Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Article

“We Thought It Would Last Forever”: The Social Scars and Legacy Effects of Mine Closure at Nanisivik, Canada’s First High Arctic Mine

Abstract: Although mine closures are an inherent feature of extractive industry, they tend to receive less attention in the literature on deindustrialization than the closures of manufacturing and other heavy industries. Until recently, the settler-colonial context of hinterland mineral development and its impact on northern Indigenous lands and communities in Canada have also remained largely unexplored within this literature. Mineral development is historically associated with the introduction of a colonial-capitalist industrial modernity across Canada’s northern regions. Yet the boom-and-bust nature and ultimate ephemerality of mineral development has meant that resource-extractive regions have also been subject to intensive “cyclonic” periods of closure and deindustrialization. This article examines the experience of deindustrialization on the part of the Inuit community of Arctic Bay, who were largely “left behind” by the closure of Nanisivik, Canada’s first High Arctic mine. Through documentary sources and oral history interviews we illustrate how, for Arctic Bay Inuit who were engaged in the cyclonic economies of Nanisivik’s development and closure, there were myriad dimensions of social loss, displacement, and resentment associated with the failure of this industrial enterprise to deliver promised benefits to Inuit, beyond more commonly understood socioeconomic impacts such as job loss.

Keywords: deindustrialization, mining, mine closure, Arctic, Northern Canada, Inuit, Indigenous communities, industrial colonialism, ruination

Résumé : Bien que les fermetures de mines soient une caractéristique inhérente de l’industrie extractive, elles ont tendance à recevoir moins d’attention dans la documentation sur la désindustrialisation que les fermetures d’industries manufacturières et d’autres industries lourdes. Jusqu’à récemment, le contexte colonial de l’exploitation minière de l’arrière-pays et son impact sur les terres et les communautés autochtones du nord du Canada sont également restés largement inexplorés dans cette documentation. Le développement minier est historiquement associé à l’introduction d’une modernité industrielle capitaliste coloniale dans les régions du nord du Canada. Pourtant, la nature en dents de scie et l’éphémère ultime du développement minier ont fait que les régions d’extraction de ressources ont également été soumises à des périodes « cycloniques » intensives de fermeture et de désindustrialisation. Cet article examine l’expérience de désindustrialisation de la communauté inuite d’Arctic Bay, largement « laissée pour compte » par la fermeture de Nanisivik, la première mine canadienne dans l’Extrême-Arctique. Grâce à des sources documentaires et à des entrevues d’histoire orale, nous illustrons comment, pour les Inuits d’Arctic Bay qui étaient engagés dans les économies cycloniques du développement et de la fermeture de Nanisivik, il y avait une myriade de dimensions de perte sociale, de déplacement et de ressentiment associés à l’échec de cette entreprise industrielle à livrer les avantages promis aux Inuits, au-delà des répercussions socioéconomiques mieux comprises comme la perte d’emploi.

Mots clefs : désindustrialisation, exploitation minière, fermeture de mine, Arctique, Nord du Canada, Inuit, communautés autochtones, colonialisme industriel, mise en ruine

Writing to the Nunatsiaq News in the wake of the 2002 closure and decommissioning of the nearby Nansivik lead-zinc mine and community, Arctic Bay resident Mishak Allurut expressed the sense of bitterness and betrayal felt by many in his north Baffin Island, Nunavut, community: “My two daughters have birth certificates from Nanisivik. The school there is named after my father. Nansivik was a temporary community with no real status. Yet, lives were lived and life continues even in the midst of being demolished or vaporized. So, my daughters’ birth certificates are temporary? Thank you Nanisivik Mines Ltd. for everything.”1 In spite of the mine’s failure to reach ambitious targets for northern employment during its 26-year operation, for some the community of Nansivik had become an important part of the region’s landscape and economy. The mine’s closure and the depopulation of the community came as a shock to many Arctic Bay Inuit, as Elder Koonoo Oyukuluk recalled in an interview nearly a decade later: “We didn’t realize that it was a temporary establishment … we thought it would last forever.”2

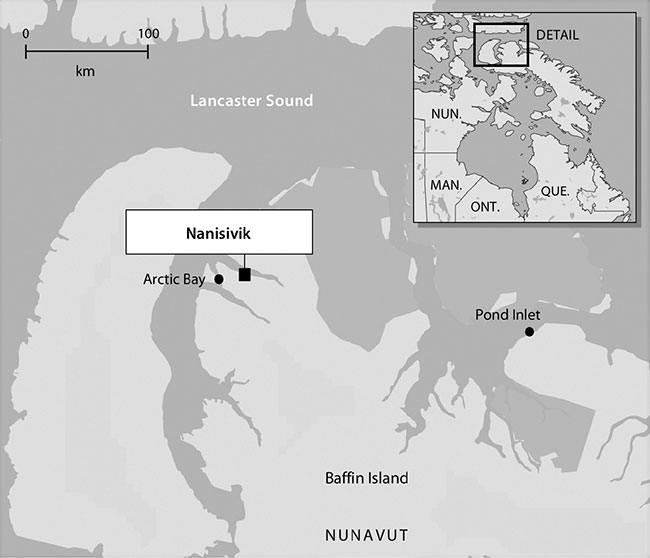

These reflections by residents of Arctic Bay capture the painful, lingering, at times paradoxical experience of deindustrialization associated with mine closure, even among regional residents only indirectly involved in or affected by this remote industrial installation. The Nanisivik lead-zinc mine, Canada’s first High Arctic mine, operated from 1976 to 2002 on the shore of Strathcona Sound on the northern tip of Baffin Island (Qikiqtaaluk), approximately 30 kilometres by all-season road from the nearby Inuit community of Arctic Bay (Ikpiarjuk) (Figure 1).3 Constructed with the support of the federal government as an “experiment” in High Arctic mining, the Nanisivik development included an underground mine, mill facility, and purpose-built townsite to house the mainly southern-based workforce.4 The development also aimed to introduce local Inuit to industrial wage labour by setting training and employment targets. Despite several extensions of its initial twelve-year mine life, like all mines Nanisivik eventually wound down operations, inaugurating a difficult closure and deindustrialization process that resulted in the complete demolition of the settlement, the relocation of most of the residents, and a contested environmental reclamation process.

Figure 1. Map of Arctic Bay and Nanisivik.

© OpenStreetMap contributors.

This article examines the experience of deindustrialization on the part of regional Inuit who were largely “left behind” by Nansivik’s closure. Mineral development is historically associated with the introduction of a colonial-capitalist industrial modernity across Canada’s northern regions.5 Yet the boom-and-bust nature and ultimate ephemerality of mineral development has meant that resource-extractive regions, particularly those remote from “core” industrial capitalist regions, have also been subject to intensive “cyclonic” periods of closure and deindustrialization.6 The impacts of mine closure and deindustrialization are frequently (and rightly) understood mainly in terms of socioeconomic impacts such as job losses, outmigration, and economic dislocation.7 However, through documentary sources and oral history interviews, we illustrate how, for Tununirusirmiut (people of the Arctic Bay region) who were engaged in the cyclonic economies of mineral development and closure, there were myriad dimensions of loss beyond economy and employment that were vastly more important and enduring.

Although mine closures are an inherent feature of extractive industry, they tend to receive less attention in the literature on deindustrialization than the closures of manufacturing and other heavy industries. The main focus of this scholarship to date has tended toward manufacturing and factory closures in Rust Belt and other core or “heartland” areas where deindustrialization has been most visible.8 The few studies that have addressed mining contexts have tended to focus on single-industry “mining towns,” typically around coalfields.9 Across these investigations, Jim Phillips argues, “The chief economic and social problem arising from deindustrialization [has been] the loss of relatively well-paid manual employment for working-class people with comparatively limited educational qualifications.”10 Nevertheless, as Sherry Lee Linkon expresses in terms of her notion of the “half-life of deindustrialization,” “Its effects remain long after abandoned factory buildings have been torn down and workers have found new jobs. … We see the half-life of deindustrialization not only in brownfields too polluted for new construction but also in long-term economic struggles, the slow, continuing decline of working-class communities, and internalized uncertainties as individuals try to adapt to economic and social changes.”11

We also see a form of this “deindustrial half-life” persisting long after closure and remediation in northern Indigenous communities like Ikpiarjuk, thought to be largely marginal or excluded from the economic and employment benefits of mining. We explore these experiences in the context of the historical (and ongoing) settler-colonial relations that shaped capitalist industrial development on Canada’s northern extractive frontier. From this perspective, closure and deindustrialization are associated with communities’ experiences of broader economic and social changes, where the benefits of extractive development may have been ephemeral but the collateral impacts of deindustrialization are very real. In particular, unlike mobile workers (and capital) recruited from outside the region and departing with closure, Indigenous peoples such as the Tununirusirmiut of Ikpiarjuk “are intimately and permanently connected to their ancestral homelands and they will bear the cost of environmental and other legacies of mining, possibly for many generations.”12 We also illustrate the deep senses of social loss, displacement, and resentment associated with the failure of this industrial enterprise to deliver the promised social and economic benefits to Inuit communities. These experiences continue to resonate with Tununirusirmiut, even as they navigate renewed and prospective industrial mineral development in their homelands.

Northern Mining, Closure, and Deindustrialization

In considering the intersection of mining and deindustrialization in Canada, we draw on work in the “new economic geography” that extends the staples theory of Harold Innis to call for a re-emphasis on “resource peripheries” and expands Innis’ concept of “cyclonic” development patterns to describe the sheer intensity of economic and cultural change in resource regions.13 Cyclonics refers to “the idea that hinterland resource developments proceed in a storm-like fashion, with a sudden flood of capital, labour, materials, and knowledge into remote areas [which then] dissipates just as quickly when conditions change.”14 The cyclonic metaphor helps to challenge the all-too-common narrative of economic booms and busts as a “natural” part of the mineral “resource cycle.”15 Cyclonic patterns also help to explain the “dramatic transformations of landscape, environment and social relations on Canada’s northern mining frontier” – including those wrought by closure and deindustrialization.16 Work in this area marks a dramatic shift in economic assumptions and conditions relating to deindustrialization: from industrial cycles of development and decline to the unique conditions of remote, sudden single-industry communities. Economic dislocation and other changes in resource peripheries must be understood differently than industrial and core communities experiencing deindustrialized decline.17

Until relatively recently, however, the settler-colonial context of hinterland mineral development (and subsequent decline) and its impact on northern Indigenous lands and communities in Canada remained largely unexplored within the deindustrialization literature. By settler colonialism, we refer to the widely theorized concept denoting the historical and contemporary relations between Indigenous peoples and colonial states such as Canada, the United States, and Australia that are “rooted in the elimination of Indigenous peoples, polities, and relationships from and with the land.”18 This ongoing process entails not merely the removal of Indigenous peoples and their demographic replacement by white settler communities but also the disruption of Indigenous cultures and lifeways through resource appropriation and environmental degradation.19 Indeed, despite mining in Canada invariably taking place in the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples, the staples-inflected literature largely focuses on experiences of boom and bust in non-Indigenous mining towns.20

Steven High’s work on “mill colonialism” in Northern Ontario represents one of the few exceptions, shifting attention from deindustrializing cores to examine deindustrialization on the resource periphery, where the “culture of industrialism was a product of wider processes of Euro-Canadian colonization and the racial[ized] exclusion of Indigenous peoples.”21 This work, focusing mainly on the Franco-Ontarian mill town of Sturgeon Falls, is centred on the experiences of workers (few of whom were Indigenous) and does not include members of the Nipissing First Nation or their adjoining community of Garden Village. Ultimately, this work critically recognizes, drawing on the work of Ann Laura Stoler, that ruination associated with deindustrialization at the industrial frontier is an “act perpetrated, a condition to which one is subject, and a cause of loss.”22 That is, the same capitalist processes that have created colonized resource peripheries such as Northern Ontario have also caused the ruination that follows.23

Other recent scholarship on mineral development and its legacies has begun to interrogate the relationship of mines to the introduction of industrial colonialism in the Canadian North.24 Drawing on scholarship in environmental justice and political ecology, Arn Keeling and John Sandlos develop a framework for exploring the historical links between “political economy, state-led or promoted development projects, and the settler colonial dispossession of indigenous people.”25 From this perspective, the historical experiences of colonial dispossession, economic and social marginalization, and environmental degradation arising from large-scale mineral development continue to shape settler-Indigenous relations on Canada’s extractive frontiers. The experiences of displacement and injustice, however, are not confined to mining development and operation but extend to the closure and post-mining phases.26 For instance, diverging from much deindustrialization scholarship examining social histories of mine closure, Heather Green found that the Polaris Mine in Nunavut and its closure held little economic or social importance to Inuit in nearby Resolute Bay and that the mine was in fact largely absent from any collective memory. Significantly, “the exclusion and marginalization of Resolute itself left the community with no strong ties to Polaris.”27 From the perspective of Indigenous environmental justice, the experiences of mine closure and deindustrialization may reinscribe ecologies of industrialization that tended to sever or harm the relations and activities of Indigenous peoples with their lands and territories.28 In this sense, mine closure and deindustrialization represent not simply the absence or retreat of industrialism but its ongoing legacies for local landscapes and communities.29

Study Setting and Methodology

This study included community-based fieldwork in Arctic Bay between July and September of 2011. The population of Arctic Bay in 1972, around the time of Nanisivik’s feasibility study, was about 300.30 As of 2021, it has a population of 994, with 97 per cent of residents identifying as Inuit and 93 per cent stating Inuktitut as their first language.31 Arctic Bay pre-dates Nanisivik by almost 50 years, as it was initially established by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1926, though the area had been inhabited and utilized by Inuit for thousands of years.32 Nanisivik was the largest employer in the region, and comparable economic activity has not resumed near Arctic Bay since the mine’s closure in 2002. Nonetheless, the community has long been strongly supported by the traditional or land-based economy, and in 2006, 82 per cent of Inuit adults in Arctic Bay reported hunting, 86 per cent reported fishing, and 78 per cent reported gathering wild plants in the previous year.33

Interviews (n=29) conducted by Tee Lim with former mine employees and their family members, Elders, hunters, and other community members explored participants’ experiences and perspectives in relation to the mine development, operation, and particularly deindustrialization in the decade or so after the closure of Nanisivik. We also spoke with current and former government and industry personnel involved with the Nanisivik mine. A highly experienced local interpreter was engaged as the community research associate, assisted with the identification of research participants, and enabled a number of interviews to be conducted in Inuktitut. Most of those interviewed lived in Arctic Bay, the community most proximate to the former Nanisivik mine site. Purposive, directed sampling was employed as we sought both those who worked at, and others who remembered the mine and its eventual closure. This included custodial employees, skilled tradespersons (e.g. a carpenter), underground miners and heavy equipment operators, former residents (e.g. those who were born and raised in or grew up in Nanisivik), and descendants of the first Inuk foreman, as well as those in Arctic Bay who could speak to but did not work or live at Nanisivik (e.g. Elders whose opinions were often sought on matters of community development and change). An open-ended, semi-structured interviewing approach was used that generated descriptions of experiences and perspectives in relation to Nanisivik. Topics raised included community life before the mine, its development and operation, its status as an employer, the influence of wage earnings or any other changes introduced by the mine, its infrastructure, and the experience of and reflections on closure in reference to both decisions made and actions taken at the time.

The project was approved by the ubc Behavioural Research Ethics Board and the Nunavut Research Institute and, unless otherwise noted, interviewees are publicly named according to their preference. During a community workshop (n=46), participants were presented with and discussed preliminary findings and communicated recollections, concerns, and understandings of Nanisivik’s life cycle, as well as of the research project itself. This workshop, considered an important component of the study’s community accountability, was described by the local research associate as a good precedent; he said such report-backs were rare among researchers visiting Arctic Bay.34

These interviews were supplemented by an analysis of various media articles (especially from Nunatsiaq News, Nunavut’s territorial newspaper), existing literature, and government, regulatory, industry, and community studies and documents pertaining to Nanisivik, Arctic Bay, and Arctic mineral development. In particular, the comprehensive records of the Nunavut Water Board (nwb), the regulatory agency overseeing Nanisivik’s closure, were examined extensively. These records included Nanisivik’s closure plans and reports, submissions by interveners and other stakeholders, and full transcripts of public hearings held in Arctic Bay in 2002, 2004, and 2009. All of these records, together with the oral history interviews in 2011, allowed for analysis and comparison of community attitudes right through the mine’s closure and post-closure phases. To understand the mine’s origins and background, the archival record of the project’s development, held by Library and Archives Canada, was consulted.

Nanisivik: “The Place Where People Find Things”

Beginning with the North Rankin Nickel Mine (1957–62) on the Arctic coast of Hudson Bay and later the Asbestos Hill Mine (1972–84) in Arctic Québec, the federal government promoted “experimental” mines aimed at introducing wage labour and industrial economies to Canada’s Arctic territories.35 In the 1970s, the government sought to extend this vision of industrial modernity to the High Arctic through its extensive planning and material support for both the Nanisivik and, later, Polaris mines.36 The Nanisivik mine was established via the 1974 Strathcona Agreement between Canada and Calgary-based company Mineral Resources International (mri). In return for grants and loans for infrastructure construction, the state received an 18 per cent equity interest in Nanisivik Mines Ltd.37 and imposed a number of requirements, including 60 per cent employment of “northern residents” (in effect Inuit) by year three of production, a minimum production life of twelve years, special training programs, and environmental studies.38

Table 1. Government Contributions to Project Costs (in Millions)

|

Item |

Total outlay – actual |

Expected recovery – actual |

Residual – actual |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Townsite |

$19.9 |

$9.9 |

$10.0 |

|

Airport |

$5.2 |

$0.0 |

$5.2 |

|

Roads |

$3.9 |

$0.0 |

$3.9 |

|

Dock |

$2.4 |

$1.8 |

$0.6 |

|

Total |

$31.4 |

$11.7 |

$19.7 |

Source: Neil R. Burns and Michael Doggett, “Nanisivik Mine – A Profitability Comparison of Actual Mining to the Expectations of the Feasibility Study,” Exploration and Mining Geology 13, 1–4 (2004): 125.

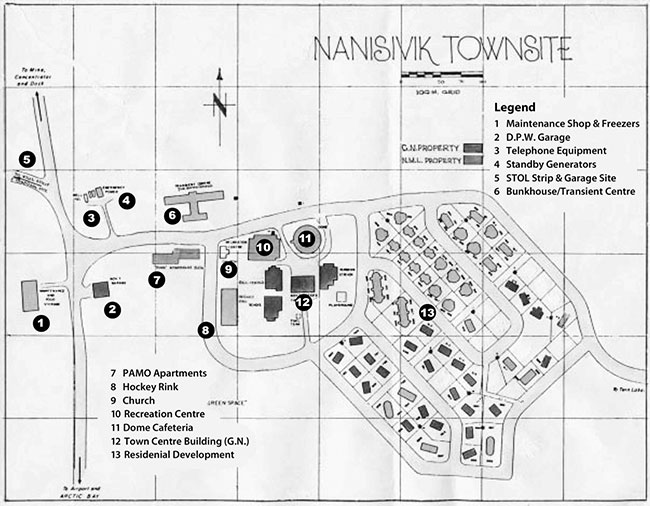

Government investment of $31.4 million (Table 1) supported construction of an airport, deepwater dock, all-season road to Arctic Bay, and the Nanisivik townsite. Canada expected to recover $11.7 million through repayments and user charges, leaving a residual of $19.7 million – over 2.3 times more than the original feasibility study figure of $8.5 million.39 At closure, infrastructure belonging to the federal and territorial governments included a garage, a town centre complex including housing, recreational facilities, a town hall, library, civic service buildings, and potable water, as well as utilidor sewage systems.40 Infrastructure belonging to CanZinco (the mine’s final operator) included mill facilities, storage buildings, an emergency power plant, a large dome cafeteria, and a fuel tank farm. Housing consisting of residential units, an apartment complex, and a bunkhouse, capable of accommodating approximately 400 people, was also owned mainly by CanZinco and the Government of Nunavut (gn) (see Figure 2).41

Figure 2. Map of Nanisivik townsite.

Source: Consilium Nunavut Inc., “Alternative Use Options for the Nanisivik Mine Facilities: Final Report”

Iqaluit: Consilium Nunavut Inc., 2002, 14.

With Nanisivik, as with Rankin Inlet before it, Canada aimed to advance the industrial development and modernization of the Arctic, reducing both welfare expenditures and operating costs for mines through assimilation of Inuit into a settled and trained labour force.42 This workforce was expected to move to new communities, or commute from industrial development to development in the future, completely discounting Inuit connections to the land and its resources: “It was assumed that many … would leave their relatives, their home villages, and their land – the land with which they were familiar and in which they had carried out their traditional activities.”43 But as with earlier developments, at Nanisivik little heed was paid to the implications of integrating Inuit into the dominant, southern Canadian industrial economy and culture or moving the region rapidly from a “traditional” land- and marine-based economy to a heavily wage-based mixed economy.44 While Nanisivik achieved one of the highest Indigenous employment rates across mines in northern Canada, in its 26 years it still fell short of the 60 per cent target by more than half, peaking at 28 per cent. Employment was highest early in production (1978 to 1980), averaging closer to 23 per cent. Toward the end of the mine’s life, average Inuit employment was just 10 per cent between 1999 and 2001.45

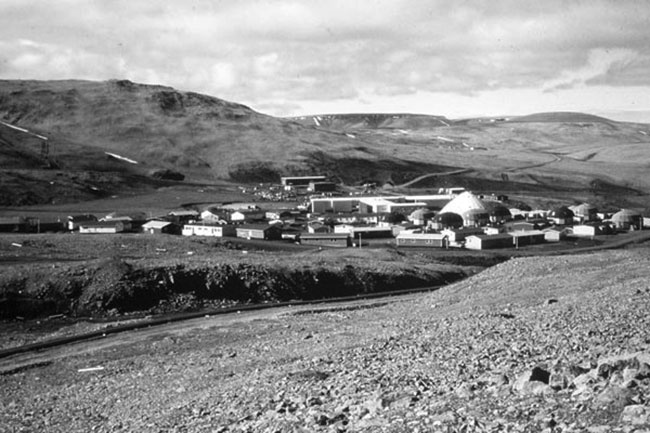

Figure 3. Nanisivik townsite, 1991.

Photo by Bob Wilson. Reproduced by permission from NWT Archives, Northwest Territories Department of Public Works and Services fonds, G-1995-001, 1379.

While a 60 per cent Inuit employment rate may have been considered a laudable goal – or an ambitious attempt at proletarianization – Nanisivik’s project manager dismissed the target as a “magic and completely haphazard figure,” one that the government insisted on “solely to satisfy certain groups in southern Canada.”46 Indeed, if the primary purpose of the mine seemed to be “donating a mineral deposit for the purpose of employing some Inuit,” its success was marginal at best. It was also argued during project assessment that the estimated government assistance of $167,000 per Inuk employed would be better spent on employment where Inuit could be supported more directly, without the corporate risk of the mine and the possibility of worker relocations at both the start and finish of the project.47 This prescient analysis came to be confirmed by a later socioeconomic impact study, which concluded that “public investment in Nanisivik that was rationalized for its potential to contribute to regional development could have had greater developmental impacts had it been spent directly on local development capacity-building.”48

The Evolving Trajectory of Closure and Loss

In what follows, we examine both the closure and post-closure phases of the Nanisivik mine, while highlighting the experiences of the people of Arctic Bay – in particular, Inuit experiences of deindustrialization in the decade or so after mine closure. We argue that Nanisivik differs markedly from economic models of deindustrialization in that the arrival of mining provided only limited local employment and investment, meaning loss of employment was a less locally significant impact. The ethnically stratified workforce that developed over 30 years certainly included some Inuit labour, which meant that local workers from Arctic Bay were indeed affected by Nanisivik’s closure. However, two socioeconomic impact studies concluded that Nanisivik contributed little in terms of long-term economic or social development in Arctic Bay or to the community’s capacity to achieve its own development goals.49 Major public investment in the Nanisivik mine was justified by expectations that it would fuel regional employment and development, yet this has evidently not been the case. One study concludes, “As it stands, it is almost as if the mines had never existed, so few are the lasting positive impacts of the mines.”50 Rather, Tununirusirmiut experienced mine closure primarily through the lens of their marginalization from benefits and the destruction of Nanisivik itself.

The failure to promote large-scale Inuit employment at Nanisivik nevertheless still featured in post-closure Inuit recollections of the experience of both work and job loss at the mine. Racism and discrimination, for instance, permeated relations between mine managers and Inuit employees. For example, in 1977, Nanisivik’s project manager stated bluntly that he only hired Inuit workers because he had to, as “from the point of view of effectiveness and thus productivity,” he would prefer to hire white workers.51 Nor was the prevalent racism lost on Inuit employees from Arctic Bay – including their full awareness of the need for “upskilling” to suit the needs of the assimilation agenda presumed by the state.

In the very beginning for me, just learning how to speak English was very hard, and just being around people – at least 80 per cent of the population were English speakers, so we had no choice. And so having to speak it all the time was really hard at first … the supervisors, they wouldn’t treat their employees fairly, there was meant to be 60 per cent Inuit employment, that never ever happened, it was always like 20 to 25 per cent. And whenever someone reminded them, I overheard a couple of … managers saying no, why should we be hiring Inuit because they drink all the time, they party all the time, they’re never on time. That was always their attitude towards Inuit … why even bother working for the mine when they look down on the Inuit a lot, and they don’t try and think of the positive.52

Concerns about employment levels, training, and turnover featured prominently in our interviews. Most of these memories focused on the failure to leave a legacy of lasting skills that would be useful in the northern Arctic. Reflecting on the lack of training, and local desires for advancement, Arctic Bay resident and former Nanisivik custodial worker Mishak Allurut lamented, “If they promise something – that they’ll train Inuit – and they’ll provide employment by teaching us the trades, they should be more open to that. So my question would be how come they’re more interested in making money than teaching us careers for the future? If you plan to teach local people skills or a career, stick with that, and not hire them as a janitor all their life, because they want to advance too.”53

The majority of Inuit employees worked instead in manual and semi-skilled roles that required minimal training and education, with most men employed as seasonal labour during the summer shipping season, and most women employed in housekeeping and cleaning positions.54 In 1979, the turnover rate was 106 per cent for Inuit males, compared with 63 per cent for southern male workers.55 This substantial difference is partly explained by the fact that for Inuit, employment was not motivated by the wage labour–based development model the state imagined; instead, it was a potential means to acquire goods that enabled continuity of their land-based economy. In this context, Western education, training, and work experience was comparatively irrelevant for many Inuit. High turnover among Inuit employees had much more to do with their own agency and preferred mixed-economic existence within, and resistance to, the industrial interests the state sought to impose.56 Consistent with George Wenzel’s findings on Inuit from Clyde River who worked at Nanisivik, Arctic Bay residents reported that local people would often simply work long enough to recapitalize themselves and their families for hunting and land-based activity.57 Similarly, other studies on the North identify the willingness of Indigenous peoples to take advantage of wage labour opportunities in mining when available but to also simply quit when hunting or fur prices were favourable.58

This is not to say that residents of Arctic Bay interviewed in 2011 ignored the struggles of those who lost their jobs at closure, including loss of hope and “outlook for the future.”59 But this loss was linked primarily to the reduced ability to purchase food and hunting equipment necessary for continuity of land-based activities. Utilizing mining wages to support land-based activity was repeatedly mentioned as a foremost priority. Elder Sakiasie Qaunaq explained, “Their income would go into the purchase of capital items, like skidoos, boats, or any equipment that they need. If an Inuk gets some big amount of money, the first thing they’ll think about is hunting equipment.”60 Though such equipment was rarely shared beyond immediate family, systems of country food sharing – a central feature of the Inuit social economy – remained prevalent.61 As another Elder described, “It was not so much sharing of the equipment, but the worker would go hunting and bring back the catch, and would be sharing that with the community.”62

In Search of Economic Diversification and Alternative Site Use

In fact, loss of jobs and income was not the main source of strong reactions to Nanisivik’s closure among local Inuit. Nor were severe ecological concerns and legacies, frequently the focus of scholarship on mining impacts. Instead, the profound effects on the residents of Arctic Bay of decommissioning and demolition of highly valued industrial and residential infrastructure at Nanisivik emerged as the leading impact of closure. These issues were experienced as the final slight in a long history of marginalization in relation to Nanisivik including, ironically, an emerging focus on health and environmental concerns through closure and post-closure. In regulatory reviews and at public hearings into mine closure in 2002 and 2004, the nwb and the Nunavut Impact Review Board (nirb) focused overwhelmingly on health and environment, neglecting socioeconomic concerns that should have explicitly been part of nirb’s mandate.63

While, as noted, motivations of Inuit choosing to (selectively) engage in mine work are complex, on its own terms the failures of Nanisivik to deliver on promises of employment and industrial prosperity for Inuit were magnified as closure loomed in the early 2000s. Nanisivik’s 26 years of operation were more than double the original project life agreed to, with exploration leading to ore-body extensions.64 CanZinco announced final closure of operations in 2001, to be implemented by 2002.65 The company cited exclusively economic reasons, including “continuing depressed metal prices” and zinc prices being at a “historic low.”66 The gn Minister for Sustainable Development, Olayuk Akesuk, indicated he was “sure we’ll come up with something, we still have 11 months to come up with a plan,” adding that the mine’s legacy was of clear concern.67 Central in this period was the importance of asset preservation prior to mine closure.68 CanZinco seemed in agreement, with Nanisivik’s general manager stating, “We would like to leave a positive legacy. We believe that Arctic Bay can benefit from things at the mine … Daycare, school, health and other equipment – we’ll transport it to Arctic Bay.”69 Arctic Bay’s own expectations were equally clear; as Mayor Joanasie Akumalik said, “The community doesn’t want to see it just bulldozed and covered. They’d like to see something happen with the mine site.”70

While CanZinco expressed interest in finding some alternative use for the town’s infrastructure, it was nonetheless upfront in stating that unless indemnities for ongoing use of mine facilities were in place, it intended to sell what it could and dispose of the rest. The company wished to proceed quickly with reclamation activities because of legal requirements, as well as a desire to minimize “care and maintenance” costs and environmental liabilities incurred through delay.71 Initially, however, CanZinco regarded this possibility as a “tragedy” and appeared “confident that this travesty will not be permitted to occur.”72

Nevertheless, despite an almost twenty-year lead time to prepare for Nanisivik’s closure, including closure reports and alternative site-use plans dating back to the 1980s, effective economic diversification measures were not implemented. A vocational or multi-purpose training centre, a correctional centre, and a military facility were all options considered for the Nanisivik site.73 However, all were ultimately deemed economically infeasible.74 The community had initially thought it “seemed a certainty” that a training centre would be established as an economic diversification measure at Nanisivik, but the gn concluded “funds would be better invested in people, and training, not buildings.”75 CanZinco appeared exasperated at the failure to negotiate an agreement with the gn over Nanisivik’s infrastructure, and its earlier optimism around finding another use for the Nanisivik site waned until it was “pretty much extinguished.”76 According to CanZinco president Bill Heath, “We were of the view that there was still some life left in those buildings. We’ve been trying very, very hard for almost five years to find some alternative purpose for Nanisivik that would allow the infrastructure to stay in place. It’s really the people of Arctic Bay who are going to pay the biggest price for that decision.”77

For its part, the gn raised the possible dangers to human health (particularly for toddlers and children) as justification for not pursuing alternative site uses. At the 2004 hearing on the closure, the gn’s legal counsel suggested that uncited “studies of the houses and the soil and the buildings at Nanisivik showed levels of lead and certain other metals which could be dangerous to … health.”78 However, these claims appear unsupported by the scientific evidence: a 2003 “human health and ecological risk assessment” had determined that cadmium, lead, and zinc exposure point concentrations were lower than the soil quality remedial objectives.79 A reviewer and ecotoxicologist also suggested that the buildings at the mine site did not appear to pose health risks.80

If there were genuine concerns regarding contamination, it is certainly troubling to think that Nanisivik’s residents were not made aware of it. While gn health officials initially deemed the lead levels in the community safe, the territory’s chief medical officer of health, Geraldine Osborne, later suggested that the lead and cadmium levels were not considered safe and recommended further risk evaluation.81 Mayor of Arctic Bay Niore Iqalukjuak thus raised the question: If housing units previously moved to Arctic Bay from Nanisivik in 1996 were indeed contaminated, what were the effects then on Tununirusirmiut?82 No answer was forthcoming. In spite of these apparent concerns about repurposing contaminated buildings, CanZinco sold much of the mine infrastructure (including the mill and storage facilities) to Wolfden Resources (owners of a property in Nunavut) for relocation and use elsewhere.83

Seeing through Excuses and the Abandonment of Arctic Bay

With an alternative site use at Nanisivik seemingly off the table, by 2004 interest had turned to relocation of some of the mine and town buildings to Arctic Bay. Tununirusirmiut at least expected to salvage some infrastructure, including housing and furniture. Mayor Iqalukjuak decried the social injustice that housing demolition would represent, expressing desire for salvage of the units – either whole or for materials – and the willingness of residents to do the work themselves: “just burning the units in Nanisivik is just too unbearable.”84 Yet building contamination was again used as the primary justification for the gn choosing not to relocate any buildings. As a newly formed governing body, taking on the risk assessment and decision analysis needed for lead contamination in particular was not an easy task. Thus, the gn claimed that relocation of housing units to Arctic Bay was “neither logistically nor economically feasible,” pointing to elevated lead dust levels in housing and the “special cleaning” required to decontaminate residences.85 The gn claimed that relocation costs would exceed $900,000 per house.86 Removing lead is indeed a costly act of remediation. However, when ten houses were previously moved from Nanisivik to Arctic Bay in 1998, the cost per unit was $239,080, with most costs relating to retrofitting and rehabilitation.87

With all economic diversification options deemed “non-viable,” in July 2004 the nwb thus approved CanZinco’s 2004 Reclamation and Closure Plan, including full demolition and reclamation of the townsite.88 Over $50 million worth of industrial and residential infrastructure at the mine and townsite was demolished. The nwb correctly observed that it had no mandate to consider “jobs, social and economic impacts, environment and all other issues,” instead describing its responsibilities as “water and waste.”89 Yet while nirb acknowledged the “pervasive impact [of Nanisivik] on the lives of the local population,” no mention of socioeconomic concerns was made in the specific terms and conditions it set out for the mine’s closure. Instead, despite a mandate to include socioeconomic matters in its reviews, nirb focused overwhelmingly on environmental concerns around tailings management.90

The demolition of Nanisivik’s townsite and infrastructure had a haunting effect on residents of Arctic Bay. It figured prominently in the 2009 public hearing transcripts of the nwb review of CanZinco’s water licence renewal and amendment application and in all of the 2011 interviews, more than five years after the major site reclamation had ended. People’s deep disillusionment with the sheer waste of rare material assets reflected the concerns of a community long compromised by poor-quality infrastructure and housing. As Tootalik Ejangiaq described, “it was heavy for me especially when you leave here … by demolishing and throwing away usable materials, it is hard to take. We have a housing shortage, but then at the same time, you just demolish and throw away usable houses.”91 Retired carpenter Sakiasie Qaunaq observed that “the built condition of some of the units were even better than the ones we have here in [Arctic Bay].” The comment about conditions is not hard to believe; in 2006, more than half of Arctic Bay’s dwellings had been constructed before 1986, and roughly one-third were in need of “major repair.”92 Former underground miner Jonah Oyukuluk stated, “Twice, they offended us. Firstly, they didn’t compensate us for the damage they did to the environment or for the contamination of the land. Besides that, they didn’t want to give us any of the materials or buildings or furniture, so it was like a double-edged offense.”

The contested assertions of contamination contributed to a sense of mistrust, even betrayal, among Tununirusirmiut. As Piuyuq Tatatuapik argued before the nwb, “I don’t think Nanisivik buildings are contaminated … we had workers there who were cleaning the houses regularly.” At the 2004 hearing, former mine worker Tommy Kilabuk directly pressed the gn’s legal counsel for her evidence of any potential health risks: “in some ways I don’t really trust the government … the Inuit who had children in Nanisivik, is there any evidence of that child, when they are born, having any liver or internal illnesses?”93 Similarly, in 2011 interviewees remained unconvinced by the contamination threat, either stressing that this was simply what they had been told or emphasizing the inconclusiveness of the stated contamination. Elder Olayuk Kigutikajuk observed, “We were told [emphasis added] that the buildings were too contaminated to be brought here, so the contamination was the problem – why they didn’t give us any buildings.”

On the whole, residents seemed well aware of the desire by both the gn and CanZinco to avoid liability concerns. One Elder and hunter distinguished between the treatment of infrastructure at the production and expansion phase of the mine versus the closure phase: “When it was upgrading … all the equipment and the buildings seemed to be okay. But when they were closing they said they are hazardous or contaminated, therefore they demolished them.”94 As Mishak Allurut observed, “I think they just wanted to get rid of it, and not be held liable. I think they were protecting themselves more. Or they didn’t want to pay for moving it here.” Former Nanisivik resident Kataisee Attagutsiak raised similar concerns: “I was saying, ‘why on earth are you guys destroying all of the houses and the furniture,’ [and] they said it was because they don’t want to be sued if there was any high content of lead levels or any contaminants in the housing. How come that’s an issue though, does that mean we all have contaminants since we lived there for many years? So where is the truth?”95

Residents also expressed that beyond the language difficulties associated with negotiating in English, other cultural differences (including financial ones) hindered Arctic Bay’s efforts to gain infrastructure. One Elder stated, “Inuit culture and tradition is different from Qallunaat tradition and culture, and since Inuit didn’t have any money back then that’s why they didn’t get anything they couldn’t buy.”96 Indeed, Inuit found themselves criminalized for salvaging materials from the site, as Tootalik Ejangiaq indicated, which contributed to their sense of frustration and injustice: “We were even charged with criminal acts, like taking property, after it closed down … being Inuit not knowing the Qallunaat way. We didn’t know that it was illegal or, somehow impossible I guess to take them, due to regulations or laws. … When you don’t speak English … the bureaucratic system made it impossible for us to get our views across. But they just told us, ‘Go to that person.’ And when we go to that person, they say, ‘Go to that person.’”97

For some Inuit, the sense of loss and alienation following the mine closure was more than material in nature – its ruination, in this sense, was a “cause of loss.” The closure and destruction of the town resonated deeply, not only for the failed promises of Arctic industrial development, but for the loss of community and sense of place that had developed.98 More than simply a workplace or a townsite made up of infrastructure, Nanisivik was also a community in all senses of the word. Its former Inuit residents expressed a sense of sadness and loss over Nanisivik’s absence, as well as memories evoked by the place. Sakiasie Qaunaq reflected, “I recall the time Nanisivik was full of life. But when I went there after the mine closed and saw the vacant, empty lot where the community used to be, I got emotional about it. I missed it.” (See Figure 4.) Sheena Qaunnaq, who grew up in Nanisivik, said, “I was born and raised there. It was home. Last time I went there was about two or three years ago in the summer. I just pictured all the houses that used to be there and all the other buildings that were there. All these memories from childhood came back … I miss that community.”99

Figure 4. Nanisivik townsite, 2011.

Photo by Tee Lim.

Mishak Allurut described the ever-shifting closure date and the effects this had on Arctic Bay: “Every year they said there’s only five more years left in the mine. But after five years, they said ‘oh, there’s another five.’ Then they suddenly said ‘no, we’re shutting down next year.’ So, they shut down … It spoilt the community and the people. They were expecting ‘oh, Nanisivik will last forever, so we won’t have to make savings for it,’ or plan for that loss.”

In our interviews, the people of Arctic Bay drew their own lessons from the Nanisivik experience and had many opinions regarding future mining developments in Nunavut, including impacts on wildlife and environment, infrastructure transfer, and employment.100 Mishak Allurut decried the inequity in the federal government supporting a mining company, providing infrastructure and receiving royalties, only for that infrastructure to later be destroyed and to offer little support to ensure transfer to Arctic Bay:

Knowing how the mine got started from the federal government money; infrastructure and all that was provided by the government, they helped the company to be there, to mine the land, and get royalties from it even, we were living close by, but the federal government didn’t help us like they helped Nanisivik. Even though they were a business, you know, they gave them a big swimming pool, school, rcmp, health centre, even adult education, daycare, there was a big complex there that was provided by the federal government. So the government should have focused their attention on that infrastructure, get them back to Arctic Bay, you know, rather than just demolishing them … they should have treated us the same, how they’re treating the wealthy companies up there.

He continued by calling for materials and infrastructure from existing and future projects to be transferred back to communities at closure, as opposed to being destroyed, as well as recommending that royalties be invested in a legacy fund “for the future when they close down. Either use that to train people, or to help the community get infrastructure, or support them in some way.” One Elder agreed: “When any mine closes, the closest community to the mine should receive benefit, for all the equipment and buildings, instead of demolishing them. Give them to the local people, and also money to help the community.”101

Discussion and Conclusion

In 2004, CanZinco executive Bob Carreau declared Nanisivik a success in light of its completed closure and reclamation, rather than abandonment: “Unlike many businesses where closure often means failure, closure of a mine is, in fact, a measure of success … If you didn’t do that, you would be doing abandonment, and that’s not the case with Nanisivik.”102 The sentiment recalls Steven High, Lachlan MacKinnon, and Andrew Perchard’s critique of the same “jingoistic language of entrepreneurial boosterism that is too often used with residents of former mill, mine, and factory towns as a just-so explanation for economic collapse or stagnation.”103 Carreau was correct that the mine itself was not abandoned – unlike so many others across northern Canada – yet as we have argued, the community of Arctic Bay was effectively abandoned. Tracing a clear pattern of cyclonic development, a sudden flood of capital, labour, materials, and knowledge followed Nanisivik’s rapid development in the northern Qikiqtaaluk region, at a time when Inuit had still only relatively recently moved from traditional ilagiit nunagivaktangit – camps and places used regularly or seasonally for hunting, harvesting, and gathering – to communities such as Arctic Bay.104 Within the space of 30 years, the flood had largely receded, with nearly every aspect of the project erased in the years following Nanisivik’s closure.

Earlier deindustrialization scholarship tended to focus on material industrial ruins, whereas we have focused here on wider processes of ruination, alienation, and loss.105 “Ruination” as “an act perpetrated,” following Stoler, draws our attention to sites “neither recognized as ruins nor as the ruination of colonialism; they are not acknowledged to be there at all.”106 Simply because Nanisivik has been remediated, largely erased from the landscape and rendered no longer “tangible,” the mine – as an exercise in industrial colonialism – continues to haunt the residents of Arctic Bay.

Perhaps because relatively few Inuit were employed at Nanisivik, especially in its later stages, much of this case speaks to the particular experience of Indigenous peoples on settler-colonial resource peripheries. As Dene scholar Glen Coulthard argues, Indigenous–state relations in Canada are characterized primarily by a history of dispossession – of lands and resources – and less so a drive to create proletarian labour forces.107 Colonial dispossession took particular form in the Arctic, in that it took place for the purposes of exploiting the resources under the land – minerals, oil, and gas – rather than appropriating land for settlement.108 Instating the wage relation and creating Inuit workers in the High Arctic was certainly a goal of the state at Nanisivik. But the state’s overriding agenda of assimilating Inuit and dispossessing them of their lands and resources, in order to facilitate capital accumulation by mining companies, proved a greater driver than producing Inuit labour at Nanisivik. As a consequence, for many Arctic Bay Inuit the loss of employment and direct economic benefits from mining was not the most tangible and important issue in mine closure debates and memories.

While local reactions to Nanisivik’s closure were rife with emotional narratives, few stories followed the pattern of employment and income loss so prevalent in deindustrialization scholarship. As well, in the Nanisivik case, the environmental concerns that are frequently the focus of scholarship on mining impacts did not figure as centrally as other issues in the community’s responses.109 Instead, the most notable impact was lost infrastructure, a factor much more consequential than unemployment created through downscaling or closure. More than just a “tragic waste,” the fate of Nanisivik’s transportation and townsite infrastructure became a flashpoint for community advocacy from the first announcement of the closure.110 This sense of disappointment, loss, and resentment continued to linger within Arctic Bay ten years after operations ceased and must be understood in the context of a housing crisis and infrastructure deficit that plagues Canada’s northern Indigenous communities.111 Every structure that at some point was celebrated as a contribution of the mine – “accommodations, private homes; a fully integrated school; an all-denominational church, a nursing station, an rcmp station, a fire station, post office, rec centre with a full gymnasium, swimming pool … a community in all senses of the word”112 – was bulldozed and burned, buried in the mine shaft and sealed. Compounding this injustice was the fact that $19.9 million of Nanisivik’s townsite infrastructure had been publicly funded (see Table 1).

Ruination, as Stoler asserts, is also a cause of loss.113 The lost infrastructure here also represents more than just the material; it signifies the loss of certain land/place relations, both those preceding Nanisivik and those put in place by industrial development itself. The loss of infrastructure was emblematic of a protracted sense of alienation among residents of Arctic Bay, who experienced ruination through absence as opposed to the presence of material ruins, like a derelict mill or factory – alienation from the project’s benefits, during both operations and closure, that they could and should have had as a result of the development taking place on their ancestral territories. And alienation from place, both the lost community of Nanisivik and relations with its people, resources, and infrastructure. In these ways, the forms of displacement and ruination experienced by northern Indigenous communities at the resource periphery such as Arctic Bay evidently manifest differently than do those in heartland and industrial core communities. Nevertheless, analogous to other research with former residents of mining towns in Canada, former residents of Nanisivik indicated emotional difficulties and “psychological scars” caused by the shutdown of a community that was “home,” a place where friendships and families were nurtured for over 26 years.114

The economic diversification of mining communities is a challenge that is well understood, consistently proving “difficult given the small size and remoteness of many mine settlements.”115 Small, remote, and Indigenous communities like Arctic Bay face particular challenges to achieving conventional economic diversification when nearby mines close. Even more so than heartland communities facing deindustrialization, they lack primary industry alternatives such as agriculture or forestry, or strong manufacturing or tourism prospects.116 As well, in the case of local Indigenous employees and their communities, labour mobility and new economic opportunities are far more constrained and have different implications than for workers from outside the region. As with the period of Nanisivik’s development and opening in the 1970s, the central role of Inuit land-based economic activities like hunting in sustaining communities and offering an existing, diversified regional economic base remained poorly understood and supported in the deindustrialization period following the mine’s closure in 2002.117

In spite of these experiences of deindustrialization and community decline, extractive industry continues to be proposed as the main driver of economic development in the Canadian North.118 At the signing of the Strathcona Agreement in 1974, the Polaris and Mary River mining projects were cited as economic opportunities to “take the place of Strathcona Sound.”119 However, as Green and others have shown, as a fly-in/fly-out (fifo) site the Polaris mine contributed even less to the socioeconomic development of its closest community, Resolute Bay, than Nanisivik contributed to Arctic Bay.120 The fifo model has long since replaced the establishment of mining towns such as Nanisivik but does not resolve the challenges of economic diversification at the resource periphery, and it brings with it a host of social and community impacts.121 In fact, mobility generated by the fifo model likely “increases the geographic spread of economic decline resulting from mine and mill closure.”122 As for Mary River, Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation’s contentious mine only opened in 2014, twelve years after Nanisivik had closed, and has itself seen controversy and shifting levels of extraction (and employment).123

For many in Arctic Bay and Nunavut, Nanisivik provided hard lessons in industrial development and mine closure. Nanisivik has been credited as a learning experience, edging Inuit “out of isolation into the mainstream of the Native political process.”124 The mine was developed around the time of the first Inuit land claim, as well as the formation of an emerging national association, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (itc).125 Early in the mine’s life, the itc described Nanisivik as “a monument to the colonial mentality,” arguing that it represented an infringement of Inuit property rights given the absence of a formal land claims agreement in the eastern Arctic.126 Indeed, the singular focus on industrial modernization also ran contrary to rhetoric at the project’s outset that Inuit be permitted to choose their own futures. Inuit attempts to reassert control of space and territory at this level would culminate in the signing of the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement (nlca) almost two decades later, in 1993, and the creation of Nunavut in 1999. Yet when it came to the closure and decommissioning of Nanisivik, Inuit from Arctic Bay were ultimately unable to influence mine closure outcomes according to their preferences and, indeed, demands. This despite closure taking place after the largest of the Indigenous land claims and self-determination agreements entered into by Canada.127 If the debate over deindustrialization is “fundamentally about ‘who is going to control the future,’” as Steven High suggests, it does not appear that Inuit in Arctic Bay were yet able to assert control of their own post-mining future.128

The Nanisivik experience is also revealing in terms of the persistent absence of regulatory responsibility for closure and deindustrialization outcomes, especially social and economic ones.129 At Nanisivik, no party was willing to override economic and liability disincentives and assume responsibility for ensuring the redistribution of resources important to the community. The situation was exacerbated by the complete failure of the nirb, the regulatory agency created by the nlca, to ensure that socioeconomic considerations were addressed during the closure process. Having observed the lessons from Nanisivik, and not wanting communities “left high and dry” like Arctic Bay, the Kivalliq Inuit Association’s Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement (iiba) with Cumberland Resources Ltd. for the Meadowbank gold mine enshrined the right of first refusal in the purchase of the mine’s assets after closure.130 The iiba also specifies that Cumberland prepare and fund a “post-closure Inuit wellness strategy.”131 As is typical of these agreements, its details are confidential. It appears that neither the strategy nor the iiba in general prepared the affected community of Baker Lake for Meadowbank’s initial projected closure in 2017; the Hamlet of Baker Lake declared that the closure will “have a devastating effect on the community both socially and economically as the community goes to 80 per cent unemployment.”132 A community-based closure planning study by Annabel Rixen and Sylvie Blangy concluded that in Baker Lake, “mining has failed to produce lasting ‘social and economic development’ when we consider its holistic impacts on well-being and subsistence lifestyles.”133 Aligning with Mishak Allurut’s suggestion of legacy funds, in 2016 the Qikiqtani Inuit Association established a fund supported by revenues from its Baffinland iiba and other sources, intended to “save for future generations of Inuit while providing benefits to current generations.”134

Ultimately, the experience of deindustrialization and ruination at Nanisivik echoes many of the same historical and contemporary debates about the connections between industrial development and settler colonialism on Canada’s resource periphery. This article explored the intimate local dynamics of these processes and the deep feelings of loss and resentment that continue to haunt the social memory of Arctic Bay residents. More than merely material impacts and economic dislocation typically associated with closure, we argue, Tununirusirmiut experienced mine closure in the context of ruinous policies of industrial colonialism that promised much but left few positive legacies for the community. As Nunavummiut weigh the prospects of future rounds of mineral development and deindustrialization in which they are more deeply implicated, it is urgent to consider the full range of mine closure’s impacts on and implications for local communities.

The authors wish to thank the community of Ikpiarjuk/Arctic Bay, and interpreter Mishak Allurut in particular. We also thank Dr. Frank Tester for his role in this work. This research was funded in part by grants from ArcticNet, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Western Mining Action Network/Indigenous Environmental Network. These funders had no direct involvement in the research itself. This research was approved under ubc Behavioural Research Ethics Board certificates H10-02539 Industrial Development at Arctic Bay and H10-01503 Adaptation, Industrial Development and Arctic Communities: Experiences of Environmental and Social Change. Nunavut Research Institute license # 03 054 11R-M-Amended, Adaptation, Industrial Development and Arctic Communities: Experiences of Environmental and Social Change.

1. Mishak Allurut, “Nanisivik Had a Permanent Impact on Nunavut,” Nunatsiaq News, 20 September 2002, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/nanisivik_had_a_permanent_impact_on_nunavut/.

2. Koonoo Oyukuluk, Arctic Bay Elder and hunter, interview in Inuktitut by Tee Lim and interpreter Mishak Allurut, August 2011.

3. The road was no longer maintained by the Government of Nunavut as of 2011.

4. “There appears to be considerable merit in the idea of considering the Strathcona Sound project as a controlled experiment in Arctic development.” J. P. Drolet, assistant deputy minister (Mineral Development), Energy, Mines and Resources (emr), memorandum to the Minister. “Notes on the Proposed Development of a Zinc-Lead Deposit on Strathcona Sound, Northern Baffin Island,” 21 November 1973, rg 21, vol. 2, file 1.50.15.3, disc A2010-00477-Release – Strathcona Sound, Nanisivik Mine, File A201000487_2011-02-07_13-02-29, pp. 892–897, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter lac).

5. Arn Keeling and John Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities in Northern Canada: History, Politics, and Memory (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2015).

6. Trevor Barnes, “Borderline Communities: Canadian Single Industry Towns, Staples, and Harold Innis,” in Henk Van Houtum, Olivier Kramsch, and Wolfgang Zierhofer, eds., B/ordering Space (Burlington: Ashgate, 2005), 109–122; Thierry Rodon, Arn Keeling, and Jean-Sébastien Boutet, “Schefferville Revisited: The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of Iron Mining in Québec-Labrador,” Extractive Industries and Society 12 (2022): Art. 101008.

7. See, for example, Marietjie Ackermann, Doret Botha, and Gerrit van der Waldt, “Potential Socio-economic Consequences of Mine Closure,” Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 14, 1 (2018): Art. a458; J. Stacey, A. Naude, M. Hermanus, and P. Frankel, “The Socio-economic Aspects of Mine Closure and Sustainable Development: Literature Overview and Lessons for the Socio-economic Aspects of Closure - Report 1,” Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 110, 7 (July 2010): 379–394; William R. Freudenburg, “Addictive Economies: Extractive Industries and Vulnerable Localities in a Changing World Economy,” Rural Sociology 57, 3 (1992): 305–332; André Xavier, Marcello Veiga, and Dirk van Zyl, “Introduction and Assessment of a Socio-economic Mine Closure Framework,” Journal of Management and Sustainability 5, 1 (2015): 38–49.

8. Steven High, “‘The Wounds of Class’: A Historiographical Reflection on the Study of Deindustrialization, 1973–2013,” History Compass 11, 11 (2013): 994–1007.

9. See Rosemary Power, “‘After the Black Gold’: A View of Mining Heritage from Coalfield Areas in Britain,” Folklore 119, 2 (August 2008): 160–181; David Robertson, Hard as the Rock Itself: Place and Identity in the American Mining Town (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2006); Tim Strangleman, “Networks, Place and Identities in Post-industrial Mining Communities,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25, 2 (2001): 253–267.

10. Jim Phillips, “The Moral Economy of Deindustrialization in Post-1945 Scotland,” in Steven High, Lachlan MacKinnon, and Andrew Perchard, eds., The Deindustrialized World: Confronting Ruination in Postindustrial Places (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2017), 315.

11. Sherry Lee Linkon, “The Half-Life of Deindustrialisation: Twenty-First Century Narratives of Work, Place and Identity” (paper presented at Deindustrialization and Its Aftermath: Class, Culture and Resistance, Montréal, May 2014), 2, cited in Tim Strangleman, “Deindustrialisation and the Historical Sociological Imagination: Making Sense of Work and Industrial Change,” Sociology 51, 2 (2017): 475.

12. Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh and Rebecca Lawrence, “Mine Closure and the Aboriginal Estate,” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2019, 1 (2019): 66.

13. Steven High, “Introduction,” in “The Politics and Memory of Deindustrialization in Canada,” special issue, Urban History Review 35, 2 (2007): 2–13; Trevor Barnes, Roger Hayter, and Elizabeth Hay, “Stormy Weather: Cyclones, Harold Innis, and Port Alberni, BC,” Environment and Planning A 33, 12 (2001): 2127–2147; Roger Hayter and Trevor Barnes, “Canada’s Resource Economy,” Canadian Geographer 45, 1 (2001): 36–41; Roger Hayter, Trevor Barnes, and Michael Bradshaw, “Relocating Resource Peripheries to the Core of Economic Geography’s Theorizing: Rationale and Agenda,” Area 35, 1 (2003): 15–23.

14. Barnes, “Borderline Communities”; Barnes, Hayter, and Hay, “Stormy Weather”; Arn Keeling, “‘Born in an Atomic Test Tube’: Landscapes of Cyclonic Development at Uranium City, Saskatchewan,” Canadian Geographer 54, 2 (2010): 228–252; Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities, 6.

15. R. A. Clapp, “The Resource Cycle in Forestry and Fishing,” Canadian Geographer 42, 2 (1998): 129–144; Keeling, “Atomic Test Tube.”

16. Keeling, “Atomic Test Tube,” 230.

17. Hayter, Barnes, and Bradshaw, “Relocating Resource Peripheries.”

18. Corey Snelgrove, Rita Dhamoon and Jeff Corntassel, “Unsettling Settler Colonialism: The Discourse and Politics of Settlers, and Solidarity with Indigenous Nations,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3, 2 (2014): 1–32, 8; Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, 4 (2006): 387–409; Cole Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94, 1 (2004): 165–182.

19. Glen Coulthard, “From Wards of the State to Subjects of Recognition? Marx, Indigenous Peoples, and the Politics of Dispossession in Denendeh,” in Audra Simpson and Andrea Smith, eds., Theorizing Native Studies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 56–98; Dawn Hoogeveen, “Sub-surface Property, Free-Entry Mineral Staking and Settler Colonialism in Canada,” Antipode 47, 1 (2015): 121–138; Kyle Whyte, “Indigenous Experience, Environmental Justice and Settler Colonialism,” ssrn Electronic Journal 3, 1 (2016), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2770058; Anna J. Willow, “Indigenous Extractivism in Boreal Canada: Colonial Legacies, Contemporary Struggles and Sovereign Futures,” Humanities 5, 3 (2016): 55.

20. Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities. On mining town–First Nation relations and histories, see also Leslie Robertson, Imagining Difference: Legend, Curse and Spectacle in a Canadian Mining Town (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2005); Fred Burrill, “The Settler Order Framework: Rethinking Canadian Working-Class History,” Labour/Le Travail 83 (2019): 173–197.

21. Steven High, “The Rise and Fall of Mill Colonialism in Northern Ontario,” in High, MacKinnon, and Perchard, eds., Deindustrialized World, 258.

22. Ann Laura Stoler, ed., Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 195. Stoler’s conceptualization of “ruination” has been influential on and widely used in the deindustrialization literature (see High, MacKinnon and Perchard, eds., Deindustrialized World). The full quote reads, “Imperial projects are themselves processes of ongoing ruination, processes that ‘bring ruin upon,’ exerting material and social force in the present. By definition ruination is an ambiguous term; both an act of ruining, a condition of being ruined, and a cause of it. Ruination is an act perpetrated, a condition to which one is subject, and a cause of loss. These three senses may overlap in effect but they are not the same. Each has its own temporality. Each identifies different durations and moments of exposure to a range of violences and degradations that may be immediate or delayed, subcutaneous or visible, prolonged or instant, diffuse or direct.”

23. High, “Rise and Fall.”

24. Warren Bernauer, “The Limits to Extraction: Mining and Colonialism in Nunavut,” Canadian Journal of Development Studies 40, 3 (2019): 404–422; Jean-Sébastien Boutet, “Opening Ungava to Industry: A Decentring Approach to Indigenous History in Subarctic Québec, 1937–54,” Cultural Geographies 21, 1 (2014): 79–97; Ken Coates, “The History and Historiography of Natural Resource Development in the Arctic: The State of the Literature,” in Chris Southcott, Frances Abele, David Natcher, and Brenda Parlee, eds., Resources and Sustainable Development in the Arctic (London: Routledge, 2018), 23–41; Ginger Gibson and Jason Klinck, “Canada’s Resilient North: The Impact of Mining on Aboriginal Communities,” Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health 3, 1 (2005): 116–139; Rebecca Hall, “Diamond Mining in Canada’s Northwest Territories: A Colonial Continuity,” Antipode 45, 2 (2013): 376–393; Arn Keeling, “Atomic Test Tube”; Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities; Emma LeClerc and Arn Keeling, “From Cutlines to Traplines: Post-industrial Land Use at the Pine Point Mine,” Extractive Industries and Society 2, 1 (2015): 7–18; Liza Piper, The Industrial Transformation of Subarctic Canada (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2009); Thierry Rodon and Francis Lévesque, “Understanding the Social and Economic Impacts of Mining Development in Inuit Communities: Experiences with Past and Present Mines in Inuit Nunangat,” Northern Review 41 (2015): 13–39; John Sandlos and Arn Keeling, “Claiming the New North: Development and Colonialism at the Pine Point Mine, Northwest Territories, Canada,” Environment and History 18, 1 (2012): 5–34; Sandlos and Keeling, “Toxic Legacies, Slow Violence, and Environmental Injustice at Giant Mine, Northwest Territories,” Northern Review, no. 42 (2016): 7–21.

25. Keeling and Sandlos, eds., introduction to Mining and Communities, 7; Arn Keeling and John Sandlos, “Environmental Justice Goes Underground? Historical Notes from Canada’s Northern Mining Frontier,” Environmental Justice 2, 3 (2009): 117–125.

26. Arn Keeling and John Sandlios, “Ghost Towns and Zombie Mines: The Historical Dimensions of Mine Abandonment, Reclamation, and Redevelopment in the Canadian North,” in Stephen Bocking and Brad Martin, eds., Ice Blink: Navigating Northern Environmental History (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2017), 377–420; Anne Dance, “Northern Reclamation in Canada: Contemporary Policy and Practice for New and Legacy Mines,” Northern Review 41 (2015): 41–80.

27. Heather Green, “‘There Is No Memory of It Here’: Closure and Memory of the Polaris Mine in Resolute Bay, 1973–2021,” in Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities, 330.

28. On Indigenous environmental justice, see Whyte, “Indigenous Experience”; Deborah McGregor, Steven Whitaker, and Mahisha Sritharan, “Indigenous Environmental Justice and Sustainability,” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43 (2020): 35–40; McGregor, “Mino-Mnaamodzawin: Achieving Indigenous Environmental Justice in Canada,” Environment and Society 9, 1 (2018): 7–24.

29. Tara Cater and Arn Keeling, “‘That’s Where Our Future Came From’: Mining, Landscape, and Memory in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut,” Études/Inuit/Studies 37, 2 (2013): 59–82.

30. Robert B. Gibson, The Strathcona Sound Mining Project: A Case Study in Decision Making (Ottawa: Science Council of Canada, 1978), 247.

31. Statistics Canada, “Arctic Bay, Nunavut” Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population, Statistics Canada – Catalogue No. 98-316-X2021001, released 9 February 2022, accessed 26 October 2022, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

32. John Q. Adams, “Settlements of the Northeastern Canadian Arctic,” Geographical Review 31, 1 (1941): 112–126.

33. Statistics Canada, “2006 Profile of Aboriginal Children, Youth and Adults: Arctic Bay, Nunavut,” Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2006, updated 31 October 2011, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/89-635/P4.cfm?Lang=eng&age=3&ident_id=1&B1=0&geocode1=081&geocode2=083.

34. Mishak Allurut, personal communication with Tee Lim, 30 September 2011.

35. Scott Midgley, “Contesting Closure: Science, Politics, and Community Responses to Closing the Nanisivik Mine, Nunavut,” in Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities, 293–314; Rodon and Lévesque, “Social and Economic Impacts.”

36. Neil R. Burns and Michael Doggett, “Nanisivik Mine – A Profitability Comparison of Actual Mining to the Expectations of the Feasibility Study,” Exploration and Mining Geology 13, 1–4 (2004): 119–128; Green, “There Is No Memory”; Robert McPherson, New Owners in Their Own Land: Minerals and Inuit Land Claims (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2003); Rodon and Lévesque, “Social and Economic Impacts.”

37. Nanisivik Mines Ltd. was formed to develop the lead-zinc deposits. Strathcona Mineral Services Ltd. served as the project manager during this initial period. mri retained majority ownership of Nanisivik until 1989, when it was purchased by Conwest Exploration Ltd. Breakwater Resources Ltd. purchased the mine in 1996, creating CanZinco Ltd. to operate the mine, and maintained ownership throughout the reclamation and closure period up until Breakwater’s acquisition by Nyrstar in 2011.

38. “Specifically, the company and the government have accepted a goal to fill 60 per cent of the work force with Inuit in three years from the start of production.” Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (diand), “Speech Notes for the Honourable Jean Chrétien, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, at the Signing of the Nanisivik Mines Ltd. Agreement. Communiqué,” 18 June 1974, and “Speech Notes for the Honourable Jean Chrétien, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development at the Legislative Dinner on the Occasion of the Opening of the 51st Session of the Council of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife,” 18 January 1974, both in rg 21, vol. 5, file 1.50.15.3, disc A2010-00477-Release – Strathcona Sound, Nanisivik Mine, file A201000477_2011-01-05_11-26-17, lac.

39. Burns and Doggett, “Nanisivik Mine.”

40. A utilidor is an above-ground insulated conduit used for general utility service, common in arctic climates.

41. Gartner Lee Limited, “Nanisivik Mine 2002 Closure and Reclamation Plan. Volume 1” (Vancouver: CanZinco Ltd., February 2002); CanZinco Ltd., “Nanisivik Mine 2004 Reclamation and Closure Plan” (Vancouver: CanZinco Ltd., 2004); Consilium Nunavut Inc., “Alternative Use Options for the Nanisivik Mine Facilities: Final Report” (Iqaluit: Consilium Nunavut Inc., 2002).

42. McPherson, New Owners; Cater and Keeling, “‘That’s Where Our Future Came From’”; Frank James Tester, Drummond E. J. Lambert, and Tee Wern Lim, “Wistful Thinking: Making Inuit Labour and the Nanisivik Mine Near Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay), Northern Baffin Island,” Études/Inuit/Studies 37, 2 (2013): 15–36.

43. R. B. Gibson, Strathcona Sound Mining Project, 100.

44. In fact, the government (and Inuit) already had painful experience of such transitions, with the rapid development and closure of the Rankin Inlet mine in the Keewatin (Kivalliq) region. See Arn Keeling and Patricia Boulter, “From Igloo to Mine Shaft: Inuit Labour and Memory at the Rankin Inlet Nickel Mine,” in Keeling and Sandlos, eds., Mining and Communities, 35–58.

45. Doug Brubacher, “The Nanisivik Legacy in Arctic Bay: A Socio-economic Impact Study,” Brubacher and Associates, Ottawa, 2002.

46. Jim Marshall, quoted in Philip Lauritzen, “Canadian Mine – Arctic Resources Policy: Marmorilik’s Opposite Neighbour Stakes on Eskimos,” Information [Danish periodical], 8 December, 1977, rg 21, vol. 8, file 1.50.15.3,, 2, lac. For further discussion of the 60 per cent target, see Tester, Lambert, and Lim, “Wistful Thinking”; Tee Wern Lim, “Inuit Encounters with Colonial Capital: Nanisivik – Canada’s First High Arctic Mine,” MA thesis, University of British Columbia, 2013.

47. J. S. Ross, “Memorandum from J. S. Ross, Acting Head, Northern and Regional Development Section, to Jean-Paul Drolet, Assistant Deputy Minister (Mineral Development), emr, ‘Memorandum to the Cabinet, Strathcona Sound Project – Submitted by Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 8 March, 1974,’” rg 21, vol. 3, file 1.50.15.3., lac.

48. Brubacher, “Nanisivik Legacy in Arctic Bay,” 30.

49. Léa-Marie Bowes-Lyon, “Comparison of the Socio-economic Impacts of the Nanisivik and Polaris Mines: A Sustainable Development Case Study,” MSc thesis, University of Alberta, 2006; Brubacher, “Nanisivik Legacy in Arctic Bay.”

50. Bowes-Lyon, “Comparison,” 392.

51. Jim Marshall, quoted in Lauritzen, “Canadian Mine.”

52. Arctic Bay resident and former Nanisivik hospitality and custodial worker, interview by Tee Lim, September 2011. Participant requested to remain anonymous.

53. Mishak Allurut, interview by Tee Lim, August 2011. Subsequent quotations attributed to Allurut are taken from this interview.

54. Bowes-Lyon, “Comparison.”

55. Baffin Regional Inuit Association, Socio-economic Impacts of the Nanisivik Mine on Northern Baffin Region Communities (Ottawa: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1979).

56. Tester, Lambert, and Lim, “Wistful Thinking.” On “resistance” here, see, for example, Peter Kulchyski, “Primitive Subversions: Totalization and Resistance in Native Canadian Politics,” Cultural Critique 21 (1992): 171–195.