Labour / Le Travail

Issue 90 (2022)

Archives Report / Chroniques d’archives

Working People Built This Archive: The IWA Archive and Woodworker History

In 2021 an archive dedicated to the history of the International Woodworkers of America (iwa) opened in Kaatza Station Museum in Lake Cowichan, on unceded Ts’uubaa-asatx territory, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia. The International Woodworkers of America originally operated in British Columbia as iwa District Council #1. During the 1950s the district office assumed responsibility for operations in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, becoming iwa Western Canada Regional Council #1. In 1987 the decision was made to separate from the Portland-based International union. The subsequent merging of Western Canada Regional Council #1 and Eastern Canada Regional Council #2 created a nationwide leadership structure, with its head office in Vancouver, BC, under the name iwa Canada.1 The iwa Archive is the product of decades of labour, a product of working people – until recently, independent from the support of academic institutions – taking the production of their history into their own hands. The archive’s arrival in Lake Cowichan and its organization (and administration) are the result of years of dedicated working-class do-it-yourself archiving as well as a commitment to historical conservation that extends back to the 1970s.

In 1977 the acclaimed populist American historian Howard Zinn wrote that the availability of historical records and archives is “very much determined by the distribution of wealth and power” and that the capacity for maintaining and controlling documentary records is dominated by “government, business, and the military.” Zinn concluded by calling on archivists to “play some small part in the creation of a real democracy” by taking “the trouble to compile a whole new world of documentary material, about the lives, desires, needs, of ordinary people.”2 Since then, many historians and archivists have considered how archives dedicated to displaced peoples and organizations – including social movements, queer communities, racialized people, Indigenous communities, working-class people, and the labour movement – are themselves a constituent element in resisting the triumphalist homogenizing narratives of nationalism and capitalist supremacy.

As Jessica Pauszek argues, the solution to problems related to the precarious nature of working-class historical documentation – “precarity” referring to the lack of financing, technical expertise, institutional support, or basic storage space – is to “create archives with community members based on their expertise and embodied experiences.”3 Several scholars have foregrounded the need for a mode of historical production that emphasizes “co-creation,” “democratization,” and “participatory scholarship.”4 Indeed, the very process of historical production, and the participation and leadership of community members in that process, can be a crucial underpinning in the creation of identity and the reaffirmation of class consciousness.5

The histories being told in the iwa Archive emphasize the diversity of labour organizing efforts in western Canada, which includes commitment to class, racial, and gender justice. But the history of the iwa is also a reminder of the painful challenges inflicted on workers by neoliberal economic and political shifts and the often underrecognized commitment that workers and unionists have held to various political and social causes. In British Columbia, that includes a less well known commitment by the iwa to environmental protection. These are stories that would not be openly available without the self-motivated commitment to labour heritage possessed by union members dedicated to the preservation of their union’s heritage and of their historical identity as woodworkers.

The Woodworkers’ Archive: Working People Create the Archive

The records in the archive were initially produced by several offices of the iwa, which was the largest industrial union in western Canada for much of the region’s history. The iwa represented workers in falling camps, lumber and pulp mills, and beyond. Collections currently include records produced by the district/regional/national headquarters of the union, which was in Vancouver, as well as local union offices in Vancouver (Local 1-217), Duncan (1-80), New Westminster (1-357), Courtenay (1-363), and the large local union that covered fallers in locations ranging from the Sunshine Coast to Haida Gwaii (1-71). Future acquisitions will follow, with the Port Alberni (1-85) local union records on order and a long-term plan in place to acquire records from local union offices across British Columbia and throughout Canada.

The two largest collections of records that now sit in the archive are those belonging to the Vancouver-based national office and those produced by the Duncan local union office. Both collections were created and managed over the years by local union members and officers. The enormous collection of photographs, files, convention proceedings, and minutes that originated with the iwa Canada head office was managed in-house by legislative director Clay Perry for 30 years. Norm Garcia, editor of the union’s publication the BC Lumber Worker, took over responsibility for the archives following Perry’s retirement.6 The Duncan local union’s historical archive was originally started by local president Roger Stanyer but was taken over by Ken McEwan, editor of the local’s newspaper, the 1-80 Bulletin, until his employment with the iwa ended in 1989. The archive primarily consisted of photo collections, including the famed Wilmer Gold Photo Collection, but McEwan also conducted interviews and collected written records. Following this, Allan Lundgren – a veteran faller, local historian, and the son of a founding member of the iwa – took over management of the 1-80 archive.

How this enormous and nationally significant archival collection ended up at a small rural museum with only one full-time staff member is testimony once more to the immense determination of the working-class volunteers who took on responsibility for ensuring the survival of their union’s documentary history. It also reveals the fundamental flaws and limitations addling institutional archives and educational structures more broadly in the neoliberal era.7 Because of limitations on funding, staffing, and space, not the University of British Columbia (ubc) Rare Books and Special Collections, nor the Simon Fraser University Archives, nor the City of Vancouver archives was able to undertake the enormous task of housing the 300-box collection of documents and photographs.

In 2014 Lundgren and Garcia partnered with former iwa Canada and United Steelworkers staffer John Mountain to locate a suitable venue for the collection. After several setbacks, Lundgren suggested the Kaatza Station Museum in Lake Cowichan, a largely volunteer-powered organization that he had volunteered with in the past and that had previously taken responsibility for Local 1-80’s collection of historical photographs and records. According to Mountain, it was the “grass-roots can-do attitude of the Kaatza Historical Society” that made it a favourable venue for the records.8 When the trio of working-class archivists approached the board of the Kaatza Historical Society, which oversees the museum, board members were, according to society president Pat Foster, “absolutely delighted to take on this important responsibility.”9

However, the small museum was limited in both space and finances, and, in order to house the collection, the historical society developed a plan to extend the museum’s archival space by constructing an annex. Once more, large institutional structures appeared indifferent to the project. For instance, the museum applied for funding to Library and Archives Canada and to Heritage Canada; both applications were rejected due to the perceived inability of the museum to take on such an ambitious archival project. Once more, then, it fell to the local community of woodworkers – exhibiting union solidarity that extends beyond retirement – to build a home for these historical materials without the financial or technical support of government or educational institutions.

It was their commitment to preserving the working-class history of woodworkers in Canada that led to the Kaatza Station Museum achieving what larger institutions declared would be impossible. Local fundraising, boosted by a generous donation of $15,000 from the United Steelworkers District 3, raised $60,000 in donations and in-kind services. Former iwa members and officers donated money, materials, and services such as planning, electrical engineering, roofing, construction, and carpentry. The resulting iwa Annex is externally layered with cedar shake; inside, the walls surrounding the collection are adorned with banners, union constitutions, and photographs of forestry operations, labour leaders, and conventions. The wealth of material in the archive is a proud testament to local people’s steadfast loyalty to the labour union that walked hand-in-hand with Cowichan’s woodworking community through the boom years and the years of decline.10

Part of the iwa Collection arrives at Kaatza, 2016.

Kaatza Station Museum and Archives Photograph Collections.

To be sure, larger educational institutions have played some role in creating the archive, especially more recently. My own involvement as project archivist, beginning in 2020, came about through my enrolment in ubc’s Arts PhD Co-op Program, and successful recent fundraising for wages and supplies has come about thanks to advising from ubc’s Arts Amplifier unit.11 This has led to several government grants to support the archiving of the collection, as well as contributions from the United Steelworkers, the Community Savings Credit Union, and an anonymous philanthropic foundation. Equally, archival arrangement and description has been possible through the mentoring and support of Claire Williams, forestry archivist at ubc Rare Books and Special Collections. Nevertheless, relative frivolities such as correct archival arrangement and finding aids that adhere to the Rules for Archival Description are in many ways the veneer applied to lumber that has been grown, felled, transported, and milled by the calloused hands of former woodworkers and working-class community members.

The iwa Annex almost completed, 2019.

Kaatza Station Museum and Archives Photograph Collections.

As well as being the product of decades of collecting, conserving, and managing by members of the labour movement, the contents of this archive contain insights into aspects of the labour movement and of the forest industry that are so far relatively unexplored by historians.12 In particular, these relate to the role played by racialized people and women in the union’s early organizing, as well as the “green” side of the iwa, as the union battled for more sustainable and less environmentally damaging forestry practices throughout its history.

Arranging the iwa Archive, 2021.

Photo courtesy of Kaden Walters.

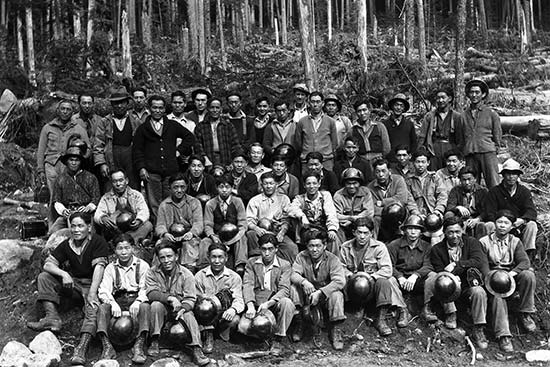

Hillcrest Lumber, Sahtlam Logging Division, 1940.

Wilmer Gold Collection, N01673, iwa Local 1-80 fonds, Kaatza Station Museum and Archives. © United Steelworkers of America 1-1937.

The Role of Racialized People and Women in the Early Success

of the Union

In June 2021, Kaatza Station Museum’s iwa Archive hosted its first major research project and was visited by researchers working on the BC Labour Heritage Centre’s South Asian Labour History Project. Publications that have emerged from this research detail the active role that the union’s leadership played in campaigning for equal rights for South Asian workers and demonstrate in turn the key role South Asian organizers played in exponentially expanding the union.13 In its second decade of organizing in British Columbia, the iwa expanded from 1,151 members in 1941 to 24,453 in 1948.14 Although there is currently a lack of data regarding the racial breakdown of new members during this period, it seems that one of the key factors underpinning this membership explosion was the iwa’s strategy of hiring racialized people as organizers in order to unionize non-white workers.

As Anushay Malik has outlined, building on research conducted at the iwa Archive and elsewhere, it was only through the actions of organizers such as Darshan Singh Sangha that the iwa was able to unionize several mills that employed predominantly South Asian labour. Furthermore, such organizers also articulated “anti-colonial, pro-working class and pro-union ideals” that connected the union to broader progressive anti-racist struggles over the franchise and equal pay.15 So far, records created directly by Sangha – through his work with Victoria’s Local Union 1-118 and the BC District Council #1 – have proven to be elusive, although the archive does hold documentary evidence of his participation in meetings and conventions, his speeches, and his literary contributions to the BC Lumber Worker newspaper.

The organically expansive nature of the iwa Archive means that since the archive hosted the South Asian Labour History Project, fresh acquisitions have shone new light on the topic. Correspondence files from the 1940s – recently discovered by John Mountain in the basement of the United Steelworkers Local 1937 office in Duncan, BC – have revealed a previously unknown South Asian organizer operating in Port Alberni, who even published his own union newsletter in Punjabi.16 The archive is hoping that upcoming acquisitions from the former office of iwa Local 1-85 (Port Alberni), along with further community outreach, will provide additional insights into the organizing of South Asian workers in both the Alberni region and British Columbia more broadly.

To these historical records should be added the newspaper stories, letters, interviews, and meeting minutes detailing the activism of Chinese and Japanese Canadian organizers such as Roy Mah and Joe Miyazawa, as well as the records of iwa Women’s Auxiliary activists Edna Brown and Olive Leaf. In consulting this diversity of documentary material held in the iwa Archive, it is clear that racialized peoples and women played essential roles in the history of the union, especially during its moments of greatest success and expansion. Considering that a great deal of scholarship has focused on the dominance of white men in industrial unions, this new archival material undoubtedly demonstrates a pressing need for future research in this area.

The IWA and Neoliberalism in the 1980s

Because of the size of the organization, the number of people involved, and the fact that the archiving of the union’s records has taken place in several waves, several repositories in British Columbia hold records produced by the iwa. ubc Rare Books and Special Collections holds records donated by the charismatic first president of the union, Harold Pritchett, as well as records donated by the iwa District/Regional Council #1 that mainly cover the union’s history up until the end of the 1970s.17 In addition to these records, ubc Rare Books and Special Collections holds a relatively small collection donated by Clay Perry, research director and then legislative director for iwa Canada.18 However, compared with these collections, the iwa Archive at Kaatza contains a far fuller record of historical and administrative documentation of the union’s early and middle years in British Columbia, particularly as it holds the records of local union offices documenting the grassroots activities of the union.

Moreover, the archive holds the only complete collection of records produced by iwa Canada during its later years, between 1980 and 2000 – years that were crucially important in the history of forestry and the labour movement in western Canada. These records provide both a documentary record and personal insight into the challenges faced by union officers and staff during the onset of neoliberalism in the 1970s and 1980s. The union dedicated vast resources at both the national and regional levels to tracking and mitigating the disastrous job losses in that era.19 This work left an exhaustive trove of studies, technology reviews, meeting minutes, and industrial negotiations documenting the union’s responses to the calamitous decline in the power of the forestry workforce.

Of note here are the records of Jack Munro, perhaps the best-known face of the iwa during the 1980s, which contain the president’s administrative, research, and personal records from this period. For instance, one folder of these records contains Munro’s correspondence related to the infamous 1986 industry-wide provincial strike. Labelled the “$2 billion strike” by the Vancouver Sun, the 1986 strike saw nearly 20,000 workers off work for four and a half months and reduced the Western Canada Regional Strike Fund to a single $20 note.20 Unsurprisingly, the letters written to Munro during the strike are a motley collection of emotional responses, some praising the union leader for his strong stance during the strike but many bemoaning the lengthy time off work and workers’ inability to support their families. Having only read media accounts of Munro being a larger-than-life, bellicose, and belligerent leader, I was surprised and touched by the sensitivity in many of his responses, especially in his replies to children’s letters.21

The IWA and Environmentalism

There is an increasing trend in both histories of environmental organizations and histories of labour unions to consider the historical relationship between the two movements.22 However, for an analytic approach with such clear significance for contemporary struggles, this is still an area that requires further research. Indeed, continuing scholarly challenge is required to combat the basic assumption that environmentalists and working-class resource extraction communities have been and remain diametrically opposed and mutually exclusive.23 While media outlets in the 1980s and 1990s were keen to feature leaders of iwa Canada slinging insults at old-growth preservation campaigns, the records contained in the iwa Archive shed light on a more complex relationship – one in which union officers, staff, and members took seriously the responsibility of tending to the forest while holding company bosses accountable for environmental damage.24

What records from both iwa Western Canada Regional Council #1 and the local union offices demonstrate is that woodworker unionists, along with the broader labour movement, were strong supporters of the environmental movement in British Columbia during the “green wave” of the early 1970s.25 For instance, Regional Council #1 made an annual membership donation of $50 to the Society for Pollution and Environmental Control (spec) and distributed spec petitions regarding industry pollution for local union officers to pass on to plant chairpersons.26 Perhaps surprisingly to those familiar with the mid-1990s spat between iwa Canada and Greenpeace, records and union newspapers show that in 1971 iwa officers in British Columbia were fully supportive of the Greenpeace Expedition that protested nuclear testing in Amchitka.27 For instance, as reported in the 1-80 Bulletin, officers of Cowichan’s Local 1-80 donated an hour’s wages to the expedition and encouraged members to take part in an hour-long work stoppage to oppose the test.28

Even with the outbreak of the so-called War in the Woods in the 1980s and 1990s – a struggle over old-growth forest preservation that continues to this day – the officers of iwa Canada maintained a far greater emphasis on environmental principles than has previously been acknowledged. Certainly, the iwa Archive contains much documentary evidence of their hostility toward preservationists during those decades. For instance, records of the union’s research department contain notes and drafts generated by staff in co-writing president Gerry Stoney’s famous anti-environmentalist address at the 1993 “Share BC” yellow-ribbon event in Ucluelet, a counter-protest to the Clayoquot Sound blockades.29 Equally, the archive contains a fascinating handheld-camera recording on vhs of iwa Canada’s blockade of two Greenpeace vessels docking in Vancouver in 1997.30

However, sources documenting such moments of confrontation are fairly evenly balanced in the iwa Archive by sources that shed a light on the woodworking environmentalism that union leaders pursued in the same period. For instance, the Bill Routley Papers contain documentary evidence of environmental projects taken up by the Local 1-80 president during his tenure. These include the Woodworkers Survival Task Force, a special committee formed with environmentally conscious faller Joe Saysell to investigate the multinational Fletcher Challenge’s poor environmental standards and raw log exports in the Cowichan, Renfrew, and Nitinat regions.31 Furthermore, an oral history archive – currently in progress but intended to house interviews with Routley as well as iwa Canada’s research director Phillip Legg and environment/land use planner Claire Dansereau – provides background on moves made by union leadership to build links with the environmental movement, such as their Forest Policy 1989 and the 1991 South Island Forest Accord.32

Conclusion: Continuing to Build the Archive

The records of the iwa Archive provide insights into critical historical questions regarding the sociocultural trajectories of the labour movement, of the anti-racist struggle, and of the nature of the environmental movement. These questions continue to hold resounding salience in our present moment. To be sure, the records of the archive are vital for research and historical memory, but equally important is the sense of community, collaboration, and identity that has been generated through its creation. As we continue to expand and diversify the archive’s holdings, we hope to draw more community members, working-class historians, and labour movement supporters into the fold to create a participatory community that extends across Canada and North America.

To visit the archive for research/curiosity purposes, or to donate historical photographs or records related to the iwa, please email the author at

kaatzaarchives@shaw.ca.

Thanks to Letitia Henville, Annika Rosanowski, Carolyn Veldstra, and the other folks at the ubc Arts Amplifier and the ubc Arts PhD Co-op program for their endless support and encouragement. Thanks as well to the Kaatza Historical Society, particularly Pat Foster, Sue Lindstrom, Terry Inglis, Allan Lundgren, Richard Friday, and Kaden Walters. Many thanks to Claire Williams for her archival mentoring and Tina Loo for being so encouraging of her supervisee following non-traditional academic trajectories. It has been an immense pleasure to share in this labour with John Mountain, and an absolute privilege to be trusted by the United Steelworkers Wood Council to be the custodian of their history. Finally, thanks to Donna Sacuta of the BC Labour Heritage Centre for being integral to making so much happen behind the scenes, and to all the donors, supporters, and volunteers that have helped create the iwa Archive.

1. In breaking from the International and forming iwa Canada, the newly nationalized union changed its name to the Industrial Wood and Allied Workers. The acronym iwa remained.

2. Howard Zinn, “Secrecy, Archives, and the Public Interest,” Midwestern Archivist 2, 2 (1977): 20–25. Zinn had previously made similar arguments in his address to the 1970 meeting of the Society of American Archivists under the title “The Archivist and Radical Reform.” Although the manuscript for this talk is unavailable, it is quoted in F. Gerald Ham, “The Archival Edge,” American Archivist 38, 1 (January 1975): 5.

3. Jessica Pauszek, “Writing from ‘The Wrong Class’: Archiving Labour in the Context of Precarity,” Community Literacy Journal 13, 2 (Spring 2019): 52.

4. Dydia DeLyser, “Towards a Participatory Historical Geography: Archival Interventions, Volunteer Service, and Public Outreach in Research on Early Women Pilots,” Journal of Historical Geography 46 (October 2014): 93–98; Andrew Flinn, “Archival Activism: Independent and Community-Led Archives, Radical Public History and the Heritage Professions,” InterActions 7, 2 (2011): 5; Jessica Pauszek, “Preserving Hope: Reanimating Working-Class Writing through (Digital) Archival Co-creation,” Across the Disciplines 18, 1–2 (2021): 145–161; Fiona Cosson, “The Small Politics of Everyday Life: Local History Society Archives and the Production of Public Histories,” Archives and Records 28, 1 (2017): 45–60.

5. “Class consciousness” here is used in the “Thompsonian” sense of a culturally produced historical relationship, in which groups, “as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves,” in a way that is “embodied in traditions, value-systems, and institutional forms.” E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1966), 9–10. On the links between class consciousness and heritage conservation, see J.M. Crossan, D. J. Featherstone, F. Hayes, H.M. Hughes, C. Jamieson & R. Leonard, “Trade Union Banners and the Construction of a Working-Class Presence: Notes from Two Labour Disputes in 1980s Glasgow and North Lanarkshire,” Area 48, 3 (2016): 357–364.

6. In 2002 the Lumber Worker changed its name to the Allied Worker in response to both the formation of iwa Canada and the diversification of the union’s membership to include “bushworkers and janitors, chocolate manufacturers and now railway workers … bullcocks to fry cooks and everything in between.” See “It’s the First Issue of Your National Newspaper – the Allied Worker!!,” Allied Worker 67, 2 (September 2002): 1.

7. Laura Millar, “Coming Up with Plan B: Considering the Future of Canadian Archives,” Archivaria 77 (Spring 2014): 104–105.

8. For a detailed description of the process whereby Mountain, Garcia, and Lundgren connected with the Kaatza Historical Society, see John Mountain, “Digging into History,” iwa Archive Blog 1, 1 (January 2019), https://iwaarchive.wordpress.com/2020/03/29/digging-into-history-by-john-mountain-january-2019/.

9. Pat Foster, interview by author, 26 April 2022.

10. For a snappy overview of the history of the forest industry around Cowichan Lake, see Richard Rajala, The Legacy and the Challenge: A Century of the Forest Industry at Cowichan Lake (Lake Cowichan, BC: Lake Cowichan Heritage Advisory Committee, 1993).

11. The ubc Arts Amplifier is an innovative professional development initiative that supports graduate students with grant writing, project management, internships, and other programs. See https://amplifier.arts.ubc.ca/. For this author’s views on the benefit to Arts PhD students of co-op placements and career development outside of academic institutions, see Henry John, “Integrating the Public Humanities with Career Development,” Inside Higher Ed, 2 November 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/11/02/co-op-model-offers-phd-students-many-career-advantages-opinion.

12. Despite the general lack of access to the iwa historical records, both community-based and university-based historians have produced an abundance of books and articles on the history of the iwa and its members in British Columbia and Canada. These include Andrew Neufeld & Andrew Parnaby, The iwa in Canada: The Life and Times of an Industrial Union (Vancouver: iwa Canada, 2000); Allan Lundgren, iwa Canada 1-80: A 60 Year History, 1937–1997 (Duncan, BC: Duncan Printcraft, 1997); Grant MacNeil & iwa Western Canadian Regional Council No. 1, The iwa in British Columbia (Vancouver: Broadway Printers, 1971); Myrtle Bergren, Tough Timber: The Loggers of British Columbia – Their Story (Toronto: Progress Books, 1966); Sara Diamond, “A Union Man’s Wife: The Ladies’ Auxiliary Movement in the iwa, the Lake Cowichan Experience,” in B. Latham and R. Pazdro, eds., Not Just Pin Money: Selected Essays on the History of Women’s Work in British Columbia (Victoria: Camosun College, 1984), 287–296; Jerry Lembcke, One Union in Wood: A Political History of the International Woodworkers of America (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 1984); Gordon Hak, Capital and Labour in the British Columbia Forest Industry (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2007).

13. Donna Sacuta, Bailey Garden & Anushay Malik, Union Zindabad! South Asian Canadian Labour History in British Columbia (Richmond, BC: Thunderbird Press, 2022), https://saclp.southasiancanadianheritage.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/sm_Union-Zindabad-eFINAL.pdf.

14. Data for membership figures for the iwa across North America between 1937 and 1955 can be found in Henry John, “International Woodworkers of America (iwa) Locals 1937–1955,” Mapping American Social Movements Project, University of Washington, n.d., accessed 4 April 2022, https://depts.washington.edu/moves/cio_iwa_locals.shtml.

15. Anushay Malik, “South Asian Canadians and the Labour Movement in British Columbia,” in Satwinder Kaur Bains & Balbir Gurm, eds., A Social History of South Asians in British Columbia (Abbotsford, BC: University of Fraser Valley, 2022), 261.

16. S. J. Squire to E. Linder, 1 June 1949, box 79, folder 09, Correspondence and Other Administration – Local 1-85 Port Alberni (1949), iwa Local 1-80 fonds, Kaatza Station Museum and Archives (ksma).

17. Harold Pritchett fonds, rbsc-arc-1449, ubc Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver.

18. International Woodworkers of America-Canada Research Collection fonds, rbsc-arc-1779, ubc Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver.

19. Based on BC employment figures generated by Patricia Marchuk, John-Henry Harter has demonstrated that there was a 23 per cent decrease in logging employment and an 18.8 per cent decrease in sawmill employment between 1980 and 1995. See John-Henry Harter, “Environmental Justice for Whom? Class, New Social Movements, and the Environment: A Case Study of Greenpeace Canada, 1971–2000,” Labour/Le Travail 54 (Fall 2004): 105.

20. Chris Wong, “The $2 Billion Strike,” Vancouver Sun, 6 December 1986; see also Neufeld & Parnaby, iwa in Canada, 225–232.

21. “Letters from Public,” box 249, folder 2, Jack Munro Papers – 1986 Strike Records, iwa Canada fonds, ksma. For examples of these letters, as well as more detailed background on the 1986 strike, see Henry John, “‘Sometimes Strikes Are Sort of like Some Wars’: Letters to Jack Munro during the 1986 Strike,” iwa Archive Blog, 3 January 2022, https://iwaarchive.wordpress.com/2022/01/03/sometimes-strikes-are-sort-of-like-some-wars-public-letters-to-jack-munro-during-the-1985-strike/.

22. Erik Loomis, Empire of Timber: Labor Unions and the Pacific Northwest Forests (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Joan McFarland, “Labour and the Environment: Five Stories from New Brunswick since the 1970s,” Labour/Le Travail 74 (Fall 2014): 249–266; Katrin MacPhee, “Canadian Working-Class Environmentalism, 1965–1985,” Labour/Le Travail 74 (Fall 2014): 123–149; Chad Montrie, “Expedient Environmentalism: Opposition to Coal Surface Mining in Appalachia and the United Mine Workers of America, 1945–1977,” Environmental History 5, 1 (2000): 75–98; John-Henry Harter, New Social Movements, Class, and the Environment (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2011).

23. This assumption is at the root of one of the most influential pieces of literature in the field of environmental history. See Richard White, “‘Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?’: Work and Nature,” in William Cronon, ed., Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 171–185.

24. Jack Munro most famously ruffled feathers when he told a New York Times reporter, “I tell my guys if they see a spotted owl to shoot it.” This quote was then reprinted in media across North America. See Timothy Egan, “Struggles over the Ancient Trees Shift to British Columbia,” New York Times, 15 April 1990; Kathy Ramsey, “Feathers Fly as Munro Takes Aim at the Spotted Owl,” Vancouver Sun, 20 April 1990.

25. Adam Rome, The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (New York: Hill & Wang, 2013); Robert Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005), 148–160; Ryan O’Connor, The First Green Wave: Pollution Probe and the Origins of Environmental Activism in Ontario (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2015).

26. Regional Executive Board Meeting, 8 August 1972, box 125, folder 1, Minutes Executive Board Meetings Binder (1971–1975), District/Regional/National Executive Board, iwa Canada fonds, ksma; Executive Board Meeting – Local 1-217, 12 March 1971, box 39, folder 14, Minutes – Local 1-217 Executive Meetings (1971), iwa Local 1-217 fonds, ksma.

27. See, for instance, “iwa Taking Greenpeace to Court,” Nanaimo Daily News, 28 April 1998; Glenn Bohn & Kim Pemberton, “iwa Demands $250,000 in Lost Wages to Release Greenpeace Ships,” Vancouver Sun, 4 July 1997.

28. “iwa Supported Amchitka Protest,” Local 1-80 Bulletin, October–November 1971, 1, box 26, folder 9, Local Union Newspaper, iwa Local 1-80 fonds, ksma.

29. Clayoquot Sound Rendezvous, box 245, folder 09, Research Department General Files, iwa Canada Fonds, ksma.

30. iwa Greenpeace Protest (1997), Multimedia Collection, iwa Canada fonds, ksma.

31. iwa 1-80 Woodworkers Survival Taskforce (1988–89), box 52, folder 07, Bill Routley Papers, iwa Local 1-80 fonds, ksma.

32. Interviews conducted for this oral history archive are being recorded and processed. It is anticipated that they will be made available to the public in 2023. For information on the South Island Forest Accord, see Richard Watts, “Island Loggers, Tree Lovers Win Kudos for New Accord to Quiet Forest Battleground,” Times Colonist (Victoria), 11 October 1991.

How to cite:

Henry John“Working People Built This Archive: The iwa Archive and Woodworker History,” Labour/Le Travail 90 (Fall 2022): 255–267. https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2022v90.0010

Copyright © 2022 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2022.