Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Article

Deindustrialization, Gender, and Working-Class Militancy in Saint-Henri, Montréal

Abstract: Tracing the history of gendered working-class responses to deindustrialization in the Montréal neighbourhood of Saint-Henri reveals that many of the local political initiatives of the 1960s and 1970s were connected to longer-term working-class efforts to navigate shifting patterns of capital accumulation extending back to the 1940s. The gendered tradition of territory-based organizing in this community encouraged women workers’ shop-floor militancy and was foundational for new forms of local political advocacy around issues like health care and housing. In deindustrialization’s moment, the concerns of a precariously employed, feminized working-class population spurred a crossover of industrial struggle with survival-focused reproductive labour issues, centred around a grassroots organization called the popir (Projet d’organisation populaire, d’information, et de regroupement). This pattern of gendered working-class militancy and solidarity persisted throughout the 1980s and shaped resistance to Saint-Henri’s subsequent gentrification at the turn of the new millennium.

Keywords: deindustrialization, gender, housing, Saint-Henri, working class, women, gentrification

Résumé : Retracer l’histoire des ripostes de la classe ouvrière à la désindustrialisation dans le quartier montréalais de Saint-Henri dans une perspective genrée permet d’établir des liens entre les initiatives politiques locales des années 1960 et 1970 aux tentatives d’adaptation de la classe ouvrière au contexte changeant d’accumulation du capital qui remontent à la décennie 1940. La tradition genrée de l’organisation locale au sein de cette communauté a encouragé le militantisme des travailleuses sur le plancher des usines et est au fondement de nouvelles formes d’organisations locales de défense des droits autour d’enjeux comme l’accès aux soins de santé et au logement. Dans un moment de désindustrialisation, les préoccupations d’une population ouvrière précaire et majoritairement féminisée ont donné l’élan au croisement entre les luttes industrielles et les enjeux de survie liés au travail reproductif, concentré au sein d’une organisation de base nommé le popir (Projet d’organisation populaire, d’information et de regroupement). Ce schéma de militantisme et de solidarité mené par une classe ouvrière genrée a persisté jusque dans les années 1980 et a servi de modèle à la résistance contre l’embourgeoisement de Saint-Henri au tournant du millénaire.

Mots clefs : désindustrialisation, genre, logement, Saint-Henri, classe ouvrière, femmes, embourgeoisement

“I’ve always lived in Saint-Henri. I came into the world here, on Beaudoin Street … I knew Madeleine Parent. She was in the union. She was good. I liked her a lot.”

—Émilia Cartier (1972)

Like other major North American cities in the postwar period, Montréal was heavily impacted by deindustrialization.1 This was especially the case for its industrial inner-city Southwest neighbourhoods: in total, more than 10,000 manufacturing jobs disappeared from the sector between 1951 and 1973, and some 30,000 people left the area.2 In the Southwest Montréal neighbourhood of Saint-Henri, 85 different factories closed over this twenty-year period.3 One after another, major employers such as Dominion Textile (1967), Westeel-Rosco (1969), General Steel Wares (1970), and rca-Victor (1971) shut their doors or moved production elsewhere; those that remained, like the Johnson Wire Works and Imperial Tobacco, significantly reduced their personnel.4 In their place, there proliferated a short-lived generation of dangerous, non-unionized, secondary industries that employed young local women and migrant labourers.

Tracing the history of gendered working-class responses to deindustrialization in Saint- Henri, with a particular focus on a grassroots community organization called the popir (Projet d’organisation populaire, d’information, et de regroupement), reveals that many of the local initiatives of this period were connected to longer-term working-class efforts to navigate shifting patterns of capital accumulation extending back to the 1940s. The gendered tradition of territory-based organizing in this community encouraged women workers’ shop-floor militancy and was foundational for new forms of local political advocacy emerging in the 1960s around issues like health care and housing. In deindustrialization’s moment, the concerns of a precariously employed, feminized working-class population spurred a crossover of industrial struggle with survival-focused reproductive labour issues. This pattern of gendered working-class militancy and solidarity persisted and shaped resistance to Saint-Henri’s subsequent gentrification at the turn of the new millennium.

This article, then, briefly explores the local dynamics of class decomposition and recomposition occasioned by broader shifts in capitalist production in the postwar period, setting the stage for a more in-depth treatment of the new forms of community and shop-floor organization that emerged in Saint-Henri in the 1960s and 1970s. It closes with an analysis of the impact of this movement’s genealogy on local responses to post-shutdown gentrification in the turn to the new millennium. In doing so, it contributes both to the project of broadening the scope of the largely male-focused field of deindustrialization studies and to the work underway by a new generation of historians of Québec who are taking on the social developments of the post-’60s era (including within the feminist movement), inserting a healthy dose of working-class experience and struggle into a body of work that has focused largely on intellectual history and left political discourse.5

Capital and Gendered Class Restructuring

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the factories concentrated along Southwest Montréal’s Lachine Canal made up the beating heart of industrial capitalism in Canada. First begun in the 1680s under the auspices of the seignorial Sulpician order, the canal’s digging was taken up again in the 1820s and then expanded in the 1840s – propelled forward by British merchant capital and made possible through the bloody repression of Irish labourers.6 A series of unruly industrial suburbs in what became known as “Smokey Valley” grew along with capital’s rush to the banks of the narrow shipping artery, several of which were incorporated into the new town of Saint-Henri in 1875, annexed to Montréal in 1905.7

As geographer Robert Lewis has argued, the expansion of industry in the West End of Montréal in the second half of the 19th century and early decades of the 20th was part of a continual North American process of industrial suburbanization dating back to the 1700s. Companies were originally drawn to the Southwest because of haphazard and poorly planned tax breaks and concessions. In turn, production continued to be propelled outward in the postwar years by speculative construction cycles and real estate investment on the industrial fringe, exacerbated by a mode of production “that demonstrates persistent unevenness in rates of growth and capital accumulation among different industrial sectors and places.”8

These contradictions made themselves felt in the 1970 closing of the Lachine Canal. The canal was neither necessary after the 1959 opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway nor well suited to facilitate capital’s attempt to expand and diversify production in the face of a wartime glutting of the market.9 In 1973, a joint committee was formed to study the problem of industrial erosion, bringing together representatives from industry, labour and community groups, and the municipal and provincial governments. In a spring meeting of the project’s business caucus, one employer expressed doubt about the possibility of finding solutions, commenting that “it’s often financially advantageous for a company to move, because then it can obtain subsidies.”10 Dominion Textile, for example, sought to compensate for changing market conditions by moving into synthetic materials – refurbishing old plants where possible and building new facilities outside the city, with the help of over $800,000 in federal assistance. Its Montréal plants where modernization would be more costly, such as that in Saint-Henri, were simply closed.11 Similarly, rca moved its production to suburban Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, where it had the space to fully accommodate a move into aerospace technology. Stelco’s Saint-Henri facility moved to Contrecoeur, east of Montréal; Westeel-Rosco and General Steel Wares, to Baie d’Urfé, on the West Island; General Foods, to Lasalle; and the list goes on. In a city with still few public transit options, workers either followed their jobs or were left behind.12 In most cases these were intermediate steps to a broader global restructuring, bridged by the process of industrial suburbanization and facilitated by the onset of new free trade regimes.13

Deindustrialization was also a reaction to working-class organizing. Responding to a series of 1940s and 1950s strikes at the company’s Québec facilities, Dominion Textile ceo Ryland Daniels complained in 1966 that “Canada is pricing itself right out of both world and domestic markets because of demands of labor and spending of government … Gradually a change has evolved so that business (still pictured in striped trousers) is given the bulk of the responsibilities, whether real or imagined, while state, labor, and that amorphous body ‘society’ lay claims to the rights.”14 And Dominion Textile was not the only neighbourhood manufacturer encouraged to cut jobs or to relocate altogether by an upsurge of industrial working-class militancy, spurred on by wartime labour shortages and a new, more expansive federal system of industrial legality.15 Steelworkers at Stelco unionized in 1945 and fought two important strikes, first in 1946 to gain equal pay with their Ontario counterparts, and then again in 1962 around issues of job classification and salaries.16 At Imperial Tobacco, a strike led by Haudenosaunee women workers in 1942 led to recognition of the Tobacco Workers’ International Union and won employees a “48-hour week, paid vacations, maintenance of membership and a joint application to the Regional War Labour Board for a five-cent-an-hour increase.”17

While these struggles were part of a broader national upswing in industrial organizing, they were also place-based and gendered campaigns. As historian Denyse Baillargeon reminds us, “the unionization of women workers by leading figures such as Madeleine Parent and Léa Roback that began during the Second World War also helped to strengthen women’s activism,” pointing to women workers’ militancy in the hard-fought textile strikes in Valleyfield, Lachute, Louiseville, and Montréal.18 United Textile Workers of America organizer Parent, for example, painstakingly rallied the feminized workforce at Dominion Textile in the 1940s through a series of kitchen-table meetings at homes throughout Saint-Henri, with neighbours congregating around doorways and windows to hear what she had to say.19 And Roback, engaged in the same period in an organizing drive at rca, remembered in a 1978 interview that “If you work in a neighbourhood, you’re part of it. The workers live there, and not in Côte-des-Neiges.” When the textile strike kicked off, rca employees were there in support: “We didn’t have any money to give to our comrades,” Roback remarked, “but by our presence on the picket lines the workers of St-Henri wanted to assure them that they weren’t alone in being exploited in the neighbourhood.”20 Stelco workers collected funds for Dominion Textile strikers in 1946, and local unions became heavily involved in the struggle for better housing.21 Over the course of the decade, the working class in Saint-Henri slowly reached toward greater control over the productive and reproductive forces structuring the neighbourhood, moving gradually from its constitution by capitalism as a “mass of people [with] a common situation with common interests” to its own self-constitution, as a “class for itself” engaged in political struggle against its antagonists.22 Manufacturers had obvious incentive, then, to begin moving toward greener pastures in their “continual struggle to maintain the social conditions deemed necessary for profitability.”23

The impact of capital’s push to maintain profits in the deindustrializing economy was disproportionately borne by the neighbourhood’s women. As feminist labour historians have argued, the traditional focus on white male breadwinners in the supposed Fordist, postwar consensus years obscures as much as it reveals – not least the ways in which precarity and contingency were already creeping back into the labour market via the experience of the rapidly increasing number of women workers.24 By 1951, women made up 24.5 per cent of the total Québec workforce, second in Canada only to neighbouring Ontario. Seventeen per cent of those women workers were married, compared with only 7.5 per cent a decade earlier, indicating changing realities within household sexual divisions of labour.25 By 1961, women made up 39 per cent of the workforce in Saint-Henri; 39.4 per cent of these women workers, in turn, held industrial jobs (compared with 23 per cent in the city as a whole). And 17.3 per cent of women in the neighbourhood made under $1,000 per year, compared with 8.9 per cent of men.26

In shops like rca, for example, foremen took advantage of women’s reproductive roles to justify firings and layoffs.27 Despite this, women workers did not conceive of their work as “temporary,” as necessity prevailed even in the height of Fordism. One rca employee, when told she could take a well-earned rest when the “boys” came back from the war to take over her factory position, responded, “What are you trying to do, kid me? How can my André earn enough to keep me and the three children? Even if the 2 others were to go to work, they still wouldn’t earn enough, I want them to take up a trade and not have to go through what I have. They will be able to get jobs then, in Union Shops, and earn a decent wage, and then perhaps I will be able to rest, but until then, full speed ahead.”28

The labour struggles of the 1940s had been as much about pushing back against invasive scientific management techniques – “the damned timekeeper,” as Roback referred to the supervisor – as they had been about wages.29 But unionization did not bring about a softening of gendered power relations or a slowing of the pace for the increasingly feminized workforce. One assembly line worker at rca, interviewed in 1996, recalled of her first day in 1952 that “there were at least 150 of us girls on the line, and they put me at the very end … they just said, ‘Figure it out yourself,’ and that was it. I was new and very anxious and stressed. So the boss arrives, he says, ‘this one is too slow.’”30 Furthermore, in the heavily feminized textile industry, wage increases won during the war were offset by an intense, exhausting piecework regime.31 Denise Tanguay-Dufault, a single mother who supported a family of six, remembered being paid by the piece throughout her career at Dominion Textile: “Always by the piece! And they gave us … every week, they gave, they gave, they pulled out a sheet, and they gave the results. So y’know we always, always had to surpass ourselves to get a decent wage.”32 The breakneck speed required to maintain a basic salary affected workers’ health and undermined solidarity on the shop floor.33

The intensification of the exploitation of women was also facilitated by the patriarchal norms and values of male members of the working class, following deep-set patterns within the labour movement that saw the home as the rightful place of women workers.34 In the regular “Labour Echoes” column that appeared in local paper La Voix Populaire in the late 1950s and early 1960s, for instance, women workers were rendered almost entirely invisible – except when the labour columnist was relaying advice for how wives could support their husbands on strike.35 René Cartier, a member of the Groupement familial ouvrier (a local initiative of Jesuit worker-priest Jacques Couture), similarly waxed poetic about the respective roles of the working-class nuclear family: “But the most beautiful thing, it’s returning at night/to your family, to your home/you say: another day done!/you have to hear the cries of the children/when daddy comes/their faces in the window/and mommy and her hot dishes.”36

As deindustrialization worsened, so too did the situation of women workers. Considered temporary labour and forced to accept degrading work environments to support their families, they faced an uphill battle for better conditions.37 It was their community-based labour organizing, however, that would set the tone for the local movement in the years to come.

From Animation Sociale to the Struggle against Deindustrialization

Criss-crossed by rail lines and beset by major highway and urban renovation projects, delimited by the deindustrializing canal to the south and the wealthy anglophone city of Westmount to the north, working-class, francophone Saint-Henri in the 1960s and early 1970s was socially and geographically isolated. In 1966, 32.7 per cent of families in Saint-Henri and neighbouring Little Burgundy had at least five children.38 With a surplus of large, young families, and with almost three-quarters of household heads in the area earning less than $3,000 per year, 80 per cent of residents aged 15 to 24 dropped out of school before completing grade 9. Social problems were compounded by overcrowding and poor housing conditions.39 In Saint-Henri, 92 per cent of the population were tenants, crammed into a housing stock of which the vast majority was built before 1920.40 Infant mortality rates in 1969 were at 28.3 per cent per 1,000 inhabitants, compared with an average of 19.8 per cent for Montréal.41

This was also the decade of animation sociale, in which young professionals under the auspices of the lay Catholic Conseil des Oeuvres de Montréal (com) – inspired by a hodgepodge of influences including Saul Alinsky’s ubiquitous community development philosophy, Catholic social action, and the technocratic democracy of early Quiet Revolution state planning – came to the neighbourhood to organize participation citoyenne around concrete and limited local problems.42 These professionals generally conceived of themselves as political pioneers, arriving in a neighbourhood where, as former com organizer Michel Blondin recently recalled, “The citizens were disorganized and ignored.”43 Their work, as they saw it, was to interest citizens in their own circumstances, to help them analyze their conditions, and to engage in action to change them. Social animators therefore assumed the role of agents of “(a) reason, (b) socialization, and (c) information. Not everyone is cut out for this work!”44 Increasing numbers of Catholic priests and nuns, too, many of whom had been influenced by missionary experiences abroad, came to Saint-Henri seeking to enact the progressive dictates of Vatican II in Québec.45

Historian Will Langford has written what is probably the most in-depth exploration of Saint-Henri’s left politics of the 1960s, analyzing the activism of the young members of the federally funded Company of Young Canadians (cyc). These volunteers were deeply involved in social animation and the support of block committees created in the wake of expropriation and urban renewal in what would become the new neighbourhood of Little Burgundy, east of Atwater Boulevard; they moved radically to the left after deciding to operate exclusively in Saint-Henri, getting involved in the Comité ouvrier de Saint-Henri (cosh) and practising what Langford refers to as “animation révolutionnaire” – nothing less than the “politicization of the masses.”46

While the organization dissolved under the repression of the municipal Drapeau-Saulnier administration, as part of a general crackdown on cyc activities in Montréal in the lead-up to the October Crisis, Langford demonstrates that a second “stream” of cyc volunteers were involved in shop-floor organizing after the cosh experiment, although with an ideology more reminiscent of Italian autonomous Marxism than of the radical nationalism of the 1960s. cosh had made an aborted attempt to organize Eagle Toys-Coleco – the firm that had set up shop in the Dominion Textile building in September 1968 – describing the conditions faced by the 800-strong workforce (70 per cent of whom were women, the rest immigrant men) as a “concentration camp.”47 In 1971, Eagle Toys workers would be assisted by popir organizer Benoit Michaudville, who received funding from the Métallos (Steelworkers) with the goal of breaking the grip of the company union, the Fédération canadienne des associations indépendantes (fcai). The success of this effort inspired cyc volunteers to lend a hand to an organizing committee for the multiracial, largely female workforce in the Lumiray plant.48

What Langford describes as the “endemic conditions” of these factories, concentrated in secondary industries like plastics and electronics and reliant on the unskilled labour of young women, was in fact the penultimate stage of industrial capital’s dynamic, broader global restructuring in the second half of the century – a sort of final, hurried draining of the well of labour power before its uprooting from the North American urban milieu, pushing the general trend toward feminized precarity to new heights.49 These young workers were increasingly alienated from the labour movement and from one another. For a teenager like Carole Orphanos, who dropped out of school and got her first job at Coleco in 1974 assembling table hockey games, the casualness of the employment relationship did not, initially, seem to be a problem as long as other work was available: “It was incredible in the factories. I was really happy,” she remembered in 2018. “If you didn’t like where you were working, you just said, ‘see ya later!’ and you went to the place next door.”50 Dorisse LeBlanc, interviewed in 2020, similarly rattled off a long list of temporary jobs in the neighbourhood’s plants. She is skeptical of those out of work today: “I said: ‘Me, I’m not educated and I found work. How do you explain that?’ And today you need education; it’s not true. I’d go into a factory and get a job tomorrow, if I wanted.”51

This easy circulation from job to job, however, was designed to keep wages low and solidarity to a minimum. Even after the initial union battle at Eagle Toys was won in 1971, workers needed three months’ seniority before becoming part of the bargaining unit, and the company did all it could to prevent this from happening. Orphanos remembers, “Those guys, before you got your three months in, they laid you off. So you couldn’t get in the union. I went back later, and they took me on again, but for less than three months. I think I did that three times.”52 Organizing under these conditions was not easy.

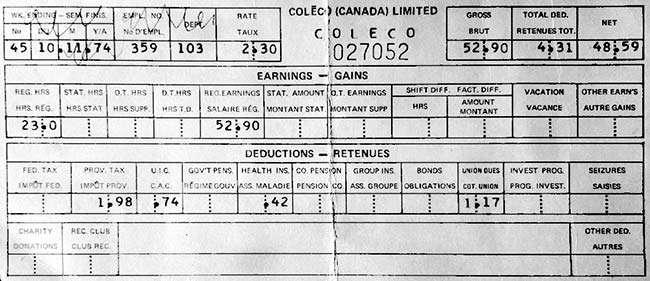

Carole Orphanos’ 1974 pay stub from Coleco, a toy company in Saint-Henri with notoriously poor working conditions.

From the personal collection of Carole Orphanos.

What success the labour movement had in these plants, however, was due to the cross-fertilization of a variety of forms of working-class struggle happening within the popir. The original impetus for the popir came from Blondin and the reformist approach of animation sociale. Winding up his time in Saint-Henri and seeking to give some institutional solidity to the various citizens’ committee initiatives in the Southwest, in 1969 Blondin worked out a deal with the Archbishopric of Montréal to fund the new organization for a period of two years.53 Initially, the organization had a hybrid “Comité directeur,” with three directors named by the Archbishopric, three from the Conseil de développement social du Montréal Métropolitain (CDS, the new name adopted by the com in 1969),54 and eight from the various citizens’ committees around the Southwest. Significantly, only four of the original fourteen directors were women.55 The popir employed several social animators, assisted in their duties by cyc volunteers. While the arrangement was not without its tensions, work began quickly in the form of “study groups” on different issues facing Southwest residents, taking on several main fronts of struggle: housing, consumption, health care, and labour.56

The young organization’s labour front was particularly effective. Two ateliers de travail – one for Saint-Henri and one for neighbouring Pointe-Saint-Charles, or “the Point” – quickly became important hubs of worker investigation, as men and women from the Southwest’s various factories (for example, Dominion Glass, CNR, and Belding Corticelli, in Pointe-Saint-Charles; Eagle Toys and Simmons Bed in Saint-Henri; and Crane, from across the canal in Côte-Saint-Paul)57 came together to analyze the conditions of their increasing exploitation. During a November 1970 meeting, participants detailed the pernicious cycle wherein increasing unemployment forced workers to accept worse conditions, making for frequent turnover when they were no longer able to tolerate the job. These “voluntary” departures kept companies from having to shell out unemployment benefits and created a permanent state of precarity in the workforce. Attendees also noted that men were increasingly being replaced by lower-paid women and that plants in the Southwest expected them to do more work in less time, with fewer employees. As such, workers had “no time to go to the toilet, no fun on the job.”58

The members of the ateliers de travail organized kitchen-table meetings with workers throughout the Southwest, leading up to an all-day event in December 1970 where one of the principal issues discussed was the problem of the employer-friendly fcai, particularly at the Clix Fastener zipper factory in Verdun. The fcai, recognized even by the provincial Labour Relations Board as working assiduously with employers to intimidate and silence authentic unionization efforts, had been a target of the cosh at Toilet Launderies and Eagle Toys on the north side of the canal. Following the December colloquium, Clix workers got organized and it became the first worksite to successfully get rid of the boss’s union for good.59

The atelier de travail in the Point transitioned into the Mouvement du Zip or the Mouvement des travailleurs du Sud-Ouest (mtso), which carried on mobilizing against the fcai in other plants in the area. The mtso also conducted a systematic investigation into deindustrialization and wage scales in the Southwest. Workers reported on conditions in their plants, and patterns began to emerge: Crane had lost most of its 700 employees; General Steel Wares, all 750; and rca, which had employed 1,500 workers in 1968, was going to employ only 150 to 200 in its new locale in the suburbs. Workers were left with minimum-wage jobs in small, non-unionized plants, or in laundry or food preparation.60

Another initiative with a full-time animator from the popir was the Secrétariat des Travailleurs du Sud-Ouest (stso). The stso concerned itself not only with shop-floor struggles but also with the increasing numbers of workers finding themselves on unemployment or welfare, creating a welfare rights group called the Organisation des Droits Sociaux. The Saint-Henri atelier continued to meet, bringing together the stso and a variety of autonomous initiatives that worked in collaboration with the popir. Southwest residents who were part of the “Gars de Lapalme” – delivery drivers engaged in what at that time was one of the most ferocious labour struggles in Québec history – also sent representatives to the meetings.61

Inside the popir, things were changing rapidly as the contradictions of social animation came to the fore. In March 1971, csd representative to the popir Pierre Pagé resigned from the former to become a full-time organizer at the latter, citing a desire to work more directly with those most affected by structural injustice.62 The csd pulled completely out of the popir shortly after, and the Archbishopric announced that it would not continue to fund the popir at the end of its original two-year mandate – part of a broader pushback of the Church against the more radical currents emerging out of Catholic social action.63 Looking toward the future, popir members no longer sought simply to incite citizen participation; instead, they stated their intention to “take power away from the minority that controls the Southwest and put it back in the hands of the majority.” The issue of deindustrialization was front and centre: “we have to find … ways that the unions can face up to the reality of factory closures in the Southwest; avenues through which the worker’s financial problems can be addressed that go beyond the household food budget.”64 Southwest militants were moving from a fight against an abstract notion of “poverty” to a struggle against exploitation and abandonment.

Significantly, the gendered composition of decision-makers within the popir had also changed dramatically, reflecting the changing composition of the industrial workforce: by the fall of 1971, almost half of its Comité directeur were women.65 Further, while the popir was originally conceived to cover all the neighbourhoods of the Southwest, and much of the original enthusiasm for the project had come from nearby Pointe-Saint-Charles, by the end of the year both the offices and the energy of the group had been firmly transplanted to Saint-Henri.66 It is in the light of these developments that the organization of Eagle Toys workers can be best understood. Langford’s account, detailed above, gives us the broad lines: the Métallos did indeed pay popir organizer Benoit Michaudville, who supported the young women workers driving the anti-fcai campaign; their experience of shop-floor activism led them, along with fellow workers from Lumiray and C.C.M. (in nearby Griffintown), to challenge the structures and procedures of central unionism.67 But Michaudville was not, before this initiative, a paid social animator at the popir; rather, he was a Saint-Henri militant whose trajectory closely mirrored the evolution of struggle in the Southwest. Originally a Jesuit theology student who had come to the area after being expelled from Brazil by the military dictatorship in 1969, Michaudville first lived in the Point. Working at Toilet Launderies brought him into contact with the cosh and workers’ struggles in Saint-Henri.68 He was an active participant in the atelier de travail and the mtso and soon became one of the volunteer directors of the popir.69 When a group of young women workers at Eagle Toys reached out to the Métallos, the union agreed to pay Michaudville the small sum of $1,500 (covering his living and organizing expenses from September 1971 to May 1972) to assist them.70

This new organizing initiative reflected discussions (in which Eagle Toys employees were regular participants) within Saint-Henri’s atelier de travail about working conditions and the fcai, as well as the increasing realization that the mtso strategy of trying to federate more politically advanced individuals from a variety of plants was not working. While staying rooted in the context of neighbourhood struggle, there was a need to organize workplaces, one at a time.71 As a member of the Comité directeur of the popir, where Eagle Toys workers often came as a group to help with different neighbourhood projects, Michaudville was able to rally broad support for the unionization effort.72 As he related to La Presse labour columnist Pierre Vennat, “without the activism of neighbourhood residents, none of this would have been possible.” With it, the campaign resulted in the unionization of 882 workers, spreading to shops like Lumiray, Canada Fibre Can, Thomas Bonnar, and Montreal-Phono. By comparison, Vennat pointed out, the Métallos had spent over $80,000 on “organizing” non-unionized workers in 1970 and had recruited only 800 across the whole of Québec.73 Madeleine Neveu, a young nun employed at Coleco, pointed out at the October 1972 congress of the Métallos that “everybody here is talking about the necessity of unionizing unorganized workers. We have proved that we can do this unionization work by making the neighbourhood our organizing base.”74

This convergence of territory-based struggle and class conflict was also rooted in a conscious engagement with some of the longer-term histories of working-class organizing in Saint-Henri touched on at the beginning of this article. In the spring of 1972 popir militants reached out to Léandre Bergeron, the founder of publisher Éditions Québécoises, who agreed to work with them to write a history of Saint-Henri. The finished product, Les gens du Québec (1): Saint-Henri, was released in November. While Michaudville headed up the initiative, twenty neighbourhood residents contributed to the final project. It is a remarkable document, at once an analysis of deindustrialization, a guide to the multiplicity of local political initiatives of the period, a deeply researched history of neighbourhood labour struggles, and a compilation of oral histories of Saint-Henri residents. The authors situated the legitimacy of their neighbourhood organizing in the longer local lineage of labour struggles, foregrounding experiences like that of Émilia Cartier, featured in the epigraph to this article, that testified to long-term rootedness in working-class sensibilities and campaigns.75 In contrast to the attitude of the social animators who arrived in the Southwest in the early 1960s, the authors of the book intended to demonstrate that “throughout the history of Saint-Henri, there have always been those who resisted,” according to Michaudville.76 These labour militants, organizing a base of impoverished women workers, were laying claim to the gendered neighbourhood class solidarity that had typified the shop-floor organizing of the 1940s and early 1950s.

As Langford points out, given the composition of working-class forces in the neighbourhood, the surge of this sort of militant labour activity in the first few years of the 1970s had a strong feminist tendency, both in the nature of the demands made upon bosses – equal pay for equal work, maternity leave – and in its critical relationship to the authoritarian and patriarchal structures of central unionism. Saint-Henri militants instead insisted on the importance of worker self-activity. While Langford rightfully points here to the influence of New Left autonomist thinking on the cyc volunteers who accompanied these workers in their organizing, we can just as easily look to the local turn from a vague antipoverty discourse to the sharper, class-based analysis occurring in the ateliers de travail, the stso, and the mtso, rooted in the local material conditions in which workers found themselves. If there is a resemblance to the political approach taken in other contexts, it is more a result of shared challenges than shared texts: social democratic unions wedded through bureaucracy to the capitalist state, for example, or the intensification of patterns of exploitation in a context of increasing deindustrialization.77

At any rate, while the Métallos were making headlines for their support for Québec independence, the Southwest workers criticized their union and its leader, Jean Gérin-Lajoie, for supporting the bourgeois Parti Québécois, for anti-democratic functioning, and perhaps above all for abandoning workers in the small and medium-sized industries that now dominated deindustrializing neighbourhoods like Saint-Henri. Central unions, they advanced, were only interested in increasing their coffers.78 These workers argued instead, Langford writes, for the necessity of a “politicized labour movement premised on class conflict and the assertion of worker control over production, capital, and employment.”79 Furthermore, in the convergence of shop-floor organizing with issues like food prices and health care, this organizing moment represented a potentially fruitful new shift within movement politics toward the integration of unwaged, reproductive labour into the organized class struggle.

Feminist Organizing and the Rise of Social Economy

The vibrancy of the early 1970s had a lot to do with the space for organizational experimentation afforded by the multiple sources of secular and ecclesiastical funding. As this support dried up, the popir gradually shifted away from shop-floor organizing.80 But the class politics of the earlier part of the decade did not simply disappear from the neighbourhood nexus. A working document defining the values of the popir in December 1976, for example, stated that the organization’s long-term goals were “socialism, communism, etc.” and that it positioned itself against “the exploitation of man [sic].”81

The reproductive aspects of class struggle became more prominent, albeit framed in the language of social rights. A principal form this took in the neighbourhood was the move toward housing struggles, first in the form of a short-lived tenants’ association, part of the Association des locataires du Montréal métropolitain, and then through active committees of the popir.82 By the early 1980s, popir militants organized themselves into two groups: one to defend tenants renting from private landlords, and one defending the rights of renters living in the new Habitations à loyer modique (hlm), subsidized public housing funded by federal and provincial housing authorities and managed by Montréal’s Office municipal d’habitation (omhm).83 The popir also helped tenants form four different housing co-operatives between 1977 and 1980. This work was accomplished in collaboration with the Services d’aménagement populaire (sap), part of a new wave of Groupes de ressources techniques funded by the provincial government and made up of progressive architects and community organizers.84 Founding co-ops required intense local participation: tenants studied different forms of co-property and government programs and conducted surveys of buildings that could potentially be renovated and converted to social housing.85

The popir also formalized the latent feminist tendencies of the 1970s neighbourhood movement. Reflecting the disproportionately gendered impact of deindustrialization, by the end of the 1980s almost 90 per cent of the people seeking assistance from the organization were women, dealing with poverty, isolation, and the stresses of single parenthood. Across Canada, industries with heavily feminized workforces such as textiles and electronics were hit hard by new free trade regimes. This was especially the case for Montréal. With a high concentration of its production in these sectors, the city saw its share of national industrial output drop from 17 per cent in 1976 to only 12.5 per cent in 1997.86 Consequently, women in the Southwest had an average income barely half that of men in the 1980s. In 1986, 54.5 per cent of families on social assistance were women-headed households, and 87 per cent had only one parent.87 The women coming to the popir were generally between 30 and 45, had little education or confidence, and needed to share their stories and be listened to. Attempts to meet the needs of this population resulted in several new projects, including the founding of an affordable daycare, the Garderie Paillason, and the creation of the Maison du Réconfort, an emergency shelter for women and their children.88 The increasing predominance of women in the organization, according to one 1981 report, reflected the household division of labour: “In general, when problems with housing, food, or money arise in a family, it’s the woman who comes to ask for help.”89 To facilitate the participation of these women in discussion sessions, the popir also instituted a daycare within its walls, Les P’tits popirs.90

While there was a certain focus on “leisure” activities like writing and self-expression workshops, other sessions offered in these years – self-defence and sexual health and boundaries, for example, or a “toast and coffee” breakfast to discuss the political and economic dynamics of women’s unpaid work in the home – point to Saint-Henri’s enmeshment in the collectively oriented Québec feminist movement of the 1970s and 1980s.91 There was always a class element underlying this activism, and these programs fostered political education and solidarity among the working-class women of the neighbourhood. Work, unemployment, and housing continued to be pressing issues.92 Finally, as the group faced pressure from funders to concentrate on one struggle, some activists within the organization argued that the popir was at its most dynamic when focused on the pressing housing issues of Saint-Henri. Ultimately, the membership agreed: after a series of extensive consultations, in 1988 the popir officially became the popir-Comité Logement (Housing Committee), assuming responsibility for tenants in Saint-Henri, Little Burgundy, and, on the south side of the canal, Côte-Saint-Paul and Ville-Émard.93

In parallel to these developments, the 1980s also saw an increasing turn in the Southwest to a new “social economy” approach to community organizing, that is, working in collaboration with private-sector partners to try to create employment and housing opportunities. This tendency was particularly strong across the canal in Pointe-Saint-Charles. Compared with the longer, drawn-out process in Saint-Henri, deindustrialization in the Point had been swift and brutal. By the end of the 1970s, observed sociologist Jean-Marc Garneau, “no hope of reconstruction was on the horizon. The grand economic actors, the representatives of industry and government were silent and helpless in the face of the catastrophe.”94 Activists tried to salvage what they could, adopting a community economic development model inspired by social animation and contemporary American attempts to stimulate bottom-up, neighbourhood-driven capitalist entrepreneurship.95 As time went on, the proponents of this strategy even started to develop a certain level of condescension vis-à-vis the movements from which they came; the president of the social economy group Programme Économique de Pointe Saint-Charles (pep), for example, argued in 1989 that unlike other groups, “we do what’s necessary to make our projects work, instead of ‘dying pure.’”96

The new popir-Comité Logement was vehemently opposed to this approach, and its spokesperson Kathy Lepage denounced the softer strategy in no uncertain terms:

For some time, talking about mobilization in the popular movement has been to go against the current. Many groups … push and promote a new strategy of community development: partnership or even social consensus. In the Southwest of Montreal, this trend is very strong and recognized by different groups without even a minimal questioning within the popular movement about its effectiveness and the price we pay when we function by consensus. The gains are far from obvious when we sit down with the directors of the Caisse Populaire [credit union] or businesses and other actors advocating interests different than ours. We have to seriously question ourselves in the face of this new trend in economic and social development in a context in which the state is disengaging from social policies.97

While local credit union directors and businesses might geographically be part of the neighbourhood structure, in the popir’s analysis there were still clear class lines that needed to be drawn. The adoption of this position upon the group’s emergence in the world of housing struggles is evidence not only of the organization’s recent roots in the shop-floor efforts of the 1970s but also of the impacts of the comparatively longer, drawn-out history of deindustrialization in Saint-Henri. Feminist organizing of the 1980s should be seen not as a rejection of the class-based approach of earlier years but rather as an extension of this militant tradition through a focus on the reproductive elements of the struggle.

These two visions – social economy versus more militant, class-based struggle – were to clash repeatedly throughout the 1980s and ’90s, as deindustrialization advanced throughout the Southwest and real estate capital gradually began to fill the void left by its industrial counterpart. A significant point of contention was the conversion of the old copak packaging plant, purchased in 1988 by McGill University for its new student residence. The popir and welfare rights group odas (Organisation d’aide aux sans-emplois) opposed the project, decrying not only the loss of industrial infrastructure but also the creeping forces of gentrification already at work in the neighbourhood. Those community groups that had bought into the social economy approach, led by the pep, negotiated a settlement wherein McGill agreed to loan $500,000 to the Fonds d’investissement social en habitation, a short-lived municipal creation discontinued in 1993.98 popir spokesperson Jean-Pierre Wilsey warned that this collaborationist model signalled that Saint-Henri was a “neighbourhood for sale” and would drive up land prices and make social development dependent on private capital.99

His words proved prescient, unfortunately, as the state-led transformation of the Lachine Canal proved to be a particular incentive for capitalist developers. A joint provincial-federal commission held a series of consultations throughout the early 1990s on the necessity of cleaning up the canal, ultimately ruling in 1996 that a decontamination was not necessary before the water could be reopened to pleasure craft navigation100 From 1997 to 2002, the municipal and federal governments invested more than 100 million dollars in the refurbishing of the canal.101 Major real estate projects quickly followed, as investment funds increasingly financed “new-build gentrification” in the sector.102 La Presse journalist Danielle Turgeon reported in 2002, “Five years ago, no one boasted of living in Point St. Charles, Little Burgundy, or Saint-Henri … Now not only do buyers rush to the doors of the new projects near the Atwater Market and the Lachine Canal, but they pay high prices to live there.”103 From 1997 to 2007, almost 600 million dollars was invested in real estate in the Southwest, much of it on the Saint-Henri stretch of the canal.104 The former Dominion Textile building became the upscale Château Saint-Ambroise in 1999, featuring a much-vaunted complex of commercial lofts and restaurants.105 In 2002, the former site of Stelco’s Saint-Henri plant was converted by major developer Alta Socam into the luxury condo development Quai des Éclusiers.106 The rapid real estate boom in the Southwest invoked a 7.3 per cent municipal tax increase in 2010, the highest anywhere in the city.107 Driven upward by the massive condo developments along the canal, property values in the neighbourhood increased by 177 per cent between 1996 and 2006, with a concomitant 29.6 per cent increase in rental prices.108

As the state and capital poured resources into the repurposing of the Lachine Canal, the pep’s successor group, the Regroupement pour le relancement économique du Sud-Ouest (reso), sought to harness the process for the benefit of local actors, arguing throughout a series of public consultations for the importance of a “mixité” of economic functions along the waterway, including environmental tourism, “new economy” industrial development, and residential construction.109 In 2000 the group organized a massive public forum on the future of the canal, bringing together community groups with public institutions, corporations, and the financial sector.110

Louis Gaudreau, an organizer at the popir between 2000 and 2007, vehemently called out the limits of the reso’s vision of local participation. The supposedly participatory process, Gaudreau said, was technocratic, anti-democratic, and profoundly useless – almost the entirety of the Lachine Canal had been developed into condominiums anyway. The crucial flaw, he argued, was that the proponents of the accommodationist, social economy approach refused to recognize that simple participation could not begin to affect change in a profoundly inegalitarian urban system rooted in private property.111 “We don’t trust wishful thinking and promises,” said Wilsey.112 “On ne veut pas de condos,” chanted Saint-Henri tenants in a Fall 1997 action, “ça nous prend des boulots!” (We don’t want condos, we need jobs!). Demonstrators marched to the banks of the canal with a symbolic condo project made from plywood and proceeded to light it on fire.113 The roots of neighbourhood organizing in militant shop-floor struggles were still on display.

Conclusion

The post-industrial gentrification of Saint-Henri has reached new heights in recent years, with speculation-driven rent hikes and evictions driving low-income people out of the neighbourhood in droves.114 Neither collaboration nor a more militant approach has of yet proved up to the task of blocking real estate capital to any significant extent. Yet local resistance has remained steadfast, rooted in a popir membership still mostly made up of working-class women tenants – a population disproportionately affected by the currents of displacement sweeping the neighbourhood.115 This political tradition, as I have tried to show here, is connected to the brief crossover of neighbourhood-based shop-floor organizing in the feminized, light-industry plants of the deindustrializing 1970s with mobilization around issues like housing, food access, and health care, a convergence that shaped the feminist direction of the 1980s and the refusal to countenance collaborationist social economy approaches in the new millennium. The new energy of the 1970s moment, further, was partially due to a conscious defence and adoption of the longer legacy of working-class organizing in Saint-Henri going back to the early 1940s, in addition to being shaped by the gradual de- and re-composition of local class structures during the long process of postwar deindustrialization.

The salience of gender in the case of Saint-Henri makes obvious what tends to be obscured in deindustrialization studies, a field that often focuses exclusively on male-dominated, heavy-industry sectors like steel and mining.116 Examining working-class experiences of closures in urban industrial neighbourhood contexts through the prism of reproductive struggles around issues like housing sharpens our understanding of the ways that, as historian Lauren Laframboise argues, “gender not only shapes women’s experiences of waged industrial work, but also the interaction between deindustrialization, the gendered structures of that industrial work, and their unwaged work within the home.”117 While working-class women in Saint-Henri were certainly the ones who came looking for help from community organizations when food was scarce and money was tight, this was compounded by the fact that they increasingly became their households’ sole breadwinners as well. Organizing from these two sites of exploitation made for a militant outlook.

What the future holds for Saint-Henri’s working-class militant tradition is of course far from certain: issues like the overprofessionalization of community-based struggles, movement dependence on a crumbling nationalist welfare state, and an increasingly alarming housing crisis all are significant challenges to continued grassroots organizing. But as popir militants wrote in 2011, “St. Henri’s industrial past has left a heritage which still defines the neighbourhood today. The entire sector has a long tradition of social struggle, popular organization, mutual aid and solidarity. This is the St. Henri that we love and it is with it, and not against it, that we want to build.”118

Thanks very much to the three anonymous reviewers, to the editors of Labour/Le Travail, and to Steven High and Lachlan MacKinnon for helpful suggestions. The doctoral dissertation from which this work emerged was funded by fellowships from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et Culture and the Deindustrialization and the Politics of Our Time sshrc Partnership grant and was carried out on unceded Kanien’kehà:ka territory, in Tio’tia:ke (Montréal).

1. This article draws liberally on chapters 2 and 3 of my doctoral dissertation. See Fred Burrill, “History, Memory, and Struggle in Saint-Henri, Montreal,” PhD diss., Concordia University, 2021.

2. Comité pour la relance de l’économie et de l’emploi du Sud-Ouest de Montréal (creesom), Sud-Ouest: Diagnostic (Montréal: creesom, 1988), 24.

3. Claude Larivière, St-Henri: L’univers des travailleurs, Cahier 3 (Montréal: Éditions Albert St-Martin, 1974), 102.

4. Larivière, St-Henri, 87–106; Benoit Michaudville, “Histoire,” in Michaudville, ed., Les gens du Québec (1): St-Henri, 6-11 (Montréal: Éditions Québécoises, 1972); Rapport Final du Comité de reclassement des employés de rca Limitée, Groupe représenté par le Syndicat International des Travailleurs de l’Electricité, de Radio, et de Machinerie, P764, S4, SS3, SSS1, 1999-04-014/86, Directeur du Service de reclassement de la main d’oeuvre, Fonds Pierre-F. Côté, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (banq).

5. See, for example, Sean Mills, The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010); Flavie Trudel, “L’engagement des femmes en politique au Québec: Histoire de la Fédération des Femmes du Québec de 1966 à nos jours,” PhD diss., Université du Québec à Montréal, 2009; Camille Robert, Toutes les femmes sont d’abord ménagères (Montréal: Éditions Somme toute, 2017).

6. See H. C. Pentland, “The Lachine Strike of 1843,” Canadian Historical Review 29, 3 (September 1948): 255–277; Dan Horner, “Solemn Processions and Terrifying Violence: Spectacle, Authority, and Citizenship during the Lachine Canal Strike of 1843,” Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire urbaine 38, 2 (Spring 2010): 36–47.

7. On 19th-century working-class life in Saint-Henri, see Kathleen Lord, “Permeable Boundaries: Negotiation, Resistance, and Transgression of Street Space in Saint-Henri, Quebec, 1875–1905,” Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire urbaine 33, 2 (2005): 17–29; Gilles Lauzon, “Cohabitation et déménagements en milieu ouvrier montréalais: Essai de réinterprétation à partir du cas du village Saint-Augustin (1871–1881),” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 46, 1 (1992): 115–142. See also Yvon Desloges and Alain Gelly, Le canal de Lachine: Du tumulte des flots à l’essor industriel et urbain, 1860–1950 (Québec: Les éditions du Septentrion, 2002).

8. Richard Walker and Robert Lewis, “Beyond the Crabgrass Frontier: Industry and the Spread of North American Cities, 1850–1950,” in Robert Lewis, ed., Manufacturing Suburbs: Building Work and Home on the Metropolitan Fringe (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 27. On Montréal’s West End, see Robert Lewis, Manufacturing Montreal: The Making of an Industrial Landscape, 1850–1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 221–253.

9. creesom, Sud-Ouest: Diagnostic, 185–186; Larivière, St-Henri, 91–92.

10. Résumé de la rencontre avec les employeurs du Sud-Ouest tenue le 10 mai 1973, aux locaux de l’Impérial Tobacco Ltée., 3810 rue St-Antoine, à 3.30 heures p.m., 100p-630: 03/18, Front populaire 1973, Fonds d’archives de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec, Archives uqam. My translation.

11. Barbara J. Austin, “Life Cycles and Strategy of a Canadian Company: Dominion Textile, 1873–1983,” PhD diss., Concordia University, 1985, 628; Larivière, St-Henri, 97.

12. Larivière, St-Henri, 89–90, 98.

13. See, for example, Rianne Mahon, The Politics of Industrial Restructuring: Canadian Textiles (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984). Westeel Rosco is now owned by multinational agribusiness firm AGI, with production sites around the globe; Stelco was purchased by US Steel in 2007. Through a series of mergers and buyouts, different parts of what was General Steel Wares are now controlled by multinational giants General Electric, Mabe, and A. O. Smith, with facilities in Mexico, China, and India. General Foods became part of the global empire of the Kraft Heinz Company.

14. Cited in Austin, “Life Cycles,” 645. See also Denyse Baillargeon, “La grève de Lachute (1947),” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 37, 2 (September 1983): 271–289; Baillargeon, “Les grèves du textile au Québec: 1946, 1947, et 1952,” in Andrée Lévesque, ed., Madeleine Parent: Militante (Montréal: Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 2003), 45–59; Andrée Lévesque, “A Life of Struggles,” Labour/Le Travail 70 (Fall 2012): 189–192.

15. For general context, see Terry Copp, “The Rise of Industrial Unions in Montreal, 1935–1945,” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations 37, 4 (1982): 843–875.

16. Michaudville, “Histoire,” 11; Larivière, St-Henri, 95–96.

17. Copp, “Rise of Industrial Unions,” 868; Jeanne Maranda, “La syndicalisation féminine au Québec,” Canadian Woman Studies 25, 3 (2006): 47–49.

18. Denyse Baillargeon, A Brief History of Women in Quebec (Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2012), 140.

19. Benoit Michaudville, “Pour la Dominion Textile la fin justifie les moyens,” in Michaudville, ed., Les gens du Québec (1), 51. On histories of women workers’ militancy in Québec’s textile industry, see Gail Cuthbert Brandt, Through the Mill: Girls and Women in the Quebec Cotton Textile Industry, 1881–1951 (Montréal: Baraka Books, 2018); Baillargeon, “La grève de Lachute”; Baillargeon, “Les grèves du textile au Québec”; Lévesque, “Life of Struggles.”

20. Léa Roback, cited in Lucie Leboeuf, “Léa Roback, ou Comment l’organisation syndicale est indissociable de la vie de quartier,” Vie ouvrière 28, 128 (1978): 470. My translation.

21. Théodore Garrett, quoted in Michaudville, ed., Les Gens du Québec (1), 32; Nicole Lacelle, Entretiens avec Madeleine Parent et Léa Roback (Montréal: Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 2005), 136; Leboeuf, “Léa Roback,” 470.

22. Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1910), 189. On the rich historical tradition inspired by this formulation, see Harvey J. Kaye, The British Marxist Historians: An Introductory Analysis (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995), 221–249.

23. Jefferson Cowie, Capital Moves: rca’s Seventy-Year Quest for Cheap Labour (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 2.

24. Joan Sangster, Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Postwar Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 5–7.

25. Cuthbert Brandt, Through the Mill, 228–229.

26. Louise Chabot-Robitaille, De l’eau chaude, de l’espace et un peu de justice: Des citoyens de quartiers ouvriers analysent leur situation (Montréal: Conseil de développement social du Montréal métropolitation, 1970), 79.

27. Leboeuf, “Léa Roback,” 468–469.

28. Causes – Labour, Radio Addresses, Women Workers – 1945, 00026, Fonds Léa Roback, Jewish Public Library Archives, Montréal.

29. Lacelle, Entretiens, 148. My translation. On working-class resistance to scientific management, see David Montgomery, Workers’ Control in America: Studies in the History of Work, Technology, and Labor Struggles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

30. Madame Allard, interview, 1996. My translation. This interview was conducted by volunteers at the Musée des Ondes Emile-Berliner, a clip of which was graciously provided to me by Dr. Anja Borck, the museum’s director.

31. Cuthbert Brandt, Through the Mill, 155, 279.

32. Denise Tanguay-Dufault, interview by Paul-Émile Cadorette and Katy Tari, 1 December 2010, cohds-12-14 Parcs Canada (Mon Canal) Collection. My translation.

33. Paule Beaugrand-Champagne, “Les ouvrières du textile: C’est inhumain,” Le Travail 42, 5 (July 1966): 10–11.

34. See, for example, Éric Leroux, “Un moindre mal pour les travailleuses? La Commission du salaire minimum des femmes du Québec, 1925–1937,” Labour/Le Travail 51 (Spring 2003): 81–114.

35. Maurice Hébert, “Échos syndicaux: Le role des femmes dans une grève,” La Voix Populaire, 12 October 1960.

36. René Cartier, “Mon Quartier,” Opinion ouvrière: Le Journal des Travailleurs Pour les Travailleurs 1, 2 (January 1968): 7.

37. Le centre des femmes, “Femmes en lutte à Coleco,” Québécoises Deboutte! 1, 6 (June 1973): 50–51.

38. Françoise Marceau, “Le ‘Sud-Ouest’ C’est Quoi?,” May 1970, 5, P611.003.01, Saint-Columba House Fonds (Saint-Columba), banq.

39. Benoit Michaudville and Pierre Durocher, “L’Avenir du Comité ouvrier de Saint-Henri,” Relations 345 (January 1970): 9.

40. Marceau, “Le ‘Sud-Ouest’ C’est Quoi?,” 10.

41. Larivière, St-Henri, 104.

42. See Vincent Garneau, “Le Conseil des oeuvres de Montréal: animation sociale démocratie participative,” ma thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2011, 37–47; Amélie Bourbeau, Techniciens de l’organisation sociale: La réorganisation de l’assistance catholique privée à Montréal (1930–1974) (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 158–178. On the interesting marriage of technocratic state power and social animation’s democratic impulse, see Tina Loo, Moved by the State: Forced Relocation and Making a Good Life in Postwar Canada (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2019), 91–120.

43. Michel Blondin, “Qu’était le quartier St-Henri avant le popir?,” popir-Comité Logement, 1969–2019: 50 ans de lutte (December 2019): 3. My translation. See also Michel Blondin, Yvan Comeau, and Ysabel Provencher, Innover pour mobiliser: L’actualité de l’expérience de Michel Blondin (Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2012), 33–69.

44. Compagnie des Jeunes Canadiens, “La cjc et la participation des citoyens dans la rénovation urbaine – une étude de cas,” August 1971, 28, 165mi02.2.10, cjc (Compagnie des jeunes canadiens), Fonds du popir. My translation. See also Michel Blondin, “L’animation sociale en milieu urbain: une solution,” Recherches sociographiques 6, 3 (1965): 283–304.

45. See Catherine Foisy, Au risque de la conversion: L’expérience québécoise de la mission au xxe siècle (1945–1980) (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017); Fred Burrill and Catherine LeGrand, “Progressive Catholicism at Home and Abroad: The ‘Double Solidarité’ of Quebec Missionaries in Honduras, 1955–1975,” in Karen Dubinsky, Adele Perry, and Henry Yu, eds., Within and Without the Nation: Canadian History as Transnational History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 311–340; Oscar Cole Arnal, “The Presence of Priests and Religious among the Workers of Post Quiet-Revolution Montreal,” [Canadian Society of Church History] Historical Papers (1995): 149–160; Martin Croteau, “L’implication sociale et politique de Jacques Couture à Montréal de 1963 à 1976,” ma thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2008.

46. Will Langford, The Global Politics of Poverty in Canada: Development Programs and Democracy, 1964–1979 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020), 133.

47. Eagle Toys, a Montréal company that originally had its factory in the north of the city, moved to Saint-Henri in 1968. It was purchased by Coleco, itself a conglomerate of several smaller New England manufacturers, in 1972. Daniel Guilbert, Saint-Henri Industriel: Anciennes manufactures et fantômes d’usines (unpublished manuscript, in possession of the author). I refer to this plant as Eagle Toys pre-1972 and Coleco thereafter. Pouvoir ouvrier, Spécial Eagle Toy, 1969, 2, 21p-900:02/30, Comité Ouvrier de Saint-Henri, 1969–1970, Collection de publications de groupes de gauche et de groupes populaires, Archives uqam. On the composition of the workforce, see Le centre des femmes, “Femmes en lutte à Coleco,” 42.

48. Langford, Global Politics of Poverty, 140–151.

49. Langford, Global Politics of Poverty, 126.

50. Carole Orphanos, interview by the author, 29 May 2018. My translation.

51. Dorisse LeBlanc, interview by the author, 16 January 2020.

52. Orphanos, interview. My translation.

53. Blondin, Comeau, and Provencher, Innover pour mobiliser, 67–68.

54. Garneau, “Le Conseil des oeuvres de Montréal,” 52.

55. Liste des Membres du Comité-Directeur du Projet popir, 1970, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1970), Fonds du popir.

56. Françoise David, “Le popir, 1970–1972,” in Frédéric Lesemann and Michel Thiénot, eds., Animations sociales au Québec, rapport de recherche (Montréal: École de service sociale, Université de Montréal, 1972), 330, in 165mi01.2.2, Historique, Fonds du popir.

57. Rapport de l’Atelier Travail, 26 October 1970, 165mi04.5.1, Atelier-travail (Activités se rapportent au travail), Fonds du popir.

58. Rapport de l’atelier “Travail,” 16 November 1970, 165mi04.5.1, Atelier-travail (Activités se rapportent au travail), Fonds du popir. My translation.

59. See 165mi04.5.2, Comité ouvrier de St-Henri, Fonds du popir; Pouvoir ouvrier, Spécial Eagle Toys, 1969; David, “Le popir,” 333; Extraits du Dossier fcai, publié par le Journal du Taxi, 1 December 1969, 165mi04.5.1, Atelier-travail (Activités se rapportent au travail), Fonds du popir.

60. Mouvement des travailleurs du Sud-Ouest, 5 April 1971, 165mi01.3.6.5, Projet Mouvement des travailleurs du Sud-Ouest, Fonds du popir; Projet popir, Rapport-Progrès du 1 janvier au 30 juin 1971, 3–4, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1971), Fonds du popir.

61. See Pierre Vadeboncoeur, 366 jours, et tant qu’il en faudra: Vive les gars de Lapalme (Montréal: Beauchemin, 1971).

62. Pierre Pagé to Yvon Belley, 16 March 1971, 165I02.2.6, Conseil de Développement Social, Fonds du popir.

63. David, “Le popir,” 338, 342. See Garneau, “Le Conseil des oeuvres de Montréal,” 57–68. See also Manon Cousin’s documentary on the politicization and pushback against the Fils de la Charité, worker-priests involved in militant shopfloor and community struggles in Pointe Saint-Charles and Saint-Henri: Les Fils (Montréal: K-Films Amérique, 2021), https://vimeo.com/ondemand/lesfils.

64. Projet popir – Centre d’Action St-Henri, 2, 5, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1971), Fonds du popir. My translation.

65. Procès-verbal de la rencontre du Comité directeur du popir tenue au 3904 ouest, Notre-Dame, 26 October 1971, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1971), Fonds du popir.

66. Projet popir, Rapport-Progrès du 1 juillet au 31 décembre 1971, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1971), Fonds du popir. On the Pointe-Saint-Charles roots of the popir, see Anna Kruzynski, “Du Silence à l’Affirmation: Women Making History in Point St. Charles,” PhD diss., McGill University, 2004, 202–204.

67. Langford, Global Politics of Poverty, 140–148.

68. “Aujourd’hui, Place Ville-Marie: Jeûne symbolique contre les tortures au Brésil,” Le Devoir, 1 April 1970; Michaudville and Durocher, “L’Avenir du Comité Ouvrier,” 8–11.

69. Rencontre stso – adds et popir 3 September 1971; Mouvement des travailleurs du Sud-Ouest 28 April 1971, 165mi01.3.6.5, Projet Mouvement des travailleurs du Sud-Ouest, Fonds du popir.

70. Le centre des femmes, “Femmes en lutte à Coleco,” 44; Pierre Vennat, “Le mouvement syndical ne fait à peu près rien pour organiser les non-syndiqués,” La Presse, 27 October 1972.

71. David, “Le popir,” 333, 335–336, 340; Rapport de l’Atelier-Travail, 26 October 1970/2 November 1970, 165mi04.5.1, Atelier-travail (Activités se rapportent au travail), Fonds du popir; “Journée d’étude du personnel du popir vendredi, 28 janvier ’72, au 675 Filaitrault; Rapport de la réunion de l’Exécutif du popir tenue le 7 février 1972, au 3904 Notre-Dame,” 165mi01.3.3, Conseil d’administration (1972), Fonds du popir.

72. Projet-popir, Rapport Progrès du 1 juillet au 31 décembre, 1971, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1971), Fonds du popir.

73. Vennat, “Le mouvement syndical”; Militantes de Lumiray, “Lumiray: Bilan d’une lutte,” Québécoises Déboutte! 1, 5 (April 1973): 18. My translation.

74. Quoted in Pierre Richard, “L’organisation syndicale traditionnelle est remise en cause par un groupe du sud-ouest,” Le Devoir, 14 October 1972. My translation.

75. Michaudville, ed., Les Gens du Québec (1), 30–31.

76. Renée Rowan, “Une publication sur le quartier St-Henri,” Le Devoir, 18 November 1972. My translation.

77. On the Italian context, see, for example, Steve Wright, Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism (London: Pluto Press, 2017). Similar developments could be found elsewhere in Canada, in the autonomous dissent being organized within the Canadian Auto Workers (caw) union in Windsor. Despite important grounding in New Left formations influenced by both Italian and American autonomous Marxism, the heart of this struggle was at the point of production, on the shop floor. See Sean Antaya, “The New Left at Work: Workers’ Unity, the New Tendency, and Rank-and-File Organizing in Windsor, Ontario, in the 1970s,” Labour/Le Travail 85 (Spring 2020): 53–89.

78. Des Travailleurs de C.C.M., Coleco, Lumiray, “Pour une information, formation, organisation, syndicales et politiques des travailleurs,” RG 116, 114, 521, Maison des Jeunes de St-Henri – Staff Reports, Company of Young Canadians Fonds, lac.

79. Langford, Global Politics of Poverty, 148.

80. “Quelques données ‘fait topiques’ sur les rapports entre le popir et les Travailleurs d’Accessories Manufacturers, et sur l’évolution de leur grève,” 21 August 1974, 165mi04.5.2, Comité ouvrier de St-Henri, Fonds du popir; Daniel Vinet, “Projet d’Organisation Populaire, d’Information et de Regroupement Inc. (P.O.P.I.R.): Document explicatif sur l’organisme,” 1974, 2, 165mi01.3.3, Comité directeur ou l’exécutif (1975), Fonds du popir; Procès-verbal: Réunion du Comité d’implantation de la Coopérative funéraire du Sud-Ouest de Montréal, 22 April 1975, 165mi01.3.6.1-2, Comité d’implantation de la Coopérative funéraire du sud-ouest Fonds du popir. The popir and other Saint-Henri groups were also affected by the divisions sweeping across grassroots groups in Montréal, caused by the increased influence of a variety of Maoist groups, and at least one popir employee lost his job because of his affiliation with the Ligue communiste. My sense is that the biggest impediment to mobilization, however, was the loss of funding. On Marxist-Leninists in Saint-Henri, see Christiane Bélanger, Carole Damiens-Panneton, and Mireille Girard, “Évolution et pratiques de l’animation sociale et des groupes populaires” (sv 1121, Faculté des Arts et Sciences, École de service social, Université de Montréal, April 1981), 44–46, 165mi.01.2.3, Études de stagiaires, Fonds du popir. On the impact of Marxist-Leninists in the Point, see Le Collectif CourtePointe, Pointe Saint-Charles: Un quartier, des femmes, une histoire communautaire (Montréal: Les Éditions du remue-ménage, 2006), 57–58. For general background on the phenomenon, see Jean-Philippe Warren, Ils voulaient changer le monde: Le militantisme marxiste-léniniste au Québec (Montréal: vlb Éditeur, 2007); Guillaume Tremblay-Boily, “Le virage vers la classe ouvrière: L’implantation et l’engagement marxistes-léninistes québécoises en milieu de travail,” PhD. diss., Concordia University, 2022; David St-Denis Lisée, “‘Le monde va changer de base: L’horizon international du groupe marxiste-léniniste En Lutte! (1972–1982),” ma thesis, uqam, 2019; Lucille Beaudry and Robert Comeau, eds., “Histoire du mouvement marxiste-léniniste au Québec, 1973–1983: Un premier bilan,” special issue, Bulletin d’histoire politique 13, 1 (Autumn 2004); Alexis Dubois-Campagna, “‘Pour un syndicalisme de lutte de classe!’: Les groupes marxistes-léninistes et le mouvement syndical au Québec, 1972–1983,” ma thesis, Université de Sherbrooke, 2009.

81. Le popir: Document de travail, Orientation et cadre de travail du popir, December 1976, 165mi01.2.2, Historique, Fonds du popir. My translation.

82. “saint-henri deux visages,” n.d. [c. 1974], 165mi04.3.5.1, Association des locataires de St-Henri, Fonds du popir. The Association des locataires du Montréal métropolitain was itself largely defunct by 1974. See Geneviève Breault, “Militantisme au sein des groupes de défense des droits des personnes locataires: Pratiques démocratiques et limites organisationnelles,” Reflets: Revue d’intervention sociale et Communautaire 23, 2 (Fall 2017): 183.

83. See the range of meeting minutes and working documents from 1980 to 1984 contained in folders 165mi01.3.5.5.1, Comité-logement (hlm) popir, and 165mi01.3.5.5.3, Comité des locataires du popir, Fonds du popir.

84. popir-Comité Logement, “popir: 25e Anniversaire, 1969–1994,” 5; 165mi02.2.17.2-2 sap (Services d’aménagement populaire) P.V. des congrès et colloques, Fonds du popir. See also Gilles Lauzon and Marcel Sevigny, “Le Service d’aménagement et les coopératives,” Logement et luttes urbaines 4, 44 (1980): 83–91.

85. See the range of 1977 meeting minutes of the committee of tenants working on creating social housing in the neighbourhood, in folder 165mi04.3.7, Groupe logement, popir St-Henri, Fonds du popir.

86. See René Morissette and Hanqing Qiu, “Permanent Layoff Rates in Canada, 1978–2016,” Statistics Canada – Catalogue No. 11-626-X, Economic Insights, no. 108 (June 2020); Tara Vinodrai, “A Tale of Three Cities: The Dynamics of Manufacturing in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, 1976–1997,” Analytical Studies Branch – Research Paper Series, Statistics Canada 11F0019 No. 177, November 2001.

87. creesom, Sud-Ouest: Diagnostic, 66–69, 99.

88. “Présentation du popir,” 1987, 165mi01.2.2, Historique, Fonds du popir. See also the variety of meeting minutes from 1982 in folder 165mi01.3.6.7-2, Maison du Reconfort, Fonds du popir. On the characteristics of women coming to popir, see “Réunion du 15 juin 1982 pour la formation du comité de coordination femmes du popir,” 165mi01.3.2, Comité des femmes, Fonds du popir.

89. Bélanger, Damiens-Panneton, and Girard, “Évolution et pratiques,” 16.

90. popir-Comité Logement, “popir: 25e Anniversaire, 1969–1994,” 4.

91. See the collection of promotional bulletins for popir activities from the period of 1986 to 1988 in folder 165mi07.2, Communique (popir Bonjour), Fonds du popir. For a brief introduction to this period, see Camille Robert, “Du ‘travail d’amour’ au travail exploité: Retour historique sur les luttes feminists entourant le travail ménager,” in Camille Robert and Louise Toupin, eds., Travail invisible: Portraits d’une lutte féministe inachevée (Montréal: Éditions du remue-ménage, 2018), 31–45.

92. Folder 165mi07.2, Communique (popir Bonjour), Fonds du popir; “Rencontre inter-organismes sur la question du logement privé à Saint-Henri et Petite-Bourgogne,” 8 April 1987, 165mi01.3.5.6, Table de concertation des organismes de St-Henri Petite-Bourgogne 1987, Fonds du popir.

93. The evolution of this discussion can be followed through the meeting minutes of the popir’s board of directors, especially from December 1987 onward, found in 165mi01.3.2, Conseil d’administration (1987–88), Fonds du popir; on the choice as it was pitched to members, see “Le popir a l’heure du choix,” popir Bonjour May 1988, 165mi07.2, Communique (popir Bonjour), Fonds du popir.

94. Jean-Marc Garneau, Le Programme Économique de Pointe Saint-Charles, 1983–1989: La percée du développement économique communautaire dans le Sud-Ouest de Montréal (Montréal: Institut de formation en développement économique communautaire, 1990), 3, cited (and translated) in Steven High, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence and Class (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022), 266.

95. High, Deindustrializing Montreal, 266. On the incarnation of this approach in the housing sector, see Simon Vickers, “From ‘Balconville’ to ‘Condoville,’ but Where Is Co-opville? Neighbourhood Activism in 1980s Pointe-Saint-Charles,” Labour/Le Travail 81 (Spring 2018): 159–186. On the development of the social economy approach, see also Pierre Hamel, Action collective et démocratie locale: Les mouvements urbains montréalais (Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1991), 152–181.

96. Cited in Favreau, Mouvement populaire et intervention communautaire, 123. My translation.

97. Kathey Lepage, “Congrès frapru: La Force de l’Action Collective,” frapru, 1990, Congrès 10, P16-410-10, Fonds Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (frapru), Centre d’archives et d’histoire du travail. My translation.

98. Direction d’habitation de la Ville de Montréal, “Soutenir le développement du logement social et communautaire: l’expérience de la Ville de Montréal,” presentation, 27 May 2015, Réseau Québécois des osbus en Habitation, 5, https://rqoh.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/153_ville_de_montreal_et_developpement_du_logement_social.pdf.

99. Jean-Pierre Wilsey, “non à la fermeture de nos quartiers; pas de Schefferville dans le Sud-Ouest,” Vie ouvrière 219 (August 1989): 24–26.

100. See Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement and Agence canadienne d’évaluation environnementale, Rapport de la commission conjointe fédérale-provinciale: Projet de decontamination du Canal de Lachine, September 1996, https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/acee-ceaa/En105-54-1996-fra.pdf.

101. Arrondissement du Sud-Ouest, Rapport synthèse de la consultation de 2010 sur le développement des abords du Canal de Lachine, March 2011, 6, http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/ARROND_SOU_FR/MEDIA/DOCUMENTS/RAPPORT%20SUR%20LA%20CONSULTATION%20PUBLIQUE.PDF.

102. See Louis Gaudreau, Gabriel Fauveaud, and Marc-André Houle, L’immobilier, moteur de la ville néoliberale: Promotion residentielle et production urbaine à Montréal (Montréal: Collectif de recherche et d’action sur l’habitat, 2021), 58–73.

103. Danielle Turgeon, “Renaissance du Canal de Lachine,” La Presse, 16 February 2002, Cahier J, 1.

104. Hélène Bélanger, “Revitalization of Public Spaces in a Working Class Neighbourhood: Appropriation, Identity and Representations,” Urban Dynamics and Housing Change: Crossing into the 2nd Decade of the 3rd Millennium, enhr International Conference, Istanbul, 2010.

105. “Présentation,” Château Saint-Ambroise, accessed 21 September 2021, http://www.chateaustambroise.ca/fr/Presentation/.

106. Laurence Clavel, “Le Quai des éclusiers – Luxe et confort, au bord de l’eau,” Le Devoir, 19 March 2005, https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/77328/le-quai-des-eclusiers-luxe-et-confort-au-bord-de-l-eau.

107. Louis Gaudreau, “Participer, mais à quoi? Les limites du partenariat local en matière de développement urbain,” Nouvelles pratiques sociales 23, 2 (2011): 93n7.