Labour / Le Travail

Issue 90 (2022)

Article

“The Same Tools Work Everywhere”: Organizing Gig Workers with Foodsters United

Abstract: Foodsters United, a workplace organizing campaign by Toronto food couriers, shows that, even in the gig economy, the classic organizing methods work. The Foodsters successfully challenged their misclassification as independent contractors, got over 40 per cent of a large workforce to sign union cards, and triggered a union vote that they won with 88.8 per cent support. These victories were tempered by a devastating setback: their employer, Foodora, exited from Canadian markets. Nevertheless, what Foodsters United achieved through workplace organizing sustained its transformation into Gig Workers United, which is organizing all delivery platform workers in Toronto. Although platform companies like Foodora promote the idea that the gig economy is unprecedented, its historical continuities are more important than its discontinuities. This is also true of the workplace organizing in the gig economy. Foodsters United achieved substantial victories, not because they invented new organizing methods but because they adapted the classic methods, in often ingenious ways, to their gig economy workplace. This article is based on interviews with the campaign organizers. It is organized thematically according to classic workplace organizing methods, particularly those developed in the industrial organizing tradition, including organizing conversations, mapping, charting, leader identification, issue identification, and the creation of democratic organizations.

Keywords: gig workers, gig economy, platforms, labour organizing, unions, union democracy, couriers, covid-19, misclassification

Résumé : Foodsters United, une campagne de syndicalisation en milieu de travail menée par des coursiers alimentaires de Toronto, montre que, même dans l’économie des petits boulots, les méthodes de syndicalisation classiques fonctionnent. Les Foodsters ont contesté avec succès leur classification erronée en tant qu’entrepreneurs indépendants, ont fait signer des cartes syndicales à plus de 40 pour cent d’une main-d’œuvre importante et ont déclenché un vote syndical qu’ils ont remporté avec 88,8 pour cent de soutien. Ces victoires ont été tempérées par un revers dévastateur: leur employeur, Foodora, s’est retiré des marchés canadiens. Néanmoins, ce que Foodsters United a réalisé grâce à l’organisation du lieu de travail a soutenu sa transformation en Gig Workers United, qui organise tous les travailleurs de la plateforme de livraison à Toronto. Bien que les sociétés de plateforme comme Foodora promeuvent l’idée que l’économie des petits boulots est sans précédent, ses continuités historiques sont plus importantes que ses discontinuités. Cela est également vrai de l’organisation du lieu de travail dans l’économie des petits boulots. Foodsters United a remporté des victoires substantielles, non pas parce qu’ils ont inventé de nouvelles méthodes d’organisation, mais parce qu’ils ont adapté les méthodes classiques, de manière souvent ingénieuse, à leur lieu de travail de l’économie des petits boulots. Cet article est basé sur des entretiens avec les organisateurs de la campagne. Il est organisé de manière thématique selon les méthodes classiques d’organisation du lieu de travail, en particulier celles développées dans la tradition d’organisation industrielle, y compris l’organisation des conversations, la cartographie, la mise en tableaux, l’identification des dirigeants, l’identification des problèmes et la création d’organisations démocratiques.

Mots clefs : travailleurs et travailleuses à la demande, économie à la demande, plateformes, syndicalisation, syndicats, démocratie syndicale, messagères et messagers, covid-19, mauvaise classification

Foodsters United, a workplace organizing campaign by Toronto food couriers, shows that, even in the gig economy, the classic organizing methods work. These couriers, working for the Foodora platform, faced many of the challenges common among gig workers. Their work was unpredictable, was poorly compensated, and had high turnover. Foodora classified these couriers as self-employed independent contractors, which deprived them of the labour and employment rights that most employees achieve, including the right to unionize. Their workplace was the size of a metropolis and lacked any central brick-and-mortar worksite. Furthermore, when they began organizing, they did not know how many co-workers they had, let alone who most of them were. And yet, despite some missteps and setbacks, Foodsters United achieved significant victories.

Foodora, a brand of Berlin-based company Delivery Hero, entered Canadian markets in 2015. Toronto couriers began organizing in May 2018, and a year later, on May Day 2019, Foodsters United went public with the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (cupw). The Foodsters successfully challenged their misclassification as independent contractors, got over 40 per cent of a large workforce to sign union cards, and triggered a union vote that they won with 88.8 per cent support. These victories were tempered by a devastating setback: in April 2020, Foodora announced the company’s exit from Canadian markets. Nevertheless, what Foodsters United achieved through workplace organizing sustained the campaign as it transformed, in February 2021, into Gig Workers United, a community union organizing all delivery platform workers in the Greater Toronto Area (gta).

Platform companies like Foodora often promote the idea that the gig economy is unprecedented.1 They proclaim their platforms – that is, applications, or “apps”: the internet-connected software that quickly matches different parties in various transactions – the “future of work.” But in many respects, this is actually a return to the casual, on-demand labour that has been the norm under capitalism.2 And if the gig economy features more historical continuities than discontinuities, so too will the workplace organizing that occurs within it. Gig workers face significant challenges, but if they accept these claims about their unprecedented situation, they might neglect the traditions of workplace organizing that workers have crafted over centuries.

In light of this, the case of Foodsters United is worth considering. The campaign achieved its substantial victories not because the Foodsters invented new organizing methods but because they learned and adapted the classic methods, in often ingenious ways, to their gig economy workplace. In particular, they creatively applied techniques such as structured organizing conversations, social mapping and charting, and identification of strategic chokepoints. Gig workers everywhere can draw lessons from their achievements, their mistakes, and what they learned about organizing as their campaign developed.

Commentators are sometimes confused as to whether the gig economy is something new or old. On the one hand, they argue that it entails technological revolutions and social upheavals that require entirely new concepts. On the other hand, they contend that these platforms are capturing so much of the market, are exacting rents from so many different parties, that the gig economy is best described as feudal or medieval.3 With this odd blend of futurism and anachronism, it is almost as if the gig economy is the world of Dune, where we expect to see spaceships coexisting with barons and dukes. Nevertheless, the gig economy is not the cutting edge of feudalism. It is capitalism.4

The platforms facilitate three kinds of transactions: (1) renting non-labour commodities (e.g. Airbnb); (2) selling non-labour commodities (e.g. eBay); and (3) selling labour power as a commodity (e.g. Uber). The third of these is gig work proper. The platform mediates not only the work itself but every part of the work process, including being hired, matched with customers and clients, supervised, disciplined, and paid. For this reason, even if gig workers provide most of their own equipment, such as cars or bikes, the most important piece of equipment, the platform itself, is the primary condition of production.5 Therefore, the workers employed through the platform are wage labourers, the owners who control it are capitalists, and the percentages they take from each transaction are not rents, fees, or commissions but profit from the labour of gig workers.6

Traditionally, a “gig” meant a one-time or short-term transaction, without any commitment to a continuous relationship, often as a supplement to a main source of income. The platform companies have adopted the term to invoke the romantic ideal of the musician and their agreements with different venues.7 But those who do platform labour have reclaimed the term by increasingly identifying as gig workers. Although much casual labour occurs outside of these platforms – and thus, in this sense, gig work is broader than platform work – in this article, I use these terms interchangeably.

Gig work is a departure from full-time, permanent work for a single employer who supplies most of the equipment in a central worksite. Nevertheless, this “standard employment,” which often provided stability, decent compensation, and union representation, has historically been the exception.8 It gained prominence only in the postwar era, and even then, it usually excluded occupations that tended to employ women, racialized workers, and migrant workers. Gig work, which is typically casual labour that is paid by the task, not the hour, has much in common with “non-standard employment,” the norm under capitalism.9 Indeed, gig work is part of a broader resurgence, since the neoliberal turn of the 1970s, of temporary and unpredictable work with low wages, few benefits, and sparse union representation.

Since gig workers are typically classified as independent contractors, they find little support from legal and regulatory institutions. Instead, they rely on their workplace positions in production and distribution processes to gain leverage against their employers.10 Some gig workers provide in-person services, either in more public settings, like transportation, or in more private settings, such as household cleaning. Others work online from around the world, either through low-skilled “crowdwork,” like labelling images, or more high-skilled freelance work, such as software engineering. Gig workers in transport, logistics, and some delivery sectors have relative advantages because they have more disruptive power. Their location between producers and consumers, particularly when there are economies of scale, means that their direct actions, like work stoppages, are more likely to have ripple effects throughout the economy.11 Nevertheless, all gig workers are widely dispersed across their worksites. In more centralized workplaces, a single worker can be quite disruptive, whereas gig workers depend disproportionately on collective action.12

And that is why the classic organizing methods remain relevant, especially those developed in the industrial-organizing tradition when unions were not legally recognized.13 Although we associate industry with the centralized worksite, the impetus for industrial organizing is uniting all workers across workplaces whatever the divisions between trades, skills, or identities. This “wall-to-wall” organizing can be effective even in workplaces without walls.

The literature on the gig economy has covered many important themes, but it features a major gap: commentaries on gig worker organizing have been neither concrete enough, by showing in precise detail how each of these organizing methods can be applied to the specific challenges of the gig economy, nor comprehensive enough, by showing how all of these methods can be integrated into the overall strategy of an entire campaign. Scholars of the gig economy have sought to define it and situate it historically.14 They have researched the extent and composition of the gig workforce and the variations in workers’ experiences.15 Scholars have scrutinized their classification as independent contractors and their lack of social protections.16 They have studied discrimination and inequality in the gig economy, particularly with respect to gender but also in terms of race and status.17 However, the latter are relative research gaps.18 Scholars have also investigated how platforms surveil and discipline users through data production and collection, sell this data to third parties, de-skill gig labour, and threaten gig activists with automation.19

Much of the scholarly and popular writing on the gig economy has discussed workplace organizing. Nevertheless, these analyses tend to be either general or narrow. Most of these commentators offer useful but broad surveys of gig worker organizations, activities, or efforts to forge common identities, or syntheses of all three.20 Even those commentaries that provide narrative accounts of gig worker campaigns tend to speak in general terms, without going into precise details of how these organizing methods were conceived and implemented in practice.21 Conversely, when scholars do provide more detailed descriptions, they usually limit their analyses to one or two organizing methods.22 Some popular commentaries, however, have explored more.23

This article bridges the comprehensiveness of the general accounts with the concreteness of the narrower accounts by providing the kinds of details and illustrations found in workplace organizing manuals, including by reproducing campaign materials, because these organizing methods cannot be truly understood in merely general terms. The details are indispensable. For example, this article shows how the Foodsters meticulously adapted social charting to their gig economy conditions. Aside from the high turnover in the traditional sense, their platform employer could deactivate and reactivate their co-workers’ accounts at will, or launch hiring sprees without needing to guarantee much work. This widened the gap between those who deem this work their main gig or just a side gig.

There is another reason for the details I offer here. Those who study gig workers and their organizing often do so because they sympathize with their struggles. For this reason, these accounts, like sympathetic portrayals of the labour movement in general, are often celebratory. Scholars outside of these campaigns are impressed by the obstacles that gig workers must overcome, and insiders are personally invested in their campaigns. While there is much to celebrate, it is also important to discuss the messy process of trial and error found in every campaign, including this one. Foodsters United made some mistakes and much was learned along the way. If I dwell on a few of the things they wish they had known from the beginning, it is so that gig workers elsewhere can anticipate those things as they begin organizing their own workplaces.

This article draws from semi-structured interviews with eleven Foodora couriers, one union staff organizer, and one campaign lawyer. Recruited through snowball sampling, interviewees were chosen because they were some of the main organizers of the campaign, had joined throughout its various phases, and were from different work groups and social groups.24 This article is organized thematically according to classic workplace organizing methods, including organizing conversations, mapping, charting, leader identification, issue identification, and the creation of democratic organizations. It explores the creative ways in which Foodsters United applied these classic methods to their gig economy workplace.

Organizing Conversations

The most successful organizing was based entirely on the one-on-one conversations. That proved, in some ways, this workplace is not exceptional at all.

—Chris

Williams

It all began in May 2018 when eight Foodora couriers met one evening in Christie Pits Park in downtown Toronto. They discussed their declining working conditions, their decreasing pay, and the more rigid scheduling Foodora had introduced.25 “It’s just shitty drug dealer logic,” notes Thomas McKechnie. “They’ll give you a year of good treatment and once you’re locked in, they’ll take the bottom out of it.”26 Only one of them had done any union organizing. Matt Gailitis, formerly with the Services Employees International Union, thought that the couriers could successfully challenge their classification as independent contractors.27 Matt had organized with personal support workers and believed a union drive was possible in the couriers’ decentralized workplace. These eight couriers agreed to continue meeting every Monday night. The campaign that would soon become Foodsters United was born.

Early on, these conversations were unwieldy. Nevertheless, they soon refined their techniques, especially after an “Organizing 101” workshop with the Industrial Workers of the World (iww), who had members working for Foodora. The couriers learned the importance of one-on-one organizing conversations with co-workers. They began contacting known and potentially sympathetic co-workers, and while working, they initiated conversations with couriers they spotted wearing Foodora’s bright pink bags and gear. After these conversations, they invited co-workers to the Christie Pits meetings, where the organizers used the classic aeiou model: Agitate, Educate, Inoculate, Organize, Unionize.28

Every Monday night, the organizers would begin the conversation with agitating by asking open-ended questions about their workplace, which shows co-workers that they care about issues and want them to change. Then they turned to educating by laying the blame on Foodora, which had the power to address these issues but would only do so if couriers applied collective pressure. They then began inoculating by giving their co-workers a dose of the anticipated criticisms of their collective efforts, because if they heard them first from fellow couriers, they would know how to respond later when exposed to them from the company. Foodora would likely argue, for example, that the union would turn courier work into a standard 9-to-5 job, targeting couriers who wanted more independence and flexible schedules. Eliot Rossi notes that the campaign countered this criticism by persuading the couriers that it was Foodora that was gradually eroding their independence.29 The organizers would then emphasize the importance of organizing – of each courier committing both to collective activity and to specific tasks, say, by initiating similar organizing conversations with three of their co-workers. It was only then, after gauging the mood of the meeting, that the organizers would discuss the need for unionizing. In those early meetings, though some attendees had reservations, none were hostile, and 90 per cent agreed to sign union cards.30

As the campaign expanded, some couriers deemed the traditional organizing principles ill suited to a workplace that stretched across a metropolis. The prospect of in-person conversations was daunting when they had no idea how many couriers worked for Foodora. Some thought social media would be the superior outreach tool, but they realized its limits as the campaign developed. A group chat with hundreds of couriers impedes organizing if only five to ten couriers participate consistently.31 If co-workers gave their Facebook account as contact information, they often remained disengaged, but a phone number usually meant meaningful commitment. Ultimately, the Foodsters decided to prioritize street outreach and one-on-one conversations. They found that although social media can promote events to co-workers who are already active, it will not activate them: “No one ever joined a union because of a Trump meme.”32

As Foodsters United grew, they contacted several unions. One of the few to respond was the one most of the couriers were hoping to work with anyway.33 On 7 January 2019, Foodsters United voted unanimously to join cupw. On 27 March 2019, cupw organized an all-day training, where Liisa Schofield, a staff organizer, discussed some organizing methods and asked the couriers to apply them to the workplace they knew better than anyone.34 One advantage of this decentralized workplace is that couriers can have organizing conversations during work, because management is not looking directly over their shoulders. Nevertheless, the pressures to deliver as fast as possible constrained the traditional organizing conversation. At the training, the couriers developed the stoplight conversation, a ten-second chat they could have with co-workers at intersections. As Iván Ostos demonstrates, they would pull up beside a courier and say something like,

“Hi, I’m Iván. How do you find this work?”

“Yeah, this shift sucks, I’m not making a lot of money.”

“Can I get your contact info so we can talk about it later?”

“You have that and you move on,” Iván continues, “because they’re hustling too.”35 The couriers also created the ride-along conversation.36 If a co-worker was rushing to a delivery, organizers would ask to ride beside them to discuss working for Foodora. Car couriers were particularly receptive, because having a passenger during their delivery meant they avoided paying for parking.

Through these organizing conversations, the Foodsters discovered the issues that mattered most to their co-workers.37 They eventually arranged these issues into three categories: compensation, health and safety, and dignity. The issue of compensation included low wages and few benefits, especially because as independent contractors they lacked minimum standards and entitlements.38 Furthermore, providing and maintaining most of their own equipment is costly, particularly for car couriers, who must also pay for regular parking tickets.39 In terms of health and safety, courier work is dangerous.40 When gig workers are independent contractors, their employers are not liable for workplace injuries; workers bear the expenses and lost wages.41 Unlike most gig companies, Foodora did pay into the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB), but because Ontario’s employment laws are based on standard employment with more regular hours, when a workplace injury prevented Iván from working for months, he received only $210 per week, barely enough for rent.42 The third category, dignity, addressed issues like the workers’ misclassification. In addition, the Foodora app relied not only on algorithms but also on human dispatchers, who could assign orders to particular couriers, temporarily suspend a shift, sign them out of the app altogether, and record couriers in a “strike log,” which could result in penalties and punishments.43 Indeed, Foodora could arbitrarily deactivate a courier’s account without any formal appeals process.44

Organizers are taught to ask open-ended questions and to listen more than they speak so that they can discover the issues that matter most to the diverse groups of co-workers they are trying to bring into a majority participation campaign. As the Foodsters’ outreach expanded and the primarily male couriers spoke to more women and trans co-workers, they learned about gendered discrimination in their workplace. Since the app used personal phone numbers, women couriers in particular faced harassment when, for example, customers called them after deliveries to ask for dates. Alex Kurth notes that this issue, and the Foodsters’ demand that Foodora implement veiled phone numbers, “would never have occurred to me, but once that came up it became a really big issue that we got a lot of traction around.”45

The couriers also developed their inoculation techniques. The organizers met regularly after outreach, discussed tough questions asked by co-workers, and developed informed responses. Nevertheless, this did not always go smoothly. One question in particular proved very tough, especially in retrospect: What if unionizing causes Foodora to leave the country? This was on the mind of many couriers, because Foodora had closed all operations in Australia in August 2018. The Foodsters developed their response: Foodora had left Australia not because of a union drive but because the tax bureau ruled that the company owed $8,000,000 in back taxes and unpaid wages.46 Furthermore, though Foodora had never been profitable in Australia, it was expanding rapidly throughout Canada.

Since Foodora did ultimately leave Canada, however, some couriers later expressed regret for this response. “It was bad organizing,” says one courier, because organizing training teaches you that when speaking to co-workers about unionizing, “if someone asks, ‘Can they fire you?’ you always say, ‘Yes, they can.’ Because it can happen, even though it’s illegal.”47 This courier felt that, though most of the organizers thought Foodora would never leave Canada, they should not have spoken with such certainty. Even if this makes it harder to persuade co-workers to commit to the campaign, “With things you’re unsure about, you just have to be honest with people.”48 The organizers are better able to address this issue since Foodsters United became Gig Workers United, which, as a community-based workers’ organization, is organizing not just in one company but across the industry.49 Nevertheless, there was still much to be built before that transition became possible.

By April 2019, Foodsters United decided they had exhausted their covert outreach strategies. It was time to go public. In Ontario, triggering a union certification vote requires 40 per cent of the workers in a proposed bargaining unit to sign union cards. Typically, a union drive will wait until they have exceeded this threshold to apply for certification. In a workplace that is so large and decentralized, however, the Foodsters needed to go public much earlier so that they could uncover the rest of the fleet. “We made a best guess of how many people worked for the company,” Liisa notes, “because we can’t count people coming in and out of the factory gates.”50 They had 120 union cards signed and estimated that there were around 800 couriers, which meant they would need at least 200 more cards to achieve the 40 per cent threshold.51 Foodsters United decided to go public on 1 May 2019.

Between a morning press conference and the May Day parade, around 60 Foodsters announced themselves directly with a collective bike ride to Foodora’s King Street headquarters. Dylan Boyko, who worked as a dispatcher and a courier, recalls dispatching in the office that day.52 Suddenly, people from the various departments rushed to the windows to see a commotion down below. In the parking lot, a bright pink horde was chanting:

Gig economy,

Same old crap!

Exploitation,

In an app!

The nervous Foodora staff, management, and executives were now confronted by the people “on the other side of the screen.”53 Dylan notes, “In the office, we’re sitting at a computer, and you often forget there are real people out there doing all the work.”54

The day after Foodsters United went public, Iván initiated an organizing conversation with another courier while they waited for their orders at a restaurant.55 The other courier said he was not interested in a union because this was only a side gig. This poses significant challenges for workplace organizing, because gig workers who depend more on the platforms for their main income tend to experience greater precarity, job dissatisfaction, and affinity with unionizing, while those who use the platforms to supplement their main income tend to feel more autonomy, satisfaction, and sympathy for the company.56 Iván was unable to persuade his co-worker, who, when his delivery was ready, left the restaurant looking slightly annoyed. An Uber driver waiting at the intersection saw the bright pink Foodora bag and shouted to the baffled courier, “Aren’t you excited?! Can I join the union too?!”

Mapping

Finding our co-workers was 90 per cent of our strategizing. Everything we did after that was comparatively easy.

—Alex Kurth

An important part of workplace organizing is social mapping.57 Workers are encouraged to draw large maps of their workplace and to locate the different work groups and social groups, as well as to assess their relations to one another and to management. Mapping also illustrates which groups are not yet participating sufficiently in the campaign. Furthermore, by mapping how work is conducted, including the different tasks and lines of motion, workers can identify bottlenecks. When these bottlenecks are made the target of actions, such as work stoppages, they can become chokepoints that increase workers’ disruptive capacity and their leverage against the employer. Nevertheless, in the gig economy, how can workers map a workplace that is the size of a metropolis and has no central brick-and-mortar worksite?

Before Foodsters United could pursue organizing methods like leader identification and issue identification, they first needed to develop their co-worker identification. This required extensive social mapping. They had some advantages in this respect, because couriers are cartographers: “Delivering in the city is also mapping the city. You’re constantly looking at maps, keeping lists of restaurants, knowing where the hubs are.”58

Workers are already organized

Workers never need to organize from scratch. Even if there has been no formal organizing at a workplace, co-workers might carpool together, attend the same house of worship, or belong to the same migrant community. If an organizer can identify these organic groups, reaching one member might be a way to reach the rest.

The first group the Foodsters identified was the downtown courier community. Although it had emerged among bike messengers decades prior, many of them were now also working for food delivery apps like Foodora. The messenger community – or “Mess Life” – is a fully developed subculture.59 Messengers see themselves as “cowboys of the streets” who would rather make less money if it means keeping their independence.60 “There’s a genuine dignity to that,” Chris notes, “the way you hold weather and the elements in contempt. I don’t think it’s just machismo.”61 The best example of this is Toronto’s major contribution to global courier culture: the alley cat race.

An alley cat is an unsanctioned street race created by Toronto bike messengers in 1989. There is no set course. At the start, participants are given a list of checkpoints around the city that they must visit before crossing the finish line. Carefully planning the route is as important as riding fast and navigating traffic. By knowing the best roads, busy spots, and shortcuts, racers demonstrate the skills that make them good messengers.62 Alley cats became so popular around the world that every year a different city hosts the Cycle Messenger World Championships. Leah Hollinsworth, a veteran Toronto bike messenger, describes it as “a family reunion where everybody is the weird uncle.”63

Early in the campaign, the Foodsters encouraged their co-workers to participate in this courier culture, including the mutual aid networks for recovering stolen bikes, the weekly gatherings at Trinity Bellwoods Park, and, of course, the alley cats. “I had to convince them,” Alex notes, “it’s not about the race, it’s not about how you place, it’s about the community.”64 It was a natural place to begin organizing conversations.

As the campaign progressed, however, the Foodsters learned that they had overestimated the importance of this community: “There was an initial sense that they were an essential plurality within the organization, when in fact they were just the people who we knew the most.”65 After the union drive went public, Thomas notes, “We realized we were meeting hundreds of people and none of them were beardy old couriers.”66 Instead, they were migrants, students, parents, and suburbanites. The Foodsters recognized that if Foodora’s business model extended far beyond the messenger world, so must their organizing.67 The campaign expanded its social mapping by developing one organizing technique in particular: identifying chokepoints.

Chokepoints

Since organizers cannot be everywhere at once, it is important to identify chokepoints, namely “a lot of people streaming into a small area.”68 Using their knowledge as workers, they identified the busiest intersections, such as Spadina and Richmond, where there is a popular restaurant on every corner, dedicated bike lanes on both streets, and traffic lights that change every 45 seconds – plenty of time for stoplight conversations. The intersection even has a recognizable landmark: a statue of a giant thimble commemorating the International Lady Garment Workers’ Union, which in 1931 went on strike against the sweatshop conditions in the historic Garment District that surrounds the intersection.69

The Foodsters decided to have couriers at the thimble every day with an outreach tent, water, bike lights, and union cards. When the campaign was still covert, a great night meant speaking to 20 couriers and getting 5 to sign cards.70 At these intersection chokepoints, however, in a four-hour shift the Foodsters could see 200 couriers bike through, meet 20 to 30 of them, and get 10 to 15 to sign. After each organizing conversation, they put laminated cards in the courier’s spokes so they knew to whom they had already spoken. They borrowed this idea, “a part of the language of downtown couriers,” from the spoke cards given to racers in the alley cats.71 Since the couriers lacked a central workplace, when the Foodsters created these permanent sites, if a courier could not talk in the middle of their delivery, they could circle back later, or go there just to socialize with their co-workers.

One of the most important chokepoints was Union Station, the central transit hub for downtown Toronto. The organizers noticed that many co-workers, especially South Asian couriers, were riding electronic bikes, or “e-bikes,” in the area. The Foodsters soon realized that these couriers often lived in the outer Toronto suburbs, or even other cities in the gta, and commuted by train into the more lucrative downtown core. They often kept their e-bikes overnight at Union in a particularly secure locking station. Ahmad J., a migrant courier who commutes from Whitby, estimates that 80 per cent of the bikes locked there belong to couriers.72 Since recent migrants to Canada face substantial barriers to employment that matches their education and skills, many turn to gig work.73 Indeed, Ahmad, a Syrian refugee, has a degree in electrical engineering.74 The Foodsters did frequent outreach at the Union Station chokepoint so that they could have more organizing conversations with migrant couriers.

These chokepoints helped identify the couriers working in the downtown zone but not those in the four other zones, ranging from Mississauga in the west to The Beaches in the east and extending up from Midtown to North York. These zones had fewer couriers dispersed across larger spaces. They were more likely to be worked by car couriers, who were harder to identify than the bike couriers with their bright pink backpacks. Furthermore, there were fewer organic groups among car couriers. Houston Gonsalves, a car courier, had never met another courier while working until Alex Kurth initiated an organizing conversation.75 The Foodsters identified particularly busy streets and restaurants for car couriers and did stoplight conversations.76 They also translated campaign posters into Punjabi, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, and Urdu and placed them at the popular gas stations and car washes they had identified.77

In one of their most inspired strategies, the Foodsters reached these couriers by “flipping everything on its head.”78 As Thomas notes, “If you don’t know where people are, bring them to you.” In places where they had difficulty finding new couriers, they ordered food from Foodora and had organizing conversations with whomever arrived for the delivery. They also expanded this tactic with “order-in days.”79 cupw trained allies to do organizing conversations; these allies would then, en masse, order food from Foodora, talk about the union to whomever showed up, and try to get their contact information so that the Foodsters could start a fuller conversation. The Foodsters also brought their co-workers to them by hosting well-attended workshops on topics such as filing taxes as an independent contractor and fighting parking tickets.

Charting

I can say this to anyone trying to unionize a decentralized workplace – if there’s any way that you can get an employee list, do everything you can to get it because it’s so difficult

doing it without. It’s not impossible, but if there’s any way you can get someone on the inside to get you an employee list, it will save you so much trouble.

—Alex

Kurth

A crucial part of workplace organizing is social charting.80 A chart is a list of all known co-workers and any information necessary to assess their relations to their work, to one another, and to the campaign. In the gig economy, however, how can workers do social charting when they do not know how many co-workers they have, let alone who they are?81 In companies where it is even more difficult to get an employee list – such as Uber Eats, where the greater reliance on algorithms reduces potential connections between workers on the ground and in company offices – social charting becomes even more important.

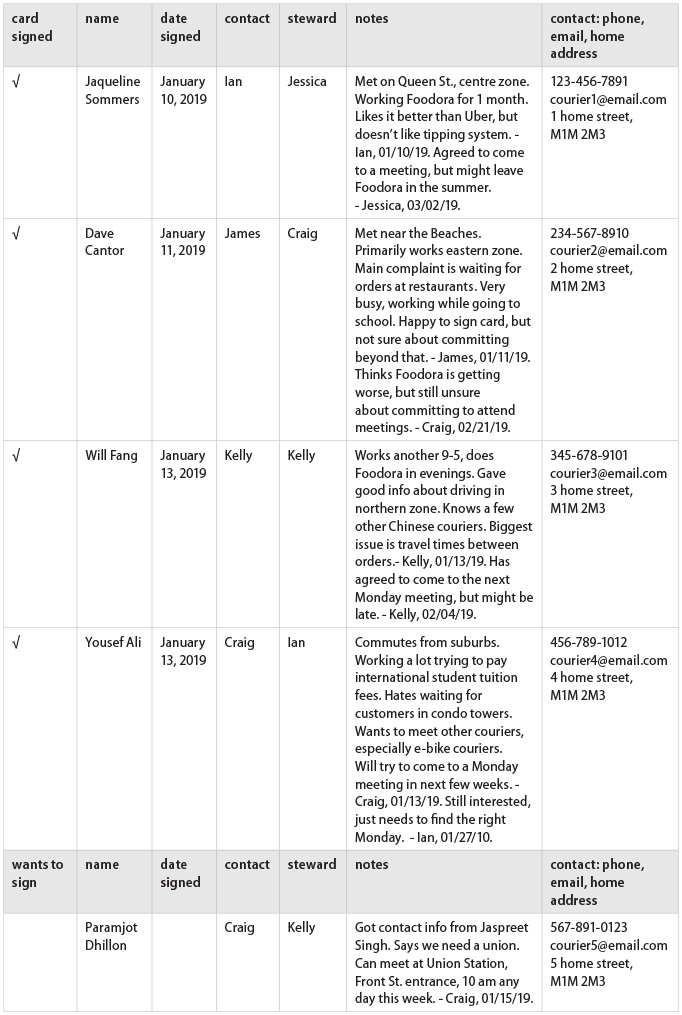

Much of the information recorded by the Foodsters is typically found in workplace charting. They recorded the “contact,” the person who has a connection with a co-worker or who had made one. They also had a committee of stewards they assigned to co-workers based on availability and best fit, such as shared interests. In their notes on each co-worker, they recorded their main issues and assessed what they thought about the union drive. This assessment is particularly important because of the often contrasting experiences between those who deem gig work their main hustle and those who consider it a side hustle. Foodora couriers who depended on gig work for their main income were much more likely to agree with, and participate in, the union drive.82 Through this assessment, the Foodsters categorized co-workers according to who had signed a card, who wanted to, who had been approached but was unsure, who was against the union, and who was unresponsive (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The main social chart, part 1.

Note: The author has seen a sample of the social charts from which all personal information had been redacted. In Figure 1, as with all other charts in this essay, I provide representative reproductions, but all names and personal information have been invented by the author.

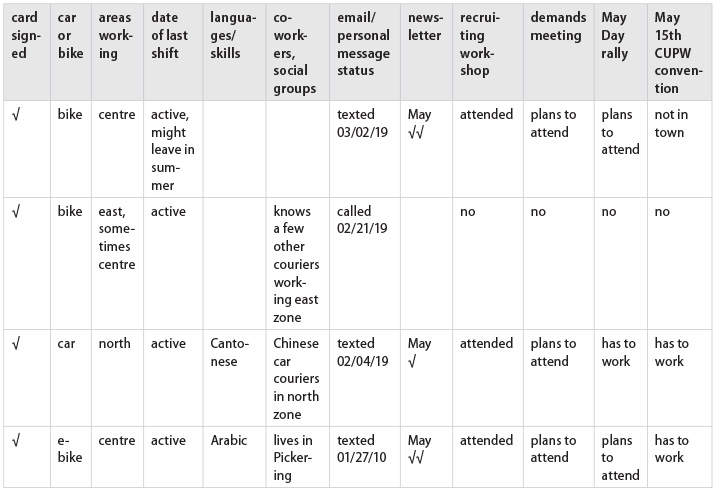

Along with other important information, the Foodsters also recorded engagement, including who had opened the latest campaign newsletter (√) and who had read it (√√), responses to emails or personal messages, and meeting attendance. They also tracked who was actively working, or, if not, the date of their last shift worked (Figure 2). As we will see, this is hugely important for charting gig work with such high turnover.

The Foodsters knew from the outset that their co-workers were primarily male and that bike couriers tended to be younger than car couriers. Nevertheless, their charting gradually revealed a fuller picture of the workforce. Many of the couriers, especially those living in the outer suburbs and other cities in the gta, were racialized and migrant workers.83Foodora, unlike most other app companies, did not check the immigration status of couriers, which likely meant a higher proportion of undocumented workers.84Besides the “white” couriers more likely to live downtown, major demographic groups included South Asian (especially Punjabi students), Middle Eastern, Chinese, and East African.85

Charting and mapping informed each other when, for example, the Foodsters realized that many couriers working in the downtown core were Punjabi students commuting from the Peel region.86 In addition to making Union Station an important chokepoint for outreach, the Foodsters’ charting helped them develop other strategies to reach these couriers. Foodsters United advertised the campaign on the relevant trains and concentrated their poster and flyer distribution in places like Sheridan College where Punjabi students are most likely to attend.87 In one of the more fascinating developments in this campaign, cupw staff discovered that they needed to map and chart their own membership, because casual or temporary postal workers were also doing gig work, particularly South Asian members in the Peel region.88

Figure 2. The main social chart, part 2.

Note: This continues the chart in Figure 1 but shows only the information for those who signed cards, which is sufficient for illustration purposes.

Stacking the list

When a union applies to certify, employers must give the Ontario Labour Relations Board (olrb) a list of the employees who would be in the prospective bargaining unit, though they sometimes “stack the list” with names that do not belong. If the union does not identify and challenge these ineligible names, they can pass by unnoticed. This falsely inflates the number of employees and makes it harder for the union to get 40 per cent of their prospective members to sign union cards. The gig economy relies so heavily on casual work that it is much easier for gig companies to stack the list.89 Foodsters United prepared for this possibility by developing new elements of what was already rigorous charting. This was a crucial feature of their co-worker identification.

If the olrb overturned their misclassification, the Foodsters did not know who the labour board would deem an active worker and thereby a member of the prospective bargaining unit. Foodora would likely claim that an active worker is anyone who had created a courier account, even if they had never worked a shift, because this would make the employee list as large as possible. Ryan White and the rest of cupw’s legal team would argue that it should be anyone who had worked a shift within four weeks of the application to certify.90 This met the legal criterion of an active worker – those workers most tied to the particular workplace – because the contract stipulated that Foodora could deactivate anyone who had not worked a shift in four weeks. In the Foodsters’ charting, however, they had to assume that it could be either of these or anything in between.

In these conditions, the ideal chart would include the total number of couriers (1) with courier accounts (the largest possible number of people who Foodora could claim are active workers); (2) who had worked at least one shift (the next largest number); and (3) who had worked a shift within certain periods of time, say, in the last (a) year, (b) eleven months, (c) ten months, and so on. Each of the totals of active workers would show the Foodsters how many signed cards were needed to reach the 40 per cent threshold, whatever the olrb decided.

The Foodsters attempted to get as close to this ideal chart as possible.91 During organizing conversations, they tried to identify not only when the courier had started working but if they intended to work into the foreseeable future. They regularly followed up with couriers and charted those who said they had not worked in a while or did not intend to work again. When someone said their account had been deactivated, they charted this in a separate “deactivated list” (Figure 3), so they had the names of the likely candidates with which Foodora might stack the list. In all of these cases, they tried to chart the date of the last shift worked.

Tracking co-workers’ levels of engagement in the campaign is important for any charting, but in these circumstances, if a courier had not attended a meeting in a while, this might also mean they no longer worked for Foodora.92 The Foodsters would prioritize them in their follow-up. They also made sure to call couriers, not just email them, because if their number was no longer in service, they had likely left Foodora, since the account was tied to the phone number.93

The campaign acquired this information in various ways. Much of it came through organizing conversations and regular follow-up. The Foodsters also scoured any Foodora-related social media groups and chats and took advantage of the company’s mistakes. For example, in one of the newsletters the company periodically emailed to couriers, Foodora accidentally put over 500 couriers’ email addresses in the carbon copy section instead of blind carbon copy, essentially handing these email addresses to the Foodsters.

Figure 3. The deactivated list.

The Foodsters’ extensive, almost obsessive, mapping and charting might appear a bit like Borges’ peculiar Cartographers Guild, in which “the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province.”94 But it proved indispensable for the most dramatic month of the entire campaign.

July 2019

The Foodsters had originally planned to apply for certification in August 2019, because in September, with the influx of college and university students, courier turnover would be high. In May, the Foodsters had estimated that there were 800 Foodora couriers. By July, however, they had acquired a critical mass of courier names and contact information. They now estimated that the number of people with active courier accounts, including those who had not worked in several months, was more than 1,000.95

In early July, Foodsters United launched a phone-banking, card-signing blitz – “probably the single biggest undertaking of the campaign.”96 cupw booked off members who spoke the languages the Foodsters had identified in their mapping and charting, including Punjabi, Hindi, Arabic, and Spanish. Thomas remembers particularly well a call with a West African courier, because they were struggling to understand each other.97 Thomas tried explaining the union but could tell the courier wanted to hang up. Thinking quickly, when Thomas asked if the conversation would work better in another language, the courier replied, “French.” As Thomas recounts, “My buddy Richard, who speaks French, was sitting right beside me. He was about to dial a new call, but I put my hand on his and said, ‘One second, brother.’ I passed the phone over to Richard and there was this rapid conversation in French, but after a few seconds, I could hear, ‘Oui! Oui! Un syndicat! Un syndicat!’” When someone agreed to sign a card, the Foodsters dispatched a courier to ride or drive to them wherever they were in the city – an advantage of this kind of workforce. Nevertheless, Foodora staged a counterattack.

In mid-July, bright pink billboards began appearing all over the city: Foodora had launched a massive hiring spree. Although they had told couriers they would wait until September, when demand would increase again, they started hiring sooner, which would increase the employee list. This is much easier in the gig economy, where, given the reliance on casual labour, companies can hire people without guaranteeing them many shifts. The Foodsters, caught off guard, regrouped quickly and announced a new chokepoint. On 23 July, they set up outside of Foodora’s King Street office so that they could have organizing conversations with newly hired couriers arriving for their orientation. Whether the Foodsters caught them entering or exiting the office, most of them signed cards right then and there, many of them before they had attended their orientation.

Foodora, however, was not done yet. On 26 July, the Foodsters discovered that Foodora would be reactivating hundreds of deactivated courier accounts, further inflating its employee list. “They probably set a line for themselves, ‘Well, we can’t invent people, but we can bring couriers back from the dead.’”98 Foodora had sent an email to numerous deactivated couriers, informing them that they would be reactivated on 5 August. The Foodsters were unsure how many would be reactivated. They contacted the people on their deactivated list to find out how many had received the surprise reactivation email. They asked those who would be reactivated to either delete the app or sign a union card, which many of them did.

At this point, Foodsters United was confronted with a major decision. Typically, when a union applies to certify, they want to exceed by a comfortable margin the 40 per cent threshold for signed union cards. Although they had signed more cards in July than any other month, Foodora had also hired extensively. The Foodsters estimated that their 452 signed cards still represented only 35 per cent to 40 per cent of all the couriers with an active Foodora account. Even if they signed dozens of cards in the coming weeks, they were not sure they could keep pace with Foodora’s hiring spree. In the gig economy, especially, it is much easier to hire many people than it is to find them and persuade them to sign union cards. Furthermore, there loomed the mass reactivations on 5 August.

The Foodsters thought that if they could argue successfully to the olrb that an active worker was a courier who had worked within a certain cutoff date, then the battle would become one of percentages. If the olrb ruled that the cutoff was within the year, Foodora would have to remove some of the older names from its employee list, but the Foodsters would also lose some of the older cards they had signed. The more recent the cutoff date, the fewer the names either side could claim. “It sucks,” Scott Shelley notes, “because we bled for those cards.”99 Even if, as things stood, they only had around 35 to 40 per cent of cards signed, they calculated that Foodora was likely to lose more names than the Foodsters would cards, and as the number of names on Foodora’s employee list dropped faster than the number of cards, that figure would inch closer to 40 per cent and eventually surpass it. Based on their extensive charting, the Foodsters could estimate the respective percentages for each cutoff date down to the month. If the olrb deemed as active workers anyone who had worked a shift within six months of their application to certify, the Foodsters had enough union cards to meet the 40 per cent threshold.100

The Foodsters were not certain as to what the olrb would decide, but they thought this was the closest they could get before the mass reactivations in August and the major turnover in September. With nervous excitement, Foodsters United applied to certify on 31 July 2019. Then, around fifteen Foodsters made their most important delivery yet. Jubilantly, they handed the application to David Albert, the stunned managing director of Foodora Canada.101

The union vote

Foodora challenged the application to certify, claiming that the couriers, as independent contractors, had no right to unionize. The olrb ruled that because of the decentralized workplace, the union vote would take place online from 9 to 13 August 2019, but that the ballots would remain sealed pending two other rulings. The labour board would hold hearings to decide the classification of Foodora couriers, and if it was determined that they are employees with the right to unionize, then there would be status dispute hearings to determine who would be considered active workers. Based on that ruling, the olrb would count the union cards signed by active workers, and if the Foodsters met the 40 per cent threshold, the board would unseal and count the ballots of active workers for the union vote.

In the meantime, Foodsters United began planning actions for the upcoming classification hearings and continued their outreach, mapping, and charting. Nevertheless, the end of the all-consuming card-signing phase of the campaign gave the Foodsters more time to reflect on what they were doing well and what they needed to improve. This included organizing strategies like leader identification, issue identification, and the structure of the campaign itself.

Leader Identification

We were always saying, “There’s too much work and not enough people to do it. We need to identify new leaders, bring them in, and build them up.” The problem is, that is also work.

Sometimes the stuff that was right in front of us would take precedence, so we were always playing catch up. We all recognized that, but long after we should

have.

—Alex Kurth

At the beginning of an alley cat race, each participant is given a “manifest,” the map of all the checkpoints they must visit before finishing the race. Alex notes that novice racers often make the mistake of starting the race before they have carefully planned their route: “People will have a moment of panic and say, ‘Oh! We need to go! We need to go!’”102 Union drives can be like this, especially with one organizing method in particular: leadership identification. “That was one of our biggest weaknesses,” Iván notes.103 Although they did not explicitly state this at the time, “As the campaign got rolling, we were going places without having done much leadership identification, which made it less of a priority, because we thought, ‘We’re still going somewhere, we don’t want to stop or go backwards in a campaign.’”104 When there are so many tasks and so little time, sometimes the initial organizers start doing them immediately, not strategically. Instead of taking time to identify and develop others who can also do these tasks, the tasks get done by those who already know how. In the end, instead of saving time, you lose it – as well as a great many other things. With respect to this parallel between alley cats and union drives, Iván notes, “It’s a brain thing, not a legs thing. That’s what I always said to those guys who just book it. ‘No, no, no, it’s not a legs day today.’”105

Leader identification is crucial for workplace organizing.106 Every workplace has leaders. They are not necessarily the workers with formal positions. They usually do not speak first or loudest. But when they do speak, others listen. What they say about the union drive can make it or break it. Leadership identification is a method for understanding the qualities of these organic leaders and determining who has them. A small group of organizers can try speaking one-on-one with every single co-worker, but this makes for an inefficient race, especially in a large workplace. If the organizers identify the leaders in each of the organic groups, however, they can speak to these leaders, who can then not only speak to everyone in their respective groups but do so more persuasively than the organizers. Numerous core organizers felt they had learned this too far into the race, but they improved as they went along.107

Early in the campaign, the Foodsters’ idea of a leader was the veteran bike messengers who were influential in the downtown courier community. They did have some of the qualities of a leader. They were very good at their jobs and could bring people together by organizing alley cats and volunteering at the checkpoints. Most importantly, however, besides Foodora itself, they were the most anti-union group.108 It was not that all, or even most, of these veteran couriers opposed the union, but those who did were unified and vocal. Some deemed unions incompatible with the independence that pervades the messenger ethos.109 Some of the older messengers had also experienced cupw’s prior failed attempt to unionize. Toronto bike couriers had certified federally as cupw Local 104 in 2011, but then the federal court ruled they should be regulated provincially.110 Their third attempt at certification in Ontario was successful in 2012, but these couriers, working for Quick Messenger Service, failed to achieve a first contract. After significant turnover, a group of new couriers with less connection to the union voted to decertify in 2015.111

The Foodsters attempted to either persuade or neutralize these veteran messengers by workshopping answers to their arguments.112 They honed their answers to tough questions by following the classic framework of affirming, answering, and redirecting. For example, the Foodsters might respond that they understand how, for an experienced courier, app-based food deliveries can pay better than more traditional paper deliveries (affirm), but the pay is declining (answer), and even if it were not, there is nothing wrong with fighting for better pay, which a union can help to do (redirect). By persuading some of these veteran couriers while shifting some of the most hostile toward indifference, the Foodsters were able to increase their support in the downtown courier community.113

The Foodsters soon realized, however, that they had overestimated the influence of these veteran messengers as much as that of the messenger community.114 As the Foodsters expanded their outreach to the broader Foodora workforce, they found it difficult to identify co-workers, let alone leaders. When they found out that Chinese and Brazilian couriers had each set up group chats, the Foodsters got one or two people from each to sign cards but did not reach either group as a whole.115 The campaign was not yet able to train these individuals, their sole points of contact for these groups, to do their own leader identification.

The campaign began developing these skills more concertedly in the fall of 2019, when cupw staff organizer Liisa Schofield brought a group of couriers to weekly trainings by the influential organizer and writer Jane McAlevey. McAlevey’s revival of industrial organizing methods has achieved significant victories. For example, her campaigns with Nevada nurses used “big representative bargaining,” in which 100 rank-and-file nurses routinely participated in contract negotiations. This reinvigorated the union and won their demands on wages, employer-paid family health benefits, and nurse-patient ratios.116 McAlevey argues that the labour movement has suffered major defeats because it prioritizes two approaches.117 The first is advocacy, which is done by a small minority of people – representatives, lawyers, researchers – on behalf of the majority. The second is mobilizing, which encourages larger numbers of people to act on their own behalf, but they tend to be the activists who are already committed to the cause, and their participation is limited to one-time events, not the overall strategizing and planning. McAlevey attributes the rare successes of a few recent campaigns to a third approach, deep organizing, which replaces backroom deals with mass negotiations: “Ordinary people help make the power analysis, design the strategy, and achieve the outcome. They are essential and they know it.”118

McAlevey’s organizing trainings included leadership identification. “That became important,” Thomas notes, “looking for folks whose words matter.”119 For example, a few organizers discovered when speaking with Filipino couriers that they would often say, “I have to ask Jacob first.”120 Jacob was a migrant worker who spoke Tagalog and English and had been a courier for a few years. Indeed, he had many of the qualities that organizers learn to identify in a leader. For example, co-workers would ask Jacob the questions they were too embarrassed to ask anyone else.

The Foodsters made an effort to connect with Jacob. Thomas notes, “I came to him and said, ‘Jacob, I don’t know if you know this, but a number of people really respect your opinion.’” Jacob downplayed his influence: “He said, ‘I just try to answer questions for people. I come from the Philippines, so I try to help other people from the Philippines.’” Nevertheless, Thomas continues, “He was someone people trusted to guide them through various situations.”121 A question Jacob often received from Filipino newcomers was “Can I trust these people?” Once he was persuaded that the union was a good idea, Jacob could say yes to co-workers in a way that made them feel safe.

Even here, though, the results were mixed. Although Jacob signed a union card and persuaded other Filipino couriers to do so, he did not get more deeply involved: “He was always a little bit aloof from us.” As Thomas notes, “One of the problems that McAlevey identifies is that often leaders aren’t interested in the union because they don’t need the union.” Jacob rode an e-bike and had bought two batteries so that he could switch them mid-delivery. He was getting shifts. He also had a network of people who looked up to him as a natural leader. “You add onto that the valences of migration status, overwork, and distrust of certain communities,” Thomas continues, “there’s a lot of reasons that leaders are going to stay peripheral to the work.”122 Indeed, Jacob lived in Scarborough, commuted to the downtown core, and worked 60 hours a week.

While the Foodsters could apply traditional leadership identification in cases like these, they also had to adapt it to a workforce that was very large, decentralized, and subject to rapid turnover. Liisa refers to questions the couriers discussed while attending McAlevey’s trainings: “How do you use these kinds of tools when your list of workers changes every 30 days?”123 They found they needed to embrace some of the community organizing methods that McAlevey criticizes.

For McAlevey, organizing is “structure based” when it occurs in bounded spaces – such as workplaces or churches, which have specific numbers of people – so the organizers know how many supporters are required to get supermajorities over 90 per cent.124 This requires organizers to reach everyone in this space, not just those who already agree with them. Even if a small group of organizers could do this alone, they could not do it effectively, so they must identify pre-existing leaders. Since these leaders might not agree with them, organizers must learn how to persuade them through organizing conversations that show how their interests are tied to those of the collectivity. For example, as individuals, they might get better shifts but not a pension.125

When organizing is not structure based, there is less pressure to reach everyone, because who this is, and what would count as a supermajority, is less clear.126 Organizers will tend to speak to people with whom they already agree. This can foster groups of “self-selecting” activists who join because of pre-existing interests or commitments but not supermajority organizations comprising many people who had never considered themselves activists before. McAlevey thinks that self-selecting groups exist throughout various kinds of movements, including the labour movement, but it is especially prominent in community organizing. These groups often speak of leader development rather than leader identification, because they try to develop leaders among the non-leaders whom they already know and agree with. They do not identify existing leaders, which requires going beyond their comfortable group and persuading people who might currently disagree with them.

Liisa contends, however, that decentralized workforces subject to immense turnover, such as gig workers, need to combine leader identification with a kind of leader development.127 A significant number of couriers did not know any other couriers, which stifled the development of organic communities and leaders.128 The Foodsters found that for the most isolated couriers, before they could identify leaders they first had to create the conditions in which leaders could emerge. When they introduced a courier to the campaign, they would train them to do organizing conversations. “Then you go into the field with them,” Liisa notes, “and see how they do, debrief with them, see how they do again, debrief again, and keep going until you see some really brilliant people emerge.”129 By giving workers various responsibilities and seeing who resonates with people in an unusual way, you not only identify the leaders whose words matter but develop and identify the workers whose words will matter.

Issue Identification

To be honest, those demands meetings didn’t accomplish much, except to reinforce the issues we had already come up with. We spent a lot of time fishing for as many problems as we could,

rather than having some discussions on what was actually achievable.

—Eliot Rossi

The Foodsters had discovered the many different issues that most concerned their co-workers through organizing conversations and their well-attended “demands meetings.” Nevertheless, the campaign had not yet identified their main issues. Prior to the classification hearings, which began in September 2019, organizers had joined couriers in the Foodora office to resolve issues like arbitrary deactivations or had submitted demands to management after a few cases of workplace harassment.130 But the campaign had not yet identified a majority issue and made a formal demand to Foodora. Without this, it can be hard for a campaign to claim credit for improvements achieved by their activities.

After Foodsters United went public, Foodora improved its app.131 For example, the button to decline orders suddenly began working. This was a direct result of the union drive, but achieving such improvements is only half the battle. A campaign also has to “name it and claim it,” which means framing what has been achieved and who is responsible. Otherwise, the employer will do so. For much of the workforce, the broader public, and posterity, it will be not a functional improvement to working conditions provoked by workers’ collective pressure but an initiative of the company undertaken in consultation with its independent contractors. It is easier to name it and claim it when it has resulted from an issue that has been identified and turned into a formal demand. “We weren’t good at that,” Iván notes. “That change only happened in the heat of the union drive. We should have said, ‘You think that change happened coincidentally?’”132

Foodora also introduced such changes because of the impending classification hearings. An app that gave more control to couriers supported Foodora’s argument that they are independent contractors. The Foodsters knew that legal proceedings undertaken by small teams of representatives can disengage rank-and-file workers. They encouraged couriers to attend the hearings by, for example, creating custom-made bingo cards, which brought both levity and inoculation into the often tedious proceedings (Figure 4).

At each of the hearings they held rallies, served coffee and food, and, for the December hearing, sang holiday carols outside of the Foodora office before delivering a box of coal.133 These efforts were quite successful: “The Ontario Labour Relations Board said they had never seen so many workers show up for a hearing before.”134 Nevertheless, the Foodsters needed an action that could inspire majority participation during this legal phase of the campaign. This required identifying an issue and a demand that inspired widespread enthusiasm. The right issue is not necessarily the employer’s most egregious activities, nor even the most illegal; rather, the right issue is widely felt, deeply felt, and winnable.135 Winnability is particularly important early in a campaign and among workers without much organizing experience, because getting an early victory, even a small one, builds confidence to aspire for more.

For some couriers, their treatment by the dispatchers was deeply felt – they resented it intensely. But it was not widely felt, because other couriers appreciated the human element of Foodora’s dispatch system, in contrast to the impersonal Uber Eats app based entirely on algorithms.136 Conversely, tips were a widely felt issue. Foodora’s tipping system allowed customers to tip when they ordered food but not after it had been delivered.137 Nevertheless, since this provoked annoyance, even exasperation, but not indignation, it was not deeply felt. The inadequate urban infrastructures and traffic congestion are felt deeply and widely but are not winnable, because they yield no demands the employer can easily meet. There was one issue, however, that was widely and deeply felt and could be addressed with relatively simple changes to the app’s coding: “automatic compensation.” The Foodsters had identified their issue.

According to Foodora’s contract, whenever couriers had to wait more than twenty minutes at a restaurant for their order, they were entitled to compensation of five dollars. Nevertheless, this had to be requested manually and Foodora was not informing new hires about this part of the contract, so most of them did not know it existed. “You can call it wage-theft by negligence.”138 The Foodsters formulated their demand: they wanted automatic compensation, or “auto-comp,” a timer built into the app that began when they arrived at a restaurant. If the timer exceeded twenty minutes, they would automatically receive the five dollars stipulated in the contract.

Figure 4. A classification hearing bingo card.

They had formulated their issue into a demand easily understood by everyone. It was a majority demand, because every courier with whom they spoke wanted it when they heard about it. It was relatively easy for Foodora to give, because it required only basic changes to the software and would not set a new precedent like a wage increase. “How could they refuse to give couriers what they promised already in the contract?”139 They also identified the appropriate target, the people with the authority to meet the demand. They would issue this demand to David Albert, managing director of Foodora Canada. If he refused, the couriers could use that for further agitation and would escalate their tactics. If he met the demand, it proved that couriers could provoke improvements to their working conditions, which opens the door to further demands. If they used the smaller victories to move gradually toward bigger victories, it would make the conversations about much more ambitious demands, like improving bike infrastructure, more plausible.140

The Foodsters now had their issue, demand, and target. What they did with them would be their most ambitious endeavour since the card-signing blitz in July.

The petition drive

In February 2019, the Foodsters decided to turn the auto-comp demand into a majority petition. They would do both street and phone outreach with couriers, but it was a physical petition that had to be signed manually by pen.141 This made it more difficult to get signatures than it would be with an online petition, but getting signatures was only a means. It meant that couriers could only sign the petition after having one-on-one conversations with organizers.

The Foodsters’ goal was to encourage majority participation during the legal phase, because the auto-comp demand was more tangible than the misclassification issue and the petition was more exciting than the hearings.142 They wanted 90 per cent of Foodora couriers to sign, but because of the hiring spree and turnover since July, they did not know the size of the fleet. Therefore, they wanted not only to reconnect with the couriers they had met during the card-signing phase but also to bring into the campaign all of the new hires who would benefit most from auto-comp.143 They would focus petition outreach where Foodora had recently expanded, such as in Mississauga and Brampton, where the Foodsters had few connections. It allowed the Foodsters to continue their extensive mapping and charting of who among those with Foodora accounts was actively working: “It was good for us to establish who is actually going to be in this local.”144

They created a dispatch system. Each organizer had a tablet, and when a courier agreed to sign the petition, the organizer used an “Alert Team Lead” button to immediately send the relevant information to their dispatchers.145 The alert would include the courier’s name, their location, and when they were available to sign. The dispatcher could then send someone by bike or car to deliver the petition.

The Foodsters had an additional goal for the petition. For the couriers who attended the McAlevey workshops, the idea of “structure tests” resonated even more than leader identification.146 These are a series of actions that gradually escalate in terms of commitment, risk, and ability to pressure the employer, by which organizers can assess their organization as they build it.147 The campaign begins with an action requiring lower risk and commitment, like signing a petition, and if a supermajority signs, the organizers can pass to the next structure test. If not, they assess where to improve. For example, if some of the workers identified as leaders were unable to get most of their work group to sign, more leader identification is needed before trying this structure test again. Organizing is, in many ways, a series of structure tests that culminates in the ultimate such test: a strike that can halt production. The Foodsters began with a petition to confirm the leaders they had identified and to provide opportunities for new leaders to emerge.

The organizers also had an outline of how they would deliver the petitions.148 They would photocopy the originals and combine them into a large board.149 They would then deliver the board to Albert at the Foodora office in a “march on the boss” action. This would fulfill the essential parts of a direct action. Along with their issue, demand, and target, the action – however nerve-wracking for the participants – would also be fun and visible, because the more couriers who participated, the better. A few couriers could be prepared to give brief testimonials to their boss about the importance of this demand. If they are not the better-known organizers of the campaign, that is better, and if they are good workers respected by management, better still, because it demonstrates that this is a majority demand that is widely and deeply felt. A few of the other participants could act as moderators, interjecting only when the boss tries to interrupt or dissemble, and reopen the space for the testimonials. The demand would then be made formally and “issued on a timeline,” the deadline by which the boss must meet the demand. Against the boss’s likely attempts to defer indefinitely, this would give the workers a date by which they would know whether or not they have won. In this petition drive, Foodora would be given one month. If the demand is not met by the deadline, they should already have a plan to escalate with actions that increase the pressure on their boss.

As the petition drive began, the campaign was further bolstered on 25 February 2020, when the olrb ruled that Foodora couriers are dependent contractors, a form of employee with the right to unionize. According to the ruling, “The courier is a cog in the economic wheel – an integrated component to the financial transaction. This is a relationship that is more often seen with employees rather than independent contractors.”150 Now there would be hearings to determine who would be considered an active worker and whether the Foodsters had sufficient union cards and votes to certify. With the wind at their backs, the Foodsters rode into the petition drive. Most of the couriers with whom they spoke were signing the petition.151 In the first two weeks, they got more than 500 signatures. They seemed to be passing the structure test. But then, the covid-19 pandemic hit. The majority petition would soon be put on hold as Foodsters United went into crisis mode.

The COVID-19 pandemic

As the pandemic spread across the world, the first lockdown measures in Toronto began in March 2020. Suddenly, the demand for food delivery was much higher.152 The pay and tips were better than usual, but there was also much uncertainty about the virus and how it spread.

When Foodora ignored demands to provide personal protective equipment and a no-contact delivery option, the Foodsters organized members with sewing machines to craft fabric masks. They delivered these masks through their newly formed covid-19 Care Committee. This was one of a few committees they created during the pandemic, including a resources and education committee, which collected and distributed information useful for front-line workers; an outreach committee, which connected and met with workers to discuss their concerns; and, an action committee, which coordinated actions to gain public attention and pressure the company and government. The latter, as part of a broader cupw pressure campaign on the federal government, likely helped to make the Canada Emergency Response Benefit more accessible to gig workers.153 Nevertheless, responding to the pandemic required immense effort, which interrupted not only the petition drive but also the Foodsters’ plans to introduce more formal structures in the campaign.

Structure

You would think that, organically, people that wanted to organize with us would come to us. We found out that wasn’t the case. For whatever reason, the psychology inherent in this kind of

thing, if you’re not in there from the beginning, people have this idea that things are already taken care of, every slot is already filled … It was a constant struggle to find more people and elevate

them to leadership positions.

—Scott Shelley

Foodsters United was more democratic and participatory than most union drives. Nevertheless, though the core organizers agreed on the need for democratic structures, there were substantive debates and disagreements about what that meant in these challenging circumstances.154 The campaign had introduced voting procedures and minute-taking, but in retrospect, whatever their other disagreements, there is consensus that more formal structures should have been implemented earlier, including bylaws and elections.155 As Chris notes, “We kind of had an Occupy Wall Street issue.”156

These structural problems were exacerbated by the challenges of organizing in the gig economy. Gig workers face a lengthy period between the start of the campaign and certification, especially when they have to challenge their misclassification.157 The core group of organizers, the inside committee, cannot rely on impending certification to establish bylaws and hold elections. Keeping this inside committee accountable not only to one another but to their co-workers, the future members of the union, requires formal structures and procedures to be in place long before certification. This is also crucial for sustaining widespread interest and participation in the drive amid so much turnover.