Labour / Le Travail

Issue 86 (2020)

Presentation / Présentation

Back-to-Work Legislation Roundtable

Class Struggle from Above: The Canadian State, Industrial Legality, and (the Never-Ending Usage of) Back-to-Work Legislation

In capitalist societies, few moments bring to the surface already existing class divisions more than a strike. When the poor, the dispossessed, the disadvantaged, and all those who work for wages engage in mass protest – through the withdrawal of their labour or by the mass disruption of bourgeois normality – the everyday struggles of people navigating already existing oppressions erupt into broader public consciousness.7 The historical significance of these struggles will vary depending on time and space, but these conflicts continue because, as Bryan Palmer and Gaétan Héroux argue in their exceptional history of Toronto’s poor, class inequality is produced structurally as a relationship to capitalism and its unequal division of the surplus derived from human labour power. Yet, because class is built on a foundation of power predicated upon unequal exchange, it is shaped and moulded by “the crucible of struggle and resistance.”8 In that crucible, Marx and Engels observe, the bourgeoisie may produce “its own grave-diggers” because it creates and is dependent upon the misery that compels working people to resist.9 Strikes can take many forms, including prisoners refusing the orders of the guards, women refusing to perform culturally imposed domestic labour, Indigenous peoples placing their bodies between their lands and colonial development projects, and working people walking off the job to pressure a recalcitrant employer. While strikes can occur in isolation over issues pertaining to wages or workplace conditions, they can also break out into broader challenges to existing social relations. In these moments of crisis, strikes expose and break down the contradictions on which capitalist societies are founded.

While strikes occur in all capitalist countries, the Canadian state has always been defined, in the words of Leo Panitch, by its particular “commitment to private capital as the motor force of the society.”10 These early commitments, rooted in English Canada’s peculiar embrace of colonial Toryism, witnessed an economic élite utilizing the state to foster capital accumulation first through Indigenous disposition and later through active recruitment of a landless working class to labour in large public work projects and fledgling factories in the 19th and early 20th centuries.11 Since the end of World War II, the foundations of the Tory state may have shifted to a more coercive liberal order, yet the same philosophies that guided the 19th-century state regarding labour relations have led to a system that remains wary of working-class struggles that challenge the basic foundations of accumulation, even on the margins.12

Particularly exceptional about the state’s continuous intervention in labour disputes are the numerous legal barriers erected by the state before workers can engage in strike activity. And notwithstanding those numerous legal barriers, governments continue to intervene to end strikes through what Leo Panitch and Donald Swartz describe as “ad-hoc back-to-work legislation.”13 For Panitch and Swartz, each occurrence of back-to-work legislation passed by federal and provincial governments since 1950 – which stands at more than 144 separate occurrences as of 202014 – represents a turn toward “permanent exceptionalism.” What is contradictory about the increasing use of back-to-work legislation by Canadian governments is that the coercive acts are “continually portrayed as exceptional, temporary, or emergency-related, regardless of how frequently they occurred or the number of workers who fell within their scope or were threatened by their example.”15 Since the 1950s, and with increasing frequency by the end of the 1970s, the so-called “temporary” and “exceptional” nature of back-to-work legislation has been muddled by government insistence that it respects the foundations of industrial legality but must restrict the ability of workers to strike in order to solve a looming emergency – real or imagined – within the specific regime of capitalist accumulation.

When the capitalist offensive turned against the postwar Keynesian consensus in the 1970s, back-to-work legislation became the state’s rather blunt instrument with which to discipline Canadian workers and weaken resistance to the otherwise violent process of neoliberalization.16 Often these restrictions weakened workers’ abilities to challenge broad macroeconomic changes designed to squeeze workers’ capacities to fight for higher wages, as occurred during the anti-inflation fights in the 1970s and early 1980s. These instruments were equally effective in weakening the ability of teachers and nurses to challenge imposed austerity within the public sector throughout the 1990s and 2000s. So effective have the state’s coercive measures become that Panitch and Swartz’s thesis was demonstrated clearly, and certainly unwittingly, by former Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper when, in defending his decision to legislate Air Canada workers back to work in 2012, he asserted that he would

be darned if we will now sit by and let the airline shut itself down. Under these circumstances at the present time, this is not what the economy needs and it is certainly not what the travelling public needs at this time of year. As much as there’s a side of me that doesn’t like to do this, I think these actions are essential to keep the airline flying and to make sure the two parties find some way through mediation arbitration of resolving these disputes without having impacts on the Canadian public.17

Harper’s position repeated the now consistent pattern of neoliberal governments that recognize the legitimacy of industrial legality yet act in a direct way to undermine any pretext to supporting that model when it challenges the political or economic agenda of governments and capitalists.

While Harper’s government did not shy away from championing its anti-union animus, the present-day concoction of reactionary Conservative attitudes toward workers represents a crude form of a now decades-old pattern of the state undermining core labour freedoms when worker actions threaten or challenge the dominant patterns of accumulation. Notwithstanding this history, stubborn questions remain. Why do Canadian governments continue to use back-to-work measures, even though workers are utilizing the strike weapon (whether legally or illegally) far less than in the past? Has the use of these measures contributed to a weakened movement now more reluctant to utilize the strike weapon? The answer to such questions lies firmly in the Canadian state’s long history of regulating workers’ collective action through the law, which has always been predicated on undermining and subjecting working-class militancy. What is unique about the Canadian state’s regulation of labour relations is that the ability of workers both to bargain and to strike are specifically and narrowly defined by the capitalist state. In examining this history, this short article will look at the first use of back-to-work legislation in 1950, in order to demonstrate that the basic elements of the state’s intervention into labour disputes – deference to public emergencies and temporary restrictions on legal rights to strike – were built into the foundation of Canada’s current industrial relations system. The article will then conclude by examining how back-to-work legislation has become the sharp edge of the ongoing state assault on post–World War II union freedoms, disciplining labour to a point that strikes rarely threaten the political or economic agendas of the country’s ruling classes. In other words, the now frequent use of back-to-work legislation ends up highlighting the weakness of the existing labour movement and, perhaps more importantly, the inadequacies of a legal regime that is built to weaken workers’ ability to strike.

On Restrictions of Strikes in Canadian Labour History

Historically, Canadian workers have never been entirely free to collectively challenge the power of employers. Throughout the 19th century, the law constructed numerous criminal boundaries around workers’ strike action.18 Although many of these criminal restrictions were formally removed after 1872, police and employers routinely used violence on picket lines to break workers’ strikes, especially when those actions proved threatening to the political and economic order.19 While this was certainly demonstrated during the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, that struggle was only the most sensational in a long history of state repression and violence that characterized strike activity in Canada prior to 1944. To be sure, not all strikes in the pre-1944 period challenged the pillars of the capitalist economy or threatened to undermine the power of the state. While some erupted into violence, many others did not. Yet, whenever workers demanded recognition in industries where capitalists steadfastly refused to deal with the union, state or employer violence always loomed heavily in the background of any dispute.20

After unprecedented strike activity during World War II pushed the state to recognize basic worker freedoms in law, state restrictions on collective activity took new but equally restrictive forms.21 In the postwar period, while strikes occurred with some consistency, how and why they occurred became more predictable and more narrowly focused on concluding unions’ collective agreements. Additional legal boundaries included mandated strike votes, and even then, strike action was further delayed until both sides had declared a legal impasse during collective bargaining. Workers were then required to participate in compulsory conciliation and in most jurisdictions, governments implemented mandatory cooling-off periods before picket lines could be established.22 Although unions received corresponding legal benefits in accepting these limitations, the regime of industrial legality required that union leaders “channel union activities away from spontaneous rank-and-file action” for fear of state reprisal in the form of injunctions, fines, or even imprisonment.23

Following the rules, however, did not guarantee that workers and their unions were free from abusive employer and coercive state intervention during labour disputes. Throughout most of Canada’s history, courts have been present to police the boundaries between the powers that flow from property ownership and workers’ ability to challenge that dominance through the collective withdrawal of labour.24 Perhaps the most glaring example of class biases in the laws surrounding strikes can be found in the form of judicial intervention in labour disputes through employer-obtained injunctions. These injunctions – grounded in the common law’s defence of property and contract – were defended on the grounds that collective picketing action tortuously interfered with employers’ ability to run their business.25 Once picketers’ activities were diluted by the law, violence routinely escalated as picketers watched employers utilize the reserve army of the unemployed – scab labour in worker vernacular – shuffle into their former jobs.26 The state’s promotion of picket line violence through easily obtained injunctions played a significant role in the labour radicalism of the 1960s, where workers’ challenges to employer, union, and even gendered and racialized power imbalances were often confronted by spontaneous strike action by a new generation of workers.27 Although numerous government studies at both federal and provincial levels throughout the 1960s and 1970s recognized that injunctions were heightening tensions on picket lines, very few governments placed restrictions on the ability of employers to obtain court orders restricting workers’ collective actions.28

Enter Back-to-Work Legislation

Notwithstanding the numerous legal obstacles that unions must face before they can engage in legal strike activity, and the ease by which employers can obtain injunctions, governments continue to intervene in labour disputes. In fact, Canada remains one of the few countries in the world that routinely utilize the legislative weapon to formally intervene in legal strike activity and thus weaken the collective freedoms of workers to strike.29 What accounts for this frequency? In many ways, the state’s openness to using the instrument of back-to-work legislation is correlated with the construction of the regime of industrial legality itself. When governments turned away from open coercion on the picket lines after the construction of Canada’s amalgam of American Wagnerism with a strike-delaying conciliation regime in 1944, it reshaped the boundaries of class struggle through the institutional lens of what we today define as labour law. That institution, as Judy Fudge and Eric Tucker remind us, was built on a foundation of quid pro quo, where workers and their unions conceded to their unrestricted ability to withdraw their labour “in the form of immunities for workers or unions, or in the form of duties imposed on employers that facilitate the freedom to associate and bargain collectively.”30

Yet, for the system to have legitimacy among certain cross-sections of the working class, governments had to appear – on the surface, at least – as neutral arbitrators in the class struggle. While the coercive powers of the capitalist state remained, industrial legality required workers and unions to maintain a degree of consent for the rules of the system to work effectively. For Panitch and Swartz, the new system of legality reshaped the class struggle such that “what before had taken the appearance of the charge of the Mounties now increasingly took the form of the rule of law by which unions policed themselves in most instances.”31 While union leaders had long patrolled worker militancy in order to win a contract, under the rules of postwar legality these policing tactics took different forms. In the postwar period, a worker became a union leader by developing an expertise in the new legal system of grievances, arbitration, and winning material gains during regular rounds of collective bargaining. Under this system, the skills of organizing and building working-class consciousness through worker empowerment became of secondary importance. Moreover, while the strike remained an important tool within this new model of industrial relations, strikes themselves were highly regulated and leaders were keen to make sure that the boundaries of class struggle adhered to the rules defined by the law.

Ironically, when the Liberal government led by corporate lawyer–turned-politician Louis St. Laurent became the first to use back-to-work legislation, on 30 August 1950, it was based on a quid pro quo with the unions involved. In this dispute, members of seventeen separate railway and telegraph unions representing 125,000 workers walked off the job after the unions had failed to successfully bargain for improved wages and expanding union membership in non-union railway shops, including hotel and water employees.32 Perhaps more important to the membership, however, was the insistence that the unions not concede on the 40-hour workweek, which the company had been stubbornly refusing to recognize at the bargaining table. In fact, the union had substantial support from the membership – demonstrated by large mass meetings of 10,000 Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway (cpr) workers on the day the strike was announced – to push for a shorter workweek given that excessive fatigue was consistently a health and safety issue on the railways.33 Although the company had conceded modest wage increases, it was only willing to shorten the normal workweek to 44 hours (from 48) and offered vague commitments to bring in the 40-hour week at some point in the future if the union agreed to lower its wage demands.

Representing the largest strike in Canadian history to that point, the railway dispute placed pressure on all sectors of the economy, especially as the state mobilized for participation in the Korean War. In fact, the day the strike was called, newspapers were filled with fear-mongering stories predicting that communities in northern regions would be “starving” within days, warnings of massive layoffs across the country, and the typical bemoaning of unions abusing the strike weapon to punish the general “public.”34 A. R. Mosher, president of the Brotherhood of Railway Employees, and Frank Hall, chairman of the negotiating committee, responded to these claims by apologizing to the Canadian public, placing the blame solely on the rail companies and their disregard for the health and safety of the workers on the line. Mosher went so far as to hint at the internal anticommunist fights within his Canadian Congress of Labour (ccl), suggesting that the rail companies’ inaction and disregard for the health and safety of the workers was providing added “comfort” to “subversive elements by this strike.” He went on to emphasize that “these elements will be glad to see a slowing down of a war effort directed against the Communists of North Korea.”35 Criticizing cnr president Donald Gordon and the alleged communists in his own union, Mosher aligned his public relations strategy with what Irving Abella describes as the “frenzy of anti-communism which swept the continent in the wake of the onset of the Korean war” to point out the greed of the railway capitalists while also playing on nationalist sentiments to win public support at the beginning of the Cold War’s first armed conflict.36

The unions were also quick to point out the Liberal government’s apparent indifference to the working conditions of railway workers. Having been deeply involved in the negotiations through the conciliation process and after the appointment of a special mediator, and having attempted to avoid backlash from the numerous companies dependent on the rail system, the governing Liberals wasted little time in attempting to end the strike. The government’s urgency was reflected in the fact that the day the strike began, the Liberals mobilized the Royal Canadian Air Force to fly mps back to Ottawa to hold a special “strike session” of Parliament in order to end the strike through binding arbitration.37 Although Prime Minister St. Laurent endeavoured to broker a deal through negotiations during the first days of the strike, the cabinet also leaked information stating that the eventual legislation would come with a threat that workers would follow the back-to-work order or risk losing their pension and seniority rights.38 As Parliament debated the issue, the threat of state-imposed arbitration brought calls of solidarity from unions across the country, with the United Electrical Workers and large locals within the United Auto Workers calling for a mass strike in support of the railway workers.39 In the words of the Globe and Mail labour reporter Wilfrid List, the government’s actions further “tightened the growing alliance” between the ccl and the Trades and Labour Congress in both their anticommunist and pro-nationalist ideologies, as well as their now firm belief in the sanctity of the new legal regime of industrial legality.

When Parliament debated the issue, St. Laurent outlined his government’s reasoning for intervention that reinforced how and why the state had to end even legal strikes. Despite claiming allegiance to “the principle of collective bargaining” and to the legal “institutions which have proved their value to the national economy of Canada,” the government had no choice but to “deal with what amounts to a national emergency.”40 St. Laurent insisted that his government was not intending to intervene in the process of collective bargaining between “equal powers” and recognized that the “strike had not been in violation of any law” but stated that in situations of national emergency even the most sacred of “normally private rights may at times amount to what becomes public wrongs.” In such an instance, the prime minister elaborated, the ability of workers to bargain and strike freely may inflict an “injury” that “is sometimes so great that it has to be given serious consideration because the existence and security of the state is the first and prior consideration for each and every one of us.”41 Although ccf members opposed the legislation, the eventual back-to-work bill was supported by the union leadership because the government conceded to wage increases and to the 40-hour workweek (later in 1951) that could not be eroded by arbitration. In other words, the back-to-work bill imposed binding arbitration – something the unions universally opposed – but the government restricted the arbitrator’s ability to impose a contract lower than the wage, workweek, and bargaining extension demands acceptable to the union leadership.

While smiling pictures of Mosher and Hall appeared the next morning in the Toronto Star alongside a booming headline declaring “Unions Commend St. Laurent,” the unions faced criticism for accepting the back-to-work order. The United Electrical Workers, recently ousted from the ccl for its alleged communist sympathies by Mosher himself, denounced the government’s actions and was critical of the union leadership for not challenging the back-to-work order.42 Meanwhile, Tommy Douglas, social democratic ccf premier of Saskatchewan, argued that “the introduction of the principle of compulsory arbitration shows how far we have drifted from democratic procedures in Canada. Collective bargaining is now to be replaced by binding 150,000 workers to the decision of one individual from whose ruling there is no appeal. This may make the Employers’ Association and the Manufactures’ Association happy but it will cause great concern to those who believe in the democratic right of workers to bargain collectively.”43 Responding to this criticism, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees celebrated the fact that “the principle of the forty-hour, five-day work week” was now acknowledged by government statute, notwithstanding the fact that it was buried in the back-to-work order. Mosher predicted that the government’s recognition of the 40-hour workweek in the back-to-work bill would “be used by thousands of other workers throughout Canada to gain similar improvements in their conditions of employment.”44 Mosher further elaborated in his annual presidential address to the union that the “strike was one hundred per cent effective.” To be sure, he acknowledged that the “calling off of the strike in compliance with the law” was “subject to derogatory remarks by some.” Yet he remained convinced that the gains made through the back-to-work order were an important material benefit for his members and that not accepting the back-to-work order “would probably have resulted in far more drastic and repressive legislation.”45 In arriving at this conclusion, the union leadership believed that the material gains provided by the back-to-work order necessitated following the law and conceding their right to freely bargain and to strike.

The State and the Never-Ending Use of Back-to-Work Legislation

St. Laurent’s foray into legislating the railway workers back to work set the pattern for how governments would apply this legal tool in the future: workers deemed essential or important enough to threaten national or provincial interests, or those who maintained the potential to disrupt important sectors of the economy, would be legislated back to work, usually with the promise of some form of third-party arbitration. Once public-sector workers had won similar legal freedoms in 1966 and 1967 at the federal level (and somewhat later in the provinces), the public nature of strikes placed government in the dual role of employer and legislator.46 That dual role and the government’s broad interpretation of what constitute a crisis – so aptly demonstrated in the 1950 rail dispute – suggested that public-sector conflicts allowed governments to bypass workers’ strikes through legislative intervention. And while legislative intervention allows for the use of third-party arbitration, that process takes the issue out of the hands of workers and transfers it to high-priced lawyers and professional arbitrators.47 Yet, there is some evidence to indicate that even the use of third-party arbitrators to settle disputes allows governments to avoid a political crisis but does little to actually address the workplace grievances that led to the strike.48 The point for the government, however, is that workers continue to work, and while the state can claim its allegiance to its regime of industrial legality, those rights are always subject to limitations when it is economically or politically necessary for capital and the state.

As Tucker demonstrates in his essay in this section, that formula was used in the period of neoliberalization, roughly from 1975 to 2002, in order to end 115 separate strikes. To be sure, public-sector struggles remain ground zero of government intervention in both legal and illegal strike activity. In private-sector disputes, there is often no such urgency as governments are more than willing to let private workers linger on picket lines if private employers can withstand prolonged strike action using legal injunctions and scab labour. In 2020, the conservative Saskatchewan Party refused to intervene in an ongoing private-sector dispute in the Co-op Refinery Complex, notwithstanding the fact that the government-appointed mediator recommended a settlement that was accepted by the union.49 In this dispute, Unifor workers have repeatedly been unable to stop the flow of scab labour into the plant because a court-imposed injunction prevents the union from “impeding, obstructing, or interfering with the ingress or egress to or from the applicant’s property” and allows the union to delay those attempting to cross the line only “as long as necessary to provide information, to a maximum of 10 minutes, or until the recipient of the information indicates a desire to proceed, whichever comes first.”50 Put more concretely, those wishing to cross the line merely had to indicate their desire to receive no information and drive through. Such wording made Unifor’s picket line weaker and allowed the company to drag the union back to court when any union action was deemed to impede access to the company’s property. Yet, even private-sector strikers are not immune from reactionary government intervention when those strikes appear to threaten the perceived stability of a local economy. In 1983, Grant Devine’s Conservative government in Saskatchewan ended a dairy strike, while Prime Minister Harper quickly legislated Air Canada and cpr workers back to work in 2011 and 2012 because of threats to the “economy.” These actions demonstrate that governments are more than willing to push aside the regime of industrial legality when it suits their interests.51

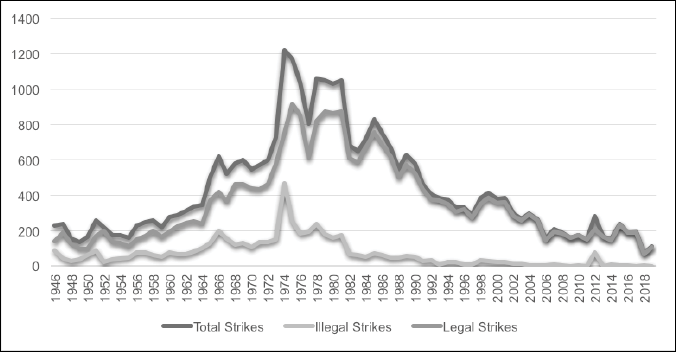

Figure 1. Total Strikes in Canada, Legal and Illegal, 1946–2019. Sources: Statistics Canada, “Work stoppages in Canada, by jurisdiction and industry based on the North American Industry Classification System (naics), Employment and Social Development Canada,”

Table 14100352, accessed 20 July 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410035201; illegal strikes calculated from Employment and Social Development Canada, Work Stoppage Directory, 1946–2019.

Note: I report on this data in more detail in Charles W. Smith, “Political Economy and the Canadian Working Class: Conflict, Crisis and Change,” in Heather Whiteside, ed., Canadian Political Economy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, forthcoming).

To be sure, governments are utilizing back-to-work legislation less frequently now than in the turbulent period of neoliberalization in the 1970s and 1980s. Yet, governments have ended legal strikes in over 29 instances since 2002. The decline in government intervention is perhaps not surprising given that workers are striking both legally and illegally far less frequently than in the past, as Figure 1 shows.

Explaining the absolute decline in strike activity in Canada requires a much richer examination of worker experience over the past four decades, but part of the explanation is clearly tied to how the Canadian state, through the law, regulates, manipulates, and weakens workers’ ability to strike. While recent constitutional jurisprudence has breathed some life into labour’s existing support for the regime of industrial legality, as Tucker and Alison Braley-Rattai show in this section, this is a poor substitute for the ability of workers to challenge the law rather than relying on contradictory support from the capitalist state.52 If the history examined here demonstrates anything, it is that workers’ reliance on the state will always come with corresponding trade-offs that weaken their capacity to challenge capital and the state. Until workers can see beyond the limitations of the existing regime of legality, governments will continue to utilize back-to-work legislation through real and imagined threats to the status quo.

7. Bryan Palmer, “‘The New New Poor Law: A Chapter in the Current Class War Waged from Above,” Labour/Le Travail 84 (Fall 2019): 53–105.

8. Bryan D. Palmer & Gaétan Héroux, Toronto’s Poor: A Rebellious History (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2016), 6. See also Bryan Palmer, “Approaching Working-Class History as Struggle: A Canadian Contemplation; a Marxist Mediation,” Dialectical Anthropology 42 (2018): 445.

9. Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, The Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 60.

10. Leo Panitch, “The Role and Nature of the Canadian State,” in Leo Panitch, ed., The Canadian State: Political Economy and Political Power (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977), 17.

11. Ruth Bleasdale, Rough Work: Labourers on the Public Works of British North America and Canada, 1841–1882 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018). Bleasdale masterfully demonstrates the complex system in which the state directed the construction of the massive public works projects that built the foundation for Canada’s future economy. It was, in her estimate, tied to a massive public undertaking that was dependent upon a transient labour force that had to be imported (largely from the ranks of the British and Irish working classes), who upon arrival in Canada were both exploited and criminalized as they attempted to earn a living and create community in the colony.

12. Ian McKay, “The Liberal Order Framework: A Prospectus for a Reconnaissance of Canadian History,” Canadian Historical Review 81, 4 (2000): 616–678.

13. Leo Panitch & Donald Swartz, From Consent to Coercion: The Assault on Trade Union Freedoms (Toronto: Garamond, 2003), 26–29.

14. Calculated from Panitch & Swartz, From Consent to Coercion, Appendix 2; Canadian Foundation for Labour Rights, Restrictive Labour Laws directory, n.d., accessed 17 July 2020, https://labourrights.ca/restrictive-labour-laws.

15. Panitch & Swartz, From Consent to Coercion, 30–31.

16. “Neoliberalization” is defined by Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell as a process that is shaped by the relative balance of class forces at any given moment within different capitalist formations. See Peck & Tickell, “Neoliberalizing Space,” Antipode 34, 3 (2002): 383. While the process of disciplining labour was universal across the capitalist world, it took on the form of intensified back-to-work legislation in Canada because it was meant to destroy the “social solidarity that put restraints on capital accumulation.” David Harvey, A Short History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 75.

17. Harper quoted in Bradley Bouzane, “pm Defends Action on Air Canada,” Montreal Gazette, 10 March 2012.

18. Eric Tucker, “‘That Indefinite Area of Toleration’: Criminal Conspiracy and Trade Unions in Ontario, 1833–1877,” Labour/Le Travail 27 (Spring 1991): 14–51.

19. For an overview of these strikes, see Bryan Palmer, “Labour Protest and Organization in Nineteenth-Century Canada, 1820–1890,” Labour/Le Travail 20 (Fall 1987): 61–83; Douglas Cruikshank & Gregory S. Kealey, “Strikes in Canada, 1891–1950: Methods and Sources and the Data,” Labour/Le Travail 20 (Fall 1987): 85–145. On some of the tensions and contradictions in these regulations, see Charles W. Smith, “Freedom of Association and the Political Economy of Rights: The Collective Freedoms of Workers after sfl v. Saskatchewan,” Studies in Political Economy 98, 2 (2017): 124–150.

20. The history of employer and state violence on picket lines is vast. For an overview, there is no better source than Bryan D. Palmer, Working Class Experience: Rethinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800–1991 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992). Other broad overviews include Desmond Morton, Working People, 5th ed. (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007); Craig Heron, A Short History of the Canadian Labour Movement, 3rd ed. (Toronto: Lorimer, 2012). Judy Fudge and Eric Tucker also examine numerous and violent strikes in their Labour Before the Law: The Regulation of Workers’ Collective Action in Canada, 1900–1948 (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2001). For some specific case studies, see Irving Abella, ed., On Strike: Six Key Labour Struggles in Canada (Toronto: James Lewis & Samuel, 1974).

21. Peter S. McInnis, Harnessing Labour Confrontation: Shaping the Postwar Settlement in Canada, 1943–1950 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), 145–181. See also F. David Millar’s exceptional history of the administrative structures constructed by the federal and provincial states to regulate the new collective bargaining legislation: “Shapes of Power: The Ontario Labour Relations Board, 1944–1950,” PhD diss., York University, 1980. For a more whiggish and sympathetic history of the state, the Liberal Party, and the construction of Canada’s model of industrial legality during World War II, see Taylor Hollander, Power, Politics, and Principles: Mackenzie King and Labour, 1935–1948 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018).

22. Judy Fudge & Harry Glasbeek, “The Legacy of pc 1003,” Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal 3 (1994/1995): 357–399; Judy Fudge & Eric Tucker, “Pluralism or Fragmentation? The Twentieth-Century Employment Law Regime in Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 46 (Fall 2000): 251–306; Fudge & Tucker, Labour Before the Law, 297–315; Fudge & Tucker, “The Freedom to Strike in Canada: A Brief Legal History,” Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal 15, 2 (2009/2010): 348–352; Daniel Drache & Harry Glasbeek, The Changing Workplace: Reshaping Canada’s Industrial Relations System (Toronto: Lorimer, 1992), 8–31; Larry Savage & Charles W. Smith, Unions in Court: Organized Labour and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2017), 30–40.

23. Andrew Jackson & Mark P. Thomas, Work and Labour in Canada: Critical Issues (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2017), 200. For a concrete case study examining the taming of worker collective action in the period, see Donald M. Wells, “Origins of Canada’s Wagner Model of Industrial Relations: The United Auto Workers in Canada and the Suppression of ‘Rank and File’ Unionism, 1936–1953,” Canadian Journal of Sociology 20, 2 (1995): 193–224.

24. Eric Tucker & Judy Fudge, “Forging Responsible Unions: Metal Workers and the Rise of the Labour Injunction in Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 37 (Spring 1996): 81–120.

25. On injunctions and torts, see Charles W. Smith, “‘We Didn’t Want to Totally Break the Law’: Industrial Legality, the Pepsi Strike, and Workers’ Collective Rights in Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 74 (Fall 2014): 89–121. See also Eric Tucker, “Hersees of Woodstock Ltd. v. Goldstein: How a Small Town Case Made It Big,” in Judy Fudge & Eric Tucker, eds., Work on Trial: Canadian Labour Law Struggles (Toronto: Irwin, 2010), 217–248.

26. Canadian Labour Congress, “Campaign against Strike Injunctions,” Canadian Labour 11, 11 (1966): 32.

27. Bryan D. Palmer, Canada’s 1960s: The Ironies of Identity in a Rebellious Era (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 212–241; Peter S. McInnis, “‘Hothead Troubles:’ Sixties-Era Wildcat Strikes in Canada,” in Lara Campbell, Dominique Clément & Gregory Kealey, eds., Debating Dissent: Canada and the Sixties (Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2012), 155–172; Joan Sangster, “‘We No Longer Respect the Law’: The Tilco Strike, Labour Injunctions, and the State,” Labour/Le Travail 54 (Spring 2004): 47–88.

28. See Harry Arthurs, “Confidential Memorandum on Injunctions,” fixed Ontario Department of Labour, RG 3-26, box 189, Premier J. P. Robarts General Correspondence Strikes-Exparte Injunction January 1966–June 1966, Archives of Ontario; A. W. R. Carrothers, Report of a Study on the Labour Injunction in Ontario (Toronto: Ontario Department of Labour, 1966); Canada, Task Force on Labour Relations [Woods Commission], Canadian Industrial Relations: The Report of the Task Force on Labour Relations (Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services, 1968), 185–186.

29. International Labor Organization, Freedom of Association Cases, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:20060::FIND:NO:::. Between 1970 and 2015 there were 25 complaints to the International Labor Organization’s Freedom of Association Committee dealing with back-to-work legislation, all of which originated in Canada.

30. Fudge & Tucker, “Freedom to Strike,” 355.

31. Panitch & Swartz, From Consent to Coercion, 15.

32. “Concessions by Unions 11th-Hour Offer by Railways Fruitless,” Toronto Star, 22 August 1950.

33. Wilfrid List, “Unions Work on New Set of Proposals,” Globe and Mail, 22 August 1950.

34. “Meat Famine Faces North,” Globe and Mail, 22 August 1950; “Starve within a Week, 29,000 in Timmins Fear Ration Gasoline Now,” Toronto Star, 22 August 1950; “300,000 Workers Idle; Toronto Lucky So Far,” Globe and Mail, 24 August 1950; “10,000 Miners Facing Layoff in Sudbury Area,” Toronto Star, 22 August 1950; “1,000 Layoffs Daily in Ontario over Strike; Meat Prices Take Jump,” Globe and Mail, 26 August 1950; “700,000 Unemployed Expected within Week; Ontario Suffers Least,” Globe and Mail, 25 August 1950; “The Power of Life and Death,” editorial, Globe and Mail, 24 August 1950.

35. “Let’s Be In the Poorhouse Together, Says Mosher,” Globe and Mail, 24 August 1950.

36. Irving Abella, Nationalism, Communism, and Canadian Labour (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973), 159. On Mosher’s anticommunism against unions operating on the railway, see the discussion to expel the United Electrical Workers from the ccl in 1949 and 1950 in Abella, Nationalism, 150–163.

37. “Order M.P.’s Flown to Ottawa by R.C.A.F. for Strike Session,” Toronto Star, 22 August 1950; “Arbitration by Law Binding on Both Sides Said St. Laurent Plan,” Toronto Star, 22 August 1950.

38. “Government Plans Ultimatum: Work or Lose Pension,” Globe and Mail, 28 August 1950.

39. “New Law Threatens All: Official Back-to-Work Order Sets Strike-Breaking Pace Rouses All Unionists,” ue News 9, 337, 1 September 1950.

40. Canada, Parliament, Official Report of Debates, House of Commons, 21st Parl., 3rd Sess., Vol. 1, 14–15 George VI (29 August 1950) at 11.

41. Canada, Parliament, Debates, House of Commons (29 August 1950) at 13, 12.

42. “New Law Threatens All: Official Back-to-Work Order Sets Strike-Breaking Pace Rouses All Unionists,” ue News 8, 337 (1950): 1.

43. T. C. Douglas, “Statement for Leader-Post, Re: Back-to-Work Legislation (The Maintenance of Railway Operation Act),” 30 August 1950, Saskatchewan Archives Board, T. C. Douglas fonds, F117, R 33.1, file 810, (31), Press, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.

44. “Five Day, Forty-Hour Week Written into Canadian Law by Militant Railway Unions,” Canadian Railway Employees’ Monthly, September 1950, 284.

45. “President’s Message to All Members of the Brotherhood on Strike, August 22–30, 1950,” Canadian Railway Employees’ Monthly, September 1950, 286.

46. Saskatchewan was the only province to allow its public-sector workers to bargain and strike before 1968. In 1944, the ccf government of Tommy Douglas included public workers in its Trade Union Act.

47. On the role of interest arbitration during a strike, see David Doorey, The Law of Work: Industrial Relations and Collective Bargaining (Toronto: Emond, 2017), 156–157.

48. In 2018 members of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (cupw) walked off the job after repeated attempts to have the employer address excessive hours of work and serious health and safety issues for rural mail carriers. The Trudeau Liberals nevertheless intervened and legislated cupw workers back to work because the government was worried about the strike’s implications for the Christmas retail season. Over two years later, cupw reported that the health and safety issues remained unresolved. “Canada Post Employees Protest in Montreal after 2 Years without Collective Agreement,” cbc News, 31 January 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/canada-post-montreal-protest-1.5447160.

49. Bryan Eneas, “Co-op Refinery Labour Dispute: Unifor Accepts Special Mediator Recommendations, fcl Does Not Accept In Full,” cbc News, 22 March 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/special-mediator-recommendations-fcl-unifor-1.5506135.

50. Consumers’ Co-operative Refineries Ltd., v. Unifor Canada, Local 594, 2020, skqb 38.

51. Jim Warren & Kathleen Carlisle, On the Side of the People: A History of Labour in Saskatchewan (Toronto: Coteau, 2005), 241.

52. Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v Saskatchewan, 2015 scc 4, [2015] 1 scr 245.

How to cite:

Charles Smith et al, “Back-to-Work Legislation Roundtable,” Labour/Le Travail, 86 (Fall 2020), 107–158, https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0040.

Copyright © 2020 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2020.