Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Presentation / Présentation

A Hero from Capitalism’s Hells: Mike Davis and the Fighting Spirit of Socialist Possibility

“Fasten your seatbelts. It’s going to be a bumpy ride.” —Bette Davis, All About Eve (1950)

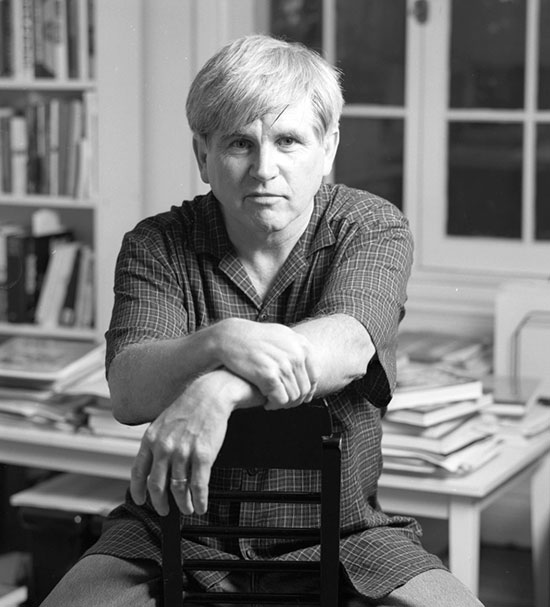

Mike Davis, Pasadena, 1998.

Courtesy of Anne Fishbein.

Suffolk County, New York, October 2000 was my introduction to the brutalizing racist blood sport of “beaner-hopping.” I spent one early morning chauffeured around small Long Island towns by Mike Davis. He took me to corners where dozens of Latino men gathered, shoulders hunched in the chilly autumn morning air, waiting for vans to pull to the curb, size up the muscle available, and direct a chosen few labourers to cram themselves into what space was left inside the vehicle. They would then be taken to various job sites, paid off the books a minimalist wage for a day of drudgery, hauling, heaving, hammering, and handling whatever they found themselves tasked to work with. Mike explained how these largely undocumented workers would make their way to 5:00 a.m. modern-day “shape-ups” week after week, many times returning to their cramped, unsanitary living quarters empty handed. Their thoughts were of home, knowing that families and extended kin in Mexico or Guatemala might go hungry that week for lack of a remittance.

Violence was on the rise against this floating reserve army of labour, which subsisted beneath the surface relations of dominantly white, seemingly affluent, communities. Anglo youth gangs from privileged high schools had taken to randomly targeting the immigrant, largely Spanish-speaking poor, running the often bicycle-riding newcomers off the road, taunting them and pelting beleaguered human targets with beer bottles tossed from tire-squealing cars. The harassment and physical intimidation, according to Mike, was escalating: pepper-sprayings, beatings with baseball bats, even potshots with bb guns were not unusual. He told me this with anger and despair as we discussed his most recent book, Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the US City (2000). That study explored the consequences of putting the new Latin American immigrants “where they clearly belong: in the center of debate about the future of the American city.” It ended with Mike’s characteristic belief that class struggle and class organization could overcome the burden of oppression carried by all peoples of colour, including Suffolk County’s 21st-century “tired, poor, huddled masses” of downtrodden, displaced peoples from the Global South. They would rise, he felt, as they had to, creating a “labor-Latino alliance” like the one that surfaced in Los Angeles in the late 1990s. “Class organization in the workplace,” Mike concluded in Magical Urbanism, was “the most powerful strategy for ensuring the representation of immigrants’ socio-economic as well as cultural and linguistic rights in the new century ahead. The emerging Latino metropolis will then wear a proud union label.” But Mike knew full well that Suffolk County, and much of America, was a long way from LA. As he glanced out the window at the often forlorn-looking street corners, their massed “menials” desperate for just one day of miserably remunerated work, Mike’s shoulders drooped and his countenance darkened. There was in his demeanour a worried acknowledgement of what Suffolk County’s Latino immigrants were up against.1

Cause for concern was clearly warranted. As I would later learn, the inevitably inadequate official crime statistics suggested that between 2003 and 2007 anti-Latino hate crimes jumped 40 per cent across the United States. In 2008 an Ecuadorian immigrant, Marcelo Lucero, was murdered in the Suffolk County village of Patchogue, New York. The killing of Lucero, a 37-year-old dry-cleaning store worker who wired money home to his relatives regularly, was carried out by a marauding mob proclaiming themselves the Caucasian Crew. They assailed their victim for hours, stalking him, frustrated when he evaded their intimidations and racist slurs. Eventually Lucero’s tormenters came across him again, cornering the now terrified man menacingly; when Lucero struck back with a belt, a seventeen-year-old star football and lacrosse player pulled a knife and fatally stabbed the Ecuadorian worker. The “beaner-hopping” that Mike told me about in 2000 became national news. “I don’t do this very often,” one of the juvenile killers told police, “maybe once a week.” At least it was not a daily routine.2

I was with Davis because of a tragic death of a different kind. The Humanities Institute of the State University of New York at Stony Brook was hosting a conference titled “Radical Ideas in Conservative Times,” commemorating the life’s work of Michael Sprinker, at which I was presenting a paper. Sprinker died in 1999 from a massive coronary brought on by an almost decade-long battle with cancer. A Marxist literary critic of breadth, indefatigable editorial outreach, and boundless generosity, he was the co-founder, with Mike Davis, of Verso’s Haymarket series, a publication project dedicated to expanding left-wing understandings of the North American experience. Many of us felt Sprinker’s loss acutely, but it hit Mike Davis particularly hard. Davis thought Sprinker “the best friend I’ve ever had” and considered his death “simply an obscenity.” Mike valued people over all else. Once he befriended someone, a conscious act that usually entailed a political assessment, Mike’s loyalty was rock solid.3

The recent recipient of a MacArthur “Genius Grant,” Davis was teaching in Stony Brook’s history department at the time of the Sprinker conference and asked me to lecture to his students. After our reconnaissance of Suffolk County we went to lunch at a suburban diner and, done with the fare, departed for his afternoon class. As Mike pulled out of the parking lot onto a two-lane thoroughfare, I realized we were going in the wrong direction. I saw an arm jerk the steering wheel, and before I knew it the truck bounced over a median. We travelled across a grassy boulevard, dodging shrubs, and after a few seconds of uneasy rattles and a final clanking descent, we were back on the road, proceeding in the opposite direction.

The truck was apparently none the worse for wear. I was probably more shaken, although I tried not to show it. With Mike it was always a bumpy ride.4 He did not just “Question Authority,” he abhorred it. His radicalism rejected officialdoms of all kinds, often with irreverent mockery. If Mike did not always disdain face-to-face encounters with those in positions of political power, especially if he thought his influence might result in some good, he had no liking for them, telling Los Angeles journalist Jeff Weiss, “You can hardly believe these people. So many of them are just absolute nincompoops.” Offered an excursion to Bohemian Grove, a 2,700-acre stand of virgin forest north of San Francisco that served as a men’s-only retreat for the Reaganite rich to unleash their inner “Iron John” selves, Davis declined. He had no interest in hobnobbing with George Shultz and other plutocrats, whom he was convinced spent their time at the elite wilderness spa “peeing on redwoods and acting like 7-year-olds.” Invited by heads of state and the Vatican to discuss his book Planet of Slums (2006), Mike did not deign to reply, expressing no desire to sit down with the president of Argentina or the Pope.5 Strictures and conventions, unless they related to traditions associated with family life or were laid down to advance struggle and revolutionary resolve, meant little to Mike. Rules were, in general, there to be broken, risks to be taken.

Mike and the Mythologies of Mercurialism

This did not always wear well at the Soho digs of Verso Books and New Left Review (nlr), where I first met Mike in 1981. I turned up, unannounced, at the 7 Carlisle Street offices of the radical publisher (which would later move to its current 6 Meard Street location in 1985), where Davis was working. Mike was affability itself.

We went out to lunch “on the firm.” Pizza and beers turned into an afternoon of imbibing and the telling of tall tales. Mike’s were far more elevated than mine, ranging from his arrests and strike experiences to Black Panthers he had known. We ended up going over to see Brigid Loughran, whom Mike had met and married in Belfast a few years before. There was much talk of “the Troubles” that dominated Northern Ireland of the time, of the hunger strikes, and of Bobby Sands’ death at hm Prison Maze, regarded as murder at the hands of Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. At some point, Mike reached into a terrarium – the small London flat contained a number of them – and lifted a greenish translucent serpent lovingly out of the container. I gaped in wonder as he began affectionately stroking the snake’s head, its tongue flicking in and out, seemingly in adoring appreciation. Welcome to Mike’s world.6

At that point in time, this world was not what it would become. Virtually all of Mike Davis’ fame and notoriety was ahead of him, his celebrated texts years away. I knew him, by reputation, from his articles in Radical America and in Review, the journal of the State University of New York at Binghamton’s Braudel Center.7 The latter essay, a 60-plus-page critical analytic excursion through Michel Aglietta’s regulation school of capitalist crisis in the United States, no doubt caught the eye of Perry Anderson, nlr editor. Others in the journal’s orbit – managing editor Quintin Hoare, later to be an award-winning translator; the Croatian socialist historian Branka Magaš; and the political activist and future distinguished public intellectual Tariq Ali – already knew Mike through the International Marxist Group (img). Davis joined the img late in 1974, while living in Scotland, recruited by Ali and Chris Bambery after a Chile Solidarity Campaign meeting. Anderson, perhaps attracted to a kindred intellectual spirit with a comparable “gift for mapping large trends,” eventually persuaded Mike to come to work in the nlr office in 1980.8 The ride soon got bumpy.

Robin Blackburn, who took over as nlr editor in 1983, thought Mike’s “robust, American working-class style” charming but acknowledged, understatedly, that “tact wasn’t his strong suit.” Davis’ correspondence with those communicating with the nlr could shock some members of the editorial committee. Adam Shatz, who wrote a widely read Lingua Franca piece on Davis in 1997, was told that Mike was “very in-your-face about his identity” during his time at nlr. There were those working in the offices of the left-wing publisher who could be quite harsh in their judgements of Mike. Long-time nlr figure Alexander Cockburn was more understanding. “Mike is a very romantic guy,” Cockburn said, adding that he “has this image of himself as a working-class revolutionary.” Things got rather raucous toward the end of Mike’s mid-1980s tenure at the nlr. In the midst of a personal argument entirely separate from nlr work, Davis, whose terraria of exotic creatures had been relocated to the top-floor flat above nlr’s and Verso’s new Meard Street offices, overturned a glass container of snakes. As the reptiles slithered across the carpet, Mike’s colleagues were not amused. Pleas for Mike to return the serpents to their captivity bounced off books by Lucio Colletti, Chantal Mouffe, Sebastiano Timpanaro, and other Verso authors. It wasn’t his finest hour, as Mike laughingly noted: “If anyone was guilty of wild or outrageous behavior, it was me,” he confessed.9

Looking back at these years toward the end of his life, Mike would say, “I ended up staying most of the eighties in London, totally wrapped up in the whole strange world of the New Left Review. Some of the worst years of my life. I couldn’t wait to be back in Belfast. The real warmth in the British Isles, the real grit, is all in the north of England and Scotland. And Belfast.” Homesickness and an at-times-troubled private life were part of this melancholic assessment of his London sojourn, but Mike’s time at Carlisle and Meard Streets was not always smooth sailing either. Interviewed by Sam Dean for the Los Angeles Times in July 2022, Mike recalled that by the end of his stint with the nlr he had “totally od’ed with intellectuals and academia.”10 In what may have referred to a later factional controversy, Davis claimed to have basically been “forced out of Verso” after an internal split, that the publisher closed down the Haymarket series without bothering to consult with him or Sprinker – a pronouncement that others at the editorial helm of nlr/Verso would challenge. Mike was never entirely comfortable within the tight-knit nlr group, intimating to Shatz that among plebeians and patricians there were bound to be gulfs separating perspectives and politics. Differences in political sensibilities were evident, for instance, when Tariq Ali told Shatz, “Mike is an exceptionally astute analyst of the enemy, but if I were an American trade union leader I wouldn’t go to him to ask which way forward.” What Ali’s assessment missed was that Davis considered himself a revolutionary critic of such ensconced leaderships. No friend of the trade union bureaucracy, Mike was part of a long tradition of oppositionists hostile to “the misleaders of labour” that included William Z. Foster, James P. Cannon, and James Connolly. Mike’s proletarian origins, and the politics and posture that he was crafting out of them, thus existed in constant creative tension with a number of other nlr editors, however much they might agree on any number of important matters. In a moment of self-mockery, Mike allowed that “I’ve always had a sort of truck-stop attitude toward effete intellectuals.”11

Still, there was much good that came out of Mike’s London years, including how he envisioned writing of Los Angeles and the California he loved but feared was being destroyed. Working in the nlr/Verso offices put him in touch with a range of writers and thinkers on the left, including expatriate nlr royalty residing in the United States, like Alexander Cockburn, who had made a name for himself publishing in the New York Review of Books, Harper’s, Esquire, the Nation, and the Village Voice, and Anthony Barnett, who would go on to found openDemocracy in 2001. Mike and Alex would be fast friends in New York, although they would later fall out, their disagreements registered in political collisions over a number of matters.12 Barnett, a long-time contributor to nlr, remained close to Mike for the rest of his life.

As Davis left the nlr/Verso offices to return to the United States, he remained a valued and diligent contributor to the journal’s team and, for decades to come, a star in Verso’s stable of distinguished writers. Between 1980 and 2020, Mike Davis contributed 30 articles, editorials, and posts to nlr’s print journal and blog. Many of his books commenced as articles in the Review, and most of his projects, completed or on hold, were workshopped within the nlr. It was there that Mike tested out ideas, received stimulating commentary, and was pushed to clarify his positions and broaden his perspective with suggested readings. If he never quite shook his complex, at times troubled, personal relations with many mainstays of nlr/Verso, Mike nonetheless understood well what the publication venture meant to him and so many other left-wingers.

At Meard Street, Mike was also highly regarded, especially as time wore on and his contributions mounted. Over the course of his long 40-year ride with nlr/Verso, bumpy or no, Mike Davis was increasingly appreciated. This was not just because he brought many contributors to the Review’s and Verso’s attention and was always a powerful and memorable participant in editorial committee discussions. Mike was also recognized, admiringly and affectionately, as sui generis, an irreverent, resilient, romantic, revolutionary voice whose originality, panache, and brio were as unequalled as they were, in certain circles, venerated.13

In this he shared something with another dissident voice who prefigured Davis’ sometimes rocky but always productive relations with the nlr. Although he differed from a predecessor like Edward Thompson in myriad ways, Mike Davis shared with Thompson a capacity for defiant refusals and adamant stands that shocked many at the same time they were exalted by others. Both Thompson and Davis insisted that anger, so often considered a deforming lapse among those in erudite circles who should be striving for objective and judicious intellectual contributions, was a legitimate emotion, one capable of expressing, even driving, the necessary passion of research and writing, as well as principles of political opposition. Davis was blunt in a 2020 interview: “What you need is a deep commitment to resistance and a fighting spirit and anger. Anybody who mortgages their activism to something like the success of a [Bernie] Sanders campaign, that isn’t commitment.” Like Thompson, Davis clearly thought the communication of anger a genuine response to a history that so often demanded indignation.14 Mike pulled no punches. His comment on the much-maligned Los Angeles chief of police, William H. Parker, in Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (2020) makes this abundantly clear: “1966 was a grim year for social justice, but it had one bright spot. At a testimonial dinner in July and in front of hundreds of guests, Chief Parker keeled over dead.” Outrage at the tens of millions killed by Empire’s constructed famines animated Davis’ writing in Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (2000). The book that Perry Anderson regarded as “Mike’s masterpiece” and that Tariq Ali praised as “a veritable Black Book of liberal capitalism,” was written to establish that “imperial policies toward starving ‘subjects’ were often the exact moral equivalent of bombs dropped from 18,000 feet.”15

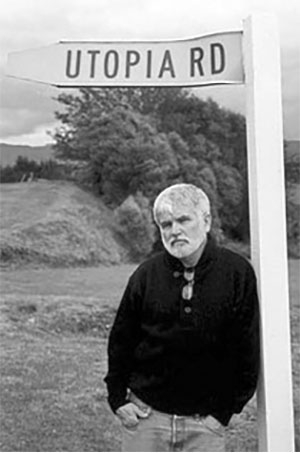

New York, 1999.

Courtesy of Alessandra Moctezuma.

Conservative historians found this kind of thing disquieting. Gertrude Himmelfarb, for instance, excoriated Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963), declaring, “Thompson is not merely engagé … he is enragé.” Rather like some might describe Mike. Both Thompson and Davis were well known for tearing strips – most well deserved, a few not – off comrades whom they felt “had gone astray.” Eric Hobsbawm said of Thompson that he had the gift of genius and for this his “admirers forgave him much. … His friends forgave him everything.”16 Again, not unlike Mike.

Born under a Bad Sign

Michael Ryan Davis, always known as Mike, was born on 10 March 1946 in Fontana, California, a “gritty blue-collar town” with an “unsavory reputation in the eyes of San Bernardino County’s moral crusaders and middle-class boosters.” Birthplace of the Hells Angels, Fontana’s destiny – in Davis’ later depiction of it as a place of shipwrecked “hopes and visions” – reflected “the fate of those suburbanized California working classes who cling to their tarnished dreams at the far edge of the L.A. galaxy.” Hunter S. Thompson described the kind of setting in which Mike’s early to mid-teenage years would nurture alienations of various kinds, within which was shadowed a precocious, if suppressed, intellectual attraction to natural science, books, and ideas. Post–World War II Fontana, according to Thompson, was founded on a class quest, not for order but for privacy, a need to “figure things out. It was a nervous, downhill feeling, a mean kind of Angst that always comes out of wars … a compressed sense of time on the outer limits of fatalism.” Fontana, according to Davis, was a “loud, brawling mosaic of working-class cultures,” where “designer living” meant a Peterbilt rig “with a custom sleeper or a full-chrome Harley hog.”17

This was a background that would stay with Davis for decades. During a 2003 tour of Bostonia’s El Cajon Boulevard, near San Diego, where the Davis family would relocate in the 1950s, Mike guided a bemused journalist interested in his story toward Dumont’s Tavern, a biker hangout in which the bartender sported Hells Angels colours. “You don’t mind if we get beat up, do you?” asked Davis mischievously. The figure from the Fourth Estate, sweating buckets in the hot Californian sun, came to the conclusion that Mike “stands with those of whatever stripe who picket, subvert, refuse allegiance to and revolt against the corporate, cultural, and political interests that control our lives.” This included biker outlaws, with whom the celebrated radical author shared a “kindred vision.” A founding Fontana member of the Hells Angels offered a pithy rendition of the gang’s oppositional optic: “We’re bastards to the world, and they’re bastards to us.” Or, in the words of Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.” This seems a fitting inscription on the tombstone of Fontana’s asphyxiated aspirations. The El Cajon that Davis grew up in mimicked this miasma: a racist frontier, part white cowboy, part militarist, and part downright degenerate, the town exuded evil. Looking back on his childhood, Davis told an interviewer in 2008, “I actually believe that I have seen the devil or his moral equivalent in El Cajon.”18

What was a boy brought up in this milieu to do? Certainly nothing good. Mike’s parents, who supposedly had fled Ohio and hitchhiked to California in search of the sunshine dream during the Great Depression, were not the types to resign themselves to his increasingly questionable behaviours, which spelled trouble. In Mike’s high school years an initial attraction to the armed forces – and an ideological affinity with American Cold War prejudices – was quickly overtaken by the lure of hellraising, especially if it involved fast cars. His mother and father were at their wits’ end as Mike’s carousing, and fixation on hot rods, took a detour into delinquency. But they were not entirely in sync in terms of how to handle a rebellious-without-a-cause teenaged offspring. His father, Dwight, a Protestant of Welsh background with a passion for geology that he passed on to his son, was a meat-cutting trade unionist who voted the Democratic ticket; Mike’s mother, Mary, was a tougher-than-nails Irish-Catholic Republican who had political eyes only for Calvin Coolidge.

A month shy of his eighteenth birthday, Mike was injured in his own personal Valentine’s Day massacre, in which the main victim was supposedly a powder blue Chevy he plowed into a wall when drag racing with friends. As Mike recovered in hospital, his father brought him a copy of Ray Ginger’s The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Debs (1949), hoping to wean him off the dragster pulps that monopolized his son’s reading time. Paperbacks like Henry Gregor Felson’s Street Rod (1953) were not really appreciated in the Davis household, whose texts of choice were the Bible and Reader’s Digest collections in patented faux-leather bindings. Dwight Davis no doubt thought published pap that might be read as glamorizing wild teenagers in souped-up cherry red roadsters contributed to his offspring’s dangerous nighttime escapades. A little Debs couldn’t hurt, thought Davis’ father, even if the old socialist was hardly lionized in Democratic Party circles. Mary Davis, no “mushy liberal,” had a different perspective. She hinted that a stint in juvenile detention, or even some hard time at San Quentin, would do her son more good. Yet, glancing at the Debs volume, she did allow that her Republican daddy had nurtured a soft spot for the beloved Gene, voting for the Socialist candidate when he ran for the presidency from his jail cell in 1920.19

Mike’s cultivation of the persona of a hot-rodding hellion was also well underway in his mid-teens, but it may have been accelerated and then channelled in new directions by a family crisis. Dwight Davis suffered a near-fatal heart attack when Mike was sixteen, his hospitalization depriving the family of a traditional breadwinner’s earnings and, along with mounting medical bills, placing it in precarious circumstances. Mary Davis pulled her boy out of school for a semester so he could earn some now much-needed money working for a Bostonia meat plant owned by Mike’s uncle. The young Davis ended up driving a delivery truck. An old friend of his father, Lee Gregovich – a blacklisted Communist who sold the Wobbly paper, the Industrial Worker, as a boy – was working at a Chicken Shack outlet on Davis’ route. Mike would stop in and have political conversations with his “Red godfather.”

Race, as much as class, however, animated Mike’s early transition from western redneck to 1960s radical, with family connections again a catalyst. His involvement in the civil rights movement and, in particular, the Congress of Racial Equality (core), was prompted when a cousin married the Black activist Jim Stone, who introduced Mike to the struggle against segregation and racial discrimination. A 1962 core demonstration at the lily-white Bank of America in downtown San Diego proved to be what Davis later referred to as a “burning bush” moment in his political evolution. He came close to actually going up in flames. Some yokel sailors sprayed lighter fluid on core placards, threatening to set them ablaze. Davis sat down on them as an act of preservation. He too was doused with the accelerant, the racist mariners flicking their Zippo lighters in the background. Mike claimed he was rescued by the paramilitary security wing of the Nation of Islam, whose crisply uniformed members, while not participating in civil rights demonstrations, often monitored them to ensure the safety of their dominantly African American participants. Under Stone’s tutelage, a teenaged Mike worked in the San Diego offices of core, an experience he would later describe as life-altering. Gregovich, proud of his friend Dwight’s son and the young man’s turn to civil rights activism, nonetheless urged him to take his politics to another level. “Read Marx,” the seasoned socialist advised.20

Sixties Schoolings

Davis did not exactly immerse himself in the works of “the Moor.” He did finish high school and then made his way to Portland’s Reed College in 1964, the first in his family to attend university. But he was soon enveloped in a crisis of class confidence. “I couldn’t write a word and I was just overwhelmed,” he recalled. Convinced that he lacked the ability to cut it among the literate sons and daughters of the liberal-arts college milieu, Davis disappeared from classes in a haze of rule-breaking sex and drinking. Mike and his girlfriend – the daughter of a Harvard Medical School professor – were expelled for the antiquated violation of “intervisitation,” a medieval-sounding prohibition that kept men and women from crossing the cohabitation threshold in their respectively segregated dormitories. Mike was actually ahead of the 1960s radicalization curve. May 1968 had its origins in Nanterre protests against University of Paris restrictions on dorm visits. Mike was on his way to “1968” a few years ahead of his Parisian confrères.

Unable to face his mother, who was outraged that her son, graced with a college acceptance, was wasting his chance at an education and was dropping out (Mike may have failed to tell her about the intervisitation imbroglio), a footloose Davis took the advice of Jeremy Brecher. The future labour historian with a flair for popularizing high points of class struggle was a proponent of the fledgling Students for a Democratic Society (sds). He pointed Mike in the direction of a new vocation, organizing radical youth, telling the expelled student he was not really college material anyway. sds needed help in its national office. Davis boarded a Greyhound bus for New York City as fall gave way to winter in 1964.21

There he became a full-time rabble-rouser in the beginnings of the American New Left. Mike’s description of his sds duties was eloquently self-deprecating: he was a “star envelope-stuffer and mimeograph-masseur.”22 Along with Todd Gitlin and others, Davis organized an anti-apartheid rally and sit-in that targeted Chase Manhattan Bank’s complicity in sustaining the segregationist order, bailing out South Africa in the aftermath of the Sharpeville Massacre’s economic fallout. sds buttons reading “chase manhattan, partner in apartheid” began to be sported on all kinds of apparel in New York City. The bank, flustered in the face of this public shaming, actually went to court to enjoin the student organization from distributing the embarrassing insignia and encouraging it to be worn by those sympathetic to the anti-apartheid cause. But with tens of thousands of the protest badges in circulation, the attempt to stifle the mobilization against American capital shoring up a racist regime fizzled. The 19 March 1965 demonstration at the Wall Street headquarters of the Rockefeller-owned bastion of finance capital was a united front “Blow for Freedom.” It was endorsed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (sncc), core, the Pan-African Student Organization, the Organization of African Unity, the American Committee on Africa, the National Student Christian Federation, the Newark Community Union Project, and other bodies. Gitlin and 40 or so others, “mannerly, well-dressed, with arms linked,” sat down on the sidewalk in front of the Chase Manhattan building until they were lifted into paddy wagons, transported to jail cells, and processed in the legal system. Onlookers chanted “Fascist cops!”23

No one in sds thought of Mike as a writer. He considered himself “functionally illiterate” at the time, maintaining that it was not until the mid-1970s that he began to overcome this limitation. Mike claimed that as a child his family was worried by his staccato-like speech delivery. His words seemed to jumble into one another, and there was concern that the youngster might be afflicted with developmental problems. Carl Ogelsby, sds president at the time, whom Mike admired as a mentor, leader, and riveting orator, described Davis as an organizational foot soldier, the most “meat-and-potatoes guy” in a student-based movement that boasted too few proletarian proponents. Ogelsby, like Davis, came from a working-class background, his “face cratered from a poor white childhood” lived in the shadows of Akron, Ohio, rubber plants, where his father, a migrant from the hills of North Carolina, worked.24

As sds grew, a peripatetic Davis would tramp the country on its behalf, touching down in Texas but spending the bulk of his time in Los Angeles. When Watts imploded in 1965, Davis furnished the organization’s offices with street purchases of typewriters and various fixtures, courtesy of some market-minded looters. An ill-fated attempt to set up an sds community project in African American West Oakland came to naught. Davis made a pilgrimage to Jackie Robinson’s mother’s house, hoping to be helpful in the struggle against the construction of a Pasadena freeway bisecting a historic Black district. The meeting ended with the matriarch of the neighbourhood metaphorically patting the well-meaning Mike on the knee and saying, “I think it would be better for you to go organize some white kids against racism. This community can take care of itself.”

Davis’ sds days in Los Angeles mushroomed into connections with a remarkable group of multiracial radicals and organizers. First among a distinguished corps of militant equals was the formidable and dedicated South Central activist Levi Kingston, Mike’s “Mephistopheles,” who showed the young radical “the ropes in LA,” introducing him to the city’s activists. Fifty years later Mike would dedicate Set the Night on Fire to Kingston. Los Angeles City College radical Ron Everett, later known as Ron/Maulana Karenga and founder of US Organization, the largest Black cultural nationalist group that consolidated in the aftermath of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, also crossed paths with Davis. The young organizer learned a great deal from two formidable and charismatic sds women, Margaret Thorpe at the University of Southern California and Patty Lee Parmalee at the University of California, Irvine. Finally, there was the legendary Chicana activist Betita Martínez, a.k.a. Elizabeth Sutherland Martínez, formerly head of the Friends of sncc, ny chapter, who remembered Mike as “that little kid from New York.”

As the days and nights of meetings, rallies, protests, and schmoozing blurred into one another, Mike’s romance with revolutionary possibility blossomed. At the summer 1965 anti–Vietnam War teach-in at Berkeley, Mike was electrified by hearing Isaac Deutscher, the Polish Marxist and biographer of Leon Trotsky, whom he thought for a moment actually was Trotsky. After years of Cold War restriction on his right to speak in public during research visits to the United States, Deutscher was finally allowed to address American audiences. His presentation to 15,000 protesting students was mesmerizing, a brief oration that Davis thought a kind of séance with a world entirely foreign to the young activist, a communing with dead revolutionaries and conjuring of memories and meanings of “betrayed revolutions.” To Mike, the talk was nothing less than “an assertion of intellectual sovereignty of a kind I had never seen before.” He would later suggest that the Deutscher speech lived with him for the rest of his life and perhaps propelled him onto subsequent paths of inquiry. Davis also claimed to have gotten drunk with Herbert Marcuse, who was evidently tiring of graduate students and welcomed Mike and a small contingent of antiwar working-class militants to his home. The heralded Frankfurt School thinker provided beer and wondrous stories of running messages for Rosa Luxemburg in 1918 that captivated Davis and his comrades.

Burning his draft card, the young sdser without a school was inevitably involved in the anti–Vietnam War movement. He was outlaw enough – in spite of a crewcut and phobia about recreational drugs – to hook up with some rampaging teenagers from the Palisades High School. Their riotous evenings on LA’s Sunset Strip would be forever etched in Mike’s memory: “The battle over the urban night had joined forces with the revolution.” Davis ended the 1960s in a police bus, arrested at San Fernando’s Valley State University, now known as California State University, Northridge. A peaceful November campus sit-in, where 3,000 students and sdsers protested the college administration’s banning of all demonstrations and rallies, culminated in the largest mass arrest of the decade, with 286 youths corralled into custody and transported to jail. Davis remembered the ride to the hoosegow 45 years later: “The girls started singing. ‘Hey Jude, don’t be afraid.’ I fell in love with all of them.”25

A Stalinist Sojourn

Like many 1960s radicals, Davis was in motion toward Marxism. Students for a Democratic Society was never a paying gig that provided even enough to live on. Moreover, as the mobilizing initiatives of the mid-to-late 1960s descended into the performative acts of the Weather Underground, a wing of the newly christened Revolutionary Youth Movements, Davis departed the movement in 1968 disaffected with the political trajectory of sds. Wild was all right, but as a politics of opposition it demanded the hard, day-to-day grind of Depression-era organizers or 1960s civil rights Freedom Riders. Davis never forgave the Weather Underground, regarding them as “rich kids, along with some ordinary kids, playing ‘Zabriskie Point’ for themselves.” He resented their role in the New Left’s denouement, which registered on his class-inflected political radar screen as a defeat.26 Retrospectively, Mike was looking for the left-wing way, appreciating the need for “organizations of organizers.” He may have been attracted to Maoism, but in 1968 it was the Communist Party USA (cpusa) that drew him into its ranks.27

No one influenced Mike more than the First Lady of California Communism, Dorothy Healey. Under her guidance, and alongside Angela Davis, Mike joined the Communist Party, noting Healey’s “bold opposition to the Soviet murder of the Prague Spring” and the Party’s “multiracial membership.” Again, it would prove a bumpy ride, involving ongoing arguments with Healey over a wide range of issues, but Davis never lost his admiration for her or the intransigent class-struggle politics of Third Period Communist militants he thought represented one of the best strands in the historic weave of American radicalism.28

For a time, Mike ran the cpusa’s Los Angeles storefront operation, the Progressive Bookstore. Squirrelled away in the basement of the shop was Mike’s rifle. At night he might sneak off into the desert for target shooting practice, blasting away at watermelons, or so he told me. Something of a self-identified “wild man” in the movement, Davis’ most serious indiscretion, however, was not so much his adventurism as his non-sectarian inclinations. As a Communist Party member, his “deviant” ideas may well have included attraction not only to the liberalizing push of the Prague Spring but to the Chinese Cultural Revolution. He was ordering literature the entrenched Stalinist Russophiles thought suspect at best, heretical at worst. Doing his utmost to appeal to a broad and youthful left seeking out all sides of the revolutionary road, Davis found a place for Trotsky and Bukharin, Mao and Marcuse, on the shelves he stocked.29

Mike’s days of drawing a Party stipend were undoubtedly numbered. Whether he was finally given the heave-ho for a physical altercation with a Soviet emissary, as he liked to suggest, or expelled as part of a loose Maoist “faction” remains an open question. According to Davis, his days in the Communist Party came to a grinding halt when he mistook a Soviet attaché for one of the fbi guys whose offices were nearby. These meddlesome types used to pop in to let the Party know tabs were being kept on it. The Russian official, dressed in dark suit, white shirt, and tie like one of Hoover’s men, spent an inordinate amount of time in the store, taking notes of titles on display. No one other than the Feds, thought Mike and an ex-navy friend who also harboured a rifle in the bookstore basement, wore these kinds of clothes and had an interest in writing down titles of what was for sale in a Party storefront operation. They decided to physically toss the suspected federal agent to the curb. Later that evening, Healey phoned Davis. “You’ve always wanted to be a working-class hero. Now you have to go out and get a job and become one. … You’re fired!” Turns out the Soviet cultural attaché wasted no time in letting Gus Hall, cpusa chairman, know that he had been “attacked by young Trotskyists or Maoists in the Party’s bookstore.” Mike had to get a day job.30

“A Working-Class Hero Is Something to Be”

Undaunted by this encounter with Moscow, Mike camped out in a dilapidated commune squat on Crown Hill, where he was befriended by a small-town gambler who resembled a character out of John Fante’s semi-autobiographical Depression-era novel, Ask the Dust (1939). This new acquaintance regaled Mike with tales of LA’s Downtown and Bunker Hill before the slum clearances of the 1960s and the invasion of the body-snatching freeways. To cash a paycheque, Mike enrolled in a Teamster training program and learned to drive an eighteen-wheel truck. His first job put him in the cabin of a concrete mixer, but Mike was fired when he lost his concentration. Mesmerized by the iron workers traipsing across steel girders to build skyscrapers, whom he thought more enthralling than the circus, Mike let his load spill down a major LA north–south artery, Figueroa Street. No matter, those were the days when jobs were there for the taking. He landed on his well-paid feet, delivering Barbie dolls throughout Southern California for the toy distributor Pensick and Gordon.

Davis was in his element. He worked 80-hour weeks nine months of the year, earning big money for the early 1970s, and had the post-Christmas winter slack time off to hike in the San Gabriel Mountains. As summer smog gave way to the allure of early autumn and he picked up work in the lushness of spring, the terrain was breathtaking and Mike found the long hauls “beautiful.” Always interested in geography and geology, Davis recalled decades later, “I loved doing that job.” But the warehouse supervisor, a charismatic Korean War veteran with ties to the Mexican American White Fence gang of the Boyle Heights neighbourhood, engineered an employment grab: his buddies from East LA moved into the better-paying trucking jobs. This left Davis and others whose cavalier attitude toward seniority – they liked their winter weeks off – open to displacement. Lesson One in the protocols of proletarianization: it was not so much what you know as who you know, and in Los Angeles the ties that bind were often racial and ethnic.

Soon Mike was driving a tour bus, guided toward the job by a Black organizer with the Teamsters, who gave him a heads up that the Gray Line Company was hiring. He offered sightseeing visitors to Los Angeles an endless patter on the fantasy sites of Disneyland and Hollywood by Night, all the while cultivating an alternative rap on the underside of the city. The normal practice for new hires at Gray Line was to purchase a set of tour talking points from one of the established drivers. This haughty lot regarded knowledge of Los Angeles as a proprietary sheet, to be sold for a whack-load of money. Bucking this tradition of commodification, Mike constructed his own commentary, some of which borrowed from anecdotes and accounts passed on by his hard-living Crown Hill friend. But he also began to read LA history seriously for the first time, starting with Carey McWilliams and Louis Adamic. As his store of knowledge increased, Mike supplemented the routine tour stops and commentaries with, for example, new visits to where white mobs massacred scores of Chinese in 1870 or talks on how the McNamara brothers bombed the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. The blue-rinse, suited-up side of Gray Line’s clientele was not always amused with Mike’s tales of working-class dynamiters, picket line stands, or bloody battles; more often than not, they seemed distressed. Yet there were longshore and plantation workers from Hawaii who warmed to Mike’s pitch. Their union sponsored group holidays and contracted them with the tour company. Kibitzing with this more proletarian element endeared Davis to the job. “I just absolutely had a ball with them,” he enthused decades later. The seeds of Mike’s Tartarean view of the City of Flowers and Sunshine lay in these years.31

Davis got into trucking as a kind of individualized “industrialization,” as it would be known in the new communist movements of the 1970s. The Teamsters, with an early rank-and-file push for more democratic unionism in the making, seemed fertile ground for cultivating labour resistance. Mike had no luck on this front. As a political influence on his brothers in the over-the-road teamster fraternity he was a dud. Reading Marx, Sartre, and Marcuse when he could scrape some time together, Mike found his working-class counterparts anything but left wing. “At night we’d go out to topless bars and I’d blurt out, ‘I’m a communist,’ and they’d say, ‘Dick’s a Jehovah’s Witness. Let’s have another drink.” Nonetheless, Davis found that his “coveted niche in the trucking industry” would be cut out from underneath him in a nightmarish descent into the violence never far from the surface of American class relations. At least that is the lore, which may well owe something to Davis’ willingness to embellish the truth with a “fabulist” finish. He was fond of saying that it startled him “to find out that some tall tales I told are actually true.”32

Gray Line was a small outfit, likely family-owned, and as they moved to sell the firm its status as a cab drivers’ local suddenly loomed as a liability. Breaking the union became a priority. When the inevitable strike ensued, Gray Line turned to an army of for-hire strikebreaking bus drivers who cycled through the industry in the United States, leaving locally ensconced unions in tatters. One of these scabs drove into a picket line, knocking down a Gray Line striker. Mike was arrested, charged with assault and battery for allegedly hitting a professional strikebreaker with a union sign. He found himself in a room with 39 other angry drivers. Many of them were, in Mike’s later estimation, “pretty shady” characters. They decided to each ante up $400, hiring a pair of hit men to kill the leader of the blacklegs. Class struggle had a way of turning even the most conservative and seemingly cautious of workers into rough-riding militants. In what he maintained was “the best speech” of his life, Mike tried to reason with his fellow strikers. Insisting that solidarity was the answer, and that much could be gained by secondary picketing and convincing organized labour not to cross their lines, Mike pleaded with his co-workers to step back from their murderous conspiratorial folly. They were having none of it. “We’ve just gotta kill the motherfucker,” was the consensus of the room. Davis thought many of these bus drivers, with their permanent-press outfits and standardized, conventional tour commentaries, “namby-pamby.” When he later discovered that one of them had been a Flint sit-down striker, he was shocked. His arguments rejected, Mike was outvoted 39 to 1. He put up his $400, swore eternal secrecy on what the brotherhood of Gray Line drivers determined to do, and stood firm. Only the incompetence of the hired killers, whose plot was foiled before it even had a chance to unravel, saved a young Mike Davis and his out-of-control counterparts from serious jail time. As part of the strike settlement, Davis was fired, the court charges against him dropped.33

Marxist Maverick

Mike returned to university in the fall of 1973. Enrolling in the University of California, Los Angeles, at the age of 27, he already knew a number of scholar-organizers who had backed the Gray Line strikers. Among them was visiting professor Jon Amsden, who campaigned to unite student groups, staff members, and campus workers into one big union.34 In the history department, Robert Brenner was offering a seminar on Marx’s Das Kapital, reading it in the context of debates within Marxism on agrarian class struggles and the transition from feudalism to capitalism, crisis theory, and 20th-century economic history. “It was an exhilarating experience and gave me the intellectual confidence to pursue my own agenda of eclectic interests in political economy, labour history and urban ecology,” Davis would later write.35

Mike was moving from the eclectic radicalism of an sds activist into the clarifications of revolutionary politics. He remembered visits to San Francisco’s Mission District, where he crashed in the loft of Seymour Kramer, a comrade of Brenner’s and later a leader of the Bay Area’s School Bus Drivers Union. The two spent long nights arguing about the Portuguese Revolution and the latest articles in New Left Review, drafting manifestos and “circulating tracts by a certain Belgian economist,” Ernest Mandel. Mike would later describe the two of them as the smallest political party in the world: “I forget whether he was Lenin and I was Trotsky, or perhaps it was Abbot and Costello; but in any event we considered ourselves to be the apostles of regroupment to the Trotskyist left.” Any vestiges of Maoism were now gone. Davis and Kramer attended a demonstration at San Francisco’s dilapidated International Hotel, where elderly Filipino and Chinese bachelor immigrants – their lives constrained by racist “anti-miscegenation” laws – resided. The I-Hotel, a landmark of the city’s once-thriving “Manilatown,” was earmarked for development by the gentrifying Four Seasons Corporation. Poor and elderly tenants were threatened with eviction. Activist groups such as I Wor Kuen, We Min She, the Asian Study Group, and the Union of Democratic Filipinos mobilized, but to no avail. The I-Hotel was ultimately demolished in 1977–78. At the protest he attended, Davis was alarmed to see rival political collectives break into kung-fu fighting among themselves. As he turned incredulously to Kramer, his wry friend was nonchalant: “Hit anyone you like. They’re all Maoists.”36

Restlessness, and a sense that an apprenticeship in Marxism was best served in the Old World, in those days roiled by labour militancy, got the better of Davis. A 1974–75 research scholarship from his father’s meat cutters’ union funded a year’s study in Scotland. A Glaswegian trucker warned Mike off living in Edinburgh, where his bursary was tenable at the large university, telling him the place was a deadly class purgatory. Glasgow, with its long tradition of labour militancy, seemed a more congenial setting. Mike touched base there with a young American grad student, Suzi Weissman, future biographer of Victor Serge, when he submitted an article on Preobrazhensky to Critique, a Marxian journal she was editing with Hillel Ticktin. Suzi was enthusiastic about meeting this precocious left-wing student from California, welcoming him into her circle of revolutionaries and refugees. Soon Mike was sharing her cold, damp Glasgow flat, crowded with Trotskyist MA and PhD candidates and Chileans fleeing the coup d’état that deposed the Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende, replacing it with a junta under the leadership of General Augusto Pinochet. Weissman and her compañero Roberto Naduris would be Mike’s lifelong friends.37

Nevertheless, it was Belfast that really drew Mike, who began visiting frequently from Scotland, hunkering down for much of his scholarship year in the library to research the Depression-era outdoor relief protests, when Catholics and Protestants rioted together. Even after that research period had run its course, he would return to Belfast from the United States, reconnecting with his mates and widening his social and political contacts. He lived for a time in Belfast’s Holylands district behind the university – the streets were variously named Palestine, Jerusalem, Damascus, Cairo – finding love with Brigid Loughran, who grew up in the war-torn neighbourhood of Ardoyne. “The Troubles” hung over everything, of course, but Mike found himself at home in a working-class community where he “formed some of the deepest friendships of my life.” He was moved deeply by the “unadorned eloquence and moral clarity” of Bernadette Devlin McAliskey. From the rooftop of Belfast’s Busy Bee Market, she delivered an inspirational address “the apocalyptic day the hunger striker Bobby Sands died.” The atmosphere of a nation at war was all pervasive: “I felt like we were existentialists in the French Resistance, because my friends faced extraordinary risks and really didn’t worry about it too much … we stayed up all night … playing the guitar, telling stories, slagging and being slagged.” His love of Belfast notwithstanding, Mike’s 1980s would be spent, for the most part, in London.38

At New Left Review

Contacts with img militants in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast, and London during the 1970s proved to be Mike’s letter of introduction to nlr. He first met the journal’s editor, Perry Anderson, in the autumn of 1976, when the two men were brought together by Branka Magaš. Mike recalled a long talk in which he spoke of “this idea I had for writing a book about the American working class.” His scholarship year having come to a close, Mike returned to Los Angeles, intent on finishing his undergraduate degree, the thought of writing a history of American labour taking shape but by no means fully developed. In December 1976, Mike received a letter from nlr asking him to write on the US left.

Davis replied in January 1977 with twelve pages of closely typed theses – “a sample of the form of analysis that I think needs to be made.” At the crossroads of a new historical period, American labour seemed “lost in a troubled sleep.” Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky had “clung to a spontaneist optimism” that the US working class would “catch up” in giant strides, claiming its “rightful place” in the leadership of the world labour movement. Only a few fragmentary writings grasped the specificity of American conditions: Gramsci in “Americanism and Fordism” and Trotsky in his last writings on trade unionism in the epoch of imperialist decay. A historical assessment demanded taking into account the relation between the strong and stable bourgeois-democratic structures of the United States, on the one hand, and the intense state repression and ruling-class violence routinely inflicted on workers, on the other. At the same time, the class itself was in a constant state of turbulent re-composition, through immigration and internal migration. Though the working class of the United States had not produced an independent labour party, it was nothing less than a “laboratory par excellence for the invention of militant forms of struggle and organization,” encompassing the municipal general strike, the sit-down strike, and the boycott. In response, New Left Books/Verso offered a contract and a $1,000 advance.39

Mike later claimed to be concerned that he could actually complete the study. For a time, he returned to truck driving, but his enthusiasm for the job soured. Irish friends came to visit him on the West Coast, and he travelled to Belfast, further nurturing his attraction to the city and the relationships forged there, including with Brigid Loughran. When, in 1980, Anderson invited Davis to relocate to London to work on his book and help edit nlr, Mike accepted the offer. He once again departed California, but this time without any clear date of return. During his 1980s work with the Review and its book-publishing arm, Verso, Davis began to hone his skills as a writer, developing a unique style that was both captivating and combative. He published a stream of articles in the London-based journal, starting with his two-part study of the history of the American working class, followed by a path-breaking analysis of Reaganite neoliberalism – “Like the Beast of the apocalypse, Reaganism has slouched out of the Sunbelt, devouring liberal senators and Great Society programmes in its path” – and a prescient study of the political-economic shocks heralding the arrival of a new, post-Fordist regime of accumulation, based on overconsumption and low-wage employment.40

Davis joined the nlr editorial committee in the early 1980s at a moment of intensive debates over Edward Thompson’s “Exterminism” theses on Reagan’s new-generation nuclear weapons and the escalation of the arms race, with its threat of star wars. Thompson championed the European Nuclear Disarmament (end) movement. Mike contributed a forceful essay on the subject, insisting that the politics of disarmament must extend to the truly international realm, recognizing that global instability in the nuclear age was hardly confined to the Cold War animosities freezing the Soviet Union and the United States in an escalating arms race trending toward Armageddon. Refusing to limit the purposes of the peace movement to the “restoration of a lost European or Northern civilization,” Davis called on those mobilizing against potential nuclear annihilation to nurture “the deepest levels of human solidarity.” Like Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto it was crucial to “point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality.”41

Arguments were raging during these years in nlr’s pages and on its editorial committee. Among the contentious topics were the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Solidarność in Poland, the Falklands War, the nature of the state, the origins of women’s oppression, the question of eco-socialism and “postmodernity” – “the cultural logic of late capitalism,” as Fredric Jameson defined it in a landmark nlr essay.42 One of Jameson’s prime examples was the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, with its reflector-glass cladding, towering atrium, miniature lake, and revolving lounge. In a polite but devastating reply, Mike retained the idea that such examples of a futuristic built environment held a key to deciphering larger patterns but set the Bonaventure within the tougher-minded political-economic periodization that his studies of Reaganism were developing: reckless overbuilding, as symptom of global capital flight from the developing world and the rise of new international rentier circuits, culminating in the definitive abandonment of the ideal of urban reform as marker of a stark class polarization in the United States. Above all, Mike stressed the savagery of the mega-hotel’s insertion into the surrounding city, where child labour and sweated homeworking were re-established amid levels of super-exploitation among inner-city LA’s million-strong undocumented migrant population.43

This initial encounter with Jameson bridged Davis’s 1970s-initiated examination of class formation and the political malaise of the American working class with his future studies of Los Angeles. Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class (1986), Mike Davis’ first book, was a product of these transatlantic happenings. It was an unconventional study steeped in conventionality. The argument percolated through the long-asked question of why the working class of the United States was different and had not formed a labour party or developed a socialist consciousness. Unlike the trend in left progressive academic scholarship of accenting the autonomies evident in proletarian districts and the seeming decision-making capacities of skilled labour in the workplaces of 19th- and early 20th-century capitalism, Davis chronicled the political immolation of a working-class captive of the American Dream, whose most effective prison-house was the Democratic Party and its legion of ideologues. Roosevelt and the New Deal were not, as they are presented in so many contemporary academic accounts, the saviours of working people, advancing the cause of trade unionism, but a lethal, bourgeois blow struck at the militant industrial organizing campaigns of the 1930s. American workers, acclimatized to decades of defeat and disillusionment, opted by the 1980s, according to Davis, for electoral abstentionism.

Described by one commentator as “the great antisentimentalist,” Davis wrote against a background of Reaganism’s successful assault on labour, “a grim coda” that left the prospects for revived class struggle politics slim indeed. Something of a cold shower visited on the pioneering histories of Herbert Gutman and David Montgomery, Prisoners of the American Dream presented a sweeping cartography of class formation: the exhilarating wave of Debsian socialism that Mike insisted derived from an immigrant proletariat exploited economically and disenfranchised politically was absorbed by the Fordist “Americanization” of the 1940s and 1950s. This destroyed the social and cultural base of nascent forms of socialism and communism. Forged through its compounded historical defeats, the US working class in this view acquired a “distinctly contradictory, battered, and lumpy form that could not be evened out by appeals to abstraction,” as one commentator summarized. Only radical protest – akin to the uprisings and direct-action tactics of the early to mid-1930s and 1960s – could resuscitate a genuinely left-wing labour movement, bringing the enervated trade unions back to life. This would only happen, however, to the extent that class struggles and the solidarity they would engender and depend on took an internationalist and antiracist turn, making common cause with liberation movements in the developing world and aligning unequivocally with Black and Latino communities of the United States. “The long-term future of the US left,” concluded Davis, “will depend on its ability to become both more representative and self-organized among its own ‘natural’ mass constituencies, and more integrally a wing of a new internationalism.”44

Writing the Modern Macabre in Southern California

Mike’s mother looked at Prisoners of the American Dream and asked, “You think anyone in the working class could possibly understand this?”45 Her judgement was unduly harsh. Yet it may well have prodded her son to greatness. In the years to come, Davis engaged in “learning to write.” He insisted it was “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.” Beginnings of articles or books stalled and sputtered as Davis agonized to strike just the right note in an introductory sentence; whole days at his desk evaporated as pages and paragraphs were rejected, and entire chapters once judged finally finished were condemned to the wastebasket. The rewards were tremendous. Mike would ultimately produce writing on Los Angeles that “surges off the page irresistibly, exciting and compelling in equal measure.” A trio of books that appeared in the 1990s won Davis wide recognition, financial windfalls, and a reputation as the single most important theorist slicing through the dystopian dimensions of American capitalism’s urban deformation.46

The first of these studies, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, is perhaps Davis’ finest book, a tour de force that counterposes the mythologies of the celestial city to the actualities of a hellish, human-engineered environment of predation and class-orchestrated confinement. Los Angeles, so often depicted as cosmopolitan, cultured, and chic, is presented by Davis as carceral. For Mike, the true ruler of the City of Angels was Lucifer: a mélange of ominous trends in which security systems, segregated spaces, brutalizing and intrusive policing, and ecological irrationality all contributed to the lethal oppression of a multi-ethnic working class.47

The book opens with Davis standing “on the sturdy cobblestone foundations of the General Assembly Hall of the Socialist city of Llano de Rio – Open Shop Los Angeles’s utopian antipode.” The first sentence of his excursion into the despair that he imagines orchestrated the evolution of LA insists that “The best place to view Los Angeles of the next millennium is from the ruins of its alternative future.” Mike visited what was left of the desert sanctuary, abandoned in 1918, to “see if the walls would talk to me.” They did not. Instead, the conversation came from two 20-year-old labourers from El Salvador, tramping California’s frontier of housing starts, camped out for a time in what was left of Llano’s old co-operative dairy. When Mike informed them that they were squatting in the remains of a ciudad socialista, the peripatetic tradesmen asked whether “rich people had come with planes and bombed them out.” They might as well have: the colony’s credit collapsed.

So begins a tour of Tinseltown and its environs, the very un-socialist Los Angeles. Chapters on authors who have socially constructed the city lead into discussions of moneyed power, monopolized land development, and watered dividends; the retrenchment of homeowners and white backlash; the fortress mentality that structures urban architecture and the mindset of the infamous lapd; and the political economy of urban gangs. LA is represented as a community of containment.

City of Quartz is a book like no other: against the boosterism of the mega-developers and their kept intellectuals, Mike lays bare a story of expropriation and exploitation, violence and venality, greed and gruesome pursuit of subordination, recounted with rare relish. LA, in this telling, has been pushed toward a Blade Runner–style descent into a guerrilla war fought on a diversity of fronts, from ucla to the streets of Compton. “In Los Angeles there are too many signs of approaching helter-skelter,” Davis warns, adding that “everywhere in the inner city, even in the forgotten poor-white boondocks with their zombie populations of speed-freaks, gangs are multiplying at a terrifying rate, cops are becoming more arrogant and trigger happy, and a whole generation is being shunted toward some impossible Armageddon.” Imaginative and rivetingly presented, City of Quartz closes with Davis’ birthplace, the “junkyard of dreams” that was Fontana, where homeboys proclaim their lot in life: “Eat shit and die.” Bourgeois hubris and hectoring insistence on prioritizing profit brought the Californian Dream’s roller coaster ride to a threateningly bumpy terminus, highlighting the “conflagrationist potential” of a city that would soon be engulfed in the flames of the Rodney King riots.48

On publication, City of Quartz gained immediate recognition as a terrific text, sold reasonably well, and drew critical acclaim. The acquittal of the four white policemen who viciously beat Rodney King changed everything. As Los Angeles erupted in the incendiary rage of the dispossessed, City of Quartz’s popularity soared. Mike’s reputation took a quantum leap forward. Seen as something of a seer, Davis apparently received a $160,000 advance from Knopf for a book on the riots. He decided to pass on the project because he was becoming close to former gang member Dewayne Holmes and others, advising them in their efforts to orchestrate a truce among the competing Bloods and Crips. Davis’ notoriety in American society, and within an international left, increased exponentially as he spent time hooking up unlikely African Americans whose lives constituted a constant battle against police and governing policies with political figures like two-time California Governor Jerry Brown and an old sds connection, Tom Hayden, now a Democratic Party member of the state assembly, 44th district. In the words of LA journalist Jeff Weiss, City of Quartz became “everyone’s favorite Rosetta Stone for translating the civic unrest.” The class enemies Davis eviscerated in City of Quartz no doubt seethed, but they were largely silent.49

Not so with the second instalment of Mike’s apocalyptic analysis of Los Angeles’ disaster trajectory, bankrolled by a $50,000 advance from Metropolitan, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company. Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (1998) outraged the city’s powerful development/real estate lobby, and it fought back. The book opens with what was now Davis’ trademark stylistic flair: “Once or twice each decade, Hawaii sends Los Angeles a big wet kiss.” That this puckering up brought destruction in its wake did not have to be said. (As I prepare this text for publication, millions of Californians are fleeing their homes or sheltering in place, besieged by torrential rains, unprecedented flooding, car-eating sinkholes, marauding mudslides, and trees toppling out of their waterlogged roots.) Shoring up the panache of this prelude was Mike’s turn to what he would subsequently, in Late Victorian Holocausts, dub “political ecology,” a marriage of environmental history and Marxist political economy. For the substance of Davis’ metaphor was the ruin of irregular, but inevitable, storm systems that sweep warm, water-laden air from the Hawaiian archipelago eastward, hurling massive rainfalls on the Sunshine City. As turbulent storm fronts collide with the mountain wall surrounding the Los Angeles Basin, the ferocity of the consequent rainfall – the equivalent of half of the city’s annual precipitation – can exceed even that of tropical monsoon belts. Devastation results. And so the stage was set for a depiction of LA as a city of potential calamity, an environment that inspires alarm. This did not go over well among those whose expense accounts, sales commissions, and extravagant living derive from the sunny imaginary of the City of Angels. They depend on boosting LA’s paradisiacal portfolio.50

This crowd did not exactly cotton to chilling tales of capitalism’s defiance of commonsensical care in building skyscrapers atop earthquake fault lines; casting caution to the winds of downpours and their destructive potential to unleash floods of biblical proportions; overdeveloping the natural habitat of potentially man-eating critters; or destroying biodiversity to the extent that waterlogged snakes wash up on prime beachfronts. Following Walter Benjamin, Mike presented Los Angeles as a dualistic dialectical fairy tale. In Part 1, “a relentless chain of slaughter and extinction stretching from the casual brutality of nineteenth-century ranching and market-hunting practices to the systematic predator extermination campaigns of the twentieth century, mounted in the name of ‘scientific’ game management,” saw roughly 11,000 bountied kills of mountain lions in Southern California between 1907 and 1950. Capital and the state strove to tame the wild natural environment of the West, cleansing a habitat the better to sanitize it for profit-taking. Part 2, however, saw the survival of nature’s wild offspring, “led by the astonishingly adaptive cougars of the Sierra Madre.” A habitat’s flora and fauna, slotted for domestication, even extinction, “begin to bite back, with often startling social consequences.” Reports from Descanso and Pasadena of large cats ambushing the residents of rich suburbs were bad enough. When Mike declared that wildlife’s evolutionary adaptations might presage the “emergence of nonlinear lions with a lusty appetite for slow, soft animals in spandex,” it was neither amusing nor good for business. Definitely in bad taste, whatever the cougars might have thought.

For Mike, however, the small, ordinary mammals of the chaparral belt posed greater threats to human life than the celebrated cougar. Rats, mice, and other vermin, vectors rather than predators, were a grave danger. Plagues and pandemics were in the making. Virus-carrying rodents threatened to overtake suburban tranquility, while tick-infested deer mice unloaded Lyme disease on an unsuspecting country-club set. Insects posed yet another menace: an Africanized bee population was apparently poised to marshal a deadly cyclone of winged killers unleashing an epidemic of anaphylaxis. As nature uncorked its resentments at humanly orchestrated violations of its realm, Davis closed his presentation of Los Angeles as the poster child of calamity with a glimpse of how the Californian conurbation might have looked from outer space during the riots of 1992. “The city that once hallucinated itself as an endless future without natural limits or social constraints” appeared from such Olympian heights as an urban setting of extraordinary inflammability. Los Angeles had all the “eerie beauty of an erupting volcano.” This was a stupendous sight, viewed from afar, but living atop an implosion in the making was quite another thing.51

Admittedly a tad over the top, all of this was less disturbing to the capitalist mindset than Mike’s signature chapter in Ecology of Fear, the searing exposé of LA’s class-ordered political economy of fire. In “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” Davis juxtaposed how the overcrowded tenement and welfare apartment-hotels of LA’s Westlake district, the city’s equivalent of Spanish Harlem, and the gilded coast of Malibu’s perfect beaches, impeccably outfitted cappuccino bars, and exorbitantly overpriced seaside estates confronted seemingly common incendiary destinies. LA’s Downtown district of poorly ventilated garment sweatshops and overcrowded, oven-like tenements was, by the 1970s, a slumlord’s dream. Rapacious rentier capital jammed families of recién llegados from Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala into firetrap bottom-end housing, where regulations, safety provisions, and maintenance were ignored. Between 1947 and 1993, roughly 120 people died in 14 fatal blazes within a one-mile radius of the corner of Wilshire and Figueroa. Meanwhile, across the class divide, in roughly the same time period, Malibu was the wildfire capital of North America: 13 massive, 10,000-plus-acre firestorms destroyed over 1,600 high-priced homes and took 16 lives, while approximately 2,000 smaller fires burned with less destructive intensity. The rich and the poor, apparently, were torched alike.

Mike took this lowest-common-denominator evasion of essential class difference and exploded it with scornful eloquence. Describing a 1993 conflagration that engulfed the Malibu coastal hills, burning celebrity mansions to their foundations and ensnarling the Pacific Coast Highway with a crawling parade of firefighting vehicles and fleeing Bentleys, Porches, and Jeep Cherokees, Davis reached into a deep, wry reservoir of class analysis. A couple of housewives of the rich and famous loaded their jewels and designer dogs into kayaks and took to the sea, rescued eventually by some fawning Baywatch boys from Redondo Beach. Davis’ punchline told it all. The women saved their pets and pendants but left their Latina maids on the beach. From there, the domestic servants made their perilous way to a safe coastline haven, but that outcome was by no means certain. That Davis failed to mention that the maids may not have been swimmers, perhaps fearing the ocean as much as the raging fire, and might not have wanted to accompany their employers in what they regarded as rather flimsy vessels, outraged critics. The elementary point remained: the low-paid help were left to their own devices while four-legged friends were cradled into kayaks. Class mattered in the fire zones of LA. It was the great divide, and being on the wrong side spelled disaster and death.52

Malibu existed as a natural wildfire ecology, a precarious habitat the rich colonized, developed, and sustained at a cost of hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of dollars annually. This was a social expenditure that capitalism – especially its financial sectors, like insurance and banking, and servile state authorities – was always willing to justify in neutral discourses of public safety, natural hazards, and protections necessarily and supposedly extended to all Californians. Where the urban wilds of Westlake were concerned, however, these same powerful class interests regarded welfare as a dirty word, immigration restriction as a rallying cry, and slumlord responsibilities to maintain buildings and keep them safe something to be sidestepped with a wink and a nod. Fire, an inevitable natural phenomenon in the coastal hills of Malibu, largely destroyed privatized property, which could always be rebuilt, the rich subsidized by the social provisioning of the public purse. Downtown LA, in contrast, burned not because it had to, but because it was profitable to allow it to go up in flames. This “disaster algorithm” registered in the deaths of tenement dwellers and lined the pockets of the owners of buildings blatantly in violation of almost every section of the minimalist building, safety, and fire codes.

With capital simply getting away with murder, Mike made the case, obviously somewhat tongue-in-cheek, for letting Malibu burn. It was inevitably going to. Investing in the infrastructure of the inner city, no natural inferno, so that it would not incinerate the poor was obviously the logical counterpart to this position. But when rational choice ran headlong into capitalism’s appetite for accumulation, it hit the brick wall of material interest. His hyperbolic header aside, Davis’ point was glaringly obvious: Why build and rebuild ostentatious palaces for the most conspicuous consumers and run up the tally of recurring costs associated with insuring and protecting them, when the cycle of natural wildfires was only going to necessitate having to go through the same thing again and again? It seemed a political economy of indulgent insanity.53

This was too much. As Ecology of Fear topped best-seller lists for seventeen weeks in 1998, a Malibu realtor initiated a crusade to discredit Davis. He pored over the book’s 484 pages and 831 footnotes and set up a website claiming Ecology of Fear was based on fabrications, his findings publicized under the subdued title “Research Exposes … Mike Davis as Purposively Misleading Liar.” Soon the mainstream media – the Economist, New York Times, and Los Angeles Times – jumped on the bandwagon. In the feeding frenzy that followed, Davis was depicted as a fraud; one columnist denounced his work as “fake, phoney, made-up, crackpot, bullshit.” What resulted from a mountain of heavy-handed claims, however, was a rather small molehill of minor, understandable, often inconsequential error and the inevitable clash of oppositional political readings of evidence.54

Mike’s entire history was now subject to hostile investigation. Charges that he was prone to make things up gained traction when it surfaced that Davis, always irreverent and defiant of rules, had concocted a 1989 piece for the LA Weekly on the Los Angeles River that purported to be an interview with an advocate of natural waterways – a dialogue that never took place. The subject of the essay, Lewis MacAdams, was in the late 1980s an ecology activist and leading figure in an advocacy group known as Friends of the Los Angeles River. MacAdams, who barely knew Davis and had engaged in conversation with him only in passing, was somewhat taken aback when Mike showed him a draft of the interview before publication. It was based on the two supposedly meeting at the Fremont Gate entrance to Elysian Park, a place MacAdams never frequented. Davis described MacAdams as showing him a tattered old map prepared for the Los Angeles city engineer, when, again, the social activist had never laid eyes on any such document. The interview Davis fabricated was, however, brilliantly and convincingly done. It presented MacAdams as an authority on the history of the river, the map that was unknown to him and that Davis unearthed at the Huntington Library rich in the kind of detail that would allow environmental groups to challenge the damaging and ill-conceived bureaucratic approaches to flood control. As Mike explained his semi-fictionalized approach, the flabbergasted environmental campaigner was won over. “I was the expert and the activist,” MacAdams later wrote, “but it was Davis who had put in my hands the blueprint for the restoration of the wetlands of the Los Angeles River.” MacAdams thought “the words he put in my mouth made me sound like I knew a lot more about the Los Angeles River than I actually did. I told him to go ahead with the piece just the way it was.” Both Mike and the LA Weekly would later admit that running the story in the way that Davis wrote it was wrong, but MacAdams was on board. For all the carping, Davis weathered these storms, becoming, in the words of Tom Hayden, “an oppositional figure” in the firmament of LA’s literary world, “a counterpoint to the bullshit that passes for intellectual discussion in this town.”55