Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Article

Importing the Clairtone Sound: Political Economy, Regionalism, and Deindustrialization in Pictou County

Abstract: Following the industrial crisis of the 1920s and the Great Depression in the 1930s, consecutive provincial governments in Nova Scotia turned their efforts toward state-led economic development. After the election of Robert Stanfield and the Tories in 1956, a wholesale industrial planning model was unveiled. Indeed, Stanfieldian economic policy in Nova Scotia was predicated upon the belief that direct state-led interventionism was necessary to offset regional inequity. State corporate entities, such as Industrial Estates Limited, and renewed interest in a state-driven industrial relations paradigm were central in the province’s efforts to revitalize its flagging economy and offset predicted decline in the Cape Breton coal and steel industries. This article examines the fate of the Clairtone Sound Corporation, one of Nova Scotia’s “new industries” that emerged out of these state-led development efforts. A case study of this Stellarton-based firm reveals how structural processes of deindustrialization produced crisis even within sectors that were completely distinct from the province’s cornerstone industries of coal and steel. This case includes a reflection on the class composition of the modernist state in Nova Scotia and represents a convergence of the historiographical focus on state-led industrial development in the Maritimes and recent literature found within deindustrialization studies.

Keywords: deindustrialization, Atlantic Canada, industrial development, regionalism, Nova Scotia, electronics, coal, economic planning

Résumé : À la suite de la crise industrielle des années 1920 et de la Grande Dépression des années 1930, les gouvernements provinciaux successifs de la Nouvelle-Écosse ont orienté leurs efforts vers un développement économique dirigé par l›État. Après l›élection de Robert Stanfield et des conservateurs en 1956, un modèle de planification industrielle en gros a été dévoilé. En effet, la politique économique « stanfieldienne » en Nouvelle-Écosse reposait sur la conviction que l›interventionnisme direct dirigé par l›État était nécessaire pour compenser les inégalités régionales. Les sociétés d›État, comme Industrial Estates Limited, et le regain d›intérêt pour un paradigme de relations industrielles dirigé par l›État ont joué un rôle central dans les efforts de la province pour revitaliser son économie chancelante et compenser le déclin prévu des industries du charbon et de l›acier du Cap-Breton. Cet article examine le sort de la Clairtone Sound Corporation, l›une des « nouvelles industries » de la Nouvelle-Écosse qui a émergé de ces efforts de développement menés par l›État. Une étude de cas de cette entreprise basée à Stellarton révèle comment les processus structurels de désindustrialisation ont produit une crise même dans des secteurs complètement distincts des industries phares du charbon et de l›acier de la province. Ce cas comprend une réflexion sur la composition de classe de l›État moderniste en Nouvelle-Écosse et représente une convergence de l›accent historiographique sur le développement industriel dirigé par l›État dans les Maritimes et de la documentation récente trouvée dans les études sur la désindustrialisation.

Mots clefs : désindustrialisation, Canada atlantique, développement industriel, régionalisme, Nouvelle-Écosse, produits électroniques, charbon, planification économique

“Hi-Fi Firm Moves to Province,” declared the bold headline in the Halifax Chronicle Herald on 19 November 1964. The company, Clairtone Sound Corporation, had announced plans to open a “futuristic” production plant in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, where it would produce the electronics and chassis for a high-end line of stereos.1 Clairtone was enticed to the province through the machinations of Industrial Estates Limited (iel), a provincial Crown corporation established in 1957 by the Progressive Conservative (pc) government of Robert Stanfield to attract secondary manufacturing through the provision of financial inducement and other favourable terms. The firm’s opening was a boon for the county, which had been impacted simultaneously by the longer-term decline of the provincial coal industry and a tragic series of coal mining accidents throughout the province, including in Stellarton and in nearby Springhill.2

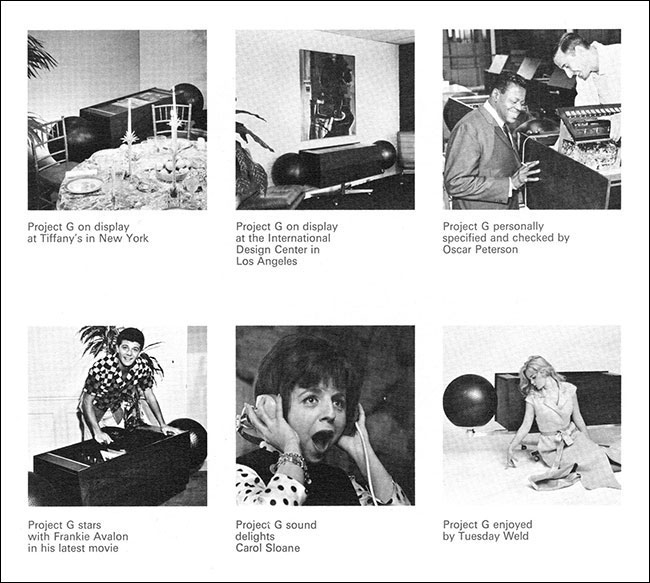

For the Stanfield administration, Clairtone was a shining example of a possible industrial future based on the development of light industry and supported by the combination of provincial subsidy and external capital. In terms of corporate image, the firm was a stark departure from the province’s cornerstone industries of coal and steel. Newspapers and glossy trade magazines printed advertisements for the company through the early 1960s, its wares were shopped in showrooms across North America, and celebrity endorsements from the likes of Oscar Petersen and Frank Sinatra lent Clairtone an air of sophistication and glamour.3

Although Clairtone only operated in Nova Scotia for a brief time, collapsing into bankruptcy in 1971, its history reveals much about how the industrial and economic development policies of the mid-20th century were deeply rooted in the political economy of the postwar period, technocratic class assumptions, and the permeable boundary between Crown corporations and private enterprise. Using Clairtone as a case study to further examine these themes, this article contributes to a broader discussion about the transformation of Canadian capitalism in the aftermath of World War II and reveals how these changes were reflected across Atlantic Canada.

“Clairtone Sound 1964 Annual Report,” mg 3 vol. 2218, file 2, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax. Reproduced by permission from Nova Scotia Archives.

In Nova Scotia, a province facing the prospect of deindustrialization and industrial closure in coal and steel, Clairtone was only one of many private beneficiaries of a far-reaching set of interventionist policy measures that were enacted to address the problem of regional underdevelopment. A close analysis of the class dimensions of industrial planning in Nova Scotia helps to expose the assumptions that politicians and capitalists made in those years. Such an approach bridges the dichotomy of intentionality and consequence, tracing the various impacts of these schemes on residents, employees in secondary manufacturing, and those who remained working in the province’s primary sectors during an age of crisis. Positioning Clairtone’s failure against the ever-present backdrop of deindustrialization reveals how the best-laid plans failed to challenge the prevailing industrial decline experienced in Nova Scotia during the 20th century.

This article suggests a partial answer to the question that Fred Burrill posed in the pages of Acadiensis in 2019: “What was the particular balance of class forces … that made these [mid-20th-century] modernizers so fervently pursue such obviously flawed industrial development schemes?”4 Tracing the intellectual and political history of interventionist industrial development in Nova Scotia, the establishment and failure of the Clairtone Sound Corporation reveals how this so-called new industry of Nova Scotia came to collapse under the dual weight of structural deindustrialization and the hubris of a political class that was committed to allowing regional and national capitalists to direct industrial development decisions and policies. Its history reflects the continuation of the slow violence of deindustrialization and, eventually, workplace closure across sectors. The contrasts between the experiences of deindustrialization in Nova Scotia’s “new industries” and the intentions of the white-collar politicians, planners, business leaders, and bureaucrats who oversaw these processes is made visible. This represents a convergence of the historiographical focus on state-led industrial development in the Maritimes and recent literature found within deindustrialization studies that more explicitly outlines experiences of industrial decline and closure.5 The great irony of this history is that Clairtone, intended to chart a new frontier for the provincial economy, began its collapse at exactly the same time that the coal and steel industries of Cape Breton were facing their own crises, in 1966 and 1967.

The political economy of Canada in the immediate aftermath of World War II helps to explain some of the appetite for state-led development in Nova Scotia during the 1950s. The economic crisis of the 1930s, the wartime continentalization of the North American economy, and the slow Canadian withdrawal from British imperial ties in favour of American big business created an environment where the laissez-faire liberalism of Canada’s entrenched business elites found itself in the political wilderness. The impact on the Maritimes was significant; E. R. Forbes describes how the wartime economy was operated as a centralized manufacturing hub, setting the stage for postwar growth in Ontario and Québec and calcification in Halifax and Saint John.6 Emerging from these circumstances, the increasing popularity of state planning and development measures was an ideological transformation within Canadian capitalism and among its elite operators. Don Nerbas describes C. D. Howe as symbolic of this shift, in that he “introduced a managerial outlook to government and … helped forge a new relationship between the state and the private sector.”7 While the residual ideological liberalism within Canadian big business worked to challenge Howe politically during the 1930s and 1940s, the policies of the Stanfield government in Nova Scotia after 1956 suggests that this transition also took root at the provincial level.8

Part of the reason why Stanfield took up the mantle of managerial capitalism during the 1950s was to distinguish himself from his chief political rival, the long-serving Liberal premier Angus L. Macdonald. Under his purview, infrastructure was an essential aspect of provincial development. Between 1933 and 1939, the Macdonald Liberals arranged for the paving of nearly 1,300 kilometres of Nova Scotia roads.9 Likewise, the Halifax bridge (1954) and the Canso Causeway (1955) were both beneficiaries of Macdonald’s “infrastructure liberalism.”10 Despite this, Macdonald remained deeply committed to a provincial economy based on private equity and eschewed direct relief during the Depression years, favouring a public works approach.11 The Jones Report on Nova Scotia’s Economic Welfare within Confederation, commissioned by Macdonald soon after he was first elected premier in 1933, articulated this ideological vision in respect to the province’s basic industries. On coal and steel, the report sang the praises of free trade and rejected government intervention in the markets.12 That these industries would be nationalized just over 30 years later reflects the speed with which the intellectual and policy landscape shifted under the feet of provincial elites.

As Nerbas’ work reminds us, the transitory phase within Canadian capitalism is not so neat as to fall clearly between two dichotomous forms – with Macdonald representing the liberal tradition and Stanfield taking up the mantle of managerial interventionist capitalism. In 1951, two years before Stanfield would challenge Macdonald with an election platform based on regional economic development and provincial industrial growth, some Nova Scotia politicians were already implementing economic development designs. The municipal government in the city of Halifax created its own industrial development committee and met several times through the fall of 1951 to discuss the possibility of incentivizing various industrial employers to relocate to the city. This included grading and readying city property for sale to potential newcomers and establishing tax reductions and incentives for interested firms.13 The provincial government contributed to these efforts. R. D. Howland, the Deputy Minister of Trade and Industry, travelled to London that same year to try to entice several British firms to relocate to Halifax.14 In 1954, following Macdonald’s unexpected death and the successive Liberal premierships of Harold Connolly and Henry Hicks, the Nova Scotia government worked closely with the Maritime Board of Trade to establish the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council (apec) and move toward a concerted regional development model.15

There is also a regionalist dimension to the willingness of the Stanfield regime to employ increasingly interventionist measures – from the provision of subsidies through iel to attract firms like Clairtone, up to and including the eventual nationalization of the Cape Breton steel industry in 1967.16 The dominant political strand of the regionalist impulse, which held significant influence within the provincial conservative tradition, emerged from the Maritime Rights movement of the 1920s.17 As Forbes describes, this movement was grounded in long-standing “aspirations of a political, economic, social, and cultural nature which were seriously threatened by the relative decline of the Maritime provinces” during the first decades of the 20th century.18 The purveyors of this mode of regionalism were largely concerned with the old inequities of Confederation, highlighted by the lack of regional political representation, the railway tariff policy, and the threat to regional businesses posed by increasing centralization of the Canadian national economy.19 Despite its broad rhetoric, David Frank suggests that the Maritime Rights movement relied upon a relatively narrow base of support, largely drawing on the region’s businessmen and professional classes.20 Steeped in this nexus of Halifax–Saint John political regionalism, the program of industrial development enacted under Stanfield sought to diminish some of the economic difficulties facing the Maritimes under Confederation; however, as we shall see, such efforts were not rooted in the aims of social justice and were ultimately devoid of significant social democratic commitment.

By way of contrast, a more class-conscious form of regionalism had also percolated within the coalfields of Nova Scotia – from Pictou County northward to Cape Breton Island – since the storied “labour wars” of the 1920s. Coal miners across the province were instrumental in building working-class solidarity and a regional labour movement. This included the foundation of the Maritime Labor Herald newspaper, a robust trade union tradition, a serious effort to elect labour politicians municipally and provincially, and a highly politicized understanding of regional disparity under Canadian capitalism rooted in notions of class conflict.21 Based on these understandings, Nova Scotia workers frequently expressed their own desire for state-led interventionism – one rooted in working-class solidarity and economic justice.

With the 1947 report by the royal commission investigating the coal industry, known as the Carroll Commission, it was clear that members of District 26 of the United Mineworkers of America (umwa) were concerned about the possibility of deindustrialization in the province. In a 1945 brief to the committee, the union expressed a desire to see state subsidization for the coal industry – but also called for attention to the building of safe, healthy communities through employment standards, social amenities, and the possibility of educational attainment.22 The miners were disappointed with the findings of the report; it included the continuation of pre-war transportation subventions and subsidies but expressed the desire to return to free enterprise quickly, with the planned relaxation of various other wartime mining subsidies.23 Clarie Gillis, Co-operative Commonwealth Federation representative from Cape Breton South, argued in Parliament that a concerted state-led effort to rehabilitate the province’s coal mining industry remained necessary for the sector to regain competitiveness and to ensure that mining communities were not left out in the cold in the face of possible industrial closure.24 During the 1947 coal strike in Pictou County and Cape Breton, coal miners directly called for state subsidy and the implementation of a more equitable relationship wherein workers could have more influence over the direction of their industry.25

When state intervention became the modus operandi of both levels of government during the 1950s, it was never intended as the sort of social partnership that the Nova Scotia miners had continually proposed. Rather, this growth model was predicated on the combined largesse of the modernist provincial state and the desires and direct participation of regional capitalists and the business class. The composition of the Nova Scotia delegation on the initial apec planning program makes this clear, as it included several provincial business owners and managers like Lionel Forsyth, president of Dosco.26 The class dimensions of these shifts were obvious; the combination of government planning and industrial development in Nova Scotia would not proceed as a partnership between state and worker, as the Cape Breton miners and steelworkers had called for in the 1940s. Rather, proponents of the new paradigm viewed it as a natural collaboration between capital and provincial politicos and powerbrokers. This would result in a system wherein provincial business owners and financiers would have significant control over provincial spending in the realm of development, with little direct political oversight. Nowhere is this more evident than in the rise and fall of Clairtone Sound.

A Blank Slate: Clairtone Sound and Deindustrializing Pictou County

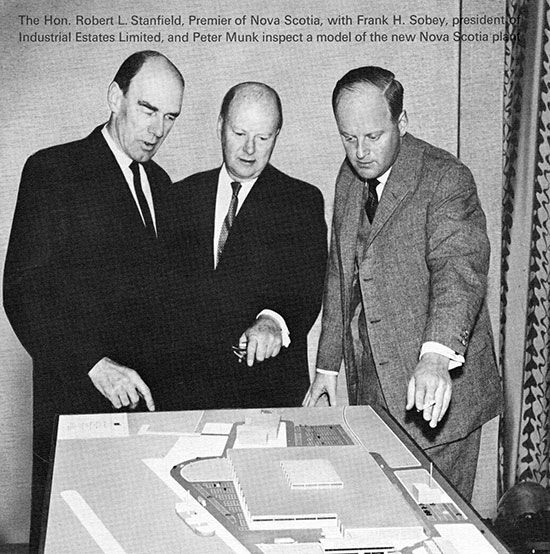

If there was a central notion that characterized Stanfield’s program of industrial development, it was that it was the responsibility and the duty of the provincial government to create appropriate conditions by which firms from outside the region could be enticed to enter and remain in Nova Scotia. Provincial corporations and government policies would help to establish business incubators that would produce economic growth and employment. A class-based “meritocratic ideal” informed these efforts from the outset. Grocery magnate, multimillionaire, and regional capitalist Frank Sobey was named as the president of iel upon its establishment. Harkening back to C. D. Howe’s “dollar-a-year men,” Sobey collected only one dollar in annual remuneration in this role – ostensibly a “selfless and tireless” act, albeit one that would place him at the very centre of economic development in the province for nearly thirteen years.27 There was also a transnational dimension to this undertaking; indeed, iel was predicated upon the earlier Industrial Trading Estates that had been established in Britain in the immediate aftermath of World War II and involved a host of elite figures throughout British business and politics.28

The importation and implementation of these programs, however, were combined with Stanfield’s understanding of Nova Scotia’s place within Canada. At the first meeting of the iel board of directors, he expressed the view that the corporation had been created to “encourage the promotion, expansion, diversification and development of industrial activity in Nova Scotia.”29 The role of the state, in this view, was to offset the structural limitations facing the Maritimes under Confederation and nurture an environment that would appeal to the import of extraregional capital. Stanfield took the seeds of the development policies that had been established throughout Europe, planted them in the fertile soil of a provincial political mosaic steeped in one view of economic regionalism, and nurtured them with the knowledge of a growing capitalist class unaware of its own limitations. The water of life, in this metaphor, was the loans, real estate deals, and other forms of subsidy that could be provided through provincial largesse.30 In the case of Clairtone, iel would come to play an even more significant role – eventually assuming direct ownership of the firm.

Of course, iel was not initially designed to purchase shares, let alone to directly own and operate businesses within the province. Nor was it designed explicitly for the purposes of mitigating or offsetting deindustrialization. The new Crown corporation, however, could not escape the material conditions of the provincial economy. Coal and steel were both on shaky ground by the end of the 1950s, a situation that harkened a cloudy horizon in a province where approximately 20 per cent of the working population relied to some extent on those industries. But it was not a slow process of decline that would force the interventionist state to begin grappling with deindustrialization; instead, its hand was forced on 23 October 1958, when disaster struck the Dominion No. 2 Colliery at Springhill.

When the “bump” – an underground seismic event – shook the mine, collapsing sections, killing 75 men, and trapping many others underground for days while they awaited rescue, it was clear that the colliery was unlikely to reopen. A major media event, the rescue efforts played out across national newspapers and television screens as Canadians watched a mine disaster unfold. Stanfield recognized an opportunity for the new firm to spring into action; he requested that the economic response to Springhill be given top priority and noted that a new development corporation would be formed to “separate the industrial from the other aspects of the problem arising from the closure of the coal mines there.”31 As a result, the Springhill Development Corporation was created as a subsidiary of iel. Acting as requested, the directors entertained submissions for various developments – from wood products to battery storage to pump and brassiere manufacturers.32 These negotiations appear to have taken the shape of private conversations between various members of the board or president Frank Sobey and interested industrialists. Nowhere were the economic concerns of Springhill residents, let alone displaced coal miners or their union, considered. This was the class dimension inherent within “separat[ing] the industrial from the other aspects” of deindustrializing Springhill.33 It would be an early precursor to how industrial development would unfold tout court.34

The divorce of economic development from local context that was exhibited after the Springhill mine closure reveals something about how the provincial government and the iel board of directors viewed their role. The decline of coal and steel created an opportunity to remake Nova Scotia into a secondary manufacturing hub that could provide a release valve to the dawning industrial crisis. The province, in this view, was a blank slate – simply awaiting the right handshake (or series of handshakes) that would solidify the necessary deals to drag the old industrial hinterland into the modern era. It is a mistake to view this as indicative of a progressive or social democratic approach to governance under the pcs, as do several Stanfield biographers.35 Rather, this vision was based on Stanfield’s nearly unlimited trust in the provincial industrialists to apply their business acumen in ways that would supposedly mutually benefit investors, developers, workers, and the province. The composition of iel executives reflects this view. Sobey, the supermarket baron and industrial investor, held the presidency between 1957 and 1969. H. L. Enman, who also chaired the board of the Bank of Nova Scotia, was appointed chairman of the board for iel.36 The belief in the omnipotence of the ownership class explains much about the province’s extensive commitment to the Clairtone Sound Corporation.

Clairtone was launched in Toronto in 1958 as the brainchild of Peter Munk, an entrepreneurial Hungarian immigrant and later chairman of Barrick Gold, and David Gilmour, the scion of a wealthy Canadian financial family who counted one of Winston Churchill’s grandchildren as a close friend.37 The company started producing stereo units, with Munk sourcing the components and Gilmour arranging for cabinet construction contracts. Munk would later describe the firm’s early years in Toronto as a quintessential entrepreneur story, as he and Gilmour created the original two units – a monoaural high-fidelity unit and a higher-priced stereophonic unit – and “survived by the skin of our teeth.”38 In the middle of this rags-to-riches account of plucky bootstrapping, Munk offhandedly mentions how they financed the early operation: “Luckily, I was given the number of … the Governor of the Bank of Canada. I phoned him personally and explained what was at stake. … The next day, our underwriters said they could find a way to get us the money.”39 The aesthetic of the new company, from its advertisements to its stereo cabinets, was peak midcentury modern. Its early annual reports bear glossy photographs of celebrities posing with Clairtone products. What images could better appeal to the industrial modernizers of Nova Scotia?

Robert Stanfield, Frank Sobey, and Peter Munk inspect a model of the Nova Scotia Plant.

“Clairtone Sound 1964 Annual Report,” mg 3 vol. 2218, file 2, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax. Reproduced by permission from Nova Scotia Archives.

Munk had little compunction about pressuring government to create favourable conditions for his company’s growth. In the summer of 1963, he drafted a brief to Mitchell Sharp, the federal Minister of Trade and Commerce, requesting that the government of Canada reduce tariffs so that Clairtone might expand its market share within the United States. He highlights the national importance of his enterprise, writing, “Our product [is] designed and manufactured entirely by ourselves entirely in Canada, and fabricated largely from Canadian raw materials.”40 This was not simply the boisterous confidence of a 30-something executive seeking greater profits through expansion; rather, it was Munk’s attempt – before even relocating to Nova Scotia – to halt the trouble that the company was expecting for the first quarter of 1964. In a somewhat panicked letter to Gilmour, written in the fall of 1963, Munk suggests that avoiding the appearance of financial difficulty was essential for maintaining the management’s reputational “capability and credibility” that would allow the company to “expand [and] raise money.”41

Part of the Clairtone response was to move toward a vertically integrated model; in 1962, the company purchased the Middlesex Furniture Company of Strathroy, Ontario, which had been its primary cabinet supplier. Next, Clairtone hoped to move into electronics component assembly.42 As a result, Munk and Gilmour were both pleased when they received a call in August 1964 from iel board member J. C. MacKeen, who explained that Nova Scotia was interested in courting the company for relocation.43 Within months, a deal was inked that would see Clairtone establish a manufacturing plant in Stellarton in exchange for nearly $8 million in subsidy.44 This would take the form of $2.5 million in financing for the construction of the factory, $1 million to finance the purchasing and installation of equipment, and additional moneys for further construction, as required by Clairtone. There was also to be $500,000 for “settling in” costs, and additional moneys were possible to offset things like transportation costs and other infrastructure.45

Stellarton was not a random choice for the relocation. In addition to being the hometown of iel president Frank Sobey, whose son was also the town’s mayor, it was part of a county staring down the barrel of deindustrialization in coal. The previous decade had not been kind to the workers in the Stellarton coal mines; the Pictou coal seam had a long history of trauma and mine disaster. On a cold day in January 1952, nineteen miners were killed and three were taken to hospital after a gas explosion tore through the McGregor Mine.46 The town’s two remaining collieries, the Albion Mine and the McGregor Mine, closed in 1955 and 1957, respectively – both as the result of fire in the pits. The town also had a long history of labour disputes within the mining industry, including a major strike in 1934 and the long association of the coal miners with the umwa.47 The history of workers’ organization and solidarity in Nova Scotia proved something of a concern both for Munk and for the management at iel.

Even before the deal was officially inked, Clairtone representatives were expressing wariness over labour relations at the new factory. In a confidential letter dated 5 October 1964, the vice-president of finance writes, “During the first five years of Clairtone’s activities in Nova Scotia it was imperative that uninterrupted production be assured. This would be a function of good relationships between management and labour. … [It will be] essential to ensure a reasonably long term contract [since] Clairtone would be highly vulnerable to the consequence of labour unrest. … Mr. Munk requested iel’s assistance in creating a five year contract … Colonel McKeen felt that this would establish a precedent.”48 This was reified in Clairtone’s internal documents, which highlight wage rates and a history of unionization as possible negative aspects of relocating to Nova Scotia. A comparative report, conducted to assess the viability of Beaverbank (Halifax/Dartmouth), New Glasgow/Stellarton, and Sydney, Cape Breton, noted that the heavily unionized male labour force in Sydney was paid nearly 26 cents more per hour than comparable wage workers in Pictou County. The file also notes that “female workers would be available for an average of 80¢ per hour but in Sydney they still expect $1.25 per hour.”49 This ability to exploit women workers was significant in the decision to relocate to Stellarton, as approximately half of the factory’s workforce would be women employed on the assembly line.50 Although the decision was made to relocate, this issue of Nova Scotians’ tendency toward organized labour would remain an issue for Munk and Gilmour throughout Clairtone’s operation.

Clairtone Assembly Line.

“Clairtone Sound Corp Pictou Estates,” mg 3, vol. 2218, File 4, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Reproduced by permission from Nova Scotia Archives.

At its peak, Clairtone employed around 1,200 workers, more than half of whom were women, in their factory on Acadia Avenue – just a few hundred yards from the site of the former coal mine. For many of the women who worked at Clairtone, the company provided their first experience in a factory workplace. Mary Adabelle Campbell, for example, had worked as a teacher before marrying and transitioning to working on the family farm alongside her husband. When Clairtone opened in Stellarton, Campbell applied for work on the electronics assembly line. As the firm declined, she was laid off. Unlike many of the men who had worked at Clairtone and subsequently been transitioned to work at Michelin – another iel project – Campbell left the manufacturing workforce entirely before finding employment as an egg grader at a farm in nearby Churchville.51 Other women eventually found their way to Michelin. Ella MacNeil, for example, had been in her early twenties when she responded to the call for employees at Clairtone. Laid off after working there for several years, she changed careers to work at a bedding store. Eventually, however, she also found employment at Michelin, where she worked for 34 years.52 Campbell and MacNeil were among the thousands of women who joined the waged labour force in Nova Scotia in the mid-1960s, responding to rising inflation and rising male unemployment in the primary industries.53 As Joan Sangster describes, the “feminization” of the Canadian workforce also relied on the expansion of economic growth in “community, business, and personal services,” where a multitude of women found employment during the 1960s.54

Clairtone’s male employees frequently came from farther afield. Charlie d’Entremont, an Acadian man from the south shore of Nova Scotia, describes leaving West Pubnico as a purposeful step away from the traditional fishing industry where he had worked alongside his father, uncle, and nephews fishing lobster and swordfish. Two of his nephews would ultimately be killed while working in the fishery. After attending vocational school in Yarmouth, he interviewed with Clairtone and moved to Stellarton at the age of eighteen in June of 1965.55 Contrasting his experiences at Clairtone with his previous work at fish plants on the south shore of the province, d’Entremont highlights the cleanliness of the factory and the physical division of the shop floor. Cabinetry was assembled in one wing of the Clairtone building, while electronics work, packaging, and shipping were located elsewhere on the same property.56 His continued use of the word “clean” to describe work processes at the plant and the physical surroundings of the factory stands in stark contrast to his earlier work experiences and matches with the image of Clairtone put forward in the firm’s advertising. In a press release, the company specifically contrasted the sleek, modern, futuristic style of electronic manufacturing with the dismal horizons facing the province’s cornerstone industries: “Not long ago, Pictou County could have been called the forgotten corner of North America … At one time, Stellarton boasted half a dozen coal mines …. Depressed, stagnating, and with serious unemployment problems, Pictou County’s gloomy prospects caused many of its people … to break their historic ties to the area. … Suddenly, dramatically, this has all changed.”57 Of course, there were parts of this industrial program that did not differ substantially from the forces that had governed coal and steel for a century. While the “coal masters” of early 20th-century Nova Scotia would not have recognized the aesthetics of the Clairtone factory floor, they certainly would have aligned with the owners’ skepticism toward organized labour. This, too, suggests the importance of recognizing class relationships as a constituent part of the importation and operations of Clairtone.

Workers at Clairtone were represented by the United Steelworkers of America (uswa) beginning in 1964. With management expressing concern over the length of contracts even prior to the move to Stellarton, it is unsurprising that the business archive includes a variety of pamphlets detailing how executives should try to mitigate the influence of a union within the workplace.58 The full extent of this distrust became clear between November 1966 and February 1967, when the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (ibew) sought to represent the Clairtone workers. Earlier in 1966, the ibew had challenged the uswa under the jurisdictional section of the Canadian Labour Congress (clc) constitution. Procedurally, this conflict should have been forwarded to an arbitrator for a final decision. If the arbitrator found against the uswa in favour of ibew jurisdiction, the Clairtone workers would no longer be able to be represented by the Steelworkers. Perhaps fearing this result, uswa national director William Mahoney reached an agreement with ibew vice-president William Landyman – sanctioned by the clc – to hold a vote among the rank and file at Clairtone during the open contract period. Within the uswa, this was a controversial decision; the president of the Clairtone Local viewed it as a betrayal by the national union.59 Catching wind of this, and incensed at the possibility of a contract disruption, Clairtone’s legal counsel, Donald McKillop, wrote to Jim Nicholson, the uswa director for District 2, accusing him of a conspiracy against the company and threatening to hold the union responsible for any financial losses caused by the matter. 60 As a result, the uswa backed away from the agreement, stalling the proposed vote, and in response the ibew began an independent card drive at Clairtone that was soon decried as a “raid” by uswa representatives.61

Tempers quickly flared. In February 1967, ibew organizer George Petta was brusquely escorted off Clairtone property for trying to hand out union pamphlets. Clairtone also blocked a combined attempt by the uswa and ibew to hold meetings or distribute pamphlets inside the plant during break times.62 At the same time, the company released an internal document to its managers detailing the “attitude to be taken if contacted by union/press.” The recommendation was to try to connect, in the public sphere, recent layoffs at the plant with the ongoing labour dispute.63 Nor was this solely the internal line; Sobey, speaking from Barbados to a Chronicle Herald reporter, excoriated the ibew “raid” – and threatened closure of the plant. “If the plant shut down,” he said, “it would be because of union and labour troubles that had plagued the … company for some time.”64

Complicating this further, an independent union – the Clairtone Employees Independent Union (ceiu) – emerged at the end of January 1967 to organize workers at the plant outside of the international union structures. ibew and uswa organizers immediately issued statements describing it as a “company union,” an accusation that Clairtone management flatly denied.65 In an open letter to ceiu organizer Allan Rendel, ibew representatives M. J. LeBlanc and George Petta accuse him of receiving money from management to organize the independent union and challenge what they term the “preferential treatment” of being allowed to hold meetings inside the factory.66 The ceiu issued a response, noting that its funding came from rank-and-file members and not management. In regard to what outside advice the ceiu was receiving, the letter insists that the matter was not the concern of “foreigners” within the ibew.67

Despite the denials from the ceiu and management, the notion of an independent union had been considered as early as November of 1966. Members of Clairtone’s management appear to indicate that they would prefer an independent union to the international organizations. First, scribbled in red ink on a letter from McKillop received by manager Mike Chojnacki is the following scrawl: “We must decide on what we will do if steelworkers are being replaced by ibew. 1. Accept ibew. 2. A company union.”68 In a later letter, again from McKillop to Chojnacki, the solicitor writes, “I have received a pamphlet … I find it rather unusual that the ibew would use this type of propaganda … In my opinion, this pamphlet will raise the question in some of the minds of your employees as to whether or not it might be to their advantage to form their own employee association and remove themselves entirely from an International Representative.”69 Ultimately, and despite the great concern of the company, the point was moot. After the drive, ibew Local 2225 won the right to represent the Clairtone employees.70

In the end, the failure of Clairtone in Stellarton was unrelated to the slight differences between Nova Scotia wage rates or the effects of unionization on production of electronics or cabinets. Instead, it was rooted in a series of business mistakes made by company management in Toronto, by iel and its directors, and by the Province of Nova Scotia under Stanfield and, after July 1967, his successor G. I. “Ike” Smith. The decline of the firm is made clear in its annual reports. Despite sales reaching a record high of $11,263,800 in 1965 – an 18 per cent increase over the previous year – it was in February of 1966 that Clairtone announced its intention to turn to the production of colour televisions, a technology that the company believed would witness a surge in demand over the coming years.71 Journalist and amateur historian Garth Hopkins, who wrote an early popular history of Clairtone in 1978, argues that this decision was the beginning of the end for the company. Indeed, Munk and Gilmour would later insist that the decision to move into television was requested by iel – which offered $3 million in additional funding. Sobey and other iel directors disputed this charge.72 Once the decision was made, Clairtone’s problems began to spiral out of control.

Demand did indeed spike for colour televisions, but American buyers were not choosing Clairtone products in the volumes necessary to achieve profitability.73 Munk attempted to assuage shareholders’ concerns at the annual meeting in April 1967, noting that the company was pleased with the appearance and functionality of its new television sets. He asserted that lacklustre financial reports in early 1966 were starting to be overcome in the final quarter and insisted that early 1967 results were looking more profitable than any previous year. The “softness” of the Canadian market, Munk declared, was not the result of manufacturing inefficiency; rather, it was due to the “discriminatory and punitive tax structure” imposed by the government of Canada on electronic home entertainment items. According to Munk, a Clairtone unit that would cost the American consumer $599 cost the Canadian consumer $900 thanks to these tax structures.74 Notwithstanding this issue, Munk’s bullish predictions did not materialize. Losses began to increase, and by the summer of 1967 the company was again approaching iel for additional capital.

In August 1967, iel and Clairtone reached an agreement to staunch the financial bleeding. Clairtone held the position that it required nearly $2.5 million “to cover any cash deficiencies that the Company would experience until the end of the current fiscal year,” and that “remaining inventory should be liquidated as soon as possible.”75 It was decided that Clairtone would borrow $2 million from iel, and in exchange iel would gain nearly 75 per cent of the firm’s controlling shares: “Industrial Estates Limited will have control of Clairtone Sound Corporation Limited.”76 Just two months later, Munk and Gilmour were pushed out and iel’s J. W. Mangels was installed as Clairtone president. In March 1970, with nearly $13 million in debts, iel sold the remains of Clairtone to the Province of Nova Scotia, and with political commitment to the company waning, liquidation began in 1971.77

The memory of Clairtone’s failure to survive are bifurcated along class lines just as clearly as was its internal decision-making. Charlie d’Entremont describes a slow decline on the shop floor. “We were getting less and less units to build,” he recalls, “and the workforce was getting smaller.”78 Year after year, he describes, the workforce dwindled – especially after 1966 – until it was clear by the time of the provincial takeover that the company had failed to capture the American market. Although he eventually found work at Michelin, another company attracted to the province by iel, d’Entremont also reflects on the uncertainty of occupational pluralism in deindustrializing Pictou County. “Being from Nova Scotia,” he says, “a lot of people had part time work, for example, at the Trenton car plant, [and] people used to go fishing a lot.”79 For the men and women displaced by the closure of Clairtone, this experience represented a return to either precarity or other forms of work – whether the fishery, Michelin, or something else. Interestingly, the experience of working at Clairtone, although it lasted for only a few short years, clearly had an impact on the men and women of Pictou County. This was visible at the opening of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry’s 2016 exhibit “Glamour + Labour: Clairtone in Nova Scotia.” Former employees and their families came together at the event to discuss the friendships fostered on the shop floor at Clairtone, to share memories, and to reflect on their working lives during the five decades since the plant’s closure.80

Munk’s account of Clairtone’s decline and liquidation reads very differently. Toward the end of his tenure, he penned a letter to the Department of Education in which he leans heavily on the “lazy Maritimes” stereotype and complains about the quality of Nova Scotia’s workforce:

When [Clairtone] initially considered establishing a manufacturing facility at Stellarton … The company understood that a high unemployment factor existed within the … area, and that labour was not only available, but was anxious to be given job opportunities. … This simply has not proven to be the case. … As at July 12, 1967, the company found it necessary to hire 416 new employees as replacements for employees who left the company without apparent cause other than the fact that they had accumulated sufficient savings to temporarily justify retirement from the labour scene.81

Nina Munk, Peter’s daughter, would later express much the same sentiment: “Ask my father and David about the collapse of Clairtone and you’ll be told that the move to Nova Scotia killed their company.” In addition to problems with cost overruns and Nova Scotia’s poor road infrastructure, she cites a Clairtone internal memo that claimed “the general population [in Nova Scotia] is basically not geared to the manufacturing frenzy and especially the five-day workweek … The welfare situation is such that it has created conditions similar to Appalachia in the United States where the third generation is already on relief.”82 As for Gilmour, he puts it simply in his 2013 book, Start Up! The Life and Lessons of a Serial Entrepreneur, written from his private island, Wakaya, off the coast of Fiji:

The demise of Clairtone was not a pretty picture – a lesson about the dangers of mixing up business ventures with governments … My concerns about government, labour unions, and over-regulation may not have had their origins in the Clairtone debacle, but they certainly came of age with it … Peter and I formed alliances with forces that proved to be entirely opposed to the entrepreneurial spirit. We were shocked by the experience of watching our dream trampled by the anti-corporate agendas of unions and elected officials.83

These accounts are perhaps puzzling. The failure of Clairtone – a company that was financed on the shoulders of a phone call to the governor of the Bank of Canada, shown the near-infinite trust of the Stanfield administration, and handed millions of dollars in Nova Scotia taxpayer monies – was, in this view, the direct fault of workers and their pesky unions.

In the end, the history of Clairtone in Nova Scotia reveals the class forces inherent in the “development state” that emerged during the mid-1950s. Although government intervention (and nationalization, in some cases) was called for by the Nova Scotia workers’ movement dating back to the early 20th century, the system that emerged was a pantomime of this demand. Instead of being rooted in social justice, or in close collaboration with the men and women of the province and their trade unions, the industrial development model that blossomed between 1957 and 1972 was founded on a particular elite view of industrial development that wholeheartedly accepted the ability – and indeed the right – of individual controllers of capital to operate and direct the state levers of economic policy. In this sense, though it may appear a doppelganger of social democratic governance, this framework was quite reactionary. For Stanfield, it was only natural that the meritocrats like Sobey, Munk, and Gilmour would direct these efforts. The role of the province was to provide the necessary capital and support to offset the structural impacts of regional underdevelopment. For these men, this history might be fodder for introductory remarks at gala events, designed to highlight early business failures as evidence of entrepreneurial stick-to-itiveness. But for the men and women who called Clairtone their workplace, even if only for the few years it was in Stellarton, it remains part of a longer experience of deindustrialization on the Canadian periphery.

1. Lyndon Watkins, “Hi-Fi Firm Moves to Province,” Halifax Chronicle Herald, 19 November 1964.

2. Ian McKay, “Springhill, 1958,” in Gary Burrill and Ian McKay, eds. People, Resources, and Power: Critical Perspectives on Underdevelopment and Primary Industries in the Atlantic Region (Fredericton: Acadiensis, 1987), 162–190.

3. One of Clairtone’s stereos, the Project G, was included as a product placement in the 1965 film Marriage on the Rocks, which featured Frank Sinatra. These products remain in high demand among audiophiles and celebrities. See, for example, LeBron James, “Purchased this vintage record(vinyl) player for the crib!,” Twitter, 15 November 2021, 9:16 p.m., https://twitter.com/kingjames/status/1460416408127303681?lang=en.

4. Fred Burrill, “Re-developing Underdevelopment: An Agenda for New Histories of Capitalism in the Maritimes,” Acadiensis 48, 2 (2019): 188.

5. James P. Bickerton, Nova Scotia, Ottawa, and the Politics of Regional Development (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990); Dimitry Anastakis, “Building a ‘New Nova Scotia’: State Intervention, the Auto Industry, and the Case of Volvo in Halifax, 1963–1998,” Acadiensis 34, 1 (Autumn 2004): 3–30; William Langford, “Trans-Atlantic Sheep, Regional Development, and the Cape Breton Development Corporation, 1972–1982,” Acadiensis 46, 1 (Winter/Spring 2017): 24–48; Steven High, One Job Town: Work, Belonging and Betrayal in Northern Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018); Tim Strangleman, Voices of Guinness: An Oral History of the Park Royal Brewery (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Petra Dolata, “Complex Agency in the Great Acceleration: Women and Energy Transition in the Ruhr Area after 1945,” in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth Sandwell, eds., A New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021): 155–173.

6. E. R. Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity: The Maritimes and the Industrialization of Canada during the Second World War,” Acadiensis 15, 2 (Spring 1986): 5.

7. Don Nerbas, Dominion of Capital: The Politics of Big Business and the Crisis of the Canadian Bourgeoisie, 1914–1947 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 240.

8. For other Atlantic Canadian examples, see Gerhard P. Bassler, “‘Develop or Perish’: Joseph K. Smallwood and Newfoundland’s Quest for German Industry, 1949–1953,” Acadiensis 15, 2 (Spring 1986): 93; Lisa Passoli, “Bureaucratizing the Atlantic Revolution: The Saskatchewan Mafia in the New Brunswick Civil Service, 1960–1970,” Acadiensis 38, 1 (Winter/Spring 2009): 126–150.

9. Stephen T. Henderson, Angus L. Macdonald: A Provincial Liberal (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), 67.

10. Meaghan Beaton and Del Muise, “The Canso Causeway: Tartan Tourism, Industrial Development, and the Promise of Progress for Cape Breton,” Acadiensis 37, 2 (Summer/Autumn 2008): 40; Peter Clancy, “The Last Pre-modern Premier,” Acadiensis 37, 1 (Winter/Spring 2008): 137.

11. Henderson, Angus L. Macdonald, 60.

12. Nova Scotia, The Jones Report on Nova Scotia’s Economic Welfare within Confederation (Halifax: King’s Printer, 1934), 11.

13. Meeting minutes, Industrial Development Committee, Mayor’s Office, 6 August 1951, Halifax, file 1, 102-48A Industrial Development Committee Records, 1951–1979, Halifax Municipal Archives.

14. Meeting minutes, Joint Meeting of Taxation and Assessment Committee and Industrial Development Committee, Council Chambers, Halifax, 13 December 1951, file 1, 102-48A Industrial Development Committee Records, 1951–1979, Halifax Municipal Archives.

15. For a thorough description of emergent regionalist political sentiment among Atlantic Canadian premiers surrounding transportation policy, see Stephen T. Henderson, “A Defensive Alliance: The Maritime Provinces and the Turgeon Commission on Transportation, 1948–1951,” Acadiensis 35, 2 (Spring 2006): 63.

16. While the latter decision was made under the leadership of G. I. Smith rather than Stanfield, Smith served extensively under the Stanfield government, continued the same development approach, and only took leadership of the provincial party once Stanfield made the move to federal politics in 1967.

17. G. A. Rawlyk and Doug Brown, “The Historical Framework of the Maritimes and Confederation,” in G. A. Rawlyk, ed., The Atlantic Provinces and the Problems of Confederation (St. John’s: Breakwater, 1979), 8–9.

18. E. R. Forbes, The Maritime Rights Movement, 1919–1927: A Study in Canadian Regionalism (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1979), 37.

19. Forbes, Maritime Rights Movement, 124.

20. David Frank, “The 1920s: Class and Region, Resistance and Accommodation,” in E.R. Forbes and Del Muise, eds. The Atlantic Provinces in Confederation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 256.

21. Frank, “The 1920s,” 249–251.

22. David Frank, “In Search of C. B. Wade, Research Director and Labour Historian, 1944–1950,” Labour/Le Travail 79 (Spring 2017): 25.

23. Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Coal (Ottawa, 1947), 563.

24. Similar demands were made by striking miners in Pictou County and Cape Breton during the 1947 coal strike; see Courtney MacIsaac, “The Coal Miners on Strike: Cape Breton 1947,” MA thesis, University of New Brunswick, 2005, 42–44.

25. MacIsaac, “Coal Miners on Strike,” 78.

26. See Bickerton, Nova Scotia, 352n17.

27. Nerbas, Dominion of Capital, 240; Eleanor O’Donnell, “Leading the Way: An Unauthorized Guide to the Sobeys Empire,” in Burrill and McKay, eds. People, Resources, and Power, 49–51.

28. Peter Clancy, “Concerted Action on the Periphery? Voluntary Economic Planning in the New Nova Scotia,” Acadiensis 26, 2 (Spring 1997): 6.

29. “Minutes of the adjourned meeting of the directors of Industrial Estates Limited held in the Red Chamber of Province House, Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the 25th day of September, A.D. 1957, at the hour of 3.00 o’clock in the afternoon,” 25 September 1957, rg 55, Office of Economic Development fonds, vol. 11, Industrial Estates Limited administration files, file 9 (Industrial Estates Limited minutes), p. 1, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax (hereafter nsa).

30. Roy E. George, The Life and Times of Industrial Estates Limited (Halifax: Institute of Public Affairs, Dalhousie University, 1974), 29.

31. “Minutes of the Meeting of the Directors of Industrial Estates Limited held in the Board Room, Room #502, Bank of Nova Scotia Building, Halifax, Nova Scotia on the 11th of December A.D. 1958 at the hour of 2.00 o’clock in the afternoon,” rg 55, vol. 11, Industrial Estates Limited minutes, 1958, p. 3, nsa.

32. Springhill Dev. Corp minutes, 13 February 1959, rg 55, vol. 11, file 9 (1962), pp. 2–6, nsa.

33. Minutes of the […] Directors Meeting of Industrial Estates Limited, 11 December 1958, 3.

34. Very quickly it became clear that the provincial mining industry was facing a crisis; indeed, the Royal Commission on Coal had issued the following as one of its conclusions: “On level terms, coal from the Sydney coalfield can never hope to compete with alternative and competitive fuels in distant Canadian markets.” See Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Coal (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1960), 125.

35. See Richard Clippingdale, Robert Stanfield’s Canada: Perspectives of the Best Prime Minister We Never Had (Kingston: Queen’s University School of Policy Studies, 2008), 59–60.

36. George, Life and Times of Industrial Estates, 11.

37. David H. Gilmour, Start Up: Don’t Predict the Products of the Future, Create Them! (Wakaya Group, 2014), loc. 58, Kindle.

38. Peter Munk, “Peter Munk,” in Alex Herman, Paul Matthews, and Andrew Feindel, Kickstart: How Successful Canadians Got Started (Toronto: Dundurn, 2008), 161.

39. Munk, “Peter Munk,” 161.

40. Peter Munk to Mitchell Sharp, 30 August 1963, MG 3 Clairtone Sound Corporation fonds (hereafter, Clairtone fonds), box 2150, file 7, nsa.

41. Peter Munk to David Gilmour, 18 October 1963, Clairtone fonds, box 2151, file 9 (Master File, 1957–1963), nsa.

42. Garth Hopkins, The Rise and Fall of a Business Empire: Clairtone (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1978), 71.

43. Hopkins, Rise and Fall, 92.

44. Watkins, “Hi-Fi Firm Moves to Province”; Agreement for Sale and Purchase of $7,045,000 Principal Amount First Mortgage Bonds, Industrial Estates Limited and Clairtone Sound Corporation Ltd., November 1964, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2217, file 3 (Clairtone Relocation), pp. 1–55, nsa.

45. Zigmund A. Hahn, vice-president finance of Clairtone, to R. M. W. Manuge, iel, 5 October 1964; iel to Clairtone Sound Corporation Ltd., 14 October 1964, both in Clairtone fonds, vol. 2217, file 3 (Clairtone Relocation), pp. 1–5, nsa.

46. “Warning of Fire Smell Saved the Lives of Many Workers,” Chronicle Herald, 5 January 1952. The dead were Albert Moss, Winton Sample, Joe Nearing, Brenton White, Arthur Moss, R. H. McNutt, William MacLeod, Dave Russell, Ed Arthrell, John Mailman, Ed MacCallum, Robert Cunningham, Tom Carpenter, Robert Davidson, Sam Campbell, Archie Hayman, Bain Nicholson, James Wright, and Leonard Wheatley. See “The Dead,” Chronicle Herald, 15 January 1952.

47. Margaret E. McCallum, “The Acadia Coal Strike, 1934,” University of New Brunswick Law Journal 41 (1992): 178–196.

48. Hahn to Manuge, 5 October 1964, 3.

49. “Clairtone Feasibility Report in the Province of Nova Scotia,” 26 October 1964, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2217, file 5 (Feasibility Study on Plant Location), p. 10, nsa.

50. These women largely worked on the assembly line, though there were also women working various salaried positions. See Nova Scotia Salaried Personnel, n.d., Clairtone fonds, vol. 2217, file 3 (Clairtone Relocation), nsa.

51. “Mary Adabelle Campbell,” obituary, McLaren’s Funeral Home, November 2017. In author’s possession.

52. “Ella (MacNeil) Callahan,” obituary, The News (New Glasgow), 3 April 2018; see also “Beverly Doncaster,” obituary, InMemoriam.ca, 23 November 2014, http://www.inmemoriam.ca/view-announcement-462374-beverly-doncaster.html.

53. Della Stanley, “The 1960s: The Illusions and Realities of Progress,” in Forbes and Muise, Atlantic Provinces in Confederation, 453.

54. Joan Sangster, Transforming Labour: Women and Work in Postwar Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 20.

55. This interview was completed in an oral history “life stories” format, where workers were interviewed about their life experiences, entry into work, and experiences on the job. Interviews for this project were approved by the Research Ethics Board at Cape Breton University (Protocol #2021-149) and conform to the requirements of Canada’s Tri-Council.

56. Charlie d’Entremont, interview by the author, 23 September 2021.

57. Clairtone Corporation, “What It Means to the Area,” press release, n.d., Clairtone fonds, vol. 2217, file 6 (Plant Opening, 1966), p. 1, nsa.

58. Union folder, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4, nsa.

59. Donald J. McKillop to M. A. Chojnacki, 28 November 1966, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2173, file 1, nsa.

60. Donald J. McKillop to James C. Nicholson, 16 December 1966, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2173, file 1, nsa.

61. M. A. Chojnacki to D. Van Endenburg and P. Munk, 27 June 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4 (Union), nsa.

62. George Petta to Paul Beaumont, 2 February 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4 (Union), nsa.

63. Clairtone Corporation, “Not to Come in Contact with Press, re: Dispute,” n.d., Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4 (Union), nsa.

64. Quoted in Dulcie Conrad, “Labour Conflict at Clairtone,” Chronicle Herald, 9 March 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4 (Union), nsa.

65. “3 Unions Vie to Represent Clairtone Staff,” Globe and Mail, 10 February 1967.

66. “ibew – Open Letter to Allan Randall,” Evening News (New Glasgow), 2 February 1967.

67. Answers given in reply to open letter, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 4 (Union), nsa.

68. McKillop to Chojnacki, 28 November 1966.

69. Donald McKillop to M. Chojnacki, 27 December 1966, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2173, file 1, nsa.

70. ibew, The Electrical Workers Journal, December 1970, 36.

71. Clairtone Sound Corporation, Annual Report, 1965, 6; Purchase Agreement dated 30 December 1965 between Clairtone Sound Corporation Limited and Industrial Estates Limited, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2162, file 1 (iel-NS Commitments), nsa.

72. Hopkins, Rise and Fall, 111.

73. Clairtone Sound Corporation, Annual Report, 1966, 12–16; Peter Munk to Ray Jones, 7 October 1966, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2183, file 8 (Peter Munk), nsa.

74. “President’s Address to the Shareholders,” 28 April 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2159, file 10 (Shareholder’s Meeting), pp. 5–6, nsa.

75. “Minutes of a Meeting of the Board of Directors of Clairtone,” 22 August 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2167, file 13 (Board of Directors, 1967), p. 1, nsa.

76. “Minutes,” 22 August 1967, 3.

77. Hopkins, Rise and Fall, 162.

78. D’Entremont, interview.

79. D’Entremont, interview.

80. “Glamour + Labour: Clairtone in Nova Scotia,” exhibit, August 2016–January 2017, Museum of Industry, Stellarton, Nova Scotia.

81. Peter Munk to Darrell Mills, 7 September 1967, Clairtone fonds, vol. 2183, file 8 (Peter Munk), pp. 1–3, nsa.

82. Nina Munk, “Peter Munk, David Gilmour, and the Memory of Clairtone,” in Nina Munk and Rachel Gotlieb, The Art of Clairtone: The Making of a Design Icon, 1958–1971 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2008), n.p., http://ninamunk.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Nina_Essay_Clairtone_optimized.pdf.

83. Gilmour, Start Up!, loc. 383, loc. 402.

How to cite:

Lachlan MacKinnon, “Importing the Clairtone Sound: Political Economy, Regionalism, and Deindustrialization in Pictou County,” Labour/Le Travail 91 (Spring 2023): 147–168. https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2023v91.009

Copyright © 2023 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2023.