Labour / Le Travail

Issue 87 (2021)

Article

Corvée Labour and the Habitant “Spirit of Mutiny” in New France, 1688–1731

Abstract: The article examines the evolution of Canadian corvée labour in the late 17th- and early 18th-century French Empire. In New France, tenants, referred to as habitants, rented land from seigneurs in exchange for several taxes. The labour tax, or corvée, required habitants to work on their seigneur’s estate for one to two days a year. Additionally, habitants were responsible for providing corvée for building any public infrastructure that the community required. From the Nine Years’ War (starting in 1688) to the construction of the Chemin du Roy (1732), colonial officials experimented with mass corvée labour mobilization in Canada. A number of factors allowed habitants to challenge authority when they felt the colonial élite had violated their right to subsistence. When drafted annually into forced labour for the construction of Québec and Montréal’s fortifications, groups of habitants refused to show up for work, called upon their superiors to protect them from service, or collectively discussed mutiny if conditions did not improve. During the first three decades of the 18th century, corvée was a negotiated process, with habitants constantly putting forth their own definitions of acceptable labour mobilization.

Keywords: corvée, labour history, Québec, New France, seigneurial system, habitants, mutiny, protest

Résumé : L’article examine l’évolution de la main-d’œuvre ou la corvée canadienne à la fin du 17e et au début du 18e siècle de l’Empire française. En Nouvelle-France, les locataires, appelés habitants, louent des terres à des seigneurs en échange de plusieurs impôts. La taxe sur le travail, ou la corvée, obligeait les habitants à travailler sur le domaine de leur seigneur un à deux jours par an. De plus, les habitants étaient responsables de fournir la corvée pour la construction de toute infrastructure publique dont la communauté avait besoin. De la guerre de Neuf Ans (à partir de 1688) à la construction du Chemin du Roy (1732), les fonctionnaires coloniaux expérimentèrent la mobilisation massive de la main-d’œuvre ou la corvée au Canada. Un certain nombre de facteurs ont permis aux habitants de contester l’autorité lorsqu’ils estimaient que l’élite coloniale avait violé leur droit à la subsistance. Lorsqu’ils sont enrôlés annuellement dans les travaux forcés pour la construction des fortifications de Québec et de Montréal, des groupes d’habitants refusaient de se présenter au travail, demandaient à leurs supérieurs de les protéger du service, ou discutaient collectivement de mutinerie si les conditions ne s’amélioraient pas. Au cours des trois premières décennies du 18e siècle, la corvée était un processus négocié, les habitants proposant constamment leurs propres définitions d’une mobilisation de la main-d’œuvre acceptable.

Mots-clés : corvée, histoire du travail, Québec, Nouvelle France, système seigneurial, habitants, mutinerie, révolte

On 6 November 1714, Michel Bégon, the intendant of New France, ordered all male tenants of the seigneuries surrounding Montréal to quarry and transport limestone for construction of a wall by corvée. During autumn, these proprietors, referred to as habitants, were “employed to draw the stone from the quarries and to amass it on the fields” while a second corvée of horse teams hauled the materials to the city.1 By August 1717, the habitants of Longueuil, a seigneurie on the opposite side of the St. Lawrence River from Montréal, had yet to fulfill their obligation. As a result, Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, the governor of New France, decided to travel to Longueuil with several soldiers to personally direct the mobilization of labour.2

When Vaudreuil arrived, several habitants armed with muskets greeted him and refused his order of corvée. To subdue the community, Vaudreuil called a meeting of all habitants in the seigneur’s manor, where he told them “to imitate the habitants of the other côtes.” In a letter recalling the events, he described this as “useless because among them were mutineers who spoiled the spirit of others.” Tensions escalated when a group of village folk voluntarily left with the governor’s armed guard. The mutineers, believing that they would soon be imprisoned, “left the house in a crowd and gathered their weapons.” Ten of these mutineers went back to their homes, where they barricaded themselves with their muskets overnight. Vaudreuil, seeing “little submission of this people,” returned to Montréal to decide how to prevent outright revolt. The parish priest, seigneur Longueuil, and four of the principal habitants travelled to Montréal and pleaded leniency for the mutineers. They eventually surrendered themselves and spent two months in the dungeons of Montréal.3

Notwithstanding the relatively peaceful end to this protest, the episode illustrates the dramatic forms of habitant contestation to corvée labour that developed in Canada. This article examines the evolution of corvée labour in 17th- and early 18th-century New France. From the Nine Years’ War (1688) to the construction of the Chemin du Roy (1732), colonial officials experimented with mass corvée labour mobilization in Canada. The brief siege of Québec (1690) exposed the colony’s weak military defences and lack of communication infrastructure. As a result, metropolitan royal ministers and colonial officials embarked on a massive overhaul of the region’s fortifications, roads, and bridges. They agreed that habitants would provide the majority of this labour by corvée.

Ministers in Versailles mobilized Canadian corvée labour for the construction of fortifications and roads as part of a broader royal scheme to extend the authority of the monarchy in the French Empire. In the late 17th century, King Louis xiv ordered the construction of a network of massive fortifications on France’s eastern border as a buffer to protect recently acquired territory and impose his prerogative on his royal subjects. In France, the mobilization of corvée labour relied heavily on the mechanisms of authority embedded in royal statutes and the strength of the seigneurial system.4 Politically influential ministers, economically powerful seigneurs, and tax collectors fulfilled Louis xiv’s orders and coerced the rural population into corvée for these projects by appealing to the peasant’s feudal dues to the Crown.

The construction of fortresses and roads in New France correlated with the king’s overhaul of royal authority on the continent. The onset of the Nine Years’ War and the siege of Québec in 1690 convinced ministers in Versailles that the North American colony was vulnerable to English attack. In the aftermath of the siege, envoys and engineers from Paris arrived fully equipped not only with the plans to refortify the St. Lawrence city, but also the understanding of mobilizing the working population on corvée. Orders of corvée in New France emulated those of Louis xiv. Moreover, ministers and colonial officials expected to call upon the same obligation habitants owed to the Crown as their continental counterparts. Chronically underfunded, their plans for the Québec fortifications relied upon the willingness of habitants to cease their agricultural work, travel from their dwellings to the city, and work for ten- to fifteen-day rotations digging earthwork structures and guiding horse teams to the construction site.

This article builds on a growing body of scholarship concerned with the entangled relationships among labour, law, and empire in the colonial Atlantic. In recent years, research has revealed the diverse nature of colonial labour – the spectrum of “unfreedom” – that underpinned the economies of European empires in North America.5 Scholars of the colonial Atlantic have complicated the binary between slavery and freedom to illuminate the variety of extralegal techniques that empires used to impress colonists into the workforce. In Canada, recent attention to Indigenous enslavement has shed light on France’s efforts to install a racial hierarchy and the challenges that First Nations’ faced as they navigated increasingly restrictive laws that attempted to commodify them to the status of property.6 As a labour system derived from feudal law, Canadian corvée provides a unique study of how the French Empire mobilized their subjects and manipulated these social arrangements for imperial objectives.

Sparse, dispersed settlement, distance from royal reprimand in France, poor communication networks, and a short growing season ultimately opened up new possibilities for Canadian labour negotiations between the royal élite and habitants not available on the continent. Indeed, seigneurial obligations met the harsh realities of life in the New World. During the early 18th century, habitants developed a disdain for corvée and many proprietors evaded the duty whenever possible. When annually drafted into forced labour for the construction of Québec’s and Montréal’s fortifications, habitants refused to show up for work, called upon their superiors to protect them from service, or collectively discussed mutiny if conditions did not improve. During the first three decades of the 18th century, corvée was thus a “negotiated” process, with habitants constantly putting forth their own definitions of acceptable labour mobilization.7

Disdain for corvée was neither random nor arbitrary. Groups of habitants protested corvée when they determined that the French colonial state had overstepped the obligations their concessions stipulated. Officials expected habitants’ obedience based on written metropolitan legal codes and subordination to their superiors. If the élite viewed the early 18th century as a period of experimentation with corvée, groups of habitants interpreted it as a period of experimentation with resisting royal orders. To be sure, resistance to seigneurial dues was not unique for corvée labour. Canadians protested grain prices, tithes, and the stringent alcohol regulations imposed by the Crown.8 Corvée protests highlight the intersection of local and royal grievances. They utilized corvée as a medium to protest unremunerated labour, the intrusion of state intermediaries into their communities, and the customs of a kingdom across the Atlantic.

Many parishes, however, obeyed their orders, and ditch by ditch, road by road, corvée labour constructed the infrastructure of Canada. On the one hand, the orders of corvée acted as a practical means of extending the communication and commercial networks of the seigneuries. On the other hand, the intendant’s orders symbolically reinforced the inherent authority of the king and his representatives in the colony. Orders of corvée and their subsequent execution provided powerful reminders to habitants that their obligations were intertwined with their material existence and were a requirement of their land tenure.

New France, the Seigneurial System, and the Canadian

Colonial State

Canadian labour laws and administration followed the customs of France. By the early 17th century, France exhibited a robust legal tradition based on an amalgamation of royal orders, written seigneurial statutes, and unwritten social arrangements ironed out and refined over several centuries of local negotiations. At the seigneurial level, custom operated to transform a “legal norm recognized by a community of inhabitants” into a practised tradition.9 The king’s orders clarified such local arrangements, standardizing each practice and forming a coherent, kingdom-wide code. The king’s orders dealt “with the content of the custom and at the same time with the recognition of the public authority which validates it.”10 As legal historian Martin Grinberg asserts, at the core of custom was “reciprocal consent, between the king and his representatives, and the people.”11 Custom served to bind peasants, seigneurs, and king together in mutually beneficial arrangements of governance and order.

Although custom maintained the language of “consent” and “reciprocity,” 17th-century France was by no means egalitarian and functioned within a strict, rigid hierarchy of duty, honour, and obedience. Peasants owed seigneurs numerous taxes, such as corvée, and seigneurs owed fealty and tribute to the king. Locally, for peasants, the intersection of hierarchy and custom was felt most on the seigneurie, large estates operated by a lord and worked by inhabitants. Taxes, in the form of labour (corvée), money (cens), and goods (banalités), were an essential characteristic of rural life in France. Customary civil law functioned to mitigate some of the exploitation an inhabitant could experience at the hands of his seigneur and allowed limited opportunities to challenge the élite in court to gain compensation for lost work or crops.12 As E. P. Thompson states, custom maintains the “unwritten beliefs, sociological norms, and usages asserted in practice but never enrolled in any by-law.”13 Inhabitants wielded these customs, to the best of their ability, as protective measures against exploitive seigneurs to ensure that they upheld consent and reciprocity.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, La construction d’un grand chemin, 1774, oil on canvas.

Musée du Louvre, Paris. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

In Canada, custom also dictated the obligations that habitants owed their superiors. Similar to France, the nobility and the religious élite owned seigneuries, large swaths of land extending from the St. Lawrence. The seigneur subdivided this property among colonists. Other than an annual property tax, referred to as a title deed, habitants were subject to a variety of feudal dues. Calculated by the amount of occupied arpents of land, the habitant paid for rent, or cens, through a portion of his harvest or in coin.14 This agreement between tenant and landlord derived from a private arrangement.15 In conjunction with the rent paid directly to the landholder, the tenant also agreed to a grist-mill banalité, obligating habitants to “grind grain at the seigneurial mill.”16

In 1664, King Louis xiv codified these arrangements into a colonial legal system, articulated in the Custom of Paris. As Allan Greer asserts, the “Custom of Paris was formally pronounced the exclusive law of the French Empire.”17 Importantly, the Custom reaffirmed the seigneur’s ability to levy droits extraordinaire, those feudal privileges agreed upon by tenant and landholder in each title deed.18 While comprehensive in compiling the array of local and kingdom-wide edicts of the empire, the Custom did leave significant openings for adaptation. Indeed, Greer highlights that “other tenure conditions and exactions could be added, by contractual agreement, to the baseline conditions legally applicable to all censive holdings.”19 Corvée, for example, was not directly mentioned in the articles. In short, while not explicitly addressing corvée, the Custom ensured that future title deeds that contained the labour system under droits extraordinaire kept tenants tied to that obligation.

As result, early uses of Canadian corvée fell under the responsibility and discretion of the seigneur. Documents from the early and mid-17th century are sparse, but Marcel Trudel has shown that habitants owed up to two days of corvée based on the seigneur’s prerogative.20 Although no strict, uniform legal definition of seigneurial corvée existed in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, custom consisted primarily of agricultural labour performed in accordance to each individual title of concession. As a legal contract of landownership, these concessions also stipulated the feudal dues that habitants owed to their seigneur. As a result, corvée often appears in these documents, stipulating the type of agricultural labour that seigneurs expected habitants to perform as well as the number of days each individual habitant should work on the seigneur’s demesne.21

Seigneurial corvée conformed to the rhythm of crop rotation and the seasons. Last frost, typically in April, signalled a critical working period when habitants planted seeds for the year’s crops. Habitants tended the crops from May until the end of August, and then from when the harvest began in earnest in September until the beginning of November.22 In the summer months, habitants remained busy clearing land in anticipation for the next year’s planting, tending livestock, cutting wood for the winter, expanding the family farm with outbuildings, and observing the progress of the currently planted crops.23

Several documents provide insight into the experiences of habitants on seigneurial corvée. For example, a legal dispute over ownership of the Bouchard Islands, a series of small islands in the St. Lawrence, required the Superior Council’s clarification as to which habitants owed fealty to each seigneur. Michel Bégon, the current intendant, decided that “the habitants must give their lord, seigneur Desjordy, the days of corvée mentioned in their concession titles” but that the seigneur should request the labour “at different times and separately” throughout the year. Furthermore, he asserted that “the seigneurs of this country make their tenants pay to them, while the seigneur makes them give days of corvée for everyone that sustains a possession,” and that the seigneur can oblige “them to give him days on his estate.” Bégon specified that each habitant owed the seigneur “three days, one in planting, one in the harvest,” and one for the construction of buildings on the property, such as a mill. The titles of concession, duty, and obligation compelled habitants to fulfill these three days of labour, and the seigneur, parish priests, and captains of the militia oversaw the distribution of labour.24

Depending on the season or the amount of work that needed execution, the seigneur could request extra days of corvée. This especially occurred during wartime, when the demands of the military placed an extra burden on parishes. The seigneur expected the habitants to fulfill these demands. The intendant specified, however, that “those who will have to give more than the three days labour during war shall be allowed to exempt corvée by giving 40 sols for each [day] provided that they pay cash for those who come to work for them.” These arrangements between habitants were privately organized and the seigneur largely allowed them to pay others for their corvée as long as the work on the property was done. Each seigneur dictated different terms of concession, and the amount of time habitants spent performing corvée in homage varied from seigneurie to seigneurie. In St. Ours, for example, along with the expected agricultural duties, the seigneur required habitants to collect wood on the property.25

Several overlapping units of administration were grafted on top of each individual community. Within the seigneurie, clusters of habitations, or dwellings, formed a parish.26 The parish represented the Catholic Church’s jurisdiction among the Canadian habitants.27 Priests collected tithes and exerted limited, but influential, authority over habitants’ day-to-day lives. Next, for communication purposes, seigneuries that exhibited a similar geography were grouped into côtes. Each côte contained a captain of the militia in charge of dispensing royal orders, collecting taxes, mobilizing corvée, and mustering the militia.28 The various côtes fell under the jurisdiction of one of the “governments” of New France. In the St. Lawrence Valley, these governments consisted of Montréal, Trois-Rivières, and Québec. The governor appointed three lieutenant governors to manage the civil affairs in each of the governments.

Inter-imperial competition and warfare challenged the French Crown’s rule over habitants in his colonies. The Nine Years’ War (1688–97) had a profound impact on colonial policy in New France. With the exception of the Anglo-Dutch War in New Amsterdam, European wars had been primarily waged on the continent, therefore increasing tension in the northern colonies but not directly threatening the posterity of the region. To be sure, borderland disputes challenged European supremacy in southern New France and northern Anglo-America, but the conflicts remained small-scale regional disputes.29 In 1690, however, an English squadron of ships, under the command of Sir William Phips, governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, sailed into St. Lawrence Bay and put the city of Québec under siege. When the current governor of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, refused English terms of surrender, Phips landed 1,500 Massachusetts militiamen north of the city and ordered them to prepare for battle. The French garrison answered with a bombardment directed toward the English ships anchored in the river and a sortie of Canadian militiamen who easily repulsed the Massachusetts militia. After losing two ships, Phips retreated and returned with his force to New England.30

The brief, yet traumatic, siege of Québec exposed the colony’s military vulnerability and convinced Governor Frontenac and his intendant, Jean Bochart de Champigny, that the St. Lawrence Valley required a serious overhaul of the colony’s defensive fortifications. The Crown had nearly lost its most valuable city in the north, access to the St. Lawrence, and the lucrative fur trade as a result. In the aftermath of the siege, envoys and engineers from Paris arrived fully equipped with the plans to refortify the St. Lawrence city.

The Québec and Montréal Fortifications, 1690–1720

The first major construction project entailed strengthening Québec’s fortifications and creating permanent, stone walls surrounding the city. To achieve this, Louis xiv ordered Jacques Levasseur de Neré, a Paris-educated engineer, to travel to New France and assess the defensive fortifications. Upon arrival, Levasseur proposed fortifying the Upper Town with a stone wall, in addition to a number of earthwork redoubts and palisades. He proposed harnessing “the Corvées which the habitants must satisfy” the following spring, in addition to explicit orders to the governor and intendant to “increase them as much as” they could for the fortification of the Upper and Lower Towns.31

In addition to Levasseur and his subengineers, the mobilization of corvée was carried out under the orders of two different governors, Frontenac and Vaudreuil. Their orders then passed on to one of several intendants of New France who served their tenure during the construction period, including Jean Bochart de Champigny, François de Beauharnois, Jacques Raudot, and Michel Bégon. Influential subjects of the government of Québec also stepped into key roles on the construction project, especially Louis de la Porte de Louvigny, a wealthy noble from France and major in the Troupes de la Marine.32 Finally, the project was overseen in Versailles by Jérôme Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain, the secretary of the Marine, who approved and issued all funds related to the construction of the fortifications.33

These ministers and colonial officials assumed they would call upon the same corvée obligation that habitants owed to the Crown as their continental counterparts. Each arrived in New France with the expectation that habitants would perform their duty and work on the site.34 Indeed, historian Anne Conchon emphasizes that in France the peasantry was “required for the construction of military roads between forts or fortifications on the front line.”35 The royal élite in Versailles viewed corvée on fortifications as a natural extension of seigneurial custom and the legal obligations that bound tenants to their noble landholders. Despite the pleas from those in the colony, the secretary of the Marine chronically underfunded the fortifications of Québec. As a result, their plans for the Québec fortifications relied upon the willingness of habitants to work for ten- to fifteen-day rotations on the site to mitigate the lack of surplus cash for full-time wage labourers and craftsmen.

Levasseur expected habitants to contribute to the fortifications as part of their obligation to the Crown. Indeed, he wrote that “it is [the king’s] intention that the habitants should do the works of the land by corvée as they have by custom that right.”36 For Levasseur, habitants – similar to their continental counterparts – legally owed labour to the Crown. In 1706, Louvigny stated that “it is absolutely necessary to make [the habitants] obey” and to “execute the Corvée as they were regulated by the Governor and Intendant.” Although custom dictated obedience to the Crown on behalf of the habitants, the officials overseeing the project also held a responsibility to manage labour appropriately and alleviate abuse. For example, Louvigny continued that Levasseur “saw that the work was going on in length” and did not want to “harm the sowing of the seeds.” As a result, he dismissed the habitants who “are absolutely necessary for the countryside and the harvest.”37 In order not to disrupt the delicate planting and harvest seasons, officials utilized the ancien roolles, or Rolles, drawn up by the seigneur for taxation purposes to institute an annual draft of labour from the parishes located within the jurisdictional boundaries of each individual government.38

For royal authorities, corvée came to represent obedience and consent as much as it did actual labour. In her discussion of imperial sovereignty, Kathleen Wilson asserts that colonial state power was “performative rather than institutional” and “focused on the organization of social life and national affiliation among colonizers and colonized alike.”39 Indeed, Canadian corvée labour came to function as a “regulation of individual and collective behavior that polity depended upon, rendering ‘domestic order’ within and without the state possible.”40 In this sense, every fortification and road constructed by habitants set a precedent – and custom – of utilizing the agrarian population for mandatory work. As James C. Scott argues, “every visible, outward use of power” provides a “symbolic gesture of domination that serves to manifest and reinforce the hierarchal order.”41 The creation of a routine around labour mobilization fostered the production of a Canadian custom of corvée that drew influences from France but integrated the realities of the New World into its legal traditions.

The organization, management, and division of corvée labour depended on the objectives of each fortification project. For the Québec corvée, the division of labour signified what type of tasks each habitant would participate in upon arrival. Based on each seigneurial tax roll, officials subdivided habitants by journées d’hommes (days of manual labour) and journées de harnois (“harness days,” or days of providing horse teams to cart raw materials and supplies to the site).42 In Québec, labour primarily took place on the terraces, but between 1707 and 1715 the work expanded to “retrenching the barricades,” building communication roads between redoubts, and fortifying the “strong entrenchments” that defended the bluff.43 The local parish militia captain gathered these habitants together and, collectively, they travelled to Québec.44

Once habitants serving their corvée had arrived at the city, the engineer assigned them to a specific location where they would fulfill their days. Squads of habitants worked directly on the site, digging trenches, removing earth for redoubts, erecting wooden palisades, or carrying stone to the wall.45 Habitants on corvée also excavated a six-foot-wide moat around the Intendant’s Palace. Engineers, craftsmen, artificers, and stonemasons oversaw the corvée and managed the habitants’ contributions to the project.46 Habitants performing manual labour served ten days if they brought their own food for subsistence and fifteen days if they took rations from the king’s stores.47

The second contingent of corvée, those habitants serving with horse teams, brought carriages for the transportation of supplies and excavated earth. In Québec they were divided into two squads and assigned specific tasks that correlated with the completion of the fortification. Both squads carted “timber which arrived at the harbour” to the construction site. Habitants serving their corvée with horse teams performed this work for five days before officials dismissed them.48

Each October and November, the Québec fortification corvée must have produced an impressive sight for all involved. Several hundred habitants arrived from the surrounding côtes in rotations with carts, dumpers, and horse teams.49 Chilled by the autumn air, the construction site exploded with activity as habitants on journées d’hommes carried stone, timber, and wheelbarrows filled with excavated earth to the walls.50 Militia captains put habitants armed with scythes to work clearing the thick underbrush that obstructed the fortifications’ line of sight.51 The work yard would have resonated with the sounds of hammer on stone breaking boulders into manageable pieces. One would hear the low thump of dozens of shovels striking the ground, clearing the way for redoubts and other earthwork barriers.52 The sound of axe on timber in the distance would have echoed around the city as men felled trees and split the logs into palisade stakes.53 Livestock and domestic animals alike would have added to the chorus of noise. Oxen teams would have pulled tree trunks and stumps from the ground while horses struggled with loads of stone and dirt.54 Habitants driving their horse teams would have hollered at the horses as their carts, overpacked with construction materials, broke down and required repair.55

Below the cliffs of Cap Diamant, a second group of habitants would have been hard at work transporting timber and stone down the St. Lawrence in flat-bottomed canoes.56 Carefully navigating their way to shore, the rowers were kept in order by the steady, rhythmic shouting of their captain. Habitants on the shore would have thrown them rope, looping it through a small hole in the bateaux and yanking the team aground.57 Idle habitants would have loitered in groups, smoking tobacco in pipes and taking sips of brandy, far outside the watchful eye of the seigneurs strolling in the city above. Most probably spoke to one another about the upcoming harvest and winter, while others whispered of mutiny and planned their chance to flee the work site unnoticed.58 Overhead, the fleur-de-lys of the House of Bourbon would have fluttered in the wind next to the blue banner of New France and the blue, white-crossed banner with anchors of the Troupes de la Marine. At night, from the banks of the St. Lawrence, the shoreline would have seemed ablaze with scores of campfires, candles, and torches.

Atop horseback, seigneurs, militia captains, Levasseur and his subengineers, and Vaudreuil would have paraded routinely around the work site. Dressed in the finest French justacorps and woollen breeches, they would have stood out not just because of their higher elevation on horseback but also because of their wealth prominently on display for all habitants to see. Militia captains would be seen making rounds to their squads of labourers, frantically checking their tax rolls to make sure that no habitant had deserted the work camp. Some may have been seen quietly cursing the names of habitants who had escaped to their personal farms out of either subversion or necessity to prepare for the harvest. Levasseur and his team of subengineers would make their rounds yelling up to masons parked high above on the uncompleted walls. Quartermasters would have hollered habitants’ names to hand out their rations. Soldiers of the Troupes de la Marine would have continued their regular schedule, drilling in dark grey-blue uniforms with a fife and drum corps keeping each regiment in step.59

From 1701 to 1715, officials reported to Versailles that habitants “satisfied the corvées” in Québec with “much goodwill” and “without difficulty” by annually providing labour for the construction of the city’s fortifications.60 However, resistance by the colonial élite of the city and a lack of funds from the Crown hampered the project during the early years of the 18th century. An initial call for corvée required all residents of the city, regardless of status, to provide “horse teams and carriages of the city with some dumpers to charter the land and carry out the works.” This call led to an outcry from the religious and civil élite, who claimed exemption from corvée by the “prerogatives that they say to have in France” and because it “violates their rights.”61 Indeed, by 1707, Levasseur reported that all of the “affluent people in Québec City” had petitioned for officer status in the militia, thereby “exempting them from working on the terraces like any other part of the public.” Moreover, the élite used custom to reinforce their status, asserting that “they had the excuse that they are coated with a character that dispenses them” from public corvée.62

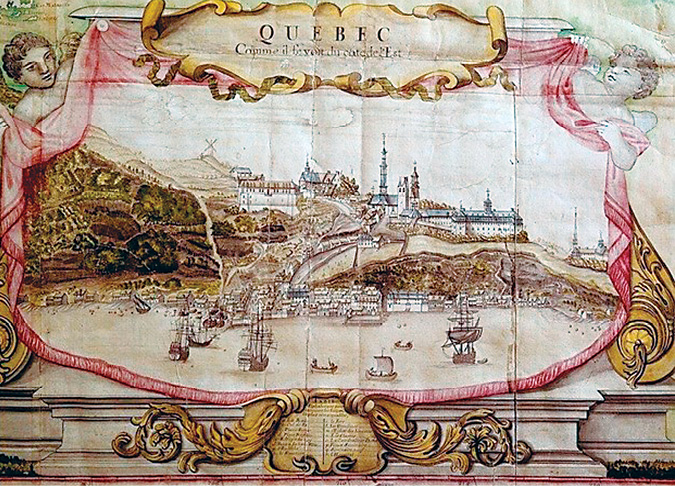

Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, Map of Québec, 1688.

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

The exemptions of the city’s wealthy colonists angered the workers performing corvée. Habitants utilized several techniques to mitigate exploitation. First, communities collectively petitioned the officials, asserting that “it is not Custom in France to utilize them to furnish corvée.” Habitants in particular argued that they were “pulled from their plow” and that corvée disrupted the fragile social bonds of reciprocity that secured subsistence in New France. Petitions such as those received during the Québec corvée represented habitants’ acting in communal defiance of Crown work orders. The habitants claimed they were “vexed to support orders for public works.”63 The petitions not only allowed workers to voice their grievances to the intermediaries of royal authority but also provided them the opportunity to collectively assert their own concepts of proper and legitimate corvée labour. By appealing to their subsistence and to the need to return to their homes to work their fields, habitants successfully forced officials to implement time restraints on corvée.64

Second, in one case, two habitants, named Gabriel Rouleau and Jean Mandras, evaded their militia captain at the initial point of collection and did not show up at the city work site. Once their militia captain realized Rouleau and Mandras were not there, he filed

“a complaint in writing” to Louvigny, who gave him leave to return to the parish and reprimand the men. Once they were caught, the militia captain imprisoned Rouleau and Mandras for 24 hours, making it “known that they would have to come to their duty in a few days.”65

Additionally, in 1707, after the nobility had gained exemptions for corvée, habitants collectively began to “whisper of mutiny.” This, Levasseur explained, derived from “the unfortunate who will be responsible for the weight of this work.” Although little is known about the scope or size of this potential “mutiny,” the existence of discontent prompted Levasseur to write Pontchartrain and suggest that it was important “to prevent what might happen to the people of justice or other people being a militia officer or not contributing to the corvées.”66 Habitants scheming of “mutiny” would become a regular tactic of habitants to voice their discontent about corvée working conditions.67 In particular, habitants found this type of resistance useful in convincing authorities that they would collectively stop working if new conditions, like shorter rotations of manual labour, were not implemented.

During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), the labour of fortification construction also fell on habitants of the government of Montréal. The colonial officials feared the British attacking the southern corridor of New France on Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. To defend this region, in 1709 intendant Jacques Raudot ordered “the habitants of the parishes of the government [of Montréal] to fairly contribute their work” after the harvest, bringing the “stone and wood necessary” for the construction of a small fort on the rapids of the Richelieu River.68 Later known as Fort Chambly, the Richelieu was sparsely populated and required that the captains of the militia “make the distribution between the different côtes” in the Montréal area. Raudot appealed to the threat of conquest, arguing that “the security of the habitants of the government of Montréal request their work.” Habitants worked transporting stone, lime, and timber to the worksite. By 1711, the small stone fort was completed and the officials had turned their attention to fortifying the isle of Montréal.69

Following the war, colonial officials embarked on the third major fortification project of building a stone wall around the city of Montréal. As early as 1714, Claude de Ramezay, governor of Montréal, wrote to Versailles that “he must seriously take advantage of the internal peace to complete fortifying Québec and Montréal” and requested funds to begin planning the enclosure. The initial plan called for a series of strongholds on the river and “walls sixteen feet high.” He proposed “to divide the government by class and oblige each one according to their abilities to work by corvées.” Moreover, he planned to implement a similar division of labour witnessed at the Québec fortifications. Habitants would “draw stone from the quarries,” with an additional subgroup to work onsite at the wall carrying the materials. Similar to the Québec corvée, a second contingent of habitants would provide carriages and dumpers to transport the stone to Montréal. Ramezay considered November the best month to accomplish these goals, for “the command of corvée is hard to do at the beginning of October until the month of April to gather all the materials during the winter.” Additionally, he did not want to disrupt the habitants’ “work from sowing until the cutting of the hay.”70

The governor agreed with Ramezay’s plan and on 20 September 1714 they sent their preliminary report to Versailles for approval. In this document, they asserted that corvée labour provided the most cost-efficient workforce in the absence of funds sent directly from Versailles to hire masons. Indeed, they stated that “as his Majesty does not want to make funds for these fortifications, and it would not be proper to propose a tax,” they judged that “the only means which we can put to use at present is to have them work by corvées obliging all habitants of the government of Montréal.” Habitants would “do their own corvée” to “extract the stone, to do the excavations, and transport on location all materials.” Habitants located too far away from the city would pay in cash “the number of days to which they will be taxed” and thereby be exempt from having to perform hard labour. The revenue collected from this tax, Vaudreuil and Bégon hoped, would “be used for the payment of labour and the purchase of lime.” They assured the minister that “although these corvées are kind of an imposition, the name is not as odious in this country, the people having been accustomed to it for a long time.” To avoid disrupting the agricultural cycles, they set the corvée to begin the following year.71

Bégon authorized the official order of corvée on 6 November 1714. Calling upon the habitants’ obligation to the Crown, he stated that, with “the King wishing to have the city of Montréal surrounded by a wall,” the intendant had decided that “the work should start without delay … and that the habitants of the government of Montréal should contribute.” He continued, “we have judged that the habitants have at the least the responsibility to provide corvée on the openings of the compound.” The captains of the militia were responsible for gathering the labour force and divided “the number of days that each habitant will furnish corvée in proportion to his property and faculties.” In exchange for their days of labour, each habitant could pay three livres per day of manual labour and five livres per day for their requisitioned carriages. Habitants on journées d’hommes would “be employed to draw stone from the quarries and amass it on the fields.” The habitants on journées de harnois would then “work with the pack animals to load the lime necessary” and transport the materials to Montréal. Bégon ended the order asserting that all habitants “without exception” were to “work on the fortifications until the compound of the city is complete.”72 At the work site, a third contingent of habitants worked on the ditches and fences surrounding the stone structure, as well as redoubts that protected the island. The team of engineers in charge of the operation ordered the habitants to “provide all of the materials,” and Ramezay oversaw the organization of work teams putting “the habitants back in the places they had to be in order to make the stone wall.”73

Colonial officials in Montréal encountered staunch habitant resistance to the corvée. The following year, on the scheduled start date of construction, Ramezay and Bégon recalled that the “execution of this project did not seem practicable by the little disposition of the habitants of the government to satisfy” their obligations.74 Habitants failed to show up for their working parties, and rumours of discontent among the parishes trickled into the city. The lack of workers forced construction to temporarily stop until officials could mobilize the surrounding parishes for corvée.75 Habitant opposition prompted Vaudreuil to travel to Montréal in 1717 to oversee the mobilization process and make personal trips to seigneuries that refused to furnish labour.

A poor harvest in 1717 compounded the problems of labour mobilization and prompted one seigneurie, Longueuil, to refuse corvée duty. As mentioned above, when Vaudreuil arrived in Longueuil, he presided over an assembly of habitants “to offer them their Corvées.” During the meeting, the governor’s armed guard left with several of the parishioners. Misinterpreted as an impending punishment by the protestors, this “alarmed the others and all fearing to be charged left the house in a crowd to gather their weapons.” Ten eventually rushed to get their muskets, and the governor, seeing “little submission of this people,” fled back across the river to Montréal. The mutineers barricaded their homes, with Vaudreuil asserting that “they engaged in a sort of revolt by staying with their weapons the rest of the day, except some reasonable people who retired to their home.” Indeed, he further commented that “their intention was to prevent anyone from sending out those whom they foresaw that I might send to take them to prison.”76

Although the ten “mutineers” were eventually imprisoned, this episode not only highlights the fraught social tensions that existed around the obligation of corvée for labour on the fortifications but also illustrates habitants’ demonstration of their own form of communal justice. The outburst, and subsequent punishment, convinced other seigneuries and parishes that they should comply with the order. Vaudreuil stated, “it is true that something bad is good, it has caused several habitants of the other côtes, who have not hastened to satisfy what has been promised for the corvées” to fulfill their obligation.77

Despite the immediate success, Montréal officials remained wary of the social unrest. The poor harvest of 1717 convinced the governor that the corvée should be suspended for 1718. When corvée resumed in 1719, habitants again resisted participating “because they would have to provide themselves with food as a result of the bad harvest of the year of 1717.” Although both Vaudreuil and Bégon continued “the levy imposed on the habitants and the communities of [Montréal] for that expense,” by 1720, Ramezay had introduced a formal monetary tax that Montréal habitants would contribute annually instead of mobilizing corvée. The work during the 1720s continued under the supervision of hired masons and day labourers, with habitants only sporadically providing corvée as part of their obligation to the Crown.78

Corvées Général: Roads and Bridges, 1706–31

Concurrent to the fortification projects taking place in Québec, Chambly, and Montréal, the Crown also experimented with the use of a second form of labour, corvées général, which consisted of mandatory work on public infrastructure.79 Corvées général primarily repaired or constructed buildings, roads, and bridges. Each seigneurie was responsible for raising a corvée for construction of roads that passed through their property. Contemporary authorities did not specify this form of labour as legally distinct from the seigneurial variety. In documents from the 17th century and the first decade of the 18th century, the intendant and seigneurs refer to this work simply as corvée and did not characterize the labour as, legally, a different form of obligation from that of the titles of concession.

Habitants participated in more corvées général, hereafter referred to simply as corvée, than any other form of statute labour during the first two decades of the 18th century. In 1706, Governor Vaudreuil and the Superior Council declared the construction of one continuous highway that connected the major commercial centres of Montréal and Québec. Although this project, later known as the Chemin du Roy, did not formally undergo construction until 1731, the early 18th century witnessed the preliminary stages of this road system and an attempt on behalf of the colonial administration to connect the seigneuries through a unified transportation network. From 1708 to 1729, habitants living on the St. Lawrence constructed interconnected clusters of highways surrounding Montréal and Québec that formed the arteries of the French colonial state authority in Canada.

Under the French, corvée played a specific role in the construction of public infrastructure, most notably roads and fortifications. The colonial state’s dependence on this labour system stemmed partially from the relatively small population of migrants from France and thus a lack of able-bodied workers. As stated, however, the French were not new to mobilizing varying degrees of unfreedom through coercion. For example, within Canada, corvée and its peculiar feudal social arrangements operated alongside both First Nations and African slavery. In mid-17th-century New France, enslaved Indigenous peoples (referred to as panis or esclaves) played an important role not only as a symbolic demonstration of gift-giving in the Pays d’en Haut fur trade but also as labourers in urban settlements. Both Québec and Montréal merchants traded in Native American captives and sold them to wealthy seigneurs.80 Enslaved Native Americans fulfilled critical domestic and agricultural tasks on seigneuries. While they most likely worked side by side with habitants performing seigneurial corvée, their status as esclaves prevented them from obtaining a title deed and thus exempted them from feudal dues such as road construction.81

Similarly, corvée also made up for a large working shortage from engagés, day labourers, and skilled craftsmen needed for public infrastructure. Engagés, or indentured servants, played a crucial role in agricultural labour, but their contracts denied them from land tenure until their service to the seigneur was complete.82 While many habitants employed engagés, it is not clear whether servants were sent to fulfill their masters’ days of service building public infrastructure. Indeed, corvée tax rolls simply mark the name of the habitant and days owed, without distinction of how many engagés they may have employed.83 In sum, corvée filled an important role in the spectrum of inequality that developed in early 18th-century New France.

During the early 18th century, habitants worked most often on grand chemins, or “highways.” These roads consisted of an enclosed 18-to-24-foot-wide road that passed through the seigneurie or parish.84 Highways served as the primary commercial routes of traders, merchants, and fur traders travelling between Montréal and Québec. The proposal for the roads derived from the intendant, who then appointed Pierre Robineau Bécancour as grand voyer (the surveyor and inspector of roads) to oversee the execution of the orders. Within the hierarchy of New France, the grand voyer emerged as a critical intermediary of the intendant. Bécancour oversaw the implementation of orders related to road and bridge construction. He determined the location, path, and dimensions of each road. For each construction project in the colony, Bécancour contacted the local seigneur, militia captains, priests, and churchwardens for approval. Indeed, on 18 May 1710 in the seigneurie of Ste.-Anne, for example, Bécancour asserted that based on the “consent of the lord proprietor and the lieutenant of the militia of the seigneurie and six of the oldest and most considerable habitants, the churchwardens have settled the highway.” In such orders, the grand voyer typically specified that the habitants would perform this labour under obligation of corvée, making participation in the process a mandatory community obligation.85

The parish militia captains organized labour based on the arrangement of the community. After the parish mass, the militia captain would read the king’s order of corvée and habitants had eight to ten days to contribute their share of labour to the construction project.86 Each captain oversaw the construction of their highway in segments, with habitants “required to make the roads that pass through their land.”87 Based on the route of the road, the intendant sometimes called upon habitants to contribute more than just the length of road that passed through their land. For example, on 24 June 1713, Bégon ordered that the habitants of St.-François and St. Johns “will be led to the places marked by the plan … and build through the places in the forest.” In this case, the clearing of trees required that “each habitant by the road or the land do all necessary work to make [the road] practicable along his habitation.”88

The intendant and grand voyer correlated road construction to the rhythms of habitant agricultural production. Corvée labour on roads occurred “after the planting,” usually around April, and lasted until the end of August, when they expected to begin the harvest.89 By early December, however, habitants were expected to “mark winter roads.” Officially enforced in 1709, the marking of winter roads obligated habitants to drive stakes into the stretch of highway that passed through their land. Originally, Raudot asserted that, it “being necessary to make a road in this season between the city of Montréal [and Québec],” all habitants of the colony should “mark in front of their dwelling a road in the places most convenient.” This order, posted on the parish door, specified that the winter road maintained “the business which happens every day and which establishes a necessary relationship between the two cities.”90 In 1713, Bégon continued his predecessor’s orders and issued an order stating that “the roads being unpassable this season because of the great amount of snow that is all over the land and [St. Lawrence] river the voyageurs are at risk of getting lost if the roads are not clear.” This colony-wide order specified that habitants “whose dwellings are located on the highway place markers each according to the extent of their dwelling so that the voyageurs do not run the risk of falling.91

The maintenance of winter roads was instrumental for the highway system of New France. Cornelius Krieghoff, Run Off the Road in a Blizzard, n.d. [19th century], oil on canvas.

Joyner Waddington’s Auction House, Toronto. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Habitants could contest the construction of a larger highway and submit a plea to the grand voyer to decrease the size of the project. In d’Argentay, for example, the habitants met with the grand voyer to discuss the construction of a highway through their parish. The grand voyer noted that “between them they believe that the road would be most useful and necessary for them to the mill of the seigneurie.” The habitants “argued that the [new] road up and down the older highway will continue and that there will be made a road” that connects to the mill. In this case, the habitants successfully petitioned the grand voyer for a smaller, local road that was more useful to them than a new highway.92

Along with major construction projects, the colonial administration also expected habitants to perform corvée for the associated auxiliary tasks. This primarily took the form of lining each road with a fence and ditches to ensure that the roads would not flood or deteriorate from grazing livestock wandering the parish. In most instances, the orders for fences and ditches accompanied the orders for roads and the intendant held communities accountable for making “the fences and ditches in accordance with the Regulations according to the Grand Voyer.” Another task associated with construction required habitants to clear lands “covered with brambles and shrubbery.” In 1714, habitants of the seigneurie of La Chesnaye cleared the land of this vegetation “on the edge of the river La Chesnaye in front of their dwellings in order to make the navigation of the river less dangerous for those who go to the mill” on the seigneurie.93

Other than highways, habitants also constructed bridges as part of corvée duty. In order to connect the parishes along the St. Lawrence, the intendant ordered the construction of bridges approximately six feet wide “and solid enough to suffer the weight of horses crossing.”94 The grand voyer mobilized this corvée labour in a similar manner as the roads. The militia captain read orders for corvée at Sunday Mass and the intendant designated a schedule in which they should construct the bridge. Unlike the roads, the construction and maintenance of bridges fell to the entire community and the amount of labour they contributed was not limited to the location of their dwelling. Indeed, in the parish of St.-Joseph, the intendant ordered “that the three bridges be maintained in common by the habitants of the parish.”95 Although the size of the bridges depended on each parish’s geography, an order from 25 November 1721 specified “that all the habitants of the Petite-Rivières” were ordered “to incessantly each make, in right, twelve piles of cedar and spruce, thirteen feet long, to serve to re-establish the bridges and roads along the côte as soon as the planting of next year is finished.”96

The amount of labour required to collect and transport wood for bridge construction had the potential to disrupt the resources of the community. A number of disputes within the colony over where in the parish the necessary timber would come from forced Bégon to standardize the system of collection. He asserted that “the disputes that have arisen over the furnishing of wood needed to build the necessary bridges on the rivers that pass the highways” required that “all wood needed for the construction of the bridges will be taken only from the land nearest the river.” In addition, Bégon ordered that the captains of the militia should oversee the distribution of corvée to make sure habitants did not delay in the work necessary for these projects.97

Larger seigneuries with two rows of settlement, one on the St. Lawrence and one farther inland, posed problems in mobilizing labour for the colonial administration. The intendant typically ordered habitants to build roads that stretched through their property, and these almost always correlated with the main highway that ran along the river. As a result, in larger communities with multiple ranks of settlement, the intendant specified the various duties associated with the construction of bridges and roads. In these ordinances, Bégon exerted influence in organizing and distributing labour. In Durantaye, he ordered “the habitants of the second row of the seigneurie of Durantaye whether resident or non-resident, to make their concessions, and make and maintain the new road of the second row which is to descend to the river.” Meanwhile, he ordered the first row of habitants “to help and contribute” the “necessary bridge to make the [new] road practicable.” Depending on the amount of time it took to build the new road, the second-row habitants would aid in the bridge once they finished.98

Habitants exerted considerable influence in the construction of bridges. Following the establishment of parishes as the central focal point of administration, the intendant increasingly relied on an “assembly of habitants” to determine the specifications of the projects based on their local needs. These meetings occurred after Sunday Mass with the seigneur, priest, wardens, and militia captains in attendance to monitor the discussion. Two primary forms of these meetings emerge from the documents. First, the intendant would specify in his order that the habitants should elect from among the assembly four to six “principle habitants” who would then meet with the élite and make decisions of corvée based on what they deemed appropriate.99 The second form of assembly generated a truly representative institution in which the habitants deliberated among themselves. Once a “plurality of votes” rendered a decision, they appealed directly to the intendant’s office.100

Seigneurial custom did not necessarily dictate these meetings, and certain parishes utilized this form of representation to mitigate the abuses of corvée. The most detailed example comes from the parish of St.-Laurent. By April 1722, the bridge in St.-Laurent had fallen into disrepair and needed to be replaced immediately. The bridge served as a central artery of the seigneury and was on the “main road that leads to the mill on which carts cannot pass over it.” Bégon asserted that “it is right to restore the bridge and for greater convenience of the habitants” to move the location of a new bridge to “higher up the river where it is wide which would be less important for construction and maintenance.”101 Ultimately, however, he left this decision – to reconstruct the bridge in the same location or to move it up the river – to an assembly of the St. Laurent habitants. Bégon received his answer just three days later, noting that “all the habitants of the parish of St.-Laurent having assembled the day after the parish mass have unanimously agreed that it is more convenient for the bridge to reside in the same linkage point” as the old one. He added that the habitants, having collectively made this decision, should furnish the wood and the days necessary for its construction.102

Initially, in the first decade of the 18th century, the intendant authorized construction projects exclusively on a local scale. Bégon designated which individual parish would participate in corvée and the local seigneur or captain of the militia would distribute the labour as they deemed fit. By the late 1710s, however, as clusters of roads and bridges emerged from the patchwork of small fiefs dotted along the St. Lawrence, he began experimenting with mobilizing corvée in two or more parishes in joint ventures. Indeed, in some cases, an assembly of habitants between both communities met and discussed projects among themselves. The mobilization of combined parishes, however, represented a clear departure from the early years of the century. In an effort to expand the influence of colonial state authority, Bégon implemented a recognizable, but transformed, process of labour mobilization in which groups of habitants contributed corvée for projects that did not necessarily correlate with their individual concession title. In sum, the Office of the Intendant generated a precedent of mobilizing labour across parish lines.103

In some parishes, groups of habitants evaded any form of corvée mobilization. Repeat orders from Bégon and Depuy to specific parishes imply that some of the proprietors collectively ignored orders for roads and bridges. In the parish of Charlesbourg, for example, the Office of the Intendant issued seven separate orders addressing the construction of a highway that habitants never worked on or maintained.104 Groups of habitants and individuals also ignored orders of corvée. At first, from 1708 to 1715, the intendant simply reissued the order and called upon the necessary intermediaries to compel habitants to complete construction. In 1713, to discourage disobedience, Bégon began issuing a fine of 3 to 10 livres to the “refusers,” those habitants who simply did not fulfill their individual portion of corvée.105 This system of penalties expanded in scope over the next decade and transformed into an entire section of each ordinance. Not only did fines reach up to 50 livres, but the intendant also utilized seigneurial law to compel habitants into service.106 This took the form of writing the names of the “refusers” into the tax roll, a document consisting of each habitant’s name and the amount of labour he provided during the year. Seigneurs also presented their tax rolls annually to the governor in the foy et homage (ceremony of faith and homage), which reaffirmed fealty between seigneurs and the Crown. In order to instill obedience in the parishes, the intendant called upon habitants’ obligation to colony and Crown. In this sense, their refusal to perform corvée represented much more than insubordination. Instead, by placing their names in the tax roll, the intendant ensured that the Crown identified the refusers and, if necessary, intervene and place further sanctions on titles of concession of the habitants.

For the “refusers,” also labelled “offenders,” the penalties for not performing corvée carried social, legal, and financial consequences. Not only did the captain of the militia label the habitant an “offender” in the tax roll, but the fines levied against these habitants had the potential to disrupt their life through mandated court appearances. In some cases, such as in 1720 in the parish of Contrecoeur, the churchwardens inspected the tax roll and personally contacted the offenders to pay their fines for not contributing to a ditch and bridge in the community. In the case of Contrecoeur, a refusal to work equated to a negligence of public service, punishable by the elected churchwardens of the parish.107

Habitants who continued to refuse corvée faced further penalties. In 1714, Paul Charles Dazé, militia captain of Isle Jesus, appeared before the court of the Royal Jurisdiction of Montréal and submitted a formal complaint that three habitants in his parish had refused corvée on a highway and bridge. The court declared that Jacques Foget, Joseph Éthier, and Michel Charbonneau “will be sentenced twenty livres applicable to the parish of said place,” for refusing a work order issued on 5 July 1713. The crime, the court issued, was that the habitants “refused to work on said bridge”; it ruled that if the habitants continued to refuse their corvée, they would be obliged to pay the fine of 20 livres.108

Conclusion: The Habitant “Spirit of Mutiny”

Despite the fines, court appearances, and disgruntled militia captains, many habitants still refused to perform corvée. In the late 1720s, the fortifications of Montréal and the Chemin du Roy remained unfinished. Statute labour had nearly caused a revolt in Longueuil and even the tax that replaced corvée proved difficult to collect. Although the grand voyer issued hundreds of orders to the parishes of the St. Lawrence Valley, the continuous highway stretching from Montréal to Québec was not even close to completion. After many fines and court-mandated corvée, clusters of roads existed only around the two metropolitan centres.

The French colonial state also lacked the mechanisms of authority that promoted efficient, streamlined work orders. Cloaked in custom and nobility, colonial officers poorly translated the orders from Versailles. Overlapping jurisdictions of the governor, intendant, grand voyer, and local seigneurs produced a diffuse power that lacked the royal credibility of the continent. For some seigneuries, orders of corvée, especially during wartime, must have appeared chaotic. For example, habitants in the seigneurie of Charlesbourg received annual orders from the Crown for fortification construction in the city of Québec, annual orders by their seigneur to work on his demesne, periodic orders from the parish to construct and maintain the presbytery, and, from 1709 to 1729, seventeen work orders from the intendant regarding roads and bridges. The chaotic nature would have only been amplified by the grand voyer, militia captains, seigneur, churchwardens, and intendant issuing each individual order.

Clearly, some habitants collectively refused labour. Despite being labelled “refusers” and “offenders” in the tax roll, many parish members and tenants did not fulfill their orders to build roads. The grand voyer’s personal minutes attest to this, with orders in 1731 citing original statues from 1710 still left uncompleted. While the demands of manual labour undoubtedly led some habitants not to fulfill these orders, Governor Vaudreuil offered his own thoughts on the matter. Writing to Versailles on the subject in 1725, Vaudreuil asserted that there “will always be time to punish those who lack respect and submission to the order of his Majesty.” He continued, “I cannot help on this occasion to inform you that it is not alone the habitants of [Québec] that we notice a spirit of mutiny and independence, but that it has already been introduced to all habitants of the countryside who are at their ease, and whose convenient and idle life to which they are accustomed to for a few years has made them less submissive, less ready to execute orders that they receive in the service of his Majesty.”109

While this scathing assessment may contain elements of truth, Vaudreuil encountered a much more systemic challenge than “idle” habitants “who are at ease.”110 As colonial officials issued their orders on the customs of France, Canadian habitants navigated these regulations and at times collectively evaded corvée. If the conditions of work did not suit their interests, they protested by refusing to work, escaping the site, “whispering of mutiny,” or revolting against royal authority.111 In 1732, the new grand voyer, Jean-Eustace Lanoullier Boiscler, took matters in his own hands, travelling to each parish in the colony and personally overseeing road construction. Under order of the Crown, he established his own tribunal, making punishments easier to enact and fines easier to collect.

Ultimately, however, war forced habitants to fulfill their duty. The War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War brought the struggle for New France to habitants’ doorsteps. During the last decades of New France, corvée transformed from an easily evaded bothersome tax to labour that meant the defence and survival of the colony. More importantly, the uneasy relationships forged through evasion, punishment, and law provided a foundation for a corvée labour regime in the New World. Despite the inability of the élite to mobilize habitants for work projects, the French colonial administration had established a precedent for utilizing corvée. These relationships became woven into the fabric of habitant life, and following the Seven Years’ War the British would integrate the civil custom of labour into their conquered North American province.

1. All translations are my own. Michel Bégon, “Ordonnance pour les courvées des fortifications de Montréal,” 6 November 1714, Fond Intendant, c-13588, 438–440, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa (hereafter lac). A comprehensive definition of the term “habitant” can be found in Allan Greer, Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires, and Land in Early Modern America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 172.

2. Vaudreuil to the Council of the Marine, 17 October 1717, Québec, Archives des Colonies (hereafter ac), c11a, vol. 38, 121–124v, lac.

3. Vaudreuil to the Council of the Marine.

4. For a recent analysis of corvée in 18th-century France, see Anne Conchon, La corvée des grands Chemins au xviiie siècle: Economie d’une institution (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016). On the transportation of metropolitan policies of corvée in New France, see Yvon Deloges, “La corvée militaire a Québec au xviiie siècle,” Social History 15, 30 (1982): 333–356; Kenneth J. Banks, Chasing Empire across the Sea: Communications and the State in the French Atlantic, 1713–1763 (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002); Louise Dechêne, Le Peuple, l’État et la Guerre au Canada sous le Régime français (Montréal: Boréal, 2008).

5. Jared Ross Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2018); Peter Linebaugh & Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Boston: Beacon, 2000); Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage Labour, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

6. Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Rushforth, “‘A Little Flesh We Offer You’: The Origins of Indian Slavery in New France,” William and Mary Quarterly 60, 4 (October 2003): 778–808; Ann Little, The Many Captives of Esther Wheelwright (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).

7. On “negotiated empires,” see Christine Daniels & Michael V. Kennedy, eds., Negotiated Empires: Centers and Peripheries in the Americas, 1500–1820 (New York: Routledge, 2002); Kathleen Wilson, “Rethinking the Colonial State: Gender, Family, and Governmentality in Eighteenth Century British Frontiers,” American Historical Review 116, 5 (December 2011): 1294–1322. See also William Roseberry, “Hegemony and the Language of Contention,” in Gilbert M. Joseph & Daniel Nugent, eds., Everyday Forms of State Formation: Revolution and the Negotiation of Rule in Modern Mexico (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 355–366.

8. Leslie Choquette, “Center and Periphery in French North America,” in Daniels & Kennedy, eds., Negotiated Empires, 200–201.

9. Martine Grinberg, Écrire les coutumes: Les droits seigneuriaux en France (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2006), 71. Sylvie Perrier also addresses the creation of “peasant legal cultures” through French civil law. Perrier, Des enfances protégées: La tutelle des mineurs en France, 17e–18e siècles (Saint Denis: Universitaires de Vincennes, 1998).

10. Grinberg, Écrire les coutumes, 72.

11. Grinberg, 72.

12. Fabrice Mauclair, La justice au village: Justice seigneuriale et société rurale dans le duché-pairie de la Vallière, 1667–1790 (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2008), 138.

13. E. P. Thompson, “Custom Law and Common Right,” in Customs in Common (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 100.

14. Marcel Trudel, Les débuts du régime seigneurial au Canada (Montréal: Corporation des Éditions Fides, 1974), 175.

15. Allan Greer, Peasant, Lord, and Merchant: Rural Society in Three Québec Parishes, 1740–1840 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985), 122–123.

16. Greer, Property and Dispossession, 172.

17. Greer, Property and Dispossession, 189.

18. “Titre ii, Droits Extraordinaire,” in An Abstract of Those Parts of the Custom of the Viscounty and Provostship of Paris, which were received and practiced in the Province of Quebec, in the Time of the French Government (London: Charles Eyre & William Strahan, 1772), 30. The section focusing on the cens appears in “Titre iii, Des Censives es Droite Seigneuruaux,” 34.

19. Greer, Property and Dispossession, 171.

20. Trudel, Les débuts du régime seigneurial, 197.

21. Numerous titles of concession from the late 17th and early 18th centuries are held at Library and Archives Canada and the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec. In Ontario and Québec archives, these documents are archived in “seigneurial collections.” The primary collection that I consulted is Fonds de la Familie Ramezay, Seigneurie Sorel, Titles of Concession, mg18-H54, lac.

22. The seasonal characteristics of corvée referenced in this paragraph derive from an evaluation of 116 separate orders. These represent every order of corvée issued by the Intendant’s Office from 1708 to 1729.

23. Louise Dechêne, Habitants et Marchands de Montréal au xviie siècle (Montréal: Boréal, 1988), 153–155.

24. Michel Bégon, “Ordonnance entre Michel Laliberté et autres habitants des Isles Bouchard et le Seigneur Desjordy,” 13 June 1714, c-13588, Fonds Intendant, lac.

25. “Liste d’habitants qui ont fait du sucre et qui on bûché du bois,” Seigneurie de Sorel, Fonds de la familie de Ramezay, 1381–1382, lac.

26. Dechêne, Habitants et Marchands, 144.

27. Alan Gowas, Church Architecture in New France (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1955), 69.

28. Dechêne, Habitants et Marchands, 144, 201.

29. Owen Stamwood, The Empire Reformed: English America in the Age of the Glorious Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

30. André Charbonneau, Yvon Desloges & Marc Lafrance, Québec, the Fortified City: From the 17th Century to the 19th Century (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1982), 32.

31. Levasseur to the Minister, 10 October 1701, ac, c11a, vol. 19, 254–255, lac.

32. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706, Québec, ac, c11a, vol. 25, lac.

33. Levasseur to the Minister, 10 October 1701.

34. Levasseur to the Minister, 18 October 1705, Québec, ac, c11a, vol. 22, lac.

35. Conchon, La corvée des grands Chemins, 41.

36. Levasseur to the Minister, 18 October 1705.

37. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

38. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

39. Wilson, “Rethinking the Colonial State,” 1295. See also Sudipta Sen, “Uncertain Dominance: The Colonial State and Its Contradictions,” Nepantla: Views from the South 3, 2 (2002): 392–406.

40. Wilson, “Rethinking the Colonial State,” 1300.

41. James C. Scott, Domination and Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 45.

42. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

43. Louvigny to the Minister, 6 November 1707, Québec, ac, c11a, vol. 27, lac.

44. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

45. On the carting of materials and construction of palisades, see Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706. On digging trenches, see Louvigny to the Minister, 6 November 1707.

46. Ramezay & Bégon to the Minister, Montréal, 7 November 1715, ac, c11a, vol. 35, lac.

47. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

48. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

49. The number of habitants that participated in corvée is based on a compilation of tax lists that list the days worked by each individual habitant for the Montréal fortification project. The Québec corvée was larger than that of Montréal and, we can assume, would have required a similar number of workers. See Ramezay, “Rolles de l’Îsle de Montréal,” “Rolles de Varennes, Saint-Michel et Saint Theresa,” “Rolles de Rivières-des-Prairies,” “Rolles de Lachine,” “Rolles de Boucherville,” “Rolles de Vercheres et Isle d’Bouchard,” “Rolles de Isle d’Jesus,” and “Rolles de Lachenaie,” all 6 October 1715, vol. 35, c11a, lac.

50. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

51. Clearing underbrush was a common task of corvée labour for road construction; see Bégon, “Ordonnance des principaux habitants du la paroisse de l’Ancienne Lorette concernant les chemins,” 24 June 1713, Fonds Intendant, c-13588, 207–209, lac.

52. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

53. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706. Corvée woodcutting derives from Bégon, “Ordonnance concernant les ponts et chemins de la petitie rivière,” 25 November 1721, Fonds Intendant, c-13588, vol. 5, 445–446, lac.

54. Information on the noise created by oxen derives from British sources observing corvée. Captain Money, “Captain Money called in and examined by General Burgoyne,” in A State of the Expedition from Canada as Laid before the House of Common, by Lieutenant General Burgoyne and Verified by Evidence (London: printed for J. Almon, 1780), 56.

55. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

56. On the location of the bateaux, see Louvigny to the Minister, 6 November 1707. On the amount of men within a bateaux, see “General Orders,” in James Murray Hadden, Journal of Captain James Murray Hadden (1777), Thompson Pell Research Center, Fort Ticonderoga, Ticonderoga, New York (tprc). On the supplies Burgoyne ordered to be stored in the bateaux, see “Sunday, River Sable Lake Champlain, Brigade Orders,” “Tuesday, Camp at River Sable, June 10, 1777 Brigade Orders and After Brigade Orders,” and “Tuesday, Camp at River Bouquet, June 17, 1777, Brigade Orders,” all in Orderly Book of the 47th Regiment Grenadier Company Major Acland’s Battalion (1777), tprc.

57. Hadden, Journal of Captain James Murray Hadden.

58. Levasseur to the Minister, 12 November 1707, Québec, ac, c11a, vol. 27, lac.

59. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706; Levasseur to the Minister, 12 November 1707.

60. Ramezay & Bégon to the Minister, Montréal, 7 November 1715.

61. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

62. Levasseur to the Minister, 12 November 1707.

63. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

64. Time restrictions on corvée were eventually implemented in 1708, following an investigation into the use of corvée in New France; see Jacques Raudot, “Mémorie de Raudot” (1708), ac, series C11G, Correspondence général, F-421, 66–69v, lac.

65. Louvigny to the Minister, 21 October 1706.

66. Levasseur to the Minister, 12 November 1707.

67. Habitants “whispered of mutiny” several times in the first three decades of the 18th century. It appears once in documents related to the Quebec City corvée and twice in documents discussing the Montréal fortifications. On Québec, see Levasseur to the Minister, 12 November 1707. On Montréal and mutiny, see Vaudreuil & Bégon, “Projet du memoire de Roi,” 23 May 1719, ac, c11a, vol. 40, 301–305, lac; Vaudreuil to the Minister, 18 May 1725, ac, c11a, vol. 47, 149–154, lac.

68. Raudot, “Ordonnance qui oblige les habitants du gouvernement de Montréal pour la bâtisse en pierre du fort de Chambly,” 16 November 1709, Fonds Intendant, c-13587, vol. 3, 196–198, lac.

69. Minister to Beaucourt, 7 July 1711, ac, Série B, vol. 216, 164; Vaudreuil to Raudot, 7 November 1711, ac, c11a, vol. 32, 195–204, lac.

70. Ramezay to the Minister, 17 September 1714, ac, c11a, vol. 34, 354–361, lac.

71. Vaudreuil & Bégon, 20 September 1714, ac, c11a, vol. 34, 228–261v, lac.

72. Bégon, “Ordonnance pour faire les ouvrages de enceinte de la ville de Montréal par corvées,” ac, c11a, vol. 34, 328–329v, lac.