Labour / Le Travail

Issue 86 (2020)

Research Note / Note de recherche

Remembering 1919: The Winnipeg General Strike

The year 2019 was the centennial of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, the most radical strike in Canadian history. The strike has been examined extensively by protagonists,1 academics,2 writers of fiction,3 documentary filmmakers,4 play/script writers,5 and visual artists.6 Despite this abundance of research, how the strike has been remembered and commemorated by subsequent generations of Winnipeggers has been understudied.

Oral histories of those involved in the strike have been archived, but the intergenerational memory of these people has been largely unaddressed.7 I conducted oral history interviews with six descendants of those involved in the 1919 strike, to learn how stories of the strike have been passed down in their families and how those stories shaped the interviewees’ own understandings of labour and social justice. Conducting and archiving such interviews is important, because (outside of cultures that have strong oral traditions) communicative memory lasts only three generations.8 It is also important because descendants do not always value and preserve family history.

The latter point is illustrated by the story Sheryl Gray shared with me. I had been told that she had married a great-grandson of Herbert Gray, who was a City of Winnipeg alderman at the time of the 1919 strike. She declined an interview with me, however, saying that she didn’t know enough about his actions during the strike, despite her interest in the subject. She explained in an email:

Unfortunately, Dorothy Mathieson, the one person that knew and documented all the family history and stories, passed away 3 years ago. She was Herbert Gray’s granddaughter and had promised to send me her info from her home in Kingston [Ontario], but never did. Sadly, when she died, her son sent all her research and papers to the dump. The only thing that was salvaged from that fiasco was a City of Winnipeg silver letter opener from 1918. Someone had purchased it as part of a lot after Dorothy’s death and made the effort to find our family to return it to us. That opener is our only connection to that time period.9

Stories like this of the loss of family memories, together with stories my brother-in-law had told me of his grandfather’s injuries during Bloody Saturday, prompted me to begin a small oral history project with descendants of those involved in the 1919 strike.

The then upcoming 1919 Winnipeg General Strike Centenary Conference – of which I was a planning committee member – was a strong incentive to record these oral histories. It was important to me that the conference have an oral history component that explored the ongoing impact of the strike on descendants of those who had been involved in it. The Manitoba Federation of Labour posted a call for interviewees on my behalf, as did I on social media. Sharon Reilly, another member of the conference planning committee and former curator at the Manitoba Museum, put me in touch with some potential interview participants as well. A dozen potential participants expressed interest, but only six people (four women and two men) were willing to follow through with an interview. Those who declined, like Sheryl Gray, explained that they had only limited knowledge of their ancestors’ involvement in the strike and thus had nothing more to share in an interview.

Interview participants gave permission for their interviews to be archived with the Oral History Centre at the University of Winnipeg. They were asked versions of the following questions:

- Which relatives of yours were involved in the 1919 strike?

- How were they involved?

- What were the consequences (economic, social, familial) to them of that involvement?

- Did they tell you any stories about that involvement?

- When and how did they share those stories with you?

- What did you feel when you first heard those stories?

- What did you learn from these stories?

- How have those stories shaped your understandings of labour/unions/social and economic justice?

- Have you yourself ever been on strike?

- How has your understanding of your relatives’ stories changed over time?

- How have you preserved and passed on those stories to others?

The interviews were conducted from September through December of 2016, more than three years before the centennial of the 1919 strike. Local media were not yet giving attention to the centennial, but academics and members of labour organizations in Winnipeg were planning well in advance for their own celebrations and commemorations. It is possible that, had I solicited interviews in mid-2019 rather than late 2016, I would have attracted more participants with fewer ties to academia or labour.

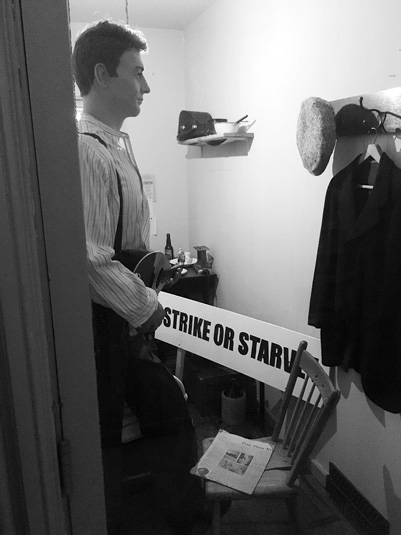

Members of the general public not involved in conference or exhibit planning became more aware of the 1919 strike centennial (or, indeed, of the strike itself, whose history is not always well known even to Winnipeggers) once commemorative events began to be publicized. These events were planned by the Manitoba Federation of Labour, the Winnipeg Labour Council, and various union locals, museums, archives, and universities in Manitoba. They included a revised and expanded edition of the Winnipeg General Strike walking and driving tour booklet,10 a number of bus and walking tours of strike sites,11 a labour arts exhibit at Winnipeg’s Millennium Library,12 a redesign of the Urban Gallery at the Manitoba Museum,13 special musical performances about labour,14 walking tours of Brookside Cemetery (where Mike Sokolowski is buried),15 and the Winnipeg General Strike Centenary Conference.16

Figures 1 & 2. Parts of the exhibit showcasing the 1919 Strike in the Urban Gallery of the Manitoba Museum.

Photos by the author.

Figure 3. Existing buildings in the Manitoba Museum’s Urban Gallery were redesigned as a labour temple and as the Strathcona Restaurant (which was operated as a labour café in 1919 by the Women’s Labour League).

Photo by the author.

These commemorative activities, though held more than three years after the interviews, undoubtedly had an effect on the interview participants and shaped their oral histories. The interviewees were connected to people in the museum world, in academia, in the Winnipeg Labour Council, and in other groups planning centennial events and exhibitions. They had been informed that I would be inviting them to share shortened versions of their stories at the 1919–2019 centennial conference and that their recorded interviews would (with their permission) be archived at the University of Winnipeg. They clearly understood the significance of their oral histories: they would be helping to counter the “[dominant] narratives of the rise of Canadian capitalism and parliamentary democracy.”17

In Canada, events of significance for labour history have not always received the same degree of commemorative attention as other elements of the past. Public commemorations of Canadian involvement in war have tended to attract more government support.18 It is only in the 1980s, Cecilia Morgan reminds us, that school curricula and textbooks began to be more attentive to “conflicts between labour, the state, and capital,” moving beyond their traditional presentation of Canadian labour as “peaceful, temperate, and, above all, complacent.”19

In the excerpts from the oral histories that follow, it is clear that family memories and political consciousness interact with each other and develop over time. An ongoing tension exists between collective memory – the “common past, preserved through institutions, traditions, and symbols”20 – and individual and familial memory. Oral historian Alistair Thomson argues that “oral history can help us to understand how and why national mythologies work (and don’t work) for individuals, and in our society generally. It can also reveal the possibilities, and difficulties, of developing and sustaining oppositional memories.”21 For the descendants of those involved in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 who I interviewed, this was apparent. Some (Tom Paulley, Lisa McGifford, and Sandra Oakley) used their ancestors’ stories to craft a personal narrative of progressive politics and labour activism. Others (Margaret Owen, Kathleen Christensen, and Ross Metcalfe) had a more conflicted understanding of their ancestors’ lives.

Several participants at the Winnipeg General Strike Centenary Conference observed a willingness on the part of Winnipeggers to reflect at the 100th anniversary in a way that had not happened at earlier anniversaries of the strike. And yet these six oral histories reveal that while descendants of those involved in the 1919 strike may be more willing to discuss the strike now that it is a few generations removed, some aspects of the strike are still underdiscussed. Most interview participants were willing to speak of how their own understandings of labour and social justice were shaped by stories of family members involved in the strike. But their discussion was limited in terms of the role of the strike in the broader history of capitalist expansion – and was nonexistent when it came to the place of the strike in the history of Indigenous dispossession.

Lisa McGifford comes from a strong labour tradition, which has influenced both her professional choices and her understanding of her relatives’ memories of 1919. She is executive director of the University of Winnipeg Faculty Association (uwfa). She worked in community health for some time before getting a law degree and then coming to work at uwfa. Her mother, Diane McGifford, was an ndp mla in Manitoba from 1995 to 2011 and also worked as a university professor. Diane was involved in various forms of activism and introduced Lisa to that world, as Lisa recalled.

There was a strike at the University of Manitoba. It was cold and raining and fall … and we took soup to the strikers. And she [Diane McGifford] wouldn’t cross the picket line to teach her course, which … she was a grad student at the time, so you know, how you teach to eat. She didn’t cross the picket line as I am sure the employer would have liked her to do. So, that was really the way in which I became aware of unions.22

These experiences were part of the reason Lisa went to law school; she felt that “workers needed better representation than what was available to them.”23

Lisa McGifford’s great-grandfather, James McGifford, went out on strike in 1919; his son Bob was about ten years old at the time. James “was friends with everyone who was involved with organizing of the Winnipeg General Strike.”24 Another great-grandfather, John Fifer, was also a striker in 1919 and apparently lost his job at Canadian Pacific (cp) Railway as a result.

James McGifford had a friend who was a Webster. I don’t know what the first name was. But my grandfather was friends with Jack Webster and Jack Webster was also Scottish. This mattered then, as people hung out with their groups, right? But Jack was Catholic, and my grandfather was a Presbyterian. They didn’t always see eye to eye, but being immigrants kind of transcended that particular divide, and they were very close friends from the time that they were seven years old. And they went along with the strikers, and one of the things that they and the other bunch of kids found – boys, I am sure – was a boxcar full of goods that were destined for the mayor of Winnipeg. They broke in. [laughs] And the thing that they found there among other things was bananas, and they had never seen bananas before. They knew that they could eat them, so they ate them, and were violently ill as a result because they ate A LOT of bananas. [laughs] And Jack grew up then to become a chief of police in the city of Winnipeg, which was kind of unheard of because of him being Catholic. And my grandfather became the chief electrical inspector. My grandmother’s father, John Fifer … now I don’t know if this is true, but I had heard when he went on strike, he was fired as a result of it. Then to get rehired at cp [Railway], he had to give a different name other than the one that he had, so I guess he made one up, if it’s true. And that presented problems for him. My great grandmother, later when he died, and she wanted the pension benefit he had – but as I say, I don’t know if that is true.25

Lisa’s remarkable anecdote is a dense reflection on several aspects of working-class history. She comments on the shared ethnic identity of her grandfather and his friend, a friendship that transcended religious differences that were often a barrier at that time. Inter-ethnic and inter-religious alliances were significant during the strike, but here she gives an example of one that predates 1919. And her story about bananas reveals both the difference in perceptions of the strike between adults and children and the stark divergence in diets between the working class and the élite at that time.26 Her adult great-grandparents’ memories of the strike emphasize the consequences for employment and pensions; her grandfather, a child at the time, was more struck by a dramatic first experience with exotic fruit. It is perhaps because he was a child at the time of the strike that her grandfather, as an adult, took a mixed view of politics.

My grandfather had this very strange political approach where municipally he voted Communist and then at other levels of government he voted Conservative. He thought that Joe Zuken was the best thing that ever happened, but he voted for Brian Mulroney [laughs].27

It is interesting to observe that at the local level, which arguably affected him most intimately, he chose to support Communist candidates. Presumably his childhood experience of class differences had an ongoing effect.

Sandra Oakley’s parents both worked for Winnipeg Hydro, and her father was an activist in cupe Local 500; she became aware of unions through him. She worked for Manitoba Hydro, where she became very active in cupe, working for the union for more than three decades. She learned much about her grandfather and his attitudes toward labour through contact with those who had worked with him. She observed of her own union involvement that it “seemed to me a logical thing to be involved in, right? It opened lots of doors for me as a woman.”28

Sandra Oakley’s grandfather, Alexander Milne Oakley, was a striker in 1919. He was from Scotland, originally, and also worked in South Sudan before moving to Canada and working with Hydro. Sandra’s father was a labour activist, although the strike did not affect him personally. Sandra recalls that her grandparents’ memories of the strike shaped her childhood.

Scots have long memories. Telling me I shouldn’t play with the kid down the street because his grandfather crossed the picket line in 1919. Now, when I was five, I probably wasn’t as rigid about picket lines, and besides, he had a better sandbox! But, that kind of stuck in my mind when my grandmother said that, and you know, as I grew older, I understood that. Because even though they were citizens, they could’ve been deported, and she was pregnant with my father, my father was born in October. So, that must’ve been a pretty scary time, uh, for her in particular. Plus, they had one child, my Aunt Dora. But as I say, he [my grandfather] eventually got his revenge because he worked his way up and when he retired he was superintendent of the transmission for Winnipeg Hydro – at that time it would have been called City Hydro.29

Like Lisa McGifford, Sandra learned about class differences and class solidarity at an early age: two generations after the strike, she was taught not to play with the grandchildren of strikebreakers. Unlike Lisa’s great-grandfather John Fifer, however, Sandra’s grandfather seemingly didn’t face any negative consequences for striking in 1919.30 On the contrary, his individual upward mobility is interpreted here by Sandra as revenge for the wrongs suffered collectively by the strikers.

Margaret Owen is a Winnipeg author and retired schoolteacher. When she was a child, her mother, uncles, aunts, and cousins shared stories of her labour activist grandfather William Cooper. She recalls they were “very much in awe of him, but they thought he was pretty cranky, too.”31 She has collections of the column he wrote for the Winnipeg Tribune, which her children have read. Her oldest son, who wrote an article about Cooper for the Winnipeg Free Press, “really admired” him, as does one of her granddaughters. Margaret was quite clear throughout her interview that she did not share her grandfather’s radical views.

William Cooper was a radical socialist who influenced the 1919 strikers. Originally from Scotland, he immigrated to Canada in 1905 and found work with the Canadian National Railway. During the 1919 strike, he ran a “workers’ university,” where he taught socialist theory.

My grandfather, I never really knew him, but I knew an awful lot about him, so that is my interest. He was a mentor to several of the strike leaders, and he didn’t actually – well, he didn’t take part in the strike. But names like John Queen, R. B. Russell, and [R. J.] Johns, and who is the other one? They were forefront, and they were the ones that were jailed for sedition. Now, my grandfather wasn’t, because he sort of just stayed in the background, but he ran what he called a “workers’ university” in one of the labour temples. I thought that there was only one labour temple, but apparently, there was another one in the south end of the city. Anyway, I don’t know which one it was. On Thursday afternoons, he taught socialist theory to all of these people who ended up being strike leaders, so he was quite a character.32

Cooper supported the One Big Union and wrote prolifically on labour issues, educating the working class in the philosophies that undergirded the labour movement. He was one of many lesser-known figures in the strike whose advocacy, organizing, and intellectual abilities helped spread and sustain it.

He wrote for the One Big Union bulletin. As [historian] Jack Bumsted said, he was the one that really spread [the idea of the obu] – because in Britain at that time, the labour union was very strong, and he had organized a carpenters’ union in Aberdeen before he ever came here. Like, he was really rabid about the working man and really hostile toward the establishment and he, umm, he said some terrible things, you know. [laughs] But, they are funny in retrospect. But yes, he decided that he was going to spread his philosophy, the socialist philosophy, and so, he was really one of the people that brought it to Winnipeg. … He abhorred the [Winnipeg] Free Press. … He had abhorred the Free Press and he called it “that hideous outrage on Carlton Street run by money thugs devoted to economic falsity, anti-social justice, political perversity, and hate between the working classes.”33

Margaret’s mother and other family were quite proud of Cooper and passed down stories about him. As mentioned above, her son wrote an article about him for the Winnipeg Free Press, from which she quoted at times during her interview.34 She also read from Cooper’s own writings. Margaret herself, however, does not share her grandfather’s views.

He said [the One Big Union was] an organization based on class lines and any attempt to organize the workers on a class basis must, in its nature, be political, like you can’t separate the two. He was very adamant about that. It touches the root principles of the struggle of the working class to obtain power and he felt that the working class should have all the power. You know, because they did all the work. … So, it was Cooper’s belief that the master class should be put down, the working class should be in control of the economy. Like, he really, really believed this, that they were the only ones that knew, you know, and I think he thought a lot of these people who had a lot of money and owned – but you know, as I was saying, somebody had to own these companies, so that these workers could have jobs. That’s my philosophy. His philosophy was that they were doing all of the work and that the people who run them are idiots, they didn’t know anything, so they should be put in their place. But, I don’t know. I didn’t agree with everything that he said or believed. [laughs] But I can understand why he did because the times were different then. He said that [reading] “The position is, therefore, that we have to use our organization to secure the conquest of political power in order that the control of industry shall be brought into our own hands. The object set before us in the obu is altogether different than that of any international or old-time craft or trade union. It was essentially of a class character and will undoubtedly involve political as well as industrial conflict.” And you know, I don’t think that the class system is ever going to go away. It’s there. But, he wanted to reverse it. He wanted to be … he wanted the workers to be in charge of the world. Yeah, that was his philosophy. [reading] “He was extremely hostile toward the wealthy and saw no possible way to close the gap. He worked towards the idea that the men and women who did the work of the world had anything in common with those whose income grows while they sleep is one of the illusions of what is the main purpose of obu to dispel.” Yeah, so, you know, he … it’s a definite, umm, it’s a philosophy. Yeah.35

As Margaret makes clear in this excerpt from her interview, she did not support her grandfather’s class analysis. She identified far more strongly with her father’s story, about which she has written a book.36 Her father, Victor Dennis, had been a Winnipeg Grenadier during World War II. He was sent overseas in 1941; his family were not permitted to know the destination, which was “a terrible experience.” He returned in very poor health and died from a lung tumour; his devastated wife, Margaret’s mother, had a heart attack shortly thereafter and died a few months later. Perhaps this dreadful experience explains Margaret’s approach to her grandfather’s story and politics, which were neither as immediate nor as personal.

Kathleen Christensen, curator of the Royal Canadian Artillery Museum, began asking her grandmother about her memories of the general strike after she became interested in history. She had done some research on the general strike in her work creating museum exhibits. The family as a whole has always been interested in politics, and several family members have been supporters of the New Democratic Party, perhaps as a result of her great-grandfather Robert’s political involvement, she speculated. She herself once attended an ndp convention in Brandon:

One of the proposals was that the Manitoba Government apologize to the family of the 1919 strikers and those who were blacklisted. It was way down with other ones that, anyways, that was on the … 90th anniversary. So, it didn’t happen. I was taking it personal at the time and thinking about whether I could accept their apology. It never got to the floor and I don’t imagine that that’s going to occur. There have been so many apologies that they are almost losing their edge, but that would be interesting.37

Kathleen Christensen’s great-grandfather, Robert Stewart, was involved in the 1919 general strike. Robert had emigrated from Scotland in 1912, when his daughter (Kathleen’s grandmother) was two years old. He became a firefighter; his brother, Charles Stewart, was also a firefighter in Winnipeg. Kathleen’s grandmother, Barbara Ann Stewart, recalled going to rallies with her father in Victoria Park. Robert was downtown on Bloody Saturday (this time without Barbara); he was uninjured by the troops and Specials. Robert often had trouble finding work after the strike, and his wife had to provide financially for the family. He was a self-described socialist/communist and blamed blacklisting for his inability to get work; family members recalled him becoming very bitter.

There’s just that sort of undertone of a lot of bad luck and that he chose or made some bad choices and didn’t think of the consequences on the family when he, you know, got so involved in the strike. And maybe was too vocal afterwards and burned some bridges, so maybe it was that and not the blacklisting, but he always blamed the blacklisting for his inability to get good work. But that is sort of a nefarious thing, you know, that blacklist wasn’t a piece of paper that people handed around.38

Robert eventually found work with cp Railway. Kathleen concluded her interview with the following reflection:

There is one more thing that I could say. The history that I have with my family on both sides because I have stories on both sides, you know, always talking to family on both sides, my grandmother primarily; both of them generated in me a love of history. You know, a love with those family stories. You know, it’s true that because of the influence of both of them that it did affect my politics, you know, I guess my feelings towards unionism, but it more affected my view of the importance of history and to go into that career and to make sure that these types of stories are kept. And that is partly why I am participating in this [interview], you know, it is professional, and it is personal. I’ve always had that combination. My interest in history has always been both – well, it started as personal, and then it became professional, rather than my politics.39

The lesson Tom Paulley took from his grandfather Les Paulley was that unions were essential in both 1919 and the present day. Of those I interviewed, he was the most mindful about the connections between his family and personal history and the history of the 1919 strike. He believes that “the wealth that workers produce has to be shared more equitably” than it is now or was in 1919.40 His grandfather’s stories “confirmed in my mind a lot of what at that time I’d been reading and thinking about” regarding economic inequality and “how to level the playing field a bit more.”41 Tom responded by obtaining a master’s degree in political studies and running for office. He ran in the Winnipeg civic election in 1977 as an ndper, finishing second in a field of four. He ran federally for the ndp in 2011, finishing second with 20 per cent of the vote, and ran again, unsuccessfully, in 2015.

Tom Paulley’s grandfather, Leslie (Les) Paulley, was seventeen and working as a telegraph courier for the cp Railway in 1919. He had emigrated with his parents from England at age seven or eight. Les ran for the Independent Labour Party for school trustee in the 1920s, was a member of the Left Book Club in the 1930s, and took public speaking lessons from J. S. Woodsworth.

During his interview, Tom shared a couple of his grandfather’s documents with me: a letter regarding the origins of the Labour Church in Winnipeg, and Les Paulley’s written summary of the events of the 1919 strike. At a time when many of the elites in the city’s Anglo-Protestant churches were preaching against the strike, the Labour Church offered Winnipeg’s workers an alternative interpretation of the Christian gospel. Les Paulley explains the Labour Church’s origins and significance in an undated letter:

The Labour Church would never have come into being had it not been for the persecution and final expulsion of the Rev. William Ivens from the pulpit of McDougall Memorial Methodist Church [formerly located on Main north of Higgins]. Mr. Ivens was a brilliant platform speaker and at times his addresses touched the border of pure oratory. I respected and admired him greatly and although often feeling somewhat irritated by his many manifestations of egotism concluded that this characteristic might well be essential to those who felt impelled to assume leadership roles. In any event Mr. Ivens was an unabashed pacifist who detested violence in any form. Toward the end of World War One he thundered his denunciations of war profiteers and such from the pulpit of McDougall Church and included in his castigations the Scribes and Pharisees and money-changers within the Temple. Without in any sense becoming a Marxist he clearly recognized the class divisions obtaining in Canadian society and felt the answers to all the world’s problems could mainly be found in the social gospel of Jesus Christ. He acted in full accordance with all that this implied. No stretch of the imagination is required to see that he soon became regarded by the “Establishment” as a menace. He had to go.42

Rev. Ivens’ departure led to the formation of the Labour Church, and as it “rapidly began to flourish the decline of McDougall Methodist was equally rapid.”43 The Labour Church “reached the zenith of its development” in the 1919 strike: branches sprang up in Weston, Fort Rouge, West Kildonan, Morse Place, Elmwood, and the West End.44 Regarding the 1919 strike itself, Les wrote,

It was simply the unified effort of thousands of men and women, few of whom were students of history or social science, to achieve their objectives by the peaceful withdrawal of their labour-power from the industrial market. … Opinions may well differ, but it remains true that the strike was the finest manifestation of working class unity, courage and resoluteness ever to appear in the history of our country and that it was led by noble men who, with all their faults and weaknesses, imperishably inscribed their names upon the scarlet banner of human liberty.45

If Tom Paulley’s oral history was the most fervently supportive of the 1919 strike and its role in his personal politics, Ross Metcalfe’s oral history was the most conflicted. He described his family’s extensive involvement in the economic development of the city of Winnipeg.

Because my grandfather was involved with the real estate thing [as president of the Winnipeg Real Estate Exchange and owner of land that became the Winnipeg suburb Wildwood Park], he also brokered all of the deals with the Shoal Lake Aqueduct, so you will see his pictures in Shoal Lake Aqueduct stuff as part of the St. James Pumping Station sale. So, he’ll be the guy with the derby hat representing the government in that thing. I think back to a time when we don’t seem to have any money – yeah, well, it was growing and there was an economic boom there. Like, I keep thinking that they built this Union Bank Building, the biggest skyscraper in the British Empire, and they have an aqueduct that could service the needs of about ten times the amount of the population than was required, but I think we’ve lost some of that planning for our future in the current generation. We speak a good game about global warming and protecting our wildlife, but we don’t go at it in a big way. We don’t bite the real bullet on the real cause. These guys built an aqueduct, I think there might have been 80 or 90 or 100 thousand people here and this pipe could serve 1 million people by water or something.46

Though he described his family’s involvement in land deals and the water supply, he did not connect his family’s history to the history of dispossession of Indigenous peoples in Winnipeg and at Shoal Lake. Nor did I question him about this: Adele Perry’s Aqueduct had been published only a few months before this interview, and I had not yet read it, unfortunately.

Ross Metcalfe’s great-uncle was Justice Thomas Llewellyn Metcalfe, who tried the 1919 strikers. His grandfather’s family lived near the judge, and his father was a young teen during the trials. “The judge lived at 461 Wardlaw. My grandfather built a house at 435 Stradbrook. … They were only 100 metres away and could huck a rock across the street.”47 The family had to have guards escort them to and from school because of threats received by the judge.

And during the general strike, the judge had no children and my grandfather had five, and death threats were sent to the judge during the trials. … So the federal government hired Pinkerton guards from Minneapolis. And for the entire time of that strike, my dad and his sisters were walked to and from school every day by Pinkerton guards from the United States, and a Pinkerton guard was outside their house at 435 Stradbrook.

Ross believes that Justice Metcalfe has been depicted unfairly in history books and that he was a fair and extremely diligent judge who wanted to help the strikers while still following the letter of the law. His father and his father’s siblings would walk over to the judge’s house when they saw the lights on late at night there.

The judge would be laid out on the floor fast asleep with law books all over the floor, and they’d wake him up and say, “Tom, you have to be in court tomorrow. You’ve got to get yourself into bed.” And this is a quote [from my grandfather] that I will never forget. “He looks up at his brother and us and he says, ‘I’ve got to find a way to get these poor bastards off.’” And that was the line. I’ve got that. “I need to find a way to get these poor bastards off.”

Through this quote, Ross offers a new, more favourable interpretation of the actions of the judge who tried the strikers, portraying him here as a labour sympathizer. Ross further aligns the Metcalfe family with the strikers in his discussion of employment implications: the name Metcalfe caused trouble for some of his family members following the strike. In 1926, his father was about to be hired for a job as an accountant but, when asked if he was any relation to Justice Metcalfe, was told, “No Metcalfe will ever work in this firm.” Family members were reluctant to discuss the strike for decades, Ross recalled.

My aunt Marion and my father – who is Thomas Hatten Metcalfe, named after his grandfather, ironically – umm, they sure didn’t want to talk about the Winnipeg General Strike until about 50 years later when I am studying in university. I had to pry it out and then, all of the sudden, my father said, “This is silly. Here, look at this [scrap]book. My mother made this book.”

In a session dedicated to these oral histories at the Winnipeg General Strike Centenary Conference, Ross recounted that the judge became seriously ill shortly after the trial, and that as he was dying, he asked strike leader R. B. Russell to see him. Paul Moist, former cupe president, was a member of the audience at this session, and he recalled that Russell’s secretary had mentioned something about this in her memoirs:

Bob Russell was to retain a bitter kind of compassion for Judge Metcalfe all his life.

“The scales of justice must weigh this evidence and judge this evidence. I have no choice,” said the judge.

Judge Metcalfe pronounced the sentence:

“Two years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary.” “Go home for Christmas.”

Bob was given Christmas Day to spend with his family. What Judge ever before pronounced sentence upon a convicted criminal guilty of seditious conspiracy, and then said “Go home…”?

…

When he was dying Judge Metcalfe sent for Bob Russell, he had something to say to him.

“No,” said Bob Russell, “I will not go. I think I know what he wants to say. I could not go. Let him die with his guilty conscience.”

After the death of Judge Metcalfe it was Bob Russell’s turn to be conscience-stricken.

“I was sorry. I will always be sorry,” he said.

He never quite forgave himself that he could not make himself go; that he had refused the last request of the dying Judge.48

Ross’s oral history emphasized the reluctance of his ancestor to judge the strike leaders, the negative consequences for employment of some of his family members, and the judge’s deathbed efforts to restore a relationship with at least one strike leader. In so doing, Ross created a familial narrative of strike-related suffering that gave an impression of allyship for his family with those of the strikers’ descendants.

Though comprising a limited sample, these six interviews with descendants of individuals involved in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 are revealing. They demonstrate the differences between children’s and adults’ perceptions of the strike, as in the cases of Lisa McGifford’s and Sandra Oakley’s ancestors. They highlight the importance of less well-documented personalities in the history of the strike, as in the cases of Margaret Owen’s and Tom Paulley’s ancestors. They reveal that, while significant events like the 1919 strike may affect descendants’ career choices and political views, they need not be determinative; people like Margaret Owen may admire their ancestors while also rejecting their views. Finally, as I noted in the introduction, these interviews attest to the importance of memory (both individual and collective) in oral history and, subsequently, in labour history. This small project is part of a much longer trajectory of work by labour historians who use oral histories and strikes to examine memory, the lived experiences of workers, and the history of the labour movement.49 Oral histories like these help historians understand how individual and family memories shape and are shaped by collective memory and its national commemoration. They also, as Jonathan Moss reminds us, “offer individuals the opportunity to share their concerns and uncertainty over public memories.”50

With the centennial of the Winnipeg General Strike in 2019, we saw an increased willingness on the part of government to publicly commemorate the strike within Winnipeg.51 The 1919 Marquee, an installation of weathered steel and lights that incorporates a map and history of the strike, was erected on Lily Street at Market Avenue (near the former site of the James Street Labour Temple).52 The 1919 Streetcar, an evocation of the streetcar that was tipped and burned during Bloody Saturday, was placed at Market Avenue and Main Street, directly across from City Hall.53 A plaque in the basement of the Centennial Concert Hall, commemorating the James Street Labour Temple and for some time lost in storage, has been relocated and will be placed in a more prominent location.54 These public displays are all the more important in light of the dismantling of the strike exhibit that was the recreation of Room 10 of the James Street Labour Temple at the Canadian Museum of History.55 Yet labour supporters would do well to remember Cecilia Morgan’s warning that “communities that now insist on their inclusion in the commemorative landscape can also fall prey to the allure of simplistic and celebratory histories that gloss over internal conflicts, ignore complexities, or downplay less-appealing aspects of their pasts.”56 As newspaper editorials and conference papers reveal, a reluctance to discuss 1919 strike history in the context of colonial history persists.57 Though much about the strike has been researched, much more remains to be done.

My thanks to the anonymous reviewers, and to editor Joan Sangster in particular, for their many helpful comments and suggestions.

1. Defense Committee, The Winnipeg General Sympathetic Strike, May–June 1919 (Winnipeg: Defense Committee, 1920); William A. Pritchard, W.A. Pritchard’s Address to the Jury (Winnipeg: Defense Committee, 1920); Frederick John Dixon & Alexander Galt, Dixon’s Address to the Jury in Defence of Freedom of Speech (Winnipeg: Defense Committee, 1920); Norman Penner, ed., Winnipeg 1919: The Strikers’ Own History of the Winnipeg General Strike. (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1975).

2. Donald C. Masters, The Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1950); J. E. Rea, The Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1973); Kenneth McNaught & David Bercuson, The Winnipeg Strike, 1919 (Don Mills, Ontario: Longman Canada, 1974); Irving M. Abella, On Strike: Six Key Labour Struggles in Canada, 1919–1949 (Toronto: James Lewis & Samuel, 1974); A. R. McCormack, Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement, 1899–1919 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977); David Jay Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg: Labour, Industrial Relations, and the General Strike (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990); J. M. Bumsted, The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919: An Illustrated History (Winnipeg: Watson & Dwyer, 1994); Harry Gutkin & Mildred Gutkin, Profiles in Dissent: The Shaping of Radical Thought in the Canadian West (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1997); Craig Heron, The Workers’ Revolt in Canada, 1917–1925 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998); Jack Walker, The Great Canadian Sedition Trials: The Courts and the Winnipeg General Strike, 1919–1920 (Winnipeg: Legal Research Institute of the University of Manitoba, Canadian Legal History Project, 2004); Reinhold Kramer & Tom Mitchell, When the State Trembled: How A. J. Andrews and the Citizens’ Committee Broke the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010); Stefan Epp-Koop, We’re Going to Run This City: Winnipeg’s Political Left after the General Strike (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2015); Dennis Lewycky, Magnificent Fight: The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike (Halifax: Fernwood, 2019).

3. Gail Bowden & Ron Marken, 1919: The Love Letters of George and Adelaide (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1987); Douglas Durkin, The Magpie (Toronto: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923); Margaret Sweatman, Fox (1991; Winnipeg: Turnstone Press, 2017); Allan Levine, The Bolshevik’s Revenge (Winnipeg: Great Plains, 2002); Ron Romanowski, Insurrection (Winnipeg: Augustine Hand Press, 2009); C. M. Klyne, The Silent March (Altona, MB: Friesens, 2013); Ruth Latta, Grace and the Secret Vault (Ottawa: Baico, 2017); Richard Zaric, Hiding Scars (Brockville, ON: Sands Press, 2018); Harriet Zaidman, City on Strike (Markham, ON: Red Deer Press, 2019); Melinda McCracken with Penelope Jackson, Papergirl (Halifax: Fernwood, 2019); Ron Romanowski, If 30,000 Strikers Marched Today (Winnipeg: Augustine Hand Press, 2019).

4. On Strike: The Winnipeg General Strike, 1919, directed by Joe MacDonald & Clare Johnstone Gilsig (National Film Board of Canada, 1991); Telling Our Stories: Winnipeg 1919, directed by Terry Kennedy (Manitoba Labour Education Centre, 1994); Six Weeks of Solidarity: Winnipeg 1919, directed by Victor Dobchuk, written by Doug Smith (Manitoba Labour Education Centre, 1994); The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong, directed by Paula Kelly (Buffalo Gal Pictures, 2001); Bloody Saturday: The Winnipeg General Strike, directed by Andy Blicq (cbc Learning, 2007).

5. Geoffrey Bilson, Goodbye Sarah (Toronto: Playwrights’ Union of Canada, 1981); Jack Gray, Striker Schneiderman (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973); Ann Henry, Lulu Street (Toronto: Playwrights Co-op, 1972); Danny Schur & Rick Chafe, Strike! The Musical (Toronto: Playwrites Canada Press, 2007), http://www.strikemusical.com; Stand! (Boomtalk Musical Production & Frantic Films, 2019), http://stand-movie.com/.

6. Robert Kell’s Winnipeg General Strike series of paintings debuted in Winnipeg in 1985. Sharon Reilly, “Robert Kell and the Art of the Winnipeg General Strike,” Labour/Le Travail 20 (Fall 1987): 185–192.

7. See interviews recorded in 1969 in the David Jay Bercuson fonds, MG31-B7, R719-0-8-E, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter lac); interviews recorded in 1971–72 in the Michael Dupuis fonds, MG31-B10, R6094-0-3-E, lac; interviews recorded in 1963–70 in the David Millar fonds, MG31-B6, R5813-0-3-E, lac. Excerpts of 23 interviews about the strike held by the Manitoba Museum were made available in 2011 as part of the Winnipeg General Strike 1919 Educational Kit, which was distributed to all schools in Manitoba.

8. Jan Assmann, Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

9. Sheryl Gray, email message to author, 5 December 2016.

10. Gerry Berkowski & Nolan Reilly, 1919, The Winnipeg General Strike: A Driving and Walking Tour (Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation, 1985); Nolan Reilly & Sharon Reilly, 1919, The Winnipeg General Strike: A Driving and Walking Tour (Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage, and Recreation, 2019).

11. “Strike! The Walking Tour,” Exchange District Business Improvement Zone, throughout summer 2019; “1919 Sympathetic Strike Tour,” Paul Moist, 26 May 2019; 1919 strike tour by AESES, 8 June 2019; 1919 strike tour at Doors Open Winnipeg, 26 May 2019.

12. “Robert Kell: Art of the Winnipeg General Strike” was exhibited at the Millennium Library’s Blankstein Gallery in May 2019.

13. “Strike 1919: Divided City” was exhibited at the Manitoba Museum from 22 March 2019 to 5 January 2020, https://manitobamuseum.ca/main/exhibition/strike-1919-divided-city/.

14. Solidarity Forever Community Concert, presented by ufcw Local 832 and cupe Manitoba, 25 May 2019; Rise Up 100: Songs for the Next Century Concert, presented by MGEU, 8 June 2019.

15. Brookside Cemetery Tours by Paul Moist, 26 May and 22 June 2019.

16. “Building a Better World: 1919–2019,” conference website, https://1919-2019.com/. For critiques of the lack of acknowledgement of the connection of Indigenous peoples to the strike, see Niigaan Sinclair, “Racism Intertwined with 1919 Strike,” Winnipeg Free Press, 14 June 2019, https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/strike100/racism-intertwined-with-1919-strike-509936292.html; Adele Perry, “In the Water: The Strike, Shoal Lake and Indigenous Dispossession,” Winnipeg Free Press, 15 June 2019, https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/strike100/in-the-water-511305892.html. See also Adele Perry, Aqueduct (Winnipeg: arp Books, 2016); Graphic History Collective & David Lester, 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2019); Owen Toews, Stolen City: Racial Capitalism and the Making of Winnipeg (Winnipeg: arp Books, 2018); Evelyn Peters, Matthew Stock & Adrian Werner, Rooster Town: The History of an Urban Métis Community, 1901–1961 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2018).

17. Cecilia Morgan, Commemorating Canada: History, Heritage, and Memory, 1850s–1990s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 161.

18. Morgan, Commemorating Canada, 102. See also, for example, government attention to the centennial of the battle of Vimy Ridge (1917–2017) and the sesquicentennials of Canadian confederation (1867–2017) and the founding of the province of Manitoba (1870–2020): Veterans Affairs Canada, “100th Anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge,” https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/first-world-war/vimy-ridge/100-anniversary; Government of Canada, “Canada 150,” https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/anniversaries-significance/2017/canada-150.html; Manitoba 150 Host Committee, “Manitoba 150,” https://manitoba150.com/en/home/.

19. Morgan, Commemorating Canada, 164.

20. Peter Seixas, “Introduction,” in Peter Seixas, ed., Theorizing Historical Consciousness (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 5.

21. Alistair Thomson, “Anzac Memories: Putting Popular Memory Theory into Practice in Australia,” in Robert Perks & Alistair Thomson, eds., The Oral History Reader, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2016), 352.

22. Lisa McGifford, interview by the author, Winnipeg, 20 September 2016, audio recording, University of Winnipeg Oral History Centre (hereafter uw ohc).

23. McGifford, interview.

24. McGifford, interview.

25. McGifford, interview.

26. Non-local fruit remained a luxury item for working-class Canadians at least into the 1930s. My father, born in 1925, recalled his amazement on encountering his first orange as a small boy – a Christmas present from a neighbour.

27. McGifford, interview.

28. Sandra Oakley, interview by the author, Winnipeg, 20 September 2016, audio recording, uw ohc.

29. Oakley, interview.

30. See also Sharon Reilly’s account of a Winnipeg firefighter who was not reinstated and subsequently lost his pension, and Doug Smith’s claim that 3,500 strikers lost their jobs in the aftermath of the strike. Darren Bernhardt, “Winnipeg General Strike Was ‘Large and Difficult Defeat’ in 1919 but Benefits Workers Today,” cbc Manitoba, 18 May 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-general-strike-legacy-1.5137684.

31. Margaret Owen, interview by the author, Winnipeg, 24 November 2016, audio recording, uw ohc.

32. Owen, interview.

33. Owen, interview.

34. Bruce Owen, “Angry Voice Faded Away,” Winnipeg Free Press, 15 May 1994, D9. Courtesy of Margaret Owen.

35. Owen, interview.

36. Margaret Owen, The Home Front: Hopscotch and Heartache while Daddy Was at War (Winnipeg: Heartland Associates, 2011).

37. Kathleen Christensen, interview by the author, 29 September 2016, audio recording via Skype, uw ohc.

38. Christensen, interview.

39. Christensen, interview.

40. Tom Paulley, interview by the author, Winnipeg, 13 September 2016, audio recording, uw ohc.

41. Paulley, interview.

42. Leslie Paulley to “Mrs. Fast,” n.d. Courtesy of Tom Paulley.

43. Paulley to “Mrs. Fast.”

44. Paulley to “Mrs. Fast.”

45. Leslie Paulley, “The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919,” unpublished manuscript, n.d. [c. 1969–72]. Courtesy of Tom Paulley.

46. Ross Metcalfe, interview by the author, Winnipeg, 1 December 2016, audio recording, uw ohc.

47. Metcalfe, interview.

48. Mary V. Jordan, Survival: Labour’s Trials and Tribulations in Canada (Toronto: McDonald House, 1975), 153–154.

49. See, for example, John Bodnar, “Power and Memory in Oral History: Workers and Managers at Studebaker,” Journal of American History 75, 4 (March 1989): 1201–1221; Emily Honig, “Striking Lives: Oral History and the Politics of Memory,” Journal of Women’s History 9, 1 (Spring 1997): 139–157; Joan Sangster, “Telling Our Stories: Feminist Debates and the Use of Oral History,” Women’s History Review 3, 1 (1994): 5–28; Jonathan Moss, “‘We Didn’t Realise How Brave We Were at the Time’: The 1968 Ford Sewing Machinists’ Strike in Public and Personal Memory,” Oral History 43, 1 (Spring 2015): 40–51.

50. Moss, “‘We Didn’t Realise,’” 42.

51. Darren Bernhardt, “‘Lingering Hostilities’ Blamed for Lack of 1919 Winnipeg Strike Monuments,” cbc News, 19 May 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/1919-winnipeg-general-strike-monuments-1.5128440.

52. Monteyne Architecture Works, “1919 Marquee – A Monument,” n.d. [2019], http://www.mont-arc.com/projects/display,project/84/1919-marquee-a-monument.

53. Darren Bernhardt, “100th Anniversary of Winnipeg General Strike Will Be Marked with Monument, Movie, Books,” cbc News, 19 May 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/1919-winnipeg-general-strike-centenary-1.4669345.

54. Keith Hildahl (former chair of Manitoba Centennial Centre Corporation), email and phone conversation with author, 24 and 27 May 2019.

55. “Meeting Room No. 10, Winnipeg Labor Temple,” Canada Hall, Canadian Museum of History, https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/phase2/mod4e.html; Mia Rabson, “Winnipeg General Strike Is Out: Federal Museum Dumps Exhibit of Seminal Event,” Winnipeg Free Press, 26 May 2015, https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/winnipeg-general-strike-is-out-304963481.html; Joanna Smith, “Museum of History to Exclude Winnipeg General Strike Exhibit,” Toronto Star, 22 May 2015, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2015/05/22/museum-of-history-to-dismantle-winnipeg-general-strike-exhibit.html.

56. Morgan, Commemorating Canada, 184.

57. Sinclair, “Racism Intertwined”; Perry, “In the Water”; Adele Perry, “Labour Politics, Municipal Water, and Indigenous Dispossession in Winnipeg, 1919,” and Owen Toews, “Racial Capitalism, Settler Colonialism, and the Conquest of the Strike,” papers presented at the Winnipeg General Strike Centenary Conference, 9 May 2019.

How to cite:

Janis Thiessen, “Remembering 1919: The Winnipeg General Strike,” Labour/Le Travail 86 (Fall 2020): 159–176, https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0044.

Copyright © 2020 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2020.