Labour / Le Travail

Issue 92 (2023)

Presentation / Présentation

Left Americana and the Ludlow Monument

“One way or another, this darkness has got to give.”

—The Grateful Dead, “New Speedway Boogie,” 1970

Near the end of Thomas Pynchon’s sprawling Gilded Age epic, Against the Day, there is a chapter that serves as a semi-fictionalized account of the Ludlow Massacre, the central event of the Colorado Coalfield War of 1913–14.1 Though part of a typically Pynchonian narrative that is wacky, tragi-comic, and undeniably Americana, his account of the massacre largely hews to historical truths. No exaggerations need to be made about either the steely resolve of the United Mine Workers of America (umwa) and their families or the maniacal brutality of the Rockefeller-backed company thugs and state militia. As usual, Pynchon is at his most profound when real history is revealed to be as hyperbolic as his most fantastical prose.2

The Ludlow Massacre, as readers may already know, refers to a deadly attack on the umwa’s encampment in Ludlow, Colorado, in 1914. The miners had been engaged in a months-long strike at John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Colorado Fuel and Iron Company for union recognition, an eight-hour day, better pay, and safer working conditions. Indeed, as Thomas Andrews notes in his history of the Coal War, the Ludlow miners faced high death rates on the job – over twice that of the national average for miners elsewhere in the country.3

On 20 April 1914, mercenaries from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, hired by Rockefeller, worked with soldiers from the Colorado state militia to sneak into the miners’ encampment and light their tents ablaze, causing confusion and panic within. Perched in their armoured cars outfitted with machine guns (deemed “Death Specials”), the company men and militia then opened fire on the camp, the hail of bullets preventing residents from leaving and forcing women and children to retreat to cellars beneath the tents. The attack killed not only miners but also their wives and children, who died from burns or asphyxiation in the cellars. Also murdered was Louis Tikas, a Greek immigrant who was the umwa’s leading organizer at Ludlow; his body was later found riddled with bullets. Current estimates suggest that at least twenty died from the fires and shooting, though some contemporary accounts reported dozens more. Julia May Courtney – writing for Emma Goldman’s anarchist journal, Mother Earth – reported a much deadlier result, stating that “fifty-five women and children perished in the fire of the Ludlow tent colony.”4 The death count, furthermore, does not account for other injuries suffered by the strikers and their families in either the initial attack or subsequent looting by the militia.

This cowardly attack provoked a response from the surviving miners, who armed themselves and skirmished with the company men, state militia, and other strikebreakers in the following days – dubbed the “Ten Day War” – until President Woodrow Wilson sent in the military to disarm both sides and end the conflict. After the violence subsided, the miners continued the strike, but they had exhausted their funds by December 1914 and had to return to work. The strike was defeated, but the umwa’s resolve in the face of brutal repression inspired workers in later labour wars, like the Battle of Blair Mountain, and continues to remind us of the sacrifices that ordinary men and women made in the early 20th century to gain many of the rights that we now take for granted (but that have been threatened in recent years), such as the right to unionize and the eight-hour working day. The Ludlow miners found sympathy for their cause across the country and were subsequently memorialized in literature, such as Upton Sinclair’s King Coal, and inspired folk songs like Woody Guthrie’s “Ludlow Massacre.”

A Visit to Ludlow

The umwa bought the site of the massacre in 1916 and, in 1918, built a granite monument to honour the victims of the company violence. The federal government deemed the memorial a National Historic Landmark in 2009, and it remains a pilgrimage of sorts for union members and labour historians throughout North America. It just so happened that I was digesting Pynchon’s work while planning a trip to the American Southwest with my fiancée, Crystal. Reading Against the Day, I was struck by the cruelty of this particularly dark moment of labour history that I admittedly, as a Canadian, had been only vaguely familiar with. Yet, as often happens when reading about such events – Canadian history is, of course, marred by similar instances of violence against strikers – I was also inspired by those brave men and women who had the courage to engage in life-and-death struggles with their own government and one of the richest men in the world just to assert their democratic rights and to eke out a little more dignity on the job despite the rather hopeless odds against them. Crystal and I had already planned to drive from Denver to Santa Fe as part of our trip, and the Ludlow memorial turned out to be conveniently located just off I-25, before the mountain pass from Colorado to New Mexico. We planned to stop to pay our respects and see the hallowed grounds for ourselves.

Monument to the Ludlow miners.

Photo by Crystal Kelly. Courtesy of Crystal Kelly and Sean Antaya.

On the day of our drive to Santa Fe, after a morning hike in Colorado Springs at the Garden of the Gods, we arrived at the memorial site in the late afternoon. The memorial itself is not very far from the highway, but when we arrived, we felt completely alone out in those vast prairies. The site was silent except for the odd gust of wind that stirred up tumbleweeds or the occasional crow that cawed in the distance. The overcast skies added to the gloomy and sombre ambience of a place that had seen so much bloodshed and tragedy.

I thought about how isolated the miners must have felt – many of them far from their countries of origin and attacked by their country of residence. True, they had their union comrades and a strong sense of solidarity, yet even this too must have been fraught with suspicion, for informants and provocateurs lurked in their midst, always threatening the cohesion of this hard-scrabble community.

Parking lot in the prairies and overcast skies overhead.

Photo by Crystal Kelly. Courtesy of Crystal Kelly and Sean Antaya.

Minecart on display near the pavilion.

Photo by Crystal Kelly. Courtesy of Crystal Kelly and Sean Antaya.

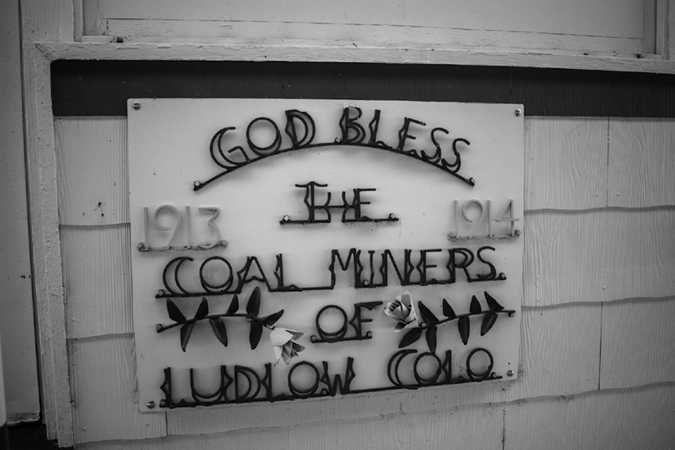

Placard with metalwork in the pavilion.

Photo by Crystal Kelly. Courtesy of Crystal Kelly and Sean Antaya.

Closer to the monument itself, the feeling was more comforting. Previous visitors had left union stickers on a couple of the fence posts, and I regretted that I had not thought to bring a sticker from my own union (the Canadian Union of Public Employees) to leave a record of solidarity from the Great White North. Coins, trinkets, and other tokens of good fortune lined the feet of the monument, and a Bible had been left on a picnic table under the pavilion, perhaps left over from a Labor Day celebration or memorial vigil.

After spending some time reading the historical plaques and taking pictures, we felt the wind change. The eeriness of the site intensified, and we began to wonder if we had perhaps overstayed our welcome with the spirits of the ill-fated miners. And so, we stuck a couple of dollars in the donation box, headed back to the car, and made for the highway.

Prairie Fire

Later in our trip, we began our drive back to Denver, this time taking a path that would send us through the hippie-cowboy town of Taos, New Mexico, the current residence of many of the Easy Rider types who founded communes in the 1960s and ’70s but now run arts and crafts shops near the town plaza or give fly-fishing tours to slack-jawed tourists like myself.5 Scanning the radio while driving on a beautiful canyon road along the Rio Grande, I stumbled on a public radio station playing part of an old documentary on the Industrial Workers of the World (iww) General Strike of 1917, organized by miners and lumberjacks across Washington, Idaho, Montana, Arizona, and Colorado.6 As we drove through the sublime landscape, we listened to old Wobblies recount their fights against company goons and sing their union hymns with banjo accompaniment, and I was again reminded that despite the darkness of the politics of our own times, there remains a trove of inspiration in America for those who seek a better, more humane world. Maybe it was just the altitude affecting a central Canadian more acclimatized to sea-level oxygen intake, but for a moment I got misty-eyed as my mind conjured images of a Southwest peoples’ history: gunslinging coal miners, desert communards, Native American guerilla fighters, outlaw country singers, and gonzo sheriff campaigns.7 All these appeared to me as part of a singular tradition of an America by and for the rabble – the America that is not but could be. On a trip that included hiking across Colorado mountain vistas with friendly Minnesotan Bernie Sanders supporters, horseback riding with Comanche cowboys, and grooving with Grateful Dead cover bands, it was another serendipitous moment of “Left Americana” that this Canuck will not soon forget.8

As the cultural presence of the early 20th-century labour movement fades from view, it is partially in memorial spaces like the Ludlow Monument – many of them similarly tucked away on the side of some forgotten highway detour – that help keep alive the fire of this other America, smouldering though it may be.9 But from time to time, long-dormant embers manage to produce sparks. And, as many ’60s radicals once knew, “even a single spark can start a prairie fire.”10

1. Thomas Pynchon, Against the Day (New York: Penguin, 2006), 1000–1017. Much of this fictionalized book recounts the history of class struggle in Colorado, with anarchists and union organizers pitted against robber barons and their hired goon squads.

2. For relatively recent scholarly literature on the Ludlow Massacre and the Colorado Coalfield War, see Scott Martelle, Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008); Thomas Andrews, Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

3. Andrews, Killing for Coal, 147.

4. Julia May Courtney, “Remember Ludlow!,” Mother Earth, May 1914.

5. For a first-hand account of the New Mexican hippie communes, see Iris Keltz, Scrapbook of a Taos Hippie: Tribal Tales from the Heart of a Cultural Revolution (El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press, 2000). Taylor Streit, a participant in one of these communes, later became a successful fly-fishing guide and now owns Taos Fly Shop.

6. The documentary clips we heard were likely from The Wobblies, directed by Deborah Schaffer and Stewart Bird (1979). For a classic history of the iww, see Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969).

7. The phrase “gonzo sheriff campaigns” refers to Hunter S. Thompson’s 1970 campaign for sheriff of Aspen, which has long fascinated me. See Thompson, “Freak Power in the Rockies,” in The Great Shark Hunt (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979), 151–175.

8. I borrow the term “Left Americana” from Paul Leblanc. See Leblanc, Left Americana: The Radical Heart of American History (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017).

9. For more on the politics of memory and class struggle, see Adam King, “Superstack Nostalgia: Miners and Industrial Heritage in Sudbury, Ontario,” Labour/Le Travail 91 (Spring 2023): 201–225; Peter McInnis, “Curated Decay: Residual Industrialization at the Nova Scotia Museum of Industry,” Labour/Le Travail 91 (Spring 2023): 169–199.

10. Mao Tse-Tung, “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire,” in Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1965), 117–128.

How to cite:

Sean Antaya, “Left Americana and the Ludlow Monument,” Labour/Le Travail, 92 (Fall 2023), 309–314, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2023v92.0012.

Copyright © 2023 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2023.