Labour / Le Travail

Issue 90 (2022)

Article

“They Will Crack Heads When the Communist Line Is Expounded”: Anti-Communist Violence in Cold War Canada

Abstract: This article examines anti-communist political violence in Canada during the early years of the Cold War. It specifically focuses on the Ukrainian Canadian community, one of the country’s most politically engaged and divided ethnic groups. While connected to an existing split within the community, acts of violence were largely committed by newly arrived displaced persons who were much more radical than existing anti-communist Ukrainian Canadians. Government and state officials tacitly, and sometimes even explicitly, sided with the perpetrators. This laxity toward the violence reveals how, in the early years of the Cold War, law and justice were mutable and unevenly enforced depending on the political orientation of those involved. In a broader sense, this article adds to an understanding of the multifaceted ways that anti-communism manifested itself in this period to define the acceptable parameters of political consciousness.

Keywords: violence, Cold War, communism, anti-communism, law, political policing, ethnicity, migration, Canada, Ukraine

Résumé : Cet article examine la violence politique anticommuniste au Canada pendant les premières années de la guerre froide. Il se concentre spécifiquement sur la communauté ukrainienne canadienne, l’un des groupes ethniques les plus engagés politiquement et les plus divisés du pays. Bien qu’ils soient liés à une scission existante au sein de la communauté, les actes de violence ont été en grande partie commis par des personnes déplacées nouvellement arrivées qui étaient beaucoup plus radicales que les Ukrainiens canadiens anticommunistes existants. Les représentants du gouvernement et de l’État ont tacitement, et parfois même explicitement, pris le parti des auteurs. Ce laxisme envers la violence révèle comment, dans les premières années de la guerre froide, le droit et la justice étaient variables et appliqués de manière inégale en fonction de l’orientation politique des personnes impliquées. Dans un sens plus large, cet article contribue à une compréhension de les manières multiformes dont l’anticommunisme s’est manifesté à cette époque pour définir les paramètres acceptables de la conscience politiques.

Mots clefs : violence, guerre froide, communisme, anticommunisme, droit, maintien de l’ordre et politique, ethnicité, migration, Canada, Ukraine

On the evening of 8 October 1950, fourteen-year-old Nina Breshko attended a Thanksgiving weekend dance at the Ukrainian Labour Temple in Toronto, Ontario. Just before nine o’clock, a bomb exploded. Shattered glass and shrapnel filled the hall and many, including Breshko, were wounded. The bombing was not an isolated incident but rather part of a concentrated campaign of violence directed against members of the pro-communist Association of United Ukrainian Canadians (auuc) by recently arrived Ukrainian displaced persons (dps).1 Including a range of violent acts – intimidation, vandalism, attempted kidnapping, and grievous assaults – this crusade spread across the country wherever the auuc had a visible presence. It had serious consequences for its victims, but few – if any – for its perpetrators. This was because their political goals, if not their tactics, were bolstered by existing right-wing Ukrainian organizations in Canada and condoned by agents of the state for whom anti-communism took priority over the enforcement of the law.

The pivotal role of violence in community building remains understudied in Ukrainian Canadian historiography. To some degree, this reticence is influenced by the myth of Canada as a peaceable kingdom. Within this paradigm, political violence is cast as an aberration from an otherwise rational society.2 As a result, scholars of the Ukrainian Canadian experience tend to portray violent incidents as extraneous to community building rather than as an integral component of it. Confrontations between warring factions are recounted as if they were the consequences of a few agitators getting carried away in defence of strongly held opinions, in instances where cooler heads could not maintain order.3 Yet, as H. L. Nieburg contends, violence is “a natural form of political behaviour [that] cannot be dismissed as erratic, exceptional, and meaningless.” Viewing violence as separate from other social actions effaces the continuum between what is deemed orderly and disorderly. Moreover, it denies how violence both creates the terms of social bargaining and tests political legitimacy.4

This episodic view of violence is also correlated with the production and maintenance of anti-communist hegemony within the community – a hegemony that has shaped the historiography. From this perspective, even when violence is explored in more detail, obvious lines of inquiry have gone uninvestigated, the moral righteousness of preferred actors is assumed, and its broader consequences are essentially ignored.5

From the pitched battles between the Orange and Green Irish throughout much of the 19th century to the Air India bombing at the end of the 20th century, historians of Canada have paid much more attention to violence within or between ethnic/migrant groups. By and large, this has been approached from three distinct, yet interrelated, vantage points. The first addresses violence directed toward migrants as well as the xenophobic and racist rhetoric that shaped their lives.6 The second situates violence within intersectional histories of labour, ethnicity, and gender.7 Violence toward migrant women, usually committed by their spouses, is especially well documented.8 Lastly, historians have examined public displays of violent spectacle, highlighting how migrants have participated in collective action to spur important social, political, and economic change.9

Of the violence under review in this article, a few distinctions can be noted. First, the violence was rarely spontaneous but rather carefully orchestrated. Second, while connected to an existing political divide within the Ukrainian community, it was largely committed by a group of new arrivals whose tactics and ideology were more radical than the extant right-wing Ukrainians with whom they allied. By the late 1940s, the intensity of the dps’ anti-communism was connected to a discourse of lost war revanchism. When the realization of an independent Ukraine was eliminated by the solidification of Soviet rule, solving the communist problem in Canada became an acceptable consolation prize. In their attacks on auuc members, the dps believed themselves to be contributing to the global fight against communism. Third, the Canadian state tacitly and sometimes even explicitly sided with the perpetrators. On the one hand, this complicity is in line with the state’s efforts to select and support politically useful migrants. On the other, “Canadianization” programs aimed at dps were ostensibly designed to pacify and acculturate those with considerable experience of violence during World War II.10 Apparently, some newcomer violence was acceptable in Canada, provided that it was directed against communists.11

While Ukrainians had been migrating to Canada since the late 19th century, a perceptible political divide did not appear until the early 20th century. Several factors, including the transfer of Old World ideology by transnational migrants and domestic conditions that bred political radicalization, were responsible for the eventual development of a distinctive left and right. Ukrainian leftists initially congregated in chytalni (reading clubs) and enlightenment societies as well as in more formal institutions like the Ukrainian branches of the Socialist Party of Canada and the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party (usdp).12 In 1918, following the outlawing of the usdp during the First Red Scare, which included the internment of many Ukrainian leftists, the Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association (ulfta) was born.13 In 1921, the ulfta aligned itself as a language-federation of the Communist Party of Canada (cpc).14 An example of what others have described as hall socialism, the ulfta’s Labour Temples were the lifeblood of the Ukrainian left, aiding its constituents in every facet of their lives.15 This ability to be both a sociocultural outlet and a vessel for radical change served the association well. By the time it had renamed itself as the auuc in response to another wave of repression during World War II, it enjoyed significant popularity as indicated by its approximately 15,000 card-carrying members.16

The roots of the Ukrainian right can similarly be found in chytalni and enlightenment societies, as well as in the churches (both Catholic and Greek Orthodox).17 These spaces were shared by natsionalisty (nationalists) and narodovtsi (populists) who, as Orest Martynowych notes, “had at best a passive interest in Ukrainian affairs overseas [and] little if any affinity for nationalist … politics.”18 Despite Anglo-Canadian sources often conflating these positions, a distinction should be drawn.19 To be sure, both the nationalists and the populists supported the creation of an independent Ukrainian state and, in Canada, promoted Ukrainian language, literature, and culture. But by the interwar period, in the aftermath of Ukraine’s various unsuccessful battles for independence, the populists began to distance themselves from the nationalists, whose politics were increasingly reactionary.20 Many nationalists now endorsed a culture of Völkisch-ness, martial worship, strict religious adherence, corporatism, common language, and hierarchies of race, class, and gender. In Europe, the largest organizational manifestation of such politics was the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (oun).21

Once in Canada, followers of the oun, and adherents of these politics more generally, were concentrated in the Ukrainian National Federation (unf).22 Established in 1932, by 1939 the unf had approximately 7,000 members.23 In 1940, the federation became the largest constituent group of the Ukrainian Canadian Committee (ucc), an umbrella organization for all non-communist Ukrainians.24 The ucc was formed because of the government’s growing concerns that the community, and its existing organizations, would prove disloyal to the Allied cause.25 In addition to giving the government direct access to Ukrainians and their affairs, the ucc would serve as a vigilant watchdog against communism.26 This was only made easier when, between the end of World War II and 1952, the committee’s ranks were strengthened by the arrival of some 35,000 to 50,000 dps.27

The ucc and its constituents wholeheartedly supported the admittance of dps to Canada. Among the many hopeful migrants were members of their own extended families who had not been able to cross the Atlantic before the war broke out. Helping them settle, then, was a moral obligation and a way to assuage survivor’s guilt.28 For the government, in addition to filling labour shortages, the dps could effectively broadcast their anti-communist sentiments to the public. Julia Lalande demonstrates how, in its advocacy, the ucc consistently framed this as an asset. In a petition submitted to the government urging the approval of dp resettlement, the committee noted that they had “displayed their skill in organizational and constructive work. These displaced persons if assisted to settle in Canada would spearhead the movement and combat communism since they are victims of its menace.”29

Vocal in opposition to the dps were members of the auuc who indiscriminately, and with very little concrete evidence, branded them all as fascists and collaborators.30 They further promoted the xenophobic trope that the dps would take jobs from Canadians. Their opposition was largely ignored by state officials and had very little sway with the public.31

The first point of contact between dps and members of the auuc was usually on train station platforms as the former left for the hinterlands of Ontario and Québec to fulfill labour contracts. Despite their misgivings about the political character of the dps, auuc organizers initially tried to recruit them into communist-backed unions, hoping that this might reorient them toward Canadian conditions.32 These efforts were largely in vain. In Timmins, Ontario, 59 dps bound for the Hollinger Consolidated Gold Mines declared the presence of two communist organizers on their train as being “no good” before beating them and tossing them off at the next stop.33

Such stories were relatively common and precipitated a return of hostility from the communists, who now vowed to fight back. “Hitlerites, fascists, gangsters, and so on,” described the editor of the auuc’s newspaper, Ukrainske zhyttia, “are getting down to business: the cracking of heads of Canadian workers. After this we can expect from them strike-breaking, informing, and smashing of trade unions.” The only solution was to isolate dps in the camps “like a contagion,” treating them “as if they carried a sign declaring them as fascists.”34 Soon after, rcmp officers stationed across the country reported case after case of communist antagonism toward the dps. In Wakaw, Saskatchewan, members of the auuc stormed a dp meeting and accused their speaker of working for the Polish police and of having a Blutgruppentätowierung (Waffen-SS blood group tattoo).35 In Trial Lake, Ontario, dps clashed with their communist bunkmates who had tauntingly hung a portrait of Joseph Stalin on their bunkhouse wall.36 Meanwhile, in Hornepayne, Ontario, fourteen communists, including some non-Ukrainians, were arrested after beating up a group of dps in their work camp.37

The ongoing offensives greatly alarmed the ucc. In consultation with its contacts in the government, the committee personally petitioned Prime Minister Mackenzie King to intervene.38 The issue was fresh on King’s mind; anxious employers were already drawing his attention to the situation. Eager to rid themselves of the communist-led unions in their camps, they described the clashes as being triggered by embarrassed Reds whose lies about the Soviet Union were finally being exposed.39 King looked for guidance from Arthur MacNamara, deputy minister of labour, and Department of Labour (dol) bureaucrat John Sharrer. Sharrer, who had been intimately involved in the process of recruiting dps to Canada, confirmed the narrative of the bosses: the dps were victims of unprovoked communist belligerence.

What could be done? Communist-led unions, such as the Congress of Industrial Organizations (cio), and left-wing political organizations were legal in Canada. While it would be improper for government officials to openly involve themselves, Sharrer believed that something much more covert was possible if employers, the rcmp, and their Ukrainian contacts were willing to quietly collaborate.40

Sharrer’s plan was multifaceted. Through citizenship classes facilitated with the help of the dol, employers would propagate the bountiful privileges of Western democracy and attempt to dissuade their workers from the unhealthy political influence of communism.41 rcmp officers would open covert channels of communication with dps to prevent unnecessary interactions with auuc or cio members and to agitate against them whenever possible. Stuart Wood, acting commissioner of the rcmp, believed that this would require very little actual work. “Many of these dps are brilliant men,” he reported, “who do not want any more of communism and are very thankful to be in Canada.”42

Volunteers from the ucc were tasked with greeting dps at ports and platforms to prepare them for what greeted them in the hinterland. Members of the unf, whose politics most closely aligned with those of the dps, were specifically sent to the camps as handlers. Among their tasks was talking disgruntled dps out of joining strikes and personally grieving their concerns before their bosses.43 They also negotiated for separate bunkhouses, frequent visits by priests, and a steady stream of social activities to keep the dps busy.44 Working in the camps alongside the unf were John Hladun and Danylo Lobay, former members of the ulfta who had left the association in the 1930s over concerning developments in Soviet Ukraine.45 The men, whom the rcmp referred to as their secret weapon, wrote and distributed anti-communist literature, delivered lectures, and persuaded dps to join government-vetted unions that were seen as bulwarks against Red Unions.46

Supporters of the oun were also active. Beginning in 1946, the organization established a clandestine network in Canada under the direction of Stanley Frolick, a lawyer and community activist.47 Frolick was known to propagate anti-communism and the ideology of the oun in the camps, although it is unclear whether such efforts were sanctioned by the government.48

Canada’s professional class of Cold Warriors, who had been quietly working with Ukrainian nationalist outfits on behalf of the government since the late 1930s, further assisted in Sharrer’s scheme.49 Watson Kirkconnell, a professor at Acadia University, facilitated the publication of a series of newspaper articles reinforcing the position that dps posed the strongest threat to communism. “Stalin was mistaken if he thought dps would swell the ranks of his fifth column in this country,” one such editorial in the Globe and Mail remarked. “They laugh bitterly when Canadian grown Reds try to sell them a bill of goods [because] they know too much and will not swallow the propaganda pill easily.” In the future, the editorial warned, “they will crack heads when the communist line is expounded.”50

auuc leadership now recognized that they could neither win the dps over nor persuade the government to return them to Europe. Invoking a popular Ukrainian proverb, they stated that “even a mosquito can kill a horse with the help of a wolf.” In the estimation of the auuc, “the nationalists were the mosquito looking for a wolf [in the government], which would help them kill a communist.” While they maintained their intense animosity, the association’s executive decided to shift their focus to more productive matters like internal organizing and educational campaigns.51

What the auuc had not anticipated was that the threats posited in the Globe and Mail were not empty. According to the rcmp, dps had recently formed anti-communist blocs across the country that were dedicated to interrupting the activities of the auuc.52 As a result, members of the association were attacked throughout 1948. In November, a small bomb exploded inside the Labour Temple in Edmonton. Two days later, in Spedden, Alberta, dps entered an auuc meeting and struck a guest speaker. Later that month, in Saskatoon, an auuc gathering was interrupted by protestors who vandalized the Labour Temple. In Toronto, an auuc executive member was robbed at knifepoint after his house was broken into in what was described as a politically motivated crime.53

The worst attack of the year came on 11 December, when members of the Val-d’Or, Québec, branch gathered for a lecture by national executive member William Terecio. Terecio had recently returned from a lengthy trip to the Soviet Union and was now on a speaking tour of northern Ontario and Québec. A gifted orator, he usually had no trouble delivering rousing speeches that could inspire his audiences. Yet on this tour he was repeatedly confronted by angry mobs of dps who wanted to challenge his rosy narratives of the Soviet Union with their own first-hand accounts. The situation in Val-d’Or would be no different. As soon as Terecio began his talk, twenty angry dps armed with sticks, stones, and bottles stood up at the back of the hall and charged at him. Had it not been for a diligent group of supporters who jumped to his defence, the armed protestors would have reached him. As the two sides exchanged taunts and jabs, a major scuffle ensued. “Fascists!” auuc members yelled at the dps across the room. “We are not fascists,” they retorted, “but you are certainly communists!”

The mob was eventually removed, but they were not done for the night. After regrouping at their own hall just down the road, they decided to kidnap Terecio and drop him on the outskirts of town – a potential death sentence in the frigid December temperatures of northern Québec. But upon their return, the Labour Temple was dark. Terecio, who had fled town in the trunk of a car just minutes earlier, was nowhere to be found. Unsatisfied by the prospect of letting him off the hook, the group divided themselves into smaller teams to search and patrol the neighbourhood.54

The growing audaciousness of the dps was worrisome, and it prompted the auuc to write to Minister of Justice Stuart Garson. The association argued that the behaviour of the dps could no longer be attributed to a period of cultural adjustment but was rather an explicit expression of their fascist ideology. If the government did not intervene soon, the auuc warned, it would be sending a clear message of support that would lead to future incidents.55 Garson was concerned enough to forward the letter to Commissioner Wood. In response, Wood was dismissive, informing Garson that the dps had every right to confront the communists “for the purpose of hearing [them] praise this paradise on earth from which each of them recently managed to escape.” The commissioner reminded the minister of the critical utility of the dps in combatting the domestic left. They were the single greatest stumbling block that the auuc had ever encountered, he contended, and needed to be supported by all in the government. Wood also doubted the extent of the violence. While he conceded that a bomb had gone off in Edmonton, it was simply a stink bomb and had injured only a few. Plus, Wood would not rule out that the whole thing was a “false flag,” that is, that the auuc had set the bomb itself and placed the blame upon the dps. This, he claimed, was a common tactic of communists. Garson’s best bet, Wood advised him, was to reply to the auuc only to acknowledge that the content of its letter had been noted.56

The violence continued into 1949. On 16 October, 750 people poured into the Labour Temple in Winnipeg to hear Peter Krawchuk, a popular auuc leader, speak.57 Right before he took the stage, officials noticed that a large portion of the main floor and the entire east side of the balcony were filled with dps. Several hundred more were spotted milling about outside. The formal portion of the evening concluded without trouble, save for some minor heckling. The question-and-answer session got a bit more heated. The first trigger was a dp who asked Krawchuk a series of hostile questions about conditions in Soviet Ukraine. While Krawchuk stayed calm, the audience hissed at the man to sit down. From the balcony, a group of dps then began to shout at Krawchuk before pelting him with glass bottles. As he occupied low ground with missiles incoming, it was clear to Krawchuk that the event could not continue. A hasty motion to end the meeting was tabled and the audience was dismissed.

Fighting broke out in the rotunda and hallway as participants filed out of the Labour Temple. One police officer described an auuc member being stomped on. Another witness recalled seeing a group of dps smashing the front windows and turning the loose shards of glass into weapons. Robert Ciemny, a sixteen-year-old auuc member, was hospitalized after dps pulled him down the front steps and began kicking him in the head. Repeated efforts by the police to stop the fighting were futile. Every time they broke up one fight, a new one would start. To make matters worse, everyone was speaking Ukrainian and looked relatively similar, and the police struggled to differentiate them. All that could be done was to keep pushing people out on to the street to try to disperse them. By six o’clock in the evening all was finally quiet on Winnipeg’s northern front.58

In the aftermath of the conflict, the auuc issued a press release from provincial secretary Anthony Bileski demanding an inquiry into both the perpetrators and the police. Bileski declared that “the violence on October 16 was no accident. It was part of a whole plan of organized activity carried on against progressive Ukrainians with a view to repeating here the crimes they have committed in Europe.” This was no longer just an auuc or a communist issue, he reasoned, but rather an antifascist one. “It was from just such ‘small’ beginnings as this that the fascist terror swept Europe and set out to conquer the world. That fascism,” continued Bileski, “still has its international organizations [as seen] in the facts presented to Winnipeg citizens.” If nothing was done, “tomorrow it may well be a Jewish synagogue … a trade union hall, or a union worker.” It was imperative that both the public and the authorities clearly understood what had happened so that there would be “no repetition of storm trooper activities in Winnipeg.”59

The call for an inquiry into police methods was supported by several Labor-Progressive Party (lpp) aldermen, such as M. J. Forkin and Jacob Penner. In making their case, they charged that the police had intentionally delayed the arrival of reinforcements, made no serious attempt to protect auuc members, and avoided arresting the perpetrators despite the fighting lasting more than an hour. Their colleague, A. H. Fisher, was not as sympathetic, suggesting that “where there are communists there is likely to be agitation and strife.” While Penner made the case that being a communist did not disqualify one – or one’s property – from protection, Fisher was steadfast. He even went so far as to suggest that the auuc members involved in the fracas were “probably the same band of hooligans that broke plate glass windows here and smashed the plate windows of Forkin’s election headquarters.” This was a puzzling suggestion; Forkin was a member of the lpp and not exactly a target of fellow communists. Still, Fisher’s remarks were disconcertingly influential among other aldermen. When a motion for a public inquiry was tabled, it was defeated fourteen to three.60

The inquiry into who was responsible for the riot did move forward, but it was similarly tipped against the auuc. Early on, Winnipeg’s chief of police, Charles MacIver, publicly stated that the process would be fair and would hold those implicated in the riot responsible.61 But the investigation was left to Detective-Sergeant Robert Young, a member of the secretive “Subversive Squad.” This was a newly formed special division that worked with the rcmp to spy on and repress subversive activity in the city.62 In his report to MacIver, Young admitted that he did not believe the dps had done anything wrong and that they were being very forthcoming with information. As a result, he was inclined to believe them. This was enough to convince MacIver, whose final report concluded that the auuc was responsible for the trouble.63 He also announced that, after a discussion with Crown prosecutor Orville Kay, there was no evidence to prosecute anyone for the attack on Ciemny.64 When the news broke, it was celebrated by the Winnipeg Tribune, which berated the communists for “creating disturbances in various countries in accordance with their general policy of fostering strife and chaos.” The newspaper hoped that the report would have “a wholesome effect in preventing [the auuc] from ever again blaming what they call reactionary and fascist forces for trouble.”65

Disappointed, the auuc issued a statement warning that the inquiry’s lack of integrity and the absence of punishment would assuredly be “construed as a green light to hooliganism in this city, so long as it is committed in the name of anti-communism.”66 Still, Krawchuk’s tour carried on. He arrived in Timmins for his last stop on 11 December – a year to the day after Terecio’s attack in Val-d’Or. When the meeting started, a group of dps began banging on the door and yelling to be let in. auuc officials immediately called the police. When two officers eventually arrived on scene, they witnessed a crowd of about 200 trying to break down the front door. According to an auuc submission to the mayor, the officers claimed that the dps were not committing any crimes and, furthermore, that it was not the duty of police to intervene in disputes on private property. After politely asking the dps to disperse, they drove off in their cruiser, leaving members of the auuc trapped inside.67

Once the police left, the dps began throwing bricks and coal through the windows and eventually tore a railing from the front steps to use as a battering ram. When the door gave way, the dps began filing in. Terrified women and children rushed through the emergency exits into the darkened streets, not knowing if the mob awaited them. Those who stayed behind knew that they had no choice but to fight, and they readied themselves to defend their hall from the invasion.

Thomas Kremyr, who was unlucky enough to be standing in the foyer when the assault began, was dragged down the front stairs and beaten. His wife ran to his defence, but she was whipped with sticks and bottles. After several minutes the couple were pulled to safety, but Kremyr’s injuries were serious. Unconscious, he was taken to the hospital with internal bleeding and several broken bones. Local cio member Donald Mackenzie, who was only at the hall to help with lighting and sound for the event, was also taken to the hospital for a spinal injury. Steve Klapouschak, a sixteen-year-old, was treated for a deep cut to the back of his head.68 The hall was wrecked. The railings along the stairs were torn off, windows were broken, and the door was smashed in. There was glass, blood, and detritus everywhere.69

For the second time in one year, the auuc demanded an inquiry into the activities of the dps and the responses of a local police force. Kremyr’s brother, Stanley, himself a well-known local communist, spoke before city council.70 He was especially critical of the police, attesting that, in advance of the event, the local auuc had approached the police to provide a uniformed constable for the evening at the association’s expense. Its request was denied. He also submitted the sworn testimonies of several bystanders, none of whom had ties to the association and could be accused of bias. Witness A, a woman who lived across the street from the hall, stated that she had called the police after hearing the door being bashed in. When she told the responding officer that there were several injured people, she recalled him telling her that “those people have to look after themselves.” Witness B happened to be walking by as the fight occurred and ran to the aid of the injured. He identified the main aggressors to the officers, but they did not react to his prompts and told him to go home. Witness C likewise identified the instigators to the police and was told to mind their business.71

The evidence Stanley presented was overwhelming, and city council agreed to an inquiry. Shortly thereafter, however, it reneged on a technicality: the auuc’s resolution was deemed out of order. The auuc then sent its resolutions to Dana Porter, Attorney General of Ontario, asking for the province to step in. Porter did not reply.72

All the while, the newspapers in Timmins were flooded with articles that curiously mirrored the line propagated by the ucc, government officials, and the security service. “They have a story to tell too,” wrote the Daily Press alongside a photo of two dps holding a sharpened screwdriver and a wine bottle. Another article in the same newspaper claimed that the communists, armed with knives and chunks of coal, had attacked first. Any injuries they obtained were their own fault or were invented for sympathy. “Whom should we believe,” asked the Northern Daily News, “a Moscow sympathizer, Peter Krawchuk, or thousands of dps who fled from a ‘happy life’ in Russia in threadbare clothes? New Canadians came to hear Krawchuk’s speech, and he responded by creating trouble so that the communists did not learn of the true facts about life in Russia.”73

For the auuc, all hope was not yet lost. Several days after the attack, John Alexandrov, a 31-year-old dp who worked in the Hollinger Mines, was charged with assaulting Kremyr and fined ten dollars by the magistrate’s court for creating a disturbance.74 In preparation for Alexandrov’s trial, the Timmins branch of the auuc, alongside its allies, formed the Timmins Labor Defence Committee (tldc). The committee retained prominent lawyer (and Progressive-Conservative) Joseph Sedgwick to act as Kremyr’s counsel. All involved understood that the case would be tricky, but support for Kremyr was considerable. A petition calling for the prosecution and deportation of those responsible for the attack collected over 2,000 signatures, and a series of solidarity rallies were planned.75

Alexandrov’s trial was twice delayed because Kremyr’s injuries were so severe that he could not leave the hospital, but it finally began on 17 January 1950. The defence argued that Alexandrov had simply been at the wrong place at the wrong time. While he admitted to initially being at the Labour Temple, he said he had left as soon as his group was denied entry and only returned later to see what had unfolded. His lawyer further claimed that Alexandrov was only on the radar of the police because, after being questioned by an officer at the scene of the crime, he had lost his temper and was arrested for disorderly conduct. No matter what, though, Alexandrov was not responsible for the earlier violence. The blame, the defence maintained, lay squarely on the auuc.76

The prosecution hinged its case on several witnesses who each positively identified Alexandrov as one of the leaders of the attack and the one who had pulled Kremyr down the stairs. But according to Sedgwick, who was only observing the trial as Kremyr’s lawyer, the prosecution was making critical mistakes. For one, it did very little to challenge the defence’s claim that the auuc was responsible for the violence. It also did not call a single police officer to the stand. The defence called several, including an officer who seriously undermined the Crown’s star witness, Aileen Haillod. The officer recognized Haillod as having recently gone door to door in his neighbourhood collecting signatures for the tldc petition. He claimed that the petition demanded the deportation of all dps, which suggested a prejudice in Haillod. Yet the petition, which was in evidence and easily accessible to the prosecution, clearly only called for the deportation of those responsible for the attack. The prosecution similarly did not object to the inappropriate and easily objectionable statement by the same officer that, upon Alexandrov’s arrest for disorderly conduct, he did not look as though he had recently been in a fight. The prosecution did not call upon other witnesses either. Nick Hubaly, who could have testified to the auuc’s efforts to secure police protection for the event, and Roy Kuzenko, who recognized Alexandrov as the ringleader of an earlier attack on the hall, were both denied the opportunity to testify.77

Curious things were also happening behind the scenes. While Porter never responded to the auuc’s request for a provincial inquiry, he quietly pressured Sedgwick to step down as Kremyr’s lawyer. He further urged him to end his working relationship with the tldc. Sedgwick stayed on the case, but the veiled threat obviously got to him; his advocacy became tepid.78

In this context, the outcome of the trial is perhaps unsurprising. In his summation, Magistrate Atkinson acknowledged that a violent mob of dps had stormed the Labour Temple and caused bodily harm to several of its occupants, but he hesitated to convict, on the grounds that not all of the prosecution’s witnesses could identify Alexandrov by name at the time of the assault. Since a conviction might not stand up in a court of appeal, Atkinson felt it was best to simply dismiss the charges. In his closing remarks, the magistrate shared a homily that perhaps gave insight into where his own sympathies lay. “Live amicably,” he told the courtroom, “and remember we were all displaced persons at some time or another.” Not taking Atkinson’s advice to heart, and clearly unfazed by the proceedings of the trial, Alexandrov allegedly turned to Kremyr on his way out of the courtroom and whispered, “Now I’ll be able to get you, you dirty son of a whore.”79

Soon after the verdict was read, members of the auuc and tldc gathered to discuss their next steps.80 The possibility of appeal was rejected by Sedgwick on the grounds that doubts surrounding Alexandrov’s identification would remain.81 Talks of a civil lawsuit were also shelved due to the high cost and the fact that it felt “too removed from the scene of the struggle.”82 The only option left was a public inquiry, although Sedgwick cautioned that the odds here were also not good. Nevertheless, a delegation left for Queen’s Park to try to persuade Porter. The attorney general swiftly rejected the request, but he promised to have his department consult with city officials in Timmins to determine whether any further local action was appropriate. He never followed through.83

Perhaps tipped off by Porter, MacNamara, the deputy labour minister, issued an unprecedented statement on behalf of the federal government regarding the recent incidents in Winnipeg and Timmins. Repeating many of the same talking points that had long been circulating, he categorically denied that the dps were responsible for the brawls. Rather, he said, they had simply come to the halls to ask some questions and could not be held responsible for the fact that this provoked the communists to attack.84 For the auuc, MacNamara’s obfuscation of the facts made it clear that powerful forces were working against them. “[The dps] got off too lightly this time,” spokesperson Mike Korol protested, “and they know that the law will only smile and turn the other way.” In the past, the association had been “too soft, too easy, and too dependent on justice which just isn’t forthcoming.” The dps, Korol was sure, would continue to be legally absolved for their crimes so long as their victims were Reds. “In such a breeding ground,” he observed, “it is perhaps no surprise that fascism flourishes and grows like a weed in a neglected garden.”85

The Labour Temple in the aftermath of the bombing, n.d. © Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2022).

Royal Canadian Mounted Police fonds, vol. 2623, access request A-2015-00092, Library and Archives Canada.

A close-up of the damage, n.d. © Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2022).

Royal Canadian Mounted Police fonds, vol. 2623, access request A-2015-00092, Library and Archives Canada.

View from where investigators believe the bomb was placed, n.d. © Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2022).

Royal Canadian Mounted Police fonds, vol. 2623, access request A-2015-00092, Library and Archives Canada.

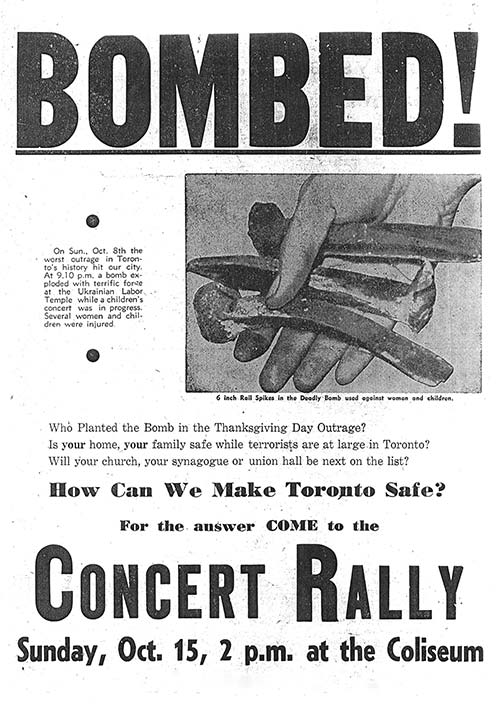

Poster advertising auuc concert rally, n.d. © Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada (2022).

Royal Canadian Mounted Police fonds, vol. 23, access request 93-A-00050, Library and Archives Canada.

On the evening of 8 October 1950, the Toronto branch of the auuc held a Thanksgiving concert in its Labour Temple, at 300 Bathurst Street. By eight o’clock in the evening, nearly 600 people had filed into the auditorium. In the basement, another 400 teenagers gathered for a fall dance. Just before nine o’clock, the master of ceremonies stepped onto the stage to introduce the concert’s next number. As they cued the music, a bomb exploded, shattering the large windows that flanked the hall and blanketing the audience with needle-like shards of glass. Railway spikes, which had been attached to the detonation device, blasted into the audience before lodging themselves into the walls and ceiling. The hall was darkened by dust and smoke, and all that could be heard were the loud screams of the injured and the frantic calls of parents searching for their children. As the cinders and shock settled, the audience surveyed the damage and began to evacuate. Most ran straight for the doors, but a few perceptive folks stayed behind. Rose Mickoluk, who was in the audience that night, later told a reporter that “if it was a dp attack, I’d be safer inside.”86

Others shared Mickoluk’s assessment that the bombing had been orchestrated by dps. Those who spoke to reporters tried to explain the attack by conveying the long and storied history of the Ukrainian Canadian community. Peter Prokop, national secretary of the auuc, was much more precise: he blamed the bombing on members of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician), otherwise known as the Galicia Division. Prokop claimed that over 1,000 members of the infamous unit were living in Canada.87 Given the nature of Prokop’s accusations, the rcmp was immediately informed of the incident. Detective-Sergeant Daniel Mann and Inspector K. Shakespeare, both of the anti-communist “Red Squad,” arrived on scene within the hour. Unlike in Edmonton, the officers could not dismiss this explosion as a stink bomb. They determined that it was either dynamite or nitroglycerine and had been ignited by a fuse and detonator cap. The investigators believed that the explosive had been placed outside, near a fire escape, which was easily accessible from a lane near the back of the building.

The next morning, rcmp officers and members of the Toronto police force returned to the Labour Temple to interview several witnesses. Distrustful of the police given their previous interactions, all were unwilling to talk except to provide the names of those they believed were responsible and point out that the bombing would not have happened had the government, police, and courts been willing to punish previous assailants. If officials were now serious about investigating the violence, they needed to stop protecting alleged “Nazi SS men trained in the criminal school of Hitler.” In a series of rallies held across the country in the weeks after the attack, the auuc reinforced its message to state officials. It was imperative that those responsible be imprisoned or deported this time, or else no Canadian would ever be safe from such mass acts of violence.88

The ucc did not take kindly to the comments of the auuc. The committee publicly accepted that a fair punishment needed to be doled out to whoever the bombers were but was adamant that the Galicia Division was not responsible. According to the ucc, members of the division were not even in Canada yet as they were under a wholesale ban by the government. This was not entirely true. Individual members had arrived in Canada as early as 1948, and Canada had reversed the embargo in May 1950. While additional screening measures undoubtedly precluded most division applicants from being in the country by October – making Prokop’s claims that over 1,000 members were already in the county highly unlikely – it was certainly possible that some had been let through.89 When this reality became impossible to deny, the ucc then avowed that participation in the division had been coerced in every instance and did not necessarily correlate with radical beliefs. The committee made clear that if the auuc did not immediately cease its slanderous statements, the executive would have no choice but to take the matter to the courts.90

Realizing that the scope of the case was becoming much larger than anticipated, the Toronto police requested that the rcmp stay on to assist them. In early November, the rcmp began its investigation into the presence of the Galicia Division in Canada and the whereabouts of specific individuals named by witnesses. This matter had already been investigated twice before. In April 1950, a report was produced by the Joint National Defence–External Affairs Intelligence Board. The rcmp conducted a second investigation a month later.91 This would be third investigation in under a year. It would be led by John Leopold, who famously spent the early years of his career spying on the cpc as a secret agent.92

Rather tellingly, correspondence between the Toronto police and the rcmp reveals that both groups had predetermined the innocence of the accused.93 All agreed that the bombing was yet another communist false flag and that the goal of their investigation was to clear those named as quickly as possible.94 In the following months, intelligence came pouring in about potential suspects. Most files were closed through alibi checks. Some were closed only after more thorough inspections. For example, the investigation into Petro Bihus unlocked serious questions after he admitted that he had, in fact, been a member of the Galicia Division. He insisted that he had not actually fought with the division; instead, he said, he had worked as a propagandist for the Ukrainian Central Welfare Committee (utsk), the Ukrainian representative body operative under the Nazi Generalgouvernement (General Government). Referring to Bihus as “the intellectual type,” the rcmp crossed him off their list.95

An identical defence was tabled by Andrij Palij, who told the interviewing officer that he had only been a member of the utsk. More specifically, he had been a member of the committee’s military board that, in consultation with local German police and administrative authorities, was responsible for all of the division’s recruitment activities. Palij, who had been tapped for the position because of his elite pedigree in western Ukraine, had not been conscripted.96 When questioned by a reporter as to whether he had ever fought with Hitler’s army, Palij responded that he had not – before flashing a wry smile.97

While claiming no personal knowledge of the bombing, Palij still insisted that it had been an inside job. This was a very common response by interviewees. Roman Rakhmanny (an alias for Roman Olynyk) admitted to fighting for the Germans between 1941 and 1944. This was ignored by the rcmp, however, who were much more interested in his claim that the bombing was a psychological campaign by the auuc to mislead the public. Similar to Palij, Rakhmanny denied any involvement but boasted that he “knew something about homemade bombs.” When he had made them back in Ukraine, though, “they didn’t just injure people – they killed.”98

Sometimes, suspects could not provide a credible alibi at all. This was the case with Dmytro Dontsov, a popular far-right theorist who had migrated first to the United States and then to Canada and was now employed by the Université de Montréal. While never a formal member of the oun, Dontsov helped the organization develop its ideology. In his writings, he advocated for a nationalism of the deed and the birth of a new man who was unafraid to mercilessly overthrow Ukraine’s enemies.99 As a professor, Dontsov would not have been teaching on the weekend. Direct inquiries with the local Ukrainian community also revealed that there were no functions that may have kept him in Montréal that weekend. Yet further efforts to interview Dontsov were shut down by the rcmp’s top brass.100 This was especially peculiar because Dontsov’s name had recently appeared on a list of Ukrainians accused of wartime collaboration. Most likely obtained from the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), the list had been included as an attachment in the previous two inquiries into the division.101

Walter Harris, the minister of citizenship and immigration, had seen the SIS list as part of the report by the Joint National Defence–External Affairs Intelligence Board. In the aftermath of the bombing, he reminded the rcmp of it and advised the officers involved to be on the lookout for any of the individuals named. The minister was undoubtedly concerned about the allegations against the Galicia Division, as he had been the one to personally lift the wholesale ban just a few months prior. Harris, however, would never know about Dontsov’s presence in Canada because it was never reported to him. Inspector A. W. Parsons dismissed the more serious charges against Dontsov as communist propaganda, and the file was swiftly closed.102

By December 1950, the rcmp was describing the case as dormant. According to the Toronto Board of Police Commissioners, which met in January 1951, the Toronto police still had officers assigned to the file who were trying to apprehend the suspects. But there were no new leads, and it was becoming increasingly doubtful that more could be done. In fact, the entire investigation was now reactive; both the rcmp and Toronto police did very little to pursue tips, update suspect lists, or analyze their intelligence work. rcmp records likewise reveal that most of their energies were seemingly spent spying on the auuc as the association demanded that the investigation continue. This surveillance included everything from watching organizers distribute informational pamphlets in McCreary, Alberta, to following the coverage of the case in the official Communist Party newspaper, Pravda. The force even spied on victims of the attack, including the aforementioned Nina Breshko; they worried that the fourteen-year-old might use the bombing as “a springboard for further attacks on the government.” Shortly after, the case was officially closed. No charges were ever laid, and the ongoing censorship of security files protects the identity of the rcmp’s main suspects more than 70 years later.103

The auuc was most likely incorrect in suggesting that the bombing was a coordinated attack by the Galicia Division. There is very little evidence to corroborate this, even with the understanding that state records come with their biases. The contention by the nationalists and state officials that it was an act perpetrated by the auuc on itself seems equally implausible given the documented history of prior attacks as well as the sheer ferocity of the bomb. The incident should be understood as the culmination of a low-level campaign of terror that dps unleashed against their political opponents in this era. The laxity with which the police, courts, security service, and government responded to these ongoing incidents demonstrates how, in the early years of the Cold War, law and justice were mutable and unevenly enforced depending on the political orientation of those involved. This history is instructive for understanding the irregular and discriminatory applications of legal regimes in Canada and the predictable capriciousness with which criminality is both articulated and enacted.

It is often believed that violence is a breakdown in communication. When two sides cannot agree and a middle ground seems impossible, violence erupts instead to subvert either further deliberation or the potential for resolution. In the case of the Ukrainian Canadian community, I suggest the contrary. Violence did not represent a failure to communicate. Nor was it the result of an inability to find a middle ground. Rather, violence was the continuation of political discourse by other means. The end of violence, then, was a reflection not of consensus but of a victory being reached in the contest for hegemony. Violence did not end because it ceased to be effective. It ended because the battle had been won.

Author’s Note

It is both legitimate and necessary for scholars to scrutinize the historical roots of Ukraine’s far right, its spread to Canada, and the subsequent impact on both domestic and foreign policy. However, attempts to utilize this research as an apologia for the imperialist ambitions of Vladimir Putin’s far-right, authoritarian regime are not supported by the author. Ukrainians, fighting against Russia’s unjustifiable invasion in February 2022, are worthy of solidarity and support. The actions of those who appear in this article must be independently adjudicated.

Thank you to Mikhail Bjorge, Ian Radforth, Franca Iacovetta, Rhonda Hinther, Julie Guard, Kirk Niergarth, Larissa Stavroff, and the anonymous reviewers for their support, advice, and helpful feedback.

1. The term “displaced person(s)” is a contentious one. There is evidence of it being used as a slur against migrants as they arrived in Canada after World War II. Later arguments have further problematized how “dp” reinforces notions of whiteness among a certain class of migrants, in contrast to racialized peoples, who are more commonly described as refugees. I am conscious of this context but have chosen to retain the term for several reasons. Most significantly, “dp” was a self-identifying marker for those whom this study is about. From a practical perspective, it is a clear way to distinguish between the established Ukrainian Canadian community and those who arrived after World War II, bringing with them their own distinctive social, cultural, and political outlooks. For a thorough overview of the dp experience, see Mark Wyman, DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945–51 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998). On Ukrainian dps, see Wsevolod Isajiw, Yury Boshyk & Roman Senkus, eds., The Refugee Experience: Ukrainian Displaced Persons after World War II (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1992).

2. H. L. Nieburg, Political Violence: The Behavioral Process (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1969); Kenneth McNaught, “Violence in Canadian History,” in J. S. Moir, ed., Character and Circumstance: Essays in Honour of Donald Creighton (Toronto: Macmillan Publishers, 1970), 66–84; Michael Kelly & Thomas Mitchell, “The Study of Internal Conflict in Canada: Problems and Prospects,” Conflict Quarterly 2, 1 (1981): 10–17; J. A. Frank, Michael J. Kelly & Thomas H. Mitchell, “The Myth of the ‘Peaceable Kingdom’: Interpretations of Violence in Canadian History,” Peace Research 15, 3 (1983): 52–60; Judy Torrance, Public Violence in Canada, 1867–1982 (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986); Scott See, “Nineteenth Century Collective Violence: Toward a North American Context,” Labour/Le Travail 39 (Spring 1997): 13–38; Elizabeth Mancke, Jerry Bannister, Denis McKim & Scott See, eds., Violence, Order, and Unrest: A History of British North America, 1794–1876 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019).

3. Of the capacious body of literature on Ukrainians in Canada, violence is addressed only in the following cases and always tangentially. See Michael Marunchak, The Ukrainian Canadians: A History (Winnipeg & Ottawa: Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences, 1970); Helen Potrobenko, No Streets of Gold: A Social History of Ukrainians in Alberta (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1977); John Kolasky, The Shattered Illusion: The History of Ukrainian Pro-Communist Organizations in Canada (Toronto: PMA Books, 1979); Lubomyr Luciuk, Ukrainians in the Making: Their Kingston Story (Kingston: Limestone, 1980); Jars Balan, Salt and Braided Bread: Ukrainian Life in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1984); Gregory Robinson, “Rougher Than Any Other Nationality? Ukrainian Canadians and Crime in Alberta, 1915–1929,” Journal of Ukrainian Studies 16, 1–2 (1991): 156–157; Peter Krawchuk, Our History: The Ukrainian Labour Farmer Movement in Canada, 1907–1991 (Toronto: Lugus, 1996); Bohdan Kordan, Canada and the Ukrainian Question, 1939–1945: A Study in Statecraft (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001); Vic Satzewich, The Ukrainian Diaspora (London: Routledge, 2002); Vadim Kukushkin, From Peasants to Labourers: Ukrainian and Belarusian Immigration from the Russian Empire to Canada (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007); Stacey Zembrzycki, According to Baba: A Collaborative Oral History of Sudbury’s Ukrainian Community (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2014); Myron Momryk, The Cold War in Val-d’Or: A History of the Ukrainian Community in Val-d’Or, Quebec (Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic, 2021).

4. Nieburg, Political Violence, 5.

5. A succinct critique of how hegemonic understandings of the Ukrainian Canadian community have shaped the historiography is offered in Rhonda Hinther, Perogies and Politics: Canada’s Ukrainian Left, 1891–1991 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 11–12. Hinther pushes back on the established narrative and begins to map how violence affected the auuc: violent incidents were more than petty intra-ethnic squabbles – they were critical moments through which organizations hardened their political outlooks (160).

6. See Marilyn Barber, “Nationalism, Nativism and the Social Gospel: The Protestant Church Response to Foreign Immigrants in Western Canada, 1891–1914,” in Richard Allen, ed., The Social Gospel in Canada: Papers of the Interdisciplinary Conference on the Social Gospel (Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1975), 186–226; David Rome, Clouds in the Thirties: On Antisemitism in Canada, 1929–1939 (Montréal: Canadian Jewish Congress, 1977); Peter Ward, White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy towards Orientals in British Columbia (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978); Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Japanese Canadians (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979); Donald Avery, Dangerous Foreigners: European Immigrant Workers and Labour Radicalism in Canada, 1896–1932 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979); Ann Sunahara, The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1981); Irving Abella & Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948 (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1982); Howard Palmer, Patterns of Prejudice: A History of Nativism in Alberta (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982); James W. St.G. Walker, Racial Discrimination in Canada: The Black Experience, Historical Booklet No. 41 (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1985); R. Bruce Shepard, “Plain Racism: The Reaction against Oklahoma Black Immigration to the Canadian Plains,” Prairie Forum 10 (1985): 365–382; Hugh Johnston, The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada’s Colour Bar (Vancouver: ubc Press, 1989); Patricia Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858–1914 (Vancouver: ubc Press, 1989); Martin Robin, Shades of Right: Nativist and Fascist Politics in Canada, 1920–1940 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991); Ruth Compton Brouwer, “A Disgrace to Christian Canada: Protestant Foreign Missionary Concerns about the Treatment of South Asians in Canada, 1907–1940,” in Franca Iacovetta, Paula Draper & Robert Ventresca, eds., A Nation of Immigrants: Women, Workers, and Communities in Canadian History, 1840s–1960s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 361–384; Alan Davies, ed., Antisemitism in Canada: History and Interpretation (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1999); Carmela Patrias, “Foreigners, Felonies, and Misdemeanours on Niagara’s Industrial Frontier, 1900–1930,” Canadian Historical Review 101, 3 (2020): 424–449.

7. J. K. Johnson, “Colonel James Fitzgibbon and the Suppression of Irish Riots in Upper Canada,” Ontario History 58 (1966): 139–155; H. Clare Pentland, Labour and Capital in Canada, 1650–1860 (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1981), 96–129; Michael Cross, “The Shiners’ War: Social Violence in the Ottawa Valley in the 1830s,” Canadian Historical Review 54, 1 (1973): 1–26; Robert F. Harney, “Men without Women: Italian Migrants in Canada, 1885–1930,” in Betty Caroli, Robert Harney & Lydio Tomasi, eds., The Italian Immigrant Woman in North America (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1978); Jean Morrison, “Ethnicity and Violence: The Lakehead Freight Handlers before World War I,” in Gregory Kealey & Peter Warrian, eds., Essays in Working Class History (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979), 143–160; Gregory Kealey, “The Orange Order in Toronto: Religious Riot and the Working Class,” in Kealey & Warrian, eds., Essays in Working Class History, 13–34; Ruth Bleasdale, “Class Conflict on the Canals of Upper Canada in the 1840s,” in Michael Cross & Gregory Kealey, eds., Pre-Industrial Canada, 1760–1849 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982); Ian Radforth, Bush Workers and Bosses: Logging in Northern Ontario, 1900–1980 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987); William Baker, “The Miners and the Mounties: The Royal North West Mounted Police and the 1906 Lethbridge Strike,” Labour/Le Travail 27 (Spring 1991): 55–96; Franca Iacovetta, “Manly Militants, Cohesive Communities, and Defiant Domestics: Writing about Immigrants in Canadian Historical Scholarship,” Labour/Le Travail 36 (Fall 1995): 217–252; Peter Way, Common Labour: Workers and the Digging of North American Canals, 1780–1860 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997); Angus McLaren, “Males, Migrants, and Murder in British Columbia, 1900–1923,” in Franca Iacovetta & Wendy Mitchinson, eds., On the Case: Explorations in Social History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 159–180; Nancy Forestell, “Bachelors, Boarding-Houses, and Blind Pigs: Gender Construction in a Multi-ethnic Mining Camp, 1909–1920,” in Iacovetta, Draper, and Ventresca, eds., Nation of Immigrants, 251–290; Thomas Dunk, It’s a Working Man’s Town: Male Working Class Culture in Northwestern Ontario (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003); Susan Brophy, “The Emancipatory Praxis of Ukrainian Canadians and the Necessity of a Situated Critique,” Labour/Le Travail 77 (Spring 2016): 151–179; Jeremy Milloy, Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Violence at Work in the North American Auto Industry, 1960–80 (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2017); Jeremy Milloy & Joan Sangster, eds., The Violence of Work: New Essays in Canadian and US Labour History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020).

8. Kathryn Harvey, “To Love, Honour, and Obey: Wife-Battering in Working-Class Montreal, 1869–79,” Urban History Review 19, no. 2 (1990): 128–141; Ellen Cole, Olivia Espin & Esther Rothblum, eds., Refugee Women and Their Mental Health: Shattered Societies, Shattered Lives (Binghamton: Haworth Press, 1992); Frances Swyripa, Wedded to the Cause: Ukrainian Canadian Women and Ethnic Identity, 1891–1991 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993); Swyripa, “Negotiating Sex and Gender in the Ukrainian Bloc Settlement: East Central Alberta between the Wars,” Prairie Forum 20, 2 (1995): 149–174; Marlene Epp, “The Memory of Violence: Society and East European Mennonite Refugees and Rape in the Second World War,” Journal of Women’s History 9, 1 (1997): 58–87; Epp, Women without Men: Mennonite Refugees of the Second World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000); Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006); Stacey Zembrzycki, “I’ll Fix You! Domestic Violence and Murder in a Ukrainian Working-Class Immigrant Community in Northern Ontario,” in Rhonda Hinther & Jim Mochoruk, eds., Re-Imagining Ukrainian-Canadians: History, Politics, and Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 436–464; Shahrzad Mojab, “The Politics of Culture, Racism, and Nationalism in Honour Killing,” Canadian Criminal Law Review 16, 2 (2012): 115–134; Franca Iacovetta, “Emotions, Marital Conflict, and Affect in the Multicultural Social Welfare Encounter,” Gender & History 31, 3 (2019): 605–623.

9. Johnson, “Colonel James Fitzgibbon”; E. C. Moulton, “Constitutional Crisis and Civil Strife in Newfoundland, February to November 1861,” Canadian Historical Review 48, 3 (1967): 251–272; James T. Watt, “Anti-Catholic Nativism in Canada: The Protestant Protective Association,” Canadian Historical Review 48, 1 (1967): 45–58; Michael Cross, “Stony Monday, 1849: The Rebellion Losses Riots in Bytown,” Ontario History 63 (1971): 177–190; George F. G. Stanley, “The Caraquet Riots of 1875,” Acadiensis 2 (1972): 21–38; A. Jeffrey Wright, “The Halifax Riot of April 1863,” Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly 4, 3 (1974): 299–310; A. J. B. Johnston, “Popery and Progress: Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Nova Scotia,” Dalhousie Review 64, 1 (1984): 146–163; J. R. Miller, “Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada,” Canadian Historical Review 66, 4 (1985): 474–494; Miller, “Bigotry in the North Atlantic Triangle: Irish, British and American Influences on Canadian Anti-Catholicism, 1850–1900,” Studies in Religion 16, 3 (1987): 289–301; Allan Greer, “From Folklore to Revolution: Charivaris and the Lower Canadian Rebellion of 1837,” Social History 15, 1 (1990): 25–43; Scott See, “Polling Crowds and Patronage: New Brunswick’s ‘Fighting Elections’ of 1842–3,” Canadian Historical Review 72, 2 (1991): 127–156; See, Riots in New Brunswick: Orange Nativism and Social Violence in the 1840s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993); John N. Grant, “The Canso Riots of 1833: ‘The Lawlessness of These People Is Truly Beyond … Comprehension,’” Nova Scotia Historical Review 14 (1994): 1–19; Ian Radforth, “Playful Crowds and the 1886 Toronto Street Railway Strikes,” Labour/Le Travail 76 (Fall 2015): 133–164; Mancke et al., Violence, Order, and Unrest.

10. Reginald Whitaker, Double Standard: The Secret History of Canadian Immigration (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987); Mark Kristmanson, Plateaus of Freedom: Nationality, Culture, and State Security in Canada, 1940–1960 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002); Iacovetta, Gatekeepers; Ivana Caccia, Managing the Canadian Mosaic in Wartime: Shaping Citizenship Policy, 1939–1945 (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010); Ninette Kelley & Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010); Julie Gilmour, “The Kind of People Canada Wants: Canada and the Displaced Persons, 1943–1953,” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2011.

11. It is reasonable to believe that low-level state officials (local police and courts) did not understand the political sophistication of the dps and assumed that their aggressive outbursts were individualized retributions for Old World grievances. When confronted with their support for the dps, the upper echelons of the state gave further credence to the notion that differences of opinion on Soviet Ukraine simply bred hostility. When it came to violence that aligned with the state’s ideological proclivities, such plausible deniability was extremely beneficial. For the dps and their allies, this cover gave them the necessary room to proliferate their anti-communism to an even larger audience and, in turn, to help define the acceptable parameters of political belief in Cold War Canada.

12. Peter Krawchuk, The Ukrainian Socialist Movement in Canada, 1907–1918 (Toronto: Progress Books, 1979), 3–5; Orest Martynowych, Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Years, 1891–1924 (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1991), 24.

13. Kassandra Luciuk, “Reinserting Radicalism: Canada’s First National Internment Operations, the Ukrainian Left, and the Politics of Redress,” in Rhonda Hinther & Jim Mochoruk, eds., Civilian Internment in Canada: Histories and Legacies (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2020), 49–69.

14. On the Ukrainian left as it became explicitly pro-communist, see Kolasky, Shattered Illusion; John Kolasky, Prophets and Proletarians: Documents on the History of the Rise and Decline of Ukrainian Communism in Canada (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1990); Krawchuk, Our History.

15. Krawchuk, Our History, 42–45.

16. Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 13.

17. Martynowych, Ukrainians in Canada, 265.

18. Orest Martynowych, “Sympathy for the Devil: The Attitude of Ukrainian War Veterans in Canada to Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933–1939,” in Hinther & Mochoruk, eds., Re-imagining Ukrainian-Canadians, 198.

19. Martynowych, Ukrainians in Canada, xxix.

20. Olha Woycenko, The Ukrainians in Canada (Winnipeg: Trident Press, 1967), 200; Satzewich, Ukrainian Diaspora, 69.

21. The guiding ideology of the oun is unpacked in Karel Berkhoff & Marco Carynnyk, “The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Its Attitude toward Germans and Jews: Iaroslav Stetsko’s 1941 Zhyttiepys,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 23, 3–4 (1999): 149–184; John Paul Himka, “The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army: Unwelcome Elements of an Identity Project,” Ab Imperio 4 (2010): 83–101; Myroslav Shkandrij, “National Democracy, the oun, and Dontsovism: Three Ideological Currents in Ukrainian Nationalism of the 1930s–40s and Their Shared Myth-System,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48, 2–3 (2015): 209–216.

22. “Ukrainian National Organization,” 13 October 1933, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (rcmp), rg146, vol. 38, access request 94-A-00180, Library and Archives Canada (lac); “Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (uno) or Ukrainian Military Organization,” 13 October 1933, rcmp, rg146, vol. 38, access request 94-A-00180, lac; “Re: Ukrainian Nationalists, Canada – Generally,” 25 January 1939, rcmp, rg146, vol. 38, access request 94-A-00180, lac; “Ukrainians in Canada: Connection between the uno, the Hetman Seetch, and the Canadian Fascist Groups,” n.d., rcmp, rg146, vol 38, access request 94-A-00180, lac.

23. Martynowych, “Sympathy for the Devil,” 198.

24. It is difficult to ascertain accurate membership numbers for the committee, owing to its status as an umbrella outfit. Based on figures provided by Martynowych for just three of its major five organizations, the ucc had at least 10,000 constituents in its formative years. Martynowych, “Sympathy for the Devil,” 198. See also “Ukrainian National Organization,” 13 October 1933, lac; “Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (uno) or Ukrainian Military Organization,” 13 October 1933, lac; “Re: Ukrainian Nationalists, Canada – Generally,” 25 January 1939, lac; “Ukrainians in Canada: Connection between the uno, the Hetman Seetch, and the Canadian Fascist Groups,” lac.

25. The Ukrainian Canadian Committee has since changed its name to the Ukrainian Canadian Congress. For a broad overview of the Canadian government’s management of Ukrainian nationalists in this period, see Kordan, Canada and the Ukrainian Question, 137–176.

26. “Report on the Ukrainian Canadian Committee,” 18 September 1941, TP, MG30 E350, vol. 1, file 15, lac; “Committee Is Political Watchdog,” Winnipeg Tribune, 6 April 1957.

27. Luciuk, Searching for Place, 213.

28. Lubomyr Luciuk, “‘This Should Never Be Spoken or Quoted Publicly’: Canada’s Ukrainians and Their Encounter with the dps,” in Lubomyr Luciuk & Stella Hryniuk, eds., Canada’s Ukrainians: Negotiating an Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 103–122; Howard Margolian, Unauthorized Entry: The Truth about Nazi War Criminals in Canada, 1946–1956 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000), 116–147.

29. Julia Lalande, “‘Building a Home Abroad’: A Comparative Study of Ukrainian Migration, Immigration Policy and Diaspora Formation in Canada and Germany after the Second World War,” PhD diss., University of Hamburg, 2006, 148.

30. “Ukrainian Collaborationists Entry Opposed,” Winnipeg Free Press, 11 December 1943; “Ukrainske Slovo,” 17 October 1945, rcmp, rg146, vol. 95, access request ah-1999/00134 pt. 3, lac; “Ukrainian Canadian Association,” 15 December 1945, rcmp, rg146, vol. 95, access request ah-1999/00134 pt. 3, lac; “Re: Ukrainian Canadian Association, Winnipeg,” 21 December 1945, rcmp, rg146, vol. 95, access request ah-1999/00134 pt. 3, lac.

31. The auuc’s position on the dps is outlined in detail in Kolasky, Prophets and Proletarians, 341– 358; Krawchuk, Our History, 284–287.

32. “Re: Subversive Activities among dps – General,” 9 December 1947, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac; “Re: Communist Activities amongst Immigrants from dp Camps – Rouyn-Noranda, P.Q.,” 24 December 1947, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac; “Association of United Ukrainian Canadians, Winnipeg, Manitoba,” 16 April 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 95, access request ah-1999/00134 pt. 3, lac; “Subversive Activities, Raynor Construction Co., Thessalon, Ont.,” 1 April 1949, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac; “Re: Association of United Ukrainian Canadians – Val d’Or, P.Q.,” 17 November 1949, rcmp, rg146, vol. 33, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

33. “We Didn’t Like: 59 dp Miners Toss 2 Off Train,” Toronto Daily Star, 16 December 1947; “Welcome the Freedom Loving,” Montreal Gazette, 24 December 1947; “Met at the Train,” Time, 5 January 1948.

34. “Re: Association of United Ukrainian Canadians – Grimsby, Ontario,” 22 November 1947; “Re: Ukrainian Life,” 25 December 1947, both in rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

35. “Re: Association of United Ukrainian Canadians – Wakaw, Sask.,” 10 March 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

36. “Re: An Incident in a Camp,” 14 October 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

37. “14 Arrested after Bitter Fight in Bush,” Ottawa Citizen, 18 June 1948; “Lumberjacks in Bitter Camp Fight,” Ottawa Journal, 18 June 1948.

38. Panchuk to King, 2 March 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00198, lac.

39. “Criticism of Immigrants Work of Reds – Robertson,” The Star, 11 March 1949; “The Anti-Immigrant Campaign,” The Star, 18 March 1949.

40. Sharrer to MacNamara, 22 March 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

41. Gilmour, “Kind of People,” 206–213; “dps in Mines Learning Customs of Canadians,” Globe and Mail, 20 February 1948.

42. “dps Almost Man to Man against Communism,” Globe and Mail, 23 February 1948; “Re: Communist Activities amongst Immigrants from dp Camps – Rouyn-Noranda, P.Q.,” 15 April 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00198, lac. On the efforts to purge communist influence from the labour movement, see Reg Whitaker & Gary Marcuse, Cold War Canada: The Making of a National Insecurity State, 1945–1957 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 310–341; Gary Marcuse, “Labour’s Cold War: The Story of a Union That Was Not Purged,” Labour/Le Travail 22 (Fall 1988): 199–210; Ron Verzuh, “The Raiding of Local 480: A Historic Cold War Struggle for Union Supremacy in a Small Canadian City,” Labour/Le Travail 82 (Fall 2018): 81–117.

43. “Need of Wider Contacts in Order to Study the Situation,” February 1941, Tracy Philipps fonds, MG30 E350, vol. 1, lac; “Ukrainian Canadians Condemn Communism,” Winnipeg Free Press, 21 April 1948; “Back Unions, Beat Reds, Ukrainian Workers Told,” Winnipeg Free Press, 10 July 1953.

44. “Re: Alleged Subversive Activity amongst Displaced Persons, Regan, Ontario,” 10 February 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00198, lac.

45. For more on Lobay, see Andrij Makuch, “Fighting for the Soul of the Ukrainian Progressive Movement in Canada: The Lobayites and the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association,” in Hinther & Mochoruk, eds., Re-imagining Ukrainian-Canadians, 376–400.

46. “Need of Wider Contacts,” lac; “Ukrainian Canadians Condemn Communism”; “Back Unions, Beat Reds.”

47. On the oun in Canada, see Lubomyr Luciuk & Marco Carynnyk, eds., Between Two Worlds: The Memoirs of Stanley Frolick (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1990); Luciuk, Searching for Place, 198–244; Orest Martynowych, “A Ukrainian Canadian in London: Vladimir J. (Kaye) Kysilewsky and the Ukrainian Bureau, 1931–1940” Canadian Ethnic Studies 47, 4–5 (2015): 263–288.

48. “Re: Novy Shlyakh (The New Pathway),” 20 September 1947, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00198, lac; “Re: Alleged Subversive Activity amongst Displaced Persons, Regan, Ontario,” 10 February 1948, lac; “Re: Alleged Communist Activities among Displaced Persons – Thessalon, Ontario,” 14 January 1949, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac; Kulyk to Frolick, 3 August 1947, Stanley Frolick papers, MG31 H32, vol. 3, lac.

49. Kassandra Luciuk, “Making Ukrainian Canadians: Identity, Politics, and Power in Cold War Canada,” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2021, 30–77.

50. “dps Almost Man to Man.”

51. “Association of United Ukrainian Canadians, Winnipeg, Manitoba,” 9 January 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 95, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

52. “Re: Vasil M. Terecio – Toronto, Ont.,” 12 April 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 33, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

53. “dps Almost Man to Man”; “Re: Communist Activities amongst Immigrants from dp Camps – Rouyn-Noranda, P.Q.,” 15 April 1948, lac; “Ukrainian Urges Action in Riot,” Winnipeg Free Press, 9 November 1948; auuc to Garson, 24 November 1948, Stavroff Private Collection.

54. “Re: Association of United Ukrainian Canadians, Val D’Or, Que.,” 11 December 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 33, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

55. auuc to Garson; “Bombing – 300 Bathurst Street,” Stavroff Private Collection.

56. Wood to Garson, 27 December 1948, rcmp, rg146, vol. 39, access request 94-A-00182, lac.

57. Krawchuk, Our History, 285; Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 160.

58. “Re: Disturbance at the Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 18 October 1949, Stavroff Private Collection; “Re: Fracas at Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 18 October 1949, Stavroff Private Collection; Elliott to MacIver, 18 October 1949, Stavroff Private Collection; Talbot to MacIver, 18 October 1949, Stavroff Private Collection; “Re: Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 22 October 1949, Stavroff Private Collection.

59. “dp’s Battle Leftist Crowd at City Meet,” Winnipeg Tribune, 17 October 1949; “Forkin Urges Mayor Probe Charge Police Lax at Fracas,” Winnipeg Free Press, 18 October 1949; “Ukrainian Association Demands Probe of Riot,” Winnipeg Free Press, 24 October 1949; “Yes, Who Are the Fascists, Rev. Izyk!,” n.d., Stavroff Private Collection; “Not an Accident,” n.d., Stavroff Private Collection; “Operation Canada,” n.d., Starvroff Private Collection.

60. “Aldermen Ask Probe of Riot,” Winnipeg Tribune, 18 October 1949.

61. “Police Study Riot Action,” Winnipeg Tribune, 19 October 1949; “MacIver’s Report on Fracas Going to Commission,” Winnipeg Tribune, 15 November 1949.

62. “New Subversive Squad Revealed,” Winnipeg Tribune, 22 November 1949. The activities of the Subversive Squad are briefly discussed in Doug Smith, Joe Zuken: Citizen and Socialist (Toronto: James Lorimer, 1990), 137.

63. “Re: Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 22 October 1949; “Re: Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 1 November 1949; MacIver to Board of Police Commissioner, 14 November 1949, all in Stavroff Private Collection.

64. MacIver to Board of Police Commissioners.

65. “Police Commission Report,” Winnipeg Tribune, 28 November 1949.

66. Bilecki to Coulter, 23 November 1949, Stavroff Private Collection.

67. “auuc Submission to Mayor and Council,” 15 November 1949, Stavroff Private Collection.