Labour / Le Travail

Issue 89 (2022)

Article

“If You Want Anything, You Have to Fight for It”: Prisoner Strikes at Kingston Penitentiary, 1932–1935

Abstract: For four days in October 1932, during the height of the Great Depression, prisoners at Kingston Penitentiary revolted. They took control of their workshops and brought the convict labour regime to a halt, until the guards and militia violently regained control. This revolt was the culmination of more than a year of organizing and collective actions. Prisoners wrote manifestos, participated in work refusals, elected representatives, and developed a sophisticated critique of the conditions of their incarceration and the penitentiary administration. Using a unique collection of archival documents, this article closely examines the complaints, criticisms, fears, hopes, and frustrations of the incarcerated, whose demands and goals are crucial for understanding how and why the prisoner revolt unfolded as it did. I argue that the prisoners at Kingston Penitentiary, by striking and organizing to assert their dignity, democratically organized their lives and ensured a “fair deal” should be considered part of the Depression-era protests of the unemployed, imprisoned, and marginalized.

Keywords: Kingston Penitentiary, prison strike, prison riot, prison labour, penal reform, penal system, prison narratives

Résumé : Pendant quatre jours en octobre 1932, au plus fort de la Grande Dépression, les prisonniers du Pénitencier de Kingston se sont révoltés. Ils ont pris le contrôle de leurs ateliers et ont mis un terme au régime du travail des condamnés, jusqu’à ce que les gardes et les miliciens reprennent violemment le contrôle. Cette révolte a été l’aboutissement de plus d’un an d’organisation et d’actions collectives. Les détenus ont rédigé des manifestes, participé à des refus de travail, élu des représentants et élaboré une critique sophistiquée des conditions de leur incarcération et de l’administration pénitentiaire. À partir d’un ensemble unique de documents d’archives, cet article examine de près les plaints, les critiques, les peurs, les espoirs et les frustrations des incarcérés, dont les revendications et les objectifs sont essentiels pour comprendre comment et pourquoi la révolte des prisonniers s’est déroulée comme elle était. Je soutiens que les prisonniers du Pénitencier de Kingston, en faisant la grève et en s’organisant pour affirmer leur dignité, ayant organisé démocratiquement leur vie et assuré un « accord équitable » devraient être considérés comme faisant partie des manifestations des chômeurs, emprisonnés et marginalisés de l’époque de la Dépression.

Mots clefs : Pénitencier de Kingston, grève en prison, révolte de prisonniers, travail en prison, réforme pénale, système pénal, récits de prison

To mark the first anniversary of the 1932 riot at Kingston Penitentiary, prisoners clandestinely circulated a program throughout the institution. Its anonymous authors called for a “three minute silent period” beginning at 3 p.m. on 17 October 1933, in “commemoration for the martyrs who sacrificed their liberty that you and I might be freer,” followed by “a general disturbance against [Deputy Warden] Sullivan’s dictatorship” and a “song of liberty.” The program called for “a general discussion” about the dangers of a reactionary backlash by prison staff, expressed frustration that demands for access to uncensored newspapers and radio had not been granted, and celebrated the privileges “that we forced them to give” in the previous year: prisoner-organized bands and sports, smoke breaks during work hours, short periods of freedom to talk and associate with other men, limits to the warden’s power to order corporal punishment, and the end of humiliating practices like shaved heads. Prisoners caught with the program, several of whom had participated in protests the year before, claimed it had been written by members of the prisoner committee. No disturbance or moment of silence occurred that day. The warden, William B. Megloughlin, ordered exemplary punishments in solitary confinement of the 22 individuals found with copies of the program and the deployment of armed guards. He felt that he had “over-awed” the prisoners, although his officers reported more noise than usual in the cell block that evening.1

The victories these unknown writers chose to emphasize, a year after the struggles of October 1932, are particularly revealing of the political thought, priorities, and concerns of prisoners confined at Kingston Penitentiary in the early Great Depression. The 1933 memorial program was not an unusual document of prisoner struggle but a continuation of earlier organizing to challenge abuses and circulate criticisms of prison practices. These earlier efforts had culminated in a strike on 17 October 1932, followed by a series of riots lasting until 20 October 1932 as prisoners resisted the violent resumption of control by guards. The prisoner strikers brought about a profound “crisis of imprisonment” in Canada, throwing into doubt the organization, purpose, and legitimacy of the federal penitentiary system.2 The 1932 riot is a dramatic example that “struggle is the motor of penal change,” yet prisoners’ own suggestions for change were elusive to their contemporaries, diverged from reforms proposed by non-prisoners, and have not been thoroughly studied.3 This article therefore directs its attention away from penal reformers and administrators and toward prisoners and their diverse efforts to influence everyday life at Kingston Penitentiary in the early 1930s.

This article will first look at how prisoners experienced their incarceration and how the material, cultural, disciplinary, and labour conditions structured the meaning of their protest. Following this, I will place the strike and riots of October 1932 in a broader continuum of struggle, by examining how prisoners articulated their grievances and organized resistance leading up to the riot and how they struggled to enforce their demands and claim as their own the new rules and new routines instituted thereafter. Prisoners objected to the arbitrary management of the prison, the harms of imprisonment, and the conduct of custodial staff, while their collective aims – an official role in guiding policy, a fair deal, equality in treatment – mobilized and sustained protest. The arguments and tactics of prisoners paralleled other contemporary struggles, reflecting the influence of incarcerated members of the Communist Party of Canada and the crisis of the Great Depression. The organizing and struggle of prisoners to implement their vision of incarceration at Kingston Penitentiary adds a new dimension to Canadian penal history as well as fresh insight into struggles of the marginalized during the 1930s.

Riots by prisoners are one of the most dramatic and spectacular forms of prisoner collective action, frequently resulting in property destruction, injury, and loss of life, and draw considerable attention and scrutiny from politicians, judges, the press, and many other groups outside the prison. The causes of prison riots are complex and sometimes difficult to discern. Violence and rioting are generally, to outsiders, the most legible expression of often obscure struggles for power and influence inside the prison between inmates, guard staff, and administrators. These struggles intersect with broader social, political, and economic conflicts, whether in the form of the criminalization of certain groups or behaviours, punitive change to sentencing and release, the warehousing of surplus populations during capitalist crises, and the success or prominence of civil rights movements and radical resistance, as the literature on the prisoner rebellions of the late 1960s and 1970s demonstrates.4 Criminologists have characterized 1920s and 1930s prisoner rioting, however, as making simple “housekeeping” demands or protesting against conditions, with prisoners playing little role in penal change.5 This characterization, as Alyson Brown has argued, understates the complexity and coherency of prisoner grievances and values.6

Riots by prisoners are part of a “continuum of practices and relationships” of prisoner resistance, as inmates, whether collectively or individually, have used numerous tactics to control their bodies and make their lives more bearable.7 Besides the risky collective action of riots, work stoppages, and strikes, this includes events like escapes, arson, self-harm, and routine but minor hindrances to institutional hegemony: denigrating staff through feigned ignorance, theft, shirking, foot dragging, gestures of contempt, and mockery. These forms of resistance are so common as to be considered an intrinsic aspect of incarceration. The antagonism of the incarcerated is generally understood not as mindless opposition but as the expression of individual and collective identities and goals.8

As Lisa Guenther writes, “people do not wake up one morning with a perception of the intolerable and a desire to fight against it.” Prisoner resistance, especially in the form of collective action, is not inevitable, nor are all forms of non-compliance with prison regulations acts of dissent. Prisoners accommodate and accept prison order, whether out of agreement with the regulations, fear, self-interest or personal benefit, or a desire to avoid trouble or danger from guards or other prisoners.9 During the Great Depression, as Ethan Blue notes, collective prisoner resistance and radical community were just “fleeting moments” in a repressive environment of atomization and mutual hostility.10 Overcrowding or aging infrastructure, however horrible, and managerial dysfunction and staff disorganization are rarely sufficient on their own to provoke serious disorder unless prisoners come to collectively view these conditions as intolerable.11 Discursive and physical spaces to talk and make connections, the realization of shared interests and the articulation of shared critiques, and the formulation of shared demands are turning points in emergent prisoner resistance.12

The routines and structures that governed daily life at prisons like Kingston Penitentiary, especially the cell block and forced work in large shops, were sites of group interaction that allowed informal networks to circulate grievances and coordinate actions and provided a resource – labour – that prisoners could withhold.13 Prisoners referred to customary traditions within and without the prison in making appeals to group cohesion, through sticking together, the male-gendered fictive kinship of brotherhood, comradery, and solidarity.14 Solidarity between prisoners, however elusive, was a powerful defence against the “disrupted” and arbitrary regime of the prison, as Thomas Mathieson observed.15 In formulating demands, prisoners often selectively adopted and repurposed the criticisms of penal reformers, prison staff, and the media, pointing to criticisms made by these groups to bolster their own claims. This generation of shared grievances and demands often occurred during, or because of, less visible, often non-violent protests like hunger strikes, work refusals, protests, and petitioning by smaller groups of prisoners, and prisoner struggles often continue long after the dust has settled and public attention has moved on from a large-scale riot.16

The 1932 riot has generally been understood through its long-term political and administrative impact, and explanations for the riot offered at the time continue to define historical understandings. Press coverage of the strike and riots presented a sometimes confusing picture, with narratives of a peaceful planned demonstration alongside descriptions of a “howling mob” of convicts wreaking bloodshed and violence. Interviews with former prisoners provided sometimes accurate descriptions of prisoner grievances mixed with sensational tales of destruction and attempted murder.17 The events in Kingston Penitentiary were preceded by highly publicized riots in American prisons and a January 1932 mutiny at England’s Dartmoor convict prison. An international wave of prison unrest had arrived in Canada.18

Official explanations for the riot were not long in coming. The published report of superintendent Daniel M. Ormond blamed the riot on prisoner agitators, including Communists, but Ormond’s primary concern was what he considered the poor training, incompetent management, and “state of lethargy” of the staff.19 During their court trials in Kingston between February and June 1933, the prisoner rioters’ thoughtful and articulate conduct, in arguing for humane treatment and better conditions, shifted public sympathy and persuaded the presiding judges D. E. Deroche and E. H. McLean that the riot was “peaceable” if “tumultuous” and that their grievances and demands were “reasonable.”20 Both Superintendent Ormond’s report and the 1933 trials emphasized certain inmate demands – for cigarette papers, better food, and stronger reading lights, for example – while other demands, such as for an inmate committee or abolition of corporal punishment, were minimized or ignored.21

The question of prison reform spread beyond the confines of the penitentiary, as clergy, bureaucrats, politicians, voters, newspaper readers, and reformers argued over the administration and direction of penitentiaries. Demands for reform and a royal commission were taken up by the press, led by Harry Anderson of the Globe, and bolstered by scandalous exposés by well-educated, élite ex-prisoners like Oswald Withrow and Austin Campbell; Tim Buck’s accusations of an assassination attempt against him during the riot; and harsh criticism of the Conservative government in the House of Commons by penal reformers and parliamentarians including Agnes Macphail, J. S. Woodsworth, and A. E. Ross.22 After the election of William Lyon Mackenzie King in late 1935, the government called the Royal Commission to Investigate the Penal System of Canada, headed by Justice Joseph Archambault and thus also known as the Archambault Commission; its sweeping investigation and final report not only condemned a punitive orientation unguided by scientific and technocratic penological innovations such as classification, adult education, and psychiatric treatment but also chastised federal penal management “for allowing such conditions to prevail.”23

There is a small body of work on the 1932 riot in the criminological or historical literature. Criminological accounts have considered the event very briefly and adopted a comparative focus considerably broader than the riot itself, emphasizing the decisive role of a combination of administrative breakdown, inconsistent regulations, and managerial failure erroneously blamed exclusively on Superintendent Ormond.24 Several theses, also employing a comparative focus, have described the riot in more detail, drawing attention to precipitating causes, including a persistent failure to institute a rehabilitative policy in the penitentiary, and the wider social and historical context.25 Popular accounts of the riot, of the history of Kingston Penitentiary, or of specific famous prisoners stress the lack of basic amenities, overcrowding, and harsh discipline, all of which combined to provoke the riot, and they provide differing and individual prisoner perspectives on the experience of incarceration.26 Histories of Canadian criminal justice and biographical accounts of famous penal reformers have tended to focus on the efforts of politicians, journalists, and reformers to investigate prison conditions and the political and administrative consequences of the riot. The actions and demands of prisoners in these accounts are secondary to the efforts of powerful individuals and governments to enact penal reform. This process culminated with the 1938 Archambault Report, a document that ostensibly marked the decisive shift from a punitive to a rehabilitative model of incarceration in Canada.27

While acknowledging the deliberate nature of the initial strike, all these works present prisoner resistance at Kingston Penitentiary in 1932 as something akin to a “volcano bursting,” in John Kidman’s description, the inevitable consequence of the severe deprivation caused by the “the modern pains of imprisonment.”28 By contrast, the best recent account of the 1932 riot, by Chris Clarkson and Melissa Munn, synthesizes the existing literature, sympathetically contextualizes prisoner protest at Kingston Penitentiary as deliberate strategy, and briefly consider aspects of prisoner organizing.29 However, their account mainly serves to contextualize later prisoner reform efforts and, as with previous scholarship, relies on a small number of official reports and memoirs, which does not fully capture the complexity and breadth of 1930s inmate resistance.

The views of prison officials and reformers weigh heavily on the historical literature on the 1932 riot. As Clarkson and Munn note, there has been little critical re-examination of the published accounts of prison officials and prison reform advocates of this era.30 These official documents and statements reflect the perspective of the individuals who had been responsible for administering prisons or developing penal policy. Accounts by prisoners explaining their actions or the importance of their demands are either missing, obscured, or marginalized in these documents.31 The materials used in this article therefore present a unique source of information, as the penitentiary authorities, as in other moments when power is challenged, produced a considerable volume of documentary material in response to prisoner unrest. There are, however, limits to using these primary sources. Prisoners were generally unwilling to speak candidly, for fear of incriminating others or themselves. Prison records also present generally fragmentary details about the lives of prisoners, and for most of the prisoners in question, incarceration represented a difficult but brief period in their lives. Often guards saw insubordination where there was none and were generally condescending and hostile to prisoners.32

Surviving internal operational reports, punishment records, and reports from subordinate prison officers include detailed descriptions of individual and group acts of prisoner rebellion, work stoppages, protests, and petitions; almost all contain lengthy transcripts of interviews with participants. These records also contain confiscated notes, letters, manifestos, and petitions written by prisoners. As with the program that opened this article, these documents were not permitted by officials and were often intended for an audience of other prisoners.33 The documents are particularly revealing of the attitudes and aspirations the authors thought would resonate with other prisoners. The most important of these documents was a manifesto titled Barbarism and Civilization, a collective document written during 1932. Men clandestinely passed Barbarism and Civilization throughout the prison, and new writers repeatedly made additions in their own hand and often in widely different styles of writing, sometimes repeating or adding emphasis to earlier criticisms and demands. The last line of the document contains an exhortation to spread the manifesto to “good people.”

The interview transcripts created for Superintendent Ormond’s investigation are especially valuable. Ormond interviewed almost every prisoner at Kingston Penitentiary, whether they had participated in the riot or not, as well as the entire staff.34 During these interviews, Ormond made little effort to guide the testimony, asking only that prisoners provide their complaints and their understandings of the riot. Most of the interviewees spoke at length.35 Ormond, newly appointed in August 1932, was pursuing his own goal of disciplining staff and reforming the penitentiary’s administration, and the interviews provided material that was useful to him even if they inform little of his published report. These interviews were also a site of contestation, as prisoners accepted one identity imposed upon them – they did not challenge their status as prisoners – while, in turn, they interrogated Ormond about the purpose of incarceration and penal reform, referring repeatedly to their elected delegates and manifestos and asserting their own lived expertise as a basis for reform.36

Unable to formally organize, and in the face of close supervision and little autonomy, prisoners staging strikes and protests at Kingston Penitentiary faced considerable obstacles in seeking redress of grievances or amelioration of conditions. Close attention to their organizing efforts and struggles is important in part because, as Jordan House has argued, prisoners, as marginalized workers, “experience further erasure even in their exercises of power and acts of resistance.”37 Indeed, within the context of the tumultuous early years of the Great Depression in Canada, the prisoners at Kingston Penitentiary engaged in a kind of politics like other Depression-era protests of the unemployed, relief recipients, relief camp inmates, and evicted tenants. The incarceration of eight members of the Communist Party of Canada is an obvious common element, but this comparison was made by prisoners themselves. Sam Behan, one of the principal leaders of the strike, pointed during his trial to “a riot of unemployed” at Kingston’s City Hall on 24 May 1933, at which protesters demanded better treatment, and connected their struggle to those of his fellow prisoners.38 The prisoners’ insistence on electing representatives, resistance to institutional control and hierarchy, direct and sometimes spontaneous action to force out unpopular supervisors, frustration at forced labour and unsatisfying work, anger and fear for the harms to their body and intellect caused by unsanitary conditions, bad food, and poor medical attention are familiar from other protests at the time – part of what David Thompson conceptualized as “revolutionary indignation” or “politics of indignation.”39 Prisoners, too, were arguing for a more just society and making demands upon the government, arguing in the memorial program that opened this article that only a government “for the people, of the people, by the people” could reform the penitentiary.

“We Are Sitting on Dynamite”: Kingston Penitentiary in the Great Depression

In 1932, Kingston Penitentiary was approaching its 100th anniversary. It was the oldest federal penitentiary in Canada, receiving men from Ontario and women from across the country sentenced to terms of two years or more. Two additional penitentiaries were being constructed by prisoner labour in the Kingston area: the Prison for Women just north of the old prison and the Collins Bay Penitentiary for “reformable” prisoners west of the city. A limestone wall and four towers manned by armed guards surrounded the penitentiary. Its principal entrance was the monumental North Gate, where the offices of the warden and his clerical staff and the armoury were also located. South of this, a massive central dome connected the cellblocks, arranged in a cruciform pattern with north, east, west, and south wings.

The cellular system had been completely rebuilt in the early 20th century. Every cell was roughly five feet across by ten feet, equipped with a folding desk and bed, a 10-watt light bulb, and brass sink and toilet fixtures. The cell blocks consisted of four tiers of back-to-back cells, called ranges, oriented toward the exterior walls, which allowed some light to enter from vertical windows that stretched from floor to ceiling. Running between these cells were surveillance galleries or corridors from which guards could watch prisoners through small spyholes. Flanking the cellblocks were the prison hospital to the east and the kitchen and chapels to the west. South of the cell block were workshops, also arranged in a cruciform pattern, with shops on two stories in four wings that met in a central gallery called the Shop Dome. The power plant that electrified and heated the prison also formed part of this complex. Parallel to the eastern wall was the Prison of Isolation – the former high-security ward – consisting of six ranges on three levels of ten-foot-by-ten-foot cells. Parallel to the western wall was the former asylum building, in the process of being converted into workshops and cells before the riot. The women’s prison was in a detached cellblock to the northwest. Open spaces were used for garden plots and for the “bull-ring” where prisoners paraded in a circle for exercise.40

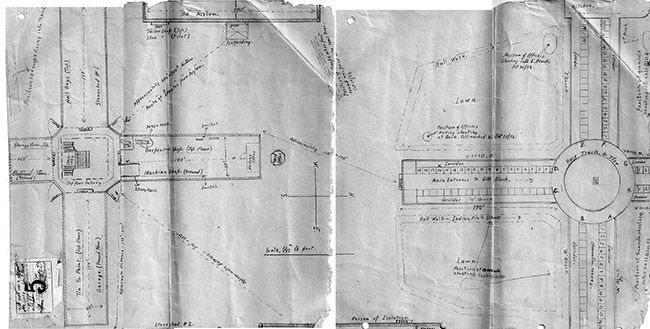

A map of cell blocks (right) and workshops (left) of Kingston Penitentiary, showing the exercise yards and locations where officers fired upon the cellblock, produced in early 1933.

Superintendent’s Investigation, sfpb, csc fonds, rg73, acc no. 1983/84/291, box 30, 4-15-10, part 1, lac.

The prison’s daily routine was dominated by several apparatuses of control, including the silent system, strict rules of conduct, and convict labour. These were foundational to the penitentiary and had been adopted when the institution opened in 1835. The initial high hopes that the penitentiary would remake the incarcerated into model citizens had dulled over the 19th century, yet prison administrators remained confident into the 20th century that regulation of criminality and the moral reform of convicts was still possible through strict discipline, isolation from society, and productive labour. Ideally, some prisoners could be taught a trade, while the disciplinary system would enforce habits of industry and obedience.41 The focus on labour and strict rules had been given new life by post–World War I penal reform focused on the standardization of regulations, greater professionalization of staff, and crackdowns on trafficking in illicit goods. The superintendent of penitentiaries from 1919 to 1932, William St. Pierre Hughes, held that strict discipline – leavened by the occasional concert, the promise of early release through good conduct, and limited privileges – would bring about the rehabilitation of prisoners.42

During the Depression, “strict economy” was imposed upon the Dominion Penitentiaries: requisitions for goods and equipment were curtailed, and the hiring of staff was halted.43 At Kingston Penitentiary, the senior officers were nonetheless all recent appointments. The acting warden, Inspector of Penitentiaries Gilbert Smith, had assumed his position on 20 January 1932. The deputy warden, a career officer named Matthew Walsh, and the chief keeper, Norman Archibald, had both been promoted in late 1931. The former warden, J. C. Ponsford, warned Smith that it “would take very little to start trouble” at the penitentiary, and Penitentiary Branch headquarters in Ottawa issued orders against “any slackening of discipline, nor any shirking of duty.” Smith found considerable “uneasiness” among the officers, who were upset about wages, non-permanent appointments, and increasing numbers of prisoners.44 The penitentiary, already overcrowded in late 1929, had grown from an average of 750 inmates that year to an average of 950 prisoners by October 1932.45 The staff contingent, however, remained stable at 90 custodial and 35 work instructors, in addition to administrative staff. To meet this growth in prisoner numbers, beds were placed in the main-level corridors of the cell blocks, and wooden dividers split the cells within the Prison of Isolation, so that every second prisoner used a bucket instead of a toilet. Deputy Warden Walsh felt these changes “forced us back 30 years” and precipitated severe sanitary and disciplinary issues, making it increasingly difficult for staff to monitor prisoners and enforce the regulations.46

Then as now, the majority of the imprisoned at Kingston Penitentiary in the 1930s were poor and unskilled, and many were jobless at the time of arrest and conviction. Almost half had previously been incarcerated, at either a penitentiary or a reformatory, and these men experienced constant suspicion from police and employers before their conviction. Many of these individuals could not afford legal representation at trial and, often having been caught in the act of theft or burglary, said little in court while magistrates disposed of their cases.47 Those men who did speak in their defence offered a wide range of explanations for their criminality that connected their individual circumstances to their observations of systemic social injustices. Ami Lamontagne, convicted of robbery, told a judge, “I was picked up on suspicion when the restaurant I worked at was robbed. My employer found I had a record and I was fired.” Others, like Francis Sheehan, convicted for an armed robbery, were veterans whose meagre pensions and war injuries had made supporting their families difficult without resorting to desperate means.48 Disgraced police officer and bank robber Ernest Bennett and his partner in crime, Joseph Malcovitch, told the presiding judge during their trial that they had turned to robbery because they were sick of “hunger and begging” in “this country [which] makes no provision for its unemployed.”49 Some, like Alfred Garceau, a prominent inmate leader in 1932, struggled with addiction and opposed their lengthy sentences and mistreatment at the hands of police and courts, pointing out “that [stock] brokers and others injure the public, whereas he only injured himself.”50 Six hundred and thirty-six of the male prisoners sentenced to Kingston Penitentiary in the year prior to October 1932 had been convicted of various forms of larceny, mostly armed robbery, car theft, break and enter, theft, and false pretenses, and the majority of sentences ranged from two to fifteen years. Escape from custody or prison, assault, crimes of sexual violence, murder, manslaughter, and possession of narcotics represented another 221 prisoners.51 There was also an intensifying retrenchment against parole, and far fewer prisoners were paroled in 1932 than in 1929.52 Prisoners felt that “parole had been cancelled” owing to mass unemployment, and some accepted that it would be “easier on the people outside” for them to stay in prison. Nonetheless, the reality that a few, wealthy individuals were released early convinced many inmates the system was rigged: “It is possible that with money and influences you get out. The poor people have no chance.”53

The incarcerated were subjected to a series of “ceremonies of social exclusion” that marked them as convicts.54 Their heads were shaved, and they were dressed in the standardized uniform adopted in 1920: baggy brown pants and formless brown jackets, each item marked prominently with a stencilled identification number. Prisoners were limited to writing one two-page letter a month to a single family member, on penitentiary letterhead, and were limited to a family visit in a partitioned room, called a “cage” by prisoners, with a guard present, once every three months. Letters to and from family were censored or withheld if they violated rules about content. Magazines were heavily censored, and newspapers forbidden, but the library had a substantial collection of older books, and for educational purposes individuals could acquire new books. A few guards and inmates had the “monopoly” on smuggling these items into the institution, a testament to the demand for outside information but a risky, secretive practice that was expensive and exhausting for many prisoners.55 Although there were periodic concerts and entertainments around major holidays, the Depression largely ended the practice; the first concert prisoners had enjoyed in a year occurred in early October 1932.56 A tobacco ration was given to all prisoners who smoked, but for reasons unclear to prisoners and even to Superintendent Ormond no cigarette papers were issued, forcing prisoners to use toilet paper, scraps of letterhead, or pages ripped from books to roll cigarettes.

The silent system imposed on prisoners made it a violation to speak or otherwise communicate with one another, and even carrying on a conversation with an officer required permission. Although intended to prevent communication of any kind, limiting the opportunities for escape, disturbance, and inmate sociability, the silent system was easy enough to work around. A complex array of techniques – hand gestures, voice throwing, the passing or “fishing” of written notes or “kites,” the use of code and parley, and the connivance of trusted inmates – allowed inmates to communicate quickly across the prison. It was also by these means that messages and inmate manifestos, most notably Barbarism and Civilization, were disseminated and debated. The silent system was inconsistently enforced, and this selective enforcement by officers was just as frustrating as the inability to talk, as one inmate noted: “I have been written up four times for talking. I called the Deputy up once and he saw the injustice and cancelled it. He claims he does not object to a man speaking yet I have been punished.”57

Equally unfair, opaque, and inconsistent to prisoners was the labour system of the penitentiary. According to Austin Campbell, “The motto is ‘work and more work, and then more work.’”58 Prison labour was compulsory and provided the paramount system for organizing the prison. The entire social world of the prison was segregated by what prison staff and inmates referred to as work gangs, who ate, bathed, and dressed together. Much like life in any other factory, the workers’ concerns and actions tended to involve the men they knew and worked beside day after day, providing a sense of community, shared interests, and even friendships.59 Barred since the 1880s from competing with the capitalist market, prisoners worked on government mailbags, boots and shoes for police and military, and equipment for other federal government departments. The remainder of prisoners worked at maintaining the prison and its denizens through quarrying and stone cutting, cooking, uniform production, and laundry. Some inmates assigned to clerking, bookkeeping, and running messages occupied the cells at the start of ranges. In the lead-up to the October 1932 strike, inmates holding these positions had ample opportunity to pass messages and enforce collective decisions on the range.

Work assignments were made by Deputy Warden Walsh, whose duties included the discipline of convicts, security, and industrial management of the penitentiary. The deputy warden, aided by the chief keeper, assigned work based on previous labour and carceral experience, but the need for bodies in specific gangs generally trumped other factors. Prisoners resented the lack of control they had over the labour system. George Skelly protested bitterly: “I got a job here alright – the Stone Shed – and was put there when I had no knowledge of the work.” Many inmates had injuries or illnesses, such as respiratory diseases, missing fingers, war injuries, and back injuries, that were often ignored, and such men were often placed at jobs unsuited to or painful for them. Requirements for placements or transfers seemed capricious and hypocritical. Prisoners were told they could get not get a transfer because of bad conduct, but improving conduct did not lead to transfers to more desired positions. Mathieu Bedard, who was serving a life sentence and worked as machinist in the canvas shop, summed up this frustration: “I have worked at mail bag machines for years. What did I get? Nothing.”60

The context of the Great Depression altered the conditions of work for convicts but not uniformly across the institution. Kitchen and laundry workers complained that they worked twelve hours a day with only Sundays off.61 Workers on the farm or the skilled masons and carpenters labouring on construction sites expressed more satisfaction with their work. Prisoners in the industrial workshops inside the penitentiary, however, experienced unemployment and make-work projects, and the increase in prisoner numbers exacerbated the collapse of government contracts during the Depression. To accommodate this increase, two men were assigned to do one man’s tasks in some workshops, while others worked only a morning or evening shift, and some workers were transferred to paint walls or break rocks. Both penal administrators and reformers were concerned about the idleness evident in prison workshops, believing, as Withrow did, that work, “steady, soul-satisfying labour, is the salvation of any man.”62 Few prisoners complained about idleness in these terms, however, and the men often used the lack of work to their advantage to smuggle notes and read manifestos. The greater concern was the boredom, the lack of alternatives to work, and the tendency of guards to report even prisoners who, like Alex Mustard, would “sit on a chair, not bother anybody and mind my business” when done their tasks.63 Younger prisoners often expected that they would learn a trade while incarcerated, a view fostered by judges and social workers, but the experience of prison work often left them disillusioned, as John Farr fumed: “I was sent up here by a Judge to learn a trade [but] they have taught me nothing.”64

Prisoners saw no use in in taking their complaints to the instructors, guards, and the deputy warden. Robert Smith described his experience in June 1932 of attempting to secure a change of work: “he [the deputy warden] took me and put me on the roof. I said I did not want to go on the roof. They threw me in a punishment cell … I do not think I got a fair break.”65 To protest, prisoners would deliberately work slowly or poorly, a behaviour in common with relief workers doing forced labour.66 In the months before the 1932 protests, this practice became well organized: for instance, Murray Kirkland convinced his fellow workers in the canvas shop to “spoil” Superintendent Ormond’s first inspection in September 1932 and embarrass their supervisors by deliberately making mistakes.67 Prisoners would also “beef” to get their case taken directly to the warden, who was viewed as being a “fair man” and more sympathetic to prisoner requests. Prisoners broke tools, yelled at instructors, feigned illness, and stuck to their refusal through long days in solitary confinement. These individual challenges rarely succeeded, however, and guards tended to see these individual acts of resistance as the actions of “liars and cheats.”68 The strikes and riots that took place in 1932 and later should be understood in the context of mass organized “beefing,” of escalating activity to demand change. In the prisoners’ estimation, a large enough strike would guarantee the warden’s presence and allow the inmates to make their point directly.

Prisoner work gangs were organized hierarchically by prison staff and instructors. Experienced prisoners, often recidivists, who had worked in prison workshops before were placed in key and important positions in shops.69 These lead hands exerted more day-to-day influence over the shop than the officers. Apart from experience and training, they were expected to exert control and maintain discipline among the younger or more troublesome prisoners. Often they received illicit gifts and extra food and tobacco rations from staff and could be very loyal: Fred Moore, an unofficial instructor in the shoe shop since his conviction in 1925, rallied prisoners against a strike in 1927 and tried to do the same during the strike of 1932.70 Individuals in these positions were called “favourites” by other prisoners, who resented their privileged treatment. In the canvas shop, according to Murray Kirkland, “there were a lot of fellows who were favourites of [the instructor, George Sullivan] … They get the easy jobs sitting back doing nothing, he chooses me to do the heavy jobs.” To challenge the order was to risk severe punishment, as Kirkland discovered in early 1932: “I objected to [the favouritism] and went up to Mr. Smith; I was thrown in the hole again until I would consent to this system.” Ultimately, Kingston Penitentiary, in William Murrell’s words, operated by “intrigue between men and officers. You couldn’t single out one individual officer. It is the custom and the method of this institution.”71

Another system of control in the prison included the much hated “rats,” or prison informers. Many prisoners felt that rats were simply men lacking in moral fibre or courage, but they were in fact organized and supported at the highest level. Denied the hiring of new officers, Deputy Warden Walsh and Chief Keeper Archibald expanded the existing “rat system” with the inducements of extra tobacco and food rations, maintaining a fund within the administration budget for such purposes. Inmates who had been victims, real or imagined, of rats complained bitterly of the system: “[a rat] will tell Deputy Walsh or Chief Archibald and bingo into the hole the fellow goes – just on the word of one guy – a rat.” This situation ensured that fear and paranoia ruled the day-to-day in the prison. The anonymous accusations were widely resented, and unsurprisingly prisoners who had ratted, or were thought to have ratted, were terrified by the possibility and reality of a revolt.72 Prisoners had no accurate means of gauging who was a rat, and before and after the riot, prisoners who voiced a lack of enthusiasm for protest were denounced as spies. In the case of Moses Aziz, a Syrian immigrant, his religion and “foreign” background was enough to make him afraid he would be targeted as an informant.73

The prisoner community of Kingston Penitentiary was riven by factions and animosity between prisoners. Sometimes these divisions took the form of conflicts between former friends or associates, or feuds driven by real and imagined slights. Hostility against certain prisoners was intertwined with collective understandings of class, race, and masculinity. Rich, well-connected men, convicted of white-collar crimes like embezzlement, were treated with hostility by most prisoners, and even those former and current prisoners like the doctors Oswald Withrow and Lyman Rymal who were well regarded by other prisoners and assumed to be “on our side” were still thought to be shielded from mistreatment and punishment by their connections, which could make it “too hot” for the administration if they complained publicly.74 Indigenous prisoners from communities remote from southern Ontario were often ignored by other prisoners, and several testified that “no one had spoken” to them about protesting.75 Black prisoners like John Evans, who took a prominent leadership role during the strike, claimed he had been accused of theft and even assaulted by another prisoner because of his race.76

The criminal careers of the incarcerated also generated a shared ethic between individuals, however fragile or prone to disruption the resulting connections might be. “Rounders” or “in and out men” like Louis Gallow, Ardwell Perrin, and Philip Roberts, men who had frequently been on multiple “trips” in and out of prison and knew well the unwritten customs and survival strategies of the penitentiary, were well respected, and prisoners convicted of robbery, burglary, car theft, escape, or resisting arrest were frequently the leaders of prisoner organizing in this period. They often embodied a specific set of masculine values such as having self-control, being assertive and physically brave, fostering camaraderie, telling “a man to his face,” maintaining self-respect and personal dignity, resisting authority, and helping others who resisted authorities.77 Knowledge of the law or society and experience of the world, or at least other prison systems, were also highly valued. Conversely, prisoners who failed to conform to these values, who were considered servile, obsequious, or cowardly, or had committed crimes that were considered abhorrent by other prisoners, especially sexual assault against children, were ostracized and shunned.

These divisions and common values influenced participation in collective action. Supporting protest provided a powerful, collective ethic and fostered feelings of community and solidarity, but prisoners had many reasons for refusing that support. Some considered it foolish or dangerous to oppose the prison authorities and the government. Prisoners who disliked certain delegates refused to support the 17 October strike because of this animosity, and William Kunz considered he had “a difference of principle to these agitators.”78 Prisoners who refused to support the strike were threatened or were bullied, harassed, and in several cases assaulted in the months after 20 October 1932. Roberts, for instance, led several other prisoners in an assault on a suspected “rat” in July 1933.79

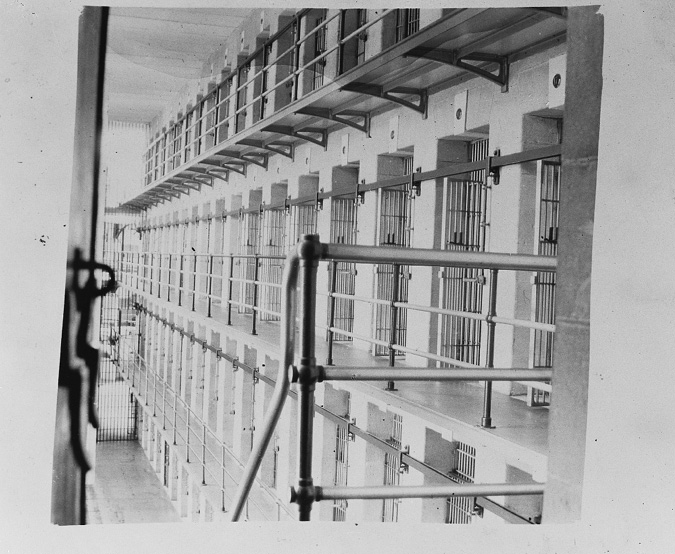

A cell block inside Kingston Penitentiary, typical of the early 1930s.

Globe and Mail fonds, fonds 1266, item 31552, City of Toronto Archives.

For most prisoners, however, the guards were the most serious problem. John Evans was clear in his testimony that the guards were the ones “down on all the colored folk here,” and Jewish prisoners like Sam Stein and Jacob Miller thought “we Jews are not treated fairly here by the guards.” The incarcerated Communist Sam Cohen concluded, “it is the general impression that the bosses are not so bad as the foreman.”80 The guards’ daily conduct was intensely frustrating to prisoners, most of whom had, at least once, been the target of seemingly random harassment by certain officers. To keep control and enforce discipline, officers regularly asserted their power and authority, looking out especially for signs of disobedience or defiance. Inmates in their testimony frequently referred to the “petty persecution” of guards and complained of being “bulldozed,” “ridden,” “nagged,” and “picked on.”81 Some guards were praised by prisoners for being fair, strict without being cruel, or sympathetic to their plight, but the majority of guards were considered cowards and bullies in equal measure. Prisoners especially complained that guards, in the words of Indigenous prisoner Arthur Currie, would “not talk like human beings at all [but] as if you were a dog.”82 In some cases, guards so distracted and bothered inmates at their labours that accidents, failure to meet targets, or injury occurred. Prisoners found themselves pushed past the limits of their patience by the constant harassment, as Louis Gallow found in August 1932: “I threatened [Guard Martin] with a pair of scissors and told [him] that if he did not lay off me, I would finish him. For that, I was shackled to my bars instead of working.” In assailing the mean-spirited enforcers of the rules, Barbarism and Civilization concluded that “if inmates are treated like beasts it is expecting a little too much to hope they will become good citizens.”83

It was not just the foul language and bullying that prisoners found difficult to bear. Officers ruled through an empire of papers. Written reports, called “dockets” by prisoners, were used as evidence in the daily warden’s court and had serious consequences. A bad report could lead to weeks in solitary confinement, shackling to the cell bar, corporal punishment, the denial of parole, and, most frequently, loss of remission. Remission, or earned time off a sentence, accumulated at a rate of one day off for every month of good conduct and industry, so losing a week of remission translated to months of good behaviour wasted. The process of reporting and the warden’s disciplinary court were utterly opaque and stacked against inmates. One prisoner summarized these suspicions well, noting that regardless of “whether you are guilty or not, you cannot explain this to Warden. The officer’s word is always taken.”84 To the officers, this was the natural state of affairs and their word “should have been enough,” according to guard Ralph Jenkins.85 Officers did not have to be present when their reports were read or presented to the inmate, essentially putting officers on the same moral plane as the secretive rat in the eyes of the confined.

“There Are a Few Small Things That Would Do a Lot of Good for Me and the Others”: Prisoner Demands and Reform Plans

Throughout the mass uprising that marked 1932 and after, prisoners formulated and circulated reform plans and demands for change. Some of these demands were programmatic and collective, as found in Barbarism and Civilization, while others were highly individual and conveyed to Superintendent Ormond during his investigation. Some demands, such as for prisoner after-care, industrial training, wages, and recreation, anticipated later reforms and recommendations made by the Archambault Report. Others, like inmate committees and the abolition of corporal punishment, went far beyond what reformers envisioned. Some royal commission recommendations, such as calls for classification and segregation, psychiatric care, adult education, and religious instruction, are never mentioned in the interviews.86 In general, prisoners rarely referenced contemporary politicians, reform groups, or service organizations in their manifestos and testimony, even if some of their complaints and demands echoed those of penal reformers. For instance, Woodsworth’s observation in Parliament that there was “one law for ‘big criminals’ and another for ‘little criminals’” is reflected in prisoner complaints about unfair job assignments and parole, and some sections of organized labour had proposed abolition of corporal punishment.87 Prisoners relied on their own experiences and identities to lend authority to their demands and collective action. Veterans demanded better treatment because of their war service and resultant shell shock and wounds, as Noel Charron argued: “Does not a returned soldier deserve a little consideration?”88Some pointed to their status as British subjects, arguing, as Everett Waring did, that “fair play” and “justice” were owed even to convicts.89 Most consistently, prisoners asserted that, as working-class men and as human beings, they were entitled to humane treatment and personal respect, no matter their behaviour before and during their incarceration.

Another persistent element of prisoners’ critiques of the penitentiary was a demand for fairness or equality, what they often dubbed a “fair deal” or “square deal.” As Mathieson observed of Norwegian prisoners, demands for equality or fairness not only emerge from unequal treatment and distribution of resources within the prison but are part of “the ‘raw material’ brought in from the outside” – that is, the norms and values of their pre-incarceration communities.90 Prisoners at Kingston Penitentiary expected to be treated honourably by both fellow prisoners and the officers, in a manner that connected manhood with honesty, keeping one’s word, and impartiality. Attacks on “favouritism” reflected a desire for every prisoner to receive the same standard of disciplinary treatment, similar privileges or punishments, and equal distribution of goods. “Every man should have the same opportunities here,” summarized John Maurice.91 Prisoners demanded that work placements, transfers, and paroles be based on need, merit, ability, and length of sentence, as regulated by transparent and consistently followed rules. In this respect, prisoners at Kingston Penitentiary shared much in common with prisoners in other periods but also with relief recipients and workers demanding fairness of treatment and distribution of work and resources.92 Prisoners like Austin Campbell, a former stockbroker and writer, and a beneficiary of favouritism, were unsurprisingly hostile to these demands, and Campbell celebrated that the penitentiary system, especially the more relaxed, reform-oriented low-security prison camp at Collins Bay Penitentiary, allowed “biologically inherent” social “grades” to flourish.93

This desire for fairness is a notable feature in inmate plans to fix the work system. Removing favourites was the most popular step. A prisoner in the canvas shop, Ronald Jeskey, suggested, “I would kick on the four or five men that have the Instructor’s ear so I have a chance here.”94 Hiring qualified instructors was another potential improvement that inmates supported, and actually implementing vocational training and installing modern equipment was a third. Ultimately, prisoners demanded the autonomy to choose their own job placement or trade and to request and receive transfers. Kitchen workers on strike in December 1932 put this demand succinctly in their petition: “the medieval system of the rights of a seigneur shall not hold sway in this institution any longer.”95 Many inmates suggested a pay system, not just as an incentive to good behaviour but as an aid to prisoners after release; as one inmate noted, “the $10 we get now is only enough to buy another gun.”96 Barbarism and Civilization repeatedly suggested an eight-hour day, “just like outside,” and a pay system “like in all the US stirs” – a reform that would abolish the work-based “slavery” that “Canada makes a medium for ‘normal’ rehabilitation.”97 For prisoners, pay promised the possibility of choice and autonomy within the prison; as Barbarism and Civilization and individual prisoners proposed, they could use the money they earned to pay for magazines and books, extra amenities, and outside medical help, to fundraise for entertainment, and to support their families.98

The most elaborate proposal for reforming prison labour came from Alfred Garceau, one of the delegates elected during the riot. His plan, For the Reform of the Penal System of Canada, was widely distributed throughout the prison in the summer of 1932 and proposed reshaping the penitentiary around vocational and educational training. Central to Garceau’s plan was “the substitution of incentives for repressive rules.” Every inmate would receive personal and industrial assessments on arrival and, after a month of good-conduct probation, would be fitted to a desired trade at a wage close to the market rate. At all times the prisoner would apply himself to “productive work, being subjected to regular strict examinations for general proficiency.” Garceau suggested that self-governance and the passing of examinations and tests – not conformity with “rules, empty of morality” – would finally qualify the inmate for parole. Finally, industrial and agricultural colonies of paroled convicts should be set up to re-establish prisoners and provide every parolee with a job until their sentence was complete. Garceau ended with a reminder that no rehabilitation was possible “except for that which comes from within.”99

A persistent complaint of prisoners was the lack of anything else to vary the tedium of prisoner labour and silence. According to Sam Behan, “it is just a case of cell to work – work to cell, day after day, year after year, without a moment’s recreation – nothing to divert the mind excepting reading – one cannot read all the time.”100 Duncan MacGillvery, a convicted stockbroker, concluded that “you will say the men are suffering from excitement, but really, it is the lack of excitement.”101 Dan MacDonald, a thief and hobo who also claimed to be a former Industrial Worker of the World, felt that “mental depression and irritation are the cause of this outbreak. It is the monotony that wears us down.”102 Summarizing the feelings of many prisoners, Barbarism and Civilization’s writers questioned why prisoners were so repressed of every “natural” impulse – toward sociability, rest, recreation, and knowledge – when “even the rulers of ancient Rome recognized the need and gave the slaves circuses. Yet in this the fourth decade of the twentieth century a thousand human beings are hearded [sic] in this institution under conditions which amount to complete denial of the fact!”103

Against this regime, Barbarism and Civilization made a basic assertion: “Even if society’s [sic] incarcerates thousands of its members in prison it has no right to wreck and ruin them physically and mentally in the process.”104 Prisoners attacked the penitentiary for making them physically worse – for not providing exercise after having them sit at machines all day, for harming their bodies through labour, and for not sanitizing the prison properly. Barbarism and Civilization asserted that “recreation was a biological and animal necessity.”105 Prisoners found it “demoralizing” to learn they took treatments and procedures for segregation of venereal disease more seriously than the guards.106 Others, like William Holfner, a war veteran serving a three-year sentence for possession of narcotics, demanded that the penitentiary’s policy of forcing individuals struggling with substance abuse to go “cold turkey” should be replaced with “what they call the ‘taper off’ approach.”107 Even those prisoners otherwise unable or unwilling to articulate other kinds of grievances expressed profound fear of the prison doctor and of dying or being crippled as a result of his perceived neglect or incompetence and the overall environment of the prison. Withrow, who had worked in the Kingston Penitentiary hospital in the late 1920s, put these fears succinctly: “men are done to death by the system.”108

In attempting to combat this bodily breakdown of the individual, prisoners demanded the end of all practices that they viewed as humiliating, denigrating, and limiting of their self-respect. Prisoners insisted that their demands for cigarette papers, newspapers, smoke breaks during working hours, an increase in letters and family visits, the cancelling of prison haircuts, the abolition of the silent system, and the end of guard mistreatment would stop the degradation and humiliation they felt. Prisoners desired organized social activities such as baseball, inmate bands, and radio shows, and not just because they would break up the daily routine. They would also allow new forms of self-expression and self-governance previously forbidden in the penitentiary and provide them with personal freedom and autonomy, which, some argued, existed already in Ontario reformatories like Guelph and Mimico and in American prisons.109 This insistence on social activity outside guard control represents a form of what Charles Bright called “winning distance” – the incarcerated person’s need to be away from staff control – while also echoing the then-contemporary progressive critique that the prison needed not to isolate prisoners from the community but to model itself after the community.110

More dangerous, at least to the penal authorities, were the repeated critiques of punishment made by prisoners in the penitentiary. The inmates assailed both the punishments – whether solitary confinement, shackling to the cell bars, or corporal punishment with the paddle or lash – and how they were administered.111 A persistent demand made by prisoners was to limit or modify the guards’ ability to report a prisoner, including implementing a court system “in which a man has a chance to defend himself.”112 Even more persistently, prisoners demanded the removal of the warden’s autocratic and unaccountable power to order corporal punishment and segregation. Some prisoners suggested the warden’s powers should be replaced by a disciplinary board, including civilian and inmate representation. Another frequent suggestion was to send all corporal punishment charges outside to a judge or magistrate, or to have civilians visit the penitentiary to supervise punishments.113 The abolition of the lash and the prison paddle was the most popular demand, made in Barbarism and Civilization and in the testimony both by individuals who had suffered it and by those prisoners, especially younger men, who had only witnessed or heard of the resulting injuries.114 Regardless of the specific form, any of these changes, if implemented, would shift the balance of power within the penitentiary and rob the officers of their most potent tools for controlling disobedience.

Perhaps the single most potentially destabilizing demand that inmates put forward was to have an active role in the management of the penitentiary. Barbarism and Civilization repeatedly references a desire for an inmate committee or welfare league “to protect our interests.” Several prisoners who had been confined at Auburn or Sing Sing and had served in the Mutual Welfare League offered their services to formalize a system of inmate representation.115 Norman Teetzel, one of the spokesmen for the prisoners during the October 1932 riot, felt such representation “should be continued, so that the inmates would get fair play.”116 Other inmates suggested “three inmates per shop … to help run the works … would make us like lambs.” Harvard Murray, a Stone Shed worker, thought a “prisoner welfare league” could organize sports like boxing, run a canteen, take care of sick or elderly inmates, and ensure “an institution that allows a man to start off with a new leaf.”117 The belief that popular democracy was necessary to protect against arbitrary power and ensure compliance with demands was not an isolated concern of prisoners during the Great Depression, as is evidenced by similar efforts at relief camps.118 Superintendent Ormond’s response to all of this was blunt: “If we give them that, what will they want next?”119

The collective critique made by prisoners is especially revealing of their attitudes toward rehabilitation and the purpose of incarceration. Describing their understanding of the purpose of incarceration, the writers of Barbarism and Civilization argued that the penitentiary system was supposed to “reform him (or her) and set him free in a given period with a new and better outlook on life and a keener appreciation of his duty and behaviour to his fellow man.” This laudable aim, however, was “smothered by a tangle of persecution, hard routine, distrust.” During the post-riot investigation, prisoners demanded to know from Superintendent Ormond what he thought prison was for, and they criticized the numerous ways it caused harm instead of helped. As one young prisoner stated, with some understatement, “If they have in mind a certain reconstruction of man here, there could be a lot of improvements.” That these critiques were so frequently made, especially to challenge abuses, indicates that the reformative image of the 1930s penitentiary was taken seriously, even if the reality consistently failed to match the rhetoric. As a teenage first-time prisoner put it, “my complaint is against the prison, as a whole. It has failed in every way imaginable.”120

“I Am Not Fighting on My Own Behalf, but for All the Boys Here”: Organizing Prisoners

Superintendent Ormond’s official report after the October 1932 riot pointed to a pattern of strikes and disturbances, starting in 1921, that he thought showed an escalation of prisoners learning to become “well organized and work [in] unity … to attain their desired objects.” Historians have echoed these conclusions, pointing to earlier acts of collective resistance going back to 1920.121 Ormond’s chief evidence for this argument is that some prisoners active in leading earlier strikes were present at Kingston Penitentiary in 1932, because they were either recidivists or serving long sentences. Certainly a prisoner like Louis Gallow, a participant in the October 1920 “mutiny,” was part of this living tradition, even if the demand of the mutineers – to reinstate guards who had been dismissed for smuggling contraband – bore little resemblance to later protests.122

It is difficult, however, to gauge how much influence the memory or experience of earlier strikes had on later events. Ormond, for instance, considered the 22 January 1927 strike to be a major precursor of the 1932 events. Intended by the strike leaders to improve the quality of food, the earlier strike failed to gather support from most prisoners, many of whom booed and resisted the small number of strikers in the mailbag, tailor, and masonry workshops. The staff response was swift and brutal, with striking prisoners given corporal punishment and months in solitary confinement. Many of the ringleaders were transferred in November 1929 to Saskatchewan Penitentiary and thus were not at Kingston Penitentiary in 1932. Some participants, like Ernest Snell, refused to talk about their experience of the 1927 strike, whereas others, like Denton Garfield, who had been one of the strike leaders, bitterly resented having been a part of it. Garfield told Ormond, “It did me no good.” He refused to join the strike on 17 October 1932, feeling it would jeopardize his chances for parole.123

Several major incidents at Kingston Penitentiary in the year and a half before October 1932 point to a changing attitude amongst the inmate population toward their treatment and growing organization, evident in the circulation of propaganda and expanding protests. An August 1931 escape attempt appears to have been much more influential on later prisoner organizing than the 1927 strike. A group of six prisoners, including Kirkland and Garceau, manufactured weapons in the blacksmith shop and attempted to incite an insurrection or disturbance to support their escape. Garceau claimed he had hoped to return to the penitentiary, armed with a machine gun, to liberate other inmates. However, some of their confederates got cold feet, and the plan was “ratted out” by several long-term prisoners.124

The potential escapees were all punished with several months in solitary confinement and, driven to contemplation, experienced something akin to what Robyn Spencer has described as “mind change,” where personal transformation breeds political inspiration. Kirkland felt the escape attempt had been “a foolish mistake,” and Garceau learned that “you have to get everyone involved [in planning] or nothing gets done.”125 Other prisoners noticed that these men were different once returned to their workshops. Joseph Insenga, a polyglot prisoner who would translate notes, letters, and texts like Barbarism and Civilization into German, Spanish, French, and Russian for other inmates, believed they had “accepted [the penitentiary] is to be [their] home – and you must improve your home if it is falling apart.”126 One of the members of the escape plot, John O’Brien, was kept in solitary confinement for a year, and his treatment became a point of contention among the prisoners until 1933. The 1931 escape attempt also convinced the staff, as keeper James Donaghue put it, “that any trouble would be a smokescreen for escape,” and the staff, from front-line guards to senior officers, had actually underestimated the scale of inmate resentment.127

The group of inmates involved in the escape attempt were returned to their regular cells and work shortly before the arrival of eight members of the Communist Party of Canada to Kingston Penitentiary in early 1932.128 Warden Smith gave the Communists “a stern talking to” and dispersed them into different workshops, ostensibly to make it easier to supervise and isolate each man.129 Thomas James, a kitchen worker, felt that “[trouble] first started when these men – Communists – were sent in this place. Throughout the institution – lay bills were written in the magazine and it went throughout the institution – anyone can read them.”130 Harold Eden, while noting that “this was brewing in 1928 and 1929,” felt that “it took the Reds to kick the nest up.” There is some evidence of mutual political education involving Communists. Several inmate letters were intercepted in the summer of 1932 that contained invitations to join a reading group led by Tim Buck in the blacksmith shop, and several prisoners said they were members of “The Organization,” a larger circle of prisoners interested in reading economics and political articles found in Harper’s and Collier’s.131 Barbarism and Civilization, although a group document written by many hands, begins with many favourable references to historical materialism and support for Soviet prisons, and Buck in his memoirs claimed he started a five-point petition of “conservative” demands that got the prison “pulsating.”132

It is somewhat difficult to gauge the impact of the Communists inside the penitentiary. Buck relates in his memoir that prisoners asked him to provide information about communism, though some viewed it as “racket.” Individual acts of disobedience before and after the riot included inmates like Philip Roberts or John Farr persuading their fellows to sing “The Red Flag” at work, or small groups shouting “Bolshevistic” slogans – behaviour that was seemingly aimed at antagonizing guards. Whether they agreed with Marxism-Leninism or not, prisoners who demanded reform considered the Communists, especially Buck, Sam Cohen, and Malcom Bruce, to be “good men” who listened and “got along with the boys.”133 As in relief camps and unemployed organizations, the most significant Communist contribution was undoubtedly the creation and dissemination of literature combined with the articulation of a project of demands.134 This circulation of propaganda had an appreciable effect, as well, with several officers noting a change in inmate attitudes. Guard H. Robinson commented that during the spring and summer of 1932 the inmates “did not seem to be under any discipline.” Surviving defaulter sheets, which summarize inmate offences, show an increase in reports and punishments in the summer and fall of 1932 for “insolence” and “refusing to obey orders.”135 Summarizing this new attitude, Buck claimed that prisoners had decided collectively they had “no chance of getting away from here by escape or parole, so we might as well see that we can live like human beings when we are in here.”136

Between 13 and 15 August 1932, the 200 inmates in the Prison of Isolation staged a hunger strike over maggots in the porridge. This was the only most obvious and immediately revolting of the conditions in the Prison of Isolation. The wooden partitions, bucket toilets, and lack of running water were a constant source of irritation and misery. Food, if it did not arrive spoiled, was frequently cold when served, and inmate servers, with the connivance of staff, were accused of stealing from food trays. The Prison of Isolation also maintained a reputation as a punishment detail for “incorrigible” prisoners, a reputation reinforced by the unsanitary conditions. The hunger strike prompted intervention by senior officers, who personally took the time to interview the participants and promise change. To the imprisoned men, this demonstrated the effectiveness of the protest. Inmates were also aware that the Prison of Isolation was looked upon unfavourably by staff, adding legitimacy to their protest. In the wake of the riot, prisoners kept in the Prison of Isolation, like Willard Milich, successfully pressed Ormond to abolish the ramshackle cells, having learned that “[our treatment there] is a sore one with you as well.”137

In August and September 1932, prisoners attempted several times to make collective demands through delegates. Spokesmen are not unusual in prisoner protest, but these efforts to choose consistent representatives from across the penitentiary was novel, and possibly the result of Communist influence.138 The first instance, at the end of August 1932, involved an attempt to exonerate a young prisoner from corporal punishment. This prisoner had been punished during mandatory church service, a practice reviled by most inmates. The Protestant chapel was cramped, noisy, and unventilated. Attendees hated the Protestant chaplain, Reverend Smith, because “his attitude is always antagonistic … he seems to delight in preaching against thieves.”139 This intense loathing turned into sporadic heckling and booing. During the last Sunday service of August, as Behan told it, one inmate “gave voice to our thoughts: ‘B.S.’ Some officer picked out a man of the 400 men there and reported him. He went before the Warden, Mr. Smith, and received for punishment, although he pleaded not guilty, 10 strokes of the paddle, and 7 days bread and water. 7 days after, he was still marked black and blue.”140 In response, a deputation of ten men, including Behan, Garceau, Perrin, and Buck, chosen from different parts of the prison to represent each workshop, went before the warden as a group and pleaded for clemency, arguing that the young man was innocent. Though the deputation did not succeed, a similar effort was made on 7 September 1932, when another group, made up of eight men including Buck, Behan, Garceau, Cohen, Sydney Lass, and two men whose sentences expired before the riot, Kenneth Treapleten and Russel McKenzie, met Superintendent Ormond during his inspection visit and demanded, unsuccessfully, the release of John O’Brien from solitary confinement.141

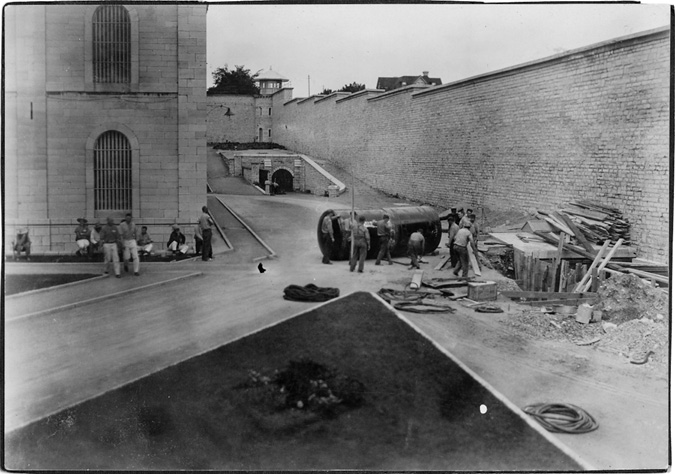

Trucks blockade the street fronting Kingston Penitentiary, 17 October 1932.

Courtesy of Jennifer McKendry.

Several noisy demonstrations, usually isolated to a single range or workshop, occurred throughout September and October. Two short-lived strikes took place in the #1 and #2 Stone Sheds during that period. Staff noted that the Stone Sheds were particularly difficult shops to manage: workers had been reported before for deliberately spoiling work and reading copies of manifestos openly at their work areas.142 Finally, a strike in Stone Shed #1 on 13 October 1932 brought matters to a head. A 25-year-old officer, guard William Boucher, was placed in charge of that gang. Inmates widely disliked Boucher. As inmate Edward Cada claimed, Boucher would “bother the boys when they were at their work. The men rose up over that.”143 The strike was organized by two men, Jean Dionne and John Saunders, who took the lead in passing around the plan and signalling its start by stopping work at a pre-arranged time and remaining silent and otherwise well behaved. The only demand of the 35 strikers was to speak to the deputy warden. Three inmates were democratically chosen as spokesmen and explained the situation to Deputy Warden Walsh when he arrived. Walsh responded by removing Boucher from the shop at noon, but Walsh returned later that afternoon and had the three spokesmen taken to solitary confinement. This step incensed the other prisoners in the shop, who felt that the punished men had not done anything to merit such treatment. Warden Smith wrote to Superintendent Ormond that day, reporting on the “spirit of unrest” in the penitentiary, and Ormond replied in frustration that allowing prisoners to force out a guard was a dangerous precedent.144

“I Know the Newspapers Call It a Riot, but It Was a Demonstration”: From Strike to Riot, 12 October to 17 October 1932

The 13 October strike became a cause célèbre in the prison. During the investigation, inmates mentioned Boucher and the punished spokesmen even if they had never met them. The 13 October strike appears to have accelerated organizing already underway for a larger strike, as Deputy Warden Walsh reported that he had known about the possibility of a protest as early as 1 October.145 Over the next few nights, inmates clandestinely organized a prison-wide strike, tapping out messages through water pipes and passing notes in Morse code. The prisoners set the date and time: 17 October at 3:00 p.m. At that time all workers would down tools and muster in the Shop Dome. On the morning of 17 October, several inmates warned individual officers that something was afoot. The prison administration made no organized response, however, and officers responsible for shop management were not briefed. At three o’clock, prisoners in every shop ceased work, gathered in groups to talk, and then left their workplaces. Several shops were locked up by their officers, despite inmate efforts to rush the doors, and these men escaped out the windows or waited to be released by other strikers. Some inmates ran from their workplaces to rally other shops to the strike, and key locations were secured, partly against the guards and partly to prevent younger “hotheads” from smashing up equipment and infrastructure like the power plant. Some armed themselves with their tools, hammers, wrenches, pieces of stone, bits of pipe, or scrap wood made into clubs, though these improvised weapons went unused during the strike.

The entire penitentiary became a struggle between supporters of the strike and the guards and prisoners unwilling or unable for whatever reason to join the strike. As the alarm bell rang, extramural labourers returned to the penitentiary. These outside workers refused to comply with orders to return to their cells until seeing other prisoners do so, and some men ran off to join the gathering in the Shop Dome.146 A group of inmates attempted to reach the Prison of Isolation but were driven back by rifle fire, and it is likely that this threat of violence made others hesitate and limited the spread of the strike. Willard Milich, working in the kitchen, armed himself with a butcher knife and convinced ten men to join “our little revolution.” He “cursed and swore and practically went wild and called [those who would not join him] yellow this and that” but was unable to force his way out, and a standoff ensued for the rest of the day.147 These same arguments played out in the cell blocks as well. As men were returned to their cells, the prisoners kept in the corridors interfered with the locking up. Using wooden planks negligently left in the surveillance galleries, they forced open the locking mechanisms and warded off a half-dozen unarmed officers. Inmates congregated and debated outside their cells for most of the afternoon and evening.148