Labour / Le Travail

Issue 89 (2022)

Presentation / Présentation

From the Royal Commission on the Status of Women to the National Action Committee

Introduction

Keywords: Royal Commission on the Status of Women, National Action Committee, Canadian feminism and Indigenous women, poverty, education, domestic labour, child care

Mots clefs : Commission royale d’enquête sur la situation de la femme au Canada, Comité canadien d’action sur le statut de la femme, féminisme canadien et femmes autochtones, pauvreté, éducation, travail domestique, garde d’enfants

The roundtable in this issue, “From the Royal Commission on the Status of Women to the National Action Committee,” marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (nac). In April of 1972, over 500 feminists met in Toronto for the “Strategy for Change” conference sponsored by the National Ad Hoc Committee on the Status of Women. Some Ad Hoc Committee organizers had been involved in the Committee for the Equality of Women (cew), which had demanded that Prime Minister Lester Pearson’s government appoint a royal commission to document women’s status and find ways to rectify gender inequality. Following the report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women (rcsw) in 1970, the Ad Hoc Committee resolved to hold the government’s feet to the fire, making sure that the report’s recommendations were implemented. The rcsw and nac were thus closely linked, though nac took on a life of its own, changing in organization, politics, methods, and outlook over time – a story told by other researchers.1 Because the rcsw and nac were connected, this roundtable addresses them together. Of course, given the political context of the early 1970s, an organization like nac might have evolved on its own. A resurgence of feminism on a global scale as well as within Canada, plus the proliferation of new varieties of feminism, led some activists to consider ways to foster a national conversation across the provincial, linguistic, and cultural boundaries that had often kept Canadian feminist organizing quite localized.

Historians have assessed both the rcsw’s and nac’s origins, meaning, impact, and legacy. In some writing, the rcsw is portrayed as a “watershed” for the women’s movement, supposedly initiating “second-wave feminism.”2 Skepticism about both the “three wave” model of feminism and the triggering prominence of this one event, however, suggests such claims are exaggerated. The rcsw did not singularly invent or resurrect feminism, but it did represent a transitional moment, and one that provided historians with a treasure trove of documents, archives, and media coverage that allows us to probe not only the economic and social context of gender, race, and class relations framing the rcsw, but also the public discussion that followed it.3 Indeed, the rcsw’s archival footprint itself is of interest: depending on which sources historians use – briefs, letters, media coverage, government documents – their conclusions can vary.4

Critiques of the rcsw appeared as soon as it issued its report, especially by radical and socialist feminists who rejected its embrace of male-defined success, its failure to address the structural basis of women’s oppression within capitalism, and its milquetoast recommendations.5 Even during rcsw hearings, Indigenous women and women of colour challenged the royal commission’s ability to comprehend their specific oppression.6 Reflections written in the 1990s by key rcsw players and some feminist reformers were more positive: commission head Florence Bird and research director Monique Bégin argued for its success as a necessarily pragmatic reform effort that “changed the course of social history.”7

Over time, scholars have provided a more complex balance sheet of the rcsw’s meaning and impact, including its limitations and insights, and its inherent and problematic assumptions, in relation to its recommendations, the commissioners’ politics, the federal bureaucracy, the social landscape, and political possibilities of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The rcsw’s failure to address gendered violence, its evasion of questions of sexuality, its lack of attention to immigration, and especially its colonial and racist assumptions of a “white” Canada have all been part of this conversation.

Similarly, nac too has been the subject of personal and historical reflection, though such writing has been less thorough than that concerned with the rcsw, in part because of nac’s much longer and far more complex existence.8 There is simply more to analyze; indeed, some topics remain tantalizingly open for question. The nac, unlike the rcsw, was an evolving, living organization that altered over time. Established as an autonomous, non-partisan entity with membership by affiliated organization (rather than individual), it initially focused on research, lobbying, and public education, developing a strategic but still limited “parliamentary activism.”9 However, it increasingly expanded its understanding of equality issues, moving away from the original focus on implementing the rcsw’s recommendations. Its politics and internal dynamic shifted over decades, shaped by the political culture, the economic context, other social movements, the unexpected in political life – and crucially, by the agency of nac activists themselves.

From the beginning, nac managed multiple feminisms under one roof, though it was consistently concerned with cementing ties with Québec feminists and engaging with Indigenous women. To optimists, nac’s pluralism was its strength: nac’s longevity, “ideological diversity and ability to bridge generations of feminists” were proof of a uniquely “Canadian” version of feminism.10 As Jill Vickers, Pauline Rankin, and Christine Appelle also argue, nac politics shifted considerably by the 1980s, as it encompassed broader equality goals and, pressed by leftist members, paid more attention to the needs of working-class women. More protest-oriented politics were grafted onto its lobbying role. If nac represented some ideological diversity, it did not initially embody racial diversity. Internal and external pressures forced nac to address the marginalization of women based on race and ethnicity, as well as sexual orientation and disability, within its own ranks and to rectify nac’s failure to develop antiracist perspectives and politics.11

This roundtable covers a few of the many themes that emerged in the rcsw and in the early nac. It is worth noting, in a labour studies journal, that the concept and experience of work were fundamental to both the rcsw and nac, even if their definitions of work entailed omissions and oversights, such as the rcsw’s inability to come to terms with women’s unpaid domestic labour, analyzed in this roundtable by Meg Luxton. Defined expansively, labour involved unpaid work, unemployment, motherwork, volunteer work, and of course paid labour, along with all the social institutions and issues that went with it, such as child care, family responsibilities, welfare, the tax system, education, and so on. Yet there is no doubt that paid labour often dominated its agenda, despite the rcsw’s stated purpose of validating women’s work in the home. This is not surprising, given the economic and social context. The rcsw emerged in a period when women’s labour force participation was shifting considerably, as more women, especially those with families, joined the workforce. This emerging, incremental change in where and how women laboured increasingly had radical implications for women’s consciousness, collective organizing, and interactions with political, economic, and social institutions.

Also, the impetus for the rcsw came in large part from women who were concerned with discrimination in the workforce, a resilient sexual division of labour, women’s lower pay, and lack of occupational choice. Although many were professional or white-collar workers, trade union and working-class women were represented on the Committee for the Equality of Women, also pushing for a royal commission. Work for pay was subsequently interpreted by the rcsw staff and commissioners as an important feminist issue – in contrast to their view that sexuality was a “private” concern.

However, the rcsw did not analyze women’s work within a class framework; it was firmly ensconced within a liberal feminist outlook, which meant the commission did not see the class structure (or capitalism) as inherently unequal, exploitative, or problematic. This, in turn, led to an implicit assumption that women could make a choice to labour within the home or (also) outside of it, when for working-class and racialized women, it was economic necessity, and not idealized free choice, that shaped their decisions. Nor did the rcsw explore the connections between motherwork and poverty, which, as Margaret Little argues here, was out of step with attention at the time, through the federal Croll Senate Committee on Poverty, to poverty issues. The rcsw also ignored the connection between work, ethnicity, and race. Whiteness was again taken for granted and the particular needs of immigrant women also accorded less visibility.

The growing numbers of unionized women, most especially in the public sector; the circulation of feminist ideas; the disjuncture women felt between the rhetoric of union equality and their actual second-class status; and especially the jarring juxtaposition between the reigning male breadwinner ideal and the reality of women’s essential breadwinning role all provided fertile ground for the growth of labour feminism revealed in rcsw hearings and briefs. Although the trade-union movement was incensed that no labour-movement person was appointed to the commission (unlike the similar Kennedy Commission on women in the United States), unions devoted considerable effort to their briefs and public presentations, some of which were quite forward thinking.

Since the earlier 1960s, some unionists had been collaborating with feminists in productive, if temporary, alliances; women in the United Auto Workers, for example, supported an Ontario liberal feminist lobby for legislation banning sex-based seniority and job advertising. Unions with a progressive leadership, such as the Canadian Union of Public Employees (cupe) – which notably had a feminist president, Grace Hartman, and a supportive research director, Gil Levine – became more vocal about gender equality. Reflecting a changing climate, in 1968 the Canadian Labour Congress finally added prohibitions against sex discrimination to its constitution.12

Paid labour was a recurring theme in rcsw briefs, internal research studies, women’s letters, and the commission’s final recommendations. Whether it was discussion of maternity leave, the sexual division of labour, unionization, lack of promotion, unequal pay, sexist work cultures, educational training, or reform of the federal civil service, the rcsw was interested in hearing from women in the paid labour force. There were some significant differences in women’s presentations; only unions, for example, emphasized collective bargaining as one of the most important routes to gender equality. Internal discussions within the house of labour, hidden from the press, could nonetheless be quite fraught. Within the labour movement, conflict between some labour feminists and male leaders simmered over what constituted a “labour” issue to be included in official briefs. Feminists in the Canadian Labour Congress committee working on their brief to the rcsw wanted abortion in; other leaders did not.13

Given the influence of the rcsw’s recommendations on the original nac, the ever-increasing numbers of women in the paid labour force, and the growing influence of labour feminism, paid labour was also central to the initial nac’s agenda. Again, this took in many issues such as pay equity, human rights protections, pensions, child care, the tax system, and later, immigration and free trade. While the rcsw could only make recommendations for new legislation covering the small percentage of workers under federal jurisdiction, nac had a much wider perspective and reach. In many cities and provinces, local “status of women” committees, tied loosely or firmly to nac, emerged, pursuing a more focused local agenda. In Ontario, for instance, the Ontario Committee on the Status of Women – founded in 1971 as a collaboration of liberal (and Liberal), social democratic, and union women – wrote to national corporations like Air Canada and the banks urging them to alter their sexist practices, but they also presented briefs to the Ontario government, pressed for pay equity, and supported strikes dominated by women workers at Dare, Fleck, and other workplaces.14 Across the country, similar “status of women” action committees took up workplace, legislative, and social issues of paid labour, as well as welfare reform, accessible and affordable child care, better human rights protections, and a multitude of other issues. Some sparked initiatives that reverberated across the movement for some time. Vancouver Status of Women, initially established as an effort to ensure implementation of the rcsw’s recommendations, began publishing a BC-based newspaper, Kinesis, in 1972. The publication evolved as an innovative avenue for feminist communication and debate, not only in British Columbia but beyond, covering a wide range of concerns including prison activism, domestic violence, wage labour, and colonialism – and far more. Like other new feminist newspapers, Kinesis also devoted considerable attention to uncovering the history of women’s varied labours – a topic previously marginalized not only in mainstream media and educational venues but also within the labour movement.

Even in its first decade, as nac tackled the rcsw’s recommendations, debates surfaced within its ranks, sometimes relayed in its newsletter, Status of Women; how pensions should be reconstructed to reflect women’s unpaid caring labour and less linear workforce participation was just one of many. The narrow agenda of how to implement the rcsw opened up questions of why certain policies were promoted and others not, as well as whose economic and social interests they favoured within the overgeneralized category of “women.”

Even as nac shifted course in the 1980s and 1990s, work-related issues remained central. Not only were union, labour, and socialist feminists determined to make nac a voice for working-class women, but antiracist feminists also knew that “work” – and indeed, class relations – could not be abstracted from the racism and xenophobia that women experienced. The issue of what a “feminist” concern was also re-emerged, not for nac but for the governments it lobbied. When nac waded into the free trade debate, arguing that capital would be the winners and working-class women the losers from free trade, Marjorie Cohen, a nac vice-president, remembers the reaction: as long as nac spoke to recognizable “women’s issues” such as daycare, its voices were accepted, but when it talked about the budget, privatization, or trade policy, “we were going too far.”15

These roundtable essays, marking the 50th anniversary of nac’s establishment, focus on the rcsw and the early years of nac. They are revealing precisely because they show how assumptions and weaknesses of the rcsw were translated, reproduced, and sometimes challenged in nac. Sarah Nickel’s essay shows a connection between the rcsw and nac but also a pivot into new territory as nac struggled to be an ally of Indigenous women. This was a complex endeavour, not the least because, as Nickel shows with some nuance, Indigenous women themselves were debating which political direction to take, especially vis-à-vis changing the “marrying out” clause of the Indian Act. Non-Indigenous feminists sought to overcome a shameful past of not addressing colonialism, though they sometimes could not shed colonialist attitudes.

As Meg Luxton’s contribution indicates, the rcsw’s liberal feminist framework and acceptance of capitalist social relations inhibited a full understanding of social reproduction. The rcsw rhetorically validated the economic contribution to society of housewives’ work but contradictorily remained wedded to the ideal of a privatized, nuclear family household, leading to the commission’s inability to create policy alternatives that might truly address the inequities of both paid and unpaid labour – and this only worsened in increasingly neoliberal times.

The rcsw’s idealized notion of choice about waged work that Luxton critiques is echoed in Lisa Pasolli’s discussion of child care. Pasolli also directs our attention to the importance of tax policy in the rcsw’s approach to child care. Because much political attention was focused on feminists’ subsequent demand for state-funded universal child care, we can forget that many presentations to the rcsw called for a tax solution, specifically, a tax deduction for women using child care. The commission’s report called for an overhaul of tax policies as one crucial instrument, among others, to aid working women needing child care, though the government ignored these recommendations, instead adopting a childcare tax deduction that the rcsw had not endorsed because it recognized that this measure would favour more affluent women workers.

The liberal feminist outlook of the commission meant education was a very significant concern for the commissioners and for many individuals and organizations that made presentations or contributed briefs. As Rebecca Coulter shows, improving institutional education was seen as a critical means of preparing women for better, and equal, opportunity in the labour market, and even those feminists disappointed with the commission’s liberal orientation saw the rcsw as a “strategic opportunity” to press debates about education and work in new directions. Coulter concludes with an important point: pedagogy meant far more than educational policy or institutions, as the women’s movement itself became a force of feminist, transformative pedagogy.

Finally, Margaret Little’s piece brings our attention back to the rcsw’s inordinate focus on improving women’s lives in the world of paid work and its surprising silence about women’s poverty, despite receiving a few presentations containing both policy and experiential material from sole-support parents. In the commission’s report, there was a lacuna of recommendations addressing poverty, such as the guaranteed annual income, a concept circulating at the time and certainly discussed in relation to the contemporaneous Croll hearings. Little also looks at the briefs of ethnic and racialized organizations, noting that Indigenous women recognized poverty as a critical issue of concern. Connecting the rcsw and nac, Little contends that the latter’s antipathy to groups like Wages for Housework reflected an ongoing inability of many feminists of different political views to listen to the demands of single mothers’ antipoverty groups.

These five pieces are snapshots, rather than a comprehensive picture, of this topic, and most especially of nac. More research, grounded in multiple methodologies, including an exploration of the extensive primary sources that are increasingly available in archives, is needed. All of these contributions remind us that the history of feminist organizing in the later 20th century is an ongoing, rather than a settled, question – one that needs to take into account the interplay between changing material, social, and ideological contexts and the ideas, strategies, and actions of the multiple, varied feminist efforts that made up the women’s movement.

1. A few examples include Jill Vickers, Pauline Rankin and Christine Appelle, Politics as If Women Mattered: A Political Analysis of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993); Caroline Andrew and Sanda Rodgers, eds., Women and the Canadian State (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997); Mary Jo Nadeau, “The Making and Unmaking of a ‘Parliament of Women’: Nation, Race and the Politics of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, 1972–1992,” PhD thesis, York University, 2005; Nancy Worsfold, “An Organization and Its Discontents: The National Action Committee on the Status of Women,” ma thesis, Concordia University, 1990; Lynne Marks, Margaret Little, Megan Gaucher and T. R. Noddings, “‘A Job That Should Be Respected’: Contested Visions of Motherhood and English Canada’s Second Wave Women’s Movements, 1970–1990,” Women’s History Review 25, 5 (2016): 771–790; Jessica Weiser, “Ruling Relations and Representations: The Toronto Star’s Depiction of nac, 1983–1997,” ma thesis, oise, 1998.

2. Freda Paltiel, “State Initiatives: Impetus and Effects,” in Andrew and Rodgers, eds., Women and the Canadian State, 27.

3. Cerise Morris, “No More than Simple Justice: The Royal Commission on the Status of Women and Social Change in Canada,” PhD thesis, McGill University, 1982; Jane Arscott, “‘More Explosive Than Any Terrorist’s Time Bomb’: The rcsw, Then and Now,” paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montréal, 2 June 2010; Arscott, “Twenty-Five Years and Sixty-Five Minutes after the Royal Commission on the Status of Women,” International Journal of Canadian Studies 11 (Spring 1995): 30–56; Kimberly Speers, “The Royal Commission on the Status of Women: A Study of the Contradictions and Limitations of Liberal Feminism,” ma thesis, Queen’s University, 1994; Kathryn McLeod, “Laying the Foundation: The Women’s Bureau, the Royal Commission on the Status of Women and Canadian Feminism,” ma thesis, Laurentian University, 2006. See also many of the essays in Andrew and Rodgers, eds., Women and the Canadian State.

4. Annis May Timpson, “Royal Commissions as Sites of Resistance: Women’s Challenges on Child Care in the Royal Commission on the Status of Women,” International Journal of Canadian Studies 20 (Fall 1999): 1–24; Joan Sangster, “Women’s Experience as Evidence: Letters to the Royal Commission on the Status of Women,” in Through Feminist Eyes: Essays on Canadian Women’s History (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2011), 359–90; Barbara Freeman, The Satellite Sex: The Media and Women’s Issues in English Canada, 1966–1971 (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2001); Shannon Stettner, “‘He Is Still Unwanted’: Women’s Assertions of Authority over Abortion in Letters to the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 29, 1 (2012): 151–171.

5. Newspaper clippings, Royal Commission on the Status of Women fonds, rg33-89 (hereafter rcsw), vol. 44, Library and Archives Canada (lac). See also “Pie in the Sky,” in Women Unite! An Anthology of the Canadian Women’s Movement (Toronto: Canadian Women’s Educational Press, 1972), 40–42; Pat Armstrong and Hugh Armstrong, The Double Ghetto: Canadian Women and Their Segregated Work (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1984), 135–140; Pat Marchak, “A Critical Review of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women Report,” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 9, 1 (1972): 73–96.

6. Carrie Best quoted in Victoria Province, 17 April 1968, and Pictou Advocate, 18 September 1968; Newspaper clippings, rcsw, vol. 41, lac; Mary Anne Lahache, rcsw, vol. 17, brief 394, rcsw, lac. On the rcsw in the North, including northern Indigenous women answering back to colonial views, see Joan Sangster, The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2016), 223–273.

7. Monique Bégin quoted in Joan Sangster, Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Post-war Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 236. See also Monique Bégin, “The Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada: Twenty Years Later,” in Constance Backhouse and David H. Flaherty, eds., Challenging Times: The Women’s Movement in Canada and the United States (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992), 21–38; Bégin, Ladies, Upstairs! My Life in Politics and After (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018); Florence Bird, Anne Francis: An Autobiography (Toronto: Clarke Irwin, 1974). There are also articles on specific issues the rcsw raised: for example, Lorna Marsden, “The Role of the National Action Committee in Facilitating Equal Pay Policy in Canada,” in Ronnie Steinberg Ratner, ed., Equal Employment Policy for Women (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), 242–260.

8. For just two interviews/reflections, see “Interview with Judy Rebick,” Studies in Political Economy 44, 1 (1994): 39–71; “Sunera Thobani: A Very Public Intellectual,” interview by William K. Carroll, Socialist Studies/Études socialistes 8, 2 (2012): 12–30.

9. Nadeau, “Making and Unmaking.”

10. Vickers, Rankin and Appelle, Politics.

11. Vijay Agnew, Resisting Discrimination: Women from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean and the Women’s Movement in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996).

12. Pamela Sugiman, “Unionism and Feminism in the Canadian Auto Workers Union, 1961–1992,” in Linda Briskin and Patricia McDermott, eds., Women Challenging Unions: Feminism, Democracy, and Militancy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 172–190; Susan Crean, Grace Hartman: A Woman for Her Time (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1995); Meg Luxton, “Feminism as a Class Act: Working-Class Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 48 (Fall 2001): 63–88.

13. On the rcsw and the labour movement, see Joan Sangster, “Tackling the ‘Problem’ of the Woman Worker: The Labour Movement, Working Women and the Royal Commission on the Status of Women,” in Transforming Labour, 233–268.

14. Beth Atcheson and Lorna Marsden, eds., White Gloves Off: The Work of the Ontario Committee on the Status of Women (Toronto: Second Story Press, 2018).

15. Marjorie Griffin Cohen, “The Canadian Women’s Movement and Its Efforts to Influence the Canadian Economy,” in Backhouse and Flaherty, eds., Challenging Times, 218; Cohen, Free Trade and the Future of Women’s Work: Manufacturing and Service Industries (Toronto: Garamond, 1987). See also Sylvia Bashevkin, “Free Trade and Canadian Feminism: The Case of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women,” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de Politiques 15, 4 (1989): 363–375.

“We Now Must Take Action”: Indigenous Women, Activism, and the Aftermath of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women

In 1980, Kanien’kehá:ka woman Mary Two-Axe Earley rose to address delegates at the annual meeting of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (nac). Prefacing her comments by confirming that Canada was a great place to live, she nonetheless highlighted the sexism and racism that Indigenous women experienced:

We Indian women stand before you as the least members of your society. You may ask yourself why? First, we are excluded from the protection of the Canadian Bill of Rights or the intercessions of any Human Rights Commission as the Indian Act supersedes the laws governing the majority. Second, we are subject to a law wherein the only equality is the inequality of treatment of both status and non status women. Third, we are subject to the punitive actions of dictatorial chiefs half-crazed with newly acquired powers recently bestowed by a government concerned with their self-determination. Fourth, we are stripped naked of any legal protection and raped by those who would take advantage of the inequities afforded by the Indian Act.1

Continuing, Two-Axe Earley explained that section 12(1)(b) of the Indian Act prevented First Nations women from being buried beside their mothers and fathers on-reserve if they had married outside of their communities. These women were also subject to eviction and expulsion from tribal roles, forfeited inheritances and property, and were divested from the right to vote in band elections. Chiefs “steeped in chauvinistic patriarchy” ruled them, she argued, and these women were unable to pass their “indianness and Indian culture by mother to her children.”2 Two-Axe Earley made clear that the sexism codified in the Indian Act and internalized in Indigenous community leadership needed to be eliminated.

This presentation to the nac was not her first. Two-Axe Earley had been involved in this volunteer organization since its inception – in 1972, in the aftermath of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women (rcsw), to coordinate member groups in the bid for women’s quality.3 And earlier, in 1968, she gave a similar address to the rcsw with the support of a delegation of 30 Kanien’kehá:ka women from both sides of the Canada-US border, when she was just beginning Equal Rights for Equal Women – the Indigenous women’s organization that would become synonymous with the status issue (and a precursor to Indian Rights for Indian Women).4 Along with Two-Axe Earley, Indigenous women across Canada were taking up the opportunity to advocate for their rights in new feminist forums, and they would not back down.

Exploring Indigenous women’s activism through organizational records and reports from Indigenous women’s organizations, the rcsw, and the nac provides critical insight not only into how Indigenous women understood their own marginalization in terms of race, gender, and class but also into how others around them, including allies in the mainstream women’s movement, supported them and helped advocate for change. Drawing from these sources, I demonstrate how participation in and outcomes of Indigenous women’s activism in other feminist circles could be uneven, such as when the rcsw failed to explicitly address colonialism as a key factor in Indigenous women’s experiences and did not account for Indigenous women’s existing political work in their own organizations. The nac, too, could flatten Indigenous women’s broader political concerns into the singular issue of status under the Indian Act, which undermined the depth and breadth of women’s struggles. But women also learned from one another and worked within the channels available to them as best they could. Indigenous women were vocal about what they needed, and non-Indigenous women listened and used their networks to amplify Indigenous women’s voices. In some cases, non-Indigenous women were dedicated allies who could bear the brunt of advocacy work, allowing Indigenous women to direct their efforts elsewhere and to continue to grow their independent political movement. The complexity of women’s interactions, relationships, and political mobilizations is critical to better understanding feminist action during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Indigenous Women and the Royal Commission on the Status of Women

Indigenous women’s involvement in feminist organizing around the rcsw appears almost negligible at first glance. There were no throngs of Indigenous women sending letters and briefs en masse to the rcsw, nor were there hordes of women intent on giving testimony at public hearings. But Indigenous women were present and, in many cases, simply built their participation in the commission onto their existing and ongoing political work. In addition to Two-Axe Earley, representatives of groups and organizations that took part in the rcsw in 1967 and 1968 included Mary Ann Lavallée (a driving force in the creation of the Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association) and Alice Steinhauer, June Stifle (Maria Campbell), and Christine Daniels (on behalf of the Alberta Native Women’s Conference, which initiated the Voice of Alberta Native Women’s Society).5 These women participated just as their organizations were developing to create space for their political work.

In fact, in November 1967, Lavallée helped organize a conference in Saskatoon for 60 delegates from a group calling itself the Saskatchewan Indian Women. The women who attended discussed poor living conditions for their children, and, responding to high rates of child apprehensions, they recommended shifting the jurisdiction of child welfare from the federal government to the provinces.6 Recognizing the need to pressure for changes through a formal organization, the women created the Indian Women of Saskatchewan, a precursor to the Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association (siwa).7 This was a key political moment for Saskatchewan women, but it also built critical capacity across the West, as several delegates from outside Saskatchewan attended the conference including Steinhauer, Daniels, and Mary Ruth McDougall, who launched their own Alberta conference the next year based on the Saskatchewan meeting.

This First Alberta Native Women’s Conference would draw women to Edmonton from across Canada, including Lavallée, who, in her keynote address, referenced the upcoming rcsw and some of the concerns “white women” were presenting. She suggested that “by the end of this conference we should come up with some suggestions and resolutions that will benefit Indian woman and her everyday world.”8 The meeting, held just a month before the royal commission began its hearings, attracted over 300 delegates to Edmonton, and while organizers admitted not knowing much about the rcsw, they agreed it would be useful to take their conference resolutions to it. So they did.

The resulting rcsw submission demanded better housing and sanitation services, Indigenous control over child welfare services, the extension of medical services into isolated areas, and cultural training for teachers, to provide less racially biased education.9 The group also highlighted the discrimination and criminalization of young Indigenous women moving into urban areas, leading it to suggest (and the rcsw to ultimately recommend) establishing halfway houses in the cities to provide short-term housing and guidance on employment possibilities, city services, and educational opportunities.10 And while the women were open to considering the commission as an audience for their work, they were also thinking beyond it to other political avenues.

Not only did the First Alberta Native Women’s Conference lead to the creation of the Voice of Alberta Native Women’s Society (vanws), which advocated for women’s and children’s rights for the next two decades, but the group also presented its resolutions to Premier Ernest Manning and to the April 1968 Indian Association of Alberta conference.11 Indigenous women knew to cast their nets wide to see results, and they were not pinning their hopes only on the royal commission (which, as mentioned, they were not familiar with) or the male-dominated Indigenous organizations (which often excluded them). Instead, they prioritized meeting together in large conferences to identify problems, strategize feasible solutions, and then seek whatever outside support they might need.

Still, the resulting report of the rcsw was disappointing in that Indigenous women’s concerns were subsumed within wider thematic sections largely concerned with non-Indigenous women. Joan Sangster has argued that the commission was genuinely concerned about the marginalization of Indigenous women and had ongoing conversations about how best to ensure their representation and inclusion in the process, but some of the commissioners’ actions could be flawed. This was the case when the commission enlisted the rcmp to track an Indigenous woman down who had submitted a letter but was not planning to attend the hearing in Yellowknife.12 Here, and elsewhere, the commission reproduced rather than challenged settler-colonial dynamics.

Indeed, Benita Bunjun insisted that the rcsw is a “colonial archive” that “furthered nation-building projects while crystallising Indigenous women and women of color as the Other … reproduc[ing] nation-building discourses of essentialism, racialization, and exclusion.”13 This was similar to Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond’s 20th-anniversary assessment of the commission, which she labelled “patriarchy and paternalism,” noting that the entire premise of the commission – what she branded “equal opportunities for women” – was culturally and conceptually inappropriate for Indigenous women.14 Barbara Freeman also noted sexist and racist media coverage of Indigenous women’s involvement in the commission, including by cbc reporters who portrayed many as naïve; in one case, cbc reporter Ed Reid covered Lavallée’s presentation and praised her competency as if it was some sort of shock.15 These scholars also stressed the exclusion, misrepresentation, and essentializing of Indigenous women’s needs and realities – particularly the ways in which white settler women talked “about” Indigenous women’s needs solely in terms of education and poverty without reference to colonial realities.16

Afterwards

Nevertheless, Sangster and others have noted that Indigenous women carved out spaces to “answer back” to the stereotypes and misrepresentations of them held by commissioners and participants alike, and that this “answering back took on more assertive public forms in the 1970s.”17 This was certainly the case with vanws president Bertha Clark’s 1971 letter to Robert Stanbury, Parliamentary Secretary to the Secretary of State, in which Clark insisted that “the recently published report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women of Canada provides an opportunity for Native, Indian and Eskimo women to give their opinions and expressions on the development of the role of women in Canada. Our grandmothers have paved a great role in their early struggle for a way of life. We now must take action to maintain this way.”18 For Clark and others, this was a critical juncture in the Indigenous women’s movement, with several Indigenous women’s organizations emerging, and the rcsw provided a key opening for their voices to be heard.

In the aftermath of the rcsw, Indigenous women looked both inward and outward to seek solutions, much as they had during the commission. They tended to their own budding provincial organizations to pursue immediate action on the most pressing issues in their communities, outlined in their briefs and presentations, but by the early 1970s, just as the nac formed, the Indigenous women’s movement too was shifting toward building a national organization. To facilitate this, women held two important national conferences: the first hosted by vanws in Edmonton in 1971, and the second the following year in Saskatoon, where two bodies emerged – the National Steering Committee for Native Women and the National Committee for Indian Rights for Indian Women (iriw).19 These meetings confirmed that most Indigenous women favoured coming together to secure political recognition and better conditions for their communities, but they disagreed on vital issues such as women’s status under the Indian Act and what a permanent national forum would look like, and this would frame their activism throughout the 1970s.20

For instance, at the Saskatoon conference, siwa president Lavallée refused to recognize iriw as a legally organized body capable of facilitating changes to Indian Act membership rights, insisting that only bands had the authority to address band membership. She likewise challenged the rcsw’s recommendations to allow women and their children to retain status on marrying out, demanding the “offending paragraph be stricken from the records of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women.” For Lavallée and her supporters, “this recommendation was presented to the Commission by persons without the express authority of the Indian Women of Saskatchewan,” and they did not “in any way, shape, or form, [give] our consent to anyone to present a resolution, petition, or directive to the Royal Commission.”21 But not everyone shared Lavallée’s sentiment. The diversity of the Indigenous women’s movement was both a strength and a liability, and it certainly framed the movement’s engagements with the nac in the following years.22

Coalition Building: National Action Committee on the Status of Women

By 1973, when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against Jeannette Lavell’s bid to have her status reinstated, the two national bodies and several provincial associations were nac members; together, iriw, the Steering Committee, and the nac hosted a national demonstration to mourn the death of the Canadian Bill of Rights in response to the disappointing Lavell decision.23 The main demonstration, held in front of the Pacific Centre building in Vancouver on 22 October 1973, was well attended, demonstrating the growing strength of feminist coalition building and the nac’s willingness to publicize its position on Indian status issues.24 Over the next few years, provincial Indigenous women’s organizations continued to join the nac as official members and to participate in meetings with the advisory council.

Nationally, iriw continued actively working with the nac on the status issue, pressing for change wherever possible. In spring 1977, a Senate Committee was considering the Canadian Human Rights Act (Bill C-25), which would make discrimination based on sex unlawful, but it did not have Indigenous women’s unique legal relationship to sexism within its purview – that is, until the nac pressured the Senate Committee to also consider First Nations women’s sex discrimination under the Indian Act as part of its deliberations.25 Meanwhile, in March iriw representatives Jenny Margetts and Mary Two-Axe Earley addressed members of the House of Commons demanding the removal of section 12(1)(b) from the Indian Act.26 Both women’s groups were particularly incensed that the federal government chose to consult with the mostly male National Indian Brotherhood when revising the Indian Act, but women’s organizations and, more importantly, enfranchised Indigenous women were not included in these discussions.27 Together the nac and iriw wrote to the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to demand women’s involvement, and by the summer of 1977, bolstered by this collective work, the groups announced a three-year joint research project to study status discrimination.28

Mary Two-Axe Earley and Jenny Margetts at a nac meeting, March 1977.

10-024-S11-F2-I6, Canadian Women’s Movement Archives, University of Ottawa.

Progress was slow, however, particularly in the face of government resistance to women’s advocacy. In 1976 and 1977, Indian Affairs ministers Judd Buchanan and Warren Allmand censured the nac for its stance on Indian status. In their lengthy, patronizing, and, in places, identical letters to nac president Lorna Marsden and nac secretary Brigid Munsche, Buchanan and Allmand insisted that nac members – and, by extension, Indigenous women – did not fully understand the law around Indian status and lands reserved for Indians, so they cited the same sections of the Indian Act, explaining the process for women’s status loss.29 Insisting to Marsden and Munsche that they too shared concerns about women’s status, Buchanan and Allmand ignorantly assured the women they had nothing to fear, as the Department of Indian Affairs was consulting with the National Indian Brotherhood about Indian Act changes.30 In many ways, the paternalism within these responses struck at the heart of what was wrong with Canadian Indian policy and those who upheld it. It failed to account for women’s perspectives and experiences and placed decision-making firmly in the hands of Indigenous and non-Indigenous men. The nac’s dedication to this cause caught the attention of Two-Axe Earley, who insisted Marsden’s letters to the prime minister and the ministers of Indian and Northern Affairs (which had precipitated Buchanan’s response) “were just fantastic,” and she was grateful to Marsden for writing on Indigenous women’s behalf.31

By April 1982, despite consistent efforts including letter-writing campaigns and meetings with government ministers, little had changed, and Indigenous women and their allies donned black armbands and once again took to the streets in demonstrations of mourning in Ottawa, Toronto, Edmonton, and Vancouver regarding the yet-unresolved status issue. A nac press release highlighted women’s collective frustration: “It has been 14 years since the issue of equal rights for Indian women was raised in the report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women.” Calling on government to repeal the offending Indian Act section, the group insisted that “Indian women are discouraged and angered by the empty promises and the facade of equal rights for women and men in Canada.”32 Of course, Indigenous women’s experiences with legislated gender inequality stretched back much further; still, highlighting the number of years that had passed since the rcsw also demonstrated a long and growing partnership between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women, at least in public.

Challenging the nac

Despite outward appearances of feminist solidarity, Indigenous women’s relationship to the nac was not without challenges, and, in part, this was owing to the diversity of the Indigenous women’s movement itself. Many organizations joined the nac as official members, kept in communication, and expressed appreciation for the nac’s efforts.33 But there were detractors, too, including Native Women’s Association of Canada (nwac) president Marlene Pierre-Aggamaway, who in late May 1981 criticized the nac’s “single-minded approach” when it came to Indigenous women. Prefacing her concerns about the nac’s plan to “develop a campaign to aid the fight of Native women in removing discrimination against them, as legislated in the Indian Act” with the reminder that nwac “works on behalf of all Native women regardless of their government imposed status or where they live,” Pierre-Aggamaway explained that nwac’s concerns were broad. She continued, pointing out that “many non-Native women viewed the problems and concerns of Native women as being directly related to section 12 (1) (b) of the Indian Act, and conversely, that the removal of that clause would remove all discrimination.” She disagreed, noting that this would simply be one solution of many needed to adequately address Indigenous women’s marginalization.34

Beyond an innocuous correction, Pierre-Aggamaway maintained that “because of the differing opinions about emphasis and solution, we have found our interaction with non-native women’s groups frustrating, and to be quite frank, of little support to the activities engaged in by our membership at the community level.” What this meant was that the broad efforts of the nac (and by extension, iriw) to support Indigenous women was missing the mark in terms of meaningful engagement, at least for Pierre-Aggamaway. She did not dispute the important “leadership role” iriw provided for the status issue but felt the only real solution to gender inequality was Indigenous sovereignty. In the meantime, she insisted, the nwac would focus on short-term solutions to address community needs in the form of “transition houses, daycare centres, employment counselling, crisis intervention, and health and lifeskills education.”35

Unpacking Pierre-Aggamaway’s critique requires us to understand the multiplicity and autonomy of the Indigenous women’s movement, whereby organizations followed mandates determined by their own delegates – mandates that did not always align with those of other associations. It is also unclear what the broader context of her criticism is: if it is grounded in frustration with the Indigenous women’s political movement or the nac as an organization. But given her role as president of the only other national Indigenous women’s organization, it is worth exploring her appraisal.

In some respects, this criticism was warranted. In surveying the National Action Committee on the Status of Women fonds at the University of Ottawa Archives and Special Collections, outgoing correspondence from the nac office is dominated by advocacy around the Indian Act, largely related to garnering publicity and support from government ministers, senators, the Canadian Human Rights Commission, and other sympathetic organizations to repeal the offending section. Correspondence ranges from form letters sent out en masse to government ministers, which lack detail but call for changes to the Indian Act, to impassioned letters highlighting individual cases of women and children being evicted from their homes by band councils.36 Records also detail the nac’s demonstrations around the status issue and participation in a joint research project with iriw. The nac additionally passed a resolution at its 1976 annual meeting calling for the Bill of Rights to apply to Native women and forwarded materials about Indigenous women’s legal discrimination to Amnesty International, which had been criticized for “not tak[ing] much action as regards rights of Indigenous people.”37

Yet, the nac also made interventions on behalf of Indigenous women in other areas – such as lobbying for organizations like iriw to be better funded, since it received marginal funding in comparison with Indigenous men’s organizations and in a May 1976 letter to Prime Minister Trudeau, the organization positioned itself wholly in favour of Indigenous women in the movement to patriate the constitution.38 For these issues, the nac placed itself in direct conflict with the male-dominated Indigenous Rights movement, which proved largely unconcerned with gender inequality. And this was no small thing. Through the late 1970s, the nac was also increasingly concerned about Indigenous child welfare, passing a resolution to pressure governments for Indigenous children to be placed in Indigenous homes rather than in non-Indigenous foster homes, by providing foster-parent funding for relatives to support the children.39 In these instances, the nac provided important support for issues that Indigenous women’s organizations prioritized and agreed upon.

It is also important to remember that the nac advocated for issues deemed appropriate by at least some Indigenous women, and iriw’s key role with the nac meant that it followed the status question. But it was also deeply concerned about satisfying the two national Indigenous women’s organizations, with president Jean Wood noting that if the nac failed to do this, it would be difficult to attract other Indigenous women’s groups. Thus, Pierre-Aggamaway’s critiques were significant.40 In fact, just a few weeks prior to receiving Pierre-Aggamaway’s letter, Wood spoke with nac executive member Caroline Ennis (who was also a noted Tobique activist) to develop a plan with iriw (and nwac if it was amenable) for improving the status of Indigenous women, and even offered $5,000 donations to each organization despite the nac’s own limited funding.41 Central to their correspondence is Wood’s anxious assertion that the nac needed to engage with iriw and nwac about any advocacy plans before they went forward. Wood and others, then, were already aware of the tenuous terrain they were operating on, and they did their best to be good allies.

Conclusion

This brief investigation into Indigenous women’s participation in the rcsw and the nac makes clear the need for nuance when examining women’s movements to ensure women are not siloed into separate arenas when in fact their work and experiences were often overlapping and mutually informing. It follows Sangster’s examination of 100 years of Canadian feminism and Lara Campbell’s A Great Revolutionary Wave: Women and the Vote in British Columbia, which are just two of the most recent examples of what is possible when we soften the edges of movements to see how women moved out of their respective groups to engage with others.42 Indeed, Indigenous women inserted themselves in the rcsw and the nac when and where it made sense to them, but they integrated their involvement with these organizations into their increasingly formalized activism and did not always agree on which issues to take up and how to mobilize with non-Indigenous women.

Indigenous child welfare issues, for instance, garnered significant agreement and co-operation among Indigenous women who had witnessed the devastating effects of high rates of child apprehensions in their communities. They were united in addressing this through several interrelated efforts, including creating more Indigenous foster homes, seeking administrative control over child welfare, opening shelters and daycares to prevent apprehensions, and pressing governments to provide better financial support to families. Where there was less agreement was on the Indian Act status issue, as many feared the impact that reinstated status might have in terms of not only material resources in communities but also family and community dynamics. And yet, despite the division and diversity across the Indigenous women’s movement, women understood the benefit of uniting within national organizations such as nwac and iriw to ensure their voices were heard at a national level. They had learned that it was all too easy for government officials to ignore calls from local and regional organizations and that by combining their efforts, they would see greater results.

The non-Indigenous women’s movement was likewise diverse and evolving, with members holding multiple positionalities and political views that shaped the ways they engaged with Indigenous women in the rcsw and the nac. Many were deeply influenced by the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, including the Red Power movement, which opened their eyes to racial injustice in addition to gender oppression, and this is visible (if imperfect) within the rcsw. Organized efforts shifted with this awareness, and we can see how the nac, for instance, became less of a benign pressure group and more protest oriented throughout the 1970s and 1980s. And while it was not always possible for non-Indigenous women to escape their own positionalities and internalized colonialism, they were genuine and thoughtful in their engagement with their peers and united in their efforts to press for Indigenous women’s rights.

Thank you to Joan Sangster for inviting me to take part in this roundtable and for providing insightful comments. Connor Thompson, Tyla Betke, and Courtney Bowman provided excellent research assistance for this work, and this research was made possible by financial support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

1. “Mary Two-Axe Earley speaks to the nac annual meeting,” 1980, Indigenous Women Reports and Correspondence, 1979–82, Equal Rights for Indian Women, National Action Committee on the Status of Women fonds (hereafter nac fonds), box 81, file 6, Canadian Women’s Movement Archives, University of Ottawa (hereafter cwma).

2. “Mary Two-Axe Earley speaks.”

3. “National Action Committee on the Status of Women (nac)/Comité canadien d’action sur le statut de la femme (cca),” n.d., Rise Up! A Digital Archive of Feminist Activism, accessed 12 November 2021, https://riseupfeministarchive.ca/activism/organizations/national-action-committee-on-the-status-of-women-nac/.

4. Indian Rights for Indian Women did not supersede Equal Rights for Indian Women. The latter organization, which Two-Axe Earley also took part in, was national, but she often continued to refer to the original organization as well.

5. Individual Indigenous women also took part in the rcsw, writing briefs and providing testimony about their personal experiences with racial and gender-based discrimination. Together, representatives from status and non-status First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities were united in calling out systemic barriers to education, inadequate living conditions, improper health care, lack of self-government, and, for First Nations, unequal legal status through sexist Indian Act provisions.

6. The Indian Women of Saskatchewan, Mrs. Rose Ewack, and Mrs. Mary Ann Lavallée to the Honorable Cy McDonald, Minister of Welfare for Saskatchewan, and the Honorable Arthur Laing, Minister of Northern and Indian Affairs, 14 November 1967, Regina Voice of Women (vow) fonds, Brief to the Saskatchewan Government by the Indian Women’s Conference, 1967–68, R-138, file VI.4, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan (hereafter pas).

7. Indian Women of Saskatchewan, Ewack, and Lavallée to McDonald and Laing, pas; Marjory Mulvagh, Secretary, House of Commons, Office of the Leader of the Opposition, to Irene Blewett, Secretary, Regina Voice of Women, 16 April 1968, Regina vow fonds, Brief to the Saskatchewan Government by the Indian Women’s Conference, 1967–68, R-138, file VI.4, pas; fsi Annual Conference, News for Saskatchewan Indian Women, October 1969, Muriel J. Clipsham fonds, Saskatchewan Indian Women, 1969–70, R-298, file 14.b, pas.

8. Mary Ann Lavallée, “The Role of Native Women – Past, Present, and Future,” paper presented at the Alberta Native Women’s Conference, Edmonton, 12–15 March 1968, pr1999.0465, file 78, Provincial Archives of Alberta (hereafter paa).

9. Canada, Royal Commission on the Status of Women (rcsw) – Submission, brief submitted by Alberta Native Women’s Conference (Edmonton), brief 310, vol. 15, rg33/89, lac; Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada (Ottawa 1970), 330–331.

10. Canada, rcsw – Submission, brief 310; Canada, Report, 330–331; Canada, rcsw, Precis of Public Hearings, Edmonton, 26 April 1968, Alberta Native Women’s Conference, Spokesmen, Mrs. Donils [Daniels], Mrs. Steinhowser [Steinhauser], Mrs. Stiple [Stifle], brief 310, vol. 10, exhibit 74, rg33/89, lac; Alberta Native Women’s Conference, 12–15 March 1968, Recommendations, Conferences and Training Courses, 1967–68, gr1979.0152, box 8, file 0084, paa.

11. Alberta Native Women’s Conference, Recommendations, paa; “Brief to Manning: Natives Protest Meddling” (editorial), Lethbridge Herald, 16 March 1968.

12. Joan Sangster, The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2016), 229.

13. Benita Bunjun, “The Making of a Colonial Archive: The Royal Commission on the Status of Women,” Education as Change 22, 2 (2018): 1.

14. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, “Patriarchy and Paternalism: The Legacy of the Canadian State for First Nations Women,” in Caroline Andrew and Sanda Rodgers, eds., Women and the Canadian State (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997), 175.

15. Barbara Freeman, “Same/Difference: The Media, Equal Rights and Aboriginal Women in Canada, 1968,” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 18, 1 (1998): 99–100.

16. Bunjun, “Colonial Archive,” 8.

17. Sangster, Iconic North, 225.

18. Bertha Clark, President, Voice of Alberta Native Women’s Society, to the Honourable Robert Stanbury, Department of the Secretary of State, 8 January 1971, Canadian organizations – Alberta Native Women’s Society, 1968/07–1972/07, rg6-f-4, box 95, 1986-87/319 gad, lac.

19. Members of the temporary National Steering Committee for Native Women consisted of representatives from provincial and territorial organizations who attended the First Native Women’s Conference in Edmonton. It was chaired by Jean Goodwill and signing officers included Irene Tootoosis, president of the Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association, and Elizabeth Paul, conference coordinator. The committee eventually led to the formation of the second national Indigenous women’s organization, the Native Women’s Association of Canada. National Steering Committee for Native Women, grant application form, Secretary of State, Citizenship Branch, n.d., Canadian Organizations – National Steering Committee of Native Women, 1986-87/319 gad, rg6-f-4, box 96, file 10, lac; Monica Turner, Member of National Steering Committee for Native Women, to James McGuire, Thunder Bay, 26 January 1972, Indians – Women – General, 1986-87/319 gad, rf6-f-4, box 12, file 2, lac. iriw was incorporated in 1971 and nwac in 1974.

20. C. Keeper, “Grant Recommendation,” memorandum to Minister of State, 17 November 1971, Canadian Organizations – National Steering Committee of Native Women 1986-87/319 gad, rg6-f-4, box 96, file 10, lac; “The List,” Bulletin: Canadian Association in Support of the Native Peoples: An Independent Journal on Native Affairs 18, 4 (1978): 44–45.

21. Mary Anne Lavallée, address to the National Native Women’s Conference, Hotel Bessborough, Saskatoon, 23 March 1972, Canadian Organizations – Indian Women of Sask [Saskatchewan], 1971/10–1972/08, 1986-87/319 gad, rg6-f-4, box 97, lac.

22. “Indian Rights for Indian Women,” Bulletin: Canadian Association in Support of the Native Peoples: An Independent Journal on Native Affairs 18, 4 (1978): 7–9.

23. Citizenship Sector – bc Native Women’s Society Special Meeting, 1989-90/157 gad, rg6-F, box 1, file 9120-G, lac; Grants files – Indian Homemakers of British Columbia, Pacific Regional Office – Citizenship Branch, Grants Secretariat, 1986-87/186 gad, rg6-f-4, file 0023, box 1, lac; Sharon Donna McIvor, “Aboriginal Women Unmasked: Using Equality Litigation to Advance Women’s Rights,” in Susan B. Boyd, Margot Young, Gwen Brodsky and Shelagh Day, eds., Poverty: Rights, Social Citizenship, and Legal Activism (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2007), 98–99.

24. “bc iha Progress Report,” 31 December 1972–1 November 1973, Urban Planning – Provision of Group Receiving Homes for Native Indian Children – British Columbia Indian Homemakers’ Association, 1972/05/02–1975/03/07, 1987-88/056 gad, rg56, file 116-3-604, box 90, lac. iriw member Philomene Ross led a sister demonstration in Edmonton. iriw, Minutes, 1973–75, Leonard and Kitty Maracle fonds, box 4, file 4-18, ref. code 1351-4-18, Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia.

25. “nac Press Release,” Status of Women News 4, 1 (1977): 8, Rise Up! A Digital Archive of Feminist Activism, https://2ogewo36a26v4fawr73g9ah2-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/nac-statusofwomennews-vol.4-1.pdf; iriw, press release, 22 June 1977, nac fonds, box 125, file 21, Indian Rights for Indian Women, correspondence, June 1977–December 1983, cwma.

26. “Joint Research Project on Indian Women Announced,” Status of Women News 4, 1 (July 1977): 8.

27. iriw, press release, 22 June 1977.

28. R. G. L. Fairweather, Chief Commissioner, Canadian Human Rights Commission, to Kay Macpherson, President, nac, 18 October 1977, nac fonds, box 81, file 1, Indigenous Women’s Rights, cwma; Kay Macpherson, President, nac, to Hugh Faulkner, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, 27 September 1977; Joan B. Neiman, Senator to Kay Macpherson, President, nac, 12 July 1977; Lorna Marsden, President, nac, to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, 21 May 1976, all in nac fonds, box 81, file 2, Indigenous Women, Mary Two Axe Earley Correspondence (hereafter Earley Correspondence), cwma; “Joint Research Project,” 8.

29. Warren Allmand, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, to Brigid Munsche, Secretary, nac, 22 July 1977, nac fonds, box 81, file 1, Indigenous Women’s Rights, cwma; Judd Buchanan, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, to Lorna Marsden, President, nac, 12 July 1976, nac fonds, box 81, file 1, Indigenous Women’s Rights, cwma.

30. Allmand to Munsche, 22 July 1977; Buchanan to Marsden, 12 July 1976.

31. Mary Two-Axe Earley to Lorna Marsden, President, nac, 14 July 1976, nac fonds, box 81, file 2, Indigenous Women, Earley Correspondence, cwma.

32. nac, press release, 13 April 1982, nac fonds, box 81, file 9, Indigenous Women’s Reports and Interviews, 1981–82, cwma. Elsewhere I explore the emotional labour of women’s political activism; see Sarah Nickel, “Therapeutic Political Spaces: Collective Resistance among Indigenous Women in British Columbia,” in Lara Campbell, Michael Dawson and Catherine Gidney, eds., Feeling Feminism: Activism, Affect, and Canada’s Second Wave (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2022), 73–95.

33. Colleen Glenn, iriw, to Kay Mcpherson, nac, 10 March 1978, nac fonds, box 125, file 21, Indian Rights for Indian Women, correspondence, June 1977–December 1983, cwma.

34. Marlene Pierre-Aggamaway, President, Native Women’s Association of Canada, to Jean Wood, nac, 28 May 1981, nac fonds, box 81, file 8, Indigenous Women Correspondence, Invitation, 1981–82, cwma.

35. Pierre-Aggamaway to Wood, 28 May 1981.

36. Kay Macpherson, President, nac, to J. Y. Ranger, Assistant Deputy Minister, Indian and Eskimo Affairs, 13 October 1977; J. Y. Ranger to K. Macpherson, 4 October 1977; Hellie Wilson, Assistant Correspondence Secretary, Office of the Prime Minister, to Kay Macpherson, 31 August 1977; Kay Macpherson to Andrew Delisle, Chief of Band Council, Caughnawaga, 23 September 1977; Joan Anne Gordon to Kay Macpherson, 15 September 1977; nac to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Warren Allmand, 29 August 1977, all in nac fonds, box 81, file 2, Indigenous Women, Earley Correspondence, cwma.

37. Fairweather to Macpherson, 18 October 1977; Macpherson to Faulkner, 27 September 1977; Neiman to Macpherson, 12 July 1977; Marsden to Trudeau, 21 May 1976; Lynn McDonald to Jean Wood, 26 June 1981, nac fonds, box 81, file 6, Indigenous Women Reports and Correspondence, 1979–82, cwma.

38. Lynne McDonald, President, nac, to Pierre Juneau, Under-Secretary of State, 22 May 1980, nac fonds, box 107, file 12, Secretary of State Funding for Native Women’s Programmes, 1980–81, cwma; Marsden to Trudeau, 21 May 1976.

39. Resolutions passed at the annual meeting of nac, 14–17 March 1980, nac fonds, box 81, file 7, Indigenous Women Correspondence, Reports, Memos, 1980–82, cwma.

40. Jean Wood, President, nac, to Caroline Ennis, 11 May 1981, nac fonds, box 81, file 8, Indigenous Women Correspondence, Invitation, 1981–82, cwma.

41. Wood to Ennis, 11 May 1981.

42. Joan Sangster, Demanding Equality: One Hundred Years of Canadian Feminism (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2021); Lara Campbell, A Great Revolutionary Wave: Women and the Vote in British Columbia (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2020).

Familiar Constraints: The Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women and the Challenge of Unpaid Work in the Home

When the Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada released its final report in 1970, that report affirmed the commission’s mandate to “ensure for women equal opportunities with men.”1 It began by recognizing that the existing social norms and values about ideal family forms and sex/gender divisions of labour were central to the existing inequalities between women and men. It called for an equal partnership in marriage – a position affirmed in its starting principles and reiterated in its numerous recommendations.

However, its liberal feminist framework limited its capacity to imagine public policy changes that might really foster the potential for gender equality while leaving intact the basic divisions of labour between households and paid employment. As a result, despite some remarkably progressive recommendations aimed at promoting women’s equality, the report was unable to imagine ways of actually ensuring “for women equal opportunities with men.” Instead, the legacy of the policy framework proposed by the report posed contradictions that continue to shape public policy, challenge feminist organizing initiatives, and leave many women (and increasing numbers of men) struggling with incompatible demands on their lives.2

In 1970 there was a significant correlation between predominant social norms and values and actual practices of a majority of women. Prevailing ideas valued heterosexual marriages and nuclear-family households where the man was the income earner and the woman was an economically dependent wife and mother primarily responsible for running the home:

The traditional wife-and-mother role in the Canadian family is to manage the household, to give affection and backing to the husband, whose occupational life may be largely impersonal and competitive and, in an emergency, to earn money and act as a substitute for the husband. Above all she is expected to carry the major share of rearing the children who consequently often assume prime importance in her life. These are important duties but insufficient prestige is attached to them. (Report, 228)

As the report documented, most married women were primarily involved with child bearing and rearing, responsible for running their households, and economically dependent on their husbands for significant periods of their lives.3

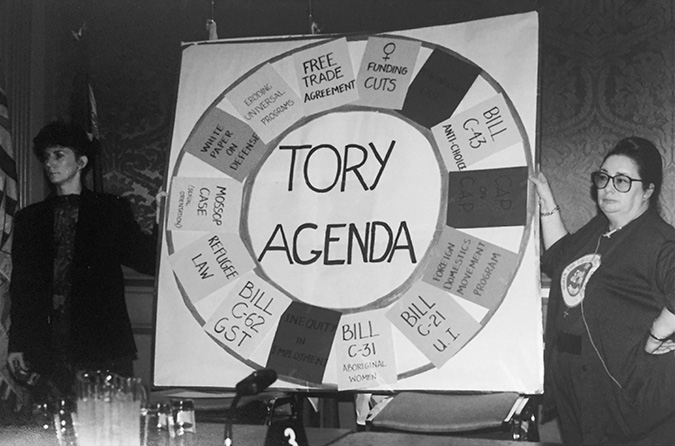

Strategy session before the May 1990 National Action Committee annual general meeting, May 1990, Ottawa.

Courtesy, Alice de Wolff.

The report reflected those values and practices, devoting extensive discussion to marriage, family, divisions of labour, and child care as they related to women’s status in society. Three of its four starting principles dealt with women as wives and mothers, and these consistently informed not only the commission’s analyses and recommendations relating to unpaid work in the home but also its more general analyses:

- Women should be free to choose whether to take employment outside their homes.

- Care of children is a responsibility to be shared by the mother, the father, and society.

- Society has a responsibility for women because of pregnancy and childbirth, and special treatment related to maternity will always be necessary.4

The central contradiction reverberating through the report starts from its first principle, that women should be free to choose whether to take employment outside their homes. Despite its strong support for women’s right to be, as the report put it, “employed full-time in the care of their families and homes” (Report, 31), it also relied on the economic model typical of welfare-state policies at the time – that is, the assumption that paid employment is the most appropriate way for most people to make a living and that the “economy” or the “market” will provide good jobs:

We confidently expect that the situation of women will be generally improved in the future experts foresee. A shorter work day will make it easier for married women to work full-time, thereby avoiding some of the problems part-time work often presents. The combination of a shorter work day and available shift work will allow husbands and wives to work at different times so that they can take turns looking after their family and still spend time together … We hope that the adoption of our recommendations will help more women to find satisfaction in paid work. (Report, 158–159)

In advocating policies that gave “married women a free choice between staying at home or entering the labour force” (Report, 293), the report challenged prevailing cultural norms, illustrated by, for example, a 1976 survey in which 75 percent of people in Canada who responded said women should stay home with their children.5 It also challenged prevailing assumptions about women’s work in the home, presciently anticipating later feminist analyses.

The report was unusual both in its assertion that women’s activities in the home involved work and in its criticism of the widespread devaluation of housewives and their activities. It noted that full-time housewives “comprise one of the largest occupational groups in the economy. Yet they are repeatedly asked, ‘Do you work or are you a housewife?’” (Report, 33). In contrast, it was very careful to respect housewives and the women who “chose” that as their full-time option. The report also made a point of recognizing that most employed women were also housewives, combining their paid work with domestic responsibilities.

The report stressed the extensive amount of work involved in running a home, and it recognized how isolating and exhausting this endless work could be. It was remarkable in insisting that even full-time housewives should be able “to get away from responsibilities on a fairly regular basis” (Report, 36). In addition, it argued that there was a need for trained and adequately paid visiting homemakers to provide support and emergency help. However, it did not comment on how the majority of households might be able to afford such services, naively claiming, “A greater supply of homemakers and trained household workers, and extended day-care services, can do much to meet the general requirements of child care by offering strong support to the basic responsibility of the parents” (Report, 275).

Even more unusual was its assertion that women’s unpaid work in the home was more than just an individual family matter; rather, the report recognized that this work contributed significantly to the national economy. “The housewife who remains at home,” the report insisted, “is just as much a producer of goods and services as the paid worker” (Report, 38). It objected to the exclusion of women’s unpaid work in the home from economic calculations: “The Gross National Product, as measured, fails to reflect a large proportion of women’s work, the full-time production of goods and services by over one-third of the adult population.” The report continued, “In terms of hours spent in production, the omission may have even greater significance. More than one expert has estimated that the number of hours spent every year in household functions alone is greater than the number worked in industry” (Report, 31).

The report summarized the findings of one of the substudies prepared for the commission, which “estimated that the work of housewives amounted to 11 percent of the Gross National Product. In 1968, 11 percent of the Gross National Product in Canada would have been about eight billion dollars.”6 However, the report was reluctant to pursue economic measures of women’s work in the home, partially because “there are problems in evaluating the unpaid production of goods and services in money terms for inclusion in the Gross National Product” (Report, 31) and more importantly, “To view the housewife’s work in the economic sense that money determines value is to distort the picture of her contribution to the economy.7 Such a concept, even if it imputes a money value to her work, fails to recognize those of her functions that can never be measured in money terms” (Report, 32). Instead, the report went on, “Since these functions arise from her relationship with other members of the family, we deal with them in the Chapter on the family” (Report, 32). Despite the report’s objection to the lack of economic accounting for women’s work in the home, it offered no suggestions as to how federal policies might take such contributions into account or how women might be recognized or compensated for their labour. It did not ask whether or how this labour could be recognized and valued in public policies. However, as activists subsequently organized around this issue, they identified a range of options, starting with measuring the amounts of work done and evaluating their contribution to national economies.8

Despite its explicit efforts to recognize and value women’s work in the home, the report was clearly sympathetic to the emerging trend of women opting for paid employment outside the home. It noted the challenges that prevailing norms and changing practices posed for many women:

The widespread assumption that wives are responsible for the home has particular repercussions in today’s world. It is apparent that many wives feel they are being torn between conflicting values. On the one hand, the traditional division of labour makes the care of the home and family the woman’s responsibility. On the other hand, the need for more workers with the skills that some housewives possess is being emphasized in many quarters. With experts offering advice on all sides, even the best adjusted wife is likely to wonder whether or not she is on the right course. (Report, 52)

Accordingly, many of the report’s recommendations concentrated on access to paid labour and on the removal of barriers facing women in the paid labour force. While it documented the extensive discrimination facing women who entered the paid labour market, and made numerous recommendations intended to provide women with the same opportunities as men, one of the most challenging obstacles it noted was child bearing and child care. Notably, care for frail seniors or sick or disabled adults was not included in its concerns, although women were clearly providing this care at the time.9

The report’s second starting principle stated that “care of children is a responsibility to be shared by the mother, the father and society” (Report, xii). This assertion that child care is not exclusively a family responsibility but also a social responsibility was perhaps the report’s most significant challenge to existing norms. Arguing that “society may be legitimately called upon to contribute to community services for its younger generation,” it called for financial support for all dependent children “whether the mother stays at home or works outside” and whether the costs are measured “in cash outlays or in time devoted to care and supervision or both” (Report, 261, 302). It noted that “for the mother who works at home, this cost might be valued in terms of the cash income she foregoes by looking after children at home instead of taking paid employment” (Report, 302). It also called for a guaranteed annual income for one-parent families with dependent children (Recommendation 135), a recommendation still debated today but never implemented.10 A national program for the provision of daycare, regardless of parents’ employment status – at the time a remarkably forward-looking and radical suggestion – was similarly recommended (see Lisa Pasolli’s contribution to this roundtable). The report’s third starting principle maintained that “society has a responsibility for women because of pregnancy and child-birth, and special treatment related to maternity will always be necessary” (Report, xii). Based on this, it called for paid maternity leaves for women employed in the federal public service, since it could only make legislation recommendations for those workers covered by a federal labour mandate, although it clearly supported a wider system of maternity leave.11

In many ways, the report’s approach reflected a classic liberal feminist position, supporting women’s right to make the choice to stay at home or seek paid employment. This position echoes those of many advocates of women’s rights who have called for women’s equality with men in education and in the paid labour force while supporting women’s choice to be at home, especially with their children; recognized that independent income earning is important for women’s equality while also recognizing that mothers depended on support from husbands and their community; and called on fathers and society to take responsibility for children without examining what that might involve in practice.12