Labour / Le Travail

Issue 92 (2023)

Note and Document / Note et document

Labour and the Law in Canada, an Essay by Maurice Spector

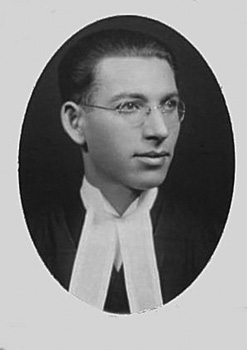

Spector’s Osgoode Hall graduation photograph, 1932, taken by Charles Aylett.

Image from the Archives of the Law Society of Ontario’s Flickr page.

Maurice Spector helped found the Communist Party of Canada (cpc), served as the first Canadian member of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ecci), and, after being ousted from the cpc, became a leading figure among Canadian Trotskyists. Yet, if relatively little has been published about Spector’s life as a leftist, almost nothing is known of his life as a lawyer in Ontario in the 1930s.1 Fortunately, tucked inside Spector’s file at the Law Society of Ontario is his 1932 law school essay “Labour and the Law in Canada.” The essay was written for the inaugural Wallace Nesbitt prize, a stand-alone writing contest, rather than for a course. It earned Spector third place and $25, and it provides a succinct summary of the state of the law at the height of the Depression as seen by one of Canada’s most notable Marxist thinkers.2

Spector’s legal career was interrupted by nearly a decade’s full-time labour in the international communist movement. He was admitted to Osgoode Hall for legal studies in October 1921. At the time, the program consisted of three years of study with a concurrent three years of articling. Finding an articling principal in Toronto was no small feat, especially for a Jewish man with no family connections of note.3 Nonetheless, Spector secured a position with John George O’Donoghue, a labour lawyer and activist whom Spector presumably met in the course of his own early labour organizing efforts.4

Son of Daniel John O’Donoghue, a prominent labour organizer and the first “workingman’s candidate” to be elected in a Canadian provincial legislature, J. G. O’Donoghue represented the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada (Spector specifically refers to some of O’Donoghue’s work in this capacity in his essay) and served as a director for the Moral and Social Reform League.5 He seemed an ideal fit as principal for someone with Spector’s interests, ambitions, and talents. But Spector chose a different path. Five months before he began his articles, Spector attended the founding convention of what would become the cpc. His work for the party – which soon included labour organizing, writing, editing, and even travel to Moscow – soon consumed his every waking moment. He walked away from his legal studies after the first year, although technically he was still in the program.

In 1928, Spector was appointed a member of the ecci in Moscow. Within weeks, however, he was purged from the cpc’s ranks for refusing to denounce Leon Trotsky. Along with Americans James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman, and Martin Abern, Spector became a leader within the Communist League of America, or the American Left Opposition.6 Spector moved back and forth between Toronto and New York, serving as an editor for the Left Opposition’s The Militant and a director of the small but growing organization. He returned to Toronto, established a Left Opposition branch, and resumed his legal studies in the fall of 1929.7 He could not return to his original articling principal, as O’Donoghue had moved to New York City.8 Spector instead picked up his articles with Meyer Rotstein.9

Like Spector, Rotstein was born in 1898 to a Jewish working-class family in what was then the Russian Empire (Spector in Ukraine and Rotstein in Poland). Both arrived in Toronto as young children, and their fathers worked in similar jobs: Rotstein’s a scrap metal dealer and Spector’s a hardware merchant. The two young men began their studies at the University College at the University of Toronto in 1915, where they almost certainly knew each other.10 This was where their biographical similarities ended. Rotstein finished his undergraduate degree without interruption, completed a law degree at Osgoode Hall, and began practising in 1922. He took his first case less than a week later.11 Rotstein was sympathetic to the plight of the working class, but he was hardly a communist. His obituary described him as “active in Progressive Conversative circles.”12 He also advertised his legal services in, among other periodicals, the Toronto-based Il Bollettino, an Italian Canadian newspaper that provided a voice for the Italian community but also a platform for fascists.13 Such advertising was pretty ordinary for the time but quite possibly resulted in some ideological tensions between the conservative-leaning principal and his revolutionary articling student. Spector, however, could hardly afford to be picky. By this time, his reputation as a Marxist and a Trotskyist was public knowledge, closing the door to articling positions to lawyers of conventional politics and even the very few who might hold sympathies to the cpc. He likely had few options.

As for his classroom instruction, Spector must have stood out among his classmates. He was not the oldest – that was William Basil Cross, born in 1896 – but he was five to ten years older than most of his fellow students. Most students had clearly Anglo-Saxon names (like Wilfred Judson, a future justice of the Supreme Court of Canada), but several were also working-class Jews, including Samuel Gotfrid, later a successful commercial lawyer and initial articling principal to future chief justice of the Supreme Court of Ontario, Bora Laskin. Spector’s class included only one woman: Tmima Mamie Littner Cohn.14

Spector was, of course, the only former member of the ecci in Canada, let alone at Osgoode Hall, and he remained politically active throughout his studies. He continued to work with the New York Left Oppositionists and led the small branch in Toronto. This division of Spector’s attention caused problems in both parts of his life. The young and energetic section of the Toronto Left Opposition was growing frustrated with Spector’s attention to his legal studies. A young William Krehm, a second-year student at the University of Toronto, and a slightly older man known only as “Roth,” attacked Spector in the spring of 1932.15 They stated that Spector was responsible for the stifled growth of Canadian Trotskyism owing to his focus on law school, writing in a statement that “the whole activity of the Toronto branch was subordinated to the exigencies of Spector’s legal studies. Group meetings were postponed or not called at all in order to accommodate [him] … there was really no organized group.”16 Unsurprisingly, when the matter was referred to the leadership in New York, they sided with Spector over the young usurpers, but the whole affair was very distracting for Spector.

Spector’s own legal risk of prosecution as a former member of the cpc created another distraction. In the summer of 1931, between Spector’s second and third year of studies, police arrested eight cpc leaders and charged them under section 98 of the Criminal Code. The law prohibited “any association … whose professed purpose … is to bring about any governmental, industrial or economic change within Canada by use of force, violence or physical injury to person or property.”17 The leaders’ conviction in December rendered almost any act relating to the cpc a criminal act. Spector attended the trials and was understandably worried when he heard the Crown prosecutor state that such “former leading members of the party as Jack MacDonald, one-time party secretary, and Maurice Spector, former editor of The Worker [the cpc newspaper],” were potentially liable for prosecution.18

Consequently, while Spector was studying for his third-year examinations, he was also managing a unity crisis within his organization, leading delegations to protest section 98, and quietly working to bring Jack MacDonald into the Left Opposition. Understandably distracted, Spector failed his third-year examination on wills.19 Although his image was included in the 1932 class composite photograph, Spector did not graduate until after his retest in 1933.20

Spector wrote his essay “Labour and the Law in Canada” against this tumultuous backdrop. As the essay shows, Spector was critical of the supposed advances in the legal recognition of trade unions made through legislation during the 1870s and the protections against criminal prosecution afforded by section 590 of the Criminal Code. Spector argued that these protections were very limited and were often nullified either by the injunction or anti-conspiracy laws, especially in the case of industrial, general, and sympathetic strikes. Spector’s comments on the limited nature of trade union protection were at odds with contemporary, mostly positive, treatment of the 1872 Trades Union Act and the 1877 Breaches of Contract Act but have subsequently been supported in full by more recent critical scholarship.21 Spector also expressed much concern that section 98 of the Criminal Code and prohibitions against “seditious words” could be applied to the trade union movement whenever they pursued broad socialist goals. Section 98 was not applied so broadly, and was soon repealed, but this fear was an entirely understandable concern at the time.

Having failed his wills examination, Spector had to spend an additional year as Rotstein’s articling student, after which he began working for Samuel Cohen.22 Cohen, five years older than Spector and Rotstein, had an office on the same floor of the same building as Rotstein – presumably that is how the otherwise unconnected Cohen and Spector met.23 Cohen’s practice was broad but focused mostly on bankruptcy and debt collection. Cohen certainly had a social conscience, later becoming an important advocate for child and family welfare, but there is no obvious connection between Spector’s interests and Cohen’s practice apart from it including some garment manufacturers as clients.24

Most likely, the connection was simply one of opportunity. Spector was more financially prosperous working with Cohen than he had ever been as a full-time political organizer for the cpc. Spector, able to afford his own residence for the first time in his life, left his family’s long-time home on Palmerston Avenue to move into one of his own on Medland Court, north of Toronto’s High Park.25 He might have continued the working relationship had police not arrested Cohen in October 1933 for pocketing $891.13 meant for the creditors of the bankrupted Great Lakes Transport Co.26 The matter did not proceed to trial, but the Law Society suspended Cohen’s licence for six months.27 Spector had to set out on his own.

For the next year, the city directory lists Spector as having his own law office at 465 Bay Street, but there is no such listing in 1935 or any year after that.28 The Canadian Law List, a directory of lawyers, has no entries for Spector whatsoever. By 1937, when Spector decided to move to New York permanently to continue his work with the New York Trotskyists, it made little sense to retain his licence to practice law in Ontario and pay the associated fees. He surrendered his licence on 19 May 1937 and pursued other professional interests.29

By 1944, Spector was working as an editor and as the director of publicity for the Information and Statistic Department within the National Refugee Service, a non-governmental organization assisting refugees from Nazi Germany.30 He did similar work for the American Jewish Committee from 1949 to 1959.31 Spector remained active in revolutionary politics, largely working within the Socialist Party. However, in the late 1950s, when a merger was contemplated between the Socialist Party and Max Shachtman’s Independent Socialist League, Spector told a confidant, “I’m leaving the party. When Max gets in he’s going to go so far to the right that you won’t believe it…. I’m an old Trotskyist. I know the signs. I can’t go on with Max in the party.”32 Spector quietly ended his political career. At about the same time, he became the director of the New York Trade Union Division of the National Committee for Labor Israel and stayed in this position until the time of his death in 1968.33

Spector’s legal career was brief and undramatic by almost any measure, especially when compared with his early career in revolutionary politics. One cannot help but wonder what kind of legal career Spector might have had if he had continued his initial studies under O’Donoghue’s tutelage instead of building the party that ultimately banished him. Spector’s essay “Labour and the Law in Canada” provides probably the only record of his own legal thinking and a rare examination of Canadian labour law by someone with both a conventional legal education and a grounding in Marxism. Additionally, given its prize-winning status and the thoroughness of its citations, it is a useful document as a credible summary of the history and state of Canadian labour law in the early years of the Great Depression. The essay is reproduced in full below with only slight modifications to the typed text to correct minor typographical errors and to reflect the amendments in ink made by Spector himself.

Labour and the Law in Canada

The first attempts of the wage-worker to combine in trade unions34 for the purpose of improving conditions of employment encountered bitter repression by the State. A series of Combination Acts in Great Britain declared a trade union an unlawful society and the strike a crime.35 In France a decree of 1791 prohibits all associations between workers or employers and the Penal Codes of other continental countries likewise deem the right of collective bargaining inconsistent with liberty.36 The hostility to freedom of association (the courts even opposed the formation of joint-stock companies) was an early phase of the capitalist reconstruction of society, involving the form of production, the property relations and the class alignments.37 The industrial and agrarian revolution in the last decades of the eighteenth century release business enterprise from the fetters of feudalism and mercantilism in favor of the freedom of competition and liberty of contract.38 The French Declaration of Rights and the American Declaration of Independence breathe the same spirit of optimistic individualism as Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations.39 The democratic state is conceived as a mass of isolated, free, homogeneous units, each unit a citizen, each citizen an ultimate source of sovereign authority the exercise of which would be fatally impeded by “artificial groups.”40 The end of the law was to secure the absolute and universal natural rights of individuals based upon a social compact, the conception the irreverent Bentham jeered at as “nonsense upon stilts.”41 The common law of England found the new individualism very congenial and for a century and a half the doctrine of laissez-faire in the judicial guise of ‘public policy’ determined the attitude of the Bench towards trade combinations.42

The wage-laborer was in the eyes of the law formally equal with all other citizens. But “necessitous persons are not truly speaking freemen.”43 Sovereignty, whatever the philosophical theories of Rousseau, passed for all practical purposes from the landed interest to the money-power. The democratic device of universal suffrage did not destroy economic classes; it merely ignored them.44 The new freedom brought glittering prizes to the capitalist entrepreneur; to the laborer it brought the factory system, low wages and long hours, slums and employment.45 To speak of liberty of the labor contract under these circumstances was to disregard realities. The individual worker had only a Hobson’s choice.46 The wage-worker was divorced from the ownership of the instruments of production; the only commodity he could bring to market was his labor-power. There is no legal ‘right to work.’ The employer has the right to hire and fire. The laborer lacks reserves and must bear the brunt of the trade depression or cyclical crisis.47 He is relatively immobile, his commodity is perishable and there is always an actual or potential over-supply of laborers. Adam Smith saw plainly that the individual employer was a combination in himself.48 Since the end generally of the period of laissez-faire and the rise of gigantic combinations, trusts, cartels and interlocking directorates which dominate mass production, world trade and finance, the individual, unorganised worker is an even more helpless figure in the determination of his economic fate.49

Trade Unionism is the organised refusal of the wage-worker to submit passively to “inexorable laws” of supply and a demand. It is based on the view that the standard of living is not fixed automatically but can be influenced by the force of combination.50 The penal measures proved ineffective to prevent strikes and lockouts and illegal association and the repeal of the legislation prohibiting combinations for trade purposes took place in England in 1824 and in the majority of European countries in the course of the second half of the nineteenth century.51 There followed a period during which political and economic circumstances, though not without wide zig-zags, enabled the trade unions to secure additional concessions, by the grant, for example under the Trade Union Acts of 1871 and 1906, of particular immunity from liability under the doctrine of conspiracy in both its criminal and civil aspects.52 The trade unions, wrote Frederic Harrison, are essentially clubs not trading companies and as such, the objects at which they aim, the rights which they claim and the liabilities which they incur, are for the most part such as courts of law should neither enforce nor modify nor annul. They should rest entirely on consent.53 But already in 1902 the historians of the trade union movement had occasion to record that “the public opinion of the propertied and professional classes is in fact even more hostile to trade unionism than it was a generation ago … under the influence of this adverse bias the courts of law have for the last ten years been gradually limiting what were supposed to be the legal rights of trade unions.”54 The recent trend has been even more markedly in the direction of the greater governmental regulation and restriction of trade union activities. Few will contend that the Emergency Powers Act55 and Trade Union Act of 187256 are landmarks of a more cordial feeling towards the trade unions in England. In the newer countries, Australasia, the United States and Canada to the merely permissive character of the older legislation regarding strikes and lockouts has been added a coercive element.57 Australia and New Zealand have made compulsory both arbitration through administrative tribunals and compliance with the award. Statutes forbid the boycott, peaceful picketing and even the simple strike. Use of the injunction to enforce compliance with these prohibitions is sanctioned and violation of the statutes made punishable by criminal proceedings.58 The high-water mark in the control, or rather dissolution of the trade unions as they have been historically developed was reached by the Fascist Government in Italy which announced as its policy to break with “laissez-faire liberalism and the socialism of class-warfare.” Independent unions are dissolved. The Fascist union are incorporated in the scheme of state administration and are placed under the supervision of the Minister of Corporations. Strikes are completely prohibited, to be repressed like sedition. Civil and penal sanctions guarantee the execution of collective agreements.59

In setting out below, some restrictive features of the legal status of trade unionism in the Dominion, the present writer proceeds from the conviction that under prevailing conditions of private property, production for profit and the wages system, the workers can best maintain and improve their standards of living by full freedom of association and designation of their own representatives to negotiate the terms of employment without the interference, restraint or coercion of the employers or their agents in such concerned activities of collective bargaining or other mutual aid.60 The right to strike and to picket should be free from the fear of the injunction. The trade union should have full freedom to assist each other by direct industrial action or by moral support in any strike or lock-out.61 Domestic and inter-union affairs should be safe-guarded from the jurisdiction of the courts, in so far as the direct enforcement of agreements is concerned.62 Their funds should have the same protection as other associations against embezzlement. To raise the objection to all this of some lawyers that it is creating a new “benefit of clergy”63 is to share the juridical assumptions of the eighteenth century in a vastly different world and to ignore the real correlation of social forces.

The Right of Combination and the Law of Conspiracy

Historically, two doctrines have been invoked against the right to combine in trade unions, the doctrine of conspiracy and the common-law rule holding as unlawful all contracts or combinations in restraint of trade.

The doctrine of criminal conspiracy appears to have been an example of judicial legislation without legal foundation64 originating in the criminal equity administered in the Star-Chamber.65 The gist of the offence is the conspiracy and not the act done in pursuance thereof. It is committed if persons conspire to commit any unlawful act or any lawful act by unlawful means, the common law adopting this definition when it was held that acts which were neither crimes nor torts were yet indictable as contrary to public policy.66 Originally limited to specific offences confronted with the problem of association, the judges extended the doctrine to combinations of workers. The Combination Law of 1799–1800, passed in fear of French revolutionary influence made combinations to raise wages a statutory crime. Under the doctrine of criminal conspiracy, the mere agreeing together for the purpose of calling a strike to raise wages became an indictable offence. But the attempt during the period of Old Toryism as Dicey terms it, to enforce customary wage rates fixed at the Quarter Sessions long after the craft guilds had lost their power and in the face of rapidly changing conditions was doomed to failure. The unions operated as secret societies. Strikes broke out and leaders were imprisoned but in the end the Combination Laws were repealed67 in 1824–25. From 1825 to 1871 a series of cases give form to the doctrine of conspiracy in restraint of trade and carry it so far as to say that any agreement between two people to compel anyone to do anything he does not like is an indicatable conspiracy independently of statute.68 The Trade Union Act of 187169 provided that the purpose of a union should not, merely because they were in restraint of trade, be regarded as criminal nor should they render void any agreement or trust. But the common law expands, writes Stephens, as the statue law is narrowed, and the doctrine of conspiracy to coerce or injure is so interpreted as to diminish greatly the protection supposed to be afforded by the Act of 1874. Finally the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act of 187570 provided that “an agreement or combination of two or more persons to do or procure to be done any act in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute between employers and worker shall not be indictable as a conspiracy if such act committed by one person would not be punishable as a crime.”

The doctrine of criminal conspiracy was accepted in the early colonies of British North America.71 Nova Scotia passed a Combination Act modelled on an Elizabethan statute as early as 1777 and another in 1816. In 1864 Nova Scotia adopted an act which was practically a replica of the English statute of 1825 establishing the right of collective bargaining but restoring the doctrine of criminal conspiracy. In 1800 Upper Canada formally adopted the criminal law of England as of December 17, 1792. In 1867 the British North America Act by assigning the criminal law to the Dominion and property and civil rights to the provinces rendered trade unions subject to the jurisdiction of both. The arrest of twenty four striking printers in Toronto in the seventies on a charge of conspiracy brought home forcibly that the law in Canada in regards to combinations was the law of England prior to the Act of 1871. In consequence, Parliament in 1872 passed an act72 identical in most respects with the English legislation of the previous year except that it applies only to trade unions registered under it. This act laid down that “the purposes of a trade union shall not, by reason merely that they are in restraint of trade be deemed to be unlawful so as to render any member of such union liable to criminal prosecution for conspiracy or otherwise.” In the same year another act declared73 that certain coercive methods would bring the combination within the conspiracy doctrine. In 1876 part of the English Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act was copied to the effect that any act lawful for an individual would be lawful when done in combination and limiting conspiracy to offences indictable by statute or punishable under the act itself.74 Section 590 of the Criminal Code now reads:

“No prosecution shall be maintainable against any person for conspiracy in refusing to work with or for any employer or workman or for doing any act or causing any act to be done for the purpose of a trade combination unless such act is an offence punishable by statute.”

Thus apparently the doctrine of “common-law conspiracy” has received its quietus in this country too. But unfortunately for the trade unions, the narrow definition of a “trade combination” and the qualifying words in the section as to “offences punishable by statute” still leaves sufficient scope for the operation of the “elastic and indeterminable” law of conspiracy. Commenting on the change from “indictable” to “punishable” in the section, the Hon. Edward Blake had occasion to declare in the House of Commons in 1876 that “all offences punishable by statute, even though of the most trivial character and punishable in the lightest way and by the most summary procedure are once more… drawn into the wide net of conspiracy…”75

Restrictions on the Right to Strike

The legal recognition in section 590 of the right to strike, which is of the essence of freedom of combination is, having regard to the conditions of modern industrial disputes, of a very limited character. Some of the most important incidents of a strike, notably picketing, may be punishable by statute. The strike of workers in public utilities before invoking the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act76 is an indictable offence. A sympathetic strike may become a wholesale violation of statutory prohibitions and in addition, a seditious conspiracy.

In the case of Rex v. Russell77, which grew out of the Winnipeg general strike of May 1919, the defence urged was that the strike was the lawful act of a trade combination under the protection of section 590. It was however held by the Manitoba Court of Appeal that;

“The immunity provided by section 590 of the (Criminal) Code does not extend to a general ‘sympathetic’ strike. A conspiracy to bring about a strike involving no trade dispute between the strikers and their employers is illegal. The law in Canada applying thereto is the same as it was in England before the Trade Dispute Act, 1906, to which there is no similar enactment in Canada.

“It is lawful for workmen to combine in a strike in order to get higher wages, because that would be a combination to regulate or alter the conduct of a master in his employment of his workmen. Persons who aided or encouraged such a strike would not be committing an unlawful act, because they were endeavoring to bring about something that is legal. But suppose there is a strike by the moulders in A’s foundry and in order to assist the strike the employees of a cartage company combine in a refusal to carry goods to or from A’s foundry, or the railway company’s employees combine in refusing to receive or handle A’s goods; neither of these combinations comes within the protection afforded by section 590.”

Sympathetic strikes, writes the Editor of the Law Quarterly Review78 have been the practice for over 50 years and to hold that they are illegal at the present time would constitute a revolution in what has been universally held to be the law. This was said in discussion whether a sympathetic strike came within the definition of section 5 subsec. 3 of the British Trades Disputes Act (1906).79 But in the view of the Department of Justice to hold the sympathetic strike legal would constitute the “revolution.” Following the events of the Winnipeg Strike, the Trades and Labor Congress proposed to the Government to amend section 2 subsec. 38 of the Criminal Code defining ‘trade combination’ by adding the words from the English Act of 1906 that “workmen means all persons employed in any trade or industry whether or not in the employment of the employer directly involved in a trade agreement.” In this Memorandum of the Department of Justice in reply, it was affirmed “as a principal of the common law founded in the right of protection of individuals and of the public that a combination of persons to do an unlawful act, or to do a lawful act by unlawful means, is criminal, and it is moreover actionable civilly, if there be special damage. Compatible with this rule a sympathetic strike cannot practically be worked. This is an inheritance which we have from the common law… The decisions of the English courts in Lyons v Wilkins (1896), I Ch pII, Quinn v Leathem (1901) A.C. 495 and in Giblan v National Amalgamated Laborers’ Union, etc (1903), 2 K.B. 600, make it clear that at common law strikes of this nature are illegal, and assuming that the Criminal Code does not conflict, this is the present position of the law in Canada.”80

If this is so, the trade unions which find the craft form of organisation inadequate in the context with the modern consolidations of Capital and seek to parallel the latter by industrial unions, federations and alliances are rigorously handicapped. In the language of an English law lord81 “a dispute may have arisen for example in a single colliery, of which the subject is so important to the whole industry that either the employees or the workmen may think a general lock-out or a general strike is necessary to gain their point. Few are parties, but all are interested in, the dispute.”

But it is not only at common law that the sympathetic strike would seem to be illegal in Canada; the trade unions resorting to it have become vulnerable to prosecution for illegal conspiracy by statute. The Trades and Labor Congress, whose leadership certainly cannot be taxed with radicalism, has on more than one occasion made representations to the government of the day for the repeal of amendment of section 98 of the Criminal Code as a potential danger to the operations of the trade union movement.82 It will be recalled that legislation in response to this pressure did as a matter of fact pass the House of Commons several times only to fail of adoption by the Senate.83 Section 98 of the Criminal Code (its starting point was an order in council issued under the War Measures Act) reads as follows:

“Any association, organization, society or corporation, whose professed purpose or one of whose purpose is to bring about any governmental, industrial or economic change within Canada by use of force, violence or physical injury, or which teaches advocates, advises or defends the use of force, violence, terrorism or physical injury to person or property, or threats of such injury in order to accomplish such change, or for any other purpose, or which shall by any means prosecute or pursue such purpose or defend, shall be an unlawful association.”

It has been pointed out84 that the words in this section “force” and “terrorism” when used in such neighborly conjunction with the words “industrial or economic change” renders the position of trade unions which exercise their militant functions very precarious. “Force” may in the electric atmosphere engendered by a hotly fought trade dispute, be construed as embracing even forms of moral pressure. This in his charge to the jury in Rex v Russell, Judge Metcalf declared that “sometimes it has a deterring effect upon people’s minds by exposing them to have their motions watched and to encounter black looks.” The same judge, commenting on section 132 of the Criminal Code which defines “seditious words” as “words expressing a seditious intention” and a seditious libel as a “libel expressing a seditious intention,” added further that “sedition is a comprehensive term embracing all those practices whether by word, deed, or writing which are likely to disturb the tranquility of the State, and to lead ignorant persons to endeavor to subvert the government and the law of the Empire.” The combined effect of Sections 98 and 132 would in the circumstances of a sympathetic strike or any serious conflict extending over a considerable area make especially difficult the position of a trade union which in its statement of objects goes beyond the conservative confines of ‘business unionism’ and includes socialist aims such as the “abolition of the wage system” or “workers control of industry.”

Picketing85

The right to strike, if it is to be effectual must carry with it as a corollary the right to organize the unorganized and to persuade them to join with the organized on strike. In England the incident of picketing is given a certain measure of legal protection in section 2(1) of the Trades Disputes Act of 1906 which repealed the clause of the 1875 Act legalizing picketing merely for the purpose of communicating information. The section in the 1906 Act reads:

“It shall be lawful for one or more persons, acting on their own behalf or on behalf of a trade union or of an individual employer or firm in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute, to attend at or near a house or place where a person resides or works or carries on business or happens to be, if they so attend merely for the purpose of peacefully obtaining and communicating information or of peacefully persuading any person to work or abstain from working.”

There is no similar legislation in Canada expressly excluding picketing from the statutory prohibition of “watching and besetting.” In 187686 a proviso taken from the English Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act was incorporated here to the effect that “attending at or near or approaching to such house or other place … in order merely to obtain or communicate information, shall not be deemed a watching or besetting within the meaning of this section.” But in the statutory revision of 1892, this protective clause was omitted and has never been re-enacted. Section 501, in the present law governing the subject of picketing, makes it an indicatable offense for anyone who “wrongfully and without lawful authority, with a view to compel any other person to abstain from doing anything which he has a lawful right to do, or to do anything from which he has a lawful right to abstain, … (f) besets or watches the house or other place where such other person resides or works or carries on business or happens to be.”

The difference in the English and Canadian law has been noted in several of the more important decisions. In Cotter v Osborne87 and section for damages and an injunction, Mathers J, who affirmed on appeal stated that;

“Picketing the plaintiff’s shop and other places where their men were employed for the purpose of persuading men not to work is also unlawful under section 501 of the Criminal Code. Watching and besetting the CPR station for the purpose of intercepting and persuading men imported by the plaintiffs not to work for them is similarly against the law.”

The employer-plaintiff was granted a perpetual injunction and damages. In Vulcan Iron Works v Winnipeg Lodge88 the same judge pointed out that if, in addition, the “watching and besetting amounts to be common law nuisance it is within the prohibition of statute.” Under section 221 a common nuisance is defined as “an unlawful act of omission to discharge a legal duty, which act or omission endangers the lives, health, property or comfort of the public, or by which the public are obstructed in the exercise or enjoyment of any right common to all his Majesty’s subject” and it is an indictable offence.

The most important Canadian case on the head of picketing is Renners v The King89 an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada from a conviction under section 501. The Court found that the acts were wrongful and unlawful if the watching and besetting amounted to a nuisance or a trespass, or if the men who were watching and besetting constituted an unlawful assembly. The English case the Court adopted as settling the law was Lyons v Wilkins.90 There the Court of Appeal had to consider the interpretation of section 7(4) of the Conspiracy and Protection Act (1875) which corresponds with slight variations with section 501 of the Criminal Code. It was held that watching and besetting were wrongful because of violation of the statute and because it was a common law nuisance, that is because the means of compulsion were both a crime and a tort.

As a common law nuisance picketing is subject to be restrained by injunction. In Canada Paper v Brown91 Greenfields J. declared that “our Criminal Code fully recognizes the proprietary right of a man to carry on his business without interference, let or hindrance. Section 501 is a clear recognition of right of a man to carry on his business without interference and further right of freedom of action without surveillance, besetting or watching.” Occasionally there is a vigorous dissent from the increasing resort to the use of the injunction to prevent picketing. In Robins v Adams92, when dissolving an injunction Middleton J. in his judgement says among other things:

“The equitable jurisdiction of a civil court cannot properly be invoked to suppress crime, and the civil courts should not attempt to interfere and forbid by their injunction that which is already forbidden by Parliament itself … the question of trade unionism and the open shop are essentially matters for parliament quite foreign to civil courts …. Government by injunction is a thing abhorrent to the law of England and of this province.”

Nevertheless in the preponderance of cases involving picketing the injunction has issued.93 One must conclude that under the present law, picketing may be treated as a crime by statute, and as the tort of nuisance at common law.

The Doctrine of “Civil Conspiracy”

and Incitement to Breach of Contract

Is there any such tort at all as conspiracy? ‘The law on this subject is in a state of chaotic uncertainty.’94 A series of cases beginning with Temperton v Russell95 widening the offence of incitement to breach of contract96 into the doctrine of ‘civil conspiracy’ made it actionable for any combination ‘to induce third persons not to enter into the employ of, or supply goods to, the plaintiff, though no actual breach of contract occurs’ provided damage has been suffered.97 On top of this came the Taff Vale Judgment98 in which the House of Lords reversing the Court of Appeal, held that a registered trade union could be sued for torts committed on its behalf by its officials and Taff Vale Railway Company was awarded damages against the union though ‘there was no historical authority for such a proposition.’99 The British trade unions received this decision with the greatest alarm and as a result of their political pressure100 the Trade Disputes Act of 1906 was passed making trade unions expressly immune, both as corporations and in the persons of their officials, in respect of any wrongful act committed by or on behalf of the union. It was furthermore enacted that:

“1…. an act done in pursuance of an agreement or combination by two or more persons, shall if done in pursuance or furtherance of a trade dispute, not be actionable unless the act, if done without any such agreement or combination, would be actionable …”

“3. An act done by a person in contemplation or furtherance of a trade dispute shall not be actionable on the ground only that it induces some other person to break a contract of employment or that it is an interference with that trade, business, or employment of some other person, or with the right of some other person to dispose of his capital or his labour as he wills …”

In this way the position of the trade unions in England is more predictable than that of the unions in Canada which are still subject to the doctrine that “for a number of persons to combine together to procure others to break contracts is unlawful, and if such other are induced to break and do break, their contracts, this constitutes an actionable wrong”101 and accordingly damages have been recoverable from trade unions in a number of cases.102 In Hay v Local Union No. 25 Ontario Bricklayers and Masons Union103 however, Sorrell v Smith104 was followed where it was declared that “if the real purpose of the combination is not to injure another, but to forward or defend the trade of those who enter it, then no wrong is committed and no action will lie although damage to another ensues, provided the purpose is not effected by illegal means. And further a threat to effect a purpose which is itself lawful gives no right of action to the person injured thereby.” In the same case Lord Sumner exclaims “How any definite line is to be drawn between acts whose real purpose is to advance the defendant’s interests and acts whose real purpose is to injure the plaintiff in his trade, is a thing which I feel at present beyond my power.” Yet another notable jurist had confessed himself baffled. “I have read these cases” (the Mogul Case, Allen v Flood, and Quinn v Leathem) Scrutton L. J. records in Ware and De Freville v Motor Trade Association (71a), “and find it quite impossible to harmonise them.”

The Doctrine of Restraint of Trade

The doctrine of restraint of trade was first applied to contracts by which A agreed to sell to his competitor B the goodwill of his business, accompanied by a covenant of the vendor to refrain from competition. Erle defined the term “restraint of trade” to mean at common law that “every person has individually and the public also have collectively a right to require that the course of trade shall be kept free from unreasonable obstruction.”105 The doctrine was fastened on the trade unions, though not without marked dissent from judges who insisted that it arose in a school of political economy rather than received legal principles,106 during the period of agitation and struggle of the English working classes for the franchise.107 The case which established that militant trade unionism was against public policy as being in restraint of trade was Hilton v Eckersley108 and the new doctrine was consolidated in Hornsby v Close109 and Farrer v Close.110 In the latter, dishonest officials had embezzled union funds by the trade unions concerned and were refused protection because it was held their main object was in itself illegal as being in restraint of trade. In the modern case of Russell v Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners111 which went to the House of Lords, Russell’s widow brought an action against the union to obtain payment of certain accumulated superannuation benefits. The defence held entitled to prevail was that as an illegal association at common law the union could not be a defendant in a civil action.

In the Ontario case of Polakoff v Winters Garment Co.112 an unincorporated trade union brought an action against a member of the Toronto Cloak Manufacturers’ Association (an incorporated society) to enforce an agreement in writing in the nature of a collective bargain for the purpose of settling disputes between the local manufacturers and the local unions. Raney J. found that the common law as declared in Hilton v Eckersley and Farrer v Close, before it was affected by the imperial legislation of 1869113 was the law in Ontario to-day, that is, the rules and practices of the union were against public policy as being in unreasonable restraint of trade, and likewise the collective bargain in question. As a result the union was an illegal association, and as such incapable of maintaining any civil action in an Ontario Court.

A similar question of trade union status arose in the Manitoba case of Chase v Starr.114 Galt J. there too found himself constrained to follow Russell v Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners, and gave effect to the “shameful defence” that the trade union, whose funds had been embezzled, was an illegal society because its purposes were in unreasonable restraint of trade. He was reversed in the Court of Appeal on the ground that public policy in Manitoba, at least, favored the existence of trade unions, and the Supreme Court of Canada concurred though not necessarily on the same grounds. Mr. Justice Raney in the Polakoff case however decided that by reason of the decision of the Privy Council in Robins v National Trust Co115 that the House of Lords is the Supreme tribunal to settle English law, the colonial court which is bound by English law is bound to follow it or a judgment of the Board. Accordingly the view of public policy taken by the House of Lords was held to prevail.

The unions involved in both cases were unregistered associations. The Dominion Parliament in 1872 enacted the Trade Union Act (now R.S.C. 1927 ch 202) which purports to remove the common law disability of registered trade unions to make contracts. Section 32 provides that the purposes of any trade union shall not by reason merely that they are in restraint of trade, be deemed to be unlawful so as to render void or voidable any agreement or trust. But the authority of the Dominion to deal with what is prima facie that subject of property and civil rights has been called into question116 as trenching on provincial jurisdiction. So far as the Trade Union Act gives protection against criminal prosecution the unions would appear to be better protected by the declarations of the Criminal Code.117 Following the judgements in Hornsby v Close and Farrer v Close the Imperial Parliament passed an act in 1869 recognising the rights of trade unions to hold property and to defend it even though their purposes were in restraint of trade, thus giving a measure of protection against dishonest officials. Recourse of the trade unions in Canada that are under the ban of the common law doctrine of restraint of trade is to the provincial legislatures.

1. Spector has not been subject of a full scholarly biography. The split between Spector and what became “Tim Buck’s party” was first examined in detail by Ian Angus in his Canadian Bolsheviks: The Early Years of the Communist Party of Canada (Montréal: Vanguard, 1981). It is a sympathetic but scholarly and well-substantiated history that offers immensely valuable counterpoints to the cpc’s own versions of its history. See also Bryan D. Palmer, review of Canadian Bolsheviks: The Early Years of the Communist Party of Canada, by Ian Angus, Labour/Le Travail 11 (Spring 1983): 243–245. Bryan Palmer’s article “Maurice Spector, James P. Cannon, and the Origins of Canadian Trotskyism” remains the most extensive scholarly examination of Spector and his movement, and Palmer’s detailed biographies of Cannon add further content and context regarding Canadian Trotskyism. Ian McKay presented a conference paper on Spector in 2003, but this work remains unpublished. See Palmer, “Maurice Spector, James P. Cannon, and the Origins of Canadian Trotskyism,” Labour/Le Travail 56 (Fall 2005): 91–148; Palmer, James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890–1928 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007); Palmer, James P. Cannon and the Emergence of Trotskyism in the United States, 1928–1938 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2021); McKay, “Revolution Deferred: Maurice Spector’s Political Odyssey, 1928–1941,” paper presented at the annual conference of the Canadian Historical Association, Dalhousie University, Halifax, May 2003. The Prometheus Research Library’s sizable collection of Trotskyist documents contains much correspondence by and about Spector; see James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman, Leon Trotsky, and Others, Dog Days: James P. Cannon vs. Max Shachtman in the Communist League of America, 1931–1933, comp. and ed. Prometheus Research Library (New York: Spartacist, 2002). Histories and biographies/autobiographies of Communist Party of Canada (cpc) leaders certainly mention Spector, but he is so caricatured as a villain in these accounts that they cannot be reasonably relied on. The most notable example is Tim Buck, Yours in the Struggle: Reminiscences of Tim Buck (Toronto: New Canada, 1977).

2. The Law Society of Ontario is one of only two bar societies in Canada that maintain detailed files on its licensees, the other being the Law Society of Saskatchewan. These files often provide little more than the most basic information about a lawyer’s career: name, date and place of birth, year of their call to the bar, and the name of their articling principal. Sometimes, however, as is the case with Spector’s essay, the files are rich with ephemera that offer special glimpses into their subjects’ lives and thinking. The author is indebted to the invaluable assistance of Paul Leatherdale, archivist at the Law Society of Ontario.

3. For comparison, see descriptions of contemporaries Joseph Cohen (before) and Bora Laskin (after) as described in Laurel Sefton MacDowell, Renegade Lawyer: The Life of J. L. Cohen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2001), 17–20; Philip Girard, Bora Laskin : Bringing Law to Life (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2005), 60–61. Laskin, a Jewish man from small-town Northern Ontario, faced considerable challenges in securing an articling principal. Spector faced the additional barrier of being a known political dissident, which likely made him less desirable for most principals.

4. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Maurice Spector File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

5. On Daniel John O’Donoghue, see Christina Burr and Gregory S. Kealey, “Daniel John O’Donoghue,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto: University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1994), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_donoghue_daniel_john_13E.html. On John George, see “John George O’Donoghue,” in The Canadian Men and Women of the Time (Toronto: William Briggs, 1912), 863.

6. Palmer, Cannon and the Emergence of Trotskyism; Palmer, “Maurice Spector”; Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks.

7. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Maurice Spector File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

8. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, John George O’Donoghue File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

9. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Maurice Spector File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

10. University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services, card catalogue entries for Maurice Spector and Meyer Rotstein; The Toronto Jewish City and Information Directory, 1925 (Hamilton, ON, 1925); 1931 Toronto Jewish Directory (Toronto: International Advertising Agency, 1931).

11. “Unique Claim Will Be a Test of Divorce Law,” Toronto Daily Star, 1 November 1922.

12. “Obituary: Meyer Rotstein, Honor Winner at University Practiced Law,” Globe and Mail, 6 April 1963.

13. Angelo Principe, The Darkest Side of the Fascist Years: The Italian-Canadian Press, 1920–1942 (Toronto: Guernica, 1999), 85–100, 237.

14. Composite photograph of the 1932 graduating class and related biographical files, Law Society of Ontario Archives; Girard, Bora Laskin, 60–61.

15. Palmer, “Maurice Spector,” 134–135.

16. “Majority Grouping of the Toronto Branch responding to the statement of the National Committee of the Communist League of America (Opposition) on the Toronto Branch, signed by William Krehm and All Members of the Majority,” William Krehm papers, in the personal collection of the author. The document, which is undated, was presumably written in the spring of 1932. See also Palmer, “Maurice Spector,” 134.

17. Police initially arrested nine people, releasing one soon afterward. For detailed analyses of section 98, see Dennis Molinaro, An Exceptional Law: Section 98 and the Emergency State, 1919–1936 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2017); Molinaro, “Section 98: The Trial of Rex v. Buck et al and the ‘State of Exception’ in Canada, 1919–36,” in Barry Wright, Eric Tucker, and Susan Binnie, eds., Canadian State Trials, vol. 4, Security, Dissent, and the Limits of Toleration in War and Peace, 1914–39 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2015).

18. Quoted in Maurice Spector, “The Defendants before the Docks in Canada,” The Militant, 5 December 1931.

19. Law Society of Ontario, Legal Education Committee Minutes, 20 October 1932, Maurice Spector File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

20. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Maurice Spector File; composite photograph of 1932 graduating class, both in Law Society of Ontario Archives.

21. Eric Tucker, “‘That Indefinite Area of Toleration’: Criminal Conspiracy and Trade Unions in Ontario, 1837–77,” Labour/Le Travail 27 (Spring 1991): 15–54; Paul Craven, “‘The Modern Spirit of the Law’: Blake, Mowat, and the Breaches of Contract Act, 1877,” in G. Blaine Baker and Jim Phillips, eds., Essays in the History of Canadian Law: In Honour of R. C. B. Risk (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1999), 123–124; Craven, “Workers’ Conspiracies in Toronto, 1854–1877,” Labour/Le Travail 14 (1984): 49–72.

22. The Toronto Might Directory lists Spector as a “student at law” to Cohen in 1933 and 1934, despite Spector being licensed as of October 1933. Might Directory (Toronto, 1933), 298, 1381; Might Directory (Toronto, 1934), 313, 1443.

23. Might Directory (Toronto, 1932), 1345, 1464; Might Directory (1933), 298, 1268, 1381.

24. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Samuel Cohen File, Law Society of Ontario Archives; “Companies Act,” Toronto Daily Star, 15 April 1933; “Practiced Law in Toronto for 36 Years,” Globe and Mail, 31 May 1954.

25. William Krehm, interview by Tom Reid, 28 August 1995; Might Directory (1933), 1381.

26. “Barrister Is Arrested, Charged with Theft,” Globe, 19 October 1933; “Barrister Is Remanded on Charge of Theft,” Globe, 20 October 1933.

27. “Osgoode Hall News,” Globe, 17 March 1934.

28. Might Directory (Toronto, 1935), 1197.

29. Ontario Bar Biographical Research Project, Maurice Spector File, Law Society of Ontario Archives.

30. National Refugee Service Records (rg248), series VI, Information and Statistic Department, 1934–1950, yivo Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

31. Alphabetical Files (rg347.17.12), box 149, folder 5, Maurice Spector, 1949–1959, Records of the American Jewish Committee, yivo Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

32. Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer…: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1987), 73.

33. George Novack, “Maurice Spector, a Founder of Trotskyist Movement, Dies,” The Militant, 16 August 1968; “Once Expelled by Reds Here Maurice Spector, 70, Dies,” Toronto Star, 13 August 1968; Ross Dowson, “Maurice Spector 1898–1968,” Workers Vanguard, 26 August 1968.

34. The term “trade union” is used throughout this essay in its ordinary meaning as applying only to combinations of wage-workers.

35. 39 Geo. III (1799) c. 81; 39 Geo. III (1800) c. 106.

36. The Decree Upon the Organisation of trades and Professions (June 14, 1791). Sections 414 and 415 of French Penal Code. Prussian Industrial Code of 1845.

37. Ogg, Economic Development of Modern Europe.

38. Reform of Poor Law in 1834; Usury Laws repealed in 1854; Limited liability principle given legal recognition in 1855.

39. [Empty]

40. Beard, Economic Basis of Politics; Fisher, Bonapartism, p. 17.

41. Pound, “End of Law,” 27 Harvard Law Review, p. 623.

42. Dicey, Law and Opinion in England, App., Note I, on Freedom of Association: see article “Economic Theories in English Cases Law,” 47 L.Q.R. 195: Winfield, “Public Policy in the English Common Law,” 42 Harvard Law Review, p. 92.

43. Northington L.C. in Vernon v Bethell (1761) 2 Eden 113.

44. Beard, Economic Basis of Politics.

45. Bland, Brown and Tawney, English Economic History (1920), pp. 500–521.

46. Frankfurter and Greene, “Power over Labor Injunction,” 31 Columbia Law Review 389.

47. Taussig, Principles of Economics (1918) Vol. 2, pp. 263–264.

48. Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations.

49. “It is Plain … that free competition means combination and that the organization of the world, now going on so fast, means an ever increasing might and scope of combine.”

50. Webb S., Industrial Democracy (1917), p. 558.

51. 5 Geo IV, c. 95 (1824).

52. Webb, History of Trade Unionism.

53. At the Royal Commission on Trade Unions 1869. Minority Report.

54. Webb, Industrial Democracy.

55. 10 & 11 Geo V c. 55.

56. 17 & 18 Geo V c. 22.

57. [Empty]

58. Government Intervention in Labour Disputes – Supplement to Labour Gazette, March 1925, Dept. of Labour, Ottawa.

59. “Freedom of Association,” Vol. 4–5, p. 84, Published by International Labour Office, 1927, Geneva.

60. Compare the terms of the Shipstead Bill S 2497 introduced in US Senate Dec 1929 section 2, as reproduced in 31 Columbia Law Review 389.

61. Cp. Resolution passed by British Trades Congress 1924 T.U.C. Ann. Report 1924, pp. 487, 338.

62. Cp Trade Union Act 1871; 34 & 35 Vict., c. 31 (Imp).

63. See Memorandum of Department of Justice, April 29, 1921, quoted 1921 Trades and Labour Congress Proceedings 25.

64. Sayre F.B., “Criminal Conspiracy,” 35 Harvard Law Review 393.

65. Holdsworth, History of English Law, Vol. VIII, p. 380.

66. ibid. p. 380.

67. Webb, History, p. 77.

68. Stephens, History of the Criminal Law in England, Vol III, p. 226.

69. 1871; 34 & 35 Vict., c. 31.

70. 1875 38 & 39 Vict., c. 86.

71. Bryce M. Stewart, Canadian Labour Laws and the Treaty, p. 116.

72. Now R.S.C. 1927 c. 202.

73. “an Act to amend the criminal law relating to violence threats and molestation” (1872, c. 31).

74. 1876 c. 37.

75. House of Commons Debates 1876.

76. 1907, c. 20, 51.

77. 1920, 51 DLR 33.

78. A.L. Goodhart, Essays in Jurisprudence and the Common Law, p. 234.

79. 6 Edw VII c. 47.

80. supra (30)

81. Conway v Wade (1909) A C 506 at 512.

82. Proceedings of the Trades and Labour Congress 1921.

83. The Honorable Ernest Lapointe, Minister of Justice in introducing his bill for the amendment of the Criminal Code June 1926, “These two sections which we intend to repeal (then 97A and 97B) were added to the Criminal Code in 1919… Since that time labour in general but especially organized labour, has continually and strongly complained about these two sections…”

84. Mr. J.G. O’Donoghue K.C. who was legal adviser of the Trades and Labor Congress for many years submitted a brief statement on this head to the Congress in 1920. See proceedings for that year.

85. [Indecipherable ink amendment]

86. 1876 (Can) c. 37.

87. (1909) 18 Man L R 471.

88. (1911) 21 Man L R 473.

89. (1926) 31 DLR 669, 46 CCC 14.

90. (1899) 1Ch Div 255.

91. (1922) 66 DLR 287.

92. 1924 56 OLR 217.

93. Salmond on Torts, 7th ed., p. 603 note (b).

94. 1893 I.Q.B. 216.

95. Lunley v Gye 2 E & B 216. “The new retort of persuasion to break a contract created by Lunley v Gye” Holdsworth, History, Vol. VIII, p. 380.

96. Quinn v Leathem (1901), A.C. 426.

97. Taff Vale Railway Company v Amalgamated Society of Railway (1901), A.C. 426.

98. Jenks, E., Short History of English Law, 336.

99. Labour Representation Committee (now Labour Party) obtained twenty-nine seats at the General Election, which was dramatic gain.

100. per Perdue J.A. in Cotter v Osborne 18 Man LR 491.

101. 1929 OLR 418.

102. 1925 AC 700.

103. 1921 3 K B at 66.

104. Krug Furniture Co. v Berlin Union of Amalgamated (1903) 5 OLR 463. Brauch v Roth 10 OLR 284.

105. Erle, Sir William, On the Law Relating to Trade Unions, p. 6.

106. Mr. Justice Hannen in Farrer v Close 10 B and S 553 (1869).

107. Mr. Justice Raney in Polakoff v Winter Garment Co., “it during the period of struggle and social unrest that the doctrine of restraint of trade was fastened upon the trade unions.”

108. (1855) 6 E & B 47.

109. (167) L R 2 Q B 153.

110. (1869) L R 4 Q B 602.

111. 1912 A C 421.

112. 33 O W N 385; 6 Canadian Bar Review 222.

113. 32 & 33 Vict. ch 6.

114. (1923) 33 Man R 26; 1924 S C R 495.

115. 1927 A C 515 at 519.

116. vide Mr. Justice Duff’s judgment in 1924 S C R 495.

117. Sections 496 and 497.

How to cite:

Tyler Wentzell, “Labour and the Law in Canada, an Essay by Maurice Spector,” Labour/Le Travail 92 (Fall 2023): 281–307, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2023v92.0011.

Copyright © 2023 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2023.