Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Article

“La Grève de la fierté”: Resisting Deindustrialization in Montréal’s Garment Industry, 1977–1983

Abstract: On 15 August 1983, 9,500 workers from the Montréal locals of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union went on strike for the first time in 43 years. The strike became known as “la grève de la fierté” and made clear that the women working in the city’s garment factories were taking a stand against the layoffs and closures prompted by industrial restructuring and deindustrialization. However, the strike’s success was limited, revealing the extent to which the structural inequities in the garment industry had calcified along gendered, classed, and ethnic lines. The union executive had grown increasingly distant from its rank-and-file, and it was immigrant women workers who were left to organize against the flurry of closures and the corresponding decline in their working conditions. The campaign leading up to the 1983 strike, organized by the Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement, articulated a series of demands for the improvement of workplace health and safety conditions, better benefits, and more representative union leadership. With original archival research and oral history interviews, I argue that the 1983 “grève de la fierté” illustrates how the historically entrenched gendered structure of labour relations shaped the pathways of deindustrialization in Montréal’s garment industry.

Keywords: garment and textile industry, rank-and-file organizing, immigrant women, gendered labour, strike, oral history, trade liberalization, piecework, Montréal, Québec

Résumé : Le 15 août 1983, 9 500 travailleuses des sections locales montréalaises de l’Union internationale des ouvrières du vêtement pour dames se sont mis en grève pour la première fois en 43 ans. Cette grève, connue sous le nom de « grève de la fierté », montre que les femmes travaillant dans les usines de confection de la ville prennent position contre les licenciements et les fermetures provoqués par la restructuration industrielle et la désindustrialisation. Cependant, le succès de la grève a été limité, révélant à quel point les inégalités structurelles dans l’industrie de la confection s’étaient calcifiées selon les critères de genre, de classe et d’ethnie. La direction du syndicat s’était éloignée de plus en plus de sa base, et ce sont les travailleuses immigrées qui ont dû s’organiser pour lutter contre les fermetures et la dégradation correspondante de leurs conditions de travail. La campagne qui a mené à la grève de 1983, organisée par le Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement, a formulé une série de demandes pour l’amélioration des conditions de santé et de sécurité au travail, de meilleurs avantages sociaux et une direction syndicale plus représentative. À l’aide d’une recherche archivistique originale et d’entrevues d’histoire orale, je soutiens que la « grève de la fierté » de 1983 illustre comment la structure genrée des relations de travail a façonné les voies de la désindustrialisation dans l’industrie du vêtement de Montréal.

Mots clefs : industrie du vêtement et du textile, mobilisation de base, femmes immigrantes, travail genré, grève, histoire orale, libéralisation du commerce, travail à la pièce, Montréal, Québec

On 15 August 1983, 9,500 workers from the Montréal locals of the New York–based International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ilgwu) went on strike for the first time in 43 years. They hit the streets of the industrial area of Chabanel, home to Québec’s apparel manufacturing industry, in protest of a proposed collective agreement where workers would see wage rollbacks and a reduction in paid holidays.1 The overwhelming majority of the strikers were immigrant women who worked as sewing machine operators in the lowest-paid segment of the workforce. There were several issues in this dispute; however, women on the picket lines felt it was not only their livelihoods that were being threatened but also their pride and their worth as workers who had spent most of their working lives in the industry. The strike became known as “la grève de la fierté” or “the strike of pride,” and it garnered support from major feminist organizations such as the Conseil du statut de la femme, which officially stated its “unconditional support” for the strikers.2 Eight days after it began, union leadership ended the strike. The only so-called victory was in securing a wage freeze instead of the dramatic 20 per cent wage rollback that the manufacturers’ association was proposing. The outcomes of the 1983 strike reveal the extent to which the structural inequities in the garment industry had calcified along gendered, classed, and ethnic lines. State-led trade liberalization strategies beginning in the 1960s and 1970s had slashed employment in the industry, leading to massive layoffs that especially affected immigrant women in the lowest-paid segments of the workforce. At the same time, Québec’s eroded and ineffective institutions that were meant to enforce minimum labour standards in the industry were unable to exert any real pressure on employers. Organized labour, too, was facing its own crisis of confidence from both the public and its membership, as it largely failed to adapt to the growing threat of deindustrialization. Women organized their own resistance movements within the existing structures of organized labour and were consistently undermined by union officials and employers alike. The union executive had grown increasingly distant from its rank-and-file, and it was workers who were left to organize against the tailspin of closures and the decline in their working conditions. The campaign leading up to the 1983 strike, organized by the Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement (catv), articulated a series of feminist demands for the improvement of workplace health and safety conditions, better benefits, and more representative union leadership.

In this article, I focus on the catv’s activities in the years leading up to the 1983 “grève de la fierté” to examine the intersections of deindustrialization and feminist organizing in Québec. I argue that the 1983 strike illustrates how the historically entrenched gendered structure of labour relations shaped the pathways of deindustrialization in Montréal’s garment industry. To do so, I mobilize original primary-source research in newspapers, personal archives, and government documents as well as oral history interviews with former garment workers and union officials. Given the lack of secondary literature on deindustrialization in the garment industries in Canada, this article builds on the work of earlier scholars and activists who were deeply attentive to the issues facing women working in the garment industry during its decline.3 Although the language of deindustrialization had not yet entered into mainstream public and scholarly discourse, as socially engaged scholars working in the 1980s and 1990s, their analyses were grounded in women’s contemporary experiences of economic restructuring.4 Many of these earlier publications were preoccupied with the future of the labour movement at a time when deindustrialization was hollowing out much of the traditional industrial base of union membership.5 Nearly 40 years later, this article combines insights from women’s labour history and deindustrialization studies to reframe the 1983 strike within the broader context of the crisis of deindustrialization that was affecting not only the garment industry but most other industrial sectors in Canada. The 1983 strike was not simply a failure in labour organizing but rather an important moment where immigrant women articulated a series of feminist demands for decent work. Ultimately, these demands were never met, and in the decades that followed the strike, working conditions worsened and job losses accelerated. This article also adds to the relatively small body of literature that examines immigrant women’s histories of labour organizing in Canada and aims to move beyond the characterization of female immigrant workers as “unlikely militants,” or unexpected labour activists.6 Racialized, ethnic, and immigrant women organizing within the context of the catv and as active members of the picket lines show that they have always been involved in labour organizing and were often emboldened to take industrial action based on their immigrant experiences.7

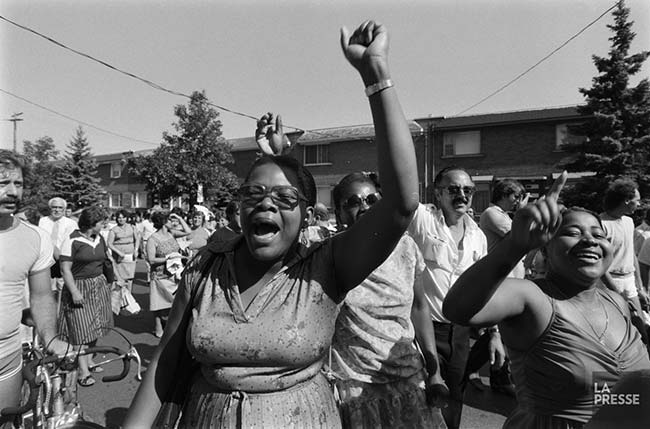

Garment workers on strike in Montréal’s Chabanel garment district.

Reproduced by permission from La Presse, 18 August 1983. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 06M,P833,S5,D1983-0278,007.

The 1983 strike also shows that deindustrialization is both an economic and a political process. Widespread closures of industrial workplaces have meant job losses for working-class people, but they have also meant the loss of unionized, well-paid jobs that supported families and communities.8 Although scholars of deindustrialization acknowledge that women have often borne the brunt of economic restructuring, the specificity of women’s experiences of deindustrialization have remained largely absent from the literature in the field.9 This article aims not only to write women’s experiences into the history of industrial closures but also to understand how the gendered structure of industrial production shaped the pathways of decline in the garment industry. The analysis will also examine how women resisted closures and the erosion of their working conditions. As oral history testimonies will show, women who worked in the deindustrializing garment industry also understood their experiences within the context of their roles as wives, mothers, and women.10 As a result, women’s organizing against closures and declining working conditions took their unpaid work into account, explicitly placing gendered concerns such as child care and maternity leave at the core of their demands.

A Note on Oral History

In the field of deindustrialization studies and in labour history more broadly, oral history interviewing has proven to be an important methodological touchstone in the broader political project of centring the experiences of working people.11 While deindustrialization and economic restructuring can often appear to be abstract processes that occur on a global scale, oral history and lived experience allows us to understand what Doreen Massey terms the “global production of the local.”12 As Steven High has shown, factory closures and relocations are not just part of the inevitable march of global capitalism; they are “willful acts of violence perpetrated against working people.”13 Recent scholarship on deindustrialization has also mobilized Rob Nixon’s concept of “slow violence,” a type of “violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”14 The slow violence of deindustrialization is often normalized as part of the status quo but has lasting impacts on individuals, families, and communities as a whole.15 Life story approaches to oral history interviewing are particularly well suited to bridging structural economic processes with the realm of individual experience, allowing us to understand the gendered impacts of deindustrialization in the workplace and in the community and household.

It is important to remember, however, that oral history and lived experience cannot be used to simply fill the blanks that traditional history leaves, because oral history interviewing is mediated and co-created by the interviewer and interviewee.16 Since the interview is always co-created, we must also acknowledge that the interview space is highly imperfect, especially in my case of interviewing across generation, language, ethnicity, and class. As Katrina Srigley, Stacey Zembrzycki, and Franca Iacovetta have pointed out, more recent feminist oral history scholarship has reminded us that there are dangers in “assuming the commonalities of gender over the differences forged by class, race, age, Indigeneity versus settler status, ability/disability, and other social categories.”17 For me, learning to listen to women’s stories and attempting to do justice to complex lives meant listening across differences.18 There were several moments in interviews where my own differences were put into relief – for example, in misunderstandings through language barriers or even my own sometimes narrow conception of what does and does not count as labour history. Additional challenges also came about in the interpretation of life stories. I am acutely aware that in the cases of a few of the discussants featured in this article, my feminist interpretations of their experiences would contradict their own understandings of their lives.19 As Joan Sangster has argued, “feminism” has often been associated with the liberation of only a narrow segment of women, often middle class.20 It is thus understandable that many working-class immigrant women did not see themselves as part of these political projects.

This article mobilizes four oral history interviews and other testimonies from archival sources to examine the gendered dimensions of deindustrialization from different vantage points but all from the perspectives of workers born outside of Canada who were engaged in production work. The lead narrator is Fatima Rocchia, a rank-and-file organizer in the ilgwu who co-founded the catv. Her interview was conducted by Leona Siaw, who produced a graphic novel on the garment industry and Fatima’s experience.21 In the early 1980s, Fatima worked at Sample Dress, one of the largest garment manufacturers in Montréal. She experienced the difficult working conditions of the garment industry first-hand and advocated for improvements in air quality, for accommodations for pregnant workers, and against subcontracting. Eventually, when Fatima was pregnant herself, she decided to take a preventive leave for fear of complicating her pregnancy as she worked in the difficult conditions of Sample Dress. In response to this request, her employer fired her, and she attempted to fight her firing in court without the support of her union. This experience emboldened Fatima to fight against the poor working conditions in the industry and the lack of backing that rank-and-file workers had from the male-dominated ilgwu leadership. I also draw on Fatima’s personal archive to retrace the catv’s organizing strategies. In addition to the interview with Fatima, this article features oral history interviews with md and Cornelia Caruso, two women who immigrated to Montréal from Italy in the 1960s and who worked in the garment industry from the mid-1960s to the 1990s.22 Their experiences of industrial labour, immigration, and child rearing in Montréal tell us a great deal about the lived experiences and costs of deindustrialization in gendered industrial work.

The narrators in this article are not exclusively women. I also interviewed Jesus Falcon, a passionate trade unionist who held various positions in the ilgwu’s executive in the 1980s and who dedicated the following decades to improving the union’s pension and welfare funds for its retired members. The differences between the interviews with men and women in this article are significant. Jesus’ interview lasted nearly four hours, and I barely had to ask a handful of questions, whereas the interviews with md and Cornelia were much shorter and required more active interviewing. The interviews with women also often included their family members, such as children and grandchildren, resulting in a much more family-based retelling of life stories. There are also key differences in the interviews based on their positions in the industry. Jesus was part of the union executive and worked as a cutter, one of the best-paid positions on the shop floor. Fatima, md, and Cornelia were all sewing machine operators, working in the lowest-paid segment of the workforce. As a result, their interpretations of working conditions and labour conflicts in the early 1980s differed strikingly, and I have highlighted these differences in the later part of this article. All interview excerpts appear in the text in their original French, and my English translations are in the footnotes.

Changing Landscapes of Gendered Labour

In the first half of the 20th century, employment in the garment industry accounted for one in every four manufacturing jobs in Montréal.23 From its very beginnings, the garment industry primarily employed women, who represented between 70 and 80 per cent of all needleworkers.24 Between 1881 and 1951, the garment industry was the largest employer of women in the province of Québec, followed by the cotton textile industry.25 In addition to being a major industrial employer, the garment industry was highly symbolic of the marginal status of the woman worker in industrial capitalism.26 Gender relations in the garment industry were highly paternalistic, constructed along lines of class, gender, ethnicity, and family to relegate women to peripheral positions in their workplaces and in their unions.27 The union that organized the majority of workers in the dressmaking sector was the ilgwu, which took a co-operative approach to its relationships with employers.28 The 1934 Loi sur les décrets de conventions collectives further solidified this spirit of collaboration, providing for the formation of a Joint Committee, a secondary administrative body with representation from employers, unions, and government, that managed collective bargaining, dues, strike calls, and the administration of benefit funds.29 According to Mercedes Steedman, the Loi sur les décrets had lasting structural consequences for gender relations in the garment industry in the province and across Canada.30 Firstly, the decrees effectively codified in law whether jobs were considered skilled or unskilled and formalized wage differentials between men and women. In the collective agreements, wages for women were on average 10 to 20 per cent less than men’s wages for the same positions.31 Payment regimes for men and women were also different: women were largely paid by the piece, and men usually worked on an hourly basis. In addition, from the earliest years of unionization, the union executive was dominated by male workers from the highest-paid segments of the workforce. Even though much of the early union organizing had been carried out by women, like Rose Pesotta and Lea Roback, their work was largely discredited within the union.32 Throughout the mid-20th century, the ilgwu’s union activism moved even further from the shop floor, where women actually worked and had “at least a minimal political voice.”33 Tellingly, an analysis of the union executive officeholders between 1910 and 1987 found that at no point had a woman ever occupied the positions of president, secretary-treasurer, or executive secretary in the ilgwu.34 This distance from the shop floor continued to shape union politics in the decades to come, and as I will show throughout this article, women had to organize outside of formal union structures.

The decades following World War II saw a series of transformations in the realms of economy, labour, gender, and migration. From an economic standpoint, it appeared that textile and garment manufacturers generally enjoyed the overall economic buoyancy of the postwar decades: domestic demand for textiles quadrupled between 1949 and 1967, and the value of clothing output increased by 33 per cent between 1949 and 1969.35 Despite these favourable conditions, the Canadian government began to pursue an increasingly liberal trade agenda, and the domestic apparel manufacturing industry saw increased competition from imported goods as early as the 1950s.36 But it was not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that the global textile industry underwent a profound shift, the effects of which were especially felt in the global clothing market. In the first half of the 1970s, exports of textiles from low-wage sources increased by 133 per cent, and exports of clothing from those same low-wage sources increased by a staggering 311 per cent.37 In response, the Canadian government legislated its first trade policy on textiles in 1971.

In her study on restructuring in the Canadian textile industry, Rianne Mahon argues that the Canadian state pursued trade liberalization and prioritized the future of its staples exports over protection of its domestic manufacturers. In particular, the textile and clothing industries were deemed marginal to the national economy, and the result of the textile policy negotiations reflected this stance.38 In an effort to intervene directly in the process of deindustrialization, the 1971 federal textile policy legislated a progressive trade liberalization strategy that gave domestic producers “breathing room” to adjust to the impending realities of global free trade.39 In practice, this breathing period was effectively an ultimatum: either modernize and improve efficiencies, or close up shop. As part of its restructuring program, the Canadian state offered relatively substantial financial support to textile producers and clothing manufacturers to invest in new equipment to keep up with import competition. In this sense, trade liberalization was combined with a direct incentive for massive investment in automation and technological change.

These global and domestic shifts changed Canadian textile policy and took a double-edged sword to employment in apparel manufacturing: if a manufacturer did not close, its investments in labour-saving technologies ultimately also led to layoffs. Trade liberalization and technological change also affected relationships between retailers and manufacturers, where global competition not only reduced Canadian manufacturers’ ability to compete with foreign manufacturers but also intensified the power of retailers over the production process.40 Job losses in the garment industry quickly followed. In 1976, approximately 94,500 Montréalers worked in labour-intensive sectors; by 1996 this number had plummeted to 54,600.41 This decline in employment was primarily attributed to the decline of the textile and apparel industries in Montréal, which represented 27,000 job losses in that period.42 Between 1953 and 1980, the total number of manufacturing jobs in the Canadian women and children’s clothing industries declined by 29 per cent.43 In the early 1980s, the recession and record-high levels of inflation led to an especially intense period of closures. Compared with other Canadian cities, Montréal was particularly hard-hit by deindustrialization, primarily because of its high concentration of labour-intensive industries like clothing, textiles, and electrical manufacturing.

While the garment industry was undergoing a profound shift, so too was the overall structure of the Canadian labour force. Following a rise in women’s labour-market participation in the postwar years, the 1970s saw a decline in the standard employment relationship and a rise in a new temporary employment relationship – both trends associated with a broader feminization of labour.44 While access to the standard employment relationship was often limited to a male breadwinner, it nonetheless reflected a troubling trend of declining union density and labour intensification.45 In this sense, economic restructuring not only threatened unionization by hollowing out employment in the manufacturing sector but also led to the creation of nonstandard, part-time, or seasonal employment in smaller and smaller workplaces, contracting work out, increased homeworking – all changes that affected women workers most intensely.46 While Canadian-born women were often able to move into higher-paid white-collar work in the postwar period, immigrant women largely took up work in the lower-paid manufacturing sectors.47

This unequal labour-market structure was also produced and reinforced by developments in Canadian immigration policy. Canada’s various immigration programs have always been designed to direct certain kinds of demographic growth and to meet labour-market needs.48 However, with the introduction of the points-based immigration system in 1967, women immigrating to Canada most commonly arrived as “dependents” and did not have access to language or job training, which further limited the types of jobs immigrant women could access.49 In a report to the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women, Sheila McLeod Arnopoulos explained that immigrant women were highly overrepresented in the lowest-paid sectors of the Canadian economy, occupying what she described as “the bottom rung of the ‘vertical mosaic.’”50

From the 1960s through the 1980s, immigrant women workers from southern Europe made up most of the workforce in Canada’s clothing and textile industries. The manufacturing sector was one of the largest employers of Portuguese and Italian immigrant women in Canada, and in 1961 almost 57 per cent of the more than 32,000 Italian women in the paid labour force in Canada were employed in manufacturing, most of them in the clothing industry.51 In 1981, 37 per cent of women who worked in manufacturing were born in Portugal.52 As scholars of southern European immigration have frequently argued, gender, migration, and labour are inextricably linked.53 In the case of Italian immigration, the migration of women and children primarily depended on men’s ability to find non-seasonal stable work abroad and frequently resulted in the temporary fragmentation of families.54 Italian immigrant families usually made their lives in urban economies that could also provide opportunities for semi- and lower-skilled women workers, who frequently began working immediately upon their arrival in Canadian cities. Although Italian community and family-based narratives of migration often emphasized women’s “natural” roles within the home, families’ material situations often meant that women had little choice but to enter the paid workforce.55 Franca Iacovetta has pointed out that the burdens of low-paid work, coupled with the massive responsibilities within households, often made it impossible for women to actively organize in unions. At the same time, other research shows that countless women born outside of Canada worked actively within and outside organized labour contexts to improve their working conditions.56

Wenona Giles’ research on Portuguese women working in cleaning and manufacturing shows that they were often radicalized through their experiences as immigrant women workers who had imagined their lives in Canada playing out much differently.57 The mid-1980s in particular saw a number of strikes led and sustained by immigrant women, including a six-week cleaners’ strike in Toronto’s financial district.58 Susana Miranda highlights that the Portuguese women at the heart of the cleaners’ strike had lived under a dictatorship and had no experience with labour organizing, yet they successfully argued that they had a right to fair wages and working conditions.59 Although immigrant women resisted the exploitation of their labour, they also bore the brunt of deindustrialization in Montréal’s garment industry. For example, between 1981 and 1996, the number of Portuguese women working in manufacturing decreased by 10 per cent, which corresponded with a rise in their occupation in service sectors like domestic labour and other informal occupations.60 In this sense, the job losses in the manufacturing sector – which was, at least to some extent, unionized – meant that women had to take jobs in even less secure, informal workplaces. As I will show, trade-induced deindustrialization set off a slow process of decline that led to widespread job losses as well as a deterioration in the working conditions in the shops that remained.

The Impacts of Deindustrialization on Women in the Garment Industry

The legacies of poor working conditions in the Canadian garment industry, especially in the early 20th century, have been the subject of numerous studies. However, poor working conditions and structural problems were experienced with particular intensity as factory closures ramped up. In the context of the global “race to the bottom” that accompanied free trade in textiles and clothing, industrial decline went hand in hand with labour intensification and worsening labour conditions in existing factories.61 In her interview, Fatima Rocchia sums up her experience as a sewing machine operator viscerally: “Moi je venais d’une dictature au Portugal; à l’époque on avait la dictature Salazar … Et c’était pire qu’au Portugal, les conditions de travail, sur la rue Chabanel.”62 She goes on to explain how employers’ constant search for profit often left workers in situations perilous to their health and safety:

Eux, c’est le cash. Tu sais, c’est juste le cash qui compte, il y a rien [d’autre]. J’ai vu des femmes tomber par terre. Il faisait chaud, on arrivait avec une chaudière d’eau froide pour l’envoyer dans la face. C’étaient des conditions comme ça, le travail. Là j’en revenais pas, j’ai dit: “Appelle l’ambulance, quelque chose, appelle son mari” tout ça. Ils ont dit: “non, non, non. Elle va mieux, là, elle va finir la journée.” Ils l’ont pris, elle s’est relevée, ils l’ont mis à la machine à coudre, et elle continuait à travailler. C’étaient des conditions écœurantes. À un moment donné j’avais fait venir le ministère du travail faire un test sur la qualité de l’air et sur la chaleur parce que c’était fou. Il y avait toutes les presses pour presser les vêtements, et ça c’était tout à vapeur chaude. Il y avait les fenêtres ouvertes mais dans toute la manufacture ils chauffaient tout le temps pour fournir la vapeur chaude. En plus de faire 44 degrés dehors, on avait la température en dedans.63

One way that employers maximized profits at the expense of working conditions was by tying their employees’ wages to the amount of clothing they produced. When Cornelia Caruso first started working at Hyde Park, a notorious menswear factory in downtown Montréal, she was paid hourly. However, during the two years she worked there in the mid-1960s, the company transitioned from paying its employees hourly to paying them by the piece. Although piecework had been a common system of remuneration ever since the earliest days of industrial garment manufacture, shifting to piecework payment regimes was common in the organization of work to cut costs in the face of economic restructuring. According to Mahon, between 1949 and 1969, the clothing industry underwent a period of adjustment: employment rose by a modest 6 per cent, whereas the value of output in the industry increased by 33 per cent. Mahon argues that much of this had to do with changes in managerial style and input, which included a widespread shift toward piecework payment regimes.64

This switch was also highly emblematic of the intensification of work that was taking place in the garment industry in the mid-to-late 1960s. Cornelia and md had complicated relationships to being paid by the piece. Here, Cornelia explains how the piecework system worked for her on a daily basis:

Oui oui chaque semaine on faisait le— parce que je travaillais à la job, on faisait le compte des étiquettes que je faisais, il y avait deux prix, parce que moi je faisais le stitch ici dans les jackets d’hommes. Si je faisais un, c’était un prix, si je faisais deux c’était un autre prix, c’était plus cher.65

By doing different sewing stitches on different garments, operators collected tickets. The more pieces workers sewed, the more tickets they collected, and the more money they made. In this sense, workers’ productivity is directly tied to their wages, resulting in constant pressure to work quickly. In an industry with increasing unemployment rates, workers often had little choice but to remain in workplaces with poor working conditions. Piece rates also force operators to work as fast as possible, but the faster they work, the lower the prices are set for the pieces because they take less and less time to make. In addition to this downward pressure, piece rates also created workplaces that were often rife with conflict. Jesus Falcon elaborates:

Parce que, il faut comprendre que, à part les tailleurs qui travaillent à l’heure, tous les autres travaillent à la pièce. Travailler à la pièce, dans une industrie saisonnière, ou vous changez deux trois fois par jour les modèles, et après ça ils les font dans d’autre sections, il y a pas un dieu qui est capable d’établir un prix fixe qu’on peut négocier. Donc, c’est à chaque jour, c’est une négociation. Donc, une chance d’avoir la chicane. Y’a des travaux plus vites que d’autres. Mettre un col c’est pas la même chose que faire la couture sur le côté, une couture droite, là. Donc y’en a des travails qui prennent plus de temps que d’autres, mais y’en a aussi des gens qui sont pas assez vite, ou qui bougent pas assez. Donc, il faut envoyer des gens les aider. Qui est-ce que vous prenez pour faire ça? Bon, ben, le meilleur travailleur. Mais le meilleur travailleur, il est pas content, parce que … Mettons qu’il fait des colliers. Et il y’a trente paires de trucs, et qu’il va vite. Mettons que vous l’envoyez faire une manche, un poignet. Ben c’est pas la même chose. Comme il connait pas le truc, il va moins vite. Et en attendant qu’il s’habitue, mais il est là juste pour donner un coup de main. Donc il peut être là 3–4h, une journée. Donc pendant ce temps là il gagne pas le même argent que quand il fait sa job. Ça fait la chicane. Donc … Y’a une espèce de frustration générée, et ils veulent que le syndicat … Une des choses, c’est qu’ils voulaient que le syndicat règle ça.66

Not only did piecework make it difficult to set fair and consistent prices, but it also clearly undermined solidarities among workers and actively discouraged them from helping each other. A report by the Ligue des femmes du Québec further argued that piecework systems heightened tensions between immigrant and non-immigrant workers.67 The report exposed the major issues facing women in the garment industry. The Ligue des femmes interviewed 139 women for this report, identifying a key set of issues that respondents highlighted: the piecework system, sexual harassment, abusive and controlling management, the search for profits above all else, and the “double emploi” of work outside the home and inside the home.68 Importantly, the report signalled the growing practice of employers threatening closures to force workers to fear for their jobs and to keep them producing at the highest possible levels.69

In another report, Sheila McLeod Arnopoulos further argued that the astoundingly high yearly turnover rate, 35 per cent, was in itself a testament to the poor working conditions and the degree to which workers will only tolerate their situations for as long as they have to. The study largely echoed many of the issues identified by the Ligue des femmes’ report and recommended that provincial legislation be bolstered and better enforced to materially improve conditions in the industry. But crucially, what Arnopoulos’ report also identifies is a growing problem with the institutions that were meant to regulate the industry. A combination of weak inspection systems, absent mechanisms for fining employers, and a limit on the number of months that employees can be reimbursed for back pay meant that it was becoming easier and easier for employers to circumvent the minimum wage legislation.70

Feminists at the time were also raising alarm bells regarding the resurgence of homeworking in the industry. Homeworkers have been an integral, yet hidden, labour force in the garment industry in Montréal and across North America ever since its early industrial beginnings.71 The sweated labour of the 19th century’s garment industry relied heavily on women who sewed in their homes, but homeworking briefly decreased in the early to mid-20th century. As Laura Johnson and other feminist scholars argue, its resurgence in the second half of the 20th century represented a rolling back of working conditions to the early industrial era of clothing manufacturing.72 Subcontracting allowed manufacturers to offload costs directly to the workers through the practice of sending sewing work to people who worked from their homes. Homeworkers had to buy their own sewing machines and were responsible for their upkeep.73 Homeworking is a particularly gendered regime of work; women work long hours to make very little money, and because they are working in their homes, homeworking is often seen as compatible with housework and childcare.74 Homeworking was unregulated and under the table, and as a result, homeworkers experienced some of the worst working conditions in the industry and were paid dismal wages. Roxanne Ng’s study on homeworkers in Toronto reported that a homeworker would make about $2 for sewing a skirt that would retail for more than $200 in stores.75 The resurgence of homeworking and piecework were just some of the ways that employers attempted to cut costs and stay open amid worsening economic conditions. In this sense, deindustrialization involved a significant deterioration in working conditions and wage rates. Yet women employed in the deindustrializing garment industry resisted these changes.

Jobs Worth Saving

Although labouring in the garment industry was becoming increasingly difficult, workers were keen not only to save their jobs but to improve the conditions under which they worked. In fact, in every interview, garment workers would almost invariably address the common misconception that work in apparel manufacturing was a “bad job.” Despite the fact that labour organizers and other industry activists have largely condemned piecework, it was possible to make quite a large amount of money if one was particularly fast, was experienced, and had a lot of seniority in their shop. For md, piecework was both a path to making more money and a deeply stressful way to work. She describes what it felt like for her to improve and work faster and faster: “Après, on a commencé ça, à travailler piecework, gagner quelques dollars de plus, améliorer la situation … on a commencé le salaire a monté à 50 piasses par semaine. 50, 60, 70, 80, ah mon dieu c’est la fin du monde, c’est une grande paye, 70 piasses? Ah, c’est la fin du monde.”76 md’s sarcasm here is telling: on the one hand, she recognizes that 70 dollars a week does not seem like a lot today. But it was such a large amount of money for her at the time that, as she puts it, it was “the end of the world.” For md, piecework was a pathway to increasing her paycheque and improving her family’s economic situation. Although women’s wages are often constructed as “supplemental” to men’s wages, immigrant women from southern Europe were key breadwinners whose employment in the garment industry supported their households during periods of seasonal unemployment for their husbands.77 Immigrant men often worked in dangerous and accident-prone industries, so women’s wages were also crucial to support families with an injured breadwinner.78

Even those who worked at hourly rates felt that their wages were decent. Fatima Rocchia recalled that her wages were on par with her husband’s:

On pouvait pas dire qu’on était si mal payées que ça, parce qu’en 1980 quand je sortais pour l’accouchement de ma fille, j’avais plus de dix dollars de l’heure. On avait une parité, presque. Il y avait beaucoup de femmes, de jeunes femmes aussi, de mon âge – à l’époque j’avais 25 ans, j’ai accouché de ma fille à 25 ans – et les conjoints étaient beaucoup dans la construction. On avait un équivalent de salaire d’un plombier à l’époque. Les gars qui travaillaient dans la construction, dans la plomberie, on avait la même parité de salaire. On était bien payées, celles qui étaient syndiquées, celles qui étaient dans les comités … on appelait ça des comités paritaires. Il y avait un comité paritaire pour le vêtement. C’était tout de même pas pire. C’était pas la mer à boire, mais quand je compare aujourd’hui, avec le salaire minimum, quand je repensait à tout ça, c’était quand même des bons salaires, et là ils ne voulaient pas nous le payer.79

As Rocchia explains above, her salary should have been a good one, but by the early 1980s the collective agreement and its wage standards were frequently circumvented by manufacturers. These violations of the collective agreement were largely tolerated by the Joint Committee, which was the supposedly neutral third-party board meant to enforce the decreed collective agreement for the dressmaking industry. Just a few years earlier, however, it had been placed into government receivership as a result of its inability to enforce even the minimum labour standards in the industry.80

Indeed, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the ilgwu was in a veritable crisis. Not only was it facing increasingly difficult economic conditions with the onset of progressive trade liberalization, but it also faced a crisis of confidence from its membership and the public at large. In February 1976, the Fédération des travailleurs du Québec (ftq) launched an investigation into the ilgwu in response to complaints from its membership, which included allegations of collusion with employers.81 In November of 1980 the provincial organized crime watchdog, the Commission de police du Québec relatif aux enquêtes sur le crime organisé (ceco), was assigned to dedicate all of its resources to an investigation into garment manufacturers, contractors, employers’ associations, unions, and the Joint Committee.82 Although the ceco inquiry did not conclude until 1984, as early as 1981 it unearthed a major scandal, finding that the ilgwu had erased a debt of $273,688 to the union’s welfare funds from a garment manufacturer, Raymond Boisvert. This transaction, allegedly made to keep the shop unionized with the ilgwu, became known as the Affaire Boisvert.83 In the wake of multiple scandals involving the institutions that were meant to protect them, rank-and-file workers began to organize their own movements against their union’s lack of militancy, employer abuses, and plant closures.

Rank-and-File Resistance to Deindustrialization and Patriarchal Union Leadership

In June 1981, about 6,000 members of the ilgwu refused to enter 50 of the city’s garment shops in protest of manufacturers systematically circumventing the industry-wide collective agreement by sending work to non-union shops and homeworkers.84 The walkout paralyzed about 60 per cent of the city’s clothing manufacturers, and union members toured media outlets on the Friday afternoon before going to Labour Minister Pierre Marois and the general secretary of the ftq, Fernand Daoust. Protest signs read “Contre les divisions,” “Non au travail à domicile!,” “Le chômage profite aux boss,” “While we can let’s fight now.” Workers demanded a union assembly and refused to go back to work unless the problems associated with subcontracting to non-union shops were resolved.85 However, the workers who staged the walkout were swiftly ordered back to work by ilgwu leadership, who also denied their request for a union assembly, after the employers signed agreements to reduce or put an end to “undeclared work” in the industry.86 This commitment from leadership proved to be empty, as manufacturers continued to circumvent the collective agreement, and rank-and-file workers would become increasingly doubtful of union leadership’s ability to enforce even the basic labour standards outlined in the collective agreement.

The Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement was on the forefront of rank-and-file organizing against plant closures. The catv was formed in 1980 by a multiracial and multiethnic coalition of immigrant sewing machine operators who were dissatisfied with the inaction of their union in the face of mass closures and job losses. Fatima Rocchia, a Portuguese sewing machine operator and ilgwu shop steward, was one of the catv’s co-founders. At the same time as trade liberalization slashed employment in Montréal’s highly feminized labour-intensive industries, feminist challenges to unions sought to expand what were considered legitimate union issues. In addition to fighting for fair wages, unionized women began to organize around issues such as sexual harassment, maternity leave, and child care.87 As Patricia McDermott and Linda Briskin have argued, these feminist encounters with the labour movement also took on a symbolic importance, representing an important moment for “re-visioning” what the labour movement could be, and placed a great deal of scrutiny on the organization of power in unions.88 The trajectories of the garment industry and the feminist movement intersected frequently at this time, with women’s organizations and publications frequently attempting to draw attention to the industry’s poor working conditions and to the failures of the garment unions to protect their workers.89 The catv crystallized against the backdrop of the long-time gendered division of labour that had organized apparel manufacturing for decades. The catv organized a secretive network of communication to organize meetings and settled on a strategy to “take [their] union into [their] own hands.”90 Its assessment of the ilgwu was scathing, resulting in the accusation that it was an “anti-democratic union” that “forces its members to defend themselves.”91 The catv affirmed that it is “only workers organized at the base that can win victories against the employers.”92 They were also closely monitoring the wave of closures that was facing the industry. A catv pamphlet titled “Fermetures? Mise-à-pied? Chômage” linked the closures to several factors, including the resurgence of homeworking, federal government policies, clothing imports, investment in labour-saving technologies, and strategies to encourage workers to accept pre-retirement benefits.93 They demanded a general assembly for all workers in deindustrializing industries, effective legislation on plant closures and mass layoffs, an employment stabilization fund, the abolition of homeworking, and that employers be prevented from sending work to non-union shops.

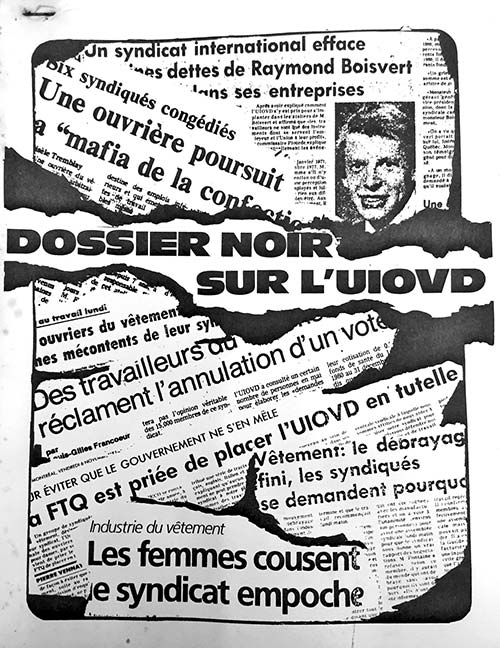

The Dossier noir sur l’uiovd. Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement, “Dossier noir sur l’uiovd,” 4 November 1981.

Personal papers of Fatima Rocchia. Reproduced with permission.

The centrepiece of the catv’s strategy was to develop a pamphlet for the 1981 ftq Congress and propose a resolution for the ftq to place the ilgwu under trusteeship. On 4 November 1981 the catv published the Dossier noir sur l’uiovd (The Black Book on the ilgwu), a scathing report highlighting the union’s corruption, its leadership, and the plight of workers in an industry operating under the constant threat of deindustrialization. According to newspapers, the Dossier noir had the effect of a bomb in the industry. It laid bare the catv’s main grievances against the union and the structural issues in the industry. It was prepared in advance of the 1981 convention of the ftq by a group of twenty unionized ilgwu workers.94 The Dossier noir was distributed to garment workers, labour organizers, and other community activists.95 It made use of original reporting, union and government-generated statistics, and most centrally, workers’ testimonies to illustrate the biggest problems identified by workers. catv president Mireille Trottier explained that workers were accusing the ilgwu not only of not attempting to solve any of the problems with the industry but also of collaborating with employers. The catv denounced the union’s lack of militancy, chauvinism toward women, and discrimination on the basis of ethnicity and race.96

Fatima Rocchia personally experienced this kind of discrimination on several occasions as the shop steward at Sample Dress. For her, the ramping up of closures was directly tied to the union leadership’s cozy relationship with employers:

J’étais la représentante syndicale de 600 femmes. On parlait à peu près 20 langues. On était toutes des femmes immigrantes là-dedans … Et petit à petit ils préparaient les fermetures des usines une après l’autre. Et c’était tout ça que nous on revendiquait. Il y avait des manufactures qui fermaient avec la complicité du syndicat, et c’est ça qu’on avait dénoncé. C’est pour ça qu’on avait fait le Dossier Noir et qu’on a sorti toutes sortes de choses … Ils ne travaillaient pas pour les intérêts [des travailleuses] souvent … Quand on les faisait venir dans les manufactures [le syndicat], ils parlaient avec le boss, ils se serraient la main et ils ne venaient pas me voir.97

As the shop steward at the time, Fatima was frequently left out of conversations between the union and her employer. Such occurrences, shaped by the gendered structure of the ilgwu executive and the industry as a whole, were deeply frustrating for concerned workers like Fatima and fuelled their determination to shake up the status quo in the industry.

Gendered concerns about health and safety conditions were at the core of the Dossier noir. The very first section of the Dossier noir denounced the way that the collective agreement characterized pregnancy as an “illness” and how, in many women’s experiences, pregnancy would lead to job loss. One worker provides a testimony in the Dossier noir: “I still needed to produce even if my energies diminished, even if I was exhausted. I couldn’t feel my legs and my back. I talked to the other women and they told me that a lot of women miscarried in the garment industry because of the difficult working conditions.” The Dossier noir also raised concerns about aging workers. Restrictive conditions related to accessing pensions meant that few workers were able to receive their pensions and were thus unable to retire. The document also noted that the conditions to access the pensions were difficult to attain for women in particular, because of the need to have worked for several consecutive years, which for women were often interrupted by leaves of absence to perform the gendered and unpaid labour of child care and other types of caregiving. The Dossier noir shares the testimony of Nadia, who had immigrated to Canada eighteen years before and was nearing retirement at age 63. She was laid off after her plant closed and couldn’t find work because she was aging and slowing down. Because the union required twenty years of work, and ten consecutive years before retirement, Nadia was not allowed access to a pension. The pressures resulting from deindustrialization thus restricted older workers’ access to pensions, which was even more difficult for immigrant women. According to the testimony in the Dossier noir, Nadia had no other choice but to take on work at home at piecework rates. The demands made in the document reflected the priorities of the immigrant women who were behind writing it. Research on immigrant women’s community organizing has shown that while white feminists tended to focus on economic independence from men, child care, equal pay, and unionization, immigrant women placed workplace health and their family responsibilities at the heart of their organizing priorities.98

The Dossier noir was a direct appeal for the ftq to intervene, and it included a resolution to be presented at the ftq Congress in late November of 1981, requesting that the ftq place the ilgwu into receivership. In interviews with local media, organizers with the catv argued that it was the responsibility of the trade union federation to which they were affiliated to ensure that their union be able to defend their living and working conditions.99 From the very beginning of the Congress, the ftq was forced to publicly debate the plight of the garment unions and the problems faced by the industry, which eclipsed many of the other issues on the agenda for the day.100 After two hours of bitter public debate, the resolution ultimately failed and the ftq refused to put the union into receivership.101 Instead, the ftq committed to yet another investigation into the ilgwu, citing that this option was far less “odious” than receivership.102 Although they were disappointed, catv members were not surprised by the result. They considered the two-hour public debate a victory, since it forced the ftq and its membership to consider the plight of the garment industry in a sustained way.103

In the wake of the 1974–75 Cliche Commission on Québec’s construction unions, which placed those unions under government receivership, members of the catv were keen to avoid government involvement and instead wanted the issues within the ilgwu to be addressed within the labour movement itself.104 In fact, one of the group’s central concerns was the stability of the labour movement, and they were sensitive to the overall anti-union sentiment at the time:105

Nous ne voulons pas d’un autre salissage du mouvement syndical comme il y en a eu contre les travailleurs de la construction. Nous voulons rester syndiqués. Nous voulons demeurer avec la ftq, mais il faut que la ftq agisse face à l’uiovd, et nous avons besoin du soutien de la ftq et de tous les syndicats qui y sont affiliés pour parvenir à faire le grand ménage dans l’uiovd.106

The relationship between deindustrialization and the state of the labour movement is also elucidated in the response from the other garment workers’ union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (acwa), which also presented a resolution at the ftq Congress that year. Its resolution condemned the ceco investigation into organized crime in the industry and urged the government to end the inquiry by the end of December that year. The union argued that the inquiry was based on unfounded rumours and that the interventions in offices and union members’ homes were unreasonable and unjustified. Importantly, though, the acwa was concerned about the timing of the inquiry and the heightened threat of deindustrialization in the early 1980s. It argued that the garment industry “suffered and continues to suffer economic losses” and, “because of this inquiry, the industry’s reputation will continue to decline in the public’s eye, which will cause further layoffs of garment workers.”107

In March 1982, the ilgwu underwent a major restructuring, around the same time that the ftq launched the investigation that it had promised at the previous year’s Congress. The new union leadership, headed by former cutter Gilles Gauthier, was viewed with skepticism by the more militant elements of the ilgwu, including the catv and the women’s committee. They largely saw these developments as “more of the same,” accusing the new leadership of quashing militancy among its rank-and-file. Just three weeks into their mandate, the new leadership of the union sought to disband the catv-associated women’s committee and appoint its own women’s committee.108 The catv spokesperson saw the new leadership’s attempt to destabilize the women’s committee as a direct threat against the union’s more militant rank-and-file members.

La Grève de la fierté: The 1983 Garment Industry Strike

The new ilgwu executive would soon face a massive challenge. On 3 August 1983, the three-year ilgwu contract expired. The employers proposed a 20 per cent wage rollback, an increase in the workweek to 40 hours from 35 hours, and a reduction in workers’ benefits. Employers complained that they could not afford the current wage scale because of competition from imports and non-unionized domestic manufacturers, who on average paid one dollar less per hour.109 Ten days later, union leadership called a general meeting to discuss the employers’ association’s contract offer. According to one publication, the 5,500 members in attendance at that meeting “roared their displeasure” with the employers’ proposal.110 In an overwhelming show-of-hands vote, the members in attendance voted 99 per cent in favour of a strike.111 On 15 August, 9,500 workers from the Montréal locals of the ilgwu went on strike for the first time in 43 years. According to several accounts, the ilgwu executive was not particularly keen on the idea of striking at that time. Fatima Rocchia remembers that the groundswell of frustration from the membership fuelled the catv’s organizing work:

C’était par le Comité d’action que la grève a été organisée parce que là on se battait contre le syndicat et tout. On n’avait pas l’appui du syndicat. On n’avait pas l’appui du tout. À un moment donné ils ont essayé, ils se sont greffés, ils sont arrivés avec les affiches et ils nous ont dit: “bon ben, on va vous fournir les affiches et toutes ces choses-là.” C’était vraiment les militantes, les gens qui étaient des militantes.112

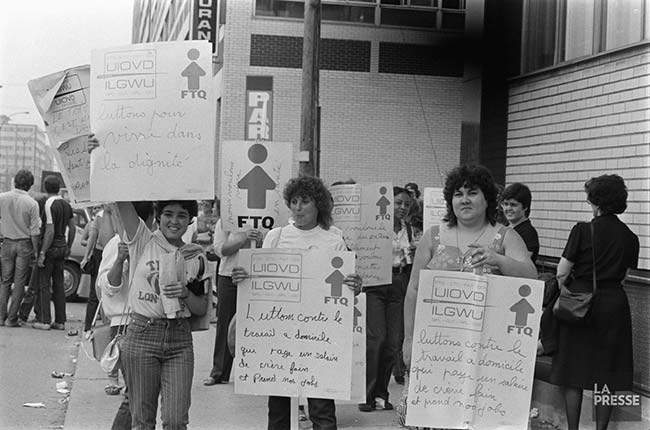

Women on picket lines in Montréal’s Chabanel garment district. The messages on protest signs mention health, safety, and dignity, as well as concerns about homeworking.

Reproduced by permission from La Presse, 18 August 1983. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 06M,P833,S5,D1983-0278,007.

For Fatima, it was the rank-and-file members of the union who were the real catalysts for the strike, and the union leadership followed. Gilles Gauthier, the union’s new Québec president, said in an interview, “We’ve accepted low wages for the last 35 years to help the industry. Now we want the industry to help us. This strike must go on in the name of pride and decency. It is no longer a matter of money.”113 The wage rollback proposed by the employers was unacceptable to rank-and-file workers and union leadership alike. On the picket lines, workers were demanding a dollar-an-hour wage increase. Employers framed the union’s demands for pay increases as unrealistic in the context of competition from cheaper imports and non-union subcontractors, arguing that a dollar-an-hour pay increase would trigger massive layoffs.114

On 20 August 1983, the ilgwu executive recommended that the membership accept a new contract proposal that would freeze workers’ wages until March of the next year, when there would be a 50-cent increase for the lowest-paid workers and a 25-cent increase for workers in higher wage groups.115 Importantly, the issues around working conditions and benefits remained unsettled. The union executive knew this was a bad deal: “I’m not trying to sell them a good contract, but it’s the best we could get,” Gauthier said.116 At the first meeting since the beginning of the strike, workers loudly rejected the contract proposal. The meeting was meant to be for a vote on whether to end the strike, but the rowdy show-of-hands vote was inconclusive and the executive needed to call another meeting, this time for a vote by secret ballot. Three days later, the union held the official vote to accept or reject the contract proposal. A little over 6,000 of the 9,000 ilgwu members voted at nine polling stations across Québec.117 The vote was 3,085 to 3,024 in favour of accepting the contract offer – a margin of only 61 votes. In fact, the number of spoiled ballots was double the number of votes that determined the outcome.118

The day after the secret-ballot vote, workers were forced to return to work. A group of 200 workers were deeply unhappy with the new contract, and they blamed their union for having failed to make gains regarding their health and safety concerns. One anonymous worker sums it up particularly well:

Our eyes are opened this time. Our own union is taking us for a ride. They’re telling us to go back to work now. Then what did we strike for? It’s been the same crappy thing for 43 years with this union. When we go back, management will open the doors and tell us, “Come in, you animals.” I’ve been a presser for eight years. Two weeks ago it was 110 degrees in our shop, and we have no air conditioning. I know what lousy working conditions are.119

The frustration that this worker expresses toward the outcome of the strike is highly representative of the profound ambivalence that the strike generated. It was clear that the industry was at the beginning of a freefall, and striking seemed like the last option to make any gains in terms of working conditions.

In the immediate aftermath of the strike, catv members were systematically purged from the union and from their jobs.120 Fatima was laid off and effectively blacklisted, preventing her from working elsewhere:

Je savais, j’ai continué à faire des démarches, et mon nom était affiché partout. C’était impossible de me trouver du travail en couture. Impossible. Rocchia c’est le nom de mon conjoint, et à l’époque j’ai réessayé de prendre mon nom de fille. Écoute, même ma photo était affichée partout, partout. On était toutes affichées. Il y avait un monsieur qui m’avait dit qu’il avait vu ma photo. Lui il m’avait expliqué qu’il est allé travailler dans un autre endroit; ils ont les bureaux de réception quand tu arrives dans une manufacture. Ils avaient plein de photos. Elles étaient toutes là. Il y en avait partout. Les gens qui venaient chercher du travail, là ils comparaient la photo. Ils ne te laissaient même pas remplir la demande.121

Organizers within the catv paid a high price for attempting to resist the decline in their working conditions. In my conversation with Jesus Falcon, who was a member of the ilgwu executive during the 1983 strike, we discussed some of the difficult questions that came up for union leadership at that time. In his view, the ilgwu was in an impossible position. The flurry of plant closures deeply affected the union’s ability to organize at this time, and the leadership felt the impacts of the decline in their membership profoundly:

Aussi, le membership, en descendant, on était pas capable de garder autant de monde. Y’a fallu couper … Donc, oubliez pas qu’un syndicat … Quand on a rentré on avait 30 agents d’affaires, on avait 6–7 employés de bureau, tous les employés de bureau, il faut leur faire une paye à chaque semaine, on est une compagnie par nous-même, là. Le syndicat y’avait pas mal dépensé l’argent, quand on a pris la place là, y’avait plus de dettes qu’il y avait de l’argent. Une des reproches qu’on faisait au syndicat, que moi je faisais au syndicat, c’est que y’avait une politique que quand ils partiraient il y aurait plus d’argent. On leur disait il fallait qu’ils augmentent la cotisation syndicale de 10 cents par mois … Parce qu’ils nous ont présentés les états financiers, la caisse y’descendait continuellement, donc … c’est ça.122

The membership of the ilgwu was declining largely in step with the increasing pace of closures from the late 1970s and into the 1980s and 1990s. In 1976, ilgwu membership stood at about 17,500 workers. By 1981, this figure had dropped to 13,000, and by 1985 it had plummeted to 7,500 members.123 Declining membership meant a decline both in the union’s coffers and in the union’s ability to be able to organize new shops:

Arrivait le libre-échange, la modernisation, les robots pis ainsi de suite, et le manque de … les gens qui vieillissaient, tout ça c’est arrivé comme au même temps. On était pas capable d’organiser. On a beau essayé, autant d’argent qu’on pouvait, même plus, dans le département d’organisation, y’ont jamais rien organisé. Ils ont jamais vraiment organisé quoi que ce soit. Pis bien souvent, c’est des anciens syndiqués qu’on rencontrait dans les places non-syndiquées. Mais il y avait un esprit que c’est la faute du syndicat, cet esprit de frustration, envers le syndicat, qu’il leur donnait pas une bonne job, qu’il faisait pas ci, qu’il faisait pas ça.124

It was clear in our exchange that Jesus really struggled with the frustration that was directed at the union. There was also an overall undertone of resignation: in the face of deindustrialization, Jesus explained, the ilgwu executive would just take care of the membership that the union still had, by providing the best pension, health insurance, and services they could.125 Jesus attributed the situation to several problems all happening at the same time, a perfect storm that led to the industry’s demise. What is crucial to keep in mind, though, is that caught in the middle of this “perfect storm” were thousands of working women. From Fatima Rocchia’s perspective, it felt more like the union was giving up on its members: “l’industrie de l’époque, elle était déjà en déclin grave. C’est pour ça qu’ils se sont fiché de nous, les conditions qu’on avait. Ils se sont fiché des travailleurs.”126

Conclusion: A Feminist Resistance on Multiple Fronts

In this article, I have highlighted the early 1980s as a flashpoint in the history of the Canadian garment industry, showing that deindustrialization was bound up in the gendered and ethnic structure of labour relations in the industry. The flurry of closures in the 1980s was precipitated by a shift in Canadian trade policy that aimed to gradually open up the garment industry to import competition. While clothing manufacturing was always highly feminized, immigrant women from southern Europe made up the vast majority of the industry’s workforce in this period. They took a great deal of pride in their work as essential breadwinners for their families and were often lifelong workers in the industry. Increased import competition and subsequent cost-saving measures by employers led to the intensification of their work and the erosion of hard-won minimum standards in their working conditions. These developments resulted in a staunch campaign of resistance from rank-and-file immigrant workers through the Comité d’action des travailleurs du vêtement. The catv catalyzed a movement within the rank-and-file of the ilgwu that fought deindustrialization on two fronts: it elaborated a feminist critique of the male-dominated union leadership at the time, as well as against their employers and the government institutions that were meant to regulate the industry. Workers in the catv not only fought to save their own jobs but also wanted to improve them, and they campaigned on a series of feminist demands to improve health and safety conditions and fight the gendered discrimination that was endemic in their workplaces and in their union. The catv’s organizing strategies and priorities reflected the fact that they were led by and represented a coalition of multiethnic sewing machine operators whose jobs were the most vulnerable to the pressures of deindustrialization. The outcome of this resistance – that workers largely failed to secure any major gains in their wages or working conditions and that a number of the catv activists were subsequently blacklisted – shows the extent to which gendered discrimination had calcified in the garment industry.

While previous scholarship casts the 1983 “grève de la fierté” as a strategic failure of labour organizing, I understand the catv’s organizing as a crucial moment where immigrant women resisted closures and eroding working conditions in an industry that was on the decline. As Susana Miranda argues, immigrant women have consistently defied their characterization as “unlikely militants” and, through their participation in labour organizing, have “enlarged the definition of who could belong to an active and militant working-class.”127 While it is clear from the women’s labour historiography that women (and especially immigrant women) have borne the brunt of economic restructuring, the field of deindustrialization studies has largely failed to take these experiences into account.

In this article, I have attempted not only to write women’s experiences into the history of industrial closures but also to argue that a feminist lens can reveal something unique about deindustrialization. By historicizing the gendered structure of industrial production, we get a sense of the unique pathways that deindustrialization took. Bringing women’s labour history into direct conversation with the insights of deindustrialization studies allows us to understand how the slow violence of deindustrialization intersected with and amplified women’s experiences of class, gender, ethnicity, and immigration status. This means probing the interactions between regimes of paid and unpaid labour. At the same time, processes of deindustrialization coincided with broader developments in women’s and gender history, including the women’s movement of the 1970s and 1980s. Taken together, these insights paint a more complicated and complete picture of industrial work beyond the paradigmatic male worker.

A very warm thank you to all those I interviewed, for sharing their experiences and wisdom for this project. Thanks also to Mary Anne Poutanen, Steven High, and Lachlan MacKinnon for their comments on earlier versions of this article. Thanks also to Leona Siaw, who generously provided access to archival and interview materials, and to the Labour/Le Travail editorial team and reviewers who provided incredibly helpful comments on my initial submission. This article is based on a chapter from my master’s thesis, which was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (sshrc).

1. Carla Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women in the Clothing Trades: Homework and the 1983 Garment Strike in Canada,” Studies in Political Economy 22, 1 (1987): 42.

2. Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women,” 41.

3. See Roxana Ng, “Racism, Sexism, and Immigrant Women,” in Sandra D. Burt, Lorraine Code, and Lindsay Dorney, eds., Changing Patterns: Women in Canada, 2nd ed. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993), 279–308; Ng, “Restructuring Gender, Race, and Class Relations: The Case of Garment Workers and Labour Adjustment,” in Sheila Neysmith, ed., Restructuring Caring Labour: Discourse, State Practice, and Everyday Life (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2000), 226–245; Ng, “Work Restructuring and Recolonizing Third World Women: An Example from the Garment Industry in Toronto,” Canadian Woman Studies 18, 1 (1998): 21–25; Ng, “Homeworking: Dream Realized, or Freedom Constrained? The Globalized Reality of Immigrant Garment Workers,” Canadian Woman Studies 19, 3 (1999): 110–114; Laura Johnson, The Seam Allowance: Industrial Home Sewing in Canada (Toronto: Women’s Press, 1982); Carla Lipsig-Mummé, “Canadian and American Unions Respond to Economic Crisis,” Journal of Industrial Relations 31, 2 (1989): 229–256; Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women”; Lipsig-Mummé, “The Renaissance of Homeworking in Developed Economies,” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 38, 3 (1983): 545–567.

4. Katrina Srigley, Stacey Zembrzycki, and Franca Iacovetta very poignantly argue for the political importance of acknowledging and valuing earlier scholarship. They point out that the requirement for academic programs to produce original work “has engendered training methods that can encourage a culture of discounting or forgetting elders. … One result is frequent dismissal of, or disregard for, the work of earlier scholars.” Srigley, Zembrzycki, and Iacovetta, eds., introduction to Beyond Women’s Words: Feminisms and the Practices of Oral History in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Routledge, 2018), 7.

5. Carla Lipsig-Mummé wrote an article about the 1983 strike just a few years later for Studies in Political Economy. At that time, the industry’s decline was very much still unfolding, and there was still hope that articulating an effective feminist response could slow the hemorrhaging of unionized jobs and even bring unionization levels back up to their postwar levels. This article revisits the same event almost 40 years later and reassesses some of Lipsig-Mummé’s initial observations by placing them in the context of widespread industrial restructuring and deindustrialization across North America. See Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women.”

6. See Susana Miranda, “‘An Unlikely Collection of Union Militants’: Portuguese Immigrant Cleaning Women Become Political Subjects in Postwar Toronto,” in Marlene Epp and Franca Iacovetta, eds., Sisters or Strangers? Immigrant, Ethnic, and Racialized Women in Canadian History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 393–412.

7. See Wenona Giles, Portuguese Women in Toronto: Gender, Immigration, and Nationalism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002); Miranda, “Unlikely Collection.”

8. Christine Walley, Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 7.

9. There are, of course, notable exceptions. See Jefferson Cowie, Capital Moves: RCA’s Seventy-Year Quest for Cheap Labor (New York: New Press, 2001); Jackie Clarke, “Closing Moulinex: Thoughts on the Visibility and Invisibility of Industrial Labour in Contemporary France,” Modern and Contemporary France 19, 4 (2011): 443–458; Andy Clark, Fighting Deindustrialisation: Scottish Women’s Factory Occupations, 1981–1982 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022); Margaret Robertson and Andy Clark, “‘We Were the Ones Really Doing Something about It’: Gender and Mobilisation against Factory Closure,” Work, Employment and Society 33, 2 (2019): 336–344; Andy Clark, “‘And the Next Thing, the Chairs Barricaded the Door’: The Lee Jeans Factory Occupation, Trade Unionism and Gender in Scotland in the 1980s,” Scottish Labour History 48 (2013): 116–135; William Burns, “‘We Just Thought We Were Superhuman’: An Oral History of Noise and Piecework in Paisely’s Thread Mills,” Labour History, no. 119 (2020): 173–196; Rory Stride, “Women, Work and Deindustrialisation: The Case of James Templeton & Company, Glasgow, c.1960–1981,” Scottish Labour History 54 (2019): 154–180; Lauren Laframboise, “Gendered Labour, Immigration, and Deindustrialization in Montréal’s Garment Industry,” ma thesis, Concordia University, 2021.

10. See Margaret Little, Lynne Sorrel Marks, Marin Beck, Emma Paszat, and Liza Tom, “Family Matters: Immigrant Women’s Activism in Ontario and British Columbia, 1960s–1980s,” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture and Social Justice 41, 1 (2020): 105–123.

11. For a deindustrialization studies perspective, see, for example, Steven High, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022); Arthur McIvor, “Working-Class Studies, Oral History, and Industrial Illness,” in Michele Fazio, Christie Launius, and Tim Strangleman, eds., Routledge International Handbook of Working-Class Studies (New York: Routledge, 2020), 190–200. For a feminist labour history perspective, see Joan Sangster, Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Postwar Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 13–14.

12. Doreen Massey, “Places and Their Pasts,” History Workshop Journal 39, 1 (1995): 190.

13. Steven High, “Beyond Aesthetics: Visibility and Invisibility in the Aftermath of Deindustrialization,” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 84 (2013): 141.

14. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 2.

15. See Robert Storey, “‘By the Numbers’: Workers’ Compensation and the (Further) Conventionalization of Workplace Violence,” in Jeremy Milloy and Joan Sangster, eds., The Violence of Work: New Essays in Canadian and US Labour History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021), 160–183; Steven High, “The ‘Normalized Quiet of Unseen Power’: Recognizing the Structural Violence of Deindustrialization as Loss,” Urban History Review 48, 2 (2021): 97–116.

16. Joan Sangster, “Telling Our Stories: Feminist Debates and the Use of Oral History,” Women’s History Review 3, 1 (1994): 7.

17. Srigley, Zembrzycki, and Iacovetta, introduction to Beyond Women’s Words, 8.

18. As Steven High writes, listening across difference is “a unique learning landscape” that “represents a not-so-subtle shift from leaning about to learning with.” High, “Listening across Difference: Oral History as Learning Landscape,” Learning Landscapes 11, 2 (2018): 39–40.

19. See Sangster, “Telling Our Stories,” 11. See also Katherine Borland, “‘That’s Not What I Said’: Interpretive Conflict in Oral Narrative Research,” in Sherna Gluck and Daphne Patai, eds., Women’s Words: The Feminist Practice of Oral History (New York: Routledge, 1991), 63–75.

20. Joan Sangster, Demanding Equality: One Hundred Years of Canadian Feminism (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2021), 3–4.

21. See Leona Siaw, “Seam Stress: Garment Work and Gendered Labour Struggle in 1980s Montréal,” M.Sc. thesis, Concordia University, 2020.

22. “md” requested that her initials, rather than her full name, be used.

23. G. P. F. Steed, “Locational Factors and Dynamics of Montréal’s Large Garment Complex,” Tijdschrift voor Econ. en Soc. Geografie 67, 3 (1976): 151–168.

24. Robert McIntosh, “Sweated Labour: Female Needleworkers in Industrializing Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 32 (1993): 105.

25. Gail Cuthbert Brandt, Through the Mill: Girls and Women in the Québec Cotton Textile Industry, 1881–1951 (Montréal: Baraka Books, 2018), 15.

26. On Montréal and Canada, see McIntosh, “Sweated Labour.” On garment industries elsewhere, see Judith G. Coffin, The Politics of Women’s Work: The Paris Garment Trades, 1750–1915 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996).

27. Mercedes Steedman, Angels of the Workplace: Women and the Construction of Gender Relations in the Canadian Clothing Industry, 1890–1940 (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1997).

28. See Mercedes Steedman, “The Promise: Communist Organizing in the Needle Trades, the Dressmakers’ Campaign, 1928–1937,” Labour/Le Travail 34 (1994): 37–73.

29. Jacques Rouillard, “Genèse et mutation de la Loi sur les décrets de convention collective au Québec (1934–2010),” Labour/Le Travail 68 (Fall 2011): 12; Harold A. Logan, Trade Unions in Canada: Their Development and Functioning (Toronto: Macmillan, 1948), 210–211.

30. Mercedes Steedman, “Canada’s New Deal in the Needle Trades: Legislating Wages and Hours of Work in the 1930s,” Relations Industrielles 53, 3 (1998): 2.

31. Steedman, “Canada’s New Deal,” 2; Steedman, Angels of the Workplace, 7–8.

32. Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women,” 57.

33. Steedman, “Canada’s New Deal,” 2.

34. Lipsig-Mummé, “Organizing Women,” 52.

35. Rianne Mahon, The Politics of Industrial Restructuring: Canadian Textiles (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 46–51.

36. Mahon, Politics of Industrial Restructuring, 44.

37. Mahon, Politics of Industrial Restructuring, 97.

38. See Mahon, Politics of Industrial Restructuring, 32–38; Armine Yalnizyan, “From the dew Line: The Experience of Canadian Garment Workers,” in Linda Briskin and Patricia McDermott, eds., Women Challenging Unions: Feminism, Democracy, and Militancy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 286.

39. Mahon, Politics of Industrial Restructuring, 95.

40. Yalnizyan, “From the dew Line,” 288.

41. Tara Vinodrai, “A Tale of Three Cities: The Dynamics of Manufacturing in Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver, 1976–1997,” Micro-Economic Analysis Division, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, 2001, 12.

42. Vinodrai, “Tale of Three Cities,” 13.

43. See “Women and Children’s Clothing Industries,” Annual Census of Manufactures, Statistics Canada CS34-252-1995, Ottawa, 1995, xv.