars but none of the employment opportunities. Unlike Las Vegas, where workers can “jump from casino to casino” if unhappy with their employment, in Windsor, casino workers cannot simply work on the other side of the Canada-US border. Diane compared work at Casino Windsor to casino work in Las Vegas, stating that “in Nevada, I can work at mgm today and get frustrated and say, ‘Go kiss my ass! I’m done!’ and then go get hired at Caesars. Or I could get hired at Bally’s, right. So, I mean they will generally go from casino to casino.” Another casino worker, Sara, discussed the decline of job quality and the immobility of the workforce that result from Casino Windsor being the only Canadian casino in the region. “At least once every five years they [Las Vegas casino workers] are going to a different casino to work at. Trying to get either better wages or better tips,” she said. “Whereas here, we have no place to go to. You are only here. Yep. There isn’t another casino to jump into. So, you can’t try to advance.” While Casino Windsor workers herald Las Vegas as more worker friendly because of worker mobility, high union density – driven in part by the mobility of workers – on the Las Vegas Strip is also important. Since 1989, over 30,000 casino workers have joined the Culinary Union (here Local 226), more than doubling the union’s membership and bringing union density on the Las Vegas Strip to 90 per cent.94 A major facet of the union’s success (and the resulting high union density) is the unusual labour-market conditions in Las Vegas. The city’s labour market is characterized both by operators experiencing labour shortages and by casino workers having the ability to leverage their interests by moving across operators, creating competition between operators for workers. Labour shortages and mobility have facilitated the growth of union density in the area and the union’s leverage.

“We Keep This Place Open”: Reclaiming Worth through Customer Service

Under these conditions, casino workers have internalized the mantra that providing quality customer service in a competitive gaming market is crucial to ensuring that their livelihoods remain intact. Casino workers believe that customer service is what sets Casino Windsor apart from the competition and keeps its doors open. For instance, Karl spoke to the “unparalleled” customer service at Casino Windsor: “The casino makes it [Windsor] a destination. We win everything: best gaming in the Detroit region; best steakhouse in the Detroit region; best tables in the Detroit region.” He added, “If you’ve ever been to one over there [in Detroit], it’s not the same.” Many workers also suggest, however, that management’s push to cut labour costs is done without accounting for potential impacts on customer service. Despite these cuts and the potential of negatively affecting the ability of the workforce to provide quality service, casino workers stressed the importance of offering quality customer service. For instance, Rick discussed management’s use of skeletal staffing as a labour-saving strategy and management’s disconnect from understanding its impact on customer service. Put simply, casino workers see their effort as allowing Casino Windsor to remain competitive despite the actions of management. As Rick explained, “We’ve been able to survive so many of the hurdles we have had: 9/11, non-smoking, three casinos across the border. One thing after another, after another, and we keep bouncing back. And it is not because of anything management does. It is because of the job that we put forth.” In his words, “No matter how we are shit on by the company, we still go above and beyond in terms of customer service.” Diane also commented on the disconnect between management’s treatment of the workforce and the workforce’s provision of customer service, in relation to keeping the casino competitive and open:

And I think from a worker’s perspective … I can tell you, we don’t feel any appreciation from … the higher ups. I mean because clearly if you have a regular customer, they don’t come back because of the ceo or the cfo or the vice president, they come back because of the everyday workers and the treatment they get on the floor. … We are the ones keeping this place open! … I think there is a big disconnect between the people who make the decisions around here and the people who do the job.

Laying claim to the provision of quality customer service allows workers to reclaim a sense of value, despite the losses and disciplinary actions they have experienced over the years. Providing quality customer service affirms their value in the face of constant reminders (for example, layoffs, part-time and casual work, outsourcing, and disciplinary action) that they in fact have little value. Furthermore, workers’ reclamation of their value via quality customer service takes on an oppositional stance toward management. Indeed, as workers reclaim their own sense of respect – something that declining working conditions and disciplinary actions had threatened – they also highlight that management does not appreciate or recognize the value workers bring in terms of customer service. Workers view management’s not recognizing this value as an error because Casino Windsor would not be viable without them, the workers.

Conclusion

Casinos are emblematic of a strategy to create low-skilled service jobs in economically depressed cities. American states and Canadian provinces encourage host communities to develop casinos based on the ability of these facilities not only to create jobs but to provide “good jobs.” Existing research offers competing scenarios of what casinos mean for casino workers in host communities. Research has found that workers benefit from casinos through employment, wage growth, and high union density in the industry. Other research, however, has found that casinos exploit not only their host communities but also their workers. Nonetheless, the quality of casino jobs has attracted little scholarly attention, and what research there is focuses on “core” casino locations despite the increasing placement of casinos in more peripheral and economically devitalized areas.

Casino Windsor, in Canada’s economically struggling automotive capital, initially provided an economic opportunity – wages, tips, benefits, and union representation – and “good jobs” for workers with employment histories in the low-skill service sector. Beginning in the early 2000s, however, wages began to stagnate and tips declined. The casino’s management in turn sought a more casual and flexible labour force while increasing disciplinary action against employees. Consequently, Casino Windsor employees have experienced a decline in job quality.

Previous research highlights the mobility of casino workers, either through “chasing tips” (i.e. seeking employment at another casino) when unhappy with their employment and/or viewing their work in the casino industry as temporary.95 In contrast, Casino Windsor operates in a captive labour market: the city has a high unemployment rate, offers no alternative employment that provides comparable pay, and is situated near an international border. Thus, workers lack mobility and, as a result, are coerced into providing quality customer service. Casino workers remain and continue to provide award-winning customer service despite the declining rewards from and increasing disciplinary action by their employer. Casino Windsor workers do not view their “loyalty” (seen in low turnover) and provision of effort (award-winning customer service) as a choice. Instead, they identify their provision of quality customer service – in spite of what they see as management’s reckless cost-cutting/labour-saving strategies – as the main mechanism that keeps Casino Windsor open and their jobs intact.

In the crudest sense, Casino Windsor workers have likely made more money than they would have if the casino had never come at all. Yet, Casino Windsor workers share a story of loss and disempowerment, in the context of precarious work and disciplinary actions by which management diminishes workers’ value. How casino workers cope with these losses, however, is through laying claim to the provision of “good service.”96 Casino Windsor employees deal with precarity and immobility by reclaiming their value, measured in terms of good service, despite management’s efforts to make them feel replaceable and valueless. In doing so, these workers, in their minds, become “special” and unreplaceable, thus preserving some of their own sense of worth in the face of depersonalization at Casino Windsor.

When speaking about declining conditions and management’s disrespect, workers contrast the little value that management offers them with their own quality service provision and value. In doing so, workers not only reclaim a sense of agency and worth but also oppose management.97 Casino Windsor workers have also framed their strike actions as centring on securing “respect” from management rather than on monetary issues. This relates to Kendra Coulter’s findings in the retail industry, where a major driver of worker organizing centred on combatting management disrespect and reclaiming the workers’ sense of worth and value.98 Indeed, these labour struggles are as interpersonal as they are monetary. Stemming from the transformation of work quality over time – seen in management betraying the casino workers’ expectations and prior experiences of job quality – Casino Windsor workers do adopt an oppositional stance: that they matter, despite management’s assertions otherwise.99

It is true that Casino Windsor provided an economic opportunity for women employed in the service sector in Windsor. However, this employment opportunity is similar to that of the male-dominated automotive industry, in which workers became captive to the automotive sector and its increasing precarity. Indeed, the attempted transition of Windsor’s economy toward a more service-oriented economy via a casino entailed the creation and exploitation of a similarly captive labour market in which workers do not easily escape.

Casinos in Ontario, as in many jurisdictions, were conceived as export-led forms of development that would capture gambling and tourist dollars from US patrons. Therefore, the province’s casinos were placed on Canada-US border sites, such as Windsor and Niagara Falls, which were also experiencing the impacts of deindustrialization. However, US states quickly responded with their own casinos, leading to fierce competition for cross-border gamblers between provinces and states and their respective operators. This competition concerns the (largely) free-moving Canadian/US gambler, yet casino workers have little opportunity for movement; their employer’s location contributes to the workers’ captivity. More recently, the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation, with its 2010 “Modernization Plan,” has attempted to move from a strategy that prioritized deindustrializing border cities to one that favours densely populated regions, like Toronto, to both increase access to larger pools of existing gamblers and create new gamblers.100 Indeed, with the original border sites, the focus was on export-led development – bringing in “new” out-of-country dollars from US patrons – whereas now the strategy seems to be a form of import substitution whereby the Ontario government relies on gambling dollars from its own residents by offering more gambling options to more of its constituents. Will this shift in strategy result in a worsening of the captive status of casino workers at border sites? Arguably, yes. Reinvestment in these properties may diminish as a priority and Canadian border sites may continue to lose market share to their US competitors. Will the creation of casinos in densely populated city centres also create a captive labour market of casino workers? If there is a single operator in a region and the casino offers higher remuneration than other service-sector employers then, to a degree, yes. As the province will likely offer only one licence to a single operator in a region, monopsony power will likely be given to the employer. Yet, labour force captivity in these city centres will likely be less extreme than in deindustrializing border cities experiencing crippling unemployment rates.

These findings raise questions concerning the labour markets into which casino developments – which are state sponsored and are legitimized to host communities as “good job” creators – are placed. Governments are increasingly turning to casinos as an economic development tool in areas that are economically depressed, in addition to placing these developments on borders in an effort to (re)capture gambling dollars from other jurisdictions. With states/provinces promising host communities “good jobs” to justify casino developments, researchers and public policymakers should consider whether such developments will create and potentially exploit a captive labour supply, leading to the creation of not-so-good jobs.

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. This manuscript would not have been possible without the support of Dr. Elaine Weiner and the participants who generously gave their time to participate in this study.

1. Thomas A. Garrett, “Casino Gaming and Local Employment Trends,” Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis 86, 1 (2004): 9–22; Chad D. Cotti, “The Effect of Casinos on Local Labour Markets: A County Level Analysis,” Journal of Gambling, Business, and Economics 2, 2 (2008): 17–41.

2. Dean Gerstein, Rachel A. Volberg, Marianne Toce, Henrick Harwood, Robert Johnson, Tracy Buie, Eugene Christiansen, Lucian Chuchro, William Cummings, Laszlo Engelman & Mary Ann Hill, Gambling Impact and Behavior Study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission (Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, 1999); Christopher Mele, “Casinos, Prisons, Incinerators, and Other Fragments of Neoliberal Urban Development,” Social Science History 35, 3 (2011): 423–452.

3. Ellen Mutari & Deborah M. Figart, Just One More Hand: Life in the Casino Economy (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

4. Jeffrey J. Sallaz, “The House Rules: Autonomy and Interests among Service Workers in the Contemporary Casino Industry,” Work and Occupations 29, 4 (2002): 394–427; Sallaz, The Labour of Luck: Casino Capitalism in the United States and South Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); Chloe E. Taft, From Steel to Slots: Casino Capitalism in the Postindustrial City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

5. A Unifor informant indicated that the turnover rate for Casino Windsor was 8 per cent in 2017.

6. Captive labour forces are defined by their context, tending to exist in single-industry and single-employer towns where competition among employers is low or absent and where workers’ access to other sources of employment is limited. See Gerda R. Wekerle & Brent Rutherford, “The Mobility of Capital and the Immobility of Female Labour: Responses to Economic Restructuring,” in Jennifer Wolch, ed., The Power of Geography: How Territory Shapes Social Life (Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1989), 130–172.

7. Melissa K. Gibson & Michael J. Papa, “The Mud, the Blood, and the Beer Guys: Organizational Osmosis in Blue-Collar Work Groups,” Journal of Applied Communication Research 28, 1 (2000): 68–88; Kristen Lucas, “Blue-Collar Discourses of Workplace Dignity: Using Outgroup Comparisons to Construct Positive Identities,” Management Communication Quarterly 25, 2 (2011): 353–374; Kristen Lucas & Patrice M. Buzzanell, “Blue-Collar Work, Career, and Success: Occupational Narratives of Sisu,” Journal of Applied Communication Research 32, 4 (2004): 273–292.

8. Lucy Dadayan, “State Revenues from Gambling Shrinking,” in Council of State Governments, The Book of the States (2016), 393–404.