Labour / Le Travail

Issue 92 (2023)

Article

Waitresses in Action: Feminist Labour Protest in 1970s Ontario

Abstract: In the 1970s, women in Toronto created the Waitresses Action Committee to protest the introduction of a “differential” or lower minimum wage for wait staff serving alcohol. Their campaign was part of their broader feminist critique of women’s exploitation and the gendered and sexualized nature of waitressing. Influenced by their origins in the Wages for Housework campaign, they stressed the linkages between women’s unpaid work in the home and the workplace. Their campaign eschewed worksite organizing for an occupational mobilization outside of the established unions; they used petitions, publicity, and alliances with sympathizers to try to stop the rollback in their wages. They were successful in mobilizing support but not in altering the government’s decision. Nonetheless, their spirited campaign publicized new feminist perspectives on women’s gendered and sexualized labour, and it contributed to the ongoing labour feminist project of enhancing working-class women’s equality, dignity, and economic autonomy. An analysis of their mobilization also helps to enrich and complicate our understanding of labour and socialist feminism in this period.

Keywords: waitress organizing, second-wave feminism, Wages for Housework, minimum-wage laws

Résumé : Dans les années 1970, les femmes de Toronto ont créé le Waitresses Action Committee pour protester contre l’introduction d’un salaire minimum « différentiel » ou inférieur pour les serveurs servant de l’alcool. Leur campagne faisait partie de leur critique féministe plus large de l’exploitation des femmes et de la nature genrée et sexualisée de la serveuse. Influencées par leurs origines dans la campagne Wages for Housework, elles ont souligné les liens entre le travail non rémunéré des femmes à la maison et sur le lieu de travail. Leur campagne a évité l’organisation des chantiers pour une mobilisation professionnelle en dehors des syndicats établis; elles ont utilisé des pétitions, de la publicité et des alliances avec des sympathisants pour tenter d’arrêter la baisse de leurs salaires. Elles ont réussi à mobiliser un soutien, mais pas à modifier la décision du gouvernement. Néanmoins, leur campagne animée a fait connaître de nouvelles perspectives féministes sur le travail sexué et sexualisé des femmes, et elle a contribué au projet féministe syndical en cours visant à renforcer l’égalité, la dignité et l’autonomie économique des femmes de la classe ouvrière. L’analyse de leur mobilisation contribue également à enrichir et à compliquer notre compréhension du féminisme ouvrier et socialiste de cette période.

Mots clefs : syndicalisation des serveuses, féminisme de deuxième vague, salaire au travail ménager, lois sur le salaire minimum

Over the 20th century, waitressing became a well-established occupation for women, though they faced stringent prohibitions and regulations specifying if and where they could serve alcohol. When the last moralistic restrictions on their employment were removed in Ontario in the late 1960s and early 1970s, women had access to more bar and restaurant work, but they soon found their wages under attack.1 In 1975, a Conservative government implemented a lower minimum wage specifically for servers of alcohol, often referred to as the “tip differential.”

This minimum-wage rollback did not go unchallenged. The Waitresses Action Committee (wac) was founded in 1976 to stop its implementation and, in the process, offered a searing critique of the treatment of women service workers, particularly waitresses working in bars and restaurants. With its origins in the local Wages for Housework (wfh) campaign, the wac stressed the links between women’s unpaid domestic labour and their feminized workforce labour: “serving,” the committee wrote, is seen as “women’s work” that comes “naturally”; waitressing was perceived to be an extension of women’s private care for husbands, children, and friends and was thus undervalued, just as housework was.2 While the wac argued for a higher minimum for all servers, it concentrated its critique on the specific exploitation and oppression of waitresses. Though similar observations had been voiced in the history of waitress organizing, the wac enhanced and sharpened feminist perspectives on women’s gendered and sexualized service labour.

This article traces the wac’s origins in the Wages for Housework campaign, its understanding of women’s oppression, organizing strategies, and the successes and weaknesses of the tip differential campaign. Excavating the legacy of the wac reveals the necessity of posing questions about both the material context and the changing ideological forces that shape movements of resistance. The action committee’s existence owed much to the creeping austerity of the late 1970s and efforts by business and governments to reign in labour gains and social spending. Its development also reflected new feminist theories about sexual oppression that were emerging in the late 1960s and the 1970s, as well as a reinvigorated labour feminist project focused on advancing women’s equality, dignity, and economic autonomy.3

The wac’s brief life revealed the promise and the pitfalls of organizing women workers in this period. After the mid-1960s, women’s unionization increased significantly, as did their autonomous feminist organizing within unions; however, gains in the public sector outpaced those in expanding service, clerical, and personal work in the private sector.4 Organizing waitresses was difficult: only about 10 per cent of all servers in Canada were unionized, and most waitresses were spread across small workplaces, doing shift and part-time labour, moving in and out of jobs.5 A gender hierarchy within serving work consigned waitresses to lower-status venues and positions, with lower tips, leaving them especially reliant on a decent minimum wage and more vulnerable to employer pressure, harassment, and layoff. Their vulnerability was also related to expectations that they should “put out” extra emotional and sexual labour; depending on the serving environment, that could mean flirting or selling one’s body and attitude – “always acting compliant, gracious, coy [as if you are] sweet, smiling and pleasant by nature,” as Smile Honey, a wfh May Day pamphlet put it.6

The wac provides a small but significant window into the history of Canadian feminism and labour activism as intertwined movements, sometimes operating in productive alliance but also in tension, even in conflict. Indeed, the wac revealed a gap between some moribund trade unions and feminist organizing outside of them. Faced with some unions’ indifference, the wac sought support from feminists, sympathetic politicians, and social service, legal, labour, antipoverty, welfare rights, gay and lesbian, and immigrant groups. These endorsements were intended to bolster the committee’s anti–tip differential campaign, but the wac also sought political connections with groups similarly concerned with women’s low-wage labour, poverty, and oppression, including the “compulsory heterosexuality” associated with the patriarchal, nuclear family.7

The wac story also underscores the need for a critical perspective on the discourses that have defined feminist theory and activism. As feminist literary scholar Claire Hemmings shows, by the 1990s, one dominating narrative in feminist theoretical writing portrayed the 1970s – often referred to as a period of “second-wave” feminism – as a time of limited, narrow, “essentialist” feminist thought that was thankfully superseded by more progressive and inclusive feminist theories.8 The wac is one more challenge to this linear “progress” narrative. Labour historians have similarly challenged views of the 1970s as predominantly a time of retreat and retrenchment.9

Finally, the short-lived but vibrant wac reminds us how important it is to study history’s disappointments and lost causes. As E. P. Thompson suggested in a much-quoted passage, working-class history is enriched by an understanding of people and movements that failed, were replaced, or were overtaken by other movements. Locating fleeting labour and socialist feminist “histories from below” similarly offers insights into our understanding of capitalism and resistance to it.10 Despite the wac’s transitory existence, it nonetheless had an impact on feminist labour organizing, which was always a cumulative process of trial and error, of ideological insight and experimentation, of successes and failures, all of which inevitably left trace elements within the character of Canadian labour feminism.

Origins in Wages for Housework

The Waitresses Action Committee emerged from and remained linked to the Toronto wfh campaign, established in 1974, and its subgroup Wages Due Lesbians. Wages for Housework was associated primarily with a demand for wages for unpaid domestic labour, rather than workplace organizing; however, the wac’s existence underlines the range of wfh interests – beyond the demand for wages for housework – and the importance feminists attached to understanding the connection between paid and unpaid work. Without transforming both, they believed, emancipation was not possible.

Inspired initially by European activists Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James’ 1972 pamphlet, Women and the Subversion of the Community, wfh quickly became a transnational phenomenon. Dalla Costa and James were seasoned activists in Italian and British-American Marxist working-class movements – James in American and British labour, anti-colonial, and antiracist work, and Dalla Costa in the Italian autonomist Marxist tradition that stressed the self-activity of the working class, untethered from established unions.11 Silvia Federici’s writing on the expropriation of women’s unpaid labour, including her positive characterization of lesbianism as a form of anti-capitalist “work refusal,” also shaped the activism of wfh and Wages Due.12 Together, these three women formed the wfh International Feminist Collective in 1972, with groups affiliating in Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada.

Each wfh group, as Montréal activist and historian Louise Toupin notes, had its own “unique alchemy.”13 Depending on the country and city, wfh also had subgroups, including Black Women’s Wages for Housework and Wages Due Lesbians (often called Wages Due), and specific campaigns relating to social services, domestic workers, mothers on welfare, immigrant women, students, and sex workers. Transnational political discussions and the presence of Black Wages for Housework, former members claim, encouraged discussions of race and racism – which is not to say that fissures based on race were never apparent.14 The movement also created a welcoming space for lesbian activism, which set it apart from some feminist groups where homophobia was expressed, and yet was also distinct from lesbian separatist organizing.15

Most wfh groups shared an analysis of women’s domestic labour as invisible and undervalued, even though that labour produced “value” for capitalism. In the Italian autonomist tradition, housework was part of the larger “social factory” of capitalism, a form of unpaid reproductive work encompassing both material and non-material labours, the latter including emotion, sex, and affection.16 Similar kinds of undervalued, invisible labour extended into the work that women did for pay. Domestic labour was also implicated in coercive heteronormativity; the heterosexual household was a form of social discipline that sanctified heterosexual coupling and denigrated lesbianism.

The 1970s provided an auspicious political environment for wfh. Even liberal feminist groups, including the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, were challenging the idea that homemaking was a natural and inevitable choice for women and arguing that domestic labour contributed to the gross national product (gnp) and gross domestic product. In 1977, the government-appointed Ontario Advisory Council on the Status of Women (acsw) commissioned a study of “the housewife,” which emphasized the contribution of domestic labour to the gnp and criticized the denigration and discrimination associated with homemaking.17 Discussion about wages for housework also made it into the mainstream press, not least because wfh made a point of participating in public debate.18

On the left, feminist theoretical projects in the 1960s and 1970s were exploring connections between capitalism and patriarchy, including the political economy of domestic labour.19 Canadian Marxist-feminist Margaret Benston kickstarted this theoretical debate in 1967 with her article “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation,” which both unsettled and inspired left-wing movements trying to reconcile Marxism and feminism. A voluminous international debate about reproductive labour ensued, with Canadian writing playing a significant role.20 Selma James’ “galvanizing” 1973 tour of Canada promoting wfh had an impact, as one Montréal activist remembered: “theoretically, I thought the questions she raised were important; strategically, I did not agree with the Wages for Housework strategy.”21

wfh was part of this international debate, though it developed its own distinct analysis of the gendered and racialized hierarchy of waged and unwaged labour that emerged with global capitalism. While women’s work in the home was ideologically constructed as a “labour of love,” wfh countered that it represented a system of gendered coercion and economic subservience intrinsic to the “capitalist wage bargain.” Demanding money for housework (not housewives, they stressed) was subversive to capitalism and would develop women’s power as they resisted their subordination. This campaign also challenged the foundations of heteronormativity such that “wages for housework” was simultaneously “wages against heterosexuality.”22

wfh also emphasized the importance of grassroots, self-active, autonomous anti-capitalist organizing that was not limited to the employed working class. Nonetheless, the Toronto wfh situated itself within socialist “worker” traditions, symbolized by its choice of May Day for a rally at city hall in 1975. Over 200 attendees listened to wfh speeches, while members distributed leaflets in English as well as “immigrant” languages – Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. wfh speakers challenged the distinction between women’s private and public labour by pointing to women’s shared oppression: “Eight of us spoke from different locations. As nurses. As waitresses. As office and factory workers. As welfare mothers. As lesbians. Each of us linking ourselves to one another” and connecting “wages for housework to the rest of the working class and to the self-activity of women internationally.”23 A wfh May Day event the following year made the point that “serving” labour, taught to women “from childhood,” and “bound up with our identities,” needed both recognition and payment.24

Other than Intercede, a later campaign organizing domestic workers, the waitresses’ mobilization was the Toronto group’s only foray into workplace organizing, and it lasted only two years, which is likely why it is mentioned but not explored in depth by other scholars.25 Yet it was a significant example of wfh’s understanding that they had to address women’s paid as well as unpaid labour and the connections between the two.26 The Toronto group’s other initiatives also touched on women’s low-wage labour, poverty, lack of social power, and the oppression occasioned by the patriarchal, heterosexual family.27 It supported the preservation of Nellie’s, a Toronto hostel for women, and led a campaign, “Hands Off Family Allowance,” to protect the federal family allowance paid to mothers after it was frozen in 1976. A Ryerson Polytechnical Institute initiative, recalls wac member Dorothy Kidd, drew together white and racialized students, including single mothers, who fought for better funding for women’s continuing education. The Toronto wfh group sponsored speakers who addressed “hookers and housewives” as workers and staged a protest against the rising number of “rapes which begin at home” and were never reported as they were committed by a “father, brother, uncle or husband.”28 A key legacy of wfh was the Lesbian Mothers’ Defence Fund, which provided aid to lesbians fighting legal battles for child custody, at a time when courts were largely unsympathetic to their claims.29

Some feminist circles were open to the ideas promoted by wfh. An editorial in The Other Woman, a feminist newspaper sympathetic to lesbian organizing, reminded its readers that housework was literally everything women did to serve men: “housework is getting coffee for your boss, making love, grocery shopping, going to the movies, serving others, changing your baby’s shitty diaper, looking attractive, being a ‘mother’ to a coop house.” Echoing a stance taken by Selma James, the editorial added, “it is not the money [of a household wage] itself which will give women power, but the struggle to get the wage.”30 A swift response by wfh clarified its point of view and offered a different definition of lesbianism, but it was not hostile. Whether women were fighting for welfare for single moms or control of their bodies, the letter noted, they were engaging in anti-capitalist struggles, since “money is power” and capitalism “harnesses our bodies, our time, our very personalities” for profit.31

Other feminists were not sympathetic. Grappling with women’s domestic labour may have been in the political air, but wfh’s call for a wage for housework was rejected by many feminists in Canada and beyond, and some claimed wfh was dogmatically “obstructionist” in its organizing style.32 Feminist antipathy reflected important material and ideological changes in women’s lives at the time. More and more women, especially those with families, were working for wages: feminists thus prioritized equality in the labour force and challenged the popular image of domesticity as the primary, appropriate, and desired role of all mothers.33 Many feminists identified this hegemonic, moralizing opinion as a problem, as did some progressive unions, which understood that this ideological construction of domestic femininity propped up an outdated male breadwinner ideal.34

Wages for housework was perceived as a retrogressive demand, returning or “chaining” women to the home, perpetuating their oppression. Opponents could point to Selma James’ own writing, which asserted that women’s integration into the labour force was not a viable path to emancipation.35 Black and socialist feminists had specific critiques: in the latter case, they emphasized the need to socialize, not “privatize,” work associated with domestic labour.36 Feminist opponents raised a slew of objections: Who would pay? If the state, would women be beholden to state surveillance? Would this discourage collective social services? And so on. When the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (nac) refused membership to wfh in 1979 because their platforms clashed, the ensuing debate was heated.37

This contentious climate is important to the story of the wac as it struggled to widen its political support. A singular focus on wfh’s demand for wages for housework, however, risks overshadowing other elements of its analysis. wfh’s insights about the (hetero)sexualized demands of women’s service work, its critique of women’s low wages within capitalism, and its emphasis on the importance of organizing women, from the ground up, to secure recognition for their “invisible” work all shaped the waitress campaign. Moreover, former participants recall that the wac was not completely siloed. Its members were part of left-wing and feminist “networks” of the time, based on multiple points of intersection: progressive acquaintances, cooperative living arrangements, friends from “free” high schools in Toronto, socialist parties, the New Democratic Party (ndp), and labour movement campaigns.38 The growing number of lesbian community spaces (bookstores, dances, etc.) was also important to Wages Due.39 This plethora of political networks was characteristic of 1970s feminist organizing. “Women’s liberation” was increasingly channelled into multiple, even divergent, campaigns involving political choices and conflicts; nevertheless, personal and political histories remained significant threads connecting feminist organizing.

Aside from these networks, the Toronto wac could count on endorsements from wfh chapters abroad and strong support from the local wfh group: they discussed their organizing with other wfh members, who offered feedback based on their understandings of women’s needs and oppression. When the wac reached out to waitresses, often responding to their inquiries, it often enclosed copies of the Wages for Housework Campaign Bulletin, hoping to popularize the wfh perspective. Both wfh and the wac, it explained, wanted the same thing: “more money in women’s hands.”40 Yet the wac’s organizing notes show it had to overcome the anxiety of potential allies concerning its ties to wfh. One textile union labour organizer urged the action committee to secure more widespread waitress support to give itself more “credibility,” showing it went “beyond” the wfh members who made up the core of the organization; other minutes note that certain newspapers and potential supporters stated firmly that they “did not want to hear about the [wfh] campaign.”41

The Political Economy Context: Business Lobbies for a Differential

The wac originally emerged in response to the tip differential, but this issue was related to economic shifts in the mid to late 1970s. In Ontario, there had been ongoing debate between political parties about the appropriate minimum wage, which was a pressing issue as a result of recession, high inflation, lagging wages, and the contentious federal wage and price controls instituted in 1976 and opposed by trade unions and the ndp. Inflation in the mid-1970s reached a whopping 10 to 11 per cent; however, the federal controls led to wages falling far more than prices, despite strikes of organized workers to keep pace with the cost of living. High unemployment rates of 6 to 8 per cent added to economic uncertainty and the sense of working-class grievance that only workers were paying the price for inflation. Unionized workers could at least argue about raises with the federal Anti-Inflation Board; precarious workers like waitresses were far more vulnerable.42

The Conservative government in Ontario, led by Bill Davis, was also moving toward a “market-oriented austerity” agenda.43 An anti-cutbacks movement emerged in response, formed from an array of social movements objecting to clawbacks in social services, welfare, and education. Many wfh campaigns in the 1970s, remembers Judith Ramirez, “invariably” arose from governments’ increasing attacks on women’s economic security and prospects.44 wfh activists responded with defensive campaigns that simultaneously exposed the underlying, systemic oppression they believed framed women’s poverty and lack of power.

In March 1976, a slight increase in the Ontario minimum wage to $2.65 was accompanied by a freeze on the minimum wage for those serving alcohol at $2.50. This fifteen-cent differential, in essence a rollback, was a concession to lobbyists like the Canadian Restaurant Association, which insisted publicly it could “not afford [any] minimum wage rate” hike or restaurants would “price themselves out of the business.”45 This cabinet decision had been made in late 1975, following entreaties from Tourism Ontario, an umbrella lobby for restaurants, hotels, and resorts. That group’s internal bulletin crowed that the government’s adoption of “their” policy was proof they were being “heard” by the government.46

Servers in restaurants and bars were alarmed when Claude Bennett, Minister of Industry and Tourism, publicly announced at an Ontario Motel Association meeting in November 1976 that the government was considering further lowering the minimum wage for servers, widening the differential, and even extending it to other hospitality service workers. The wac was formed in response and immediately pressed the government for clarification. The action committee’s concern that a lower minimum for waitresses would become policy by stealth was warranted: not only was the government seen to be a mouthpiece for business, but minimum wages were administrative, regulatory decisions. No legislation was needed.

Bennett’s announcement, said the wac, was a sop to the tourism industry’s “crying about the loss of profits.”47 This was quite right. Tourism Ontario’s brief to the government insisted the industry was in crisis, due in part to competition from the United States. Unless the minimum was frozen, businesses would suffer, even fold, leaving people unemployed. Serving work, the lobby group argued, was “low profitability” labour that left small margins between costs and profits; other hospitality workers, such as valets and chambermaids, also in this category, should be included in the tip differential. For these employers, the “very concept of the minimum wage” was “open to question,” as were various rights such as paid statutory holidays and benefits, which they also wanted abrogated.48 Claiming competition blues, they pointed to legal jurisdictions, such as Québec, which already had a tip differential for waiters and waitresses.

Internal disagreement between Ontario government ministries soon became clear. The Minister of Labour, Bette Stephenson, presented research to cabinet from her policy experts recommending slightly larger increases in the minimum wage without a widened differential, but ministers from Tourism and Industry, Food and Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Treasury Board parroted the business lobby’s call for a brake on wage increases. Two ministers tried to dissuade Stephenson by claiming a higher minimum would create an “inflationary” effect on wages (disproved by the Ministry of Labour’s research) and would make it difficult to find cheap, temporary harvest labour. In the vanguard of neoliberal ideology, treasurer Darcy McKeough opposed all minimum-wage increases, urging Stephenson in late 1977 to “stand firm,” despite government statistics showing that lower-wage workers were falling badly behind.49 Frank Miller, Minister of Natural Resources, had no shame in sending a lobby letter to Stephenson on his ministry’s letterhead, complaining that he had told her multiple times about the profitability “problems” and “unfairness of some of the rules” in tourism based on “his lodges” that he ran in northern Ontario.50 Papering over internal government differences, Stephenson resorted to an evasive, bureaucratic-speak announcement that “inter-ministerial discussions” were underway.51

While ndp members of the legislature castigated the Minister of Labour for constantly studying the minimum wage but never delivering a better one, there was an element of truth to these “studying” claims. Labour Ministry policy researchers were embroiled in internal discussions, including which economists should assess the minimum wage, how to measure its impact, and whether to have a public inquiry. Still, their policy recommendations outlined rationales for raising the minimum wage gradually, taking inflation into account, and using the average hourly wage in manufacturing as a benchmark: the minimum should not fall below 42 per cent of this average. They were hardly radicals. The minimum wage, they reasoned, was not meant just to prevent exploitation but also to keep business competition fair, to allow workers to live at “subsistence” levels, and to keep wages above welfare rates so low-wage earners would stay in the workforce. They pointed out that minimum wages usually “followed” but never led price increases and that the current “deteriorating” rates were diminishing workers’ purchasing power, leaving more families below the poverty line.

Ministry of Labour civil servants tried to use hard data to make their case for more substantial minimum-wage raises. First, they mentioned that the fifteen-cent differential was devised quite “arbitrarily” since there was no existing research on tip amounts to measure its impact.52 Second, an increased minimum would provide tangible benefits to business: less staff turnover, an incentive for workers to avoid welfare, more money circulating in the economy, and so on. While they conceded that increases would impact the tourism industry more than others, their research contradicted Tourism Ontario’s claims that wages were destroying profitability. A higher minimum wage would only add about 2 per cent to the total operating costs for these businesses, and other costs, such as rising gas prices, were actually at the heart of their economic problems.53 Their argument did not convince the cabinet. When the government finally raised the minimum wage, it was still lower than the Ministry of Labour’s very modest suggestions, and cabinet also ignored the ministry’s recommendation on the differential. Clearly, Miller and McKeough were more persuasive, representing Ontario’s neoliberal future.54

Waitresses Mobilize

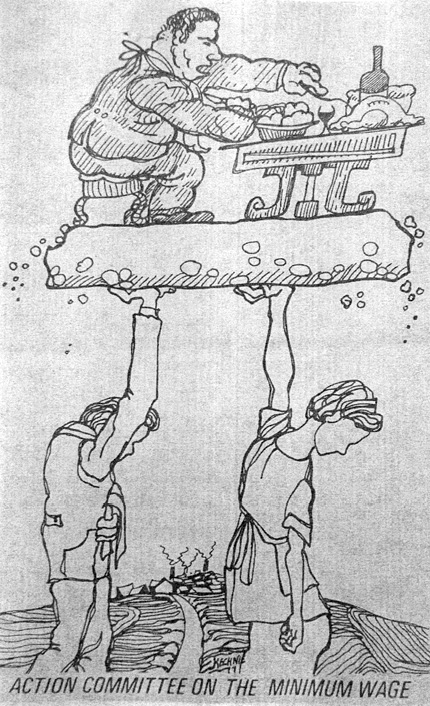

Claude Bennett’s public claim, echoing business, that service workers should accept “lower” wages because “huge sums” of money were accrued in tips was the spark that created the wac.55 Waitresses were incensed; this false picture of their income simply spurred on their organizing. A core group of about eleven wfh activists and supporters, many with waitressing experience, established the wac to counter business and government plans, though their aim was also much broader: to nurture feminist resistance to women’s oppression originating in the link between their unpaid domestic labour and undervalued paid labour.

The wac argued that many women were “lunch counter” servers with lower tips and wages.

Courtesy of Toronto Public Library, Toronto Star Photograph Archive, photographer Doug Griffin.

Recent changes in the gender makeup of the waitress workforce made this issue especially prescient. Past prohibitions on hiring women to serve alcohol had been recently swept away; by the 1970s, not only were more women being hired in bars, but more restaurants had liquor licences. Despite these changes, most waitresses still worked in smaller, less expensive family- or proprietor-owned bars and restaurants. While men laboured in “high-end venues,” women were “lunch counter” servers.56 Unionization was very limited, so few women enjoyed even the most basic protections of a collective agreement. Many women had no choice but to accept irregular hours or part-time work, and they were required to “tip out” to others before taking their share; these “kickbacks,” as the wac called them, were identified as another subsidy to employers who did not pay everyone a decent wage.

Moreover, as the wac constantly emphasized, women had to “hustle” to make tips, using their sexuality or perhaps adopting a maternal pose, selling themselves in ways male waiters did not.57 Women were pressed to “show cleavage … smile a lot and use sexual innuendo … act coy and alluring” and to accept physical advances and verbal abuse from men without complaining.58 The tip differential would intensify pressure to perform this extra emotional and sexual labour for bigger tips, in order to compensate for the lower minimum wage.

There were other opponents to the differential, including some unions and the ndp, but the wac took the initiative, creating a spirited, public protest. One factor behind the committee’s success in making the differential into a political issue was the feminist commitment of the small group of wfh and Wages Due activists involved in the wac, particularly Ellen Agger, who did much of the correspondence and public speaking. Agger’s organizing ingenuity and articulate promotion of the waitresses’ cause was invaluable, though others were involved in brief writing and speaking. Twenty-four at the time, Agger worked as a waitress in 1973 and 1975 in jobs characterized by arduous labour and sexism. It was “brutal” on one’s feet, she remembers, and working the lunch hour entailed intense time pressure to deliver meals, yet small tips for lower-priced orders. At all five workplaces, she “got into trouble” for objecting to bad conditions. At one, she took the owner to small claims court (and won) for their illegal paycheque deductions for food; in many others, she experienced routine sexual harassment from both customers and other staff that women were expected to tolerate. One cook carved penises out of carrots to place in the waitresses’ gathering space; male customers in another restaurant/bar ran their fingers down the buttons on her required, revealing “costume” and made lewd comments about her breasts. In the higher-end Royal York hotel, where the part-time waitresses were assigned to the lower-price Gazebo Room and the waiters to the higher-end Imperial Room, she quit rather than wear the required high heels.59

In 1976, Agger worked as a youth employment counsellor on a short-term, government-funded Opportunities for Youth project. In this job, she still had time to do wac organizational work and could also access a mimeograph machine, a basic technological tool for organizing at the time.60 Her waitressing experience gave her the ability to speak meaningfully about work conditions, while her current position protected her from being fired from a waitressing job – a common employer response to servers who complained. A graduate of a Toronto free school, she already had grassroots political experience through Wages Due and the family allowance campaign; Aggers and fellow wac member Dorothy Kidd had gone door to door in Regent Park with the wfh petition. At a 1976 rally protesting budget cuts, Agger spoke about how social service cuts differentially hurt lesbians. In a telling comment on trade unions, she suggested that, after women had done “unpaid” work for unions for years, it was now time for unions to support lesbian rights.61

The strategies developed by the wac were shaped by their astute analysis of the structural limitations on reaching a scattered and transient workforce that included many women who worked part time.62 A substantial group of “older” women, in their 30s and 40s, also had family responsibilities.63 The labour law regime, based on union locals representing a workplace or a group within a workplace, was not conducive to organizing; however, the wac eschewed worksite organization for an occupational mobilization outside of the existing union structures. One problem, the wac conceded in a letter to a Kingston waitress, was that waitressing was often a “filler” job for women between other jobs or in hard times, so “once a waitress, you are not always a waitress.” Even if women continued to do the job, they might move from one locale to another. Recognizing “how dangerous and difficult” it was to organize at the workplace, as well as women’s reluctance or inability to attend meetings that clashed with child care, the wac developed alternative tactics: petitions, publicity, lobbying, and alliances with politicians, feminists, and a very wide array of social movements.64 “We never intended to make a big membership drive,” Agger wrote to a waitress in Waterloo near the end of the campaign; the wac’s tactics reflected “who we are in ways that would reflect our own lack of time.”65

The small wfh and wac instigating group tried to locate grassroots waitress supporters and raise public awareness, as well as secure endorsements from organizations to emphasize the breadth and interconnections of this workplace issue. They did not focus only on obvious allies; they approached Lynne Gordon, head of the acsw, and Laura Sabia, a Tory, as well as more progressive groups. By 1977, the wac’s list of supporters protesting the differential included legal reform groups and immigrant, feminist, lesbian, antipoverty, educational, social service, and labour organizations; they accrued 33 official endorsements. Given the wac’s small numbers, this outreach was nothing short of astounding.66

Most responses to the wac indicated a shared concern about the ongoing economic fallout of cuts, inflation, and declining wages in women’s lives. The combined class and feminist message of the wac appealed; a local antipoverty group offered its immediate support, promising to write to the government and noting that the issue spoke to “sole support moms,” likely because some women with dependents moved in and out of waitressing to try to make ends meet.67 The class message was less appealing to some groups, including the politically cautious Ontario acsw; it took a long time to create a lukewarm resolution of support. If an organization refused to endorse, as did chat (Community Homophile Association of Toronto), Agger followed up with further persuasion. If she encountered politicians gladhanding in public spaces, as she did with both ndp leader Stephen Lewis and Conservative Larry Grossman at the Bathurst Street United Church festival in the summer of 1977, she queried them on their views on the differential and waitresses’ wages.

The wac worked the phones to raise public awareness, but it also circulated its brief, originally written for the provincial Department of Labour and Department of Industry and Tourism early in 1977. Any inquiry the committee got, out went the brief and the petition, titled “Money for Waitresses Is Money for All Women.” The brief was a tightly organized, well-argued, and convincing document that earned the wac respect. A seven-page analysis, it covered a history of the tip differential, including the strong business lobby behind it, and the biased nature of that lobby’s selective comparative statistics drawn from other regions and the United States. It also exposed a secretive provincial government unwilling to publicly acknowledge what it was planning vis-à-vis the minimum wage.

The brief held that the tipping system should not be considered a wage but rather a payment for service that might or might not be paid, and it noted that tips subsidized employers, not workers, since they allowed owners to pay low wages – something Ministry of Labour researchers privately said too. Those hurt most by a growing differential, it showed, were those at the bottom of the workplace hierarchy in hospitality – women, sole support mothers, immigrants. Most waitresses made close to (if not only) the minimum wage; a statistical appendix showed the wage gap between male and female workers in general and food servers in particular. Women and men were rewarded differently for their work, in part because of the gendered hierarchy of service labour, with men working in more prestigious locales, but wage differences were still striking. Although women made up the majority of the workforce, they earned at least a third less than men in the same job.68 Waitresses who had to support dependents, the wac brief showed, were poised close to or below the poverty line.

Agger quoted waitresses interviewed in the press who pointed out that their wages were supporting families and that, even with tips, the money they earned “barely kept the wolves from the door.”69 The brief asked why waitressing was deemed a (low) minimum-wage job, and here, the views of wfh were clear: serving was considered women’s work that required no training, as it was an extension of their work in the home. Many women, moreover, took up waitressing as their only alternative to “wagelessness in the home.” Just as women in the home provide “cheap labour,” so did women and immigrants in serving jobs, with the latter always “with the gun of poverty to their heads.”70

wac material sometimes grouped women alongside other oppressed groups in the workforce, such as “immigrants, Native peoples, Blacks.”71 A more extensive analysis of race and serving employment was not part of this campaign. Indeed, the wac usually used the category of “immigrant” rather than identifying “race” to denote those in the hospitality industry who were lower paid and vulnerable – a reflection of contemporary immigration and work patterns. At the time, Indigenous, Black, and people of Asian descent were a small, though growing, part of Toronto’s working population. The vast majority of the working class were Canadian-born and European/British immigrants who claimed British, French, and European “ethnicity,” particularly in terms of language and culture.72

Restaurant work was a reflection of pre– and post–World War II working-class immigration from Britain and Europe; indeed, this is one reason the wac sought out endorsements from immigrant organizations such as Women Working with Immigrant Women. According to the census, food and beverage servers were predominantly white, with the majority born in Canada. Still, immigrants from Europe made up an important part of the workforce, and it was these workers who were perceived to be more vulnerable; undoubtedly, some were “racialized” southern and eastern European immigrants. Discrimination likely also played a role in keeping the workforce white, due to employers’ preference for white applicants. One waitress in contact with the wac told them that in 1969, there were two Black women in Toronto serving alcohol, and she was one of them.73

The brief’s extensive list of the unacknowledged, unpaid “domestic” labour of waitresses showed the influence of wfh, though it echoed other feminists’ emerging critiques of the sexualized and gendered job performance required of women, particularly in feminized white-collar and service jobs.74 If earning tips helped to “keep the wolves from the door,” it also pressed women into certain emotional and sexual roles that were required to get any tip. Getting and keeping the job meant spending time and money on your appearance, body work that was then displayed in humiliating ways for management’s approval. In a Branching Out article, Agger described having to “parade” her body in interviews and, once on the job, the pressure to exhibit flirty “sexual behaviour,” always “acting heterosexual.”75 Constantly suppressing one’s anger at being belittled, infantilized as a “girl,” and harassed entailed extra emotional labour too.76

Waitresses were also forced to do extra jobs such as cleaning washrooms, to labour before and after their paid shift doing set-up and cleanup, and to sacrifice break time because of understaffing – what today we would call wage theft. They were required to pay for “walkouts” who skipped out on their bills, and they were substituted for other jobs such as cashiers. Because they were held accountable for illegal alcohol service to underage customers, they could easily lose their jobs. As Agger recalls, this also meant they were supposed to “cut off drunks,” a daunting if not dangerous task for women dealing with angry men.77 Tipping out might mean contributing a portion of their tips to better-paid maître d’hotels, yet waitresses found it difficult to protest a practice that was not part of the official wage system.

The wac finished its brief with a list of demands, including a higher, common minimum wage for all workers and stiff labour regulations to force employers to pay for all their labour time. They demanded that employers not hold them responsible for walkouts or illegal liquor service and end tipping out, or “kickbacks,” by paying all workers within the restaurant sector decent wages. The appendix included powerful testimonials from waitresses who described being “grabbed and touched” by customers, fired for the smallest effort to assert their rights, or pressed by bosses to “give them a kiss.”78

The brief was informational, educational, and agitational. Its circulation gave the differential issue considerable visibility, which was essential if the wac was to stop wage changes made behind cabinet doors. Only publicity would bring the debate to the public. Contrary to a view of the wfh as singularly dogmatic, these wac tactics were inclusive and expansive. As Dorothy Kidd, also active in Toronto wfh and Wages Due, remarked in retrospect, “if we were partisan in our rhetoric, we were not in our organizing.”79

Waitress inquiries and political endorsements came primarily from Toronto, though support grew across the province, in part due to the wac’s smart use of the media.80 The wfh women taught each social movement skills like typesetting, printing pamphlets, and making videos, as well as how to use press releases to garner tv, radio, and newspaper coverage. The wac also responded promptly to news stories of any relevance with letters to the editor. When the Toronto Star covered an economic study that claimed “full employment” rather than higher minimum wages would restore the economy, Agger countered by arguing full employment at low wages would only lead to “spreading the poverty around.”81 Kidd remembers some left-wing and feminist critiques of their strategy of engagement with the mainstream, corporate media, since it was far from feminist friendly. The wac, however, felt the media had to be cultivated and used to attract the attention of many women who were unattached to the feminist movement.82

The use of radio was especially productive as the wac secured scores of interviews in Toronto and other Ontario cities; the wac campaign fit with current political preoccupations, including feminism, women’s work, and the minimum wage. Local tv was useful too. In July of 1977, Agger braved an appearance on City tv’s Free for All, a debate-format program in which the audience was encouraged to take sides. She received a positive letter afterward from a woman viewer who thanked Agger on behalf of herself and her friends for speaking out “on behalf of older women”83 The wac’s media savvy was critical to its ability to convey a message beyond its own small numbers and the limited reach of the women’s movement.

Pamphlet supporting the wac created by London Action Committee on the Minimum Wage.

“Minimum Wage Tip Differential” file, box 214294, Ministry of Labour 7-1, Archives of Ontario.

The wac’s success in garnering public support was evident in the letters of protest sent to the Minister of Labour and the Minister of Industry and Tourism. Thoughtful and sometimes extensive, these letters described women’s structural disadvantages in the workforce as well as the inherent unfairness of the differential. A mere $2.65 an hour was “scarcely enough to live on,” wrote the Christian Resource Centre, while the ywca pointed out that women in general made 55 per cent of a male wage, and there already was a “differential” in the restaurant industry as women were relegated to lower-wage venues. The Law Union of Ontario laid out a long list of objections, including the fact that a tip differential would further disadvantage workers who were seldom unionized and thus some of the most economically vulnerable – those who “can least afford it.” Moreover, the differential would set a dangerous precedent for other business lobbies.84 Some letters to the Minister of Labour came from natural allies: two ndp riding associations, Times Change Women’s Employment Service, and the Northern Women’s Centre and Women’s Resource Centre in Thunder Bay and Timmins, respectively. Others indicated the wac’s persuasive ability to reach out to less obvious supporters, such as the Business and Professional Women’s Club of Fort Frances, which endorsed the brief. So too did the Thunder Bay city council.85

Waitresses also responded individually with calls and letters to the wac. These were not simply the result of the wac’s smart communication skills. Waitresses were angry. What the wac outlined – uncertain employment, wage theft, sexualization, “hustling” for a tip – applied everywhere, and women had had enough. They wanted copies of the brief, the petition, information on what they could do, or simply to vent their unhappiness with wages and working conditions. A few wrote directly to Labour Minister Bette Stephenson. The “work is no joy,” wrote one Thunder Bay waitress at a licenced steakhouse; it entailed constant stress from uncertain pay, fear of losing the job, and “boorish [customer] behaviour” that “drove her to tears…. Something happens to people when they are hungry,” she concluded. “They become less than human.”86 A former waitress who had worked in other countries, even as a maître d’, identified exploitation as transnational: “It has always been a slave trade, with the poorest working conditions, paying the lowest wages.”87

As the government dug in its heels on the differential in 1978, a Kitchener waitress blasted Stephenson. The government policy was “sexist” since it discriminated against most women at “less classy establishments,” and it ignored all waitresses’ unpaid labour. In her job, she filled in for other workers; as a result, only 50 per cent of the time was she even able to get tips. The government also ignored the health hazards of the job, including noisy, smoky bars where waitresses “risked being injured in fights between customers.” Some waitresses, she wrote, spent their paltry “nickels and dimes” tips on taxis to get home late at night. She identified the true culprit – the tourist industry, demanding small savings “on the backs of the hired help” – and suggested that the business lobby’s comparisons with American wages was “unfair to Canadian workers.”

She ended with a comparison the wac also made in its publicity: “I find it ironic,” she wrote, that “well paid” government officials, who voted on their own pay increases, were depriving waitresses of “25 to 50 cents” an hour.88 Finger pointing about the class interests of the government were apparent in other protest letters. “We need an equitable incomes policy, not one that decreases the earnings of working people in lower economic brackets,” wrote a woman from West Hill. “I wonder when the government will treat working people as well as they do [those] in the upper middle class.”89 Others implied that the Tories, eating at “high class” establishments, naturally did not understand the issue, while one letter offered a sarcastic take on Premier Davis’ recent election slogan: “Davis for all the people – well, just not waitresses.”90

Enlarging Community Support

The stories waitresses told the wac contradicted any notion that they were perfectly happy because they made enormous tips. Low wages and lack of respect were high on their list of complaints, but they also noted difficult working conditions and the lack of dignity accorded a job that required mental and physical skills such as “juggling, diplomacy, and a good memory.”91 The wac tried to answer all letters and offered to speak as far away as Ottawa and Thunder Bay. Two wac members travelled to Milton to meet with cocktail waitresses at the Mohawk Raceway. The women “shared their experiences” with the wac, including their fears about any and all organizing on the job as hostile bosses hovered, though one waitress declared she was so “angry” that she was willing to “risk her job.”92 The wac offered the best advice it could to these women. Given the difficulties of organizing at the worksite, committee members could hold meetings in their homes, use the media to reach out to other waitresses, advertise through community papers and venues, or leave wac materials at places frequented by women, such as shopping centres, laundromats, and ywcas, as the wac had done in Toronto.

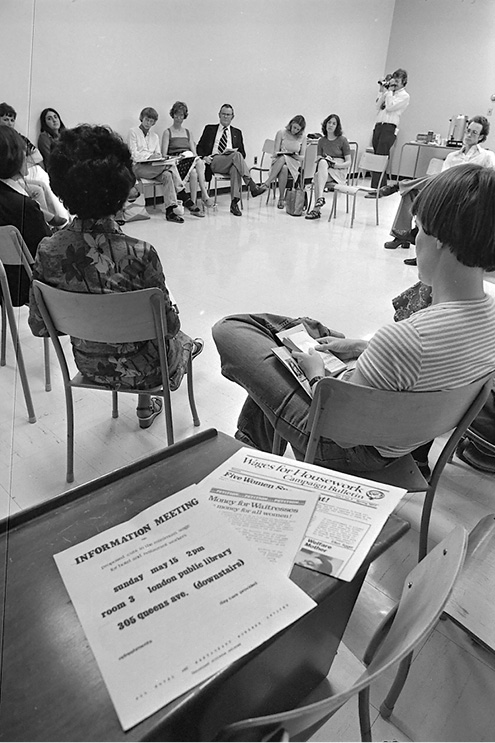

wac information meeting at London Public Library.

Courtesy of University of Western Ontario Archives, London Free Press Collection. Photographer: Graham.

Prompted by the wac campaign, the London Working Women’s Alliance took up the minimum-wage issue. Ellen Agger, Elizabeth Escobar, and Dorothy Kidd spoke about the waitress mobilization at their small organizing meeting in May of 1977. Escobar opened with a personal testimonial: after 25 years of waitressing, and as a widow with six children, she knew the minimum, even with tips, was inadequate. Many attendees indicated their fear of being discovered and fired if they even signed the petition; one downtown employer had told his waitresses “not to go” to the meeting. A representative from the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union agreed that fear was a factor in low unionization and suggested “informational pickets” instead, a tactic that had worked in the United States.93 In early June, the Working Women’s Alliance followed up with a protest march through London’s downtown, leafletting about the tip differential and engaging with onlookers. Although “enthusiastic,” the protest was quite small, reflecting the difficulty of mobilizing waitresses and waiters through “traditional” union drives and street protests.94

Minimum-wage protest in downtown London, 4 June 1977.

Courtesy of University of Western Ontario, London Free Press Archive, Photographer: James.

Inquiries also came from waitresses and women’s organizations in North Bay, Timmins, Kingston, Ottawa, and Thunder Bay, as well as smaller towns including Havelock and Brantford. Groups from other provinces also wrote, often having read about the wac in one of the many feminist newspapers that thrived at the time. Agger wrote an excellent article for Alberta’s Branching Out, while Vancouver’s Kinesis also did a piece on waitressing and the wac. Ontario coverage in the Wages for Housework Campaign Bulletin, The Other Woman, and the Northern Woman Journal also encouraged a letter-writing campaign, either to local newspapers or to cabinet ministers, calling for a public forum on the minimum wage.95

The feminist press provided a particularly sympathetic ear, though not all mainstream journalists were unsympathetic. Toronto papers, especially the Toronto Star, interviewed waitresses who provided experiential confirmation of the precariousness, low pay, and lack of employment protections in the job. Coverage sympathetic to the waitresses irritated the tourism lobby, which responded with letters to the editor.96 A related public debate about tipping out continued in 1979 and 1980, even after the wac was inactive, as more wait staff protested the practice. Some unionized restaurant workers filed grievances, though arbitrators were not consistent in their rulings.97

Sadly, though, some male journalists were more interested in covering the contemporaneous debate about topless waitresses. As bar owners turned to topless or scantily clad waitresses to enhance profits, they met some resistance. Waitresses who were replaced because they would not partially or fully expose their breasts protested, even picketed, and one politically savvy waitress filed a human rights complaint after she was told to “take her blouse off” in an interview as the job was “topless.”98

The sexual harassment that waitresses described was increasingly becoming visible in feminist writing, but legal and human rights protections were rudimentary at best.99 Unionized waitresses who grieved being forced to wear revealing “harem costumes” lost their case. Unionized waiters who complained when they were replaced by topless women garnered more sympathy.100 The city and the province became embroiled in morality debates about regulating topless waitresses and adult entertainment. Male journalists guffawed over their supposedly witty headlines like “bare service only” and “busty dining,” making light of employers who insisted they did not hire older women because “no one wanted to look at them with their clothes off.”101 (As the wac argued, hiring for all waitress jobs was often biased against “older” women.)

Reporters also tried to create a wedge between topless waitresses and the wac, portraying the latter with the stereotypical trope of the moralistic, judgmental feminist. The opposite was true: Agger protested the journalist’s effort to create a “false division” between wac women who wanted “dignity” and topless waitresses who supposedly “like to be exploited.” The wac did not judge any women trying to make a living, since all waitresses want the same thing: “money, good conditions and respect.”102 Even the Ontario Federation of Labour (ofl) convention “snickered” over the topless waitress issue when it was raised as a problem by the Bartenders union – until a female flight attendant intervened and told the delegates to stop laughing about women’s “exploitation.”103

The wac knew it needed more than columns in the feminist press and official endorsements; it required allies who had the ear of the mainstream media, could join it in lobbying politicians in the legislature, and would get the wac a hearing with the Ministry of Labour, which it correctly suspected was more sympathetic than Industry and Tourism. Feminist groups concerned with workplace issues proved the most proactive, as were some ndp members of the legislature. Unions, as discussed below, were not.

The Ontario Committee on the Status of Women, an alliance of liberal, labour, and social democratic feminists, swung into action very quickly, offering advice on tactics and sending letters to the government and the media.104 Representing them, feminist economist Marjorie Cohen wrote repeatedly to both Claude Bennett and Bette Stephenson, as well as to newspapers.105 In a long newspaper opinion piece, Cohen laid out the policy contradictions that waitresses faced. The province claimed tips made up part of the “wage,” and the federal government agreed that tips should be counted as income for tax purposes, but tips were not counted when it came to unemployment insurance rates (or Canada Pension, as one “older” woman pointed out to the wac). Whatever the calculation, Cohen concluded, it “will always be to the benefit of government and industry and to the detriment of the worker.”106 It was no accident, she suggested, that the government was targeting low-wage women whom they presumed would not resist. Her intervention, like that of other supporters, pointed to a sad history of the minimum wage: over the decades, businesses consistently claimed that they could not pay, that people would lose jobs, and that workers did not need it. Yet when the minimum was raised, the economic sky never fell.

Organized Working Women (oww) – an autonomous feminist organization of Ontario trade union women founded in 1976 to promote women’s equality in their unions, workplaces, and society – also kept in touch with the wac, defending it when a former head of the Hotel and Club Employees Union and ofl secretary treasurer Terry Meagher “tried to get them out” of an ofl convention on human rights in September of 1978.107 The male leaders informed Agger that the wac was not welcome as it was not a bona fide union. Although oww represented only union women, it supported a range of struggles and had already disregarded Cold War union leaders by welcoming “left-wing” unions like the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union. oww president Evelyn Armstrong reassured the wac that its members could share oww’s convention table for wac information at the larger ofl convention in November.

Even within the government, it was likely a few feminists – including Marnie Clarke, head of the Women’s Bureau, and Constance Backhouse, a law graduate and executive assistant to the Deputy Minister of Labour, Tim Armstrong – who convinced the Department of Labour to finally meet with the wac in the summer of 1978. Stephenson, to the wac’s disappointment, did not come to the June meeting with the deputy minister, Backhouse, Clarke, and staff from Employment Standards. Stephenson did attend a private meeting three months earlier with eight lobbyists from Tourism Ontario, who were confident that their views would reach cabinet.108 Even if her ministry was better informed on the need for an improved minimum wage, Stephenson was well aware of the power dynamics shaping government decisions.109

The wac came to the June meeting with representatives from the Immigrant Women’s Centre and Opportunities for Advancement, a “mothers on welfare” group; this trio reflected wfh’s stress on the interdependence of women’s struggles with low wages, poverty, and discrimination. The wac pushed for a “public forum” on the minimum wage and believed it had a commitment from the ministry, an impression reinforced by oww member Deidre Gallagher. It never happened. A proposal for an inquiry on the minimum wage had been drafted, but not all ministry officials were convinced it would be useful, and in any case, these officials imagined an extended inquiry on policy that would hear from all experts and interests, including business.110 The wac’s “public forum” was to be a focused public event that gave workers a chance to voice their views, including their frustration with stagnating wages. Waitress testimony marshalled by the wac would have been a powerful means of swaying public opinion. McKeough understood this danger and lobbied against an inquiry, warning that such a forum might “involve public pressures we can’t withstand,” especially when the government should be aiming for “the confidence of the private sector.”111

Agger followed up after the June meeting, as she always did, with multiple letters and calls asking for a ministry response. Stephenson’s absence from the meeting was significant. Although the wac continued to fight, it was clear the government was politely meeting with the committee but not listening, and that it did not intend to rescind the differential.

Political Manoeuvrings

Opposition politicians also became embroiled in the tip differential issue, in part because the minimum wage was already a source of contention – and especially so in inflationary times. Through 1975 and 1976, the Ontario ndp opposition asked the Tory government in the legislature when it was going to raise a minimum wage that was lagging behind inflation and lower than that in other provinces. Government ministers were evasive, not least because they could be; legislation was not needed to make changes. As the opposition hounded ministers, demanding answers, the government prevaricated, though Stephenson and the Tories did tell opposition critics that Ontario’s “unique” industrial and wage environment had to be considered, as did the need to be “competitive.” The latter necessitated making comparisons with low-wage American states, instead of higher-wage Canadian provinces.112 Again, the Ministry of Labour’s internal research contradicted these arguments.

Even before Bennett’s November speech, the ndp zeroed in on the tip differential in their criticisms of the government. After it, they decried the government’s “reduction” in the minimum wage.113 In response, the Tories resorted to semantics, claiming it was not a reduction but simply a freeze. Through 1977, the ndp maintained its critical stance on the tip differential and recommended a much higher minimum of $4.00 an hour for everyone. This four-dollar minimum became a key issue in the 7 June provincial election. The Tories, with aid from the media, caricatured this demand as unrealistic and “foolish,” if not ludicrous. Stephenson predicted social catastrophe: employers would have to find an additional $7 billion for wages, and businesses would shutter their doors.114

The election, however, provided the wac with an opportunity to keep its issue in the public spotlight. It developed a template letter asking all candidates for their position on the minimum wage and tips. Many Conservatives apparently avoided the issue. Liberals opposed a tip differential but were extremely critical of the ndp’s four-dollar minimum. ndp candidates were usually supportive, especially those with any experience in or with the hospitality sector. One candidate, whose mother worked “for thirty years as a waitress,” was unequivocal: “I know how hard the work is and for so little [pay.]” Although the ndp became the wac’s strongest political ally, the wac disagreed with some of its candidates’ views on tips. Ian Deans, member of provincial parliament (mpp) from Hamilton, asserted that workers’ dignity would be enhanced if tips were replaced by a service charge for all servers, as in Europe. He seemed shocked at Agger’s temerity in bluntly rejecting this solution. She told him (and others) there was evidence that workers could be deprived of their share of the service charge, so women’s best bet for a living wage right now was an increase in the minimum wage and their ability to keep all tips.115 A few ndp candidates were condescending, informing the wac that it should redirect its efforts to campaigning and voting for the ndp. Petitions “don’t do much good,” one said, adding that the waitresses “should work for them [the ndp] as that is how we will get what we want.”116 This was a constant refrain of social democrats to grassroots labour actions: just rely on us and the parliamentary system.

The wac asked all its allies to raise the issue whenever they could in the election campaign, and it offered to go to all-candidates meetings to pose questions about it. The election kept the tip differential in public view, but the results were inauspicious for the wac’s strongest ally in the legislature. The ndp lost five seats as well as its status as the official opposition, and the media laid the fault at the feet of the supposedly unrealistic $4.00 minimum wage. In the subsequent ndp leadership race, the victor, Michael Cassidy, had been the most wishy-washy on the minimum-wage issue, allowing that there could be exceptions to it. The wac had already taken him to task for his “disappointing” failure to defend “the working people of this province.”117

A few politicians did continue to support the wac’s critique of the differential after the election. The ndp, especially mpp Bob Mackenzie, tackled Ontario’s low minimum wage repeatedly in the legislature; a “shouting match” between him and Minister Stephenson during question period late in June indicated that the policy differences between Stephenson’s and Bennett’s ministries were something of an open secret.118 Using the Ministry of Labour documents justifying a far more substantial minimum-wage increase, Mackenzie asked why the “richest” province was saddling its workers with “almost the lowest” minimum wage.119 ndp criticisms and Conservative prevarications continued into 1978, even after the government had announced its increase in the general minimum wage from $2.65 to $2.85 in February – leaving alcohol servers at $2.50 an hour, now with an even wider differential than the original fifteen cents. ndper Marion Bryden, who had earlier tried to rally mpps to support the wac, used another approach, asking if the tip differential was “discriminatory” toward women, as the wac had shown, and therefore a violation of the Human Rights Code.120 This too did not work.

Despite the best efforts of politicians like Bryden and Mackenzie, the differential had become permanent. The wac publicly claimed a partial victory in February of 1978 for two reasons: the differential was not widened to a full 50 cents as originally suggested, and it was not extended to other hospitality workers, which had been the goal of Tourism Ontario. The wac followed up with an exasperated letter to Stephenson, accusing the government of “sexism” since any differential hurt low-wage women workers and pushed women further into sexualized behaviour akin to “legitimizing prostitution.”121 The ndp also persisted with questions in the legislature about tipping out, showing that waitresses were giving up a large proportion of the tips to subsidize other low-paid workers. This generated enough controversy in the newspapers that the government announced it might regulate tipping out. It did not. In subsequent changes to the minimum wage, a differential remained and later grew to the 50 cents Bennett originally proposed.

“Very Unfriendly” Unions

The wac knew it was politically necessary to engage with unions, yet they were arguably the least helpful groups in the campaign. Early in the fight, the wac sent its brief to the ofl and Metro Labour Council and talked to unions representing waiters and waitresses. At the time, there were two of relevance: the Hotel and Club Employees Union, affiliated with here (the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union, headquartered in the United States), and the International Beverage Dispensers and Bartenders Union (Bartenders), also an international union. The Canadian here union, which focused on staff at large hotels, had weathered a massive and unsuccessful strike at the Royal York in 1961–62, while the Bartenders locals tended to be smaller, located in taverns and hotel bars.122 Later mergers of the two produced the composite Canadian here.123

In 1977, there was a third, momentary player, the Independent Association of Ontario Waiters/Waitresses (aoww), led by Reinaldo Santos, who had been fired for organizing at Ed’s Warehouse restaurant. This association was a self-described “professional” union in favour of a service charge, not tips, as well as industry-wide better wages and benefits.124 Elizabeth Escobar, involved in the aoww but in touch with the wac, explained it too was preparing a government brief (aided by a law firm), and though Agger tried to keep channels of communication open between the two groups, Escobar relayed the aoww’s preference for its own less politicized brand of organizing.125

wac member Boo Watson also tried to talk to Santos directly but was rebuffed. When the aoww held a meeting at Central Tech School (with a subsequent protest march to Ed’s Warehouse), the wac was initially told its members could not even come. Behind-the-scenes lobbying by the wife of a union lawyer resulted in their attendance – on the condition that they remain silent. The wac women claimed there were only fifteen women of about 250 in attendance, and one of the few women, a Black waitress who worked at the Hyatt, confessed to Agger that she wanted her tips, not a service charge. The wac members observed there was “no recognition of women and sexualized labour” in this largely male-dominated group. “Much talk, no action,” they concluded about this effort.126

The two existing unions were unsympathetic or hostile. Their antipathy to the wac was not related to the wac’s stance on the tip differential, which the Bartenders union also opposed, noting in a brief to the provincial government that a lower minimum wage for any servers was a basic bread-and-butter issue that limited its members’ pay.127 It also agreed with the wac that tax collectors going after unreported tips as income was hardly fair – or an accurate portrayal of their income. The Bartenders complained that reports about the feds pursuing people making vast sums in tips unfairly skewed perceptions of servers as fat cats. Yet when a newspaper story relayed this characterization of large tips, only Agger intervened publicly with a blistering letter to the editor.128

Rather, union leaders were opposed to waitresses organizing outside of union structures, as this might interfere with worksite unionization, the basis of their locals, their membership dues, and their power. Their view was not unlike old-fashioned Gomperism, though their dislike of any alternative form of organizing – and by feminists at that – was also conditioned by the tight control by a largely male leadership of these unions, as well as their growing corruption. The Canadian here, Steve Tufts argues, became affiliated with mob interests in Canada – specifically, the Cotroni family in Montréal.129

In the United States, waitresses had a longer history with here, stretching back to the earlier 20th century when waitresses organized first as craft and sex-based locals, and after the 1930s, in mixed-sex locals. In some pro-union cities, at least half the waitresses were unionized. Women unionists carved out a separate political and bargaining space as a “sex conscious, occupational community,” shaped by their work culture, views of protective legislation, definitions of skill, and concepts of equality. Exercising a “semi-autonomous” place in here, they had reserved positions on the national executive board until the 1970s. In Canada, in contrast, wait staff was less organized and female membership was very small. Moreover, as Dorothy Sue Cobble points out, all servers in the United States faced union decline in the 1970s and 1980s as a result of the postwar Taft-Hartley backlash against unions, the growth of locations in the anti-union South, and especially the rise of the mass chain restaurant.130

What is revealing is the intensity of union animosity toward the wac, which was clearly a pressure group, not a raiding union. As Agger commented, it seemed as though the unions were “threatened” by the committee. In wac organizing notes about conversations with union leaders, words like “hostile, very unfriendly, angry” appear.131 The here affiliate referred to wac waitresses as “freeloaders” and “usurpers” because they did not recognize that the union represented them; they should just “pay up” their dues. The union refused to even sign the wac petition until the women joined a union: “they won’t support us until we support them by paying up,” stated the wac organizing notes.132

The here affiliate had other disagreements with the wac. The union leadership supported tipping out, claiming it was an accepted practice. It also rationalized low wages in the business by saying its members joined the union primarily for job protection and benefits, plus “all the tips they get.” There was only one solution, the union leadership told the wac: join the union and “they will look after us.” This paternalism was likely the response of arrogant men to “usurper” women, but it also emerged from the union’s top-down exercise of power.133

The Bartenders appeared somewhat less hostile, but their objections were similar: no organizing outside of their purview. The union was opposed to a wac member coming to its meeting to talk and, like here, condescendingly dismissed the women’s efforts as nothing new. The wac tried to explain that it was filling an organizing gap “because unions don’t and haven’t spoken for and represented all waitresses,” but the Bartender leaders insisted they should secure jobs through union membership.134 In the United States, waitresses had earlier benefitted from such “hiring hall” practices and portable union memberships; however, this was less likely to aid Canadian waitresses, whose work was transitory in a less unionized industry. It is revealing that other waitresses writing to the wac did not see unions as either sympathetic or a viable option. Commiserating with one letter writer, Agger pointed out that the Hotel and Club Employees Union did not protect its part-time workers, noting that the union representatives “tell us things like … what are you girls bitching about, you make all those tips (literally!).”135

“He seemed to be saying we should not lead ourselves,” was the rather astute wac comment about one union leader.136 Indeed, the unions’ suspicions of the wac reflected a broader dislike of any grassroots protests, especially from the left, which might challenge their leadership. They had reason to fear: feminism and demands for democracy often went hand in hand in unions.137 The principle of women’s grassroots self-activity so important to wfh and the strategy of garnering outside support from feminist, antipoverty, and community groups were also anathema to inward-looking unions. It is revealing that in 1978, the ofl women’s committee, chaired pro tem by Terry Meagher and including here leader William Kowalchuk, never discussed the tip differential.138

Meagher aside, there were some sympathetic unionists, but support was sporadic. In addition to a couple of union representatives at the London march, Bob Mackenzie also tried to intervene to aid the wacs relations with the ofl. Organized Working Women, as well as a Toronto cupe local, were more supportive of the wac’s efforts. However, the latter was a union with an existing, internal feminist presence. Some well-meaning, supportive feminist organizations like the Voice of Women kept telling the wac that the solution was to “organize a union,” but the Voices were unaware of how hostile the relevant unions were.139

Conclusion

The wac faded away later in 1978 when the differential seemed irreversible; as a subgroup of wfh, activists could turn their attention to other wfh priorities. Without financial and organizing support, the committee’s resistance could only continue for so long when wac members were also working at other jobs and when their one demand was a losing cause. In terms of building sustained resistance to capitalism, there were disadvantages to one-issue campaigns that were not able to build a wider, long-term organizational base. Writing to a northern Ontario group interested in the wac, Agger noted that the group “never had the finances and resources to propagandize as we wanted.”140 Her last letter to a waitress’ inquiry, in June of 1978, admitted that the wac was “quiet now” as the differential had been its “main subject of activity”; however, she pointed to its success in preventing a much-enlarged differential and offered to talk on the phone to the writer or come to speak to local waitresses.141

The waitresses’ predicament had some parallels with the Service, Office and Retail Workers Union of Canada (sorwuc) in British Columbia, although that organization had opted for a strategy of unionization. Nonetheless, sorwuc attempted to organize as a highly democratic and grassroots union with a feminist agenda and oriented to other community struggles. Like the wac, it embraced a philosophy of working-class women’s self-activity, with women defining what they needed, what they wanted, and how they would organize. Because sorwuc was outside the “official” house of labour, and a militantly feminist and socialist union to boot, it earned the approbation of the mainstream union leadership, which sanctioned raiding of sorwuc. In the end, sorwuc ran out of the energy required to fight employers, the state, and “fellow” trade unionists.142 Similarly, while union antipathy to the wac was undoubtedly shaped by its links to the feminist wfh, anti-left sentiments were also apparent; in the wac’s organizing notes, some unionists the members talked to denounced “Marxists” in the labour movement.143