Labour / Le Travail

Issue 91 (2023)

Deindustrializing Memory / La mémoire désindustrial

Curated Decay: Residual Industrialization at the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry

Abstract: Nova Scotians understand economic hardships at both the personal and community levels. This is especially true for the residents of Pictou County. With the eclipse of coal, steel, and heavy manufacturing, successive governments looked to tourism to augment an eroding economic base and to commemorate the working lives of Nova Scotians. This article offers an analysis of the initial decision to construct and maintain the Museum of Industry in a region of the province subjected to sequential phases of deindustrialization. The venture, officially opened to regular attendance in 1995, is the largest facility in the province’s impressive system of 28 regional museums. The creation of the museum, however, was fraught with uncertainty and narrowly avoided financial collapse and plans to disperse the collection of artifacts. The project was subsequently left straddling an uneasy divide between celebrating industrial heritage and tempering controversies of economic and environmental development. Despite Nova Scotia’s proud heritage of worker resistance and union activism, visitors may exit the museum with the ambiguous message that while working lives are often harsh and riven with uncertainty, optimism for the future must prevail. The implication is that the appropriate response is selective anodyne forms of nostalgia, even resignation, but not resentment of the human and environmental costs of deindustrialization.

Keywords: industrialization, deindustrialization, regional development, coal mining, public history, critical museum studies, working-class commemoration

Résumé : Les Néo-Écossais comprennent les difficultés économiques tant au niveau personnel que communautaire. Cela est particulièrement vrai pour les résidents du comté de Pictou. Avec l’éclipse du charbon, de l’acier et de la fabrication lourde, les gouvernements successifs se sont tournés vers le tourisme pour augmenter une base économique en érosion et pour commémorer la vie active des Néo-Écossais. Cet article propose une analyse de la décision initiale de construire et d’entretenir le Musée de l’Industrie dans une région de la province soumise à des phases successives de désindustrialisation. L’entreprise, officiellement ouverte à la fréquentation régulière en 1995, est la plus grande installation de l’impressionnant réseau de 28 musées régionaux de la province. La création du musée, cependant, était semée d’incertitudes et a évité de justesse l’effondrement financier et les plans de dispersion de la collection d’artefacts. Le projet a ensuite été laissé à cheval sur un fossé difficile entre la célébration du patrimoine industriel et la modération des controverses sur le développement économique et environnemental. Malgré le fier héritage de la Nouvelle-Écosse en matière de résistance des travailleurs et d’activisme syndical, les visiteurs peuvent quitter le musée avec le message ambigu que même si les vies professionnelles sont souvent dures et déchirées par l’incertitude, l’optimisme pour l’avenir doit prévaloir. L’implication est que la réponse appropriée est des formes anodines sélectives de nostalgie, voire de résignation, mais pas le ressentiment des coûts humains et environnementaux de la désindustrialisation.

Mots clefs : industrialisation, désindustrialisation, développement régional, charbonnage, histoire publique, études muséales critiques, commémoration de la classe ouvrière

Despite its officially cultivated image as “Canada’s Ocean Playground,” a quaint and timeless geography for prospective vacationers seeking refuge from the alienation of modernity, the province of Nova Scotia has experienced generations of harsh industrialization.1 Alongside the traditional maritime occupations of forestry, fishing, and seacoast trade there developed a reliance on heavy industry, which by the late 19th century included coal mining, steel production, and heavy manufacturing. One centre for these activities is Pictou County, encompassing the northeastern towns of New Glasgow, Westville, Trenton, and Stellarton.

As regional and international competition in coal and steel increased over the course of the 20th century, Nova Scotia, and especially Pictou, experienced sequential phases of industrial decline.2 When traditional resource extractive industries and secondary manufacturing declined, few viable alternatives arose. For Pictou County, this deterioration involved job losses in forestry, coal mining, pulp and paper, steel fabrication, and automotive tire production. Transient options such as call centres and part-time retail sales offered pallid replacements for the steady high-waged jobs that were lost.

Successive governments of Nova Scotia looked to tourism to augment an eroding economic base, and in Pictou County an institution called the Museum of Industry was built to commemorate the working lives of Nova Scotians. This article offers an analysis of the initial decision to construct and maintain the museum in a region of the province subjected to sequential phases of deindustrialization. This venture, officially opened to regular attendance in 1995, would become the largest facility in the province’s impressive system of 28 regional museums. It is one of the few Canadian cultural facilities focused on industrial heritage.3

The campaign to commemorate Nova Scotia’s industrial past was decades in the making. Beginning in the 1970s, community efforts focused on creating a new purpose-built museum of “transportation and industry” to be erected on land donated by the Sobeys, a prominent family of entrepreneurs linked to supermarket and retail sales, who continue to exert a measure of custodial control over depictions of popular history.4 That a “museum of industry” would be constructed to represent the heritage of northeastern Nova Scotia raised hope but also caveats. Would such a museum capture the complexity and nuance of industrialization, or would it display the artifacts of residual deindustrialization without sufficient context, as something of a freeze-dried tableau of faded experiences? Would this become a collection of curated decay?

The Museum of Industry was conceived as a boost to civic pride and tourism but also as a testament to the history of a province once at the cutting edge of technological innovation. An extensive research program was part of the initial planning, as 80 reports were commissioned from academics and other specialists. These formed the basis of the collection strategy. This research was supported by a special library with materials related to the technological and social history of Nova Scotia containing over 2,600 volumes. The resource has been restricted and is only available for limited public access as apparently little research has been conducted beyond the initial museum implementation.

Despite these early efforts in research and knowledge production, the Museum of Industry may best be understood as a late 20th-century part of what David Lowenthal terms the “heritage crusade.” For Lowenthal, the pursuit of heritage lends itself to an “improved past” often framed by a presentism that conveys celebratory depictions of history.5 While mindful of the distinctions between historical analyses of deindustrialization and the professional field of critical museum studies, this study of the Museum of Industry nevertheless suggests that heritage preservation projects of this nature ultimately diminish the past human and environmental costs of industrial expansion and fall short of assuaging the residual stigmatization of the communities and region. The interpretative gaps and silences of this museum foster collective amnesia rather than an appreciation of historical complexity. In this respect, missing complexity would combine the ambiguities of economic development tempered with a realistic appraisal of the ongoing generational human cost of industrialization.6

Peter Thompson observes a similar flattening of the past and the imposition of a progressive narrative at other Nova Scotian tourist sites that engage with the province’s industrial history: “Coal-mining museums in Nova Scotia at once convey enough destruction and discomfort to allow visitors to believe they are participating in an authentic experience and also romanticize these events, make them comprehensible, and place them in an overall narrative of sacrifice and development that views the fall of the industrial era as the first step in a shift to clean and efficient enterprises such as tourism.”7 Similarly, in Alberta, Lianne McTavish explored eleven museums and historic sites devoted to resource extraction and noted a bifurcation of curated messages. On one hand, resource development was viewed as an inevitable project of modernization and socially beneficial to these communities. Alternatively, museum displays could be read as suppressing the true human and environmental costs of extraction, including colonial land appropriation. This is especially evident with the Oil Sands Discovery Centre in Fort McMurray, where the exhibits overwhelmingly reinforce the economic benefits to be derived from exploiting nature with scant reference to the severe environmental degradation of the region.8 While the Sobey-led Museum of Industry is less constrained to a narrow corporate perspective, its permanent displays present a similar narrative of the necessity of pursuing resource extraction at every opportunity.

The literature on critical museum studies presents a considerable range of analytic tools with which to consider the Museum of Industry. Tony Bennett observed that museums should not be considered public spaces as they are not independent of state or private control and therefore cannot contest vested power.9 Bennett’s observation is applicable to the Museum of Industry, where the close relationship between successive provincial governments and the ever-dominant Sobey family has clearly influenced its representation of the region’s history. Svetlana Boym’s writings on nostalgia seem particularly relevant to the museum. Nostalgia, as Boym notes, is often taken as a loss or displacement or a somewhat romantic fantasy of yearning for a different time, yet it can also be “restorative” as it presents the opportunity for reflection.10 In terms of museums, institutionalized nostalgia offers revisionist interpretation of the past. Indeed, Boym observes, the “stronger the rhetoric of continuity with the historical past and emphasis on traditional values, the more selectively the past is presented.”11

The Museum of Industry cultivates nostalgia in a way that elides the long-term physical and emotional consequences of economic malaise in the region. Sherry Lee Linkon aptly dubs such consequences the “half-life of deindustrialization.” For affected communities, deindustrialization is “not an event of the past. It remains an active and significant part of the present. … In its half-life, deindustrialization may not be as poisonous as radioactive waste, though high rates of various illnesses as well as alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide suggest that it does manifest itself in physical disease.”12 Nostalgia for lost industrial ways of life, in this context, can hardly be restorative. The residual decay of deindustrialization is acknowledged at the museum but is made subservient to narratives about ongoing efforts to modernize and “improve” the community. Read against this narrative, continuing present-day economic distress implies that working-class people are to blame for their persistent problems.

Doreen Massey’s conception of the historical sense of place and “multiplicity of interpretations of place,” highlighting connections between the authentic local and its “interconnectedness” with global forces of capitalism, have resonance in northeastern Nova Scotia.13 The arrival of the British-based General Mining Association (gma) in 1826 immediately situated Pictou County at the forefront of large-scale resource extraction and manufacturing ventures. No rural backwater this, Nova Scotia would continue to push ahead aggressively through successive waves of industrial expansion into the late 20th century. With its gradual but inexecrable transformation to a largely post-industrial economy, some form of commemorative project was deemed necessary by both the provincial government and Sobey interests. If the narrative could be shaped to emphasize anodyne nostalgia and civic boosterism, troubling questions of failed economic policies might be avoided. Yet the dramatic shift from the traditional coal and steel industries in central Nova Scotia resulted in demographic changes that have left the region in decline.14

The Museum of Industry would be the incarnation of residual memory of former industrial might. To the present day, it continues to proudly display its collection of artifacts ranging from giant objects such as steel forging hammers to the intimate scale of miners’ acetylene lamps. The preservation and restoration of these items is without question an important contribution to the material history of the province. Displays of photographs mounted on large display panels provide visual references to the challenges of coal and steel production, yet they omit crucial elements of the story.15 To walk through exhibit galleries is to experience a curious disconnect. Industrial Nova Scotia’s vibrant past is hidden in plain sight – identified with artifacts and descriptive labels – but only in a manner that serves to disassociate past from present. The sorry litany of failed or failing industrial ventures from the 1950s onward forms a leitmotif in the ongoing travails of peripheral economies. While Pictou County struggled valiantly to keep afloat economically, each termination of a call centre, relocation of a tire manufacturing plant, or pulp mill closure is noted with a certain resignation as the memory of alternatives is erased.

After outlining the origins and early development of the Museum of Industry and situating it within the commemorative landscape of its community, this essay will explore the partiality of its engagement with Pictou County’s industrial and deindustrialized history with select examples. What do visitors learn about one of the region’s longest running and deadliest industries, coal mining? What of the series of often short-lived industrial operations that state subsidies and other inducements drew to the region in the post-1945 era? What will visitors leave the museum remembering? What does the museum encourage them to remember to forget?16

The Origins of the Museum of Industry

The ultimate realization of the Museum of Industry owed a great deal to the contributions of the Sobey family, notably the sustained efforts of William (Bill) Sobey, who championed the original concept of the museum in the 1970s and worked diligently to achieve this goal until his death in 1989. Yet such patronage came with caveats. Like other dominant Maritime entrepreneurial family names – such as Irving, McCain, Jodrey, Bragg, Risely, and Cooke – the Sobeys, through their holding entity Empire Company Limited, have long exerted a significant paternalistic grip on their home territory. The family’s corporate headquarters are within view of the museum. To counter their reputation as the “Pictou County Mafia,” the corporation engaged in a long-term strategy to bolster its image through charities and other philanthropy.17 Supporting the Museum of Industry was part of this strategy.

As “Canada’s Family Grocery Store,” Sobeys became dominant in the retail food sector with national and international subsidiaries, while advancing a corporate culture adverse to working-class activism and militancy.18 As a result, the Museum of Industry was left to negotiate carefully between historical evidence of a vibrant union culture and the larger narrative melding the co-operation of private enterprise and public funding.

The original initiative, known locally as the “Sobey project,” was to serve primarily as a railway museum and to highlight the two surviving locomotives – Samson and Albion – of the original six imported by the gma between 1838 and 1854.19 Given the tough economic situation of the 1970s, the remembrance of an illustrious past had tangible psychological benefits. The museum prospectus asserted that the use of advanced 19th-century rail technology was irrefutable evidence that the region represented the leading edge of modernization. Indeed, it claimed grandiosely, “Stellarton was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in British North America.”20 The locomotives had been celebrated as marvels of early steam technology and, once finished with gma tasks, were exhibited in the United States and later held at the Baltimore & Ohio Railway Museum until being returned to Nova Scotia in 1928. By the 1970s, Samson and Albion were in urgent need of restoration, and the opportunity to house them in the controlled setting of a new museum proved attractive to the town councils of New Glasgow and Stellarton, who owned the respective machines. Despite the closure of all underground mines that had originally necessitated the short-line railway, the anticipated visitors to the new museum might pause and marvel at these artifacts of Nova Scotia’s past industrial strength and accept the implication the province might continue to be globally competitive.

The proposed museum was to occupy the thirteen-acre site of the former Foord coal pit at Stellarton, the very location of what in 1866 was claimed to be the world’s deepest coal mining operation. The museum complex would house existing technology-related holdings but also actively collect items from the fast-disappearing industrial topography. From 1972, funding was readily available for non-federal projects through the Museums Assistance Program. This money was to be supplemented with contributions from regional development funds. At this point, the prospects seemed entirely positive for a permanent home for the artifacts and cultural story of the province’s industrial history.21

Albion locomotive, Museum of Industry, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

Despite these favourable conditions, plans stalled. The Museum of Industry was side-tracked by competing heritage projects, notably the high-profile Halifax-based Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, and it was not until 1983–84 that serious reconsideration of a transportation and technology museum resumed. The ensuing consultant’s study, Nova Scotia’s Museum of Industry: A Plan for Implementation (known as the Lord Report), laid out a detailed implementation plan for the Stellarton location, and two years later, the initial collection was assembled.22 The creation of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry in 1986 was intended, in the words of the Lord Report, “to inform Nova Scotians and their visitors of the province’s industrial past, to foster a keener appreciation of present-day industry, and to stimulate an awareness of the industrial potential of the future.”23 The report provided a thorough assessment of museum assets in the province and comparator industrial museums internationally. It also offered a synopsis of Nova Scotia’s history of development. It was assumed that the new museum would augment existing provincial interpretive sites and expand tourism.

By the 1970s, museum specialists Gail Dexter Lord and Barry Lord were well established in Canada. In 1977, Barry Lord authored Specialized Museums in Canada for the federal government while serving as assistant director of the Museums Assistance Program. The Lords co-authored Planning Our Museums for the National Museums of Canada in 1983. What became Lord Cultural Resources Planning and Management helped lead the dramatic expansion of heritage projects during this era when both federal and provincial governments were eager to define national and regional heritage. Prior to the Museum of Industry project, the Lords had prepared reports on provincial museums for Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island as federal and provincial governments rushed to open facilities that would define the national character. For the Lords, the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry was a comparatively minor project but one whose attempt to address the issue of industrialization was informed to some extent by a sensitive reading of the class dynamics of unequal capitalist development.24

Tensions immediately emerged between two conceptions of the Museum of Industry: on the one hand, as a potential “heritage experience” stopover for tourists heading east along the Trans-Canada Highway to Cape Breton, and on the other, as a thorough depiction of the region’s conflictual industrial history. While coal mining was intended to be a central feature, it was necessary to ensure that the new Pictou museum not encroach on the well-established Cape Breton Miners Museum at Glace Bay.25 While the Museum of Industry’s mandate was to acquire materials from across Nova Scotia, its initial focus was to be the industrial development of Pictou County. In a 1988 speech given at the sod-turning ceremony, Bill Sobey, a leading proponent of the museum concept, was enthusiastic about the museum’s prospects. “Pictou County has an amazing background of industrial technology and skills,” he noted, “covering mining, railroading, shipbuilding, steelmaking, steel rails and rail cars, glass making, sawmills … tire making, and pulp manufacturing.”26 Such boosterism was understandable, yet this optimistic start for the museum would be undercut by severe financial disruptions.

The museum’s construction was completed in the late 1980s, but this initial progress was followed by ongoing delays in its formally opening to the public. The 1993 election of the cost-cutting Liberal government of premier John Savage signalled an immediate crisis. Hostile to what was viewed as an initiative closely linked to former Conservative premiers John Buchanan and Donald Cameron, the new government was poised to cancel the project altogether, terminate the curatorial staff, and disperse or dispose of the collection of 15,000 items. When lawyers noted the liabilities assumed in reneging on agreements for items donated in trust to the province, the government reconsidered the consequences of withdrawal.27

Later in 1993, the Savage government ordered an end to direct state support and the hasty formation of community volunteers, known as the Friends of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry Society, salvaged what had been achieved to date.28 From a national perspective, the troubles at the Museum of Industry were hardly unique; many private and public initiatives, ranging in scale from Toronto’s Gardiner Museum and Calgary’s Glenbow Museum to the Canadian Museum of Human Rights and the Canadian Museum of History, have faced serious exhibit controversy and financial challenges.29

In Nova Scotia, intense efforts to lobby the Savage Liberals secured some additional funding, and the gala opening of the Museum of Industry finally occurred in June 1995. This was soon followed by reports from the “Friends” that the project’s financial viability was once again in jeopardy, as the plan to operate the facility as a locally managed museum was incurring unsustainable debts. Donald Sobey, chair of the Friends group, explained that the restructuring process would “maximize cost efficiencies, secure additional funding for new exhibits and provide a basis for long-term viability.”30 The plan was to solicit federal and provincial monies and supplement this with private donations. In June 1996, the Friends made an urgent request for a provincial loan of $300,000. This appeal was denied. Media reports noted ruefully that the government had decreed that Nova Scotia’s industrial heritage was not worth preserving.31 Interviews with museum director Debra McNabb and curator Peter Latta make clear the tenuous state of the project in its early years.32 The perseverance of the Museum of Industry is testament to the sheer tenacity of its dedicated staff and stalwart community support.

Only when the province reasserted direct control, and with the injection of further federal financial support, was the troubled venue’s future secured.33 The museum itself, with its anticipated jobs and the expected boost to local tourism, was advanced as a partial remedy to Pictou County’s economic malaise. With the announcement, politicians noted the museum’s importance to the regional economy and anticipated that the site would soon rival the Parks Canada national historic site at the Fortress of Louisbourg.34

The Museum of Industry opened with a modest initial display area covering the 19th century; a second permanent exhibition gallery, depicting industrialization from 1925 to the present, was later completed. Unlike other historical sites in Canada that adopted elements of the “living history” concept of museology dominant during the postwar decades – notably, Sherbrooke Village on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore – the new museum would avoid interpreters or reenactors. Visitors were be left to themselves to wander through permanent and temporary displays, read the accompanying descriptions, and draw from the experience what they would.35

Beyond the confines of the museum building, the exterior grounds included the relocated and partially restored 1860s stone structure of the Cornish mine pumphouse. As well, the Stellarton rail station remained as originally constructed on the periphery, near the location of the original Intercolonial Railway (icr). It was the icr that had provided the vital transportation link for the region to the rest of the nation and helped spur 19th-century development. Yet even as the first visitors toured the museum in the 1990s, the ironic disjuncture between the institution’s representation of the industrial past and the deindustrializing present was evident. The Albion Mine pumphouse was in imminent danger of demolition with the ongoing twinning of the Trans-Canada Highway, while the newly constructed Via Rail station was summarily abandoned because of the federal government’s decision to terminate passenger service to Cape Breton.36

Navigating the Contested Landscape of Memory

If one ventures beyond the museum and into the town of Stellarton, south along Foord Street in the heart of what was a community of modest employee houses, one comes across the Miners’ Memorial. Erected in 1921, the monument’s tall black granite column is topped with a statue of a coal miner. A standing miner also tops the nearby Westville icon, raised in 1891 to commemorate the Drummond Colliery explosion of 1873. On the Stellarton column are engraved the many names of those lost to the 1918 Allan Shaft explosion. To these have been added the names of those killed in other major calamities between 1880 and 1952. Then, as the surface of the column itself was filled, the names of the victims of the 1992 Westray explosion were cut into the base. Accounting for smaller incidents, the toll extracted for coal in Pictou County is approximately 600. Annual commemorations are held in Stellarton to coincide with Davis Day (Miners’ Memorial Day) events in New Waterford, Cape Breton, which observes the 1925 struggle against the British Empire Steel Corporation.37 The Stellarton and Westville markers were erected not by entrepreneurs or civic officials but by the miners themselves. These sentinels, while lacking the visual and narrative details of a museum display, have greater gravitas as the messages are of mutual loss combined with the heroic determination of miners and their communities. They tell an oft repeated story of an avoidable sacrifice of men and boys to a known threat of explosive methane gas and coal dust that employers and government officials ignored repeatedly.38

Miners’ Monument, Stellarton, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

Travelling an almost equivalent distance northward from the museum, a visitor would discover a very different memorial: Sobeys Industrial Monument in New Glasgow. Situated on the front lawn of the Sobeys headquarters on Foord Street – a roadway named after the gaseous coal seam that was mined for generations – the small red brick edifice takes the shape of a factory and is framed by a smokestack at either side and crowned with a mine headframe. The face of the structure has granite panels depicting the Samson locomotive, the Cornish Pump at the Foord Pithead, and the Allan Shaft. An accompanying map situates this industrial legacy from 1839 up to the contemporary era. The message is explicitly progressive. Sobeys and its parent entity, Empire Corporation, are inheritors of a continuing tradition of economic development: “Today at this historic place, as we move forward, the descendants of bygone workers uphold the enterprising legacy of their forebears in a modern industry that embraces leading technology to prosper and grow.”

Sobeys Industrial Monument, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

The Miners’ Memorial and the Industrial Monument are like magnetic poles that the Museum of Industry navigates between as it represents the region’s industrial heritage to visitors. The tragedies of the industrial past can hardly be ignored. The cumulative suffering of coal miners and their families is a thread that runs throughout the museum displays, but the dimensions of class resistance remain understated to the point of obscurity.39 This restricts the range of interpretative potential to one of the sadness or resignation in response to industrial fatalities and fails to acknowledge the anger and defiance of generations of miners who joined unions demanding improved pay and working conditions. The melancholy is tempered by repeated returns to the refrain of the Sobeys memorial insisting that the “enterprising legacy” be upheld in the present and future.

The balancing act of the museum’s displays is also evident in their engagement with historical explanations of industrial decline. The economic challenges facing the region are hardly new. Reporting on the postwar national economy, Maclean’s columnist Blair Fraser noted that the “cold smokestacks at Trenton, the silent shipyard at Pictou” signalled a return to the harsh regional austerity that had beleaguered the Maritimes for decades. Despite unprecedented federal government investment during World War II, and the short-term bump of military service bonuses from the Veteran’s Charter, dire unemployment persisted in northeastern Nova Scotia. “On paper,” Fraser emphasized, “it is worst in Pictou County, where some plants have shut down altogether. In November [1946] New Glasgow had 2,300 unplaced applicants and exactly 23 unfilled jobs.”40

In his much-cited analysis “Consolidating Disparity,” E.R. Forbes argues that the war brought only transitory economic benefits and the conversion to peacetime served to further disadvantage the Maritimes, as central Canada benefited from substantial federal infrastructure renewal that accelerated the rapid transition of industrial modernization. Forbes notes that this was due more to political neglect than market logic, which led to the “classic interpretation of the decline of manufacturing in the Maritimes as the inevitable result of economies of scale and agglomeration in Central Canada.”41

Following Forbes, theories of dependent development have been applied to Nova Scotia, and notably to Pictou County, to analyze the consequences of the original 19th-century National Policy and subsequent phases of industrialization and deindustrialization. The research of Anders Sandberg notes that Canada’s first steel mill was established by Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Corporation (scotia), first in New Glasgow by 1883, and later at Trenton. Integrated coal and iron ore mining, steel production, and transportation were all well advanced by the turn of the 20th century. Following the 1921 sale of scotia to the notorious British Empire Coal and Steel Corporation (besco), a pattern of neglect and disinvestment disadvantaged Pictou County for generations.42 For Sandberg, the eventual decline and failure of extractive and heavy manufacturing industries was a consequence of the lack of managerial and political control in the Maritimes. Sandberg’s analysis was challenged by Larry McCann, who maintained that the Maritime-based coal and steel sectors were destined to fail given both the region’s location on the periphery of North American markets and alternatives in central Canada.43 Meanwhile, historians focusing on class analysis of the region argue that coal miners and steel workers had a rich tradition of self-organization through unions and other fraternal institutions and always resisted the exploitation by corporations and governments.44

As the Museum of Industry started to take shape, both the collected artifacts and interpretive materials presented to visitors would straddle the divide between suggesting that Pictou County had historically suffered from dependent development and championing the entrepreneurial record of regional industrialization. While unions are mentioned as organizations that historically advocated for better workplace conditions, there is scant inference of the crucial way in which organized labour and socialist ideology framed the everyday lives of industrialized Nova Scotia and formulated a powerful critique of capitalist exploitation.

Blood on the Coal

As the Museum of Industry was being developed, plans included re-exposing the area’s industrial archaeology. Trained personnel were brought in to map and excavate the original 1827 foundations and artifacts.45 These abandoned structures would be identified on the same grounds that held the unrecovered buried remains of miners killed in earlier Albion Mines tragedies, a disconcerting reminder that there had long been “blood on the coal.”

Coal mining occupies a special place in the historical memory of Pictou County. The physical challenges and dangers of the occupation, the exploitative conditions below and above ground, and the comradery and solidarity of mining unions form a compelling narrative with vivid detail. The sections of the museum dedicated to the miners, their families, and the communities are the most evocative in the facility. Reinforcing some of the interpretations of the Glace Bay Miners Museum in Industrial Cape Breton and the Springhill Coal Mining National Historic Site of Canada (the Cumberland County coalfields site of multiple disasters), the permanent gallery effectively combines mining artifacts and oral history to provide visitors with a synopsis of the “men of the deeps.” The narrative of overcoming hardship and of hardworking production mesh well with contemporary tropes that suggest Pictou County, and Nova Scotia, were “open for business” – supplied with an eager workforce and favourable tax structures.

The Museum of Industry portrays the work of miners and steelworkers as providing the necessary brute physical backbone of these rugged and dangerous occupations, but this acknowledgement is framed as the “blood and valour” of heroic sacrifice and not the exploitation of capitalism. Mounted on one wall of the permanent miners’ exhibit “Coal and Grit” is a wooden plaque with the title “Honor Roll,” memorializing over 150 men and boys whose lives were lost to pit accidents in the Acadia Mines between approximately 1917 and 1969. Beyond the obvious interpretation that coal mining is inherently dangerous, it is unclear whether visitors to the museum will recognize that many of these “accidents” may have been preventable if not for the collusion of financiers, mine operators, politicians, and government officials. That these names were not lost, and that the Westray story would add to this misery, suggests not a denial of the technical risks in the museum’s narrative but a suppression of the analysis that generations of industrialization were advanced in the absence of alternative employment.

At the museum, the coal mining interpretative panels note the 1826 arrival of the General Mining Association, stating that “on this spot, the future came to Nova Scotia.”46 The future has long been promised to Nova Scotians by successive waves of forward-looking optimists. This future focus has had the effect of actively obscuring the past – a past that, while not forgotten at the museum, is now desiccated to render it safe for nostalgia. That the museum opened to the public only three years after the disaster at the Westray Mine suggests just how present the past of mining tragedy could be and how bleak the promised future of 1826 would be for mining families.

From the day of its opening, the Museum of Industry has always included physical and online exhibits dedicated to Westray amid its broader history of coal mining in mainland Nova Scotia. Augmenting the museum-based experience, online links to the “Coal and Grit” presentations include multiple avenues to learn more about mining disasters and government investigations.47 An expanded 2017 exhibit once again foregrounded the Westray tragedy. However, tensions remain between academics and museum professionals as to how to best convey the consequences of industrialization/deindustrialization.

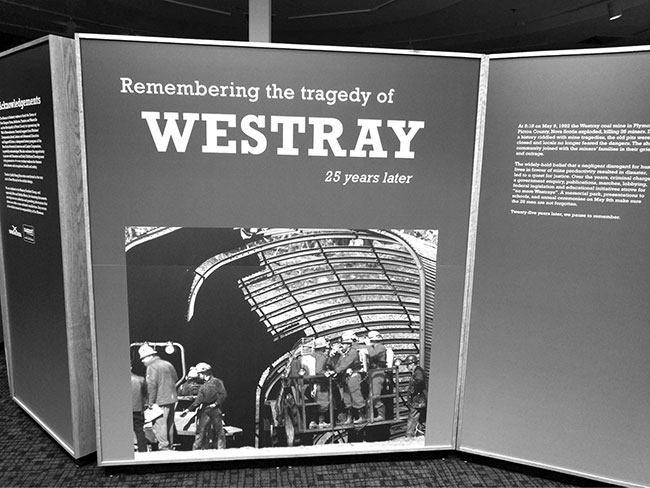

April 2017 marked the grim 25th anniversary of the Westray Mine explosion that killed 26 men and dealt a severe blow to the underground coal industry and the broader economic prospects for northeastern Nova Scotia. Westray was from its inception wracked with controversy in an area notorious for the dangerous presence of methane gas. The mine was something of a desperate effort to reinvigorate the stagnant coal sector and provide economic sustenance to a regional economy suffering severely from 40 years of uneven economic development schemes and from broader vulnerabilities of a peripheral region in a have-not province.

Westray was a mine that should never have been built, but when the decision was made to proceed, the workers and their community could have been protected by existing mine safety regulations – yet they were not. Enticed to the region by the offer of jobs, many miners were hardrock experienced and had less practical job experience with the gaseous threat of Pictou County’s methane. The systemic failure of the protections that were in place led directly to an explosion predicted by many – what has been termed “death by consensus.”48 The minute details of serial failures and betrayals by the mine owners, federal and provincial politicians, and health and safely inspectors, among others, form the voluminous body of critical literature on Westray.

The loss of lives and economic potential deeply affected Pictou County, and the portrayal of this history remains a sensitive matter for the Museum of Industry. There is a disjuncture between the twin threads of honouring the 26 lives lost and acknowledging their affected families and also sustaining the public outrage over an industrial accident that was so clearly avoidable. The question was always about how the museum dare tread in this contested terrain of memory and commemoration. Its 2017 display opted for the reverential over the political, and in so doing, centred on the implicit narrative that bad things happen to good people. Those with a cursory knowledge of the disaster will recall that the Westray Mine was not unionized; an attempt by the United Mineworkers of America was countered by intimidation from mine management. A subsequent drive by the United Steelworkers of America did garner sufficient signatures, but only after the explosion had ended production. Of the visual images on display for the 25th anniversary, only a single photograph included a (partially obscured) Steelworker flag. In a facility dedicated to the province’s ongoing struggle with industrialization, the absence of labour’s resistance to exploitation results in the social construction of a limited truth that has been termed “states of denial.”49 Context is crucial to understanding – and here that context was the willingness of the provincial and local governments to invest in a mining corporation, such as Curragh Resources, with a poor safety record.50 This context is not emphasized in the Museum of Industry.

The concrete silos of the Westray Mine remained for some time after operations ceased, their distinctive blue tops visible from the nearby highway and from the museum. The eventual removal of this tragic landmark was less an act of historical cleansing than one of gentrification, as this land would never be repurposed. The erasure of the physical structures at the Westray site redirects historical commemoration to sites like the museum, where the emphasis is on the loss of the miners instead of on the negligence that resulted in a project that should have never been given the green light to proceed. Those wishing to learn of Westray may visit the museum exhibit or the nearby black granite stone with the miners’ lamp shining on the names of the dead, but the precise location of the explosion is gradually obscured as the cleansed landscape is retaken by nature. The inclusion of a single miner’s helmet encased in a plexiglass display redirects focus to the individual loss of life and away from collective efforts to unionize this workplace and to hold both the employer and the provincial government accountable for repeated safety violations.

Westray 25th Anniversary exhibit, Museum of Industry, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

The museum’s respect for the Westray miners has become a synecdoche for the hundreds of miners killed and injured since the early 19th century, and the museum does well to convey this appreciation. Subterranean coal mining, especially in the methane gas–laden mines of the Foord seam, was an inherently dangerous occupation. Heroic miners and their stalwart families are offered up in a depiction that follows a similar redemption trope for mining communities, including the 1958 Springhill “bump.”51 While thanks and praise are offered to those freed from death below, and solemn remembrances to those less lucky, less open for discussion is the question of why people found themselves in such perilous circumstances. The Museum of Industry, while acknowledging decades of communal suffering wrought by the pursuit of coal, does not sway from the broader narrative that such economic ventures were both inevitable and desirable. Past losses are never forgotten but remain subservient to the message of progress.

Remembering Postwar Decline

The North American drift away from heavy industry and manufacturing has accelerated since the 1980s with the advent of international agreements such as the Free Trade Agreement (fta) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (nafta) and the global embrace of neoliberal austerity. In Nova Scotia, redundant factory sites sought to quickly rid themselves of the detritus of past operations, and in the rush to divest, everything from machinery to personnel records were subject to disposal in what might be termed wanton acts of memory erasure. Only the timely interventions by the Museum of Industry and other curators salvaged a small portion of these materials.

Museum employees were often called out to scavenge from the demolition sites of abandoned factories or take custody of company records deemed expendable. When the nearby Trenton Steel Works, manufacturers of rail cars with origins dating to the 19th century, underwent a transition in corporate ownership and summarily discarded boxes of employee files and production designs, some of these files were eventually accessioned by the Dalhousie University Archives.52 The new, American-based owner, Greenbriar Companies, later donated the massive axle forging hammer and anvil in anticipation of relocating manufacturing to Mexico. The Museum of Industry thus added another artifact of Pictou County’s rapidly deindustrializing landscape as the Trenton Works ceased 135 years of steel fabrication.53 The case for the museum seemed evident: the region’s industrial heritage was rapidly vanishing and there was an urgent need for a suitable repository.

In 1948, a federal Department of Labour survey rated Pictou County alongside Industrial Cape Breton as having the worst unemployment in the nation. The rapid decline in coal production left the province’s economy reeling. By the late 1950s, all but one of Pictou County’s twelve mines were closed permanently.54 This postwar economic decay quickly became the subject of intense scrutiny, with the federal government commissioning studies to develop a way forward.55 If coal was no longer king, then the economy would need to diversify. To this end, the provincial Conservatives under Robert Stanfield established Industrial Estates Limited (iel) in 1957 as a Crown corporation with a mandate to bring international investors to Nova Scotia.56

This project of state-sponsored industrialization reached its apogee in the 1960s, only to fail to secure long-term economic stability. The government of Canada had expanded regional development schemes by 1960 with a series of agencies focused on stimulating investment.57 At the Museum of Industry, the display covering the postwar era includes a contemporary poster touting that Nova Scotia was “Looking Ahead” and had “Plans for Tomorrow.” An accompanying panel explains how various schemes to expand the manufacturing bases had met with limited success in staunching the industrial decline of the first half of the 20th century. This ambivalent celebration of progress is advanced with indirect reference to complaints that the Maritimes had not benefited sufficiently from federal investment during World War II.

Michelin Man exhibit, Museum of Industry, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

Another notable attempt at economic diversification enticed the French multinational Michelin Tire to establish three manufacturing plants in the province. Despite ongoing tax subsidies, and the passage in 1979 of the notorious anti-labour “Michelin Bill” that effectively thwarted several campaigns for union certification, the province struggled to ensure employment stability. The 46-year-old Granton plant in Pictou County reduced production in 2014, eliminating 500 jobs.58 The museum presents Michelin’s identity as much less problematic: the corporate brand is celebrated, replete with an oversized image of the “Michelin Man” and a giant truck tire swing on which visitors may sway. Despite following the example of many international corporations and pulling jobs from Pictou County, the public history of Michelin as presented in the museum remains upbeat. Local visitors, one presumes, are encouraged to be thankful for the jobs once provided and the residual work that remains.59

The patterns and problems of representing the postwar industrial story at the Museum of Industry are also evident in its treatment of the Clairtone Sound Corporation. Clairtone was established in 1958 by Toronto-based entrepreneurs Peter Munk and David Gilmour. From its start as a small manufacturer of high-end audio units, the company expanded rapidly. Its iconic Project G stereophonic system, with its sleek wooden console bracketed by distinctive black globe-shaped speakers, became a 1960s status symbol. Ambition soon overtook a reasonable business plan. In 1964, Clairtone was enticed to relocate to Stellarton with funding supplied by iel. The Crown corporation itself was supported through larger regional development authorities established by the federal government to support provinces that were falling behind in economic expansion. Despite stagnant sales of its stereophonic units, Clairtone expanded into the production of early colour televisions, the high list price of which was beyond the means of most consumers.

Following the lead of iel president (and former Stellarton mayor) Frank H. Sobey, the corporation aggressively recruited Canadian and foreign investments to Nova Scotia. Clairtone was offered $8 million in start-up funds, tax concessions, and the promise of workforce training.60 The substantial 250,000-square-foot plant, to be situated on land outside the town, was to hire and train at least 550 local employees. Clairtone imported advanced German woodworking technology and initiated a sophisticated vertically integrated production line.61 For the grand opening of the facility in June 1966, invited guests were flown from Toronto on a charted aircraft and then conveyed to Stellarton on a special train. At the event, attended by Premier Stanfield and federal minister John Turner, Munk boldly proclaimed, “Sir, we will not let you down. We shall be in the forefront of your industrial revolution.”62 Once again, Pictou County sought to join the leading edge of another industrial revolution only to discover that the moment was all too fleeting.

Despite this auspicious beginning, Clairtone soon experienced major logistical problems with both importing components and shipping completed units. The risks of situating on the periphery of the North American consumer market came to haunt the fledgling operation. By 1967, Clairtone was falling behind in its production schedule and iel moved to isolate both Munk and Gilmour from active decision-making. At the end of that year, both men were reduced to nominal directors, and by 1968, they were mere outside consultants of the corporation they had founded. An ill-advised move to assemble televisions had consistently failed to meet targets, while the stereo consoles remained priced out of reach of most consumers. Overburdened with debt, iel ceased all production in 1970.63 Despite efforts to repurpose woodworking machinery to manufacture coffins, the Clairtone facility remained untenable and the estimated $25 million provincial investment was written off.64

Peter Munk later charged that Clairtone employees had been part of the problem: “The general population is not geared to the manufacturing frenzy and the five-day work week. The welfare situation is such that it has created conditions similar to Appalachia in the United States, where the third generation is already on relief.”65 Despite such disparagement, workers flocking to Clairtone had envisioned secure industrial jobs in a region badly in need of stability. Munk left to pursue other ventures and, in time, through business interests in Trizec Properties and Barrick Gold, became a billionaire and widely influential philanthropist. Gilmour would similarly enjoy success in real estate and other ventures.66

In 2016, the Museum of Industry mounted a special exhibit to commemorate 50 years since the opening of the Clairtone factory in Stellarton. “Glamour + Labour: Clairtone in Nova Scotia” was an upbeat celebration of the all-too-brief fling with 1960s style and economic opportunity.67 The exhibit provided the opportunity for visitors to take images of themselves alongside the Project G stereo console and Clairtone television sets. Visitors could pose for pictures while sitting at a reconstructed factory assembly table and remember the Clairtone years. Reflecting on this moment, former Conservative premier John Hamm, who briefly served as factory physician, described the experience in thoroughly positive terms. “It was,” he noted, “a magical time for us here in Stellarton.”68 Yet Dr. Hamm, as a middle-class professional, could move on to other ventures while most in Pictou County were faced with limited options. Scanning 1966 photographs of the Clairtone employee parking lot reveals an abundance of automobiles whose model years well predated the swinging ’60s. It was obvious that people needed jobs, and they needed this work to last beyond the tumultuous years of Clairtone.

The Clairtone exhibit, later made a permanent feature of the museum, interprets the story as one of optimism and defeat. This contested industrial heritage is repackaged as community solidarity and persistence, when an alternative reading might suggest that the region was buffeted by a combination of transient capital investment and political ineptitude. Panels of photographs show the gleaming Clairtone factory and busy assembly lines. A top-of-the-line Project G stereo system and advanced g-tv colour set feature prominently in the exhibit, suggesting that Stellarton once stood proudly at the forefront of consumer electronics. This even though few, if any, from Pictou County could ever afford such extravagance.

Less emphasized was the frustration of broken promises, the economic crises and emotional emptiness, attendant with such spectacular failure. Expunged from the display are comments that deprecated the local workforce as being unmotivated and ill suited to the electronics industry. Was this an act of erasure, or are alternative understandings available? Were former Clairtone workers and their descendants collectively refusing to accept the characterization that the community was a “backwater” imbued with a culture of defeatism, suggesting that the enterprise was good while it lasted, things change, and progress marches ahead? If so, as an exercise in the cultural agency of this working-class community, the push-back was laudable. The question arises, however, as to whether the museum’s representation of the Clairtone narrative limits the possibilities for an analysis that would situate it within the broader legacy of entities like iel that sought to cultivate hothouse regional development and significantly failed to achieve the reindustrialization of Pictou County.69

Peter Munk on a Clairtone TV, Museum of Industry, Nova Scotia.

Photo by the author.

Another legacy of 1960s-era iel recruitment was the Scott Paper Company pulp and paper mill at Abercrombie Point, site of the original 1830s railroad coal shuttle that brought the Sampson and Albion locomotives to Nova Scotia. The venture was first announced in 1964 by Premier Stanfield as a “Christmas present” to the people of Pictou County, in reference to the prospects of generations of secure employment. However, the new mill quickly became embroiled in decades-long conflicts over severe air and water pollution. These battles pitted the local Mi’kmaq Pictou Landing First Nation and fishers against the powerful forestry sector and unionized employees at Scott Paper.70 Once again, the disjuncture between encouraging heavy industry and increasing post-industrial tourism was highlighted. The mill’s presence was unavoidable for tourists on the drive to the Caribou terminus of the ferry to Prince Edward Island. If Pictou County, and the Museum of Industry, sought to be part of the loop for vacationers travelling between Cape Breton and PEI, the Abercrombie Point mill remains a stark reminder of the dilemma of juggling competing economic sectors.

By 2017, Scott Paper’s intention to run an effluent pipe into the Northumberland Strait led to environmentalists’ chants of “No Pipe!” and the workers’ rejoinder, “No Pipe – No Mill.” The closure of another pulp and paper mill in Liverpool (on Nova Scotia’s South Shore) and the near-death experience of yet another at Point Tupper in Cape Breton attest to the challenges encountered in staving off deindustrialization. For decades, the Northern Pulp mill was notorious for its emission of caustic sulphur dioxide and serious pollution of the water at Boat Harbour (A’se’k), site of the plant’s residue treatment outflow that was undeniably the legacy of environmental racism toward the local Mi’kmaq.71

Such a divisive subject has been problematic for the Museum of Industry. The original operator, Scott Paper, is referenced in some documents held at the museum, but the more accessible visual displays have stood apart from the debate. The exception was the provocative 2014–15 photographic exhibit “Clean Air, A Basic Right,” which portrayed the significant effects of the toxic emissions from the pulp operations.72 This foray into the intensifying controversy returned the focus to issues of deindustrialization.

The only adequate solution to decades of water and air pollution was to shutter operations at Northern Pulp, thus compounding the already crushing local unemployment and economic despair. If the Abercrombie mill was closed permanently, the inevitable dismantling and removal of production machinery could be expected to occur along with general site remediation. With this, the physical, visual, and olfactory landmark of more than 50 years of heavy industry, with its close links to the forestry sector, would be rendered invisible.73 In the case of Northern Pulp, left remaining would be the mercury-laden sludge collected in Boat Harbour lagoon, a toxic dilemma similar to that of the Sydney tar ponds following the demolition of the steel mill.74

The twisting saga of Northern Pulp was heightened with the 2017 release of investigative journalist Joan Baxter’s book The Mill: Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest. The museum, to its credit, hosted a book signing on-site despite intense pressures by the company to cancel or boycott venues scheduled to publicize the book.75 With both the exhibit “Clean Air, A Basic Right,” and the decision to tacitly support the publicity of Baxter’s The Mill, the museum found itself navigating the intense public debate on deindustrialization and the future of Pictou County. The established presentation of underground coal mining and steel manufacturing as past industrial phases suddenly lurched into contemporary controversy. Heritage as uncontroversial, hermetically sealed historical segments gave way to divergent narratives of community economic survival versus an overdue recognition of past environmental and human rights abuses. As a site of knowledge production and interpretive opportunity, both the Museum of Industry’s exhibits and its physical premises were reappropriated from the expected narrative of quietly celebrating industrial progress to a component of a modern struggle for social justice. This may not have been the curatorial function that the Sobey family or the provincial government expected, but arguably it may have consolidated a more relevant ongoing role for the museum.

Selective Memories

The Nova Scotia Museum of Industry remains a notable experiment in the provincial system of 28 facilities and historic sites. Always something of an outlier, the museum continues to program limited temporary exhibitions while maintaining its core collection. Visitors to the museum gain appreciation of the past in terms of the fraught cycle of industrial expansion and contraction. The ongoing project has been a collective passion for the museum’s staff and many volunteers over several decades and should be respectfully acknowledged. However, the narrative that frames this collection is not the only possible interpretation of the area’s industrial past. The narrative includes the claim that Pictou County and Nova Scotia were once on the leading edge of industrialization in British North America. That these industrial pursuits – coal mining, steel making, and others – would ultimately fail over time would not be attributable to lack of determination or commitment.76

The museum’s directive is to educate patrons, especially schoolchildren, that their region did once, and may still, offer a promise of successful economic livelihood to counteract the impetus for “goin’ down the road” to seek better opportunities.77 For those rushing by various displays and museum sections, the message is often one of progress – not without its setbacks and challenges, but continued faith in progress. In 2009, the province issued an updated mandate for the Museum of Industry that acknowledged the region’s industrial plight. In a candid appraisal of the contemporary situation, the museum would in the future “provide explanations as to why Nova Scotia’s obvious industrial strength diminished over time, and the different initiatives taken to reverse this reality.”78 Such elucidation remains minimal, suggesting curatorial decisions to avoid more complex messaging over deindustrialization.

Historians have scrutinized a range of public museums and private theme parks that present an interpretation of nostalgia devoid of class strife or contradiction.79 Canadian history, and certainly Nova Scotia’s past, is replete with examples of intense social conflict directly related to industrialization. Pictou County and the surrounding coal towns were, at times, split with class tensions. Industrial Cape Breton, with its protracted “coal wars” of the 1920s, had the province invoke “military aid to the civic power” measures and transport the Canadian Army to enforce martial law in Sydney.80 The larger-than-life personalities of union leaders J. B. McLachlan and “Red” Dan Livingstone were well known in the Pictou region. Coal mining communities often sang “The International” or “The Red Flag” during annual May Day celebrations.81 For a province that was once the single largest producer of Canadian coal, and a region that produced an active union movement, the museum’s understated recognition of trade unions is notable. The striking absence of any meaningful class analysis is telling in terms of the museum’s purpose and the interests of some of its most powerful supporters.

On one level, the museum succeeds in its mandate to collect and display this vanished past. The collection is displayed according to the standards of the museum profession, and the original physical structure continues as a venue for sporadic exhibitions. While the museum’s potential to attract seasonal tourists never developed to the extent envisioned in the 1984 Lord Report, the operation persists. Successive cohorts of schoolchildren have been duly led through the permanent exhibits in the hope they will retain some semblance of knowledge as to the industrial heritage of this place. Yet anecdotal evidence suggests that many locals who worked in the industrial ventures highlighted in the displays rarely enter the Museum of Industry. The moniker “museum of industry” is a depressing reminder that scant industry remains. Whether for Michelin employees, former coal miners, or unemployed call-centre workers, the museum implicitly speaks of the inevitability of industrial decline and the broadly accepted imperative to move forward in an economy that is simultaneously intensely localized and reluctantly global. Its permanent displays and temporary exhibits repeat the refrain that upbeat and positive adherence to “progress” will convey the province onward to the next big venture. The museum display “A Century of Change: Nova Scotians Rise to the Challenge” promises that this region will “remain competitive” in the struggle to withstand the buffeting forces of global capitalism.

Museum exhibits evoke expectations of capitalist initiative and revival that, in the case of Pictou County and northeastern Nova Scotia, has never been fully achieved. It offers a vision of what the surrounding towns thought they might become in a sincere projection of civic boosterism, only to treasure a collection of half-realized plans overwhelmed by stagnation and decline. It is a monument to residual industrialization – a mausoleum of curated decay. Despite Nova Scotia’s proud heritage of worker resistance and union activism, visitors may leave the Museum of Industry with the message that the story of working-class lives, while worthy of sombre reflection, must give way to inevitable advances of a modern post-industrial society. To this nostalgia of forgetting, however, there may erupt sporadic moments, such as the Northern Pulp controversy, when museums may assume dynamic roles in contemporary social debate.

1. The contrived antimodern image of the province is critiqued in Ian McKay, The Quest of the Folk (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1984); Ian McKay and Robin Bates, In the Province of History: The Making of the Public Past in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010): Meaghan Beaton and Del Muise, “The Canso Causeway: Tartan Tourism, Industrial Development, and the Promise of Progress for Cape Breton,” Acadiensis 37 (Summer/Autumn 2008): 39–69.

2. While deindustrialization has garnered significant scholarly attention, less of a focus has been on the consequences for rural economies less reliant on a single industry or company town. The Canadian literature on deindustrialization is extensive and includes Lachlan MacKinnon, Closing Sysco: Industrial Decline in Atlantic Canada’s Steel City (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020); Steven High, One Job Town: Work, Belonging, and Betrayal in Northern Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018); High, “Beyond Aesthetics: Visibility and Invisibility in the Aftermath of Deindustrialization,” International Labor and Working-Class History 84 (Fall 2013): 140–153; High, “‘The Wounds of Class’: A Historiographical Reflection on the Study of Deindustrialization, 1973–2013,” History Compass 11, 11 (2013): 994–1007; High, “The Politics and Memory of Deindustrialization in Canada,” Urban History Review 35, 2 (2007): 2–13. The Canadian and international contexts are addressed in Steven High, Lachlan MacKinnon, and Andrew Perchard, eds., The Deindustrialized World: Confronting Ruination in Postindustrial Places (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2017); Ewan Gibbs, Coal Country: The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland (London: University of London Press, 2021).

3. Internationally, there are several museums whose primary focus is on machines and invention. A partial list would include the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester; the Rhineland Museum of Industry in Oberhausen, Germany; the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago; the Baltimore Museum of Industry; the National Museum of Industrial History in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; and the Toyota Commemorative Museum of Industry and Technology in Nagoya, Japan. Smaller museums include the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation in Waltham, Massachusetts; the American Precision Museum, Windsor, Vermont; the Museum of Bath at Work in Bath, England; and the Workers Arts and Heritage Museum in Hamilton, Ontario. See also Steven High and Fred Burrill, “Industrial Heritage as an Agent of Gentrification,” History@Work blog, National Council on Public History, 19 February 2018, http://ncph.org/history-at-work/.

4. The initial Proposal to Study the Establishment of a Museum of Transportation and Technology in Nova Scotia was pitched to the Nova Scotia Museum complex. In 1976, the Committee for Preservation of Mining Heritage was established, which coincided with a two-volume proposal for the Stellarton museum commissioned by the Nova Scotia Museum system: Duffus, Romans, Kundzins, Roundsfell Ltd., Study for a Museum of Transportation and Industry (Halifax: Nova Scotia Museum, 1976). The pre-existing Stellarton Miners’ Museum transferred its holdings and closed with the creation of the museum. For details on the Sobey corporate legacy, see Harry Bruce, Frank Sobey: The Man and the Empire (Toronto: MacMillan, 1985); Eleanor O’Donnell MacLean, Leading the Way: An Unauthorized Guide to the Sobey Empire (Halifax: gatt-fly Atlantic, 1985).

5. David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 1–30; 127-147.

6. Interdisciplinary academic interest in deindustrialization, public history, and civic commemorations has spawned extensive published literature. Much of this work has examined the economic and social costs of dramatic industrial change in the primary resource sector and secondary manufacturing, notably the closure of factories in single-industry towns. Scholars have documented the emotional scars wrought by economic atrophy and the long-term ramifications for future generations. See, for example, Steven High, Industrial Sunset: The Making of North America’s Rust Belt, 1969–1984 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003); Stephen P. Dandaneau, A Town Abandoned: Flint, Michigan, Confronts Deindustrialization (Albany: suny Press, 1996). A broader analysis includes Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010); Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2010).

7. Peter Thompson, Nights below Foord Street: Literature and Popular Culture in Postindustrial Nova Scotia (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), 54.

8. Lianne McTavish, Voluntary Detours: Small-Town and Rural Museums in Alberta (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), 142–173.

9. Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London: Routledge, 1995).

10. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 44–55. In his discussions of the Ruhr Valley in Germany, Stefan Berger also observes that nostalgia has multiple iterations, from negative connotations of loss to positive framing that seeks to recuperate realistic understanding of working-class experiences. The ambitious projects Berger describes at the unesco World Heritage Site of Zeche Zollverein in Essen, Germany, suggests that public appreciation of deindustrialized spaces in the Ruhr Valley may be achieved with sufficient initiative and resources. Somewhat similar efforts to refute simplistic notions of meritocracy, and the implied obscurity of a disappearing working class, also feature in Steven High’s analysis of deindustrializing Montréal. The complexities of Essen and Montréal may not track directly to the modest objectives of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry, yet they illustrate, by contrast, the necessity of fully appreciating a working-class contribution as much more than a transient phase in a relentless go-forward message of provincial heritage. See Berger, “Industrial Heritage and the Ambiguities of Nostalgia for an Industrial Past in the Ruhr Valley, Germany,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History 16, 1 (2019): 37–64; High, Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022), 319–330.

11. Boym, Future of Nostalgia, 42.

12. Sherry Lee Linkon, The Half-Life of Deindustrialization: Working-Class Writing about Economic Restructuring (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 1–20.

13. Doreen Massey, “Places and Their Pasts,” History Workshop Journal 39 (Spring 1995): 182–192.

14. Ernest R. Forbes, Challenging the Regional Stereotype: Essays on the 20th-Century Maritimes (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1989); James Candow, ed., Industry and Society in Nova Scotia: An Illustrated History (Halifax: Fernwood, 2001); Margaret R. Conrad and James K. Hiller, Atlantic Canada: A History, 3rd ed. (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2015), 238–255.

15. Craig Heron notes that while museums and heritage sites typically make such images a central part of their exhibition practice, they are often presented without critical engagement of their history as artifacts. In Hamilton, Ontario, the Workers Arts and Heritage Centre serves as an example of the delicate balance to be achieved in the presentation of visual images and the negotiations between academic and public histories. See Heron, Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-Class History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 523–550.

16. As James E. Young writes, “the initial impulse to memorialize events ... may actually spring from an opposite and equal desire to forget them.” Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 5.

17. O’Donnell Maclean, Leading the Way, 5, 23–48.

18. Most of Sobeys’ retail businesses are non-unionized. The parent Empire Company Limited reported $30.5 billion in annual sales as of December 2022, and the company (including subsidiaries, franchisees, and affiliates) has roughly 130,000 employees. “Financial Highlights,” Empire Company Limited website, accessed 8 December 2022, https://www.empireco.ca/financial-highlights.

19. Marilyn Gerriets, “The Impact of the General Mining Association on the Coal Industry of Nova Scotia, 1826–1850,” Acadiensis 21, 1 (Autumn 1991): 54–84; Del Muise, “The General Mining Association and Nova Scotia’s Coal,” Bulletin of Canadian Studies 6, 7 (1983): 71–87. The Samson (1838) was built in Durham, England, by Timothy Hackworth. The museum prospectus claims that the locomotives, in service to haul coal ten kilometres from Stellarton to Dunbar Point, served as the first industrial railroad in British North America. In co-operation with the Scotian Railroad Society, three additional locomotives dating from the 20th century would be loaned to the Museum by R.C. Tibbetts. See “Locomotives,” Museum of Industry, accessed 8 December 2022, https://museumofindustry..ca/collections-research/locomotives.

20. Proposal to Study the Establishment of a Museum of Transportation and Technology in Nova Scotia, unpublished report presented to the Governors of the Nova Scotia Museum, 1974.

21. The Government of Canada established the Museums Assistance Program (map) in 1972. Other federal monies came from Department of Regional Industrial Expansion (drie) and Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (acoa). This was a legacy of the expansive Pierre Trudeau Liberals and would be drawn down by subsequent governments. See also Susan Whiteside, “A Brief History of the Nova Scotia Museum” (Halifax, 1987).

22. Barry Lord and Gail Dexter Lord, Nova Scotia’s Museum of Industry: A Plan for Implementation (Halifax: Nova Scotia Museum, 1984). See also Canada, Heritage Services, Heritage Policy Branch, “Terms of Reference: A Museum of Industry and Transportation,” in Museum Development Planning Information, 7 November 1983; Government of Nova Scotia, Department of Development, Policy and Planning Division, Museum of Industry: Economic Impact Study (Halifax, 1984); Catherine L. Arseneau, “The Origins and Early Development of the Nova Scotia Museum, 1868–1940 (ma thesis, Saint Mary’s University, 1994).

23. Lord and Lord, Nova Scotia’s Museum of Industry, 68.

24. This reading was consistent with Barry Lord’s class-conscious sympathies reflected in his works such as The History of Painting in Canada: Toward a People’s Art (Toronto: nc Press, 1974).

25. The Glace Bay facility was opened to the public in 1967. See Meaghan E. Beaton, The Centennial Cure: Commemoration, Identity and Cultural Capital in Nova Scotia during Canada’s 1967 Centennial Celebrations (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017).

26. William Sobey, “The Story of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry,” Pictou Advocate, 23 February 1988.

27. D.W. MacDonald (Executive Council of Nova Scotia) to J. MacEachern, memo, 5 November 1993, Nova Scotia Archives. The curatorial collection now exceeds 35,000 items, many of which are unique. See also Peter Clancy, James Bickerton, Rodney Haddow, and Ian Stewart, The Savage Years: The Perils of Reinventing Government in Nova Scotia (Halifax: Formac, 2000).

28. Friends of ns Museum of Industry contract to locally manage the museum, 1994, Museum of Industry Library files. In the end, little corporate funding was offered. The political infighting prior to the museum opening is addressed in Susan Parker, “An Industrial Museum in the Heart of Tartanism: The Creation of the Nova Scotia Museum on Industry,” ma thesis, Saint Mary’s University, 2018, 78–97.

29. Robyn Gillam, Hall of Mirrors: Museums and the Canadian Public (Banff: Banff Centre Press, 2001), 69–99.

30. “Museum Workers Face Three-Month Layoff,” New Glasgow Evening News, 27 January 1996.

31. “Let’s Save the Museum,” Daily News (Halifax), 15 June 1996.

32. Debra McNabb and Peter Latta, interview by the author, 31 August 2015; Debra McNabb, interview by the author, 10 September 2015.

33. “Fact Sheet,” 10 June 1996, Nova Scotia Museum of Industry Library; “Memorandum of Agreement – Friends of the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry and the Province of Nova Scotia,” 21 June 1996. The Friends would remain a volunteer society for the benefit of the museum.

34. “Province Takes Over Stellarton Museum,” Daily News, 21 June 1996.

35. The “living history” concept itself has been increasingly questioned as being overly simplistic. See Alan Gordon, Time Travel: Tourism and the Rise of the Living History Museum in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2016): Viviane Gosselin and Phaedra Livingstone, eds., Museums and the Past: Constructing Historical Consciousness (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2016); Robert Summerby-Murray, “Interpreting Personalized Industrial Heritage in the Mining Towns of Cumberland County, Nova Scotia: Landscape Examples from Springhill and River Hebert,” Urban History Review 35, 2 (Spring 2007): 51–59.

36. In January 1990, via Rail announced a 55 per cent reduction in nationwide passenger service. This included the line to Cape Breton passing through Stellarton.

37. Lachlan MacKinnon, “Labour Landmarks in New Waterford: Collective Memory in a Cape Breton Coal Town.” Acadiensis 42, 2 (Summer/Autumn 2013): 3–36.

38. For a discussion on the connections of landmarks and tragedy, see David Frank and Nicole Lang, Labour Landmarks in New Brunswick (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2010).

39. Judith Hoegg Ryan, Coal in Our Blood: 200 Years of Coal Mining in Nova Scotia’s Pictou County (Halifax: Formac, 1992).

40. Blair Fraser, “Men by the Sea,” Maclean’s Magazine, 15 February 1947.

41. Ernest R. Forbes, “Consolidating Disparity: The Maritimes and Industrialization of Canada during the Second World War,” Acadiensis 15, 2 (1986): 3–27, 26.

42. L. Anders Sandberg, “Dependent Development, Labour and the Trenton Steel Works, Nova Scotia, c.1900–1943,” Labour/Le Travail 27 (1991): 127–162.

43. L.D. McCann, “Space and Capital in Industrial Decline: The Case of Nova Scotia Steel,” Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire urbaine 23, 1 (1994): 55–57. doi:10.7202/1016698ar.

44. David Frank, J.B. McLachlan: A Biography (Toronto: Lorimer, 1999), 89–127, 133–175; Ian McKay, “A Note on ‘Region’ in Writing the History of Atlantic Canada,” Acadiensis 29, 2 (Spring 2000): 89–101; McKay, ed., For a Working-Class Culture in Canada: A Selection of Colin McKay’s Writings on Sociology and Political Economy, 1897–1939 (St. John’s: Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1996).

45. On colonial initiatives to spur early industries, see Daniel Samson, The Spirit of Industry and Improvement: Liberal Government and Rural Industrial Society, Nova Scotia, 1790–1862 (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008).

46. “Coal and Grit,” permanent display, upper gallery, Museum of Industry, Stellarton, Nova Scotia.