Labour / Le Travail

Issue 92 (2023)

Article

“Lawless Coal Miners” and the Lingan Strike of 1882–1883: Remaking Political Order on Cape Breton’s Sydney Coalfield

Abstract: The Lingan strike of 1882–83 was the last in a series of strikes over a two-decade period on Cape Breton Island’s Sydney coalfield. With the use of untapped local sources, this article reconstructs the history of this understudied strike within a broader history of social relations on the coalfield. The migration of labourers from the island’s backland farms – predominantly from Highland enclave settlements – to the coal mines played a decisive role in shaping the era’s new coal mining villages and the character of social conflict. By the early 1880s, structural change associated with National Policy industrialism was eroding the old authority of the coal operators, and miners embraced the Provincial Workmen’s Association (pwa) to advance their claims in long-standing and highly localized contestations. Ultimately the coal communities themselves imposed the emergent trade unionism. The Lingan strike marked a transition to a new political order on the coalfield, structured by the place of the coal mines within the wider Cape Breton countryside and built upon a powerful localism and moral economy that recast the public sphere and the miners’ place in it.

Keywords: coal, mining, labour, strikes, riots, moral economy, capitalism, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

Résumé : La grève de Lingan de 1882-1883 était la dernière d’une série de grèves sur une période de deux décennies dans le bassin houiller de Sydney, sur l’île du Cap-Breton. S’appuyant sur des sources locales inexploitées, cet article reconstruit l’histoire de cette grève peu étudiée dans une histoire plus large des relations sociales sur le bassin houiller. La migration des ouvriers des fermes de l’arrière-pays de l’île – principalement des colonies d’enclaves des Highlands – vers les mines de charbon a joué un rôle décisif dans la formation des nouveaux villages miniers de l’époque et le caractère du conflit social. Au début des années 1880, le changement structurel associé à l’industrialisme de la politique nationale érodait l’ancienne autorité des exploitants de charbon, et les mineurs ont adopté la Provincial Workmen’s Association (pwa) pour faire valoir leurs revendications dans le cadre de contestations de longue date et très localisées. En fin de compte, les communautés charbonnières elles-mêmes ont imposé le syndicalisme naissant. La grève de Lingan a marqué une transition vers un nouvel ordre politique sur le bassin houiller, structuré par la place des mines de charbon dans la campagne élargie du Cap-Breton et construit sur un localisme puissant et une économie morale qui refondent la sphère publique et la place des mineurs dans celle-ci.

Mots clefs : charbon, mines, travail, grèves, émeutes, économie morale, capitalisme, Cape Breton, Nouvelle-Écosse

On 19 March 1883, union miners from various collieries across Cape Breton Island’s Sydney coalfield descended upon the mining village of Lingan, where the London-based General Mining Association (gma) had operated a colliery since the mid-1850s. Members of the Provincial Workmen’s Association (pwa) from Lingan had been on strike for more than a year, and the number of non-union coal cutters working the mine had slowly increased in recent months. On their way home from the colliery in the evening, the non-union labourers were confronted by the pwa delegation. A scuffle ensued. Anxious and angry yelling filled the air, perhaps echoing across the bay to be faintly heard in Bridgeport – another among the numerous coal mining villages that had sprung up along the east coast of Cape Breton Island over the previous two decades. The union miners routed their opposition and were reported to have engaged in acts of retribution into the night. By the morning, they had “full charge of the colliery.”1 Reports of the conflict soon appeared in the international press. The New York Times described the miners as “lawless.”2 Later, the London Times cryptically reported that “one hundred troops have been ordered to proceed to Lingan to preserve order in consequence of a riot having occurred among the miners in that district.”3

The collective violence of the miners at Lingan occurred amid shifting local loyalties that were reshaping the political order in Cape Breton’s “country of coal.” The gma’s mine manager at Lingan, Donald Lynk, was a central figure in the conflict, and his experience exemplified the changing political context. Lynk not only led the anti-union campaign but was also one among many Scottish Gaels who had come to the mining district from the nearby countryside, where “Highland enclave settlements” had developed out of the mass migration from the Hebrides and western Highlands earlier in the century.4 Migrants from these backland settlements occupied a central place in Cape Breton’s political economy of coal. But the old loyalties that had enabled Lynk to command their labour were clearly dissipating; Lynk was forced to retreat to shelter as the union miners took command of Lingan. While the pwa’s Trades Journal lamented that “some of the delegation” had “forgot themselves,” and warned its Cape Breton members to “never again” engage in violence, such forms of direct action were politically consequential and buttressed by a popular “moral economy” of the coal communities that would work to confirm the union presence.5

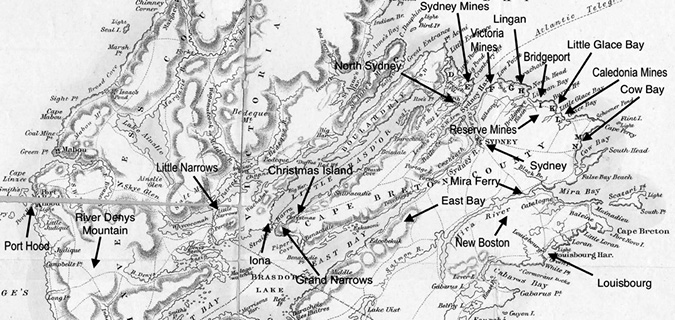

The Lingan strike of 1882–83 was the last in a series of strikes over a two-decade period on the Sydney coalfield. Though recognized as “one of the longest strikes in nineteenth-century Canada,” scholarly investigation has been limited.6 Historians have tended to view the strike as an event of fleeting historical significance – not much of a departure from strikes that had been broken by the gma in the preceding decades.7 A different judgement is offered here. With the use of untapped local sources, this article reconstructs the history of the Lingan strike within a broader history of social relations on the coalfield. It is a story that brings us to Sydney Mines and the emerging coal mining villages across Sydney Harbour near Lingan, such as Little Glace Bay, and that considers the relationship of these mining centres to the wider Cape Breton countryside (see Figure 1).

Central to this story is the large Highland population that developed at the mines from the coal boom of the 1860s, especially in and around Lingan, on the south side of Sydney Harbour.8 In the two decades before the Lingan strike, significant shifts in loyalties and orientations of political leadership within the reassembled Highland communities at the coal mines generated a powerful basis for popular agency, as a potent localism and established patterns of political brokerage and negotiation afforded miners significant influence.

Figure 1: Cape Breton Island, place names from the coalfield and countryside.

Source: Edward Weller, lithographer, Map of the Island of Cape Breton Compiled from Recent Surveys [detail with relevant place names added], 1868, Map 909, Beaton Institute Archives, Cape Breton University.

The coal bosses and their political allies suppressed trade unionism in the 1860s and 1870s, but in the early 1880s the structural context of National Policy industrialism and the arrival of the pwa created new opportunities. The “mercantile” political economy that Ian McKay ascribed to the Sydney coalfield in the “crisis of dependent development” of the 1870s was, in fact, significantly transformed only a few years later.9 National Policy industrialism connected the Sydney coalfield to Montréal’s coal market and revitalized and recast Cape Breton’s coal trade. With heightened demand for their labour on the coalfield, miners embraced the flexible institutional structure and mutualism of the pwa to advance their claims in a long-standing and highly localized social conflict.10 Feeling pressure to secure labour for their mining operations at Little Glace Bay, officials of the Glace Bay Mining Company forged an alliance with the pwa in defiance of gma efforts to drive trade unionism from the mining district. The new industrialism thus eroded old forms of authority, but ultimately the coal communities themselves imposed the emergent trade unionism. A new political order was in the making, built on a powerful localism and moral economy that shaped the public sphere of the coalfield and the miners’ place in it.11

I

The gma assembled a monopoly lease over Nova Scotia’s coal resources in the late 1820s, and the earliest phase of the industrialization of the Sydney coalfield soon followed. That this initiative had its origins in the efforts of a London jewellery firm to recoup money from the profligate Duke of York reveals the imperial cast of the gma’s activities.12 The association’s improved mining system at Sydney Mines was developed in the early 1830s and relied substantially upon the importation of skilled British colliers.

The mining works also drew labour from a colonial countryside that was expanding rapidly with the arrival of thousands of migrant-settlers from the Hebrides and western Highlands of Scotland. Largely because of this mass migration, which had effectively ended by midcentury, two-thirds of Cape Breton’s total population of 75,000 was identified as Scottish by 1871. The mining community at Sydney Mines had become substantially intermixed with families from the surrounding countryside as early as the middle years of the century.13

After the gma monopoly on Nova Scotia’s coal came to an end in 1858, the area to the south of Sydney Harbour underwent the most dynamic expansion on the coalfield, driven primarily by the demand for gas-coal in the urban markets of the American northeast. During the boom of the 1860s, Little Glace Bay and Cow Bay emerged as bustling mining villages in proximity to the gma’s mine at Lingan. Though the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty in 1866 undermined the profitability of the American trade, even greater investments were made afterward by coal companies seeking to link together new mines by rail with shipping facilities at Sydney Harbour. This expansionism created a new industrial geography of coal mining villages – including Bridgeport and Reserve Mines – fuelled by speculative investment and by labour from the island’s backlands.14

Labourers from backland homesteads were likely to have directly experienced the state’s expanding efforts to survey and regularize private property in land in the 1860s. In the many cases where legal title was lacking, the need to pay for land grants may have been a factor in directing some from the backlands to the mines.15 Whatever the individual circumstances of their migration to the mines, these labourers would collectively shape the social and cultural fabric of the new coal communities on the south side of the coalfield.

The expansion of the Glace Bay Mining Company’s mining operations in the early 1860s “brought an influx of people” to Little Glace Bay, including “many Catholics.” A Catholic church was built in 1865, and the village received its first resident pastor the following year.16 By the end of the 1860s, a local Caledonian Club had been established; at its annual meeting in Little Glace Bay, the “sports of the day” were “opened with an old fashioned Scottish reel.”17 Just on the other side of Little Glace Bay Harbour was the Caledonia colliery, established in 1865. Most of the first families at Caledonia were rural migrants from the Mira area.18 Highland migrants to the Lingan-Bridgeport–Glace Bay area soon outnumbered the longer-established Irish settler population in the vicinity of the mines and contributed to the creation of a Catholic majority in the new mining villages there.

At Cow Bay, the Presbyterian element was a clear majority; “our people began to flow in from the surrounding country and provision had to be made for their spiritual needs,” reported the Reverend John Murray. The presbytery’s application for land from the gma was granted, and a church was built in 1866 at a location between Cow Bay’s two collieries, the Block House Mines and the Gowrie Mines.19 The rural character of the mining village was readily apparent. Edith Archibald, whose husband, Charles, was mine manager of the Gowrie Mines, recalled livestock roaming the main street of Cow Bay. “Gaunt, long legged pigs and lean goats wandered about,” she wrote, “trying to find something to eat.”20

Labourers who arrived from the countryside to these new coal mining villages could expect to see familiar faces, relatives and friends. “Some folks say,” reported the Trades Journal in 1882, “that the whole of the Little Narrows has removed to Bridgeport.”21 Reports of labourers arriving in the spring and leaving for harvest in late August and September underlined the fundamentally rural context of the mines.22 These patterns meant that connections with nearby rural home communities were often renewed and that labourers remained ensconced within rural social networks as they travelled to work in the mining district.23

In the spring of 1862, Malcolm MacNeil wrote from Grand Narrows to William McDonald at Lingan: “let me know how is wages there this time.”24 McDonald was a schoolteacher who had relocated from the Grand Narrows area to the bustling mining village at Lingan about a year earlier. Already a potential interlocutor for rural men looking for work at the mines, by 1863 McDonald had moved to neighbouring Little Glace Bay, where he opened a store and acquired the position of postmaster the following year.25

McDonald was a Gaelic-speaker, Catholic, and young man of apparent prominence who would act as a political broker for the growing Highland-Catholic population in the Little Glace Bay area.26 He had arrived in the mining district with important affiliations from his home county of Inverness; Peter Smyth, the powerful Port Hood merchant and member of the House of Assembly, wrote to McDonald from Halifax in 1862: “Any thing that I can do for you here I will be most happy to attend to it.”27 McDonald also maintained ties to the Grand Narrows area, in part through the Christmas Island merchant Malcolm McDougall, who supplied him agricultural commodities such as flour, butter, and beef as well as shingles and boards. McDonald’s expansive network allowed him to collect debts in the countryside and to represent individuals making mining claims at Little Glace Bay.28 In 1865, he married Kate McDonald of East Bay, whose brother oversaw the gma’s company store at Lingan.29 McDonald thus operated from dense social networks that linked Little Glace Bay to places such as Christmas Island, East Bay, Grand Narrows, and Port Hood. The wider countryside was a significant factor in shaping the social order at Little Glace Bay, transferring webs of patronage, deference, and authority rooted in rural society to a new industrial context.

These patterns were decidedly those of the settler population and appear to have effectively excluded the Mi’kmaq from the labour force at the mines. The rural settlements or home communities that supplied the mines with labour were themselves settler-colonial incursions that had a deleterious impact on Mi’kmaw people.30 The Cape Breton Mi’kmaq responded to these conditions and threats of marginalization and erasure through an adaptive mobilization of skills and traditional practices, termed by Andrew Parnaby a “cultural economy of survival.”31 That we can find Mi’kmaq provisioning the mines with wooden pick handles and selling horses there suggests that this cultural economy provided a basis for Mi’kmaq participation in the economic activity generated by the mines.32 More broadly, however, the human geography and migration patterns associated with the new mining villages revealed highly segregated experiences that would shape emergent forms of class consciousness on the coalfield.

II

In early 1868, the social order at Little Glace Bay was challenged by a miners’ strike. Though the strike was apparently broken by the spring, conflict persisted into the summer.33 In May, the miners sent to James R. Lithgow of the Glace Bay Mining Company a list of grievances that had “led to a total Stoppage of All work in the mine.” Henry Mitchell, the mine manager, was the focus. In January, the miners claimed, Mitchell had promised to pay four dollars per running yard, but at the end of the month he paid the miners by the tub so as to deprive them of one-third of their wages. Later he sent them to work in “narrow places three in each place at a [still] more reduced price”; the colliers asserted, “we could not earn enough to support ourselves or our families.” After stopping work at the end of February, Mitchell resumed production on 18 March at reduced wages, promising a return to regular levels of pay at the beginning of the shipping season, which he also failed to do. Finally, in the winter and spring, Mitchell had promised the miners at Little Glace Bay that he would not employ new hands. Despite this promise, “he took on about thirty pairs of coal cutters.”

In May, Mitchell discharged all the new miners. The miners’ petition to Lithgow explains,

we occasionally met among ourselves to pass the time to talk about our circumstances and other social talk, and it seems that all other oppression on us by Mitchell was not sufficient to satisfy him or enough to make us Slaves altogether for on the seventh of May he discharged all the new hands, as we think to punish them and us for meeting and talking together at all. When we asked for the reason why he discharged the Men whom he was taking on a few days, and also had some men employed for work in a few days afterwards[,] he ordered us to bring up our picks, and stopped the work.

Mitchell viewed the mingling of the new hands with the Little Glace Bay colliers as a threat to his authority and sought to stave off any further meetings between the two.34 The colliers appealed to E. P. Archbold, general manager of the Glace Bay Mining Company:

We have a Union raised amongst us, which the Bos[s] has much Statements against, but we can assure you that it is for no bad design, but help another where sickness might occur or injured at his labour, and it is our intention to raise funds to aid one another.

We lay our suffrages before you hoping that you will consider our present position that we now stand in.

We solicit you as a gentlemen the rights of our labour.35

These petitions would have little impact. The recent end of the Reciprocity Treaty had greatly reduced access to important American coal markets. With the end of boom times, the miners’ bargaining position was significantly diminished. Indeed, it was Archbold who had thus advised Mitchell: “Coals are getting duller and cheaper in the U States. If they strike all we will have to do is to stop work.”36

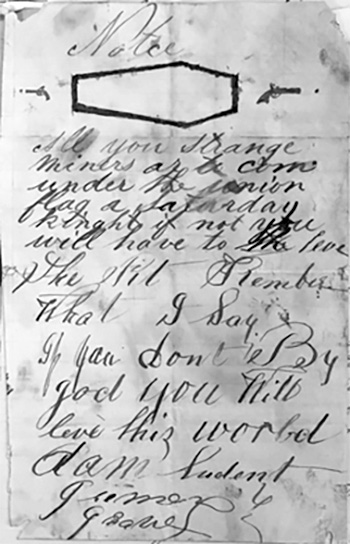

The deferential language of petition was a ritualized 19th-century form common in North American political culture.37 But the miners also spoke a far less deferential language. Anonymous notices threatening violence were posted in Little Glace Bay at the time of the strike. A number of these have been preserved in Henry Mitchell’s papers and reveal seething underground opposition. One notice, featuring a drawing of a coffin framed by two pistols at the top, declares, “All you Strange Miners ar to com under the union flag a Saturday kinght [night] if not you will have to le[a]ve the Pit[.] Remember What I Say[.] if you don’t By god you Will le[a]ve this world” (Figure 2). Another notice was addressed to someone named Morton, with a similar drawing of a coffin and pistol: “be wear your time is com[.] a fue Days to chang your ways is given.” Mitchell also received a threatening letter. Much of its contents have been cut out, but one can deduce its essence from the surviving bottom portion of the document:

i will blow heart out of you like a Squirel and Mitchel you Son of a Bitch I have got your Days nombered in my Brest and that is very few and i think it no more Sin to Sute [shoot] the like of you than a i would a dog for you are a son of hells fire and that will be your Distination [destination].38

This type of evidence presents to the historian “a sense of double vision”: deference and consensus on the surface, violent abuse and threats delivered in anonymity. As E. P. Thompson wrote of such apparent contradictions of expression, “both could flow from the same mind, as circumstance and calculation of advantage allowed.”39 The threatening letter was a “characteristic form of social protest” in a society “in which forms of collective organized defence are weak” and in which defiant individuals are vulnerable to “immediate victimization.”40 The anonymity of the threats directed at Mitchell and others was evidence of the vulnerability of the miners to the retribution of the coal operators and their allies.

Figure 2: Threatening notice, Little Glace Bay, 1868.

Source: Series A, Mitchell Business and Family fonds, mg 21.20, Beaton Institute Archives, Cape Breton University.

These allies included religious authorities at Little Glace Bay. In early June, local Catholic priest John Shaw and Presbyterian minister Alexander Farquharson Jr. prepared pledges for miners who promised never to attend union meetings again. Mitchell collected these, and they remain glued inside a tattered notebook – nine from Shaw and five from Farquharson.41 These clergymen had arrived in Little Glace Bay with the broader migration of Highland Scots from the Cape Breton countryside and were deeply embedded figures of religious authority in the community.42 The pledges they collected sought to absolve individual miners from prior associations with the union. An example of one, Farquharson wrote to Mitchell: “The bearer hereof Angus McPherson has I understand been a member of those Union Meetings but declares that hereafter he shall take no part whatever in them. I know Angus well and I feel that I can rely upon what he says.”43

Mitchell had apparently been sending miners to Farquharson and Shaw to make these pledges, but those sent likely complied only grudgingly. In one instance, Shaw complained to Mitchell, “send me none except those who are sincere and had made up their minds already.” “I care little for the stubborn Catholics who will never yield but because they cannot better themselves,” Shaw rumbled.44 Religious authority, in highly personal and direct forms, was drawn upon to reconcile the community to the prevailing social order at the mines.45

In September, a local man wrote to Mitchell from Sherbrooke, Nova Scotia, where apparently some of the miners had removed themselves. “I have Sean [seen] some of you[r] old hands hear[.] the[y] Spok very hard againce [against] you.”46 The miners were defeated, and some were evidently banished from Little Glace Bay. Nonetheless, the stubbornness Shaw encountered as well as the “reveries” of the anonymous threats, in which Mitchell was “a son of hells fire,” indicate that the restoration of consensus and deference were not inwardly accepted.47

III

The outcome at Little Glace Bay was a familiar one on the coalfield in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1864, troops had been dispatched from Halifax to break a strike at Sydney Mines. The police power of the state was swiftly mobilized once the miners threatened to shut down the pumps that kept water from overwhelming the mines.48 The Nova Scotia government also responded with draconian labour legislation, which included provision for up to a one-year term of imprisonment and hard labour for anyone who endeavoured to enforce a strike. In his speech before the House of Assembly in support of the legislation, Attorney General William Alexander Henry spoke directly to the situation of the striking colliers: “They are in possession of the houses that must be tenanted by the miners, but they will not leave them. Therefore it becomes necessary to teach them that the law is stronger than their lawlessness.”49 Samuel McDonnell, assembly member for Inverness County and brother-in-law of Port Hood merchant Peter Smyth, oversaw the removal of striking miners and their families from company houses – a decisive episode in the breaking of the strike.50

Yet, that the colliers had brought the strike to such an impasse was a sign of broader support in Cape Breton County. The Sydney Mines colliers had received relief from other mines and from “several Districts” of the county. The colliers also acknowledged the “contributions of the Yeomantry” during the strike.51 The long-time mine manager at Sydney Mines, Richard Brown, retired afterward to be succeeded by his son, R. H. Brown. In 1867, Richard Brown, writing as a gma director from London, advised his son not to employ a certain MacInnis, as he had been “one of the leading men at the meetings of the men during the Strike.”52 Father and son Brown, worried about the loyalty of the workmen, had long memories.

A decade later, in the context of a worsening depression in the coal trade, the gma sought to impose reductions at Sydney Mines. Another bitter strike resulted. Following evictions from company houses in early July 1876, the gma made vigorous efforts to bring in strikebreakers. The initiative was met with significant resistance. When nine men commenced work on the coal bank on 26 July, rifle shots directed at the bank rang out from nearby woods. One bullet allegedly came close to hitting R.H. Brown. The frightened coal fillers quit work. During the night, strikers let out coal from filled wagons, tore up railway tracks, and broke a mowing machine in one of the company’s fields. Two days later, a train bringing militia reinforcements and outside strikebreakers from Baddeck was fired upon. A man named Nicholas Tobin was hit in the back of the neck; significantly, he had been standing next to John Rutherford, the general manager of the gma. At night, the militia patrolled the company’s railway against further acts of vandalism. The strike was broken by early August. Those wishing for their jobs back were compelled to individually call upon the mine manager in his office. By 2 August, about 150 men had agreed to work on the manager’s terms; 30 others were refused re-employment.53

R. H. Brown’s notes of these events includes a blacklist with detailed categories. The fathers of the driver boys who initiated the work stoppage in late May made the list – “chief men whose boys stopped work” – as did “workmen for whom warrants were issued” in June. Most names fell under the more capacious heading of “objectionable men.” Brown also took note of those who supplied the miners with money during the strike, which included North Sydney merchants Vooght Bros. and W. H. Moore.54

The sympathies of local magistrates and merchants for the miners caused gma officials considerable displeasure. The London directors decided to reopen a company store at Sydney Mines for the specific purpose of punishing local merchants.55 And despite the offer of a considerable reward from the gma, the individual responsible for shooting Tobin – a possible assassination attempt, some suspected – was not identified.56 After two gma hay barns were burned to the ground in the aftermath of the strike, the gma’s Halifax agents judged it hopeless to identify the culprits.57

The political isolation of the gma was telling of broader developments that challenged the old loyalism to the mine manager. The rapid expansion of the mines on the south side of Sydney Harbour also reconfigured the gravity of political and economic power on the coalfield and further removed it from gma paternalism. William McDonald at Little Glace Bay was part of a growing stratum of merchants in the mining communities who were independent from the coal operators. By 1871, he was listed in the provincial directory as “postmaster, telegraph operator, and dealer in dry goods, groceries, [and] provisions.”58 McDonald had facilitated opposition to the early efforts of E. P. Archbold to establish a de facto company store monopoly over trade at Little Glace Bay, and McDonald’s brother-in-law, Ronald McDonald, had purchased the gma’s store debts at Lingan.59 While Henry Mitchell might command local loyalties when faced with a strike in 1868, the power of the mine manager was far from absolute.

In the 1872 Dominion election, Cape Breton County had become a two-seat constituency. William McDonald ran as an Independent Conservative on a ticket with Sydney barrister Hugh McLeod, son of the Reverend Hugh McLeod, a prominent Presbyterian minister who had ministered and developed coal properties in the Mira area.60 The ticket was an effort to unite the Highland vote along interdenominational lines and reflected both the demographic significance of that population and the increased importance of the new mining communities. McDonald was elected along with the government candidate, N. L. McKay. Following McKay’s departure from the Conservative Party in the wake of the 1873 Pacific Scandal, McDonald and McLeod ran as government candidates, and McDonald was re-elected.61

Though miners were substantially disenfranchised from the vote by property qualifications, their place in the new coal communities made them a significant political factor, and McDonald could not afford to oppose them.62 But in the wake of the defeat at Sydney Mines and a depressed trade in the later 1870s, social conditions in the mining district were grim. Father Shaw reported to McDonald in February 1878 that “little or nothing is doing in any of the mines.” At the Reserve and Gardiner mines, wrote Shaw, “a large number of the population are said to be in a starving condition.”63

As the deepening depression in the coal trade brought social crisis to the mining district, John A. Macdonald’s National Policy arrived as potent political capital. William McDonald’s most substantive speeches in the House of Commons were about the National Policy and the need for a coal tariff.64 In politics, he acted as a loyal defender of the mining district. The McDonald-McLeod ticket prevailed in 1878. After Hugh McLeod’s unexpected death, his brother, Dr. William McKenzie McLeod, was elected in a by-election in 1879 to fill his place. William McDonald’s political support was based on dense social networks that straddled the countryside and Little Glace Bay, consolidated by patronage and personal favour. “I am glad to see that your high position in life did not make you too proud to look after the er[r]an[d]s of the less favoured,” wrote one constituent to McDonald in 1873.65 His politics combined claims to ethnic and religious representation with the class politics of the National Policy.66

IV

Influenced by the lobbying of Nova Scotia’s colliery owners, in 1879 the Conservative Party imposed a tariff on imported coal as part of its National Policy, a program of colonial nationalism that included the incorporation of the province’s coalfields into a new industrial political economy.67 In that same year, the Provincial Miners’ Association was founded at Springhill.

The man behind the association was Robert Drummond. A grocer’s son, he left Greenock, Scotland, around 1865 for Cape Breton. He settled initially at Lingan, where he first encountered Donald Lynk, then a bank boss.68 With work at the mine irregular, Drummond moved along to the “Roost Pit” at Little Glace Bay, presided over by Henry Mitchell. Drummond later returned to Lingan to set up his own store, but the dearth of cash on offer in the locality to pay for goods caused him to leave once again. Around 1872, he left Cape Breton for mainland Nova Scotia. By 1879, he was himself a bank boss at Springhill. When the Spring Hill Mining Company imposed two consecutive reductions on the miners, Drummond published a letter in the Halifax Herald denouncing the company’s policy as an unjustified effort to enhance dividends. He consequently lost his job. The miners at Springhill formed the Provincial Miners’ Association on 29 August 1879. Drummond, who was considered a hero for his stand, was appointed grand secretary of the new association and would become its most powerful officer. Despite evictions from company housing, the miners won the strike. The victory greatly enhanced the reputation of the new union.69

In January 1880, the association commenced publication of a weekly paper, the Trades Journal, and later in the year changed its name to the Provincial Workmen’s Association, signalling that its organizing efforts were not to be limited to miners alone. The regalia, titles, and rituals of the pwa were modelled on a fraternal order, and the association was organized by a series of lodges, broadly similar in its form, flexibility, and emphasis on mutualism to the contemporaneous Knights of Labor.70 In 1879, soon after the victory at Springhill, lodges were formed in Pictou County at Stellarton, Westville, and Thorburn.71 The following spring the pwa’s grand council empowered Drummond “to make arrangements for drawing Cape Breton into the union.”72

Reports in the Trades Journal made clear that the gma’s victory over the miners in 1876 still reverberated across the Sydney coalfield. The blacklist developed from that strike had been circulated to other coal operators and continued to be enforced.73 And workers, it was claimed in a letter to the editor signed “Cape Bretonian,” required a “ticket of leave” in order to obtain employment at a neighbouring colliery.74 A Cape Breton correspondent reported in the summer of 1880 that “while nearly all are in favor of a Union, none come forward to begin the business.” The workmen were even afraid to subscribe to the Trades Journal, though it was “eagerly read.” The collieries in Cape Breton were thoroughly “Boss ridden.”75

Conditions at the mines were also illustrated by the Trades Journal in what was likely meant as a character portrait of Donald Lynk, the gma’s mine manager at Lingan. This “wee cork,” a petty boss “having risen from the ranks of the working men,” was presented as an uncouth, rural Gael and a “pompous little man of the ‘Lochaber no more’ persuasion”: “From being a driver of horses, he was promoted to drive men, and he became … adept at it[,] though at first from his imperfect knowledge of languages, he used to confound English with big Bras d’or and Baddeck gaelic, and any Inverness man knows, what such a mixture would produce.”76 While such an account reveals the capacity of coal operators to recruit and cultivate loyal bosses from the surrounding countryside, it also suggests the hand of the paper’s editor, Drummond, in drawing on personal experiences and prejudices in depiction of the Cape Breton situation.77 The tyranny of the coal operators, according to Drummond’s improving worldview, undermined the manliness and independence of the workmen and defied British rights and freedoms. Lynk would become the exemplar of this defiance of British tradition in the Trades Journal. The paper proclaimed, “the boast contained in the line ‘Britons never shall be slaves’ must be looked upon by many of the Britons of Cape Breton as a lieing [sic] satire.”78

Political and economic conditions on the Sydney coalfield, however, were in considerable flux. Under the National Policy tariff, the Cape Breton coal trade was reoriented toward the St. Lawrence market and experienced a dramatic recovery. Already in 1880, coal shipments “far exceeded any season since 1873.”79 A correspondent from Reserve Mines reported that work was “pretty busy” at all the mines, and in July, some managers agreed to pay increases – perhaps motivated by a desire to avoid the formation of local lodges.80 But at the Gowrie Mines, the restoration of old rates – by one cent per box – was refused, and the manager warned the miners to steer clear of the union.81 R. H. Brown also called together some of his workmen at Sydney Mines to warn them against affiliating with the pwa.82 Enquiries from Cape Breton about forming lodges on the island had nonetheless already been made.83

The expansion of the coal trade continued. By 1881, the St. Lawrence ports, principally Montréal, had clearly become the most important market for Cape Breton coal. Total coal sales from Cape Breton County reached 516,852 tons – essentially double the amount that had been shipped only two years earlier.84 The rise of the St. Lawrence trade constituted a dramatic transition in the political economy of coal and included a consequential shift from sail vessels to steamships in the transport of Cape Breton coal.

Amid this revival of the coal trade, in the summer of 1881, Drummond arrived in Cape Breton on an organizing mission accompanied by William D. Matthews, formerly of Caledonia Mines. Given the personal acquaintance of the Cape Breton–born Matthews with the miners at Caledonia, the pair commenced their mission there. Notices of a meeting were “posted around the works at various points,” and Drummond and Matthews spoke of the many concessions “secured on the mainland” before the “largely attended meeting.” The attendees decided to form a pwa lodge in defiance of the contrary pleas of the mine manager, David McKeen.85 The manager at Reserve Mines, D. J. Kennelly, had sought to pre-empt such an outcome, summoning the labourers at the colliery to hear his anti-union speech. However, the miners had met in advance of the manager’s oration to decide on a course of action. They marched together to the hall and openly declared their intention to join the union.86

Drummond recalled that his plan was to organize the “southern collieries” before Sydney Mines, where strong resistance from R. H. Brown was anticipated. The strategy worked. By the time Drummond and Matthews arrived at Sydney Mines, “the union contagion had spread,” and “a union was formed without any opposition.”87 Thus, before the end of July, lodges had been formed at Sydney Mines (No. 8 Drummond), Bridgeport (No. 9 Island), Reserve Mines (No. 10 Unity), Caledonia Mines (No. 11 Equity), Gowrie Mines (No. 12 Banner), Block House Mines (No. 13 Eastern), Little Glace Bay (No. 14 Keystone), and Lingan (No. 15 Coping Stone). A Cape Breton subcouncil of the pwa was also created. By the fall, a lodge at the Ontario Mines in Big Glace Bay was established as well (No. 16 Wilson). The pwa by then claimed a total of 1,297 individual members on the Sydney coalfield.88 Suddenly, within a few months, the majority of the pwa’s membership was in Cape Breton.

The decision of the pwa’s Cape Breton subcouncil to designate Little Glace Bay as the site of its meetings underlined the shift of gravity on the Sydney coalfield, away from Sydney Mines, to the south side of the coalfield.89 The rural context of the mines played a foundational role in shaping the character of the coal communities here, and it also shaped the social and cultural underpinnings of the new unionism. Of 71 Cape Breton pwa officers identified in the Trades Journal, nearly one in three had the surname McDonald (11), McLeod (6), or Ferguson (5).90 With these developments, the mythical “loyalty” of the Highlander was recast and celebrated in the pages of the Trades Journal to reinforce union solidarities.91

The sudden rise of the pwa in Cape Breton revealed the highly fragile and attenuated local rule of the coal operators. “One thing remarkable about the movement in Cape Breton is the sympathy expressed by both farmers and merchants for the success of the Association,” reported the Trades Journal, as both groups wished to see miners “draw their pay out of the office without being stopped in some of the truck stores.”92 Meanwhile, in the midst of the pwa’s organizing success, the priest who had in 1868 aided Mitchell in driving trade unionism from Little Glace Bay was depicted approvingly in the Trades Journal as a stalwart of the community. A correspondent from Cape Breton thus reported on Father Shaw’s removal from Little Glace Bay to mainland Nova Scotia: “General regret is expressed at the removal of the Rev. Mr. Shaw from Little Glace Bay, where he officiated as parish Priest for the past fifteen years. He was loved and revered by his parishioners, and as a man he was respected and esteemed by all who knew him. He was a thorough advocate of temperance, worked diligently for the cause, and was the main stay of the ‘League of the Cross’ in his parish.”93 The pwa was hardly a centrally administered body but rather a loose confederation of lodges, driven and shaped by local agency and perspectives.94 The League of the Cross – the Catholic total-abstinence society with which Father Shaw was deeply involved – gained an important local following and advocated an improving mission that was not entirely unlike that embraced by Drummond.95 The pwa channelled traditional sources of local authority at Little Glace Bay; it did not rival them.

V

At Lingan, however, signs of the gma’s bellicosity soon emerged. On the heels of the dramatic expansion of the pwa, Donald Lynk announced in December 1881 that he would require all his workmen to sign a document pledging no involvement with the union. A letter writer from Lingan reported on 12 December that “we have a Judas, a treacherous fellow or two in our army.” Someone had been carrying information to the boss.96 Two members were subsequently expelled from Coping Stone Lodge, one of whom had signed Lynk’s document. But Lynk’s request was widely refused. Though the immediate significance of the emerging conflict was diminished by the fact that the shipping season had closed, as several of the workmen left Lingan “for their homes in the country,” tensions on the ground soon revealed themselves.97 A man named John McDonald, a Lynk ally nicknamed “Smoker” in the Trades Journal, declared in the presence of Coping Stone Lodge members that “it was no harm to kill a union man” and later reportedly smashed a window of the lodge. McDonald was subsequently assaulted, struck on the back of the neck. Lynk and McDonald travelled to Sydney to bring charges against the persons accused of assaulting McDonald, but the charges were dismissed.98 N. L. McKay, defeated as a Liberal in the 1878 Dominion election, represented the defence and was thanked by the workmen “for the able manner in which he defended the men lately charged with common assault.”99

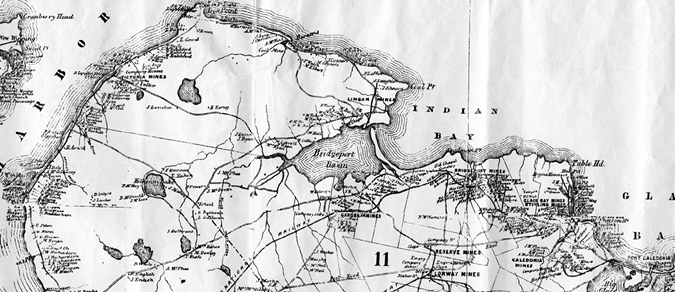

Figure 3. Lingan and environs, south side coalfield.

Source: A. F. Church, Map of Cape Breton County [detail], 1877, Beaton Institute Archives, Cape Breton University.

After work at the mine resumed in February, fifteen men were dismissed “on account of their connection with the lodge.”100 Members of Coping Stone met with Lynk and requested that they be allowed to share work with their unemployed brothers. Lynk rebuffed them.101 A document among Henry Mitchell’s papers, addressed to Lynk and dated 1 March, presents the miners’ demands. The first was for work to be shared with unemployed lodge members. The second demand was that those who departed from the lodge “must be put from their work as they have been the Instigators of much trouble.” The document concludes: “Without Complying with the above wishes, there will be a suspension of work on the 8th of March 1882.”102 The strike would begin then.

The designation “McLynk” for Donald Lynk in a letter from Lingan published in the Trades Journal seemed to hint at a perception of the manager’s network of allies as Highland relations.103 Michael McIntyre was expelled from Coping Stone Lodge for “misconduct” but, as a correspondent from Lingan reported, “found a refuge in Donald[’]s arms.” Though Lynk had apparently forbidden the raising of pigs in the mining village, McIntyre was allowed to use a company house as a pig pen, while houses were in demand among union miners.104 Lynk was also regularly called “Donald Pasha” in the pages of the Trades Journal – another ethnic other, decidedly beyond the pale of British civilization. By the end of March, Lynk had reportedly sent letters “into the country offering heavy inducements to come and work.” The Trades Journal continued:

Two men came along, but seeing how matters stood they went over to Little Glace Bay. Thereafter, other three came who had worked in Lingan last summer. On going to see D.L., he told them to go to work and he would protect them. He asked one of them to go back home and endeavor to induce more men to come, and promising to give him $4.00 if he secured a pair of men, or $20.00 if he secured two pairs.105

Lynk’s strategy achieved limited success. The previous summer, R. H. Brown spearheaded the formation of the Cape Breton Colliery Association (cbca) to unify the coal operators against the pwa.106 But Lingan miners nonetheless found employment at Little Glace Bay, in defiance of cbca efforts.107 The secretary of the cbca wrote to the Glace Bay Mining Company to protest its employment of “Lingan men.” James R. Lithgow, a company director, considered the cbca’s request “a piece of gross impertinence.”108

Lynk and the gma were also looking elsewhere to recruit labour. At Lingan, Presbyterian service was delivered by the Reverend John Murray, of Sydney’s Falmouth Street Church, in “one end” of a gma house. At neighbouring Low Point, Lynk provided use of “a whole Company house” to Murray and local Presbyterians.109 Lynk’s life membership in the British American Book and Tract Society is suggestive of his religiosity and connections to Presbyterianism.110 He certainly had an ally in Rev. Murray, who would travel to Scotland to accompany miners recruited there by the gma to work at Lingan. Given the Catholic majority in the Lingan area, Murray’s initiative likely acquired sectarian meaning. But the gma’s London board were the ones truly initiating these moves. gma director Richard Brown wrote to his son and mine manager at Sydney Mines, R. H. Brown, in early April. He explained that C. G. Swann, the gma’s secretary, “is sending out 40 Colliers for you. I hope they will turn out well. You must keep them out of the Union.”111

Robert Drummond was also in Scotland at the time. He happened to be aboard the Canadian with Murray and the recruited miners as it travelled across the Atlantic to Halifax. Drummond engaged in conversations with the miners for several days before Murray realized what was going on. Upon arrival in Halifax on 4 May, Drummond telegraphed news that the Scottish miners had left for Sydney and Lingan on the Alpha.

Numbering more than 30 miners and over 60 people in all, as several miners travelled with families, they were mostly from the mining county of Lanarkshire, plus a few from Fife. When they arrived at Lingan on 6 May, they were met by the members of several pwa lodges as well as by Lynk, R. H. Brown, and fourteen constables called in to protect them. Protection was unnecessary. The imported miners joined the union.112 Upon hearing the news, Richard Brown lamented the behaviour of “those scoundrels of Colliers from Scotland,” claiming never before to have witnessed “more dishonest or more disgraceful conduct on the part of workmen.”113

R. H. Brown had sent an urgent telegraph to James A. Moren, president of the Glace Bay Mining Company, in Halifax: “Thirty seven Scotch miners who our company have imported at much expense have joined Union and refuse to work for us. I request that you order your manager Glace Bay refuse employ them.”114 The company again defied Brown and the gma. “Mr. Brown will get no comfort from us,” declared Archbold, who offered instruction to Mitchell on 9 May: “If you want men take them.”115 The Trades Journal reported just over a week later that the miners had left for “Little Glace Bay where they all received employment.”116 Mitchell complained that the move had made him a “black sheep” among the coal operators.117

The Glace Bay Mining Company’s defiance of the gma and cbca was powerful. In fact, the company had directly aligned itself with the pwa, and its directors had intervened to ensure that the Nova Scotia Legislative Council assented to the pwa’s incorporation.118 In January, the company had rejected the cbca’s offer to enter into an arrangement with the cbca collieries, whereby 50 cents per ton was to be pooled on coal sales and redistributed among the members on the basis of 1881 sales.119 The arrangement was clearly designed to subsidize the gma’s fight against the pwa. Lithgow explained to Mitchell in early May, “we have made our choice + have chosen the P.W.A. rather than the C.B.C.A.” Lithgow not only considered the pwa “a first rate institution” that “was necessary to get justice for workingmen”; he also noted that without the pwa’s aid, the company would have been unable to ship tens of thousands of tons of coal to the Montréal market, “for we would have been afraid of not getting men to give steamers dispatch.”120 When the company hired steamships on time charters to deliver large quantities of coal to Montréal buyers, rigorous and steady operation of the mines was necessary to fulfill contracts and to avoid having a costly chartered steamship lay idle. This was precisely the case in March 1882, as the company contracted to deliver 30,000 tons of coal to Montréal – an aspect of the new economic leverage available to the miners under National Policy industrialism.121

Mitchell was not pleased about the arrangement the directors had worked out with Drummond and the pwa, and he expressed concern that he was being superseded as manager.122 But the pwa was better able than the cbca to secure reliable coal production. Drummond co-operated with the directors and was treated as an adviser to the company.123 Responding to company concerns about maintaining a steady supply of labour, for instance, the Trades Journal criticized the tendency among the miners to take a day or two off following payday.124 In 1882, the Glace Bay Mining Company employed twice the number of coal cutters than the previous year and shipped more than 70,000 tons – well over double 1881’s shipments.125

William McDonald played a significant role in supporting the company’s operations as well. He exercised his influence in Ottawa to make sure the St. Lawrence was sent ahead to deepen Little Glace Bay Harbour before Port Caledonia, the harbour of the rival Caledonia Coal Company, whose president, David McKeen, was a cbca member.126 In a limited shipping season, this work was highly time sensitive and important to the successful operation of the colliery. “Our friend Mr. William McDonald, MP, to whose influence with the Government we are indebted for the dredge’s services … leaves for home tomorrow,” Lithgow wrote to Mitchell on 18 May. He added,

He saw Mr. Moren and me this afternoon + we both acknowledged to him our indebtedness + promised him our support at the next election. … The P.W.A. in Cape Breton feel grateful to you + us for taking on those Scotch miners, + also must feel that but for me their Act of Incorporation would not have got through the Council, + I feel sure they only want the opportunity to return the compliment + show their appreciation of our friendship by voting for Mr. McDonald, the friend of the Little Glace Bay Colliery.127

McDonald’s support of the coal company included a social mandate, shaped by the wider coal community. He proclaimed his hope for increased wages for the miners in Parliament.128

In the Dominion election contest of that June, McDonald and William McLeod ran together on a Conservative ticket for Cape Breton County. N. L. McKay, who had successfully defended the men charged with common assault by Lynk earlier that year, ran as a Liberal. However, the main rival to the McDonald-McLeod ticket was another pair of Conservatives, Edmund Dodd and Malcolm McDougall, the Christmas Island merchant. Dodd, an attorney for the gma, was especially maligned. Descended from a prominent Loyalist family in Sydney, Dodd, readers of the Trades Journal were told, “claims to be a member of the English Aristocracy.” He was, in short, “the nominee of the C.B.C.A.” Assimilating ethnic and class loyalties, the Trades Journal declared, “Every real scotchman, and every sound Irishman will make a straight square vote for McDonald and McLeod.” While it was accepted that Liberal workmen might vote for McKay, the Trades Journal strongly opposed “the Dodd faction.”129

The results of the 20 June election were mixed. McDonald headed the poll at Lingan and Glace Bay and won with even larger margins of victory in the outlying rural districts of East Bay, Sydney Forks, and Grand Mira, reflecting social and political networks that straddled rural settlements and coal communities. Dodd’s strength in North Sydney and Sydney Mines was perhaps evidence of the persistence of the old loyalism, but it may have also stemmed from his opaque and shifting affiliations; he had provided legal defence for the miners in the 1876 Sydney Mines strike. McDonald finished first and Dodd second. Both men were elected.130 Even in an era when many did not meet the property qualification required to vote, miners were a factor in electoral politics on the Sydney coalfield and were universally courted by politicians. The extension of the franchise was also identified as a political priority in the context of the strike. From Little Glace Bay, “A Miner” wrote, “There is beside co-operation another thing that is necessary for us as a class to obtain before capital will recognize the workingman as a power, viz: – the extension of the Franchise to the working class and the only means we have at present is to get up an agitation in that direction.”131 The extension of the franchise to miners living in company houses, granted in 1889, would become one of Drummond’s principal lobbying achievements.132

Celebrations of the second anniversary of the pwa, held on 2 September 1882 and detailed in the Trades Journal, signalled a new public presence for the miners in Cape Breton County. Union loyalties that had been forced underground in earlier decades were now openly and widely vaunted, and they were powerfully shaped by Highland cultural forms and symbols. At Cow Bay, members of Eastern and Banner Lodges assembled and marched in procession to welcome lodges from Little Glace Bay (Keystone) and Big Glace Bay (Wilson). “So enrapturing was Scotland’s favorite melody to whose note they marched, that the countryman is excusable who mistook them for a rising clan who had substituted the uniform blue for the Tartan.” Joining with the Glace Bay lodges about a mile outside the village, the members of the four lodges proceeded together through the Gowrie Mines and the Block House Mines before assembling on the picnic ground.133

At Caledonia Mines, 100 members of Equity Lodge gathered and “formed into a procession and marched gaily from thence to the invigorating strains of [a] highland pibroch,” through the “manager’s beautiful park, then to Bridgeport.” Here, the procession was joined by members of Island Lodge as well as the Reserve Mines lodge (Unity). The enlarged procession of about 450, clothed in pwa regalia, carried on through the Lorway Mines before arriving at Reserve, where several platforms had been erected in an open field. On these, the men with their “wives, sweethearts, cousins and aunts … danced to the best music the Island of C.B. could furnish.” At 12:30, the group moved to a hall where “the tables groaned under a bountiful supply of the good things of this life”; later, the manager, D. J. Kennelly, paid a visit and was “well pleased with the deportment of ‘his boys.’” Members of Equity Lodge departed afterward in order to attend a “grand ball” at Little Glace Bay that lasted until 9 p.m.134

Exactly three weeks later, Drummond Lodge celebrated its first anniversary at Sydney Mines and North Sydney. A procession of 250 members of Drummond Lodge, along with members of some of the other lodges, was gathered. A correspondent reported the scene:

The order of the march was two deep. First came four pioneers followed by the ‘drum and fife’ corps, next our country’s flag, the Union Jack, next officers of lodge, next a body of at least 100 Brothers, next and near to centre, our banner borne by four bros. with the words ‘Drummond Lodge No. 8 of P.W.A.[’] on one side, and Unity, Equity, and Progress, on the other side. Close by marched two of our native pipers, who well performed their part, followed by the remainder of procession in the midst of whom were two more of our native ‘sons of heather’ with their bag pipes.

The procession moved to Albert Corbett’s storefront, where “three deafening cheers” were given to the sympathetic merchant before the group continued on to North Sydney. Here, the streets were crowded with spectators. W. H. Moore & Co., supporters of the miners in the 1876 strike, had set up a line of flags for the occasion, one of which was stamped “success to the P.W.A.” Three cheers were made for this mercantile enterprise. The group then returned to Sydney Mines to gather at the Temperance Hall, where three platforms were set up for dancers “young and old,” “treading time to the rich violin music of Messrs. T. Ling and J. Nicholson, and to the music of the pipers.”135

The place of the fiddle, pipes, and step dancing at these gatherings revealed ways in which Highland cultural traditions became integrated into the common culture of the coal country. Support from local merchants and sympathetic mine managers, as well as associations with British loyalism, confirmed the sense of a stable and powerful pwa presence. And the processions through the coal villages carried considerable symbolic importance as a claim upon public space. This was the environment that sustained the Lingan strike. The Glace Bay Mining Company had agreed to take on workmen from Lingan as Drummond operated, in effect, as adviser to the company; the Cape Breton pwa lodges contributed to a fund to support the strikers; and William McDonald accommodated the Glace Bay Mining Company and the prevailing feeling on the ground.136 The miners and the pwa commanded considerable local strength.

VI

The organizational tactics of the pwa – specifically, direct negotiations between individual lodges and pit bosses – were not ideally suited to confronting the gma. The Lingan mine was yielding only a “small profit” at the time of the strike, and the gma had recently, through a third party in Halifax, purchased the Victoria Railway to connect its nearby mine at Low Point with shipping facilities at Victoria Wharf, which the gma was having rebuilt throughout the summer by a “large force of men.”137 The gma was, in effect, preparing to shift production from Lingan – barely profitable after three decades of coal production – to its new works at Low Point, Victoria Mines. This calculation informed the gma’s hard-line stance. “It is of little consequence whether the Lingan Mines are idle or not,” Richard Brown advised his son. “I would never concede the fraction of a Cent to the Men but fight it out to the bitter end.”138 In December, the gma was “preparing to move nine blocks of workmen houses to the new works at Low Point,” while the remaining 60 houses at Lingan were mostly “uninhabited save for mice or rats.”139 “As you say it will be much better to fight the battle with the Union at Lingan than at Sydney [Mines],” Richard Brown wrote approvingly to his son.140

For the gma, then, the strike was unambiguously about control. Union miners had received eviction notices in the spring of 1882.141 Those remaining sustained themselves during the summer with the help of a plentiful herring fishery and cod.142 By September, a contingent of only 31 individuals was left. “Supplies are not sent as regularly as they should,” reported the Trades Journal, “yet the brothers are stout hearted. The strike is still on.”143 Sydney physician and William McDonald’s brother, Dr. Michael A. McDonald, also made calls at Lingan to attend to the remaining people there free of charge.144 However, it was clear no resolution was in sight, and the gma was not interested in suggestions from the union miners to submit the case to the government for arbitration.145

Meanwhile, by November rumblings about Lynk’s intentions to move men from Low Point to Lingan were heard.146 In January, Lynk indeed made efforts. Nine men were sent from Low Point to work at Lingan, but they were “captured by the union” and returned to Low Point.147 Later, on 25 January, six more men working at Lingan were captured by a union delegation.148 R. H. Brown was scandalized. The group of “50 or so Unionists” had entered the enclosure around the pit at Lingan, ignoring “a notice at the gate prohibiting any person going there without permission of the gma or their Agent.” Brown subsequently interviewed Drummond Lodge delegates who had participated in the Lingan excursion on direction of the pwa subcouncil. “I told them to warn all the men whom they represented that I would prosecute any man who entered upon any of the gmassn property at Lingan,” he fumed.149 By month’s end, it was reported that seven pairs of men were working the pit along with two or three loaders.150

These episodes of direct action by the miners coincided with indications of the faltering alliance between the Glace Bay Mining Company and the pwa. When Henry Mitchell and Walter Young of Lingan competed for a seat on the county council in November 1882, the Trades Journal came out strongly for Young and against Mitchell, whom the paper described as “Anti Union at heart. He was selected as the strongest man to oppose the union party. The managers think he may draw some union votes.”151 Mitchell won the seat with a wide margin of votes from Little Glace Bay; the Trades Journal viewed the outcome as misguided parochialism.152 Lithgow had by this time begun to question his relationship with Drummond.153 By February, the directors were considering joining the cbca, though in the end the company decided against it, much to the consternation of Mitchell.154

Lynk and the gma persisted in their efforts to find workmen to send to Lingan. John McKinnon, a tailor in Sydney, reportedly tried to recruit a man, returning to Little Glace Bay from the country, to work at Lingan for $2 per day. The man, Michael McMullen, was a member of Keystone Lodge, and he wrote to the Trades Journal advising miners not to frequent McKinnon’s shop and warning that Lynk had other agents in Sydney trying to recruit.155 About 45 men were employed at Lingan by mid-February, but the Trades Journal emphasized that the figure did not include many coal cutters.156 Meanwhile, a correspondent reported that Lynk’s office clerk, Alex McDonald, had come to Glace Bay on a Sunday, 25 February, “under the influence” and hurled abuse at passersby, who all ignored him, and brandished a revolver. Lynk’s men, complained the correspondent, “will come to Glace Bay and we never meddle with them, and then they will boast in Lingan that we were afraid.” This behaviour was at the instruction of Lynk, who advised his men “to be as saucy and insulting as possible to union men.”157 By March, some of the old hands began to return to work at Lingan.158

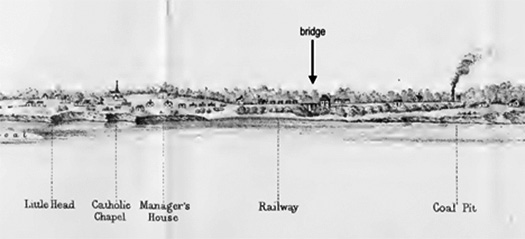

A party of about 70 miners descended on Lingan on 19 March from Glace Bay, Reserve Mines, Bridgeport, and Sydney Mines.159 This was not spontaneous. The order had come from the Cape Breton subcouncil of the pwa for each lodge to send fifteen men to Lingan in order to persuade the labourers there to quit – some of whom, the Trades Journal claimed, hoped the arrival of a union delegation would give them a needed pretext to leave their work.160 By six o’clock that evening, the party of union miners occupied the “big bridge,” over which those working at the colliery had to pass to arrive back at their houses (see Figure 4). Lynk, Brown, and Constable Musgrave accompanied the men attempting to cross this railway bridge. John McDonald – the Lynk loyalist “Smoker” – also accompanied the gma group and ordered the union men to move off the bridge. One of the strikebreakers reportedly drew a gun. A fight broke out. Lynk’s men were outnumbered, and Lynk was struck. Some were knocked down and kicked, others scattered. The siege continued into the next day, by which time the union men had taken “full charge of the colliery.”161

Figure 4. Lingan.

Source: “The North Shore of Lingan or Indian Bay” [detail], in Richard Brown, The Coal Fields and Coal Trade of the Island of Cape Breton [London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, 1871], back matter.

A telegram was received at Halifax, sent from the gma’s Lingan office, reporting on what had transpired. It served as the basis of news reports that appeared in the Canadian and international press. The New York Times, under the breathless headline “lawless coal miners,” quoted from the telegram at length:

The engineer and blacksmith were badly kicked. Several others, including the manager, were struck. After night-fall the rioters increased in numbers, visited the workmen’s houses, breaking several doors, dragged men out of the houses and beat three of them severely. The women and children are in a state of terror. The rioters have charge of the place. Some of the workmen took refuge in the manager’s house, one being badly hurt. As there is no force here to protect life, the manager has telegraphed to Sydney asking the authorities there to send constables immediately.162

The telegram was designed to elicit horror, and other news reports repeated claims that the union men had arrived in Lingan as “a half drunken crowd of ruffians.”163

The violence was, in fact, purposeful and coordinated, if not entirely anticipated. Though there was a tradition of vigilantism and direct action among the miners, collective action of this scope had not been seen before on the Sydney coalfield. The gma requested regular troops be brought in, and 100 men of the Prince of Wales’s Own Yorkshire Regiment boarded the steamer Newfoundland in Halifax on 27 March with “arms and ammunition ready prepared for a fight.” The Newfoundland government, however, would not permit the steamer’s planned journey to St. John’s to be prolonged by a stop at Louisbourg to deposit the military force, and Prime Minister Macdonald insisted on the deployment of Canadian militia instead. The British troops were required to unload their gear from the ship and return to barracks. The following day 25 members of the Sydney Volunteers arrived in Lingan under the command of Colonel Crowe Reed.164

The gma was not able to restore order on its terms. That night, at two o’clock, Chief Const. Musgrave arrived in Little Glace Bay from Lingan with seven volunteers and six constables to arrest men in connection with the Lingan riot. “They arrested Joe Currie and brought him down to jail,” fifteen-year-old Allan Joseph McDonald reported to his father, William, who was away in Ottawa at the time for Parliament. Next, Musgrave proceeded to the home of Simon Lott, a miner over 60 years of age and a member of Keystone Lodge. He broke down the door, and, as Allan Joseph described it, “dragged old Simon out.” But, as Allan Joseph continued, “some of the Union Men heard the noise and they went all around the other houses telling [people] what was wrong[.] Then all the men followed Musgrave and the soldiers up to McPherson[’]s and Musgrave hid there.” An angry crowd of about 300 people gathered outside McPherson’s house where Musgrave was sheltered. The crowd, reported Allan Joseph, “would have killed him,” given the opportunity. A warrant for Musgrave’s arrest was obtained, and he was collected and placed in jail. The volunteers and constables departed Little Glace Bay before noon and without Musgrave, who was bailed out of jail the following day by Henry Mitchell.165 The episode was an outright defiance of constituted authority, and it revealed the interlacing of the miners’ perspectives with a broader community solidarity that could be mobilized to enforce collective moral judgements. The outside report of the Montréal Gazette – which claimed that the constable had “escaped to the lock-up … to save himself from the mob” – evaded acknowledgement of the full extent, and deliberate nature, of the popular agency exercised at Little Glace Bay.166 The coal operators perhaps wished not to openly expose the limitations of their power to the outside public.

After refusing to negotiate for over a year, on 17 April, the gma asked to meet with the committee of Coping Stone Lodge. An agreement was reached on 24 April, which was ratified by the cbca.167 The provisions of the agreement were published in the Trades Journal. The manager was to recognize the committee of Coping Stone Lodge and provide work without distinction to those “not convicted of having violated the law.” The manager also promised to do what he could to “put a stop to all further proceedings against any union men.” The agreement included provisions protecting against arbitrary dismissal and the opportunity for miners to return to company houses under old terms.168 The pwa presented the agreement as a victory. The cbca’s secretary, William Purves, prepared a letter denying this claim.169 But local people felt the strike had been won for the miners. “The Lingan strike is ended in favour of the men,” wrote Michael Farrell from Little Glace Bay. “And tuff one it was.”170

VII

Memories of the conflict persisted in Cape Breton’s coal country in various forms. “From Rocky Boston they do come,” reported a protest song of the period, in reference to rural labourers from nearby New Boston, or Rocky Boston, who arrived seasonally to work in the coal mines (see Figure 1). The title of the song, “The Yahie Miners,” is derived from a corruption of the lenited Gaelic word for home, dhachaigh, as in expressions such as Tha mi ‘dol dhachaigh (“I’m going home”). To non-Gaelic ears overhearing such phrases, dhachaigh sounded something like “yahie.”171 Gaels who migrated from rural home communities in the spring for seasonal work at the coal mines, always to return home, were thus labelled Yahies or Yahie Miners:

Early in the month of May

When all ice is gone away,

The Yahies, they come down to work

With their white bags and dirty shirts,

The dirty Yahie miners.

Modelled after “The Blackleg Miners,” which originated from the Northumberland and Durham lockout of 1844, the song deployed “Yahie,” above all, as a metonym for a blackleg or scab, unwelcome in the coal mining village:

They take their picks and they go down

A-digging coal on underground,

For board and lodging can’t be found

For dirty Yahie miners.

There is considerable evidence to suggest that the song was derived from events of the Lingan strike. The central role of Donald Lynk in the strike, and his ongoing efforts to recruit rural labourers as strikebreakers, helps to explain the process of cultural selection that led to the creation of such a song. And we find Mitchell named in it, followed by a plea to join the union:

Into Mitchell’s they do deal,

Nothing there but Injun meal.

Sour molasses will make them squeal,

The dirty Yahie miners.

Join the Union right away,

Don’t wait till after pay,

Join the Union right away,

You dirty Yahie miners.

Sources of intimidation arrayed against the union are subsequently identified. One suspects that the following verse was a reference to John (“Smoker”) McDonald, the Lynk deputy whom we encountered several times at Lingan, or possibly a reference to Lynk’s gun-wielding office clerk, Alex McDonald:

Don’t go near MacDonald’s door,

Else the bully will have you sure;

For he goes ’round from door to door

Converting Yahie miners.

In this context, recourse to physical force is celebrated as a justified – indeed, heroic – act. Thus, the following chorus:

Bonnie boys, Oh won’t you gang,

Bonnie boys, Oh won’t you gang,

Bonnie boys, Oh won’t you gang,

To beat the Yahie miners.

Violence – and the threat of violence – was indeed ubiquitous during the strike, especially as tensions mounted in the weeks before the confrontation at Lingan. Shortly after Lynk’s men were reported to have been menacing people in Little Glace Bay, Allan Joseph McDonald reported to his father that “the union men at Lingan nearly killed two men from East Bay named McEachern the other day” – men who had been hired by Lynk to work on “some houses there.”172

The song ends with confirmation of the miners’ triumph through physical might and intimidation:

The Lorway road it is now clear,

There are no Yahies on the beer,

The reason why they are not here,

They’re frightened of the miners.

This, very likely, was a narrative of the Lingan strike.173

The internecine conflict of the strike, of course, revealed Gaels as both “Yahie” and union miners. But while the violent confrontation at Lingan and its aftermath had created the conditions for the settlement of the strike, it also eroded some elements of the cross-class basis upon which the strike had been fought. For Lithgow, the episode shattered his earlier optimism about class harmony. He wrote, almost apologetically, to Mitchell, “the events at Lingan have opened my eyes to see what many of the men you have to deal with are.” The men, he believed, had “outlawed themselves.”174

Yet even here, popular attitudes on the coalfield attenuated punitive application of law. One of the union men, Thomas Peck, was convicted in the summer for his involvement in the Lingan riot. The judge in Sydney handed him ten months in prison for common assault. The jury was surprised by the length of the sentence, and the pwa protested it. William McDonald, along with clergy and other public figures, petitioned the Minister of Justice for Peck’s release. Even R. H. Brown publicly declared the sentence too harsh, perhaps bending to the public mood.175 Peck was later released, and the Cape Breton subcouncil extended thanks to Father Joseph Chisholm, who had led congregations in many parts of the coal district, for his work in Ottawa lobbying for Peck’s release.176 Not only were the actors in the riot judged with considerable sympathy; local anger was directed toward those who had called for deployment of the militia, and the county refused afterward to pay for its services.177

The gma nevertheless possessed considerable private power and sought to exercise that power to punish perceived disloyalty. Though Ronald McDonald “did much for the Company at the time of the calling out of the Red Coats,” the practice of stopping miners’ pay at his store in Lingan was halted after the strike. This was William McDonald’s brother-in-law; one suspects that this association was the cause for the change. And Dr. Michael McDonald, William’s brother who had provided medical care to Lingan residents during the strike, was informed that the gma would no longer require his services at South Bar and Low Point.178 He remained esteemed in Lingan, nonetheless. A letter to the doctor signed by twenty Lingan residents was published in the Trades Journal the following year: “Your attendance during that d[i]stressing period of the strike deserves especial thanks – when you attended to our wants without any renumeration.”179

The gma’s move to shut down shipping facilities at Lingan by the end of 1883 and to close the mine altogether a couple years later might also be viewed as a strategy to evade the collective judgement of the coal communities. Coal production was shifted to Victoria Mines. And with Lynk at the helm, it gained the reputation as a scab colliery. John Moffatt arrived in Cape Breton in November 1883 from Scotland with his uncle and aunt among a group of “Irish + Scots … brought out to [L]ow [P]oint by Rev. J. Murray.” At Victoria Mines, Moffatt quarrelled with the overman. His efforts with others there to form a pwa lodge failed. As Moffatt recalled, “we were put out of our home … it fired me with indignation against Lynk.” After another confrontation with Lynk, Moffatt found work at Reserve Mines under his mother’s name, indicative of continued efforts to circulate and enforce blacklists on the coalfield.180

Yet Lynk struggled to recruit and keep colliers at Victoria Mines as the demand for labour grew later in the decade. A letter writer from Lingan reported in 1887 that the mine was “worked by a few scabs who cannot show their noses in any other colliery in Cape Breton,” while other collieries were “thronged with miners.”181 By the following year, Lynk had been removed as mine manager, and a pwa lodge (Victoria No. 22) was organized in January; “thank God he is going never, I hope, to have the privilege of using his bad english in giving commands to colliery workers,” read another letter published in the Trades Journal, signed “RETRIBUTION.”182 “The reproach of being a scab colliery has, at length, been removed from Victoria Mines,” crowed the Trades Journal.183

At Sydney Mines, R. H. Brown may have taken some comfort in the bankruptcy of W. H. Moore & Co. in January 1884 and the considerable local business captured by the gma’s company store.184 Yet here, too, the miners replied in kind. The establishment of co-operative stores, “owned and managed by the union men themselves,” emerged as a subject of discussion in Cape Breton during the period of the Lingan strike.185 Before the end of the decade, co-operative stores had spread throughout the south side of the coalfield, in Little Glace Bay, Bridgeport, Cow Bay, and, indeed, Victoria Mines.

VIII

To the extent that it has been considered at all, historians have viewed the Lingan strike as a short-lived rebellion of passing significance.186 This article has presented a different picture. The strike was part of a fundamental reconfiguration of class relations on the Sydney coalfield that accompanied National Policy industrialism. In linking Cape Breton to Montréal and other St. Lawrence coal markets under the National Policy, colliery owners and politicians may have restored activity at the mines, but they also participated in making a political economy that was far from being wholly under their control.187 Patterns of rural migration to the growing mining villages on the south side of Sydney Harbour had reassembled Highland communities at the mines. From the 1860s to the early 1880s, shifting loyalties within these new coal communities expanded support for the miners, including among established political and religious figures. The miners consequently commanded broad local support that seriously rivalled the gma’s authority. The rapid spread of the pwa in Cape Breton with the expansion of the coal trade in the 1880s confirmed this shift.